Will childcare subsidies increase the labour supply of mothers in Ireland?

Submitted: November 2023

Abstract

We study the effect of the largest childcare subsidy scheme in Ireland, a country where, historically, mothers provided childcare and did not participate on the labour market. In 2019, the cost of full-time centre-based childcare was among the most expensive in the OECD. At the end of 2019, a means-tested childcare subsidy was introduced to improve childcare affordability, but nothing is known of the maternal labour supply effects. We model the joint decision of labour supply and childcare for lone and coupled mothers of children under six. Mothers are likely to respond to the introduction of childcare subsidies in 2019 by switching from informal childcare to formal childcare (12 percentage points), and by slightly increasing their participation in the labour market (0.5 percentage points). We simulate that recent (2023) reforms of the National Childcare Scheme, which increase the generosity and the scope of the subsidy, will increase mothers' participation by one further percentage point, but also substantially decrease the demand for informal childcare. Extending childcare subsidies to informal care (such as childminders and nannies) would decrease the demand for formal childcare and further increase maternal labour supply.

1 INTRODUCTION

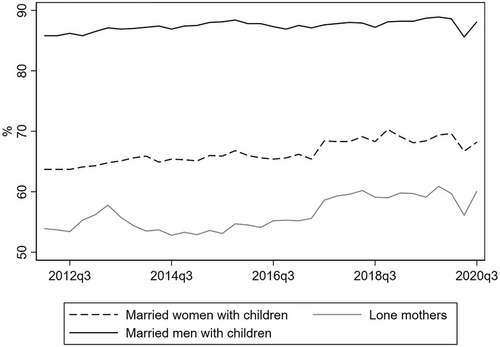

During the 1970s, female labour market participation in Ireland was estimated to be around 7–20 per cent (Fahey, 1990), with women typically acting as primary childcare providers in the home rather than engaging in market work. This resulted in limited formal childcare options until the 1990s (Flood and Hardy, 2013), when female labour market participation started to increase. In recent years, the maternal participation rate has been close to 70 per cent (see Figure 1), but parents in Ireland face some of the highest childcare costs in the OECD (OECD, 2007, 2015, 2020, 2021a).1

Childcare in Ireland can broadly be classified in three categories. Formal paid childcare is provided in a centre-based setting such as a creche or after-school facility. Informal paid childcare is carried out in a home setting. Childminders, who make up four-fifths of this sector (Doorley, Tuda and Duggan, 2023a), carry out childcare in their own homes while nannies care for children in the children's home. Finally, unpaid childcare can be carried out by parents or other relatives.

In this paper, we study the introduction of the largest childcare subsidy scheme in Ireland to date – the National Childcare Scheme (NCS) – and estimate its effects on maternal labour supply and childcare choice. The NCS, which was fully rolled out in 2019, awards universal and means-tested childcare subsidies to families using formal (but not informal) childcare, replacing all previously available childcare subsidies.

We estimate a decision model for labour supply and the choice of formal and informal childcare in Ireland, as in Kornstad and Thoresen (2007), using pre-subsidy data. Using the result of this model, we predict the effects of the introduction of the subsidy on labour supply, including subsequent reforms to the subsidy up to the end of 2023 and proposed reforms for the future.

The advantages of a structural model over reduced-form estimates of how decision-makers respond to tax–benefit policy changes, in this set-up, are: (i) the ability to carry out ex ante analysis of reforms that have not yet been implemented or for which we do not yet have data; and (ii) the ability to generalise the results to alternative policy reforms. The structural approach is necessary for this analysis as the NCS was fully rolled out only at the end of 2019. As childcare facilities were shut down for much of 2020 and 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, any reduced-form estimate of the effect of the NCS using a pre- and post-design is contaminated by this supply-side shock.

We focus on the subsample of mothers (married or cohabiting, and lone parents) with at least one child who is not yet in school, as these are likely to be most affected by childcare subsidies. They may also be more responsive to financial incentives to work as national and international studies show that the gender work and earnings gap opens up straight after parenthood (Albrecht et al., 2018; Kleven, Landais and Søgaard, 2019; Doris, O'Neill and Sweetman, 2022). This means that our results are not readily generalisable to the entire population of mothers and/or parents but, as mothers of young children are the population of most interest when we consider the labour supply effect of childcare subsidies, this focus is natural.

We use the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) tax–benefit model, SWITCH, linked to European Union's Statistics of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) data for 2019, and a discrete choice labour supply model, which accounts for childcare choices and cost – formal and informal. By using 2019 survey data (collected before the full roll-out of the NCS), linked to a microsimulation model, we model labour supply and childcare choices in a pre-pandemic and pre-NCS setting. The results of our simulation suggest how the introduction and expansion of childcare subsidies in Ireland is likely to increase mothers' labour supply in the medium term, abstracting from the effects of the pandemic on both labour supply and childcare provision and choice.

We find that mothers of young children in Ireland are likely to respond to the introduction of formal childcare subsidies through the NCS by (i) switching from informal childcare to formal childcare and (ii) joining the labour market. We estimate that the introduction of the NCS led to a small change in the participation rate of mothers of young children, by percentage points (pp), and an increase in their usage of formal childcare, of 12 pp. Subsequent reforms to the NCS, which came into effect in early 2023 and increased its coverage and generosity, are likely to increase the proportion of mothers of young children working full-time by a further 1 pp and significantly decrease the demand for informal childcare (which is not subsidised). We estimate that, compared with the 2023 parameters of the NCS, extending the subsidy to providers of informal childcare would further increase the labour supply of mothers by 0.5 pp on the extensive (participation) margin, while restoring demand for non-centre-based care.

Previous literature for the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada has found a significant negative effect of childcare costs on female labour supply, and a weak and often insignificant effect of childcare costs on male labour supply (Blau and Robins, 1988; Powell, 1988; Ribar, 1995; Blau and Hagy, 1998; Blundell et al., 2000; Michalopoulos and Robins, 2002; Viitanen, 2005; Brewer et al., 2006, 2016; Francesconi and van der Klaauw, 2007). As emphasised by Del Boca (2015), the largest childcare-price elasticities of labour supply have been found in countries where childcare is or has been provided predominantly by the private sector, such as is the case in Ireland, and subsidisation is low. The estimated effect of childcare costs on labour supply in studies focusing on European countries, which typically have a higher provision of affordable public childcare, has been considerably smaller (Choné, Le Blanc and Robert-Bobée, 2003; Wrohlich, 2004; Kornstad and Thoresen, 2007; Thoresen and Vatto, 2019; Narazani et al., 2022). Childcare characteristics, such as availability and quality, have been found to have a relatively more important effect on labour supply in these countries, and European studies have tended to feature a greater focus on these characteristics.

This research adds to the literature on the effect of childcare costs on labour supply using the case study of Ireland: a country that combines a strong tradition of mothers staying home to care for children, very high childcare costs and historically limited subsidisation of these by the state.

2 THE INSTITUTIONAL SETTING

2.1 Historical background of female labour supply and childcare in Ireland

Formal childcare ‘did not really exist in Ireland (apart from some exceptions) until the 1980s and 1990s […] childcare was usually provided by family members or childminders located in the community and known to the family’ (Flood and Hardy, 2013). The non-existence of formal childcare until relatively recently is explained by the fact that, by and large, mothers in Ireland did not work outside the home: female labour force participation in 1971 was estimated at around 20 per cent (Fahey, 1990).2 There was accordingly little need for childcare services, and what need existed seems to have been serviced by informal care provided by relatives and friends.3

The 1980s saw the beginning of a large growth in the female participation rate, rising from around 30 per cent in 1981 to nearly 50 per cent in 1996 (Fahey, 1990; Bercholz and Fitzgerald, 2016). With more mothers entering the labour force, the issue of childcare became increasingly prominent, which prompted government intervention in the sector.4 This intervention has proceeded in roughly two stages. In the first stage, the government began to regulate the provision of childcare to ensure a minimal standard of adequacy without directly influencing the cost of provision; in the latter stage, the government has begun to more directly influence provision through the social welfare system.

Figure 1 plots the participation rates of men and women with children, distinguishing between married men and women, and lone mothers since 2012. The female participation rate has been steadily rising and, in 2019, the year that the NCS was introduced, was around 70 per cent for married mothers and 60 per cent for lone mothers. Both participation rates were still well below the participation rate of 89 per cent of married men with children.

At the close of the millennium, estimates of the use of paid childcare were still comparatively low by modern standards: 75 per cent of children aged 0 to 2 were cared for by parents in their own home, and the usage of paid childcare services by parents was 38 per cent for parents with children aged 0 to 4 and 18 per cent for parents with children aged 5 to 9 (Williams and Collins, 1998). Contemporary research evidenced both unmet need and inequality of access.

Accordingly, government intervention in the childcare sector from the end of the 1990s began to involve a more than purely regulatory aspect. From 2000 to 2021, five or six different policies providing childcare support were effective at some point: new enrolment in these schemes began phasing out from 2017, when the comprehensive NCS, which is the focus of this paper, was announced.5

The legacy policies of this period were mostly targeted support to ease childcare costs for disadvantaged families as opposed to universal benefits. In 2016, the last year before the announcement that the schemes were to begin winding up, these programmes combined were estimated to affect around 32,000 children, fewer than 10 per cent of pre-school-age children in Ireland (Callan, van Soest and Walsh, 2009; Central Statistics Office, 2017). During the period after 2010, the government replaced all previous schemes with two new childcare policies, which are still in effect: the Early Childhood Care and Education programme (ECCE) and the NCS.

The ECCE constitutes the first universal and free provision of early childhood education in the history of the State. Although its provisions have changed slightly over the years, the programme currently provides three hours per day of free pre-school for qualifying children during the school year. Children are eligible from September of the year that they turn 3 and cease to be eligible if they will turn five and a half during the following school year. Formal schooling typically begins at age 5 in Ireland, although some children start at age 4 and others do not start school until age 6. ECCE providers are paid directly by the government under the ECCE and in return provide their services for free to qualifying children. The impact of the ECCE on maternal labour supply has been investigated by Keane and Logue (2018), who exploit the age thresholds for eligibility to employ a regression discontinuity design. They find no statistically significant effect of the policy on maternal labour supply, which is explained by the observation that three hours a day during the week is simply not enough time for most women to significantly increase their labour supply, particularly at the extensive margin.

2.2 National childcare scheme and subsequent reforms

The NCS, which is the subject of this research, was announced in 2017 (initially as the Affordable Childcare Scheme). During 2017, a universal subsidy of €0.50 per hour of formal childcare was rolled out and, at the end of 2019, an income-assessed subsidy was also introduced. The NCS replaced all the existing schemes, although there is a transition period during which parents could make the switch to the NCS. Children who avail of the ECCE can also avail of the NCS for hours of formal childcare used outside of the pre-school day and/or term. It was envisaged that the NCS would address the high cost of childcare in Ireland by providing a progressive childcare subsidy and that this would reduce barriers to labour force participation, among other objectives.

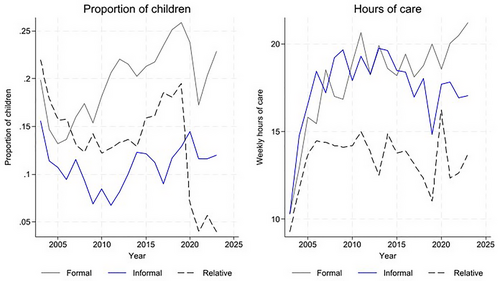

The NCS is a subsidy for users of formal childcare. Formal, for the purposes of the subsidy, means that the childcare provider must be registered with the state. In practice, this limits the subsidy's reach to creches and other childcare centres. So-called informal childcare, provided in the child's home or in the provider's home, is not eligible for the subsidy. Figure 2 shows the proportion of children under 13 who used each type of care between 2003 and 2023, as well as the average hours used by children in each type of care. The proportion of children in formal care increased dramatically after 2010, when the free pre-school year was introduced. This was accompanied by a reduction in the number of children in informal care. Another sharp increase in formal care usage is visible between 2016 and 2019, the roll-out period for the NCS, although this is accompanied by a similar increase in the usage of informal care and may be partly attributable to increased labour force participation in the recovery period from the financial crisis. Average hours of care in formal and informal settings were relatively similar until 2016 when the average hours used in informal care settings dropped compared to formal settings.

The NCS has two main components: the universal subsidy and the income-assessed subsidy. The income-assessed subsidy is further available in two forms: the standard hours subsidy and the enhanced hours subsidy. Parents can only receive one of the subsidies per child; that is, a parent receiving the more generous income-assessed subsidy cannot also receive the universal subsidy. No payments are made directly to parents under the NCS: subsidies are paid to the childcare provider and subtracted from the fee charged to parents.

In 2017, when the NCS was announced and the universal component was introduced, the universal subsidy was targeted at children aged over 24 weeks and under three years of age, in registered childcare. It consisted of a subsidy of €0.50 per hour of childcare per child, up to a maximum of 40 hours. The universal subsidy is not means-tested and predominantly benefits higher-income households. The maximum monthly universal subsidy was €87 in 2019. This puts it at 9 per cent of average full-time formal childcare costs at the time.6

The income-assessed subsidy, which is the first policy reform analysed in this paper, was introduced in November 2019 and was originally targeted at children aged over 24 weeks and under 15 years of age in registered childcare. The subsidy varies based on parental employment/educational status. In 2019, if both parents were in work, education or training, the household was entitled to up to 40 hours per week of subsidised childcare. If at least one parent was not in work, education or training, the household was entitled up to 15 hours per week. Additionally, the claimant household must have had a ‘reckonable income’ of less than €60,000 a year7 with the subsidy subject to graduated withdrawal for reckonable incomes below €60,000 but in excess of €26,000 a year. The maximum subsidy rate was €3.75–5.10 per hour of care, with higher rates applying to younger children. The hourly rate was tapered as household reckonable income increased between €26,000 and €60,000 per annum. Doorley et al. (2023b) argue that the withdrawal rate of the NCS between these two income points (which is especially steep for families with multiple eligible children) provides a disincentive to earn or work more. They estimate that almost one-fifth of workers eligible for the NCS face a marginal effective tax rate (METR) of more than 60 per cent. The theoretical effect of this reform on mothers' labour supply is, therefore, ambiguous as it may incentivise them to join the labour market to avail of the subsidy or to reduce their labour supply in order to satisfy the means test.

Since its introduction, the maximum number of hours eligible for subsidy has increased to 45 per week (or 20 per week for parents who are not in work) and, since 2022, hours of free pre-school and school are no longer deducted from this total. In 2022, the universal component of the scheme was extended to children up to age 15 and, in 2023, it was increased from €0.50 to €1.40 per hour of formal childcare. This latest increase is more likely to increase the financial incentive for mothers to work or to work more as it is not withdrawn with income.

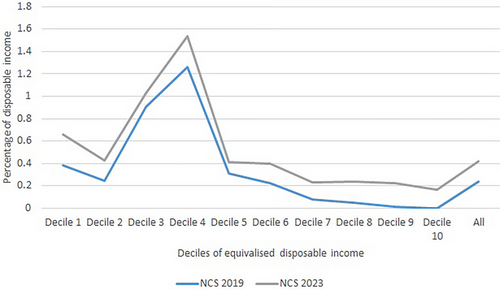

Figure 3 shows the distributional impact of each reform compared with a scenario of no childcare subsidies.8 The roll-out of the income-assessed subsidy in 2019 mainly benefits low-income households, representing up to 1.2 per cent of disposable income for households in decile 4 and 0.2 per cent of disposable income, on average. The increase in the universal subsidy in 2023, from €0.50 to €1.40 per hour and its extension to children aged up to 15, benefits households throughout the distribution, increasing the average impact of the NCS to 0.4 per cent of disposable income across the population.

Figure A.1 in the online Appendix shows the evolution of childcare as a sub-index in the Irish Consumer Price Index (CPI). Noticeable decreases in the out-of-pocket cost of childcare can be observed in 2010 (following the introduction of free pre-school) and in 2023 (following the expansion of the NCS). A levelling-off of prices is observable between 2017 and 2019, when the NCS was rolled out.

2.3 Quality of childcare

Much international evidence points to the importance of childcare quality for child outcomes and in encouraging parents to join the labour market. A recent report by OECD (2021b) suggests that the quality of childcare in Ireland is improving but that deficiencies remain. While investment in early childhood education and care (ECEC) was well below the OECD average in 2021, projections for future expenditure, which included the expansion of the NCS, may help Ireland to catch up in the longer term.

However, there is fragmentation in the provision of formal childcare. The introduction of the ECCE programme, which provides free pre-school for children aged 3–5 and is fully funded, has incentivised providers to focus on this age group, to the detriment of children under the age of 3. Although child–staff ratios are lower for children under 3, the staff often have less experience and lower qualifications. The OECD also highlights low wages and precarious working conditions in the formal childcare sector, resulting in high staff turnover and a relatively high administrative burden for childcare providers who are subject to inspection and regulation from a number of institutions.

Concerning the informal childcare sector, there is less evidence on childcare quality as the sector is largely unregulated. Childminders, who constitute the majority of this sector, are self-employed. In contrast, nannies are employees of the parents. Both, in principle, should be registered for tax and social security purposes. In practice, there is a large body of anecdotal evidence indicating that much of the informal childcare sector operates on the black market. As acknowledged by Frontier Economics (2020), the full size and extent of the childminding sector in Ireland is unknown. The National Action Plan for Childminding (DCEIDY, 2024) has set out a timeline for extending regulation and support to childminders. This will also allow parents of children cared for by childminders to access the NCS in the future.

3 JOINT MODEL OF LABOUR SUPPLY AND CHILDCARE CHOICE

3.1 The discrete choice model

To characterise the labour supply of mothers in Ireland, we model labour supply decisions as the choice between a finite set of alternatives (Aaberge et al., 1995; van Soest, 1995; Hoynes, 1996). This approach is considered more realistic than a continuous choice set, given the constraints faced by individuals when searching for a particular set of labour supply hours. In addition to the choice of hours worked, we model the choice between formal and informal childcare for mothers who work, as in Kornstad and Thoresen (2007).

We simplify the choice set faced by mothers in two important ways. First, mothers must choose between formal, informal and parental care. Formal childcare is centre-based care and is subsidisable by the NCS. Informal childcare is that performed by a paid childminder or nanny in the childminder's or child's home.9 Parental care is that performed by the mother if she chooses not to work. If she chooses to work part-time, the mother can perform part-time parental care and use formal or informal paid care for her hours of work. Our model does not allow fathers to perform parental care. By limiting the sample to lone mothers and coupled mothers with full-time working partners, this option is excluded. It could be relaxed in future work but, given the well-documented inelastic labour supply of fathers, the restriction is unlikely to substantially affect our results. We also do not allow unpaid care by relatives or others in the model and exclude families who make use of unpaid care from the analysis as we have no information on access to this type of care for those who are not working.

Female wage rates are calculated using Heckman-corrected predictions for both workers and non-workers (model coefficients are available in Table A.1 in the online Appendix). Assuming that the error terms in the wage models are normally distributed, we add a single random error term to each wage prediction as ignoring these in a non-linear labour supply model would lead to inconsistent estimates of the structural parameters.

The cost of childcare is calculated using the usual weekly hours and cost of childcare in the SILC data. We estimate an average hourly cost for formal and informal childcare, by age of child. We calculate the total childcare cost in each counterfactual labour supply scenario by multiplying the derived average hourly cost by the childcare hours needed in each counterfactual. This cost is then subtracted from disposable income to arrive at a net-of-childcare-cost disposable income concept, . The total childcare cost is dependent on the child's age and mothers' hours worked. One complication is the cost of formal childcare for children aged between 3 and 5. These children are entitled to 15 hours of free care a week, equivalent to the free pre-school hours available in the ECCE scheme. To calculate the cost of formal childcare for this group outside of these hours, we use the average hourly cost of childcare for children aged 6–12, which is not downward-biased by the provision of free pre-school.

Deterministic utility is completed by independent and identically distributed error terms for each choice. Under the assumption that error terms follow an extreme value type I (EV-I) distribution, the (conditional) probability for each household of choosing a given alternative has an explicit logistic form, which is a function of deterministic utilities at all choices. The unconditional probability is obtained by integrating out the disturbance terms (unobserved heterogeneity and the wage error term) in the likelihood function. In practice, this is done by averaging the conditional probability over 50 draws, and the simulated likelihood function is maximised to obtain all estimated parameters (Train, 2009).

Identification of the model rests on the various non-linearities, non-convexities and discontinuities in household budget constraints caused by the interaction of tax–benefit policies with household circumstances (see van Soest, 1995; Blundell et al., 2000; Bargain, Orsini and Peichl, 2014). Two mothers with the same gross wage can end up with different net income, due to their different individual and household characteristics (age and number of children, marital status, accommodation type, disability, non-labour income, hours of work, etc.). These individual and household circumstances result in different individual marginal tax rates and benefit withdrawal rates. The cost of childcare – another source of variation that is deducted from household disposable income – is calculated based on the child's age, hours used and the form of care. Importantly, the determinants of this translation from earnings to net-of childcare-cost disposable income are more complex than the simple taste-shifters used in the labour supply model due to the many interactions between earnings, hours of work and household characteristics in the tax–benefit system.

3.2 Data

We use the Irish microsimulation model SWITCH – described and validated in Keane et al. (2023) – linked to the Irish component of the SILC in 2019, which contains administrative information on earnings and welfare from the Irish Revenue Commissioners and the Department of Social Protection. It also contains detailed information on typical childcare usage and cost (see Table B.1 in the online Appendix for details of survey questions).

We restrict the sample to mothers aged 18 and over whose youngest child is 6 or under and whose partner (if they have one) works full-time – defined in this case as 35 hours or more per week. We drop households who are using unpaid childcare, such as relatives. This simplifies the childcare requirements of mothers in our sample in any counterfactual simulations. A mother working full-time whose partner is also working full-time is likely to need full-time paid childcare as long as their youngest child has not yet started school.

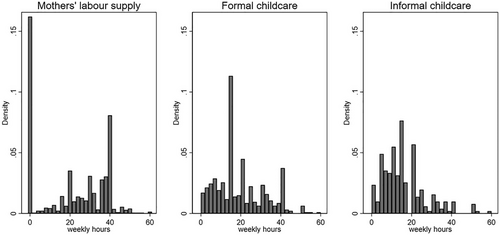

Figure 4 shows the distribution of hours worked by the women in the sample as well as the distribution of formal and informal childcare hours used.13 The typical spikes in labour supply are observable at 0, 20, 30 and 40 hours per week. The most frequent labour supply choice is non-participation, followed by full-time (40 hours per week) and part-time (20 or 30 hours per week). In our model, we discretise actual hours work as follows: 1–16 corresponds to 16 hours, 17–32 corresponds to 32 hours and 33 corresponds to 40 hours.

Formal childcare hours are concentrated around 15 hours per week (the universal pre-school hours for children aged 3 and 4). There are also noticeable density spikes at 20 and 40 hours per week. This is likely to partly reflect the demand for part- and full-time childcare, but also rationing by childcare providers, which, in many cases, leads to them offering only part-time or full-time options. The distribution of informal childcare hours, by contrast, is more evenly spread. There are multiple spikes observable around 5, 10, 15 and 20 hours but there are also plenty of observations in between these levels, suggesting that informal childcare may be more flexible in terms of hours of use. Previous work by Doorley et al. (2023a) indicates that hours of work (for both mothers and fathers) are higher for children in informal care. This care option may therefore be more appealing to parents who work longer hours through irregular or shift work. For this reason, we ration formal childcare in the discrete choice model such that only 15, 20 or 40 hours of formal childcare are possible (and the number of hours used must be greater than or equal to the number of hours of labour supplied by the mother). We allow informal childcare to be more flexible, with the hours used corresponding exactly to the number of hours worked by mothers.

Table 1 describes income and childcare of mothers in our sample, separated by the type (if any) of childcare used. Given the focus of this paper on subsidies for formal childcare, if a household uses both formal and informal childcare, we categorise these parents as formal childcare users.14 We group lone parents and married or co-habiting mothers together to report these statistics, as the sample size for lone parents prevents detailed reporting of descriptive statistics.15 Average household market income is higher for mothers who use formal and informal childcare – at €1,599 and €1,803 per month, respectively – but it is much lower for households who do not use childcare (€799 per week). This is consistent with the latter not engaging in paid work on the labour market. Average hours worked by mothers using formal (31 per week) and informal (32 per week) childcare are reasonably similar. Average hours of paid childcare used, which counts the sum of hours for each child in multiple child households, are slightly higher in the case of formal (32) than informal (28) childcare.16

| Childcare type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal | Informal | None | |

| Market income | 1,599 | 1,803 | 799 |

| (925) | (911) | (697) | |

| Disposable income | 1,256 | 1,372 | 766 |

| (482) | (452) | (351) | |

| Female work hours | 30.8 | 31.6 | 0 |

| (9.6) | (9.2) | (0) | |

| Hours of childcare | 31.8 | 27.6 | |

| (25.1) | (15.5) | ||

| Median hourly cost | 4.1 | 5 | |

| (3.3) | (14.7) | ||

| Mean hourly cost | 4.7 | 7.3 | |

| (3.3) | (14.7) | ||

| Total cost of childcare | 224 | 260 | |

| (127) | (107) | ||

| Disposable income: childcare cost | 1,032 | 1,121 | |

| (444) | (452) | ||

| Proportion eligible for NCS | 0.77 | ||

| (0.42) | |||

| Proportion eligible for NCS 2023 | 1 | ||

| (0) | |||

| Amount of NCS given receipt | 11.41 | ||

| (10.4) | |||

| Amount of NCS 2023 given receipt | 18.89 | ||

| (9.14) | |||

| 165 | 82 | 130 | |

| Weighted | 87,071 | 27,180 | 74,040 |

- Note: Calculations using the microsimulation model, SWITCH linked to 2019 SILC. Sample is mothers who are fit to work, whose youngest child is no older than six and whose partner (if any) works at least 35 hours per week. Monetary values are weekly unless otherwise specified.

We calculate the average hourly cost of both types of childcare and find that the median hourly cost is €4.10 for formal and €5 for informal childcare. The mean cost is also higher for informal childcare (€7.30) than for formal childcare (€4.70). We use these estimated hourly childcare rates in calculating counterfactual childcare costs when mothers change their labour supply.17 As children aged between 3 and 5 are likely to be availing of 15 hours per week of free pre-school, we proxy the hourly cost of childcare for any additional hours for this group using the average hourly cost of childcare for older children.

The average cost of childcare for households using formal and informal childcare is €224 and €260 per week, respectively. Subtracting the cost of childcare from disposable income gives the income (consumption) concept used to model labour supply and this is slightly lower for households using formal childcare (€1,032 per week) compared to informal childcare (€1,121 per week).

Simulating receipt of the NCS based on the eligibility criteria announced at the end of 2019, we find that 77 per cent of the households in our sample who use formal childcare would be eligible for the subsidy and would receive an average of €11.4 per week. Following the extension to the subsidy scheme up to 2023, this rises to 100 per cent eligibility, thanks to the expansion of the universal component of the subsidy, and an average subsidy of €18.9 per week.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Model fit

Coefficients from the labour supply model are displayed in Tables A.2 and A.3 in the online Appendix.18 Separate models are run for single mothers and married or co-habiting mothers, according to model specifications in Section 3.1. As expected, utility increases with consumption and leisure and varies with taste-shifters. Due to the size of the lone parent sample and Statistical Disclosure Controls governing the use of the underlying data, in what follows, we present results for all mothers grouped together.

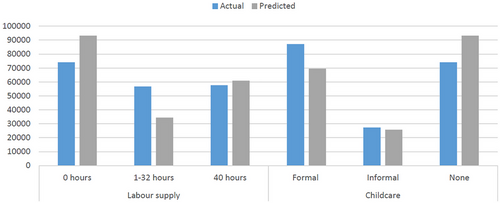

The predicted and actual labour supply choices are shown in Figure 5. Because of the small number of mothers choosing the band corresponding to 16 hours of work per week, we group this category with the next and show hours choices between 1 and 32 together. Overall, predictions are quite close to actual choices made, with mothers concentrated at 0 hours of work, followed by full-time and then part-time work. Compared to the underlying data, the model overpredicts zero hours of work compared with part-time work. Predictions for full-time work are very close to the underlying data.

Predictions for formal versus informal childcare are also quite close to the relative usage of each in the underlying data. However, as the model slightly underestimates labour supply, it also underestimates the usage of each type of childcare – particularly formal care – and overestimates the choice of no paid childcare (or parental care).

Based on the simulated choice of hours worked, we calculate the elasticity of mothers' labour supply with respect to income at the extensive margin (participation elasticities) and intensive margin (hours worked). To do this, we simulate a 10 per cent increase in childcare costs and use our model estimates to predict mothers' labour supply, accounting for this change. We find that for a 10 per cent increase in childcare costs, mothers decrease their labour market participation by 1.2 per cent, and decrease hours worked by 0.9 per cent. Dividing by 10 gives elasticities of −0.12 and −0.09 at the extensive and intensive margin (Table 2). This suggests that mothers with young children could be quite responsive to a decrease in childcare costs, particularly at the extensive margin.

| Extensive margin | Intensive margin | |

|---|---|---|

| Elasticity with respect to childcare costs | −0.120 | −0.092 |

- Note: Calculations using the models described in Section 3.1 and the microsimulation model, SWITCH, linked to 2019 SILC. Sample consists of mothers who are fit to work, whose youngest child is no older than 6 and whose partner (if any) works at least 35 hours per week. Elasticities are estimated as the percentage change in participation rates (extensive) and percentage change in expected weekly hours of work (intensive) following a 10 per cent increase in childcare costs, and are divided by 10. Source: 2019 SILC.

These elasticities are similar those found in the international literature for the US, Canada and the UK, and above what has been estimated for Germany, France and Norway. Research for the US and Canada estimates participation elasticities of married women of −0.16 (Michalopoulos and Robins, 2002). For the UK, Blundell et al. (2000) estimate participation elasticities of −0.08 to −0.07 for married women while Viitanen (2005) obtains a price elasticity of participation of −0.14 for men and women. Wrohlich (2004) considers the effect of childcare costs on the labour supply of married women and mothers, respectively, in Germany, finding very small participation and hours elasticities ranging from −0.02 to −0.09. Choné et al. (2003) obtain cost elasticities of participation and hours worked of −0.01 (−0.01) and −0.02 (−0.01), respectively, for French married women with children under 3 (between 3 and 7) while Thoresen and Vatto (2019) find participation and hours elasticities close to zero for Norway.

4.2 Simulating childcare subsidies

Using estimates from the labour supply models for married or co-habiting mothers and lone mothers (model coefficients displayed in Tables A.2 and A.3 in the online Appendix), we next investigate the labour supply effect of several alternative childcare subsidy reforms. In each case, we treat the subsidy for childcare as income, adding it to disposable income net of childcare costs. This requires the explicit assumption that childcare providers do not change their prices in response to the subsidy and that parents consider the reduction in childcare costs in a similar manner to extra income. Altering the net income under each counterfactual scenario allows us to compute a new utility maximising choice for each household and, by comparing to the baseline scenario, we can estimate how labour supply changes in response to the reform.

We simulate four childcare reforms. Reform one introduces the income-assessed component of the NCS, a means-tested subsidy for some users of formal childcare using the parameters of the subsidy, as introduced at the end of 2019. In simulating the behavioural response to this subsidy, we must assume that there are no anticipation effects; that is, the parents we observe in the 2019 data have not already altered their behaviour in anticipation of the new subsidy, which was announced in 2017. If there are anticipation effects, our estimate is a lower bound of the true behavioural response. Reform two extends this subsidy to those who use informal childcare as well as formal childcare. Reform three replaces the NCS with the most recent, and more generous, parameters of the subsidy for formal childcare only. The key parameter changes include an increase in the maximum hours of subsidy to 45 (or 20 for non-working parents), an increase in the hourly universal subsidy from €0.50 to €1.40, an increase in the number of subsidisable hours for pre-school and school children, and its extension to children up to age 15. Reform four extends this subsidy to users of informal childcare, a potential reform recently mooted by the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (DCEIDY).19 In each case, we assume that there are no demand-side reactions to the subsidy; that is, childcare providers do not change the price of childcare in response to the policy changes and there is always sufficient supply to meet demand. This is likely to be a simplification, as recent work by Narazani et al. (2022) indicates that parents in Ireland face substantial unmet need in formal childcare.

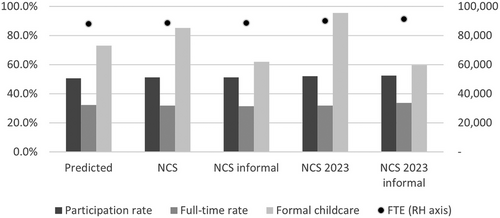

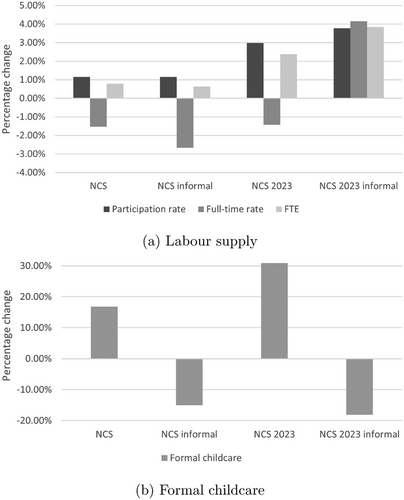

Figure 6 (and Table A.4 in the online Appendix) shows the effect of each of these reforms on childcare usage and labour supply, compared to the baseline 2019 prediction. In the baseline, the predicted participation rate of mothers in our sample is 51 per cent, with the full-time rate estimated at 32 per cent. Formal childcare usage is estimated at 73 per cent and the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) workers is around 87,998.20

Figure 6 also shows how introducing the 2019 parameters of the NCS and the more generous 2023 parameters affects mothers' labour supply and the demand for formal childcare. Figure 7 shows this in more detail, focusing on actual and hypothetical NCS reforms and indexing the baseline model predictions of mothers' labour supply and demand for childcare at 100.

We estimate that the 2019 system of NCS increases mothers' participation rates by 1 per cent (or half a percentage point) but decreases their full-time rate, by 2.5 per cent (or half a percentage point). This can be attributed to the means-tested nature of the subsidy, which encourages labour force participation, through cheaper childcare, but discourages earning over the income threshold.

Introducing the 2023 NCS policy results in an increase in the participation rate of mothers by 3 per cent (1.5 pp), compared to a no-subsidy baseline, with the FTE increasing by a similar proportion. There is a significant increase in the demand for formal childcare compared with informal childcare as a result of the subsidy in each scenario.

With the most recent NCS parameters, demand for formal childcare reaches almost 100 per cent. This reflects the underlying trade-offs captured by the labour supply model between the cost and flexibility of each kind of childcare. Although demand for formal care reaches almost 100 per cent in this NCS 2023 scenario, capacity constraints and other frictions which are impossible to capture using the survey data underlying the SWITCH model will almost certainly lead to continued usage of some informal care.21

In a last set of simulations, we extend the parameters of the 2019 and 2023 NCS policies to informal childcare. The labour supply effect of this extended NCS for the income-assessed subsidy is similar to the formal childcare-only NCS, although the demand for formal childcare decreases substantially. This signals a limited additional labour supply effect but a reallocation between formal and informal care. Extending the increase in the universal subsidy for childcare to informal care does however increase labour supply (particularly full-time rates) in addition to reducing the demand for formal childcare.22

We test the sensitivity of our results to the model specification and to the sample of mothers selected. Results for a more harmonised model specification between couples and lone parents are available in the online Appendix (Figure C.2) while results for a larger sample of mothers (whose youngest child is under 12 years of age) are available in Figure D.3.23 These two sets of results confirm (i) the increase in labour supply as a result of the introduction and extension of the NCS and (ii) the increased demand for formal care when informal care does not attract a subsidy.

4.2.1 Exchequer effects of childcare subsidies and behavioural responses

Table 3 reports the net exchequer effect of the simulated reforms for the sample of families with children under 6 and full-time working fathers (in the case of couples).

| NCS | NCS informal | NCS 2023 | NCS 2023 informal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childcare subsidies: | ||||

| before behavioural response | 200.56 | 290.52 | 374.91 | 535.61 |

| after behavioural response () | 307.10 | 334.65 | 580.63 | 597.00 |

| Change in tax revenue () | −13.65 | −13.83 | −15.90 | 12.90 |

| Change in welfare expenditure () | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.43 |

| Net exchequer impact () | −320.76 | −348.48 | −596.53 | −584.53 |

| Effect of tax and welfare () | 4.45% | 4.13% | 2.74% | −2.09% |

- Note: Authors' own calculations using the 2019 SWITCH policy linked to 2019 SILC data. Sample is restricted to mothers, whose youngest child is under 6 and who are available for the workforce (i.e. not disabled, in education or retired). In the case of partnered mothers, the sample is restricted to those with partners working full-time (at least 35 hours). The baseline scenario is no NCS. Childcare subsidies after the behavioural response take into account both labour supply and childcare type responses.

The column for each reform scenario shows how expenditure increases, accounting for the introduction of and reform to childcare subsidies and the induced change in childcare choice and labour supply of mothers.

The introduction of the income-assessed NCS in 2019 increases government expenditure on childcare subsidies for our subsample to €201 million per annum in a morning-after setting. However, the childcare behavioural response – a shift from informal to formal care – adds a further €120 million to the cost. Most of this extra cost comes from the fact that changing labour market behaviour leads to higher eligibility for the subsidy. However, the decrease in the full-time rate of mothers also decreases tax revenue by €13.65 million (or 4.5 per cent of NCS expenditure), leading to a net exchequer loss of €321 million per annum.

Simulating the effect of the 2023 NCS leads to higher government expenditure on childcare subsidies. The corresponding decrease in tax revenues, as a result of the decrease in full-time work, is relatively smaller in this scenario, increasing the cost of the NCS by 2.7 per cent.

In general, extending the NCS (either the 2019 or 2023 version) to informal childcare increases the cost. In the case of the 2023 NCS, extending it to childminders results in an increase in full-time rates of mothers (as well as participation rates). This leads to an increase in the tax take. As such, this is the only reform scenario in which the behavioural response somewhat mitigates the increased cost of the subsidy, reducing it by 2.1 per cent.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper has investigated how childcare costs affect the labour supply of mothers of young children in Ireland. Ireland presents a relatively unique case study, combining a strong history of gender inequality and low female labour supply with very high childcare costs, which have only recently been tempered by significant and wide-ranging childcare subsidies.

Using a discrete choice labour supply model, which is extended to allow a choice between formal and informal childcare, we model the labour supply of mothers with children who are not yet of school age. We find that their labour supply is quite sensitive to childcare costs. We estimate elasticities of labour supply with respect to childcare costs of −0.12 and −0.09 at the extensive and intensive margins, respectively. These elasticities are similar to those found in the international literature for the US, Canada and the UK, and above what has been estimated for Germany, France and Norway.

We model the effect of the introduction of the NCS in Ireland at the end of 2019. This scheme subsidises users of formal childcare through both universal and means-tested payments. We estimate that the means-tested component of the scheme significantly increased the demand for formal childcare and increased the labour market participation of mothers of young children by half a percentage point. We estimate that an increase to the generosity of the universal component of the policy, which came into effect in 2023, will further increase labour supply by increasing the full-time rate of mothers with young children by 1 pp.

However, this latest reform is likely to put pressure on the supply of formal childcare. Because informal childcare is not currently subsidised by the NCS, increasing its generosity substantially depresses the demand for informal childcare. However, if the government-proposed extension of the NCS to informal childcare providers goes ahead, this is likely to further increase female labour supply and restore demand for informal childcare. The regulatory requirements that providers of informal childcare will have to meet in order to be eligible for this extension also have the potential to increase the quality of childcare in Ireland.

Simulating the exchequer cost of reforms to the NCS, we find that behavioural responses tend to increase it. In particular, the switch from informal to formal childcare as a result of subsidies for the latter puts upward pressure on the exchequer cost. There is a small mitigating effect from increased tax in the most generous reform scenario examined, as a result of mothers increasing their labour supply in response to more generous childcare subsidies.

Putting these results into context, it is not always the case that the introduction of a childcare subsidy increases maternal labour supply. Some subsidies include an element aimed at home or parental care and these, such as the Norwegian home care allowance and the French Prestation d'Accueil du Jeune Enfant, have been shown to decrease maternal labour supply (Kornstad and Thoresen, 2007; Muizon, 2020). Alternatively, in a context with heavily subsidised home and non-home care, increasing the subsidy on a particular type of childcare may result only in a reallocation between childcare types, with no effect on maternal labour supply. Such was the case in Finland where Räsänen and Österbacka (2024) show that subsidising private childcare does not affect maternal labour supply but does affect the demand for private (compared with public or home) care. Vattø and Østbakken (2024) suggest, in their study of means-tested childcare subsidies in Norway, that where both parental employment and participation in formal childcare are high, means-tested childcare subsidies may actually decrease parental labour supply.

More similar to the Irish context is the introduction of the Law on Childcare in the Netherlands in 2005, which resulted in a three-fold expansion in childcare subsidies over a five-year period and increased maternal labour supply by 2.3 pp at the external margin and 1.1 hours per week at the internal margin (Bettendorf, Jongen and Muller, 2015). An experimental study for Switzerland shows that childcare subsidies increase maternal labour supply once they cover 25 per cent of total childcare costs and that the marginal effect of extra subsidies decreases after this point (Zangger, Widmer and Gilgen, 2021).

In the Irish setting, we find that the elasticity of mothers' labour supply with respect to childcare costs is at the upper end of what has previously been found in countries with similar reliance on private childcare provision in their histories (such as the UK, the US and Canada). Using childcare subsidies as a tool to increase female labour supply in this context is an effective strategy. However, our analysis shows that means-testing subsidies based on household income may decrease the labour supply of mothers whose partners work full-time, in order not to exceed the income limits. We also show that, given the sizeable minority of children in Ireland who are cared for outside of a formal childcare centre, extending existing childcare subsidies to this type of provision would relieve the pressure on formal childcare places while further increasing female labour supply

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Paul Deveraux, Chrstopher Jepsen, Denisa Sologon, Iva Tasseva, Martina Zanela, participants of the IEA Annual Meeting 2023, LAGV Public Economics Conference 2023, EUROMOD Annual Workshop 2023 and ESRI seminar series for their comments. The results presented here are based on the ESRI's tax-benefit model, SWITCH version 5.3 which makes use of the EUROMOD platform. Originally maintained, developed and managed by the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), since 2021 EUROMOD is maintained, developed and managed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission, in collaboration with EUROSTAT and national teams from the EU countries. We are indebted to the many people who have contributed to the development of EUROMOD. The results and their interpretation are the authors' responsibility. We are grateful to the Central Statistics Office (CSO) for providing access to the Survey of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) Research Microdata File, on which the SWITCH tax-benefit model is based. This work was carried out as part of the ESRI's Tax, Welfare and Pensions work program. Funding from the Department of Social Protection, the Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth, the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, the Department of Health and the Department of Finance is gratefully acknowledged.

Open access funding provided by IReL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from https://www.cso.ie/en/aboutus/lgdp/csodatapolicies/dataforresearchers/ with the permission of the CSO.

REFERENCES

- 1 For a two-earner couple with two children (aged 2 and 3) in full-time care, the out-of-pocket childcare costs amounted to more than one-third of women's median full-time earnings in Ireland in 2019, which was one of the highest ratios in the OECD (OECD, 2020). In addition, the average monthly fee for full-time childcare for children under 3 in Ireland was estimated to be €771 in 2019, which is among the highest in the European Union (Motiejunaite-Schulmeister, Balcon and de Coster, 2019).

- 2 Official Census figures for ‘gainful occupation’ are even lower, at only around 7 per cent (Flood and Hardy, 2013, p. 194); however, Fahey argues that these figures underestimate supply of labour by women in and around the home (e.g., on family farms).

- 3 This labour market environment was itself a product of both legal obstacles and cultural opposition to maternal employment. For example, until 1973 female civil servants were obliged to resign upon becoming married (the so-called ‘marriage bar'); and the Constitution of Ireland, enacted in 1937, still contains a passage requiring the State ‘to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home’ (Bunreacht na hÉireann, 2018, article 41.2, p. 4, https://www.ihrec.ie/app/uploads/2018/07/IHREC-policy-statement-on-Article-41.2-of-the-Constitution-of-Ireland-1.pdf).

- 4 O'Kane (2004) summarises the sequence of reports, white papers, frameworks and national strategies set out during the period.

- 5 These ‘legacy schemes’ are the following. (i) The Community Childcare Subvention (CCS) scheme and CCS Plus, 2007 to 2021, provided support to low-income parents (particularly social welfare recipients) to obtain lower childcare costs from certain providers. As it replaced existing grants to community childcare providers, the biggest criticism of the CCS scheme was that it left most such providers worse off monetarily (O'Donoghue Hynes and Hayes, 2011). (ii) The After-School Child Care (ASCC) scheme, 2015 to 2021, provided subsidised childcare to parents claiming unemployment benefits or in-work benefits (the Working Family Payment) who increased their hours of work. (iii) The Childcare Educational and Training Support (CETS), 2014 to 2021, provided capped daily childcare rates for parents completing approved vocational and training courses or finishing secondary-level education. (iv) The Community Employment Childcare (CEC) programme provided capped daily childcare rates for parents in the Community Employment Scheme. (v) The Early Childcare Supplement (ECS), 2006–2009, was a universal supplement of €1,000 a year, paid monthly, towards childcare costs for eligible families. In contrast to the support discussed above, the ECS was not targeted: it was paid to all eligible families even if they had no intention of using it to pay for formal childcare or, indeed, of using formal childcare at all. The policy was criticised for being costly and was discontinued in the aftermath of the financial crisis. For more detail, see Russell et al. (2018).

- 6 Using SILC 2019, average hourly costs for formal childcare are €4.70.

- 7 ‘Reckonable income’ in this context means net of taxes, social insurance contributions and social welfare payments; with the exception of allowable deductions (see the NCS, https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/education/pre-school-education-and-childcare/national-childcare-scheme/). Furthermore, reckonable income is subject to a multiple child discount: if there are two children aged under 15 in the household, the household can deduct €4,300 from reckonable income, and if there are more than two children aged under 15 in the household, the household can deduct €8,600 from reckonable income.

- 8 The impact of each reform is averaged over the whole population in order to build up a distributional picture (including the population with no children).

- 9 The SILC data do not allow us to distinguish between these two types of informal care.

- 10 Actual choices are classified as follows: 1–16 corresponds to 16 hours, 17–32 corresponds to 32 hours and 33 corresponds to 40 hours.

- 11 The fit of the model is improved by the introduction of fixed costs of work, estimated as model parameters as in Callan et al. (2009) and Blundell et al. (2000). Fixed costs explain the fact that there are very few observations with a small positive number of worked hours.

- 12 This is partly because the sample size for lone parents is relatively small and a model with many taste-shifters would not converge. There is also an economic rationale for the inclusion of some variables in one model rather than the other. For example, we include an ‘urban’ and ‘irish’ dummy in the lone parent model to capture access to formal care (which, being centre-based, is more common in urban areas) and to the potential presence of extended family who could help with childcare, which is more important for single parents than for mothers with partners.

- 13 We exclude zeros from the childcare graphs for ease of exposition. Figure A.2 in the online Appendix shows the same charts with these zero observations included.

- 14 Note that 7 per cent of the sample use both formal and informal childcare so we expect this simplification to have a small impact on our estimates.

- 15 The Statistical Disclosure Controls of the Irish Central Statistics Office require that we do not report averages where the sample size is and that we do not report percentages where the sample size is .

- 16 Given the small size of the sample of mothers with young children in the SILC data, we compare these descriptive statistics with other available sources. The Ipsos Childcare Survey of Parents surveys a representative sample of children in 2022. Usage of formal childcare is similar in SILC compared with the Ipsos survey (Doorley et al., 2023a). The most recent Census of the population in Ireland also reports childcare usage. Among the paid childcare options, 60 per cent of children in paid childcare are in a formal setting compared to 40 per cent in informal care. This aligns with the statistics for paid childcare options reported in this work (67 per cent formal and 33 per cent informal).

- 17 We calculate average childcare costs by age of the child (3, 3–6 and 6) and use these to estimate childcare costs in each counterfactual simulation. As some of the samples used to calculate these costs violate the Irish Central Statistics Office's Statistical Disclosure Controls, we do not report them here.

- 18 Estimations are carried out in Stata using the user written command mixlogit (Hole, 2007).

- 19 In this research, informal childcare includes childminders who work in their own home and nannies who work in the child's home as these are indistinguishable from each other in the SILC data. It is likely that the reform proposed by DCEIDY will extend only to childminders who work in their own homes, who constitute the majority of informal childcare.

- 20 The actual rates are 61 per cent participation, 31 per cent full-time, 76 per cent formal childcare and 99,548 FTE workers.

- 21 We do not show the proportion of children in informal care as, for some simulations, the number violates statistical disclosure controls.

- 22 This simulation also allows informal carers to avail of 15 hours per week of the ECCE subsidy for pre-schoolers aged 3–5.

- 23 Model coefficients for more harmonised specification can be found in Tables C.1 and C.2.