Far from Well: The UK since COVID-19, and Learning to Follow the Science(s)*

Abstract

This paper offers a five-part framework for assessing why the United Kingdom has coped poorly compared with peer countries with the medical, social and economic challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic – a surprising failure, given the strength of its scientific community and the internationally attested quality of its civil service. The paper also offers a proposal for how to shape an independent inquiry, one promised by the UK Prime Minister, of the kind that has the primary motivation to better prepare the country for future crises. The paper begins by providing various metrics that set out how the UK has, as of late 2020, been particularly adversely affected by the pandemic. It then details the five-part framework, which is presented as a series of propositions with initial supporting evidence that require more thorough investigation, supported by a fuller record of evidence. First, we suggest that there have been problems as to how evidence about the pandemic and its anticipated effects was collected, processed and circulated, weakening policymakers’ ability to evaluate the risk calculus. Second, particular structures and processes of government decision-making appear to have been inadequate and ill-suited to the multidimensional challenges brought by the pandemic. Third, the role of political leadership and decision-making in the public health and broader policy responses needs thorough evaluation. Fourth, we assess some aspects of economic policymaking during the pandemic. Fifth, features of the UK's institutional make-up may have been a driver of the suboptimal outcomes. Overall, we argue that UK policymakers may have over-relied on the medical sciences at the expense of other (social) scientific evidence.

I. Introduction

The UK's dismal response to COVID-19 so far is surprising, given that the country is home to one of the richest clusters of scientific expertise anywhere in the world. The successes of the Oxford Vaccine Group, among other scientific innovations, are testaments to this excellence. Moreover, in October 2019, the UK was ranked second in the world for pandemic preparedness by the Global Health Security Index.1 In the same year, its civil service was assessed as the best in the world by the first comprehensive index of its kind.2

Yet this apparently first-rate capacity does not seem to have translated into outcomes. A future independent public inquiry with a rigorous mindset and access to the full range of evidence will be needed to get to the bottom of this failure. In this paper, we can only undertake preliminary explorations, designed to throw up some of the questions such an inquiry should address.

Who made the key decisions? How did policymakers weigh up different kinds of evidence? Why was information presented to the public as it was, and what alternative communication campaigns were rejected? Why were public bodies assigned particular policy challenges, and what led to such regular political intervention to change institutional involvement? Which of the UK's institutions – medical, social, policymaking or operational – lacked the capacity to absorb the pressures created by the pandemic?

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, UK government ministers have insisted that they are ‘following the science’. But, as many have pointed out, this refrain is unhelpful and misleading. A hallmark of scientific inquiry is disagreement among the scientific community: theories are presented in order to be tested, and the significance of new pieces of evidence is hotly debated. The advice that scientists give is not set in stone: scientific ‘knowledge’ is a bundle of uncertainties and disagreements, which scientists should seek to explain while offering advice on various possible courses of action and their anticipated effects.

It is the job of politicians and other policymakers, meanwhile, to explore and weigh up different kinds of evidence, before deciding on which policies to pursue. The term ‘following the science’ elides a core process of democratic government, which involves elected officials making decisions in uncertain environments – decisions that will inevitably have consequences in terms of the distribution of gains and losses (or the distribution of relative losses) across society.

This article presents preliminary propositions as to why the UK has experienced the 2020 coronavirus crisis so severely compared with peer countries. We argue that there were some pre-existing constraints and weaknesses, such as in the UK's low hospital capacity. But more broadly, we show that a significant driver of policy failure has been policymakers’ deference to the medical sciences, which came at the cost of not taking account of views from other parts of the scientific community, notably from the social sciences.

We base our argument about the weak UK COVID-19 response on our examination of five key elements:

- the collection of evidence;

- structures and processes for handling the pandemic;

- political leadership;

- economic policy; and

- the role of institutions.

Our argument is presented as a series of propositions to be subjected to further testing when more evidence is made available. We are also mindful that the end of 2020 will not be the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and that, as circumstances change, it may be possible to reach different conclusions about the effectiveness of the UK response. The conclusion sketches out what we believe an optimal investigation could look like: one whose primary aim would be the reform of key state institutions and processes, rather than one assigning degrees of blame to certain decision-makers and bodies. Although the people in charge must and will be held to account for their decisions, we appeal for open, inquisitive and fair dialogue, and hope that a blame game can be avoided, at least at the inquiry stage.

II. A comparative assessment of the British experience so far

Assessing a country's relative performance in responding to COVID-19 is not straightforward. To begin with, the quality and availability of data vary between countries. We have chosen three measures that we believe to be among the more robust, but acknowledge there are many others available. These are excess death rates, changes in GDP and subjective well-being. We explain why we believe each of them is useful, and then comment on how UK outcomes compare with those of other countries.

2.1 Excess deaths

Excess death rates during the COVID-19 pandemic provide a measure of the virus's impact on mortality that allows international comparisons to be made which are less subject to distortion than other measures of COVID-related death. The numbers directly attributed to the virus in different countries depend, for example, on the level of testing, and the time between a positive test and death, since different countries apply different cut-off dates.

Excess deaths are also a particularly useful indicator of the extent to which different countries’ health systems were put under strain during COVID-19, leading to compromises in healthcare such as cancelled operations and increased ambulance and accident & emergency (A&E) waiting times.3 The measure captures the effect such strains may have had on, for example, deaths from operable cancers.

Deaths may also be increased by other features of a country's pandemic experience – for example, if the government's public communication campaign around COVID-19 has led to a reduction in people's use of health services. All in all, excess death rates are a particularly useful measure of a country's overall performance in the pandemic, capturing both the effects of policy decisions that change the prevalence of the virus (such as the stringency of lockdowns) and the capacity and preparedness of the healthcare system to respond to a major shock.

Deaths from all causes during the pandemic, per million population, are compared with averages over a recent period: researchers have typically taken 2015–19 as the baseline where country-level data are good enough. Although, since the start of the pandemic, countries have moved up and down this dismal league according to where they are along the waves of the COVID-19 cycle, the message is clear: the UK has so far consistently displayed one of the highest excess death rates, both per million people and compared with historical averages, when measured against countries of similar income and levels of development.

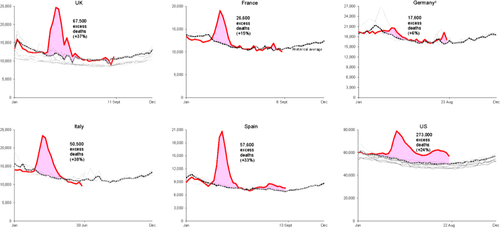

To take just one snapshot, analysis of mortality data by the Financial Times in September 2020 shows that the excess death rate in the UK is +37 per cent in 2020 compared with the average death rate over 2015–19. This compares with excess death rates of +15 per cent in France, +6 per cent in Germany, +38 per cent in Italy, +33 per cent in Spain and +24 per cent in the United States.4 These excess deaths data, and associated averages over recent periods, are shown in Figure 1.

Deaths per week, and excess deaths in 2020

aIn 2016–17 and 2017–18, Germany saw very high influenza-related deaths (estimated at 22,900 and 25,100 respectively; see Robert Koch Institut, 2019, 47). Germany's excess death rate in 2020 is lower than it would have been had these pre-2020 years not seen particularly high death rates.

Note: The thick solid lines show deaths per week from all causes in 2020. The multiple paler lines in each graph show the same in the years 2015–19 for Italy, the UK and the US, 2016–19 for Germany and Spain, and 2018–19 for France. The dark dashed lines show averages over these periods. The shaded areas show excess deaths in 2020 above these averages.

Country-specific demographic, economic and social factors may account for some of these differences. However, many argue that the reason for the UK's notably poor performance in the first phase is that the decision to lock down was taken too late.5 Others have pointed to London's role as an international hub, which meant that it has been particularly vulnerable to cross-border transmission of the virus. Questions have also been raised about early policy decisions – for example, the discharge of elderly patients from hospitals into care homes without adequate testing in place – which in turn may reflect the degree of pressure on relatively limited health services. While statistics for hospital provision in different countries should be compared with caution, World Health Organization data for the ratio of hospital beds to population suggest the UK is well below the European average.6 In time, we will learn how much weight to give to each of these variables. This article offers preliminary insights into where we might look for answers.

2.2 Changes in GDP

As the journalist Evan Davis put it on the BBC Radio 4's PM programme, ‘measuring GDP at a time like this is like measuring a patient's cholesterol after he has been hit by a bus’. Although the utility of GDP measures is open to question, we have included this metric because it provides the most widely recognised method of assessing economic performance.

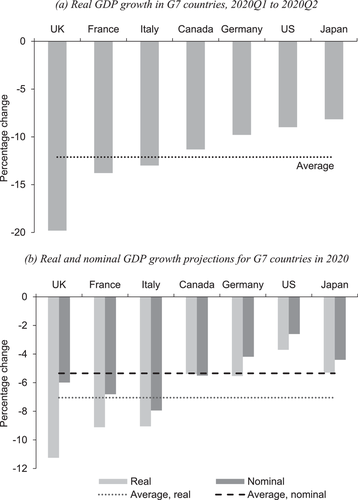

Comparative GDP data released by the OECD indicate that UK economic performance fared particularly poorly during the pandemic, with the sharpest decline in both real quarterly (–19.8 per cent) and projected annual (–11.2 per cent) growth among the G7 nations. As Figure 2 shows, the economy with the next most dramatic fall in GDP in real terms was France (–13.8 per cent quarterly change; –9.1 per cent annual change). The shock to the UK economy, at least according to real GDP, is far worse than the average among OECD countries and EU member states. These estimates of real change in GDP are adjusted for inflation; however, measured by GDP in nominal terms, the UK is not such an outlier, as shown in Panel b of Figure 2. The reasons for these measurement differences are not straightforward. But the figures point to the extremely tough and uncertain road ahead for the UK to return to sustained growth.7

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, December 2020.

The hit to the UK economy may reflect the length and stringency of its lockdowns, and the fact that services, which account for a comparatively high portion of the economy, have been especially hit by physical distancing measures.8 However, causes of the dramatic falls in household spending in the UK, despite its relatively high adaptation to online shopping, are harder to pin down.9 Was the level of anxiety higher and, if so, did that stem from worries about health service capacity or the government's communications strategy? Or from other socio-economic factors?

The decline in GDP in part reflects government decisions to close down substantial parts of the economy. So we should be cautious about applying conclusions derived from previous recessions, since one effectively induced by government is likely to have very different effects. As new epi-macro models have shown, so much also depends on how well further outbreaks of COVID-19 are suppressed, the speed and success of vaccination programmes, and various economic policy decisions.10 Considerable uncertainties remain about what kind of recovery can be hoped for in 2021, but it is difficult not to be pessimistic about the UK's economic outlook, especially given the prolonged uncertainties surrounding Brexit. Some evidence points to a V-shaped recovery, but even so with a loss of output that may not be recovered for many years.

2.3 Subjective well-being

The third and final metric that we consider to be key to understanding the impact of the pandemic is subjective well-being. In the UK, this is calculated by asking people to evaluate, on a scale of 0 to 10, how satisfied they are with their life overall; whether they feel they have purpose and meaning in their life; and about their emotions (happiness and anxiety) during a particular period. Table 1 shows the declines in all markers of subjective well-being in the second quarter (Q2) of 2020 – the first time since the Office for National Statistics (ONS) began collecting data in 2011 that they all worsened significantly on the year before. The only decline on this scale in recent data is the collapse in well-being in Greece in the wake of the 2008 crisis, following the crippling choices that country was forced to make after its near-bankruptcy.

| Average level | Change to 2020 Q2 from: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 Q1 | 2019 Q2 | 2019 Q3 | 2019 Q4 | 2020 Q1 | 2020 Q2 (est.)a | 2020 Q1 | 2019 Q2 | |

| Life satisfaction | 7.72 | 7.67 | 7.66 | 7.67 | 7.65 | 7.01 | –0.64 | –0.66 |

| Life worthwhile | 7.89 | 7.88 | 7.86 | 7.86 | 7.85 | 7.43 | –0.42 | –0.45 |

| Happiness | 7.57 | 7.52 | 7.51 | 7.52 | 7.39 | 6.87 | –0.52 | –0.65 |

| Anxiety | 2.90 | 2.96 | 2.94 | 3.00 | 3.22 | 4.20 | 0.98 | 1.24 |

- a Calculated as an average across weeks between 27 March and 7 June.

- Source: ONS Opinions and Lifestyle Surveys, 2019–20; see https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing.

While the decline in well-being in the UK is hardly surprising, Table 2 shows that it nonetheless looks particularly severe compared with some other countries of a similar economic and development profile. Differences in collection methods mean such comparisons should be made with caution, but it will be important to investigate why the decline in the UK is so much more marked than in countries with similarly tragic experiences of the pandemic, such as Spain and Italy.

| Average level | Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–19 | 27 April – 23 August | ||

| Spain | 6.4 | 6.3 | –0.1 |

| Italy | 6.4 | 6.1 | –0.3 |

| Netherlands | 7.4 | 7.1 | –0.3 |

| France | 6.7 | 6.3 | –0.4 |

| United States | 6.9 | 6.3 | –0.6 |

| Germany | 7.1 | 6.4 | –0.7 |

| Denmark | 7.6 | 6.9 | –0.7 |

| Sweden | 7.4 | 6.5 | –0.9 |

| Finland | 7.8 | 6.9 | –0.9 |

| Australia | 7.2 | 6.3 | –0.9 |

| Canada | 7.2 | 6.3 | –0.9 |

| Norway | 7.5 | 6.4 | –1.1 |

| United Kingdom | 7.2 | 6.0 | –1.2 |

- Source: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, World Happiness Report 2020, 19, https://worldhappiness.report/; YouGov, ‘COVID-19 Public Monitor’, https://yougov.co.uk/covid-19.

There is also much to be learnt from closer examination of the UK national data. The unprecedented decline in subjective well-being preceded the first lockdown in March, at which point the indicators stabilised. Did people adapt to the ‘new normal’ and feel reassured? As COVID-19 cases began rising again in September, and new restrictions were introduced, life satisfaction dropped again, although the decline has not been as significant as before the first lockdown.11

Socio-economic factors, such as financial insecurity, may help explain why the drop has been so severe in the UK, but we stress that further research is needed. Recent work by Abi Adams-Prassl and colleagues has identified the variable effect of the pandemic on different groups in society. For example, those in more precarious jobs have been more likely to be put out of work (in the UK and the US, this means the lower-qualified and lower-paid), while school closures and increased care responsibilities have fallen disproportionately on women.12 In Germany, meanwhile, neither gender nor level of education is clearly predictive of job security.13

Research at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study have also shown how the pandemic has had a disproportionate effect on the less well-off, women and ethnic minorities with respect to health, economic factors and well-being.14 One particularly worrying effect has been the impact on children in disadvantaged groups. Pandemic effects may amplify some of the gaps in educational outcomes between rich and poor students.15

In time, we will learn which distributional effects are common to all the countries affected, and which have been particular to the UK. Meanwhile, they should be front-of-mind to government when it considers how economic support packages should be targeted.16 In Section IV, we show how the UK's rich database of well-being metrics could be used in assessing the costs and benefits of policy choices. We now turn to the way in which the UK made its initial analysis of the risks associated with the pandemic from January 2020 onwards.

III. Collecting evidence and understanding the risks

A challenge cannot be contained until it can be measured. Blind spots make it hard to come to informed decisions. A reminder of this came with the most recent (pre-COVID) major international challenge to policymakers, the 2007–09 global financial crisis (GFC), whose effects are still with us today. Many studies of the GFC have highlighted the lack of good data held by regulators on the activities of the financial sector. Since then, new regulation has gone some way to mapping the interconnectivities and financial exposures of global finance.

With the pandemic, however, we have had to learn the same hard lesson again. Policymakers appear to have lacked key evidence, and/or the ability to synthesise and act on it effectively. This is puzzling, because the UK possesses some world-class public institutions capable of generating and interpreting massive pooled data sets, which should have been able to present policymakers with well-synthesised evidence on which to base decisions as to how to respond to the crisis.

The NHS is one of these key bodies: its size and strength are regularly cited as core features that enable it to collect and act on data much more effectively than health systems in countries reliant on more private or decentralised provision. Meanwhile, the ONS is one of the most celebrated national statistical agencies anywhere in the world, which should have provided the capability to aggregate, manage and analyse health and other relevant data. Public Health England (PHE) is a more recent innovation, but (despite real-terms cuts in recent years) it is sufficiently large and well funded to be able to engage in effective collaboration with other health and statistical institutions.

By the end of January, the World Health Organization and scientific experts could be judged to have given sufficient warning to the UK's public health experts.17 This should have triggered a ramping-up of data collection and general preparations for an unprecedented health emergency. The UK also had a small advantage over other European countries – a few weeks’ lag in the spread of the virus, in which to learn from ongoing crises close at hand. How much learning did take place within the key data-generating institutions will be a matter for the future inquiry. But self-evidently, epidemiological models need good databases, and if the pandemic had become a high-priority issue, experts would have begun concerted work. However, it is not clear that the surveillance system established by PHE and the NHS in late January was ever fit for purpose, which is surprising given the UK's well-established sentinel and other clinical surveillance systems for influenza.18

Given the obvious limitations of the initial PHE/NHS effort,19 it is all the more concerning that it was not until mid April that the ONS was tasked, with its research partners, to run a pilot COVID-19 Infection Survey.20 In order to predict how infection rates will change under certain scenarios, epidemiological models need to make assumptions about human behaviours. Devising methods of monitoring behavioural responses to the pandemic should have been a further early task for public officials, to give a better picture of the spread of the virus and help in the design of public health guidance and policy.

Only with evidence presented to a future inquiry will we learn whether, and to what extent, such work was being undertaken by PHE, the NHS and other key public institutions. Anecdotally, it was at the end of January that NHS England declared the virus a ‘level 4 critical incident’, and the first orders of personal protective equipment (PPE) were made. This then raises the question as to whether the warnings were taken seriously by policymakers, including government ministers, and what actions were taken in consequence.

Our initial review of the work undertaken in these early stages suggests that a lot of evidence about the pandemic was being generated by researchers based in universities, rather than at the key governmental institutions. Much attention has been focused on the model published by Imperial College London researchers (including Professor Neil Ferguson) on 16 March, which predicted that, without measures to suppress the virus, the pandemic could cause up to 510,000 deaths in the UK.

That model and the accompanying report21 are widely thought to have led to a major shift in government strategy, although it took a further six days for Boris Johnson to announce a full national lockdown. Yet there had been similar expert predictions close to government weeks before that. Professor Peter Openshaw, a member of the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (NERVTAG), a key government advisory committee, was advising from mid February that up to 60 per cent of the world's population could become infected and 400,000 people in the UK could die if no action were taken. Professor John Edmunds, a member of NERVTAG as well as of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M), warned on 26 February of 27 million infections and 380,000 deaths in the UK if no suppression measures were taken.

It is less clear that there was collaboration between institutions to monitor the spread of the virus and increase preparedness for widespread transmission. This may have been because key decision-makers were in denial about the seriousness of the threat, drawing on the previous experiences of SARS-CoV (2003) and H1N1 (2009–10) to support the belief that the new coronavirus would have low community transmission in the UK. As new evidence presented itself, cognitive dissonance may have impeded rational strategic adjustments.22

However, broader questions must be asked about the state of preparedness and capacity within the system, and particularly the health and social care sectors. Before the crisis, NHS England was missing all routine performance targets for access to care. Across the four nations of the UK, the NHS is poorly resourced compared with health services in other rich economies, in terms of both staffing and physical equipment.23 Adult social care has been a long-term weak point due to lack of integration in the wider health system and ineffective oversight from government.24 While before the pandemic the health services had been stockpiling to prepare for a possible no-deal exit from the European Union, the supplies were soon run down and the ‘just-in-time’ delivery system collapsed under the massive supply/demand shock.25 The crisis in PPE procurement was a particularly stark example of this.26

To be sure, readying any national health system for an emergency on this scale will always be challenging, and trade-offs must be made in the allocation of resources. Yet some early evidence suggests that problems of institutional expertise and capacity were at least partly responsible for the protracted crisis in PPE procurement.27

Public bodies defaulted to the playbook for mitigating pandemic flu, but COVID-19 differs in some crucial ways, and the strategy failed to adapt quickly enough when this became clear.28 Instead of strategic adaptation and execution – including incorporating the implications of emerging scientific modelling and learning from the pandemic response in other countries – efforts were (perhaps understandably) directed towards firefighting the problems associated with weak capacity. Future work should investigate whether the UK entered the crisis poorly prepared more on account of pre-existing institutional weaknesses in the health sector (for example, low hospital bed numbers) or more because decision-makers failed to heed the warning signs and empower the right people to take the necessary measures.

Either way, the ineffective joining-up of different data as part of a wider national pandemic strategy is well illustrated through study of failures in the test-and-trace system. A highly effective test, trace and isolate (TTI) programme, as other countries such as Singapore and South Korea have shown, is the only path to suppressing the virus without long-term intrusive lockdowns and physical distancing measures, or a vaccine. There may be a legitimate argument that the UK's testing systems were not ready, although questions must be asked about precisely why this was an area of such weakness and why the government did not take up offers of assistance from private laboratories that could have helped ramp up testing capacity earlier.29 If officials assessed that a widespread testing programme was too resource-intensive, why then were initiatives such as the ONS COVID-19 Infection Survey – or, initially, more targeted sampling – not begun earlier?30

These failures soon led to a woeful lack of data about the spread of the virus through the country, and made the rationale for a stringent national lockdown in March much stronger. Without an accurate idea of the virus's spread, it was also incredibly difficult for modellers to predict what the effect of different lockdown-easing measures would be.31 The effects of this poor data coverage continue to be felt today: we lack crucial information on how infection rates in the second wave compare with those in the first. The UK still does not possess a ‘world-beating’ testing system. Why this vital component of the pandemic response ground to a halt so quickly, and for quite so long, is a crucial question to be answered.

So too is the matter of why a tracing strategy was effectively abandoned. The government continues to deny that it did totally abandon its tracing effort. However, minutes from a Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) meeting on 18 February 2020 record discussion that PHE could only cope with tracing five new cases a week, with increased maximum capacity of only 50 new cases a week.32

Many public health researchers are on record saying that the UK abandoned its tracing strategy far too early. It is indeed quite extraordinary that tracing, which requires a relatively low-tech set of measures, should have been stopped so soon and so fully. At this stage, it seems that tracing was also not made a priority until April, which is disconcerting because there were gains to be had from a programme with limited coverage.

The government appears to have had a default preference for centralised programming, but effective tracing systems in other countries have typically involved localised systems which report to national institutions. What explains this seeming bias? Were these ‘political’ or ‘expert’ decisions? On what basis were the benefits of a more limited but targeted programme cast aside?

These are complex questions which demand detailed evidence-gathering and analysis, more usefully for future preparedness than for the apportionment of blame. Decisions about what is required for future preparedness will depend on whether the UK's problems stem more from over-centralisation, under-capacity and/or other factors. Taking the decision to lock down in late March as the critical juncture to be examined, it seems to be the case that failures in early evidence collection further narrowed an already constrained policy choice set and made a high-stringency lockdown almost inevitable.

IV. Structures and processes

We have argued that the UK, despite its strong scientific institutions, appears to have entered the crisis with a weak evidence base. Of course, that is not to say useful data (for example, some of the early modelling) did not exist at all, but rather that it was not necessarily being used in the right ways by the right institutions at the right times. In short, the government may have been operating without the right structures and processes in place in order for it to handle a lot of information efficiently and make effective decisions using it.

From March onwards, a lot of media attention was focused on the make-up of SAGE and the advice it gave ministers. This body of scientific advisers attracted a high level of public attention, particularly around its composition, which was not made public until a document was leaked to the media in late April. This created an aura of secrecy around who was advising ministers and how they were using that information. After the leak, attention was focused on the fact that the Prime Minister's adviser Dominic Cummings was attending meetings. A more important question, not being asked, was whether the right mix of scientists was represented on SAGE.

It was at first dominated by medical professionals.33 The crisis that medical scientists have prepared for most diligently is pandemic flu. It is therefore not surprising that early SAGE advice turned to the established procedures for responding to this type of crisis.34 As the minutes that were later published show, this flu playbook was drawn on heavily by SAGE members in the advice they gave to government, until perhaps the final days of February.35 Even on 10 March, the group still rejected (with no recorded dissensions) the option of a China-style lockdown.36

Avoiding a long and stringent national lockdown may have been viable if SAGE, its various subcommittees, the health institutions which some of its members led, and the government were working to maximise the effectiveness of alternative suppression measures. This would have required learning from other countries, such as South Korea, where widespread testing and tracing, alongside isolation and containment strategies, were effective alternatives to the severe lockdowns seen in many other high-income countries.37 Learning by example may have also brought forward a pivot away from the influenza-type strategy and led to more substantial incorporation of insights from the social sciences – particularly economics and behavioural science.

For example, a test-and-trace system can be highly effective, but only if there are also very well-designed incentives and systems in place to make sure that people isolate when asked to do so. Instead, many SAGE members seem to have held the prior that changing people's behaviours would not be possible at a scale that would substantially reduce the spread of the virus – leading to early high-intervention policies being discounted.38

It should not be expected that medical experts are also experts in the study of human behaviour; but what was needed to make up for these deficiencies was greater diversity of thought. The UK ended up losing out on the benefits of an earlier, ‘smarter’ lockdown, but by the time transmission was increasing exponentially it then also lacked the systems that would make less economically and socially costly measures viable. To work, these systems would have required building preparedness from late January at the speed and scale of a country on war footing. SAGE is not an operational body, and so it was not itself responsible for the apparently weak efforts here. But the basis of its advice should have pivoted from the influenza playbook sooner, and its members – many of whom do lead key operational bodies – could have levelled with government earlier about the different policy options available and the urgency of pursuing a clear strategy.39

Aside from the moments when studies developed in universities drove government policy, this advice from SAGE was presumably the key scientific evidence guiding the government's COVID-19 response strategy. It will be the task of a future inquiry to understand exactly how this advice was incorporated into government policy. Without doubt, policy should never be made on the basis of one, particularised, form of scientific knowledge. It is incumbent upon government ministers and their advisers to set up processes so that they are able to weigh up different forms of expertise. It will be important to ask whether structures were in place to balance SAGE advice with other evidence, such as economic and ‘within-health’ spillovers of the lockdown strategy.

An inquiry will be able to examine the nature of the committee structure ‘above’ SAGE, involving key decision-makers, and the extent to which they weighed its evidence against that provided by others. Only time and a thorough ex post look at the evidence will tell. At this stage, there are several initial indications that structures allowing for a critical distance between SAGE advice and policy decision-making were insufficient. One of these is institutional and drawn from Gus O'Donnell's professional experience in government. COBR meetings, which take place in the Cabinet Office Briefing Rooms (COBR), are standardly used in the UK to deal with short-term critical incidents. COBR, of which SAGE is a subcommittee, is often chaired by the Prime Minister, with other key ministers in attendance, as well as the heads of devolved administrations and relevant government agencies or bodies, as appropriate. COBR meetings are often highly effective in short-term crises.

However, COBR continued to be convened well into May, by which time various implicit political tensions had become apparent – for example, concerning the powers of city mayors and the heads of the devolved administrations. These meetings came to an end abruptly, perhaps partly because of these growing tensions. In any case, ad hoc committees are unlikely to be capable of developing and delivering a coherent strategy and policy output. They are likely to lack institutional ‘memory’, an issue that becomes more problematic if their composition is in flux. Typically, COBR meetings are thus more tactical and useful for immediate incidents than for long-term ones requiring more strategic thinking. The government may have realised this by mid May, but this was too late to change the trajectory of the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK.

As a point of contrast, it is worth understanding how government responds to other issues that, like COVID, are often crisis-driven, but operate with longer time horizons, require more strategic thinking and necessarily involve the heads of numerous departments. The National Security Council (NSC) is one such structure. Introduced by the coalition government in 2010, the NSC involves senior experts and officials explaining the nature of a security challenge, their reasoning as to what decisions are required, and their evidence base. Politicians then cross-examine the other members to test the evidence and recommendations. Then politicians debate the issues, which allows the non-elected members to understand political factors that have influenced their final decisions.

At the time of writing, the government has two key committees to deal with the COVID-19 crisis: one to look at strategy, chaired by the Prime Minister, and one to ensure implementation of that strategy, chaired by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office Michael Gove. The format now looks rather more similar to the NSC. COBR meetings, in contrast, are convened only when certain criteria are met, which generally involves a political calculation on the seriousness of an emerging threat and the advice of more junior committees. Again, it is key to understand the role of COBR in the early stages of the pandemic, the way it incorporated evidence and advice from different bodies, why it was deemed the most appropriate forum for strategic decision-making, and whether weak institutionalisation may have compromised the UK's early missteps. This will be a vital step to consideration of whether alternative structures may be more appropriate for dealing with crises that occur in the future.

One approach to understanding the impact of different advice presented to government is to measure how it weighed up the costs and benefits of certain policy actions. The quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) metric is a tool which has been used by the NHS for some 20 years.40 QALYs are used to inform most aspects of health policy. It would be possible to draw on this tool to measure the value the UK government put on one life saved from COVID. The flipside is to ask how much value the government put on saving the lives of those who died of non-COVID-related illnesses during the pandemic period, which could be estimated using the data on the UK's excess death rates (discussed in Section II) as well as modelling presented to the government on estimated deaths under different scenarios of lockdown.

There have also been high economic costs to people's lives as a result of shutting down the economy and schools, as well as social costs associated with loneliness and various other mental health effects of a long and severe lockdown. Research suggests that lockdown decisions imply a much higher value being placed on COVID-related deaths than the valuations normally used in government cost–benefit analysis, which have recently been reaffirmed in the latest version of HM Treasury's Green Book.41

Politicians have an understandable desire to avoid the kind of crisis in which people die due to lack of critical care capacity. However, this should not override the need to undertake cost–benefit analyses in order that informed decisions are reached using an agreed-upon framework. More recently, the government has been pressured into releasing such analyses, but, at least in their published form, they remain preliminary.42 This suggests that there were even less complete assessments for policy decision-making during the early stages of the pandemic. Without that holistic assessment, over time it becomes increasingly difficult for politicians to explain consistently the rationale behind decisions they make, and in turn for society to understand and respect that reasoning.

Policymakers have, of course, been operating under high levels of uncertainty, in part due to the vast gaps in data about the virus and transmission rates (discussed in Section III). In other work, one of the present authors (O'Donnell) has advocated for a quantitative measure of well-being years (WELLBYs) gained or lost under certain policy scenarios.43 While quite novel, this kind of common currency can allow policymakers to assess inevitable trade-offs. Meanwhile, SAGE expertise does not take into account variables, such as economic impacts, that a WELLBYs approach would incorporate, which is a slant reflected not just in SAGE's composition but also in the presentation of (publicly available) evidence it puts before government.44

There have been insufficient efforts to undertake cost–benefit analyses of lockdown and other COVID-related policies. The mistake is to believe that these cost–benefit exercises become policy prisons from which there is no escape. This is far from true: the point is that such major decisions require presentation of all available evidence, not just a particularised form of it.

V. Political leadership

Some initial studies offer preliminary suggestions, of more or less credibility, about the relationship between national political factors and pandemic outcomes. For example, Garikipati and Kambhampati (2020) show that countries led by women have had less severe experiences of the pandemic, and argue that this can be explained by more proactive early policy responses. Kavakli (undated) shows that populist and economically right-wing governments have reacted more slowly than others in implementing policies to mitigate the pandemic.

Dynamics of political leadership are important and should be considered because in the UK system it is typically elected politicians who are charged with making key policy decisions after evidence has been generated and presented to them. We identify three areas of investigation to establish the possible impact that political leadership has had on pandemic outcomes: communication, trust and length of tenure. These three aspects of political leadership show how untenable it is to rest on a claim that policy simply ‘follows the science’.

The task of political communication during a pandemic is particularly crucial because the public looks to national leaders for both information and inspiration. Political leaders are tasked with building a narrative that calibrates a suitable mix of both confidence and caution for the public. In the UK, politicians have typically led the announcement of policies and strategies, while government scientists have been charged with relaying information about the state of the pandemic in the UK. Scientists and politicians have often appeared alongside one another when addressing the public, most notably during the UK government press conferences that took place, at the height of the pandemic's first wave, almost daily between 16 March and 23 June. Politicians ideally present information to the public in a way that is easily understandable and which has particularly wide reach.

Choices about what information to include and how to present it may often be driven by political dynamics which come to have significant consequences. Some of these options were identified in Section II, such as which metrics government chooses to present information about mortality rates. There are also questions about what data are included or not in public information. It was only after 28 April that mortality figures presented to the public included deaths in care homes. Data on testing, meanwhile, were presented in a way which, to quote the head of the UK Statistics Authority, came ‘at the expense of understanding’.45

More recently, the Office for Statistics Regulation criticised the presentation of data used to justify England's second lockdown, stating that ‘the use of data has not consistently been supported by transparent information being provided in a timely manner. As a result, there is potential to confuse the public and undermine confidence in the statistics’.46 Data are generally chosen in strategic and often unhelpful ways – for example, a single national average of the R rate has typically been used in government presentations, which fails to convey significant regional variation. Government press briefings make scant attempt to balance representation of the pandemic's spread with data on the effect of different policy responses. How data are presented matters to the public and its ability to understand the rationale for government decision-making. But these choices can also come to affect how government and state institutions choose to allocate resources.47 If a politician sets an ambitious target, public resources will often be diverted to achieving that target, even if those resources might best be allocated elsewhere. Public communication not only matters for public trust in science, but can also have tangible effects on policy and thus the course of the pandemic.

As well as making decisions about the presentation of data, government also crafted campaign-style messaging that would build a public narrative focused on ‘beating’ the pandemic. The intent of these campaigns is also to guide, and where necessary change, behaviours.

From 23 March 2020, the government's public campaign focused around the message ‘stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’. Conformity to the lockdown was remarkably high, initially approved of by 93 per cent of the public,48 and the stringent set of policies even brought a spike in self-reported well-being. The causal mechanism is unclear, but it may be that people's well-being improves when given official ‘top-down’ guidance after a period of great uncertainty.49 However, it also seems plausible that the success of this campaign and its messaging may have been one reason why people who should have sought out medical help stayed at home.50 Moreover, the NHS may have been ‘protected’, as government ministers have been at pains to emphasise, but this was achieved by diverting resources from other health issues to COVID. The net impact of this is unclear, but the use of excess deaths and initial data on long-term health outcomes is at this stage a sensible interim measure.51

The clarity of the public messaging that people should minimise all forms of physical contact aligned with the strategy of a government whose primary aim was to reduce the COVID-19 death count, even where this may have had severe spillover impacts for other health as well as social and economic outcomes. After this initial campaign, from 10 May 2020, the UK government's communications strategy changed to ‘stay alert, control the virus, save lives’. This change was widely criticised by the devolved administrations and some parliamentarians for being ambiguous and unenforceable; ultimately, it was adopted only in England.

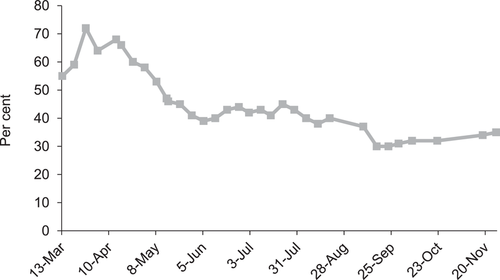

From this period on, the Westminster government has found it an increasingly difficult task to explain to people what the risks are and how this means they should be behaving. It is too early to reach any firm conclusions on what led public understanding (and approval) of lockdown policies to decline so precipitously. But the UK-wide polling about how well the government has handled the pandemic, shown in Figure 3, charts this precipitous fall in approval, beginning in mid April.

Percentage of people who think the UK government is handling the issue of coronavirus ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ well

Source: YouGov, ‘COVID-19 government handling and confidence in health authorities’, accessed 2 December 2020, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/international/articles-reports/2020/03/17/perception-government-handling-covid-19.

In England, the shift between the first and second public campaigns was a key transition moment. It illustrates the high stakes involved in public communication, and especially how difficult it can be to calibrate messaging when the task is to reopen a country.52 Evidence from the US suggests that compliance to physical distancing is initially responsive to the severity of the outbreak, but that this relationship weakens over time.53 One implication is that it may be more effective to design campaigns aiming for higher medium-term compliance, which would likely require a different set of interventions than for an initial stringent lockdown. However, limited thought appears to have been given to how to transition from a campaign that was optimised for a fear factor to one relying on higher individual discretion.

A successful public campaign to support a lockdown – or less stringent measures such as physical distancing – also requires that people understand why they are being asked to compromise their liberties and that they know the rules are being applied fairly and consistently. The more stringent the lockdown measures, the more that public perceptions about the fairness and appropriateness of those measures matter. There have been examples in many countries of senior officials contravening the tough rules that they had themselves put in place. For example, soon after its first lockdown was announced, Scotland's Chief Medical Officer resigned, after admitting that she had made trips to her second home. New Zealand's health minister was first demoted and later offered his resignation after repeatedly breaking lockdown rules. Public officials are held to higher account for their presumed knowledge of and adherence to COVID-related rules.

In England, soon after the transition to the ‘stay alert’ strategy, a story broke in several British newspapers about Dominic Cummings, the Prime Minister's Chief Adviser, breaking lockdown rules by travelling 420 kilometres with his wife (who had suspected COVID-19) and his child to his parents’ house in County Durham. One study offers preliminary evidence that this event led to a precipitous fall in confidence in England in the UK government (but, significantly, not in the other nations of the UK about their devolved governments).54 The event also coincided with significant drops in rates of conformity and understanding of lockdown policies.55 Ultimately, it will likely never be possible to fully disaggregate a cause-and-effect process of what led to this breakdown in popular support, given the proximity in timing of the Cummings scandal and the shift in UK government strategy for England. But research on trust and compliance to public health measures suggests it is not unreasonable to conclude that the Cummings scandal jeopardised the UK government's post-lockdown strategy.56 These events are a clear indication of the role that optics – and particularly perceptions of fairness and legitimacy – play in the success of government policy.

The Scottish government's track record since the pandemic further demonstrates this point. The severity of the pandemic in Scotland, as measured by excess deaths, is similar to that of England.57 Nonetheless, since April, confidence in the Scottish government has been far higher in Scotland than confidence in the Westminster government has been in England and, unlike the precipitous falls seen in England after the lockdown was eased, approval ratings in Scotland have only increased.58 These data are replicated in approval ratings for Scottish First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, who has enjoyed higher approval ratings than Boris Johnson in Scotland.59 During the initial lockdown phase, reported understanding of guidelines by adults across the UK was very high. Yet after these diverged across the UK nations, Scottish adults have consistently reported higher levels of understanding of the rules than have English adults. In July, fewer than half of people in England reported that they understood the rules (with 14 per cent ‘very much so’), whereas in Scotland three-quarters reported understanding (with 27 per cent ‘very much so)’.60 Throughout the pandemic, more people in Scotland and Wales have reported complete compliance with lockdown rules than in England.61

Modelling the effect of this on pandemic outcomes would be difficult given demographic and other differences between the UK nations. It is clear that the Scottish First Minister has been far more successful in delivering a public relations campaign than has the British Prime Minister. This matters not only for politicians and their ambitions at the polls, but also for the country's ability to suppress the pandemic. Research shows that trust in government is positively correlated with adherence to lockdown measures.62 Confidence in government is also positively correlated with life satisfaction; and life satisfaction with conformity to lockdown rules.63 We cannot say how England would have fared in a world where the UK government had handled these dynamics better, but this research suggests that the government's job has been made only harder with the erosion of trust.

Indeed, governments must be especially cautious about how their decisions affect public trust and well-being. Actions that weaken them may undermine the potential for public policy to have its desired impacts (suppressing the R rate; stimulating the economy). COVID-19 can ultimately only be contained by changing people's behaviours, or a vaccine. Without the latter, political action that jeopardises state capacity to change behaviours can be costly. In that sense, had it drawn more substantively on evidence from the social sciences, the government might have better appreciated the value of political communication to bolstering the efficacy of policies designed to minimise virus transmission.

A final point to note is that Boris Johnson's Cabinet went into this crisis with comparatively limited experience in positions of power. At the start of the pandemic, Cabinet members had an average of just 19 months of Cabinet-level experience. Fourteen of the 22-strong team had been in Cabinet for less than a year, and only one – Michael Gove – was a veteran of David Cameron's 2010 Cabinet. Representation of veterans in Cabinets has generally weakened in recent decades.64 There have, of course, also been three general elections in the course of four-and-a-half years, as well as significant churn among the top positions in the civil service.

A recent Institute for Government report points out that ministers with less than a year's experience have generally not had the opportunity to take part in live planning exercises or build relationships with stakeholders beyond their department.65 This, the report argues, may explain why the government did not use established communication structures – for example, by regularly briefing the public on policy decisions with major implications for the health service without giving notice to NHS leaders. Frustration with government consultation and communication processes ultimately led the senior leadership of NHS Providers, which represents NHS Trusts, to write to Matt Hancock to request that government adhere to established protocol.66

Cumulative ministerial experience is clearly no panacea for lack of government capability, but it is undeniable that there has been a period of comparative instability in the top ranks of the UK government since David Cameron's resignation after the 2016 EU referendum. The impact of this inexperience would be impossible to measure, but recognising this as a potential point of vulnerability may open up pathways to reform that mitigates the impact of political inexperience.

VI. Economic policy

A further aspect of political leadership relates to the distributional consequences of decisions that politicians make. 2020 has seen the most significant interventions by the state in the economy since the Second World War. By May, UK government debt had exceeded the size of the national economy for the first time since 1963. The decision for a second England-wide lockdown brought a further economic shock, leading the Chancellor to announce an extension of the flagship Coronavirus Job Retention, or ‘furlough’, scheme until March 2021. By November, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimated that the deficit for 2020–21 would peak at between £353 billion (upside scenario) and £440 billion (downside scenario).67

The sheer scale of economic support measures being undertaken across the world means that a very large public debt burden will be a fixture of advanced economies for a long time to come. Significant tax rises are a close-to-inevitable consequence of this. Injecting these vast sums of money into the economy inevitably has distributional effects. A now significant literature shows that the multiple rounds of quantitative easing (QE) used after the 2008 global financial crisis by the central banks of high-income countries brought greater gains for asset owners than it did for workers. QE is being used again in 2020; however, it is being combined with a variety of additional economic support measures for workers, such as the furlough scheme, which in its first iteration supported 9.6 million jobs.68 Without doubt, this scheme has been invaluable for supporting workers and keeping firms viable during the first lockdown; it will continue to play that vital role in 2020 Q4 and 2021 Q1.

Nonetheless, the furlough scheme's effects have been complex, and initial research has shown some of the distributional effects, which could possibly have been mitigated had certain design features been different.69 For example, workers on higher incomes, and men (unconditionally) are more likely to have received discretionary additional payments (‘top-ups’) from their employers.70 On the flipside, women are more likely to have initiated dialogue with their employers about being furloughed, an outcome seemingly driven by women who have children at home (and, correspondingly, much less by men who have children at home). This fits with data showing that women took on more childcare and housework responsibilities, and less paid work (by hours), during lockdown.71 The rate of furlough was much higher among those under the age of 35 and among workers with varying hours (rather than fixed-term contracts). As a group, and as might be expected, furloughed workers were much more likely to fear that they would lose their jobs before August than non-furloughed workers.72

The furlough and other components of the government's economic support package have widely been hailed as successful interventions. Without doubt, the scheme has saved many jobs and, by extension, many millions of livelihoods. Equally, there have been some areas of deficiency. For example, the Self-Employed Income Support Scheme has been poorly designed, with research showing that some whose incomes were not affected have benefited, while some in critical need of support received limited or no payment.73

Evaluating these support schemes is inseparable from understanding how some of the key decisions taken by government, such as closing schools and nurseries, may have exacerbated distributional effects.74 For example, there are likely to be compounding negative effects of the pandemic for the UK's ethnic minorities, who are more at risk to losses in income and (among the young) whose education and long-term life impacts are likely more impeded by school closures, for various reasons.75 As we have been at pains to stress, ‘following the science’ does not lead to inevitable policy decisions, but always involves making decisions about various social and economic trade-offs.

In the case of the decision to close schools and keep them shut, it is probably true that this reduced the R rate, but equally it is essential to see the myriad feedback effects of that decision, including suboptimal distributional outcomes for structurally disadvantaged groups such as women, young people and ethnic minorities.76 Prolonged school closures were also probably influenced by the tenor of the government's lockdown campaign: parents, pupils and teachers were, like the rest of the population, responsive to messaging that induced fear about any physical contact. Research published in May showed that fewer than half of parents would send their child back to school if they had the choice, with lower-income parents being even less willing to do so.77 Political decision-making – for example, around the fear factor stimulated via the public campaign – is part of a lengthy causal chain which may unwittingly result in the further widening of socio-economic disparities.

We acknowledge that in the highly activist policy environment such as we have seen since March 2020, most decisions required working on limited established precedent and under high uncertainty. But this environment made the need for a framework for policymakers to evaluate the myriad trade-offs of policy decisions even more important. It is difficult to see how decisions taking full and proper account of the various costs and benefits were possible without sustained input from social scientists. The economic recovery from the pandemic will require policies that give higher distributional weighting to minority groups whose livelihoods have been especially affected by the pandemic.78 It would have been far better had these increased disparities in livelihood been mitigated in the first place.

VII. Institutions

Institutions, according to a classic definition, are ‘the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’.79 The foregoing sections have dealt implicitly with some issues related to how institutions have performed in the UK during the COVID-19 crisis – for example, how COBR has been used as a decision-making forum for politicians to decide emergency policy measures. Data pass through institutions such as COBR and are used by politicians to decide on which policy outputs are appropriate given the available evidence and various uncertainties. Other institutions are then tasked with implementing these policy decisions, as part of their broader remit to achieve particular outcomes, whether that be protecting public health in the case of Public Health England or educating the population for the Department for Education.

These institutions’ ability to fulfil government and department-specific policy goals depends on various factors, such as the quality and appropriateness of the policy prescribed by central government, the requisite skill and talent base within the institution and its ability to collaborate effectively with other relevant parts of government and society. This section investigates some features of the UK's institutional mix that may have compromised its ability to respond effectively to the public health challenges brought by COVID-19.

On the one hand, it may be the case that the design of some of the UK's institutions and how they interact with one another mean that the deck was stacked against the many competent public officials tasked with responding to the pandemic and mitigating its worst effects. In Section IV, we outlined some of the issues with using COBR as the main government body for emergency policy response. Broadening this assessment, one of the major challenges for policymakers has been responding to issues that require deep and sustained collaboration across the entire government machinery. There are what might be considered the ‘core’ institutions of the Department of Health and Social Care, Public Health England, NHS England and their counterparts in the devolved governments. In addition, coordination has been essential between central government, the devolved administrations and local government. Other key institutions include the Care Quality Commission, the Department for Education, the Home Office, HM Prison Service and their devolved counterparts, as well as those for UK-wide travel and border control, such as the Civil Aviation Authority and Border Force. Within these various bodies, there have also been subdivisions charged with discrete responsibilities, such as the NHS's newly formed unit for technology, NHSX.

This abbreviated list shows the vast array of institutions that need to work together within a wider network, engaging on cross-cutting challenges. In government, inter-institutional collaboration is a strategic and communicative challenge in normal times. It may be that the challenges presented during COVID-19 have exposed the UK's institutional make-up as inadequate for achieving good outcomes.

There are several indications that this argument may have some merit. We focus on the major institutional shifts that have occurred since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis as evidence of subpar institutional arrangements for delivering on policy. There have been three major institutional shifts in the UK (and more specifically England) since the crisis: the establishment of NHS Test and Trace (NTT), the development of the NHS COVID-19 app by NHSX and more latterly NTT, and the abolition of PHE. The establishment of NTT was announced by Health Secretary Matt Hancock on 23 April 2020. As has been identified, the test-and-trace strategy taking so long to come to fruition may be an indication that PHE was poorly prepared for a pandemic, despite the development of such a strategy being fully within its mandate.80

That a new and separate body in NTT was necessary shows PHE's institutional weakness; that it arrived so late suggests weak oversight and accountability – and a lack of strategic forethought – by politicians and other public officials. Relatedly, it was NHSX and not PHE or NTT that had been given initial responsibility for the development of a phone app that would alert users if they had been in physical proximity to someone who later tested positive with COVID. The first months of the app's development were mired in delay and what appear to be some serious missteps by NHSX, such as around whether the app should follow a centralised or decentralised model of data management. The Health Secretary's transfer of responsibility for the app from NHSX to NTT shows political powers of delegation at work, but also raises questions about political influence over science policy. Where did the idea that this technological innovation would ever be a ‘silver bullet’ come from? Political oversight is a requirement of any democratic system, but situations in which politicians can give misleading impressions about the potential for a scientific or technological innovation to deliver are demonstrably unhelpful. These powers can have a real impact on outcomes, and must be subject to rigorous checks and balances. More generally, one lesson here is that the UK – and in fact the global community – is some way off being able to harness technology effectively in emergency situations.

A case in point of weak performance paired with high political interventionism is PHE and the decision to abolish it. PHE on paper would seem to have been the most obvious place for a testing system to be instituted and a tracing app to be developed, but it has fared especially poorly throughout the pandemic, to the extent that in August 2020 government announced that it would be replaced by a four-nation National Institute for Health Protection (NIHP). It would be premature to level blame directly at PHE for its record. PHE was established as recently as 2013, as part of the Lansley reforms. Questions must be asked about how such a young executive agency – supposedly designed to respond to the cross-cutting challenges of public health in the 21st century – came to be such a weak point for government delivery. For the future NIHP, it will be vital to have a thorough consultation process involving both medics and public management experts to decide what its mandate should be, including the extent and form of its relationship with the public. For example, PHE had a pronounced public-facing role to improve the nation's health and well-being. However, perhaps partly because of this responsibility, it does not seem to have enjoyed public trust or respect, unlike similar institutions in other countries. There must be concerted thought given to what kind of institutional relationship the NIHP has with elected government as well as the public. More formalised checks and balances that insulate it from short-termist political machinations are likely required, as well as stakeholder engagement of the kind expected in a democracy.

An alternative approach would be to look less to the design of government institutions and more to the individuals who fill their ranks. The problem of attracting and retaining highly skilled people in the public sector varies depending on the department and profession in question, but there are systemic challenges. Years of wage restraint after the 2008 financial crisis mean that the difference between public and private sector hourly pay has fallen to below pre-crisis levels, with public sector earnings 2.5 per cent lower on average in 2019 than at the start of 2010.81 The last time the gap between public and private sector wages was so low was in the early 2000s, when there were major recruitment shortages in parts of the public sector.

We are concerned especially with the effect of differential wage rates in top positions, which are typically occupied by individuals commanding the highest salaries and who provide organisational leadership and strategy.82 Here, it really does pay to work in the private sector: research in 2014 showed that at the 99th percentile of the distribution, hourly pay was 20 per cent higher in the private than in the public sector.83 Inevitably, these differences will have left certain public sector skills gaps. Over time, this creates structural inefficiencies which ultimately affect the delivery of public services. For example, it has always been difficult to retain really good staff in procurement positions because these specialists are paid much more in the private than in the public sector. Therefore, it was not especially surprising that the NHS's procurement arm came under such strain during the early months of the crisis. Its weaknesses may in part explain why such high volumes of procurement work were soon outsourced by government, a process during which established procedures were abandoned and the risks of fraud and poor value for money increased substantially.84 Failure to invest in the public workforce during normal times can, when serious disruption occurs, lead to systems buckling.

Of course, the causes of poor institutional performance are likely to lie somewhere in between these two dimensions. A well-designed institution that attracts high esteem for its work will be able to attract and retain better staff over the long term. More skilled and motivated staff will operate with greater agility and, where appropriate, actively seek to improve outcomes through innovative collaborations with other parts of government. Conversely, where resources are low and institutions cannot innovate, talented individuals will soon move elsewhere. This can in turn weaken important cross-government collaboration. Cumulatively, an institution that has been just about coping may reveal its cracks when a crisis hits, and be unable to respond to novel challenges.

While the evidence is still somewhat preliminary, a particular area of weakness in government delivery – at least in England – during the COVID-19 crisis seems to have been the ability of central and local governments to collaborate. Part of this surely has to do with changes in local government funding since the financial crisis. In England, local government revenues fell by about 18 per cent in real terms between 2009–10 and 2019–20, or about 24 per cent per person.85 Local governments are also today far less reliant on central government grant funding than they have previously been, with a 77 per cent fall in revenues per person from this source over the same period. Employment in local government has also been on a downward trajectory since the financial crisis. All of this has likely had a detrimental effect on the ability of the two levels of government to cooperate effectively, especially around apparently ‘non-essential’ services. Emergency planning expenditure by local authorities in 2018–19 was 35 per cent lower in real terms than in 2009–10.86

Exercise Cygnus, a simulation run by government to practise responding to pandemic flu, identified particular deficiencies within local government concerning its ability to respond to challenges in the provision of social care, particularly if the NHS were forced to cancel a majority of appointments and procedures. While the Department of Health and Social Care has said that it addressed all of the recommendations made after Exercise Cygnus that related to the department itself, local authorities and social care providers have said that they were not involved in implementing recommendations.87 In any case, the COVID-19 crisis has revealed major deficiencies in social care and community health, as the Cygnus simulation predicted. Government has been forced to rely on limited accurate information about the state of care homes during the pandemic, such as rates of occupancy and the severity of outbreaks.88 Recent data show that only around a quarter of people who required access to community services in April 2020 actually received such care.89 It is difficult at present to understand the cumulative effect on health outcomes. But the number of deaths in care homes is one of the major reasons behind the UK's depressing record during COVID.90 It is difficult not to draw connections between the weakness of the social contract around adult social care in the UK and the ineffectual collaboration between central and local government. These conditions were conducive to the drawn-out tragedy faced in care homes across the country.

The UK central government has made considerable use of contracting out to private sector firms in order to respond to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. This reliance may itself stem from low interdependence and collaboration between the centre of government and its more ‘peripheral’ components. Contracting out is a model that has always been used by governments, but its use expanded dramatically in the UK during the 1980s with the introduction of compulsory competitive tendering, among other innovations. Such outsourcing, where firms compete for contracts, holds the promise of increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery. There is a long-standing debate on just how effective outsourcing has been for public services, and a recent trend towards ‘insourcing’ certain areas is observable.

We are continuing to learn more about how outsourcing has been used during the COVID-19 pandemic – for example, the National Audit Office's November 2020 investigation has thrown up some of the issues associated with government procurement during the pandemic, including poor audit trails, retrospective contracting and delayed publication of contracts.91 There needs to be broader investigation of whether reliance on contracting out in recent decades has reduced state capacity; and a systematic assessment of how private sector delivery has performed compared with public sector delivery during the pandemic.

It is unlikely that we will find straightforward answers to these investigations, and another dimension to consider is whether there have been benefits to programmes delivered more through centralised or decentralised and ‘networked’ systems. For example, there have been reports that offers from the country's leading scientific institutions and private laboratories to help with the testing system were ignored, perhaps because the government defaulted to the idea that new customised systems managed by private companies would be more efficient.92

These critiques are important, but ultimately only so useful. Mass testing was always going to be a challenge and it is impossible to answer the counterfactual of what would have happened under a system using more public sector provision. But what may be possible, and potentially much more useful, would be a cross-country comparison bringing more conclusive evidence as to whether and how the outsourcing model compromised state capacity. Each country has its own unique political economy and so we cannot expect ready-made solutions when learning from other states. Evidence so far suggests that countries such as Germany and South Korea were more successful in part because of how they leveraged local systems and expertise generally unobservable and underutilised by central government.

From such a comparative exercise, we might learn how to make British institutions better at adapting to new challenges at speed. If this requires insourcing areas of public sector delivery – even if that appears to erode some of the touted benefits of competition and efficiency – that might be a price worth paying. It would be a gear-change in the philosophy of public sector delivery as it has developed in the UK over the past 40 years. But it carries the potential for the UK to better harness some of the genuinely world-beating science resident in its borders. This might require investing much more heavily in sectors that appear quite far from the ‘real’ science, such as local government. Contained within such institutions is a rich knowledge about how people respond to novel challenges such as those being thrown up in this new decade. It is the many millions of choices made within communities that ultimately determine the course and impact of a pandemic, as a resurgence of work to map and regenerate civil society in the UK reflects.93

The journalist Gillian Tett argues in a forthcoming book that countries more successful in responding to the pandemic have been able to combine multiple forms of scientific expertise, drawing on disciplines ranging from the biosciences to anthropology. Institutional renewal in the UK should, to this extent, be about bringing greater alignment between where our excellence is currently found – at the frontiers of scientific discovery – and where it has been found wanting, within the institutions that must likewise be high-performing to deliver the benefits of scientific excellence to society at large. This process of renewal, we argue, requires wielding a different kind of expertise which we see as having been undervalued in the UK's response to COVID: methodologies and insights drawn from the social sciences.

VIII. Conclusion: the design of the public inquiry