Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of CEO Tenure and Millennial CEO

Abstract

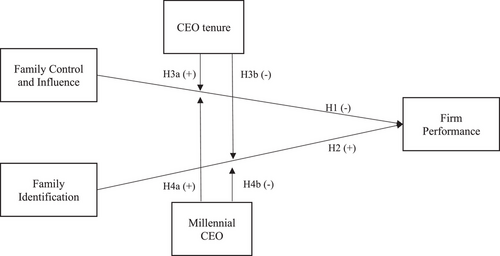

This study sheds light on how socioemotional wealth (SEW) theory functions in family firms. Focusing on the impact of the most highly appraised FIBER dimensions on the performance of such firms, we contextualize SEW by discussing the heterogeneity among family principals via the under-researched role played by specific characteristics of family CEOs. Integrating arguments from SEW and generational theory, we test our theoretical hypotheses using global survey data from a sample of 1833 family firms from 33 countries. The main findings suggest that while family control and influence is not associated with performance, family members’ identification with the firm (FI) improves performance. Moreover, the positive impact of FI on family firm performance weakens in family firms with long-tenured family CEOs. Finally, in family firms led by Millennial CEOs, the positive impact of FI on family firm performance is stronger. Our findings enrich both the theoretical insights into and practical comprehension of SEW priorities in relation to family firm performance, thereby underscoring the diverse performance outcomes associated with various types of family CEOs.

Introduction

Family firms’ uniqueness is largely attributable to the way family principals (e.g. family CEOs) make strategic decisions often based on both non-financial and financial goals. The socioemotional wealth (SEW) approach (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Naldi et al., 2013) largely explains this, suggesting that family principals do not commit to strategic decisions that may cause a loss to their accumulated SEW. Family principals have a strong desire to protect their SEW, which Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007, p. 107) refer to as the `non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family's affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty’. In this context, preventing SEW losses is the foremost reference point for family principals, which frequently results in decisions that deviate from strict economic rationales (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012).

The debate on SEW, its measurement through FIBER,1 and its impact on various family firm outcomes has flourished over the past decade (Swab et al., 2020), thereby advancing our understanding of the existence of heterogeneity within family firms (Chua et al., 2012; Daspit et al., 2021), but also highlighting the need for further understanding of the theory and its boundary conditions. Nevertheless, conflicting findings exist regarding the most significant SEW dimensions and their subsequent influence on family firm performance (FFP) (Hughes et al., 2018; Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016; Williams et al., 2018). This stems from SEW being associated with both positive and negative aspects. Commonly labelled as the `bright side’, positive aspects include long-termism, commitment, and identification with the family firm. The `dark side’ includes nepotism, managerial entrenchment, risk aversion and dynastic family ambitions (Samara et al., 2018; Temouri et al., 2022). Although research has examined how SEW, as a latent explanatory variable, may impact performance (Cruz, Justo and De Castro, 2012; Minichilli et al., 2014; Naldi et al., 2013; Shepherd and Rudd, 2014), few empirical studies have examined how the operationalization of SEW and its distinct dimensions impact performance (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Cennamo et al., 2012; Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016). This study clarifies the functioning of SEW theory within family firms, emphasizing the influence of the most valued FIBER dimensions, specifically, family control and influence (FCI) and the identification of family members with the firm (FI), on FFP. We focus on these two SEW dimensions because family business leaders exhibit the highest appraisal for them in terms of preference (Bauweraerts et al., 2022). They represent family-level constructs aggregated from the perceptions of individual family members.

Moreover, the influence of family principals and the nuances of their characteristics on SEW dynamics are often overlooked (Gómez-Mejía, Neacsu and Martin, 2019; Strike et al., 2015), which is notable, especially given that SEW theory fundamentally revolves around the reference points and preferences of family principals (as highlighted by Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). Therefore, we `contextualize SEW’ theory (Calabrò et al., 2018; Minichilli et al., 2014) by discussing the heterogeneity among family principals through the roles played by specific individual-level characteristics of family CEOs,2 such as CEO tenure (Boling, Pieper and Covin, 2016) and CEO generational cohorts (Cirillo et al., 2022). The length of time a person has held the CEO position, CEO tenure, is an important intervening variable influencing the way family CEOs make strategic choices (Minichilli et al., 2014; Zona, 2016). However, given the lengthy tenures of CEOs within family firms and their enduring impact, the lack of research on the role of CEO tenure in the SEW–FFP relationship is surprising (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012). Additionally, generational cohorts of family CEOs have largely been ignored in family business debates (Debellis et al., 2021; Magrelli et al., 2022). If we consider that SEW primarily explains family principals’ strategic choices based on their preferences (Jiang et al., 2017; Minichilli et al., 2014) and a generational shift exists in the chain of command of family firms around the world, with many Millennial family CEOs taking over the helm of these businesses (Cirillo et al., 2022), this is surprising. Thus, by systematically failing to include such a crucial feature of family principals, analysis risks missing the complex reality behind such a phenomenon. Accordingly, we draw on generational theory (Edmunds and Turner, 2005; Eyerman and Turner, 1998; Gilleard, 2004; Mannheim, 1952). We argue that family firms headed by Millennial family CEOs, a generation distinctively different from its predecessors (Anderson et al., 2017), demonstrate values and traits that subsequently influence the effect of the two SEW dimensions on FFP. This stems from the fact that Millennials were raised during a unique period, marked by distinct political and socio-historical events (Parry and Urwin, 2011). Research maintains that these events develop into systems of similar values, opinions and beliefs (Eyerman and Turner, 1998), which lead to predictable and comparatively similar behaviours (Howe and Strauss, 2007) that are visible in workplaces and management settings (Rudolph, Rauvola and Zacher, 2018).

We empirically analyse data from a cross-country family business dataset launched in collaboration with 48 universities affiliated with the STEP Project Global Consortium,3 a context-sensitive applied research initiative exploring family firms across generations (Campopiano, Calabrò and Basco, 2020; Samara et al., 2018). The data were collected in 2018–2019 via an online survey from a sample of 1833 family firms from 33 countries, with a response rate of 37%. Our main findings indicate that while no significant relationship exists between FCI and FFP, a significant positive one exists between FI and FFP. Moreover, in family firms led by long-tenured CEOs, the positive contribution of FI on FFP is jeopardized, which suggests that having CEOs with long tenure does not help support the positive impact that family members’ feelings of cohesion, belonging, and identification have on performance. Finally, in family firms led by Millennial CEOs, the positive relationship between FI and FFP is further amplified, which suggests a salient reference point for such CEOs' contributions to the FI–FFP relationship.

This study makes several theoretical and practical contributions. First, we advance the debate on SEW theory (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) and its impact on family firm outcomes (Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016) by providing new insights into the competing nature of the most highly appraised dimensions of SEW (FCI and FI) in relation to FFP. While underlining different dimensions of SEW (Bauweraerts et al., 2022; Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012), this advances the research on SEW and financial outcomes (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016) by revealing the nonexistence of a dark side of SEW manifested through FCI (Bauweraerts et al., 2022; Gómez-Mejía, Makri and Larraza-Kintana, 2010), as well as the existence of a bright side manifested through FI (Matherne et al., 2017; Sundaramurthy and Kreiner, 2008). Second, we contribute to the effort to make SEW a `homegrown’ theory within the family business research field (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Hasenzagl, Hatak and Frank, 2018) by discussing the heterogeneity of family principals, whose strategic choices depend on their reference points and preferences regarding SEW. Through CEO tenure, we identify the consequences of cognitive rigidity on FFP among long-tenured family CEOs. While cognitive rigidity has been discussed in terms of preventing family firms from adapting to environmental shifts (Chirico and Salvato, 2008) and impeding strategic renewal (Abdelgawad and Zahra, 2020), we extend this discussion by focusing on cognitive rigidity among family CEOs and its impact on FFP. Third, we contribute to generational theory (Mannheim, 1970) by focusing on the unique context of family firms. Our findings are consistent with the notion that Millennials are assuredly different (Anderson et al., 2017), an assertion equally applicable when considering Millennial family CEOs. This underscores the value of employing the core arguments of generational research (Edmunds and Turner, 2005; Gilleard, 2004; Mannheim, 1952) to gain deeper insights into the dynamics of family firms, thus moving beyond merely utilizing generations as a `constitutive concept’, which has been common in family firm research (Magrelli et al., 2022, p. 16). Finally, we provide insights for family firm owners and managers by demonstrating that, while the preference for perpetuating FCI will not harm FFP, investing in initiatives that enhance family members’ feelings of identification and belonging yields performance benefits. This is especially true for family firms led by Millennial CEOs and recently appointed family CEOs with low tenure, who make strategic decisions based more on identification logic. Accordingly, our results encourage family business owners to acknowledge both the advantages of Millennial family CEOs and the risks of overly extended CEO tenures, especially in succession scenarios.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

To investigate SEW in depth, Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía (2012) proposed five non-economic utility dimensions (FIBER): family control and influence (F), family members’ identification with the firm (I), binding social ties (B), emotional attachment (E), and renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession (R). Although all dimensions are crucial to family firms, Swab et al. (2020) argue that researchers should be intentional about which dimensions they examine. To this end, we provide clear arguments why we specifically direct our attention to FCI and FI. We focus on FCI and FI because family leaders have demonstrated the highest preference for these two SEW dimensions (Bauweraerts et al., 2022). Furthermore, we explore FCI as it has been identified as a necessary condition for SEW to exist (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero, 2022; Zellweger et al., 2012a), while FI is a highly salient SEW dimension (Gómez-Mejía, Cruz and Imperatore, 2014), with substantial influence that extends to both the internal and external environments of the family firm (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012).

Although both FCI and FI are considered dimensions of SEW, they differ in their foundations. FCI is a governance measure designed to represent actual family involvement (Gómez-Mejía and Herrero, 2022), which provides family principals with an ability to make strategic decisions and pursue both financial and non-financial goals (De Massis et al., 2014; Swab et al., 2020). FI represents more psychological aspects related to emotional and affective utilities and needs (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012) that impact the willingness and thus the motivation and attitudes that guide decision-making among family principals (De Massis et al., 2014). Hence, FCI provides family principals with the ability to make decisions, whereas the willingness to pursue decisions that are non-economic as opposed to economic often depends on FI.

Family control and influence and family firm performance

FCI refers to family members’ control and influence and specifically entails family owners’ desire to exercise control over strategic decisions (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012). The ability to control can be exerted directly by assuming important Top management team (TMT) and board positions, or indirectly by appointing key executives to the TMT or the board (Hülsbeck, Meoli and Vismara, 2019). Occupying such positions partly ensures that control rights over strategic decisions are maintained. Maintaining control can be the family's self-serving behaviour, undertaken as an instrumental path to preserving SEW (Zellweger et al., 2012a). Evidence suggests that maintaining control and influence is not always rooted in economic rationality, and may lead to financial costs (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011). Nevertheless, it provides potential benefits (Anderson and Reeb, 2003). In particular, FCI may lead to less divergence of interests between managers and stakeholders (Allouche et al., 2008; Anderson and Reeb, 2003), more efficient supervision of non-family executives (Anderson and Reeb, 2003; Chen, Cheng and Dai, 2013) and faster decision-making (Carney, 2005). However, several scholars conclude that the negative effects outweigh the positive (Swab et al., 2020).

Concerning the negative effects, Gao, Liu and Wang (2022) observed that the pursuit and preservation of SEW could lead to conflict and tension within the family, which could negatively affect performance. When appointing CEOs or board members, preserving SEW by maintaining FCI limits the benefits of choosing from a broad pool of potential resources. Family CEOs and family board members may be favoured over potentially more qualified non-family candidates within the external/internal labour market (Firfiray et al., 2018). This preference could result in unqualified management and a lack of talent (Cruz, Justo and De Castro, 2012; Dyer, 2006), ultimately impeding FFP.

- H1: A negative relationship exists between the degree of family control and influence and family firm performance.

Family identification with the firm and family firm performance

Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía (2012) suggest that FI is an essential dimension of SEW. It addresses a non-economic utility that families display strong preference for (Cennamo et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía, Cruz and Imperatore, 2014). For several reasons, we contend that FI positively influences FFP, although FI may not always have positive implications (Zellweger et al., 2012a).

Family members who value identification view the firm as a way to project their self-concept and self-esteem (Cennamo et al., 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). As such, FI causes family members to develop a strong feeling of belonging to the family business, regard the firm's success as their own, relate their social position to it, and attach a great deal of personal importance to the firm (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012). FI can translate into clear values and beliefs that capture what the family business stands for. This may drive greater efforts to enact agreements and attain the collective goals of the firm and its stakeholders (Bouncken et al., 2020). Additionally, FI can be an important source of motivation, serve as a non-monetary incentive for family members, and provide common ground to achieve excellent results (Sundaramurthy and Kreiner, 2008). These attributes prove hard to imitate, which gives rise to competitive advantages and wealth-creating performance (Habbershon, Williams and Macmillan, 2003). Moreover, family presence within the company may reinforce FI, making it a robust and long-lasting resource. However, FI can fade over time, particularly as the founding generation's involvement declines or control is passed on to non-family members (Cruz and Nordqvist, 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011).

- H2: A positive relationship exists between the degree of family members’ identification with the firm and family firm performance.

Moderating effect of CEO tenure

The theoretical foundation regarding the moderating effect of CEO tenure draws on such literature in general (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990; Hambrick and Fukutomi, 1991), while also relying on the specific family business strand (Boling, Pieper and Covin, 2016; Gómez-Mejía, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez, 2001; Martin, Campbell and Gómez-Mejía, 2014). CEO tenure, defined as the time a person has occupied the CEO position, is an observable CEO characteristic associated with distinctive patterns of CEO behaviour (Boling, Pieper and Covin, 2016; Miller and Shamsie, 2001). In this context, CEO behaviour and preferences change over the course of CEO tenure, and CEOs pass through different phases in their time in office, each with different organizational consequences (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990; Henderson, Miller and Hambrick, 2006). Over their tenure, some CEOs increase their commitment to their own strategic paradigms (Shen and Cannella, 2002), some grow stale and lose touch with the external surroundings (Henderson, Miller and Hambrick, 2006), and others start with a knowledge deficit and then steadily learn about their job (Finkelstein and Hambrick, 1990). Furthermore, over the course of their tenure, CEOs often solidify and enhance their power (Hambrick and Fukutomi, 1991). Given these dynamics, the impact of CEO tenure on firm performance unsurprisingly remains somewhat unclear. Some studies find no direct relationship (Huybrechts, Voordeckers and Lybaert, 2012; Simsek, 2007) and others suggest an inverted U-shape (Hambrick and Fukutomi, 1991; Henderson, Miller and Hambrick, 2006). Several maintain that CEOs enjoy longer tenures in family businesses (Berrone et al., 2010; Gómez-Mejía, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez, 2001). Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006) reveal that a family CEO average tenure ranges from 15 to 25 years, which is considerably shorter than in non-family firms. Accordingly, the primary justification for rewarding CEOs in family firms with extended tenures is the claim that they have been entrusted with protecting the stock of accumulated SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011; Martin, Campbell and Gómez-Mejía, 2014).

We argue that FCI negatively affects FFP and make the case that this negative relationship is stronger for long-tenured CEOs. Throughout their employment, CEOs’ authority often deepens, which results in their entrenchment (Finkelstein and D'aveni, 1994; Hambrick and Fukutomi, 1991). As such, when family CEOs pursue SEW goals and family objectives they often remain in their positions, solidifying their entrenchment and gaining more autonomy and power (Martin, Campbell and Gómez-Mejía, 2014). In this context, a family CEO's strong relationship with the board of directors, which often deepens throughout their tenure, may diminish the efficacy of monitoring, lead to inaccurate assessments of the CEO's decision-making skills, and reduce the likelihood of the business strategy being examined and challenged (Gómez-Mejía, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez, 2001). Considering that highly family-controlled firms tend to pursue non-economically motivated undertakings and suboptimal business strategies, the presence of a long-tenured CEO (often associated with an ineffective board of directors and less pressure to pursue economic objectives) is likely to amplify the negative effects of FCI on FFP.

- H3a: The negative relationship between family control and influence and family firm performance is stronger in family firms with long-tenured CEOs.

We argue that FI positively influences family firms’ performance. We contend that the amount of time a CEO spends in office modifies the cause-and-effect relationship between FI and FFP. Recently appointed family CEOs are often driven to enhance performance (Cirillo et al., 2021), while demonstrating willingness to enforce strategic change (Kellermanns et al., 2008) and adopt relatively risky strategic postures (Zahra, 2005). However, their abilities to implement such strategies are often constrained by limited firm knowledge (Boling, Pieper and Covin, 2016) and cognitive constraints (Gómez-Mejía, Larraza-Kintana and Makri, 2003). Facing these challenges, they see a need to attain knowledge and support from other family members, thus showing great willingness to involve and use them (Cirillo et al., 2021). Under these circumstances, FI (providing a strong stimulus to contribute to the firm) reinforces family members’ motivation and commitment to actively support the CEO. In other words, synergies exist between having a newly appointed family CEO and FI. We posit that these synergies have potentially favourable consequences for FFP.

- H3b: The positive relationship between family identification and family firm performance is weaker in family firms with long-tenured CEOs.

Moderating effect of Millennial CEOs

The generational cohorts to which family CEOs belong have been widely overlooked in the family business debate (Cirillo et al., 2022; Magrelli et al., 2022). Therefore, we examine what happens to the SEW components–FFP relationship when accounting for the leadership priorities of family CEOs from the Millennial generation (borne between 1982 and 1999). We adopt generational theory as the theoretical framework, which holds that historical and social life experiences impact how people from different generations develop unique values and personalities (Edmunds and Turner, 2005; Gilleard, 2004; Mannheim, 1952). A key premise of this theory is that these values and personalities result in predictable behaviours that are also visible in a professional setting; consequently, generational differences have organizational consequences (Kupperschmidt, 2000; Parry and Urwin, 2011; Twenge et al., 2010). Furthermore, to explore different generations, well-defined generational cohorts reflecting groups of individuals born in the same period of time have been established (Parry and Urwin, 2011). Most research exploring generational cohorts directs its attention towards the broader workforce as the primary unit of analysis (Smola and Sutton, 2002; Twenge et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2008). However, a subset of studies examine CEOs and executive leaders more specifically (Arslan et al., 2022; Cirillo et al., 2022; Tee et al., 2021). This line of research maintains the significance of considering the generational cohorts to which CEOs belong, given that executive leaders exhibit distinctive traits associated with their generation. Here, CEOs may possess distinctive traits influenced by varying exposures during their formative life to globalization, information technologies, economic contexts and socialization (Chen, Chittoor and Vissa, 2015; Yeoh and Hooy, 2022). These exposures influence CEO leadership styles and decision-making practices, leading to variations in risk taking (Yeoh and Hooy, 2022), levels of internationalization (Cirillo et al., 2022) and the meaningfulness of entrepreneurship (Arslan et al., 2022). Focusing on Millennials, we explore the most recent cohort of individuals occupying managerial positions. This generational cohort is proficient in digital technologies, highly educated, team-oriented, adept at navigating social networks and committed to social responsibility (Howe and Strauss, 2000; Liu et al., 2019). They have core values that demonstrate confidence, optimism, civil duty, achievement, morality and appreciation of diversity (Zabel et al., 2017). Millennial leaders therefore bring an energizing presence (Sessa et al., 2007) while being open and proactive, which fosters a commitment to exploit new opportunities and change their businesses (Arslan et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2019). Moreover, Millennials are often characterized by negative qualities (Galdames and Guihen, 2022). Specifically, they have been labelled as fragile, individualistic, intolerant and demanding (Hershatter and Epstein, 2010; Myers and Sadaghiani, 2010). In their roles as leaders, they tend to display less long-term commitment to organizations, which affects their desire to stay with a firm (Arslan et al., 2022; Tee et al., 2021). Some suggest that their leadership style is influenced by their relatively lower preferences for honesty and loyalty (Rudolph, Rauvola and Zacher, 2018; Sessa et al., 2007), which results in them being questioned for hidden motives and perceived lack of trustworthiness (Galdames and Guihen, 2022).

Accordingly, we posit that the negative relationship between FCI and FFP is strengthened when the CEO belongs to the Millennial generational cohort for several reasons. Millennial CEOs tend to be less devoted and committed to the company they work for (Galdames and Guihen, 2022; Tee et al., 2021). Additionally, they value individual achievement and success to a larger extent than providing benefits to their organization (Rudolph, Rauvola and Zacher, 2018). Therefore, in family firms, we expect Millennial CEOs to exhibit less commitment to the business family and to appraise their goals to a lesser extent. Considering that highly controlled family firms are likely to be more successful when high-quality relationships built on mutual understanding develop between the CEO and the owning family (Blumentritt, Keyt and Astrachan, 2007), a family CEO who is neither committed to family priorities nor aligned with their goals is unlikely to be a sustainable recipe. Under such conditions, personal disagreements and conflicts of negative nature could develop, which may consequently harm FFP (Kellermanns and Eddleston, 2007). Therefore, a Millennial CEO may exacerbate the detrimental effects of FCI on performance.

- H4a: The negative relationship between family control and influence and family firm performance is stronger in family firms with Millennial CEOs.

Research suggests that FI provides family firms with a competitive advantage (Sundaramurthy and Kreiner, 2008; Zellweger, Eddleston and Kellermanns, 2010). Although this may be the case, understanding under what conditions the relationship between FI and FFP is strong/weak is interesting. Here, we argue that the positive impact of FI on FFP is weaker for family firms managed by Millennial CEOs.

Methods

Data collection

To test our hypotheses, we use a sample of 1833 family firms. Data come from the global family business survey conducted by the STEP Project Global Consortium4 (SPGC) between 2018 and 2019. SPGC is an independent consortium of academic institutions around the world aiming at exploring family businesses’ successful transgenerational entrepreneurship practices and it leads context-sensitive applied research initiatives with the goal of examining such practices.

Data were collected through a survey project developed in collaboration with 48 universities that launched common online questionnaires in their respective countries between 2018 and 2019. The questionnaire was first developed in English and then translated into 17 languages using a professional translation service. The questionnaire validation process was strengthened by a critical analysis by researchers with experience in conducting qualitative and quantitative research. It was then pre-tested to minimize consistency artifacts, modify ambiguous, vague and unclear questions and exclude erroneous indicators (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Respondents are typically senior family business leaders with an overall strategic overview and effective ownership control of their company. In total, 1833 responses were received from 33 countries (response rate = 37%).

The locations of observations in our sample are listed in Table 1. Roughly 40% come from Europe and Central Asia, 13% from North America, 21% from Latin America and the Caribbean, 20% from Asia and the Pacific, and 6% from the Middle East and Africa. In terms of size, 30% have fewer than 20 employees, 34% between 21 and 100, 27% between 101 and 1000, and 9% more than 1000. By industry, 57% of the family businesses operate in services such as transportation, finance, retail and wholesaling, 30% belong to manufacturing industries, and the remaining 13% operate in agriculture and mining.

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Australia (1.5) | Japan (4.2) |

| Belgium (1.4) | Mexico (2.9) |

| Brazil (3.8) | Netherlands (1.9) |

| Chile (2.2) | Peru (1.5) |

| China (2.0) | Philippines (1.4) |

| Colombia (5.6) | Portugal (2.2) |

| Costa Rica (3.9) | Russian federation (1.6) |

| Ecuador (2.3) | Saudi Arabia (1.6) |

| Finland (2.7) | South Africa (6.4) |

| France (2.6) | Spain (2.0) |

| Germany (1.5) | Taiwan (2.3) |

| Guatemala (1.9) | Thailand (2.8) |

| Hong Kong (SAR) (5.6) | Turkey (2.7) |

| Hungary (3.0) | United Arab Emirates (1.9) |

| India (1.5) | United Kingdom (10.5) |

| Ireland (7.3) | Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of (3.6) |

| Italy (1.9) | |

- Note: Percentage of responses from each country are in parentheses.

Variables

Dependent variable. Family firm performance (FFP) was measured using a 7-item construct adapted from Eddleston, Kellermanns and Sarathy (2008) regarding sales, returns and profitability in relation to competitors. Respondents were asked about their current firm performance compared with their competitors through the use of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from `strongly disagree’ to `strongly agree’. Specifically, respondents were asked to rate the following with respect to their main competitors: (1) growth in sales, (2) growth in market share, (3) growth in number of employees, (4) growth in profitability, (5) return on equity, (6) return on asset and (7) profit margin. Individual performance indicators were then added to obtain an overall score via principal component analysis. All factor loadings were above 0.7 and produced a single construct with a Cronbach's α > 0.9. Additionally, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to check the reliability and robustness of our measurements. The validity of our performance measurement was confirmed, with an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.63, exceeding the recommended value of 0.50, and a composite reliability (CR) of 0.92, higher than the critical threshold of 0.70.

Independent variables. The first independent variable is family control and influence (FCI) considered as one component of SEW, measured using a 6-item construct adapted from Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía (2012). The questionnaire asked respondents the extent to which they agreed with the following items [measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)] for their family firm: (1) the majority of the shares in the family business are owned by family members, (2) family members exert control over the company's strategic decisions, (3) most executive positions are occupied by family members, (4) non-family managers and directors are named by family members, (5) the board of directors is mainly composed of family members, (6) preservation of family control and independence are important goals for my family business. The answers were combined to form a single construct with a Cronbach's α = 0.87, which indicates good reliability. Additionally, a CFA confirmed the validity of our measurement with an AVE and CR equal to 0.56 and 0.88, respectively. The second independent variable is family members’ identification with the firm (FI), measured using a 5-item construct (measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from `strongly disagree’ to `strongly agree’) adapted from Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía (2012). Respondents were asked to what extent: (1) family members have a strong sense of belonging to the family business, (2) family members feel that the family business’ success is their own, (3) their family business has a great deal of personal meaning for family members, (4) being a member of the family business helps define who they are, (5) family members are proud to tell others that they are part of the family business. The individual items were added to form an overall score with a Cronbach's α of 0.92. The AVE and CR were 0.72 and 0.93, respectively.

Moderators. Both moderators specifically explore characteristics of family CEOs. First, CEO tenure was measured by asking respondents `how many years the current CEO has been employed by the family business’ (Glowka, Kallmünzer and Zehrer, 2020; Meier and Schier, 2021). The answers were grouped in year range from `1–5’ to `41 or more’. Second, CEO Millennials is a dichotomous variable and measures the generational cohort of the current CEO of the family firm. We operationalized this variable as a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if the CEO belongs to the Millennial generational cohort (‘Millennials’ born in 1982–1999) (Gray et al., 2019; Twenge et al., 2010), and of 0 if the CEO belongs to another generational cohort (`Silent generation’, `Baby boomers’ or `Generation X’). Table 2 reports the descriptive information of the CEO cohorts.

| CEO generational cohort | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Silent generation | 126 | 6.87 |

| Baby boomers | 906 | 49.43 |

| Generation X | 482 | 26.3 |

| Millennials | 319 | 17.4 |

| Total | 1,833 | 100 |

Controls. To control for alternative explanations, we include a wide range of control variables. The first set refers to the family CEO. First, CEO education was measured by considering the highest level of education completed by the current CEO. The questionnaire asked respondents to ‘indicate the highest level of education completed’, from ‘no formal schooling’ to ‘doctorate’. CEO education may influence decision-making and eventually performance (Mahto et al., 2010) but may also be related to SEW considerations (Classen et al., 2012). CEO only child is a dichotomous variable adapted from Calabrò et al. (2018) that takes the value of 1 if the current CEO is an only child and of 0 if they have siblings. We obtained this information from the questionnaire and include it as it may impact family dynamics and, consequently, SEW (Calabrò et al., 2018). CEO gender is a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 when the family firm is led by a female CEO, and of 0 in the case of a male CEO. The variable may relate to SEW (Baixauli-Soler, Belda-Ruiz and Sánchez-Marín, 2021) and FFP (Amore, Garofalo and Minichilli, 2014). A second set of controls refers to the family firm. Firm size was measured by considering the number of full-time employees. From the questionnaire, we have 11 classes of full-time employees in four groups from `below 20’ to `more than 1000 employees’. Firm size is included as it is considered relevant to SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011) and performance (Zellweger et al., 2012a). To control for industry characteristics, we used a categorical variable that takes the value of 1 in the case of `agriculture and mining’, 2 for `manufacturing’ and 3 for `service’. We included it as it may relate to SEW (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012) and performance (Naldi et al., 2013). We then controlled for the governance mechanism and distinguished between family and corporate. Specifically, family governance mechanism measures the amount of family business governance structures and policies adopted by the family business (i.e. formal family council, family assembly, formal family meetings, family protocol or constitutions, family employment policy, mandatory retirement age for family). Family governance mechanisms may relate to FCI (Klein, Astrachan and Smyrnios, 2005), SEW in general (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011) and FFP (Azila-Gbettor et al., 2018). Corporate governance mechanism measures the number of corporate governance structures or policies adopted (i.e. board of advisors, formal board of directors, external directors on the board, different share classes, formal succession process, women on the board). The variable is relevant to SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011) and FFP (Azila-Gbettor et al., 2018). Generation dispersion was measured by considering if one or multiple generations are involved in the firm. The variable takes the value of 1 if more than one generation is involved and of 0 if there is only one generation. Generation dispersion may also influence the importance of SEW (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011; Kellermanns et al., 2008). Finally, a third set of control variables refers to the home country. Specifically, we controlled for market dynamism as it may influence FFP (Chen et al., 2016). Our measure is based on an adaptation of Jaworski and Kohli's (1993) market dynamism scale, which we adapted to explicitly capture market dynamism in terms of change and heterogeneity in the market. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: (1) changes in the market are intense, (2) clients regularly ask for new products and services, (3) changes are taking place continuously, (4) in a year, nothing has changed in the market, and (5) the volumes of products and services to be delivered change fast and often. These items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Market dynamism was operationalized as the average of the five items. The Cronbach's α for the final variable was 0.75. Regarding the home country, we introduce the dummy variable Home Europe to control for the high number of respondents from Europe, GDP per capita (log value) and institutional quality. We measure institutional quality using the World Governance Indicators (WGI) indicators (WGI, 2019). Specifically, we use the mean value of six specific items (1 year lagged): voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption. These variables account for the likely effects of cultural and institutional differences (Campopiano, Calabrò and Basco, 2020).

Estimations

We applied ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with moderator effects using the bootstrapping approach. Following Hayes (2013), bootstrapping is considered the most reliable approach for testing moderation effects. We resampled our data 5000 times. Before conducting our analysis, we checked for multicollinearity. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix and summary statistics for the variables. Following Mela and Kopalle (2002), we take 0.7 as a threshold for the harmful effect of multicollinearity. The correlation matrix reveals a weak correlation among our variables; the highest pair-wise correlation is between FCI and FI, but it does not exceed the threshold value. The dataset does not suffer from multicollinearity issues. However, we double-checked for multicollinearity by running the variance inflation factor (VIF), which reveals that each variable is below the critical threshold of 10 (O'Brien, 2007), and the tolerance rate does not fall below 0.1 (Hair et al., 2006).

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family firm performance | 3.50 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. Family members identification with the firm | 3.81 | 1.08 | 0.08*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. Family control and influence | 3.77 | 1.08 | −0.00 | 0.70*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. CEO tenure | 4.58 | 2.35 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. CEO Millennials | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.546*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. CEO education | 6.34 | 1.97 | 0.06*** | −0.09*** | −0.11*** | −0.18*** | 0.10*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. CEO only child | 0.06 | 0.24 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.04* | −0.09*** | 0.09*** | −0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. CEO gender | 0.18 | 0.38 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.16*** | 0.08*** | −0.01 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| 9. Firm size | 2.16 | 0.95 | 0.16*** | 0.00 | −0.11*** | −0.14*** | −0.07** | 0.16*** | −0.01 | −0.17*** | 1.00 | ||

| 10. Industry | 2.44 | 0.70 | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.10*** | 0.02 | 0.04* | 0.01 | 0.07*** | −0.08*** | 1.00 | |

| 11. Family governance mechanism | 2.36 | 1.81 | 0.15*** | 0.04* | −0.05** | 0.06** | −0.04*** | 0.08*** | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.24*** | −0.07*** | 1.00 |

| 12. Corporate governance mechanism | 2.11 | 1.43 | 0.12*** | 0.01 | −0.11*** | 0.08*** | −0.07*** | 0.12*** | −0.04* | −0.03 | 0.32*** | −0.07*** | 0.53*** |

| 13. Generation dispersion | 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.00 | 0.07*** | 0.04* | 0.03 | 0.13*** | 0.18*** | −0.05** | −0.02 | 0.23*** | −0.11*** | 0.09*** |

| 14. Market dynamism | 3.29 | 0.65 | 0.06*** | 0.19*** | 0.10*** | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.05** | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04* | 0.00 | 0.07*** |

| 15. Home Europe | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | 0.04* | −0.06** | −0.25*** | 0.07*** | 0.05** | −0.14*** | 0.03* | −0.05** |

| 16. GDP per capita | 10.26 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 0.06*** | 0.08*** | 0.11*** | −0.03* | −0.07*** | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07* | −0.10* |

| 17. Institutional quality | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.18*** | −0.08*** | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.08*** | 0.12*** | 0.02 | −0.06*** |

| Variables | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |||||||

| 12. Corporate governance mechanism | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 13. Generation dispersion | 0.13*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 14. Market dynamism | 0.09*** | −0.04* | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 15. Home Europe | −0.05** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 16. GDP per capita | −0.05* | 0.07*** | −0.00 | 0.34*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 17. Institutional quality | −0.01 | 0.15*** | −0.04 | 0.26*** | −0.30*** | 1.00 |

- Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively.

Results

The results of the regression models with moderating effects are as follows: in Table 4, Model 1 displays only the control variables; Models 2 and 3 contain the full model with the two independent variables separately; Model 4 reports the full model; Models 5–8 report the full model with the moderating terms, that is, CEO tenure and CEO Millennials.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

| H1: FCI | 0.012 | −0.060** | −0.030 | −0.058** | −0.067** | −0.062** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.026) | (0.041) | (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |||

| H2: FI | 0.058*** | 0.101*** | 0.102*** | 0.175*** | 0.101*** | 0.085*** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.041) | (0.026) | (0.027) | |||

| CEO tenure | −0.013 | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.012 | 0.013 | 0.051* | −0.012 | −0.013 |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| CEO Millennials | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.075 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 0.084 | −0.068 | −0.285 |

| (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.179) | (0.175) | |

| CEO education | 0.024** | 0.024** | 0.026** | 0.025** | 0.025** | 0.024** | 0.025** | 0.024** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| CEO only child | −0.042 | −0.040 | −0.037 | −0.044 | −0.040 | −0.035 | −0.041 | −0.036 |

| (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.076) | (0.075) | (0.076) | (0.075) | (0.076) | (0.075) | |

| CEO gender | −0.013 | −0.013 | −0.013 | −0.013 | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.013 | −0.012 |

| (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.049) | |

| Firm size | 0.135*** | 0.136*** | 0.134*** | 0.130*** | 0.129*** | 0.130*** | 0.129*** | 0.130*** |

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| Industry | ||||||||

| 2 | −0.034 | −0.034 | −0.030 | −0.029 | −0.032 | −0.038 | −0.030 | −0.032 |

| (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | |

| 3 | −0.012 | −0.013 | −0.014 | −0.011 | −0.014 | −0.019 | −0.013 | −0.017 |

| (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.058) | |

| Family governance mechanism | 0.045*** | 0.045*** | 0.044*** | 0.043*** | 0.043*** | 0.043*** | 0.043*** | 0.043*** |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.012) | |

| Corporate governance mechanism | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| Generation dispersion | −0.130*** | −0.132*** | −0.141*** | −0.140*** | −0.140*** | −0.143*** | −0.141*** | −0.141*** |

| (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | |

| Market dynamism | 0.056* | 0.055* | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.039 |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Home Europe | 0.503 | 0.510 | 0.543 | 0.537 | −0.045 | −0.279 | 0.139 | 0.354 |

| (0.610) | (0.610) | (0.608) | (0.608) | (3.878) | (3.874) | (3.879) | (3.876) | |

| GDP per capita | 0.501 | 0.499 | 0.468 | 0.451 | 0.674*** | 0.661*** | 0.671*** | 0.650*** |

| (0.377) | (0.378) | (0.377) | (0.376) | (0.247) | (0.247) | (0.247) | (0.247) | |

| Institutional quality | −0.258 | −0.265 | −0.259 | −0.223 | −0.351 | −0.231 | −0.440 | −0.535 |

| (0.530) | (0.531) | (0.529) | (0.529) | (1.926) | (1.925) | (1.927) | (1.925) | |

| H3a: FCI*CEO tenure | −0.007 | |||||||

| (0.007) | ||||||||

| H3b: FI*CEO tenure | −0.016** | |||||||

| (0.007) | ||||||||

| H4a: FCI*CEO Millennials | 0.039 | |||||||

| (0.045) | ||||||||

| H4b: FI*CEO Millennials | 0.096** | |||||||

| (0.044) | ||||||||

| Country fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −2.365 | −2.399 | −2.264 | −2.015 | −4.001 | −3.843 | −3.964 | −3.867 |

| (3.725) | (3.726) | (3.715) | (3.712) | (3.610) | (3.606) | (3.611) | (3.606) | |

| Observations | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 | 1833 |

| R-squared | 0.124 | 0.124 | 0.129 | 0.132 | 0.132 | 0.134 | 0.132 | 0.134 |

- Note: *,** and *** denote significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% level, respectively. Standard errors are in parentheses.

Regarding H1, we predict a negative relationship between FCI and the FFP. As reported in Table 4 Model 2, the coefficient of the FCI is positive and not significant; H1 is not supported. H2 predicts a positive effect of FI on FFP. As Model 3 shows, the corresponding coefficient is positive and statistically significant with a p-value below 1%. An increase of one point in FI increases FFP by 5.8% on average. Thus, H2 is fully supported with a marginal economic significance. Moreover, when FCI and FI are regressed on FFP in the same model (Model 4), both are significant and in line with our predictions.

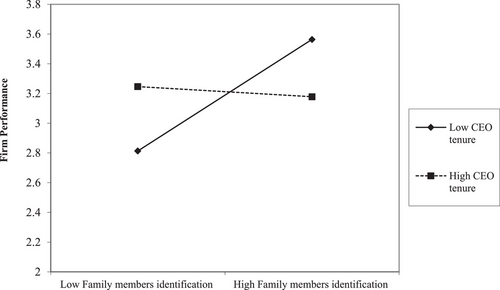

The moderating effects of CEO tenure and CEO Millennials are analysed in Models 5–8. H3a predicts that the negative relationship between FCI and FFP is stronger in family firms with long-tenured CEOs. In Model 5, the coefficient of the moderation is negative but not significant; H3a is not confirmed. H3b predicts that the positive relationship between FI and FFP is weakened by CEO tenure. The corresponding coefficient in Model 6 is negative and significant, with a p-value below 5% and marginal economic significance, which supports H3b. We plotted the interaction effect and conducted simple slope tests to check the statistical significance of the slopes and between points (Aiken, West and Reno, 1991). According to Figure 2, for a low value of CEO tenure, the simple slope is 0.188 and significantly different from zero at a p-value < 0.01. In the case of high CEO tenure, the simple slope is negative but not significant. This means that a higher FFP is associated with high FI and this effect is stronger with a lower CEO tenure, although we do not find any statistical support for higher tenure. We also performed a marginal effect analysis to measure the moderating effect on FFP. Specifically, at high levels of CEO tenure (70th and 90th percentiles), FI reduces the FFP with 2.7% (dy/dx = −0.0276; 95% CI = [−0.048, −0.007]) and 3.5% (dy/dx = −0.0350; 95% CI = [−0.0593, −0.0108]), respectively.

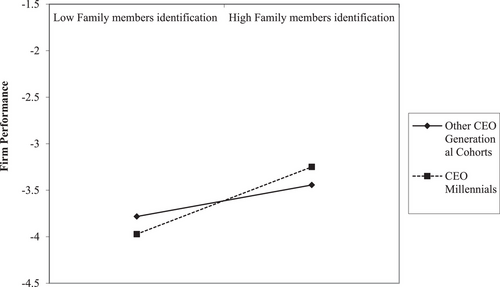

H4a and H4b investigate the moderating effect of Millennial CEOs on the main relationships. Specifically, H4a posits that the negative relationship between FCI and FFP is stronger in family firms with CEOs belonging to a Millennial generational cohort. The corresponding coefficient in Model 7 is positive and not significant; H4a is not confirmed. H4b examines the moderating effect of Millennial CEOs on the relationship between FI and FFP. More specifically, we predict that the positive relationship between FI and FFP is weaker in family firms with CEOs belonging to a Millennial generational cohort. The corresponding coefficient in Model 8 is positive and significant with a p-value below 5% and marginal economic significance; H4b is not supported. Again, we plot our results to facilitate interpretation (Aiken, West and Reno, 1991). The plot in Figure 3 indicates that in the case of other generational cohorts, the simple slope is 0.085 and significantly different from zero at the p-value <0.01; for Millennials, the simple slope is 0.180 and significantly different from zero at the p-value <0.01. This means that higher FFP is associated with higher FI, and this effect is stronger for family CEOs belonging to a Millennial cohort. Specifically, in the case of a CEO from a Millennial generational cohort, a higher level of FI with the firm (70th and 90th percentile) increases FFP with 15.56% (dy/dx = 0.1556; 95% CI = [0.026, 0.284]) and 19.40% (dy/dx = 0.1940; 95% CI = [0.043, 0.344]), respectively. Furthermore, robustness checks and additional evidence are provided5.

Family members’ identification with the firm and family firm performance: moderating effect of Millennial CEO.

Discussion and conclusion

By integrating arguments from the SEW and CEO tenure literature and generational theory, we explored the impact of the FCI and FI components of SEW on FFP. Moreover, we investigated the moderating effects of CEO tenure and Millennial CEOs on this relationship. We predicted that while FCI would have a negative impact on FFP, FI would have a positive impact. Moreover, we argued that the negative effect of FCI on performance would be stronger for long-tenured CEOs and that the positive effect of FI on performance would be weaker for long-tenured family CEOs. Finally, we predicted that while the negative effect of FCI on performance would be stronger in family firms with family CEOs from the Millennial generational cohort, the positive effect of FI on performance would be weaker for Millennial CEOs.

The results extend our understanding on the dark and bright sides of SEW (Samara et al., 2018; Temouri et al., 2022). We specifically operationalized Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía's (2012) SEW dimensions of FCI and FI and discovered no dark sides associated with SEW. This discovery has crucial implications, particularly in the context of family firm decision-making. In contrast to the decision dilemma proposed by Gómez-Mejía, Patel and Zellweger (2015), where the potential advantages of FCI should be weighed against its possible negative impact on FFP, our research reveals that no such tradeoff exists. However, our analysis suggests that FI represents the more distinct bright side of SEW, offering great utility through its positive influence on FFP.

By integrating CEO tenure as a moderating variable, we find that CEO tenure does not moderate the relationship between FCI and FFP (H3a). This indicates that the negative aspects of a long-tenured and entrenched CEO, such as their increasing devotion to their own paradigms, use of fewer external cues and resources (Gómez-Mejía, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez, 2001), as well as their discouragement of qualified non-family executives (Samara et al., 2018), does not strengthen the negative impact that FCI has on FFP.

We find that CEO tenure weakens the relationship between FI and FFP (H3b). This implies that long-tenured CEOs develop cognitive rigidity and resistance to change, thereby weakening the positive impact that FI has on FFP. This finding has important implications for how family firms employ strategies to ensure longevity (Zellweger, Nason and Nordqvist, 2012b). In contrast to the perspective that longevity is ensured through conservation strategies, where family legacy is maintained through dominant family principals (Bertrand and Schoar, 2006; Miller et al., 2007), our research favours a more adaptive approach that embraces strategic renewal as a means to ensure longevity (Abdelgawad and Zahra, 2020). This can be achieved by appointing a new family CEO who is less inclined to resist strategic renewal. We contend that this fosters a stronger FI–FFP relationship.

We also predicted that Millennial CEOs would impact the FCI–FFP relationship (H4a). Although, we did not find support for this hypothesis, this indicates that family CEOs belonging to different generational cohorts do not have distinctive values and behaviours that significantly alter the relationship between FCI and FFP. Finally, we find that the FI–FFP relationship is stronger in family firms with Millennial CEOs. These findings bring new nuances to recent research exploring the positive attributes of family CEOs from the Millennial generational cohort (Cirillo et al., 2022). Although Millennial leaders have been characterized as being more individualistic, less committed to their organizations and attaching less value to the belongingness of social groups at work (Tee et al., 2021), these characteristics do not seem to have negative consequences for how family CEOs of these generations impact the FI–FFP relationship. However, their strong interest in accommodating the family (Sessa et al., 2007; Twenge et al., 2010) may make the family business an integral part of these CEOs’ identity and emotions. This sense of purpose may transfer into increased effort and dedication to the company's success, thus improving its performance.

Implications for theory

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, our research adds more evidence and clarity to the consideration of SEW as an antecedent of FFP (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012). Our analysis reveals that not all decisions aimed at maximizing SEW will lead to performance losses, thus moving beyond the core argument that non-economic and economic goals are inversely related (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016; Swab et al., 2020). Moreover, we extend the research on performance advantages of SEW (Cruz, Gómez-Mejia and Becerra, 2010) by revealing that FI has performance benefits. In doing so, we clarify that FI, the SEW dimension representing psychological aspects related to emotions and affective utilities, has positive performance consequences. Conversely, FCI, a governance measure reflecting family involvement and providing family principals with an ability, does not exert a direct impact in contrast to the previous literature (Martin and Gómez-Mejía, 2016). Therefore, this study exposes FCI to inconsistencies, which is a contribution in itself (Makadok, Burton and Barney, 2018). This addresses the debate regarding the role of different dimensions of SEW, and their fundamentally different foundations, as drivers of strategic choices that impact performance in family firms (De Massis et al., 2014; Gómez-Mejía and Herrero, 2022; Swab et al., 2020).

Second, we consider SEW as a theory about family principals’ reference points and preferences (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2011), thus contributing to making SEW a `homegrown’ theory within family business research (Hasenzagl, Hatak and Frank, 2018; Jiang et al., 2017). Here, we discuss and explore the heterogeneity among family principals through the role played by specific characteristics of family CEOs, whose strategic choices alter the nature of the SEW–FFP relationship. Hence, we address calls to incorporate a CEO perspective into the investigation of SEW dimensions and FFP (Minichilli et al., 2014). Specifically, we explore how family CEO tenure interacts with SEW to impact FFP. Our findings are consistent with Henderson, Miller and Hambrick's (2006) suggestion that CEO tenure has a significant role in explaining performance variations. Moreover, our study resonates with family firm-specific research, which reports negative consequences associated with long-tenured CEOs of family firms (Boling, Pieper and Covin, 2016; Kellermanns et al., 2008). However, by exploring the tenure of family CEOs specifically as opposed to that of non-family CEOs, we introduce a key dimension of family governance, thus shedding light on a nuanced factor that explains family firm heterogeneity (Chua et al., 2012).

Third, by examining CEO generational cohorts more precisely, we demonstrate that family CEOs of different generations make strategic choices with different reference points, which alters the nature of the SEW–family firm performance relationship. Utilizing Mannheim's generational theory (Mannheim, 1970), we address scholarly calls to employ key theoretical arguments that are founded in generational research (Magrelli et al., 2022). Our findings confirm that family CEOs of the distinct Millennial generational cohort have been influenced by societal and economic events, leading to comparatively similar behaviours and values that are also visible in a family firm setting (Cirillo et al., 2022). These advancements call for family business scholars to carefully consider theories from related disciplines, such as psychology and sociology, to better understand family firms.

Implications for practice

Our study offers several insights for family business practitioners and owners. We provide a deeper understanding of the performance consequences of two of family firms’ main priorities. Specifically, we document that the preference for perpetuating FCI has no performance consequences, while the creation of a strong sense of belonging to and identification with the firm pays off better in terms of performance. Moreover, CEO tenure should be monitored as it has performance effects, especially when it causes a long-tenured family CEOs to be increasingly rigid and resistant to change, thus reducing the positive aspects of FI. In such a situation, it may be better to succeed that CEO. Although we do not identify any positive performance consequences of a long-tenured family CEO, careful reflections on the consequences of succeeding a long-tenured family CEO are essential. Family owners should keep in mind that family CEOs from different generations have different leadership behaviours and priorities. Considering that many family businesses are leaving space for Millennials at an increasing rate (Cirillo et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2019), understanding the performance consequences of employing such CEOs is important. Specifically, our results indicate that Millennial CEOs strengthen the positive impact of FI on FFP. This can be a stimulus for family business owners who themselves may be part of an older generation to pay attention to the potential positive attributes of the most recent generation reaching managerial ranks, especially in situations of succession.

Limitations and future research

Our study has some limitations, which offer several opportunities for future research. Following previous studies such as Astrachan and Shanker (2003), we investigated only two of the five dimensions of the FIBER construct (Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía, 2012). Although Swab et al. (2020) argue that the SEW dimensions should be chosen intentionally, future research could explore the other three conceptualized dimensions. To this end, we need to understand their impact on FFP. As Berrone, Cruz and Gómez-Mejía (2012) suggest, this line of research could also examine which combination of the five dimensions has the most favourable or unfavourable impact on FFP.

Considering the positive attributes of Millennial family CEOs, future research should investigate the distinctive challenges and success criteria associated with succeeding power and leadership to this generational cohort, bearing in mind that a substantial number of future family firm successors will belong to this cohort. Such research could apply generational theory to enrich a field that has predominantly treated generations as a constitutive concept, frequently exploring generational stages, involvement or relationships, while lagging in the exploration of generations from a societal cohort-based perspective (Magrelli et al., 2022).

We did not consider the possibility of survivorship bias in our sample, which occurs when the sample of family businesses used in empirical studies favours established and successful businesses over all other family businesses (Anderson et al., 2022). In fact, studies tend to ignore failing or market-exiting businesses and instead concentrate on successful ones that have endured over time. The possibility that poorly performing family-owned businesses may no longer be included in the sample could result in an overestimation of their performance, which could lead to an overestimation of family business success and inaccurate conclusions regarding the benefits of family ownership (Baek and Cho, 2017; Cruz et al., 2014). Future research could broaden the sample to include a wider range of family businesses, including those that have failed or left the market, or account for enterprises excluded from the sample to compensate for survivorship bias. Additionally, future research could test our theoretical framework using objective performance data when addressing these issues.

Biographies

Carl Åberg is an Associate Professor at the Department of Business, Strategy and Political Sciences at the University of South-Eastern Norway. He completed his PhD at the Chair of Management and Corporate Governance at Witten/Herdecke University. His research interests are in the areas of corporate governance, boards of directors, family firms, ventures and dynamic capabilities.

Andrea Calabrò is Professor of Family Business and Entrepreneurship at IPAG Business School (France). He is the Academic Director of the STEP (Successful Transgenerational Entrepreneurship Practices) project. He co-founded the Family Business Research Strategic Interest Group (FBR SIG) at the EURAM and is co-founder and organizer of the International Family Business Research Forum (IFBRF). His research interest regards family firms, internationalization and corporate governance.

Alfredo Valentino is an Associate Professor in International Business at ESCE International Business School in Paris. He obtained his PhD in Management from Luiss Guido Carli University in Italy. He is currently a Global Research Champion of the STEP Project Global Consortium. His research interests include family firm internationalization, headquarter–subsidiary relations, location and relocation decisions of multinational enterprises, and the internal and external embeddedness of subsidiaries.

Mariateresa Torchia is Director of Research and Faculty Development, Full Professor of Strategic Management, Director of the Doctorate in Business Administration at the International University of Monaco. She serves as associate editor for Journal of Business Research in the area of strategy and family firms. She holds a PhD in Management and Governance from the University of Rome “Tor Vergata”. She has published journal articles on corporate governance, gender diversity, and family firms in leading international peer-reviewed journals such as: Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Business Ethics, International Business Review, European Management Journal, Organizational Dynamics, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Journal of Small Business Management, Journal of Management and Governance, Strategic Change, Small Business Economics, Public Management Review, etc.

References

- 1 FIBER consist of five non-economic utility dimensions that represent the SEW priorities of family firms: Family control and influence, Identification of family members with the firm, Binding social ties, Emotional attachment of family members, and Renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession (Berrone et al., 2012).

- 2 `Family CEOs’ are individuals with family bonds to the owning family; this is as opposed to `non-family CEOs’, who are hired professionals from outside of the family. All CEOs in our sample are family CEOs.

- 3 For more information on the STEP Project Global Consortium please visit this page: https://spgcfb.org/

- 4 For more information, see the website of SPGC: https://spgcfb.org/

- 5 Found in online-only Supporting Information at the end of the paper.