THE MISSING PEOPLE OF STATE-SUBSIDIZED HOUSING: Lived Experiences of Non-Occupancy and Secondary Residential Mobility

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), project number 456455682. The study received complementary funding from the Ruhr University Bochum Research School PLUS, the TU Dortmund Young Academy and the CNRS Laboratoire Mosaïques LAVUE UMR 7218.

I express my gratitude to all the interlocutors and intermediaries in the field! I feel indebted to my research partners and translators, Sawssane Bourhil, Soufiane Chinig and his family, Melisa Dlamini, Seble Fekadu Deyaso, Houssine Lamaatchi, Ghizlane Orkhis, Ntombizawo Qina and Manon Troux, who made this research possible. Furthermore, I would like to thank the Centre for Urbanism and Built Environment Studies (CUBES), Johannesburg, as well as the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies (CFEE), Addis Ababa, for their institutional support. Finally, I am grateful to all members of the International Planning Studies (IPS) research group at TU Dortmund University, the Global-Tübingen Urbanities Research Network (G-Turn) and the CNRS Laboratoire PASSAGES UMR 5319 at the University of Bordeaux-Montaigne for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Abstract

Large-scale, state-subsidized housing programmes have experienced a renaissance in Africa, Asia and Latin America, but provoke justified concerns about whether they miss their target groups. Unaffordability, lack of choice, peripheral locations and under-serviced sites are common problems. Ultimately, many subsidized units are not occupied by their intended recipients. Most authors see this as a form of gentrification or downward-raiding, whereby higher income groups displace housing recipients towards poor-quality housing elsewhere. However, most research fails to include the perspectives of those who do not occupy or who vacate their units, mainly because of the methodological challenges of locating these people. Consequently, little information exists about the secondary residential mobility of the ‘missing people’ of state-subsidized housing programmes. Where do they move to, why do they leave? This comparative study of three of the most significant housing programmes in Africa analysed 101 housing pathways of such people in the capital regions of Ethiopia, Morocco and South Africa. Rejecting a unilateral notion of displacement, I suggest a new conceptual perspective that sees people who do not occupy their allotted housing units as active subjects reconfiguring supply-driven, shelter-centric housing policy according to their own needs, while also being affected by (severe) financial constraints.

Introduction

Following the slogan ‘Cities Without Slums’, initially put forward by the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) and Cities Alliance, many governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America set up new large-scale standardized housing programmes to push national development and modernization efforts (Huchzermeyer, 2011; Croese et al., 2016; Lemanski et al., 2017; Beier, 2022). Through different forms of subsidies, these programmes seek to deliver affordable and adequate housing to low-income households frequently residing in informal dwellings and shacks. Often they are designed as resettlement programmes that displace and relocate entire communities to distant peripheries, where most of the new housing stock is built from scratch and without much attention to livelihood disruptions (Coelho, 2016; Koenig, 2018). Even if people are not forcibly resettled but deliberately place themselves on waiting lists to receive state housing, this mobility still may be understood as de facto resettlement, or as a form of ‘disrupted re-placement’ (Meth et al., 2023), because of a lack of choice regarding the location and type of dwelling, as well as the likely disruption of social and economic relations due to relocation (Beier et al., 2022).

Since Turner's (1968) ground-breaking work there have been repeated concerns that such large-scale standardized housing and (de facto) resettlement programmes miss their target groups (Buckley et al., 2016; Potts, 2020). Unaffordable schemes and maintenance, underserviced sites in inappropriate locations, as well as gentrification would imply that much of the new, state-subsidized housing stock is actually not occupied by those who policy stakeholders call the ‘intended beneficiaries’. These ‘missing people’ of state-subsidized housing and resettlement programmes have either never inhabited their units or vacated their property after a period of residence—but why do they leave, and where do they go?

Mainly due to the methodological challenges of finding such resettled dwellers outside of their resettlement sites (Beier, 2023a), these questions have largely remained unanswered to date, causing accusatory speculations and divergent assumptions. In India and South Africa some policy stakeholders have lamented the deliberate return of missing people to informal settlements—the very places that were intended to be replaced by the new housing estates (Anand and Rademacher, 2011; Charlton, 2018a)—while in Morocco, politicians accused ‘intended beneficiaries’ of being profiteers who were primarily interested in quick cash-ins (Zaki, 2005: 65f). In contrast, South African housing policy has viewed the disposal of new units as a possible sign of successful enabling policy, integrating the original beneficiaries into formal housing markets (Department of Human Settlements [DHS], 2004). However, most scholars have assumed gentrification and the displacement of the ‘missing people’ to worse living conditions, with little conceptual scope for people's own agency (Lemanski, 2011; Koster and Nuijten, 2012: 193; Choi, 2015: 586).

- First, the phenomenon that state-subsidized housing is not occupied by the target group is significant, both in terms of quantity and quality. For example, in Ethiopia and Angola authorities estimate that up to 70% of the original beneficiaries are not living in their resettlement units (UN-Habitat, 2011: 38; Croese and Pitcher, 2019: 414). In Rio de Janeiro, Garmany and Burdick (2021: 2806) estimate that half of the original owners of a central housing estate left after one year. In South Africa this number is assumed to be lower,1 but resales and letting of state houses are subject to heated public debates (Lemanski, 2011; Charlton, 2018a; Beier, 2023b).

- Second, interest relates to methodological concerns. If studies seek to evaluate the effects of housing and resettlement programmes on people's living conditions, it is insufficient to focus only on those people who inhabit housing units at the new sites. Any evaluation will be biased if it leaves out a large group who do not occupy their new units (Beier, 2023a).

- Third, and most relevant for this article, interest is linked to the need for a profound conceptualization in order to make sense of non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility. Is this yet another form of displacement of a marginalized population, or an act of self-determination amid top-down housing supply? Should departure from state-subsidized housing be opposed and seen as a sign of policy failure?

Following these questions, this article sheds light on the ‘missing people’ of large-scale housing and resettlement programmes, conceptualizing their departure from state-subsidized housing within a people-centred, antithetic continuum of constraint and agency. Based on a reconstructive analytical approach to the housing pathways of these ‘missing people’, I argue that non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility can be understood as demand-driven practices related to coping with, resisting and adapting to the shortcomings of supply-driven housing policy. They represent restricted but mindful and people-led reconfigurations of standardized policy, reflecting both the people's own agency and severe policy constraints in terms of affordability, uniformity and displacement.

The article is comparative in nature, focusing on three of the most significant affordable housing programmes in Africa and their implementation in the capital regions of Ethiopia, Morocco and South Africa. Despite considerable differences in terms of their allocation processes, the types of dwelling and their funding schemes, all three programmes share a common agenda to fight informal housing. Taking the MDGs and the slogan ‘Cities Without Slums’ as common points of reference, they all intend to provide homeownership to low-income households residing largely outside formal markets. Field research took place in Gauteng (October 2020– April 2021), Rabat-Salé (and additionally in Casablanca) (September 2021) and Addis Ababa (March–April 2023). I conducted 101 biographic interviews with recipients of state-subsidized housing who had either never inhabited their new units or who had vacated them after some time, either to sell them or rent them out. Using Clapham's (2005) housing pathway approach as an analytical framework, interlocutors narrated their own housing trajectory and offered comprehensive insights into the residential decision-making underlying non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility.

In the following, I will first sketch out the significance of secondary residential mobility within large-scale state-subsidized housing and resettlement programmes. After briefly summarizing the state of the art, I will give particular attention to the agency of the ‘missing people’. Thereafter I present the case studies, and discuss my comparative methodological approach in more detail. Then I introduce a typology of non-occupation and secondary residential mobility, which I developed based on my empirical work and which uses the interplay of agency and constraint as a guiding continuum. Subsequently, I discuss four different types of departure from state-subsidized housing, ranging from severely constrained moves to more deliberate relocation.

Large-scale housing programmes and secondary residential mobility

The renaissance of state-subsidized, standardized and supply-driven housing programmes may be seen as grounded in both neo-paternalistic welfarism and globalized developmentalism (Civelek, 2017; Beier, 2022; Meth et al., 2023). Although being clearly linked to globally inspired, exclusionary and neoliberal urban renewal agendas (Huchzermeyer, 2011), these programmes are framed as pro-poor, promising to offer ‘better’ housing futures (more modern, more comfortable, more secure, formal, etc.) despite the imposition of relocation and a narrow focus on shelter that ignores wider functions of adequate housing (Coelho, 2016; Beier, 2022). Conceptually, the ways in which relocated citizens are conceived either as ‘beneficiaries’ (cf. Turok, 2016; Hernández Bertone et al., 2022) or as ‘displaced/project-affected persons’ (cf. Koenig, 2018; Nikuze et al., 2022) may reflect this ambiguity (Beier et al., 2022). It is also evident in divergent conceptual perspectives on social housing estate regeneration in Europe (cf. Kleinhans and Kearns, 2013; Watt and Morris, 2024). Indeed, recent studies of state-subsidized housing and resettlement programmes stress the paradoxical simultaneities and uncertain temporalities of gain (e.g. shelter quality, property titles) and loss (e.g. livelihoods, social networks), which are perceived very unevenly across resettled dwellers (Doshi, 2013; Hammar, 2017; Leitner et al., 2022; Meth et al., 2023; Beier, 2024a). Questioning the ‘settling’ character of resettlement (Fernández Arrigoitia, 2017), such time-sensitive and people-centred perspectives urge scholars to pay more attention to people's long-term, pre- and post-resettlement lived experiences (Sakizlioğlu, 2014; Wang, 2020; Williams et al., 2022; Spire and Beier, 2024) as well as different scales of place attachment (Watt, 2022). Thus, there is a need to expand analysis of housing and resettlement programmes beyond both precise localities (e.g. resettlement sites) and project frameworks that assume a clear ‘before and after’ and a singular direction of moving.

Against this background, many studies of state-subsidized housing and resettlement programmes worldwide have taken (a side) note of secondary residential mobility and the non-occupancy of new housing units by ‘intended beneficiaries’.2 In francophone research contexts the phenomenon is known as the ‘dropout’ (glissement) of intended beneficiaries from housing programmes (Le Tellier and Guérin, 2009: 662; Navez-Bouchanine, 2012: 170). In this article I suggest a more neutral approach, referring to the non-occupancy of state-subsidized housing units by their recipients at a certain moment in time after housing allocation. Since recipients are usually expected, required or even forced to move out of their previous dwellings to inhabit their allocated units, non-occupants must have found alternative accommodation at dispersed locations elsewhere. This is what I will call secondary residential mobility, which can take place either after relocation to the allocated housing unit or without any period of habitation. Secondary residential mobility can be temporary, with a potential later move or return of (parts of) the household to the allocated unit in the future (Charlton, 2018b), and it can also be time-lagged. In Ethiopia, some absentee owners of subsidized condominiums initially continued living in their original dwellings, before they were subsequently evicted and moved to a third place.

Several governments running large-scale housing programmes have regarded non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility as undesirable phenomena and as a diversion of public funds, notwithstanding some policy documents framing resales as a sign of successful upward mobility (Anand and Rademacher, 2011; Lemanski, 2011). Typically, policy stakeholders are concerned that people will return to informal settlements and contribute to a proliferation of the very neighbourhoods that the housing programmes were intended to replace (Charlton, 2018a: 2172). Politicians and administrative officials, but also ordinary people, have condemned resales as illegitimate profit-seeking or as a waste of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity (Zaki, 2005: 65; Lemanski, 2014: 2947; Hernández Bertone et al., 2022: 77). Hence, several governments have passed clauses that prohibit the transfer of subsidized housing units within a certain period of time, although these have had limited success. As a consequence, most secondary residential development takes place in a clandestine manner, which tends to lower prices and increase risks for both purchasers and sellers (Charlton, 2018a; Garmany and Burdick, 2021; Mbatha, 2022).

However, to date there is only a limited body of research dealing explicitly with lived experiences of secondary residential mobility (Charlton, 2018b; Garmany and Burdick, 2021; Beier, 2023b; 2024b), making it difficult to evaluate such concerns and policy responses. This is mainly because of its illicit nature, and the methodological challenges discussed below (cf. Beier, 2023a). Thus, there is a significant need for a comprehensive, and especially people-centred, conceptualization of the phenomenon. So far most authors have tried to understand secondary residential mobility as an outcome of (hybrid) gentrification and downward-raiding, whereby more affluent population groups purchase or rent state-subsidized housing from the original ‘beneficiaries’ (Payne, 1997; Navez-Bouchanine, 2012: 170; Lemanski, 2014; Choi, 2015: 586; Leeruttanawisut and Yap, 2016; Civelek, 2017: 421; Croese and Pitcher, 2019: 414; Debnath et al., 2019; Garmany and Burdick, 2021; Williams et al., 2022). These authors suggest that state subsidies end up benefitting the middle class, assuming a further exclusion of ‘intended beneficiaries’ who are pressured to move (back) into worse housing conditions, typically informal settlements. Concerning Cape Town, Lemanski (2014: 2955) argues that ‘the poor are not simply sacrificing their current accommodation but potentially their only chance for decent housing.’

Regarding the reasons noted in the literature as to why people leave their subsidized units, one may differentiate between two logics, namely affordability constraints and opportunism. Regarding affordability, Pankhurst et al. (2022: 252) note that in Addis Ababa ‘some poorer households could not afford the mortgage payments and sold their apartments. … Other families rented out their apartments to cover the monthly payments.’ Furthermore, residence in new housing could itself become unaffordable over time (Restrepo Cadavid, 2010; Lemanski, 2014; Debnath et al., 2019). In Rio de Janeiro, Garmany and Burdick (2021: 2807) indicate that ‘new homes … come with new expenses … that make costs of living unaffordable. Not surprisingly, many of these families sell their new homes.’ In contrast, other studies have found that people resell their new properties for more opportunistic reasons, even if they cannot afford to stay in the same area afterwards (Payne, 1997: 21; Civelek, 2017). In Mumbai, for example, ‘cash-ins’ of subsidized housing are common: ‘With real estate values at astronomical highs for much of 2008 in Mumbai, settlers stood to gain approximately 10–20 years of their annual income by … selling their [new] flats’ (Anand and Rademacher, 2011: 1765).

Notwithstanding the validity of a ‘gentrification and downward raiding’ lens, my concern is that such a conceptual framing of secondary residential mobility plays down the (restricted) agency and lived experiences of ‘out-movers’. Lemanski (2014: 2946) rightfully remarks that gentrification and downward raiding both prioritize in-movers, while out-movers are considered ‘displaced’ and eventually disappear from both the sites and the focus of research. There is little concern about where displaced people decide to move afterwards, for which reason they choose a particular location, and how they experience their mobility—long-standing concerns with displacement research also in the global North (Atkinson 2000; Elliott-Cooper et al., 2020).3 When scholars mention possible directions of secondary residential mobility, they frequently report assumptions that people return (close) to their former places of residence (Choi, 2015: 587; Garmany and Burdick, 2021: 2806; Hernández Bertone et al., 2022: 77). Concerning a housing and resettlement project in Luanda, Croese and Pitcher (2019: 414) report testimonies that ‘a shortage of employment, infrastructure and services initially drove many residents … to sell or rent out their [new] houses … and return to the city core’. The question of whether the returning households themselves see this move as a step backwards, or whether they feel they have made progress in life, remains unanswered.

In fact, residential decisions behind secondary residential mobility appear to be more complex than gentrification-induced displacement would assume. If one accepts that people merely ‘end up handing [new housing] over to the more affluent population’ (Choi, 2015: 587, own emphasis), there is little analytical scope for the more purposeful, strategic, and emotional dimensions of residential decision making. Therefore, I join recent calls to value the experiential dimension of displacement and resettlement (Elliott-Cooper et al., 2020; Hirsh et al., 2020; Beier et al., 2022), foregrounding people's constraints and agency behind secondary residential mobility. In doing so, I build on Clapham's (2005) analytical framework of a housing pathway to understand how people perceive and navigate changing housing contexts, and how they practice housing and attach meaning to it over time. The housing pathway approach helps to bridge structural constraints and individual agency, and can also frame residential mobility as a biographic experience of making and being at home under conditions of change (cf. Blunt et al., 2021). Here, a time-sensitive notion of home enables us to stress the more subjective, emotional dimensions that shape experiences of (partially) enforced mobility (Brickell et al., 2017), which are too often ignored by shelter-centric housing programmes. Consequently, I conceive not only primary resettlement (Beier et al., 2022) but also the experience of secondary mobility as being shaped by a simultaneity of displacement and relocation, understood as the ‘intensely felt and experiential process of un-homing’ (Elliott-Cooper et al., 2020: 498, own emphasis), and the complementary (im)possibilities of multi-scalar re-homing (Deboulet and Lafaye, 2018; Watt, 2022). From here we may begin to enquire about the reasons for non-occupation, and whether households themselves consider their secondary residential mobility to be progressive or regressive.

Case studies and methodology

Following Robinson (2022: 125), I designed the present study in a generative comparative manner treating non-occupation and secondary residential mobility as ‘shared features’ of state-subsidized housing programmes. In line with Ren's (2022) call for a more global approach to urban theory-building, I intended comparison to enable a conceptualization of non-occupation as a structural phenomenon of large-scale, supply-driven programmes beyond (but, of course, not detached from) local particularities. I selected three of the most significant housing programmes on the African continent, embodying a recent turn towards supply-driven housing policy (Croese et al., 2016). The Integrated Housing Development Programme (IHDP) in Ethiopia, South Africa's post-apartheid housing programmes, and Villes Sans Bidonvilles (VSB, Cities Without Slums) in Morocco all give priority to high-quantity, top-down production of state-subsidized, standardized housing at the urban peripheries. This ‘affordable housing’ is intended to facilitate access to homeownership for low-income households who do not own formal property yet.

The programmes’ common points of reference are the MDGs and the related international policy slogan to achieve ‘Cities Without Slums’ (Huchzermeyer, 2011: 115; MHUPV, 2012: 14; Imam and Yonas, 2018: 132). Thus, they all target a physical reduction (if not an eradication) of so-called slums and shacks, which are perceived by policy stakeholders as incompatible with national development and modernization agendas (Meth, 2013; Beier, 2022; Di Nunzio, 2022). While providing different kinds of housing—ranging from condominiums in high-rise housing estates in Addis Ababa to the provision of plots for self-construction in Rabat-Salé and basic free-standing houses in Gauteng—all three programmes are emblematic of shelter-centrism that prioritizes ‘material decency’ (Beier, 2022), while ignoring wider socio-economic dimensions of adequate housing (Huchzermeyer, 2010; Planel and Bridonneau, 2017; Imam and Yonas, 2018; Williams et al., 2022; Beier, 2024a).

Despite striking similarities among the three programmes, there are important differences concerning the precise modalities of housing provision (see Table 1). In Morocco, housing provision through the VSB programme is effectuated by direct resettlement alone (World Bank, 2006; Bogaert, 2018; Beier, 2024a; 2024b). The VSB programme exclusively targets households who reside in bidonvilles (shantytowns), irrespective of their income. They are asked to demolish their original dwelling and then enter a relocation scheme that resembles sites-and-services approaches. In the observed project in Salé, households pay for half a subsidized plot on which they must then construct a three-storey house together with another relocated household. Given that state-backed mortgages remain largely inaccessible (Le Tellier and Guérin, 2009), households have to bear the costs of construction themselves.4 To diversify the sample, I also observed a case in Casablanca, where resettled households received the right to purchase a subsidized apartment.

| Addis Ababa | Rabat/Salé and Casablanca | Gauteng City Region | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing type | Condominiums | Apartments and plots for self-building | Mostly free-standing houses with yards |

| Mode of access | Lottery; resettlement of shack dwellers | Resettlement of bidonville dwellers | Waiting list; resettlement of informal settlements |

| Financial contribution | Down payment and monthly mortgage payments | Subsidized purchase price; self-building (in case of plots) | Free for low-income households |

In Ethiopia's IHDP programme (UN-Habitat, 2011; Planel and Bridonneau, 2017; Pankhurst et al., 2022), housing provision in Addis Ababa takes place through direct resettlement of shack dwellers and also via a lottery system to which citizens may apply if they do not own property. Depending on their income level and capacity to save up, households may choose to register for condominiums of different sizes ranging from studios to three-bedroom units. Once their name is drawn, they have to use their savings for an initial down payment (minimum 10% of the total price of the condominium) and then pay monthly mortgage instalments for 15 to 20 years.

Among the three programmes under investigation, South Africa's housing scheme is the only one that provides housing units to eligible persons free of charge (Meth, 2013; Huchzermeyer and Karam, 2016). Households who do not own property and earn less than ZAR 3,500 per month (approximately EUR 175) may sign up to so-called ‘waiting lists’, through which they might receive – often after years of waiting – a basic, free-standing, often one-roomed top structure colloquially known as a ‘RDP house’, alluding to the post-apartheid Reconstruction and Development Programme. While allocation through waiting lists is common, in Gauteng the direct resettlement of entire communities as well as the in-situ provision of RDP houses take place as well.

In all three programmes, non-occupancy by recipients and secondary residential mobility are significant phenomena that have featured prominently in housing policy debates. Whereas government actors in South Africa have rather shown a hostile attitude towards any kind of non-occupation (Charlton, 2018a; Beier, 2023b), the Ethiopian government has seemed more tolerant towards people renting out state housing units (UN-Habitat, 2011: 38). In Morocco, high levels of glissement have led to policy change, partially towards more repressive modes of implementation ensuring the definite demolition of shacks, and temporarily towards more inclusive financing schemes (Le Tellier and Guérin, 2009; Beier, 2021; 2024b). In fact, all the programmes include clauses that prohibit the resale of received housing units within a certain period of time after allocation (five to eight years).

A typical challenge for the study of non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility is locating, contacting and interviewing former dwellers. As an ‘unconsciously hidden population’ (Beier, 2023a), the ‘missing people’ of state-subsidized housing programmes live at dispersed locations across the entire metropolitan area. Moreover, even if it is possible to locate them, they might be hesitant to talk due to the (perceived) illicit nature of their non-occupancy (Lemanski, 2011; Garmany and Burdick, 2021). For this research, therefore, I developed and applied insider-driven snowball sampling techniques that could effectively counteract these challenges for sampling in terms of both hidden location and reluctance to talk.5 Thanks to my research assistants and our context-specific adaptations of sampling procedures, it was possible to realize a total number of 105 narrative biographic interviews, of which 101 fulfilled all the criteria to be considered ‘missing people’ for this study.6 Of these interviews, 35 took place in Addis Ababa (March–April 2023) and 27 in the Gauteng City Region (GCR) (October 2020–April 2021). Of the 39 interviews conducted in Morocco in September 2021, 29 took place in Salé, mostly with interlocutors who had sold their resettlement plots. To increase diversity my colleague Manon Troux conducted ten additional interviews with people in Casablanca, who had received apartments as resettlement compensation. Table 2 offers an overview of all the interviews, showing that the case studies offer a diversity of allocation practices and forms of (de facto) resettlement. Before embarking on a more detailed discussion below, it is clear from Tables 1 and 2 together that specific modes of implementation (e.g. access free of charge) influence the type of departure (renting out vs. selling) and whether recipients have previously occupied their units.

| Temporarily inhabited (incl. potential return) | Never inhabited, but intending to | Never inhabited (incl. unintended but potential return) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sold/selling | Renting out | Renting out | Sold/selling | Renting out | |||||||||||

| ETH | MAR | RSA | ETH | MAR | RSA | ETH | MAR | RSA | ETH | MAR | RSA | ETH | MAR | RSA | |

| Access through waiting lists or lottery | 4 | - | 6 | 3 | - | 8 | 5 | - | - | 6 | - | - | 8 | - | 4 |

| Access through resettlement (incl. in-situ) | - | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 27 | - | 2 | 4 | - |

- Special cases: 3x resettlement, never inhabited and unable to access (MAR); 1x accessed through waiting list, not staying permanently (RSA); 1x resettlement, unable to access, 1x lottery, unable to access (ETH). Total number of interviews: ETH: 35; MOR: 39; RSA: 27.

The narrative interviews were designed to incite respondents to talk freely and to narrate their personal ‘housing pathway’ (Clapham, 2005). If an interlocutor was hesitant about talking freely, we used basic follow-up questions to explore their past (and future) reasoning behind moving house. This holistic approach to enquiry acknowledges the complexity of moving decisions, reflecting biographic experiences (including aspects of family, gender and age) and wider socio-economic contexts (including employment and social conflicts). Except for six interviews in the GCR, one in Addis Ababa and those that took place in Casablanca, the author was present for all interviews, which lasted around one hour on average. They were conducted in several local languages as selected by the interviewed person, with the assistance of experienced research assistants fluent in these languages. The interviews were transcribed and translated into English (ETH, RSA) and French (MAR) and analysed thematically using MAXQDA. Schematic representations of each elicited housing pathway allowed for a sequential and reconstructive comparative analysis, which was helpful in developing a typology across the diverse case studies.

The ‘missing people’ between constraint and choice

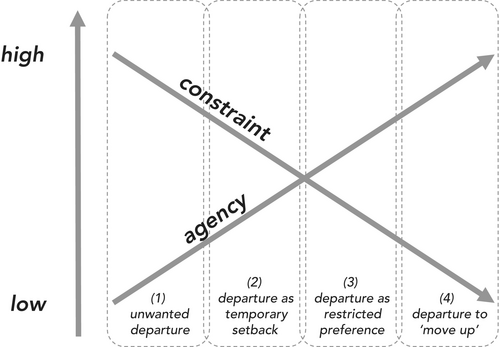

From the comparative analysis of the interviews, I derived a typology organized around the extent to which agency and constraint shape people's decisions not to inhabit state-subsidized housing units. Recognizing ambiguous conceptualizations of housing and resettlement programmes in both the global North and South (Kleinhans and Kearns, 2013; Deboulet and Lafaye, 2018; Hammar, 2017; Beier et al., 2022; Meth et al., 2023), the selection of agency and constraint as key variables goes beyond a mere displacement lens, which tends to foreground involuntary experiences of ‘un-homing’ (Elliot-Cooper et al., 2020; Watt and Morris, 2024). Acknowledging people's more or less limited power and desire to shape their own housing futures, this typology is also able to account for people's attempts at and practices of ‘re-homing’ (Deboulet and Lafaye, 2018; Watt, 2022; Meth et al., 2023). In this sense, agency and constraint are seen as two inversely related variables that shape each moving decision to a varying degree. Along the heuristic continuum shown in Figure 1, one may distinguish four positions representing different categories of types of departure: 1) unwanted departure, 2) departure as temporary setback, 3) departure as restricted preference, and 4) departure to ‘move up’. It is important to note that these are not rigid categories; rather, they are overlapping and fluid. For example, over time a particular respondent's decision-making may align with more than one type. Nevertheless, they are helpful tools to explore the spectrum of non-occupation and secondary residential mobility.

(source: the author)

Unwanted departure

The first category comprises unwanted departures from state-subsidized housing, without the option to return and mostly because of unaffordability. Typically, this involves the most destitute and disenfranchised individuals who have no other option than to sell their (right to a) dwelling or plot before inhabiting because of the required costs (i.e. a down payment in ETH, construction costs in MAR). However, depending on the housing scheme this category may also include households with regular income sources as well. In schemes like the one in Salé that demand high financial contributions from the eligible population but largely without the option of accessible financing, this type of secondary residential mobility is relatively frequent compared to schemes that allocate units for free (as in RSA). For this reason, across all the case studies unwanted departures were most prevalent in Rabat-Salé: ‘It's not that I didn't want to go … it's a financial problem. … I'd live [at the resettlement site] in Bouknadel and I'd struggle [for it] … but I'm nothing, man. I've got nothing, I don't have the money to build [the house]. You need a lot of money!’ (MA01, Yahya, M, 28, car washer).7

However, unwanted departures may also involve people who received housing for free but who could not afford to sustain habitation. One example is Nomvula (SA05), an older woman heading a large single-parent household in Braamfischerville, Gauteng: ‘I am struggling financially! No one is working here in this house (ekhaya), not even one person is working. We then agreed to put the house up for rent’. In some cases reasons other than affordability play a role; relocated people were forced to leave resettlement housing because the new house was in danger of collapsing (CAS05), or because of community problems (SA22) or family issues (ET22; CAS10; SA12).

As this first category is characterized by the highest level of constraint, destinations for secondary residential moving were the least costly (though often more costly than original dwellings before relocation), the most undesirable, and were often provisional forms of housing, including different forms of informal renting, shared dwellings and makeshift shelters in central areas, as well as shacks in emerging informal peri-urban settlements. Some people in this category also decided to leave the city altogether. However, while financial constraints are the most significant in this category, agency may still matter in terms of where exactly people decide to move to. For example, Souad (MA21, F, 51) and her brother deliberately decided to move further away from where they used to live before, even though they had limited other options. For them, failed resettlement—despite all the hardship—felt like a chance to change and break with what Souad saw as detrimental habits for her brother and her children.

However, because of constrained options the new living conditions are often perceived as worse than before the allocation of state housing, especially if housing programmes force people to leave their previous homes. An extreme example is Tesfaye (ET22, M, 41, day labourer), who sold his family's resettlement condominium because of an inheritance dispute with his sibling and who now lives in a makeshift plastic shack (yeshera bet) that is repeatedly demolished by public authorities. Usually, however, worse living conditions are the result of an increase in living costs. In Salé and Casablanca, informal settlement dwellers used to be owner-occupiers, but many of those who were unable to afford resettlement now struggle to pay rent even for the cheapest rooms, mostly located in consolidated informal neighbourhoods (habitat non-réglementaire) and which often involve temporary agreements and shared facilities. A typical example is Safiya (CAS10, F, day labourer), who could not occupy her resettlement flat in Chelalat: ‘There are no windows, just darkness, where I live at the moment. I didn't find any alternative, so I moved in. Now I am searching, but still can't find anything. Everything is expensive. I don't have the money. A flat with a window is expensive'. In addition to inadequate shelter quality, the financial constraints of rental accommodation further increase the pressure on poor households to dispose of their allocated housing units or plots to escape from rent; Safiya went on to say, ‘If only I had a room of my own … I often fall ill, and when I do, I'm not able to work, but the rent has to be paid in any case!’

However, even if housing programmes do not immediately force people to leave their homes, living conditions may still worsen as a result of unwanted departures. Because of the violent urban renewal of Addis Ababa and the related severe housing shortage, several respondents who could not access allocated flats now felt hopeless and often anxious about the repeated forced evictions. Deme (ET15, M), a 30-year-old day labourer who suffered from repeated rent increases and displacements, felt unable to secure a sustainable future in the capital after he could not afford the down payment for an allocated condominium. He wished to return to the countryside, where his earlier life felt less stressful, but he did not dare to return as someone who could not make it in the city. To escape rental accommodation he was considering buying at the periphery, where low-quality shacks were still affordable although they were frequently demolished by local authorities.

Safiya's and Deme's unstable situations and their insecurity in relation to the future are typical in cases of unwanted departure. In the Ethiopian and Moroccan case studies, most of the secondary residential movement in this category is characterized by experiences of and vulnerability to ‘recurrent displacement’ (Watt, 2018), related to both financial pressures and the uncertainties of rental accommodation as well as state-led evictions from makeshift shacks and emerging informal periurban settlements. As such, agency often tends to be limited to a compromise achieved by balancing the severe risks associated with different available housing options. For example, for Deme it was worth the risk to buy at the periphery, but for the day labourers Abera (ET12, M, 47) and Chaltu (ET16, F, 63), leaving rental accommodation in the area where they lived was not an option, even despite recurrent evictions and rent increases, because for them local networks were the most significant.

Departure as temporary setback

While living situations after departure are unlikely to improve in cases of unwanted departure, the second category describes departure as a temporary setback that contains genuine hope for a more positive future, either inside or outside state-subsidized housing. Here, people currently cannot sustain residency inside their allocated housing units, so they move out and typically rent their unit out. They accept a short-term decrease in their living conditions in order to cope with current constraints and secure the future long-term habitation of their received dwelling or a decent alternative. These people are slightly better off than the first group of people, but many still regret their departure and feel forced to live outside their received houses, which represent home. These feelings are more common if received units can be rented out and are therefore less relevant in Rabat-Salé, where most respondents had received plots for self-construction.

Reasons for temporary non-occupation are diverse, with affordability playing an important role. In Gauteng it was typically related to questions of habitability. For example, Aaron (SA16, M, ~55, general worker) explained that he could not afford to make the necessary investments in his one-roomed ‘RDP house’ so that it could accommodate the entire family: ‘Sometimes I have a job, sometimes I don't. I am not able to extend the house and live nicely with my kids, you see. At the same time there should be bread on the table, so we decided that we will rent the house out’. Meanwhile, in Addis Ababa it was common for people to rent out their condominiums in order to afford their monthly loan instalments. For example, Berhanu (ET03, M, 45, driver) said, ‘My plan is to move there in this year. … I plan to collect my equb [rotating saving scheme] to pay the [remaining] debt …. If I take the equb, I will reduce the debt greatly and I will enter’. Beyond acquisition costs, resettlement to a more distant location could affect people's capacity to inhabit state-subsidized housing. Betelhem (ET28, F, 38, guard) reported that it was currently impossible for her to inhabit her condominium because it was too far from her place of work, but she was hoping that her employer would soon provide free and reliable transport for employees. Other financial constraints driving temporary non-occupation were not directly linked to the house itself, including unemployment, inflation or school fees. In such cases state-subsidized houses may function as a form of social security, enabling people to cope with crises or shocks – for example, the loss of the household's sole breadwinner, as in the case of Katlego (SA07, M, ~25, unemployed): ‘I try to get back on my feet. … Maybe I'm renting the house, then try to save some money … I want to get my license done, so that I can get a better job. … Then I come back home’.

In terms of their secondary moving decisions, most respondents in this stage of the continuum (see Figure 1) accept difficult if not much worse housing conditions than before. Aaron lived in an informal settlement that he referred to as ‘rough’ because of its high crime rate, while Katlego was uncomfortable about moving into the home of his distant family. In Addis Ababa, in many cases temporary non-occupancy of allocated housing meant that people were at risk of repeated eviction; an extreme example was the case of Meselu (ET29, F, 30), a public servant who could not yet afford to live in her condominium which was located about 20 km away from her workplace. Together with her husband, Meselu spent her entire salary of ETB 2,000/month8 on housing, but had already been evicted twice by landlords, each time being forced to move to a lower-quality dwelling. Whereas about five years earlier they had been able to rent a decent house for ETB 2,000/month, now they could only find an informal residence (chereka bet)9 in the same area, which had a leaking roof and neither water nor electricity. While Meselu hoped that a job promotion would allow her to move to her condominium in the near future, others preferred not to move (back) to their received units. In Salé, Malika (MA14, F, 36, housewife) said it was impossible to live at the resettlement site because of its peripheral location. While searching for alternative housing and a buyer for her plot, she accepted a setback and moved into a small, shack-like room on the roof of her family's house, in order to save on rent: ‘I used to be independent, and became imprisoned again’. After a long, tiresome search she managed to buy a decent étage10 on credit and now felt she had been released. Thus, Malika may be positioned between positions two and three on the continuum (see Figure 1), with her new flat being preferred over resettlement housing.

Thus, temporary departure is characterized by relatively high constraints, both financially and in terms of housing conditions. However, the scope for people's own decision-making is higher than for unwanted departures. Agency and constraint are often closely entangled, showing the inadequacy of a clear-cut understanding of forced vs. desired residential mobility (Meth et al., 2023; Beier, 2024a). For example, despite his severe financial constraints, Aaron only mentioned at the end of the interview that he decided to move out of his ‘RDP house’ when he received an outstanding offer from a tenant. Hence, forced displacement and opportunistic rationales may not be mutually exclusive.

Departure as restricted preference

Thus, for respondents aligning with type three, moving into state-subsidized housing was not necessarily perceived as an improvement, being experienced instead as un-homing. Respondents like Hawlet did acknowledge the higher levels of comfort of condominiums (e.g. private bathrooms), but even so, non-occupation was usually not perceived as a step back, even if it implied lower shelter quality. Others, like Xolile (SA14, F, ~27, unemployed), even perceived there was no difference in quality between her ‘RDP house’ and the self-built shack that she was now living in.We were living by sharing food and coffee. If someone had injera, the other prepared wote and we ate together. You live in Kirkos with happiness, I like it! There is no closed door … However, [in Jemo] no one knows you … even no one greets you … It is disgusting … You feel lonely … Compared to life in condominiums, currently we are happy. Now, we can at least see people around us, we drink coffee together with neighbours. … The life in condominiums does not match with our life. … You only find supermarkets in Jemo. In Kirkos you can get commodities at a cheap price but in Jemo you will not find them.

People's moves into lower-quality and/or informal housing were often the result of financial constraints. Other places were out of reach because purchase prices for peripheral and badly equipped state-subsidized housing tend to be low, partially as a direct result of resale bans (Mbatha, 2022). Sometimes new living conditions are even perceived as worse than prior to the receipt of state-subsidized housing, even though they may still be preferred over a life in the latter. After displacement from her home in Kazanchis, Beshadu (ET27, F, 36, guard) refused to inhabit her condominium and moved to another place in Kazanchis. Now, she was concerned about state-led demolitions driving urban change: ‘When there was no injera at home, you could take injera from your neighbours, drink coffee together. All mothers in the neighbourhood seemed like your mother. Now this community is dispersed. … The government makes Kazanchis disappear!’ While respondents in the second category felt forced to move out of their received housing units, in the third type more people felt forced to move into their condominiums, which were seen as a last resort after eviction from their places of belonging.

However, questions of affordability do overlap with people's desire not to inhabit their received units. Simultaneously, people may be unwilling and unable to occupy them. In Salé, Mohammed (MA08, M, 38, ticket agent) did not have the means to build his resettlement house, but at the same time he could not imagine inhabiting a peripheral place like Bouknadel, where he would fear crime, suffer from a lack of transport options, and miss the proximity to public services as well as work. He was therefore happy to trade his plot for an unregistered étage in Hay Inbiat, a popular place not far from where he had lived before: ‘Bouknadel is going to get even dirtier than it is now … I came here to Hay Inbiat, the hospital is next door, the police station is next door, the markets are next door, you just have to say what you want …’ Mohammed's choice of an unregistered étage in Hay Inbiat is typical in this category, because it shows that many respondents aligning with type three prefer secondary moving destinations close to their former places of residence, if possible (cf. Choi, 2015; Garmany and Burdick, 2021).11 Similarly, Brahim (CAS03, M, ~37) argued, ‘Here, I can go back home at one in the morning, I am still feeling safe. I can go out wherever I want, I know all people!’ Right from the beginning, it was clear to him that he would not leave the neighbourhood where he grew up.

Departure to ‘move up’

The last category, ‘departure to move up’, was the least frequently encountered across all the case studies. This involves non-occupants who have moved out of state-subsidized housing to purchase a new dwelling in a higher segment of the formal housing market, such as large, detached houses or new apartments. This position on the continuum is closest to the neoliberal idea that people might use state-subsidized housing as a starter asset, in which they invest and which they can subsequently sell to enter the formal housing market and ‘move up’ the housing ladder (cf. Lemanski, 2011). In contrast to type three, respondents aligning with this type have usually inhabited their received dwellings for a long period before moving out.

Typically, this group comprises people with more secure forms of employment and relatively high regular income, such as bank employees (MA19), shop owners (MA15) and embassy employees (ET01). Their regular work may help them to save money and to access credit. Nombulelo (SA30, F) traded a lower-quality ‘RDP house’ against another one of better quality, and was aware that this was possible only because of her employment at a hospital: ‘At least I was registered at work. I have the power to go and buy a house. I will add money to what I got when I sold the house’. In addition, some respondents were able to make use of an increase in the value of their state-subsidized housing unit. For example, the librarian Lemlem (ET32, F, 58) was among the first people to receive a condominium from the state, at a time when the condominium site in Gerji was peripheral: ‘It seemed like countryside. When we moved there, our family was crying since it was too far from the centre … There was no taxi to go there, but now it is a part of Addis Ababa's centre. It is a beautiful area now!’ House prices in Gerji increased quickly, and allowed Lemlem to sell her condominium and raise enough to purchase an eight-room house with title deeds just outside Addis Ababa's administrative boundaries.

Reasons for a ‘departure to move up’ often relate to the size and condition of state-subsidized housing. For example, Lemlem explained, ‘I didn't dislike my condominium, the only problem was its size. It couldn't accommodate my family’. Long-term habitation of state-subsidized housing in multiple ownership may also raise concerns about maintenance; Nizar (MA19, M, 31), who had bought a new apartment, argued, ‘In the new house, we want to contribute to maintenance, but in the old house it was impossible. … There are people who really don't have the means, [those ones] you can understand, but people who have the means and think it's unnecessary, that's the problem. For me, that was the main reason I decided to move!’ For others such as Aziz (MA02), Lahcen (MA15) and Kagiso (SA29), departure was also a way to leave neighbourhoods that they considered ‘bad’ or ‘poor’.

Clearly this category involves deliberate movement, but even here constraints still affect people's secondary residential mobility. In the case of Lemlem above, higher housing standards may come with the need to accept (more) peripheral locations and similar drawbacks. As such, value increases in state-subsidized housing may enable recipients to access bigger and higher-quality housing, but this might also push them further to the periphery. For example, Sisay (ET19, M, ~50, secretary) was thinking about trading his one-room condominium in Tulu Dimtu for a bigger one in Koye Feche, a more recent, and therefore less established and slightly more peripheral, resettlement site: ‘Now, I am living in one bedroom. If I sell this condominium, I can buy two bedrooms in Koye Feche. Now, my children are young and they are sleeping on the floor, but they are asking for an independent bedroom. Thus, if I move to Koye Feche, they will have their own bedroom’.

Conclusion

Non-occupation of state-subsidized housing and secondary residential mobility are important phenomena—both in terms of quantity and quality—affecting large-scale housing and resettlement programmes in Africa and beyond. However, common conceptual lenses rooted in gentrification theory or downward-raiding are biased towards the idea of displacement. They tend to restrict reasons for non-occupation to notions of coercion and opportunism, while struggling to account for the agency of people who are ‘missing’ from resettlement sites. Moreover, they are unable to account for the diverse destinations of secondary residential mobility, and the complex decision-making behind it. Given the wide range of literature concerned with the deficiencies of the peripherally located and under-serviced sites chosen for standardized housing programmes (Buckley et al., 2016; Koenig, 2018; Williams et al., 2022), it seems unsatisfactory to reduce explanations for departure from state-subsidized housing to households’ mere inability to finance long-term residency. Instead, this phenomenon should be conceived as a multi-dimensional demand-driven response.

Because of the outlined shortcomings and based on a generative comparison of biographic narratives of non-occupants, I have suggested a people-centred typology differentiating four positions along an antithetic continuum of agency and constraint (see Figure 1). However, this is not intended to downplay the relevance of downward-raiding and displacement. Indeed, for several respondents non-occupation predominantly represents an experience of un-homing. Nevertheless, other respondents deliberately choose not to occupy their allocated state-subsidized housing in order to re-home at places of belonging and/or desire. Therefore, the suggested typology goes beyond a singular emphasis on displacement, offering a much-needed complementary perspective that combines a conceptual emphasis on experiences of un-homing and re-homing (Beier et al., 2022; Meth et al., 2023). Thus, in line with literature exploring life after displacement and housing provision (Kleinhans and Kearns, 2013; Lemanski et al., 2017; Deboulet and Lafaye, 2018; Charlton, 2018b; Wang, 2020; Watt, 2022), it enlarges the temporal frame of analysis and looks beyond a single site. Most significantly, it helps us to conceive of people who depart from state-subsidized housing as active subjects who reconfigure supply-driven, shelter-centric housing policy according to their own, future-oriented demands, while at the same time being affected by different degrees of financial constraints.

These financial constraints often relate to the direct costs of housing acquisition, which appear to have the most significant impact on the extent of non-occupation in a particular setting. While Morocco's non-inclusive resettlement scheme produced a high number of ‘unwanted departures’, these were less common in South Africa where houses were provided for free. At the same time, the findings stress the importance of decent labour (Potts, 2020), clearly showing that a higher degree of agency—i.e. a higher capacity to direct one's own housing pathway—is strongly linked to more secure forms of employment. Thus, the conceptual emphasis on restricted but mindful and people-driven reconfigurations of standardized housing policy intends to balance the structural and individual factors driving non-occupation. As such, some forms of non-occupation appear as individual strategies to resolve structural constraints (e.g. location, mortgage costs) and to sustain future residency within state-subsidized housing—most commonly in Addis Ababa and Gauteng (Charlton, 2018b; Pankhurst et al., 2022).

In terms of the destinations of secondary residential mobility, my findings may partially confirm concerns about downward-raiding and returns to inadequate housing. However, from the perspective of the ‘missing people’ this should not automatically be seen as regressive, or solely as an enforced form of residential mobility. Rather, most respondents aligning with types two and three make better use of state-subsidized housing if they do not occupy it, instead renting or selling it. They tend to be better off in terms of living conditions than before they received state-subsidized housing because of new rental income, more security, and/or better housing comfort. Geographically, it is also too simplistic to assume displacement towards the urban peripheries. Paradoxically, some destitute respondents who could not access state housing squeezed into shared accommodation in central locations, while some respondents from the lower middle-class moved even further towards the periphery after they left state-subsidized housing. Thus, a close analysis of secondary residential mobility may suggest a conceptualization of departure from state-subsidized housing not only as a form of displacement, but also as a possibility for people to introduce elements of personal choice into ill-designed and inflexible supply-driven housing policy.

Consequently, I argue that the sale and letting of received units should not be sanctioned. Temporary resale bans or occupancy audits impede people's own pragmatic efforts to overcome the unaffordability of state-subsidized housing, and prevent homeowners from deciding for themselves how to use their assets in their best way under given conditions. Here, my argument aligns with Standing's (2011) critique of conditional cash transfer, as well as Mbatha's (2022) concerns with black-market sales of state housing. In fact, the findings show that non-occupation tends to represent the outcome of a careful, often strategic consideration of different options under considerable financial and structural constraints. Thus, I suggest that people should be free to make their own informed decisions about whether they prefer to occupy allocated units or not.

However, as noted by Audycka (2023), such a ‘right to decide’ should be inextricably linked to the aim of housing programmes to keep the extent of non-occupation as low as possible through inclusive and affordable schemes, limited geographical and social disruption, and opportunities for spatial and economic appropriation at the new sites. Nevertheless, I argue that a recent (re)strengthening of authoritarian and destructive urban policies in Morocco and Ethiopia (Di Nunzio, 2022; Beier, 2024b) is likely to impair secondary residential mobility, raising significant doubts about whether authorities are actually interested in facilitating progressive housing pathways for low-income citizens.

Biography

Raffael Beier, Department of Spatial Planning, TU Dortmund University, August-Schmidt-Str. 6, 44227 Dortmund, [email protected]

References

- 1 In the case of the Westlake community in Cape Town, Lemanski (2014: 2948) estimated a resale quota of 25%. Officials reported even lower numbers for the Gauteng City Region (GCR) (Charlton, 2013: 217).

- 2 The following studies refer to non-occupancy and secondary residential mobility in diverse countries—Angola, Argentina, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Morocco, the Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Türkiye—underlining the commonplace and global nature of the phenomenon: Restrepo Cadavid, 2010; Anand and Rademacher, 2011: 1765; Lemanski, 2011; Koster and Nuijten, 2012: 193; Choi, 2015: 586; Patel et al., 2015: 249; Coelho, 2016: 123; Leeruttanawisut and Yap, 2016; Civelek, 2017; Herath et al., 2017: 567; Planel and Bridonneau, 2017: 32; Charlton, 2018b; Croese and Pitcher, 2019: 414; Debnath et al., 2019; Garmany and Burdick, 2021; Hern.ndez Bertone et al., 2022: 77; Mbatha, 2022; Pankhurst et al., 2022: 252; Williams et al., 2022: 922.

- 3 As Watt and Morris (2024) outline, the Northern discourse on post-displacement experiences has mainly emerged in relation to social housing estate regeneration. Less is known about people who were displaced to dispersed locations.

- 4 In previous, more inclusive resettlement projects in Morocco the state tolerated a third-party investment scheme that facilitated affordability for low-income households by inviting so-called tiers associés to finance the construction of a four-storey resettlement house in exchange for shared property ownership (Beier, 2021). In the observed project in Salé, however, households were restricted to building three-storey houses, which made investments by tiers associés unprofitable. Hence, the third-party scheme did not play a role in this study (Beier, 2024b).

- 5 For a more detailed discussion of these methodological challenges and the applied sampling techniques, please see Beier (2023a).

- 6 To be considered for the study interlocutors had to be original recipients of state housing whose households did not permanently occupy, or intended to vacate, their received housing unit or plot.

- 7 The brackets include the interview number specifying country or city (CAS = Casablanca), the respondent's pseudonym, their gender, age, and occupation. In some cases, this information was not provided, and it is therefore left out here.

- 8 Approximately EUR 30.

- 9 Literally, chereka bet means moonshine house; a reference to their clandestine construction at night.

- 10 By étage, respondents in Salé were referring to a basic flat (often with shared bathrooms) in a multi-storey building in one of Salé's large informally-built working-class neighbourhoods (habitat non-réglementaire). The term étage contrasts the notion of an appartement, which refers to a condominium in a ‘modern’ apartment complex built by a developer.

- 11 Hence, it is not exclusively for financial reasons that respondents choose to opt for an étage rather than an appartement built by a developer, which are mostly located at the urban peripheries. Here, developers have benefitted from subsidized access to land to cater for a lower middle-class able to access credit (Kutz, 2018).