Prevalence and risk factor assessment of Tropheryma whipplei in a rural community in Gabon: a community-based cross-sectional study

Abstract

Tropheryma whipplei is the causative agent of Whipple's disease and has been detected in stools of asymptomatic carriers. Colonization has been associated with precarious hygienic conditions. There is a lack of knowledge about the epidemiology and transmission characteristics on a population level, so the aim of this study was to determine the overall and age-specific prevalence of T. whipplei and to identify risk factors for colonization. This molecular epidemiological survey was designed as a cross-sectional study in a rural community in Central African Gabon and inhabitants of the entire community were invited to participate. Overall prevalence assessed by real-time PCR and sequencing was 19.6% (95% CI 16–23.2%, n = 91) in 465 stool samples provided by the study participants. Younger age groups showed a significantly higher prevalence of T. whipplei colonization ranging from 40.0% (95% CI 27.8–52.2) among the 0–4 year olds to 36.4% (95% CI 26.1–46.6) among children aged 5–10 years. Prevalence decreased in older age groups (p <0.001) from 12.6% (95% CI 5.8–19.4%; 11–20 years) to 9.7% (95% CI 5.7–13.6) among those older than 20. Risk factor analysis revealed young age, male sex, and number of people sharing a bed as factors associated with an increased risk for T. whipplei carriage. These results demonstrate that T. whipplei carriage is highly prevalent in this part of Africa. The high prevalence in early life and the analysis of risk factors suggest that transmission may peak during childhood facilitated through close person-to-person contacts.

Introduction

Tropheryma whipplei is the causative agent of Whipple's disease—a condition characterized by diarrhoea, weight loss and arthralgia 1-5. Extra-intestinal manifestations involving the heart and the nervous system have also been reported 6-10. However, T. whipplei has been frequently detected in stool samples of healthy volunteers without signs or symptoms of disease. These findings indicate that colonization is common and that only a minority of infected individuals ultimately develop Whipple's disease 11.

Prevalence of asymptomatic carriers—assessed in case series or focused investigations of high-risk populations—was reported as 4% of the adult population and up to 12% among sewer workers in France 12 and 25% in Austria 13. The high prevalence among sewer workers and people living in homeless shelters (12.9%) 14 was interpreted as evidence for transmission facilitated by poor hygienic conditions. Similarly, T. whipplei was detected in stool samples in 15% of children with gastroenteritis in a hospital in France as opposed to none in the healthy control group 15. This finding led the authors to speculate about the importance of a faecal–oral route of transmission among young children and the hypothesis of primary infections causing gastroenteritis.

Data from tropical regions are scarce and mainly reported from Senegal indicating a high prevalence of T. whipplei infection especially among young children 16-19. However, there is a lack of community-based data and investigations from other parts of Africa to provide additional information about the prevalence and potential risk factors for transmission. Community-based data are considered particularly important to further describe transmission characteristics since such studies allow for comparative evaluation of age groups, intra-familiar clustering and other potential epidemiological risk factors for T. whipplei infection.

The aim of this survey was therefore to determine the overall and age-specific prevalence of T. whipplei colonization on a population level in a rural community in Central African Gabon. Demographic characteristics about the participants and information on their households were assessed for analysis of potential risk factors for transmission of T. whipplei.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey assessed the prevalence of T. whipplei in stool samples of inhabitants from the small rural community Bindo near Lambaréné in the province Moyen Ogooue in Central African Gabon (Fig. 1). The study region is characterized as a rural region amid tropical rainforest with agriculture as the main occupational activity 20. Intestinal helminths and polyparasitism are highly prevalent due to suboptimal hygienic conditions 21. All members of the community were invited to participate in this survey irrespective of age or health status. A total of 507 inhabitants agreed to take part in the study after provision of written informed consent.

http://commons.wikimedia.org, adapted by the author

.Using a questionnaire-based interview, information about demographic characteristics of the participants (age, sex, nationality, occupation, religion, ethnicity) and their family relationships were obtained. All households were visited and information about the living conditions of the participants was recorded (number of persons living in household, number of persons sharing a bed, building material of house, presence of private toilet, electricity, or refrigerator, and sources of water).

Stool samples were collected from all participants, immediately conserved at 4°C and transferred to the Centre de Recherches Médicales de Lambaréné for storage at −80°C. All samples were shipped on dry ice to the Medical University of Vienna for further analysis. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) applying the protocol for isolation of DNA from stool for pathogen detection 22. Quality of DNA extraction and absence of inhibitors for PCR were checked by a PCR protocol targeting Helicobacter pylori and demonstrating a comparable prevalence as described in previous studies (data not shown) 22. Real-time PCR was performed on a LightCycler apparatus (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) following a previously published protocol 12, 23 employing the primer pair TW27F and TW182R and the Taqman probe 27F-182R. A clinical Tropheryma isolate obtained from a histologically confirmed Morbus Whipple patient served as positive control and was used alongside a negative control in all PCR assays. Samples were run in duplicate and were considered positive if at least one of the reactions was positive. In case of positivity, the amplicon was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and subjected to sequence analysis to confirm specificity of the result. Sequencing reactions were performed using the Big Dye Terminator kit v.1.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Excess of dye terminators was removed by Centri-Sep columns (Princeton Separations, Freehold, NJ, USA) before sequencing on a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All categorical values were compared employing chi-square tests. Odds ratios were calculated and a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate risk factors for transmission. An α value of 0.05 was chosen as the significance level. The study protocol was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Medical University of Vienna and the respective regional ethics committee in Gabon (Comité d'Ethique régional de Lambaréné).

Results

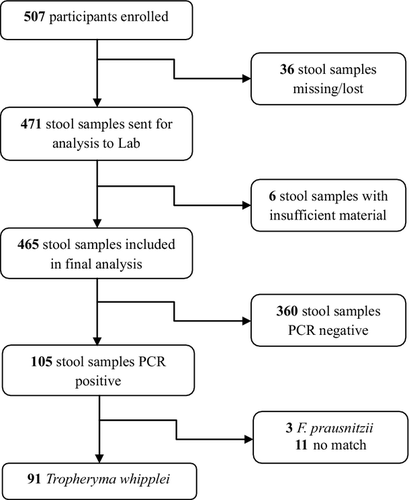

A total of 507 stool samples were collected from volunteers between September 2010 and March 2011. Loss of specimens (n = 36) and inadequate sampling (n = 6) led to the analysis of 465 of the 507 stool samples by real-time PCR for the presence of T. whipplei and 105 (22.6%) of these specimens yielded a positive result (Fig. 2). Amplicon sequencing of positive samples was performed and 91 of 105 (86.7%) samples were confirmed as T. whipplei. Among the remaining 14 samples, sequencing demonstrated Faecalibacterium prausnitzii—a commensal bacterium of the human gut flora—in three cases (2.9%) and no significant match for the remaining 11 (10.5%) samples, meaning that neither T. whipplei nor another bacterium corresponded to the result. In 12.4% (13/105) of the positive samples only one PCR was positive and the other remained negative. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that the load of T. whipplei might have been at the limit of detection—nine of these 13 samples were confirmed as T. whipplei by sequencing while four showed no significant match.

This resulted in an overall prevalence of 19.6% (95% CI 16–23.2%) for presence of T. whipplei in stool samples of the study population. To further characterize the age-specific prevalence of T. whipplei, the study population (mean age 24.7 ± 19.9 years) was divided into four age groups (Table 1). The younger age groups showed higher prevalence for T. whipplei with 40.0% (95% CI 27.8–52.2%) among the 0- to 4-year-olds and 36.4% (95% CI 26.1–46.6%) among the children aged 5–10 years. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of T. whipplei between these two age groups. However, prevalence in the older age groups was significantly lower compared with the younger age groups (p <0.001) with 12.6% (95% CI 5.8–19.4%) among the 11- to 20-year-olds and 9.7% (95% CI 5.7–13.6%) in adults >20 years of age.

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean age | 24.7 (±19.9)a |

| Mean age female | 25.8 (±20.9)a |

| Mean age male | 23.4 (±18.8)a |

| Age group 0–4 years (%) | 65 (14) |

| Age group 5–10 years (%) | 88 (18.9) |

| Age group 11–20 years (%) | 95 (20.4) |

| Age group >20 years (%) | 217 (46.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 238 (51.2) |

| Male | 227 (48.8) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| Gabonese | 406 (87.3) |

| Others | 26 (5.6) |

| Not known | 33 (7.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Bapunu | 165 (35.5) |

| Fang | 91 (19.6) |

| Nzebi | 67 (14.4) |

| Massango | 29 (6.2) |

| Others | 68 (14.6) |

| Not known | 45 (9.7) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Christian | 336 (72.3) |

| Muslim | 10 (2.1) |

| Traditional | 18 (3.9) |

| None | 46 (9.9) |

| Not known | 55 (11.8) |

| Tropheryma whipplei carriage, n (%) | |

| All age groups | 91 (19.6) |

| 0–4 years old | 26 (40.0) |

| 5–10 years old | 32 (36.4) |

| 11–20 years | 12 (12.6) |

| >20 years old | 21 (9.7) |

- a Standard deviation.

Demographic characteristics of all participants were collected by questionnaire-based interviews (Table 1). Study participants' age ranged from 0 to 80 years and men and women were equally represented in the population sample (48.8% and 51.2%, respectively). The prevalence of T. whipplei was higher among men (23.3%; 95% CI 17.8–28.9%) than among women (16%; 95% CI 11.3–20.7%; p 0.05).

A total of 117 households participated in this study with a mean of 4 (±2.8) persons per household. No case of T. whipplei was recorded in 69 (59%) households and in 48 (41%) at least one case of T. whipplei was observed. Households with T. whipplei carriers were located randomly across the entire village. Household characteristics were analysed for risk factors associated with T. whipplei colonization. No association was found between households with or without T. whipplei carriers and factors including type of housing (wooden or concrete building) as well as the presence of a toilet, electricity, a refrigerator or the usage of different water sources (river, public well and rainwater; data not shown).

Participants' risk factors were assessed in univariate analysis indicating age, sex and number of people sharing a bed as significant risk factors for T. whipplei (Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that increasing age was associated with reduced risk for T. whipplei with an odds ratio of 0.96/year (95% CI 0.94–0.97), while male sex had an odds ratio of 1.64 (95% CI 1.01–2.67) and was therefore associated with a higher risk of T. whipplei. The number of people sharing a bed was associated with infection by an odds ratio of 1.21 (95% CI 0.97–1.51) in multivariate analysis.

| Risk factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.94–0.97 | 0.96 | 0.94–0.97 |

| Age >10 years | 0.19 | 0.12–0.31 | a | a |

| Sex (male) | 1.62 | 1.02–2.59 | 1.64 | 1.01–2.67 |

| Persons sharing bed | 1.33 | 1.07–1.65 | 1.21 | 0.97–1.51 |

| Persons sharing household | 1.09 | 1.02–1.17 | a | a |

| House type | 1.05 | 0.64–1.74 | a | a |

| Toilet | 1.04 | 0.58–1.85 | a | a |

| Electricity | 1.60 | 0.73–3.51 | a | a |

| Fridge | 1.36 | 0.85–2.20 | a | a |

- a Not included in multivariate logistic regression model.

Discussion

This study is one of the first attempting a molecular epidemiological survey to investigate the prevalence of T. whipplei on a community level in Africa. The high prevalence of 19.6% T. whipplei carriers among the asymptomatic general population of a rural village in Gabon is in line with previous results where the prevalence was 31.2% in two villages in rural Senegal 18. Age-specific analysis revealed a high prevalence of carriage in children between 0–4 years (40%) and 5–10 years of age (36.4%), but significantly lower carriage rates in older children and young adults between 11 and 20 years of age (12.6%). Our data show comparatively lower rates of T. whipplei carriage in Gabon compared with the Senegalese study reporting up to 75% prevalence in children below the age of 5 years. Interestingly, the prevalence in the adult population (9.7%) was comparable to data from high-income countries including France where the prevalence in case series was reported to be between 4% in the general adult population and 12% in the high-risk population of sewer workers 12. Finally, the comparatively higher prevalence of T. whipplei among children indicates that colonization may not persist for life and that maintenance of colonization in adulthood potentially necessitates repeated re-infections. However, the alternative explanation of this finding may be the long-term carriage of T. whipplei in certain individuals. Future prospective studies are needed to address this epidemiological question.

Whereas our data confirm a higher risk of colonization with T. whipplei in children, our data also show an association between male sex and colonization. Whether this may be a result of increased exposure or higher susceptibility in our study population remains to be further investigated.

The absence of associations between household characteristics including sanitation and T. whipplei carriage is in contrast to previous reports 19. Although intuitively convincing, we speculate that socio-economic differences were only minor in our study population and potential differences were further diluted by close social contacts between families. However, our data are supportive of a proposed person-to-person transmission, presumably favoured under poor sanitary conditions, as indicated by an association between number of persons sharing a bed and presence of T. whipplei. As a higher number of persons per bed was most often the result of multiple children sleeping in the same bed and as children are the most important risk group, this finding is in line with the overall epidemiological understanding of T. whipplei infection.

The hypothesis of human-to-human transmission, most likely through a faecal–oral or oral–oral route, has also been proposed by a study conducted in France, where family members of patients with Whipple's disease and of asymptomatic carriers were screened for T. whipplei. The family members had a higher prevalence of T. whipplei than the general population and in some families the same genotype was circulating, supporting the theory of intra-familial transmission of T. whipplei 24. In our study we did not use genotyping to further investigate the possibility of transmission between family members as we had no cultures of T. whipplei available to employ this method.

Our study did not assess the impact of diarrhoea on T. whipplei carriage in stool samples as reported previously 15. Persons with acute diarrhoea provided stool samples only after recovery and therefore our data do not add information about the potential of T. whipplei as a diarrhoeagenic pathogen.

Hence, our data demonstrate a high prevalence of T. whipplei among an asymptomatic population in rural Gabon and we conclude that asymptomatic T. whipplei carriage is very common in this part of Central Africa. The high prevalence among children suggests an increased risk for transmission during childhood with male sex and bed sharing constituting further risk factors associated with T. whipplei carriage.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the enthusiastic support by the Gabonese field workers and the support by the community health workers in Bindo. The participation by the community of Bindo is greatly appreciated.

Author Contributions

MR and AM designed and conducted the study, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; NH, TB, BH, HL, FL, GMN, CM, AAA and PGK contributed to study design, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge financial funding for this study provided by the Austrian National Bank Anniversary Fund (grant number 13685). The work had logistical support from the Global Infectious Disease Control Association.

Transparency Declaration

The authors report no competing interests.