Constructing Spaces for Strategic Work: A Multimodal Perspective

Abstract

In this paper we take seriously the call for strategy-as-practice research to address the material, spatial and bodily aspects of strategic work. Drawing on a video-ethnographic study of strategic episodes in a financial trading context, we develop a conceptual framework that elaborates on strategic work as socially accomplished within particular spaces that are constructed through different orchestrations of material, bodily and discursive resources. Building on the findings, our study identifies three types of strategic work – private work, collaborative work and negotiating work – that are accomplished within three distinct spaces that are constructed through multimodal constellations of semiotic resources. We show that these spaces, and the activities performed within them, are continuously shifting in ways that enable and constrain the particular outcomes of a strategic episode. Our framework contributes to the strategy-as-practice literature by identifying the importance of spaces in conducting strategic work and providing insight into the way that these spaces are constructed.

Introduction

The recent emphasis on materiality in practice research generally (e.g. Leonardi and Barley, 2010), and strategy-as-practice research specifically, has emphasized that people do strategy with ‘stuff’ (Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013). That is, strategists cannot be separated from the artefacts such as spreadsheets, flipcharts and computer screens (Vaara and Whittington, 2012), bodily performances or spatial arrangements through which they do strategic work (LeBaron and Whittington, 2011). Yet many studies in strategy-as-practice have focused on discursive practices (e.g. Balogun, Jarzabkowski and Vaara, 2011; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011; Samra-Fredericks, 2003), examining talk-based interactions and underplaying the bodily, material and spatial aspects of strategic work. Hence, while burgeoning research points to the critical role these additional resources play (e.g. Hodgkinson and Wright, 2002; Kaplan, 2011; Liu and Maitlis, 2014), we still have only partial understanding of the ways in which they are orchestrated or implicated in accomplishing strategic work. To address this blind spot, Vaara and Whittington (2012) have called for strategy-as-practice research to ‘go beyond discourse to consider how the material, in the form of both bodies and artefacts, is used to accomplish strategy work’ (2012, p. 316). Such calls encourage researchers to adopt a multimodal lens, to examine the interplay of bodily orientations, gestures, gazes, material artefacts and talk (Streeck, Goodwin and LeBaron, 2011), in order to enrich our understanding of how actors perform strategic work.

We respond to this call by exploring the orchestration of bodily, material and discursive resources in accomplishing strategic episodes. Our paper first highlights gaps in understanding about the way these resources come together in performing strategic work. We then develop an inductive analysis building on a video-ethnographic study of strategic episodes for making capital allocation decisions on reinsurance deals, which examines the everyday interactions through which reinsurers enact their firm's strategic portfolio within the particular spatial–material arrangements of a reinsurance trading desk. Our findings show that actors construct three distinct spaces through different orchestrations of bodily, material and discursive resources. We show that these spaces are consequential for the types of strategic work performed and for accomplishing the particular outcomes of the strategic episode. Drawing on these findings, we generate a conceptual framework for understanding strategic work as a spatial accomplishment and describe the specific contributions that our framework makes to the strategy-as-practice field.

Theoretical framework

This study builds on the foundations of strategy-as-practice research (Jarzabkowski, Balogun and Seidl, 2007; Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003; Johnson et al., 2007; Whittington, 2003, 2006) by focusing on strategizing as the ‘actions, interactions and negotiations of multiple actors and the situated practices that they draw upon’ (Jarzabkowski, Balogun and Seidl, 2007, pp. 7–8). While this research agenda exhorts us to focus on actual strategic work – what managers do when they enact strategy – (e.g. Jarzabkowski, 2005; Jarzabkowski and Whittington, 2008; Whittington, 2003, 2006) there are still only partial understandings of what this work comprises. In particular, existing research has focused on the discursive work of doing strategy (Balogun et al., 2014). This has provided valuable insights into the discursive practices through which managers at different levels of the firm participate in (Mantere and Vaara, 2008), make sense of (Balogun and Johnson, 2004; Rouleau, 2005) and enact their strategic roles (Mantere, 2008; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011). Such discursive work is undoubtedly consequential in developing, sharing and implementing strategy, including negotiating through the inevitable ambiguities and contradictions that are integral to strategizing (e.g. Abdallah and Langley, 2014; Dameron and Torset, 2014; Kwon, Clarke and Wodak, 2014; Sillince, Jarzabkowski and Shaw, 2012). Discursive practices are, for example, central to the way that middle managers make sense of and enact organizational restructuring during strategic change (e.g. Balogun and Johnson, 2004; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011). Discourses also inform what is considered strategic (Hardy and Thomas, 2014), fuel resistance (Balogun, Jarzabkowski and Vaara, 2011), shape the objectives included in a firm's strategy (Kaplan, 2011; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011), and enable and constrain the development of strategic orientations (Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008; Vaara, Sorsa and Palli, 2010). In a particularly illuminating study, Samra-Fredericks (2003) illustrated how a strategist shaped a firm's strategic investments through skilfully employing discursive resources during a management meeting to draw attention to two organizational weaknesses. Discursive resources are thus an important part of strategizing.

However, as recent calls to extend our focus to the sociomaterial elements of strategy indicate, a focus on discourse alone provides only partial understandings of how strategic work takes place (e.g. Balogun et al., 2014; Vaara and Whittington, 2012). In this vein, some recent contributions have begun to shed light on how PowerPoint, flipcharts and documents are constructed and mobilized during interactions (e.g. Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011; Whittington et al., 2006). As they become part of strategic activities, these materials acquire meaning, even as they also afford particular types of strategic interactions. For example, Kaplan (2011) illustrates how the use of PowerPoint mediated the discursive practices of strategy making by enabling actors to collect, represent, share and edit ideas. Yet the spatial and bodily activities for accomplishing strategic work have received only limited attention within strategy-as-practice research (e.g. LeBaron and Whittington, 2011; Liu and Maitlis, 2014). Liu and Maitlis (2014), for instance, illustrate the importance of the physical body in their investigation of how emotional displays – using facial, physical and verbal cues – shape the strategizing process. Hodgkinson and Wright (2002) also illustrate the strategic consequentiality of bodily, spatial and material work with their reflective account of a failed strategy intervention that shows how powerful actors use their physical bodies (e.g. sitting remotely, pacing up and down) and material objects (e.g. marker pens and white boards) to control meetings. Despite these contributions, few studies have considered the role of material or bodily performances in strategic work. Thus, a blind spot remains around how bodily and material resources are employed, either singly or in concert, to accomplish strategic work.

In part, this gap may be attributed to the problem of identifying what and whose work is strategic. Strategy-as-practice has long called for research that extends beyond top managers (Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011) or those specifically labelled strategists (Jarzabkowski and Spee, 2009; Whittington et al., 2003). Indeed, Floyd and Lane (2000) emphasize that strategizing occurs at multiple levels of the firm, while Mantere and Vaara (2008) examine how managers participate in strategy at different levels. Yet the ‘strategic’ nature of these actors' work is often not apparent until after the fact. For example, Salvato's (2003) study showed how the combination and recombination of micro-strategies shaped critical firm evolution in two firms, Alessi and Modafil. Similarly, Regnér (2003) shows how exploratory product experimentation by peripheral managers enabled Ericsson's strategic shift into the mobile telephony market. Other studies illustrate the importance of sales managers' micro-actions in translating and enacting firm strategy (e.g. Rouleau, 2005; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011), or orchestra members' political discourses in strategic failure (Maitlis and Lawrence, 2003). And yet, a priori, few would have identified these operational managers, middle managers, sales managers and orchestra members as strategic actors, or their talk, their tinkering and their everyday, often routinized, business actions as strategic work. Yet, it is through the everyday enactment of this work that strategies of firms are brought into being and accomplished. As Chia and Holt (2006, p. 637) note, ‘Strategy is not some transcendent property that a priori unifies independently conceived actions and decisions, but is something immanent – it unfolds through everyday practical coping actions’. The practical coping that Chia and Holt (2009) advocate encourages us to move beyond overtly strategic work as it is displayed by purposive actors and give more serious attention to how actors in situ engage with the spatial and material arrangements to hand (Heidegger, 1962; Schatzki, 2005).

In order to address calls to go beyond studies of the ‘overtly strategic’, such as top managers and strategic plans, we must examine the strategic episodes of managers outside the top team whose everyday actions enact a firm's strategy and are critical to a firm's ‘wealth-generating capability’ and ‘long term survival’ (Hendry, 2000, p. 970), wherever they take place in a firm. In this paper we focus on a particular group of professional actors who have high autonomy for making decisions that enact core aspects of their firms' strategies (Løwendahl and Revang, 1998). Specifically, we examine the everyday practice through which a group of reinsurance managers enact the capital allocation decisions that are necessary to fulfil their firm's strategy portfolio. The strategic consequences of these everyday decisions are critical – failure to fulfil the portfolio with appropriate deals inhibits the firm's wealth generating capability, while over-exposing the portfolio to risk can cause the firm to collapse – and yet such high-stake decisions are also part of these managers' routinized practice. We undertake an inductive ethnographic analysis of strategic episodes of these managers at their trading desks, in order to address the research question: how is strategic work accomplished through the orchestration of material, bodily and discursive resources?

Methods

Research setting

We explore this research question within a finance sector setting where individuals' interactions are consequential to a firm's or even an entire market's success or failure, as illustrated in the previous global financial crises (cf. MacKenzie, 2005, 2011; Preda, 2009). Our research setting is the Lloyd's reinsurance market located at the heart of ‘the City’ of London. Reinsurance, the insurance of insurance companies, is traded on the basis of a reinsurance deal. It provides a large amount of capital to cover an insurer from mass damages to multiple insured dwellings simultaneously, such as that arising from natural catastrophes like earthquakes or flooding. Capital allocation is thus the core business of any reinsurance firm. To manage risk, reinsurance firms develop specific capital allocation portfolios, as part of their annual business planning, that are at the heart of their strategy. These portfolios allocate capital strategically across a diversified portfolio of deals, typically differentiating between territories (e.g. the USA, Japan, Australia). For example, they may have a strategic plan to allocate £50 million of their capital to deals in Japan whereas deals in Europe are allocated £200 million and other territories other amounts. To enact this strategy, reinsurance underwriters (hereafter reinsurers) must make a series of strategic decisions on which deals they regard as the best use of the £200 million of capital for Europe and so forth. They typically appraise several hundred deals throughout the annual cycle, placing capital on around a tenth of those that they deem to fit with the firm's strategic portfolio. These finance professionals, then, have direct responsibility for making a series of everyday, but strategically consequential, capital allocation decisions for their firms, which dictate whether a firm will meet their strategic targets for capital return.

We conceptualized these interactions within which reinsurers allocate capital on deals as important ‘strategic episodes’ because they had a clearly defined initiation, conduct and termination pattern (Hendry and Seidl, 2003; Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008) and the work done within them was strategically important. For instance, we often observed reinsurers' strategic work and hatching plans for allocating capital: ‘we need to watch our exposure in this region’, ‘we need to funnel more business to our sister company’, ‘this client could provide us with a valuable foothold in the region’. The allocation of this capital to specific deals was then negotiated in intense interactions between reinsurers and brokers (see the Appendix). Brokers represent several reinsurance deals on behalf of many clients, seeking to attract capital for these deals from reinsurers. These interactions are strategically consequential in two ways. First, reinsurers aim to select the best deals on which to place their finite pot of capital, in order to provide the highest return for their firm with the least likelihood for payout (Outcome 1). Inability to fulfil the portfolio with sound deals has a direct impact upon their firm's strategic performance as capital may be underutilized, so generating inadequate returns for investors, or overstretched, so exposing the firm to financial collapse. They thus need brokers to present them with a suitable array of deals and to provide them with as much information as possible from which to judge the potential returns on their capital. Yet, reinsurers cannot allocate capital to all of the deals that a broker shows them. Hence, while they will often not be able to achieve a business transaction, a second critical outcome is maintaining good business relationships during these strategic episodes (Outcome 2), in order to ensure that brokers will continue to provide them with attractive business opportunities.

Data collection

This paper is based on a year-long ethnography of reinsurers' practices to allocate capital on selected reinsurance deals. The main source of data is extensive field notes, collected as we observed underwriters' work practices and interactions first-hand in the Lloyd's of London reinsurance market. Notably, we were granted permission to video-record live trading episodes. In total, we collected video-recordings of 23 different reinsurers at their trading desks in Lloyd's, known as the ‘box’, during episodes where they made strategically important capital placement decisions. While recording, we inserted time markers in our observational notes every 5 minutes, so that they corresponded precisely to the video material and could be incorporated into our database. These notes were critical in enabling us to track our emerging findings, develop tentative theorizing and shape future data collection. As our analysis became more focused, we were able to use the time markers to revisit and analyse specific sections of the video-recorded episodes to gain greater insight into specific spatial and bodily arrangements as they occurred across a corpus of data. This provided an unusually rich data set that allowed us to revisit spatial–material elements of interaction during analysis and check the reliability of our emerging interpretations (LeBaron, 2005; Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

In addition to these extensive observations, we conducted formal interviews with each of our video participants, which were recorded and transcribed verbatim. These interviews provided further insights into the strategic rationale underlying reinsurers' decisions about how to allocate capital to specific deals, how they understood their interactions at the box, and what purpose these interactions with brokers served within their everyday strategic work of making decisions on deals. We also interviewed brokers and representatives of the London reinsurance market to gain a broader understanding of the interactions we observed. While these wider interviews do not comprise the data set for this particular paper, they sensitized us to the overarching context of the episodes we explain here.

Data analysis

We drew on both detailed ethnographic field notes and video-recordings of interactions between a reinsurer and a broker to explore how participants accomplished outcomes that were strategically consequential for the reinsurer. For this paper, we undertook a detailed microanalysis of ten video-recorded strategic episodes.Each episode lasted approximately 10–25 minutes, passed through phases of initiation, conduct and termination (Hendry and Seidl, 2003) and was associated with semiotic patterns that affected the enactment of specific strategic decisions associated with fulfilling the firm's strategy portfolio. These strategic episodes were an ideal unit of analysis because they were oriented towards accomplishing two specific strategic outcomes: (1) progressing capital allocation decisions and (2) preserving key sources of future business opportunity. Analysing these episodes enabled us to develop a deeper understanding of how bodies, materials and discourse were used together to accomplish key strategic outcomes.

Early analysis began in the field when our attention was drawn to the physical arrangement of the trading space, known as the box, and the ways in which actors used their bodies and different materials when engaging in strategic work (see the Appendix). In particular, we started to take detailed notes about how actors oriented their bodies and used different materials (e.g. screens, information packs, notepads etc.) when doing work together. These observational notes were then organized in NVivo to enable more formal interrogation. Using open coding (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Strauss and Corbin, 1990), we generated initial conceptual categories about bodily positions (e.g. ‘sitting orthogonally’), bodily movements (e.g. ‘leaning in’), verbal tendencies (e.g. ‘silences’) and material use (e.g. ‘placing notepad on desk’, ‘turning computer screen’).

These inductive insights sensitized us to the multiple semiotic resources in the observed interactions. We became interested in understanding how actors orchestrated these various modalities, including speech, bodily orientation and materials, to communicate, build meaning and mutually accomplish work. Sensitized to these modalities, we undertook a systematic analysis of the video-recordings, transcribing talk, noting silences, studying bodily orientation, gesture and use of materials. Based on the specific orchestration of semiotic resources, we noticed that actors were forming different kinds of material–body connections that created different kinds of spaces, which we labelled ‘dialogic space’, ‘mutual space’ and ‘restricted space’, and which are illustrated in the findings. We then studied and coded the activities being performed in each space, and noticed that different types of activity were performed in different types of space (see Table 2). We analysed these space–activity relationships across all the episodes and kept seeing the same patterns of activities, which gave us confidence that we had reached theoretical saturation (Glaser and Strauss, 1967, p. 61). As we clustered these activities, we identified broader thematic categories (Gioia, Corley and Hamilton, 2013) about the strategic work being done through such activities, which we labelled ‘negotiating work’, ‘private work’ and ‘collaborative work’. These types of work are illustrated in our findings. Having identified the distinct spaces within which particular strategic work was performed, we then examined the transitions between these spaces and work, recognizing that these transitions were important in enabling different types of activities. Based on the shifts in the use of bodily, material and discursive resources, we identified various transition points, such as ‘self-instigated’, ‘invitational’, ‘disruptive acts’ and ‘closing off space’, while also recognizing that these transitions were fluid. Having developed three main categories of space and associated types of strategic work (summarized in Table 2) we then examined the relationship between these categories and their consequentiality for the outcomes accomplished in the strategic episode, which comprises the basis for our findings below and our conceptual framework in the discussion.

Findings

Our findings are presented in three sections. First, we introduce two representative examples of strategic episodes to illustrate how speech, bodily and material resources were simultaneously employed during reinsurer–broker interactions. Second, based on our analysis of all ten episodes, we show how actors used constellations of semiotic resources to construct three distinct spaces. Finally, we explain how the specific activities in each of these spaces constituted three distinct kinds of strategic work that enabled the accomplishment of strategic outcomes.

Strategic episodes and patterns of semiotic performance

In strategic episodes we watched reinsurers work with brokers to generate business opportunities, arrive at decisions about deals and maintain strategic business relationships. Two examples of these strategic episodes are presented in Table 1. In episode 1, Nigel (reinsurer) and James (broker) constructed a novel solution which enabled Nigel's firm to place capital and generate a strategic opportunity for their sister company in Europe. In episode 2, Mike (reinsurer) considered some US business presented by Ben (broker) but decided not to trade due to strategic concerns about profitability and portfolio management. Such strategically consequential outcomes generated on the trading floor were not predetermined but were ‘accomplished’ through the mutual work of the actors involved.

| Episode 1 | Constructing a solution |

| 19:28 minutes | Nigel (the reinsurer) eventually turns his head towards James (the broker), which opens the interaction, and they engage in some small talk before turning to the business at hand. James is returning with the pricing of a deal that was slightly lower than Nigel had expected. At the beginning of the episode, James and Nigel discuss the details of the deal, particularly some new insured dwellings that it contains. This development is a concern for Nigel. He is worried that this will give his firm exposure to additional risk he had not planned for when evaluating the deal initially. Thirteen minutes into the exchange, however, Nigel puts forward a potential solution which would enable his firm (ReinCo) to place capital on the deal, while also creating a new commercial opportunity for their sister company in Europe (EuroRe). This opportunity emerges as Nigel queries: ‘Do Europe write this as well?’ After some discussion about EuroRe's involvement, Nigel proposes that they could offer the same amount of capital, but that EuroRe could be introduced to take a split so that he places around half of the desired amount of capital while EuroRe offers the remaining capital to match the overall capital allocation that James would like. He explains his thinking to James: ‘From a group perspective we can handle around 50%. But it might be an opportunity for Europe. … I think they have tried to write this in the past but there hasn't been an opportunity for them. But if we take our line down it might give them an opportunity.’ Initially, James is not enthusiastic about Nigel reducing his line, particularly as he was hoping to wrap up the deal. However, they discuss how this might work and James eventually concedes there could be an opportunity for EuroRe to place an equivalent amount of capital on the deal. They agree Nigel will pursue this internally and that they will meet later in the week. |

| Episode 2 | Deciding not to trade |

| 10:03 minutes | The interaction begins when Ben (the broker) comes to the box with a major US wind programme he is trying to place. Mike (the reinsurer) states early in the interaction, ‘I have already placed a lot of capital on US wind … our book is virtually full’. However, he also leaves open the possibility of writing additional business if the right opportunity comes along: ‘I mean if the prices really did kick-on then I suppose there is an argument for opening up the book’. The deal itself covers four coastal zones in the USA and Ben is looking at a 15–20 million limit across the regions, but Mike tells Ben, ‘That's far too low for me’, meaning that the risk is too great for their portfolio. He explains: ‘I mean we are in pure defensive mode in terms of what we are writing now. You know the only deals we will write over the next 6 weeks will be middle and top end stuff – away from losses and paying a good price. We're not doing anything below 25 at this stage and most of our business is 40 million upwards.’ Even so, Ben encourages Mike to speculate on what kind of price he would be looking at for a 20 million limit. Mike gives him a rough price, but immediately qualifies this by saying, ‘But it's far too low for me … we have taken the book up and away’. There is some discussion about the pricing and Ben tries to persuade Mike to reconsider, which he thinks about, including doing some brief calculations, before restating his position, ‘We are full’, at which Ben thanks Mike ‘for your consideration’ and leaves. At a debriefing after this interaction, Mike explains his decision to the researcher: ‘I've filled my portfolio on the USA. We have a plan for capital allocation and, of course, I can go over it if there is a good reason – pricing is high – or it gets me something else I want. So I might have, you know … but this deal, there's nothing wrong with it, but it just wouldn't pay enough extra when we've met our targets for the USA already.’ |

These episodes can be partially understood by focusing on what was said during the interactions. However, closer inspection reveals that multiple semiotic resources were being employed throughout and were ‘crucial to how participants … built action together’ (Goodwin, 2003, p. 20).

Speech resources

These kinds of short silences were common in all the episodes. In episode 2, for instance, they happened when Mike stated ‘No, we are full’ in response to Ben's petitions. This categorical statement triggered a prolonged silence in which Mike and Ben just looked at each other, seemingly each waiting for the other to fill the discursive void. Later, Ben used silences as if trying to invite Mike to elaborate or change his position.Nigel just looks at James and does not speak. After a few seconds he says, ‘It's too low’. There is then another 6-second silence before James starts to argue that there are some incorrect assumptions in the original exposure figures.

At the end of the interaction Ben picks up his folders as if to leave and gives Mike a long final look without speaking. With no response from Mike, Ben eventually says, ‘Okay then … [3-second silence] … thank you’ and leaves.

Material resources

The use of material resources was also central to the work being accomplished. The compact nature of the space, and the density of materials located within it, provided both actors with an array of opportunities to interact with materials, such as highlighting pens, notepads, reports, information packs, information sheets, the desk, calculator, mouse, keyboard, the computer screens. The use of materials was partly determined by differential ownership and layout. For example, reinsurers ‘owned’ the desk area, the keyboard and the computer screens, while brokers controlled the information packs, notepads and reports that they carried into the space, and the orthogonal seating arrangement meant that reinsurers were positioned facing their computer screens, while brokers sat to the side facing the reinsurer.

However, these materials were used in some very proactive ways. On some occasions actors worked with material objects independently. In episode 1, for example, Nigel concentrated on his computer screen for 45 seconds, studying figures and switching between spreadsheets, while James sat quietly watching him (see Image 2). A similar pattern was observed in episode 2, when Ben (the broker) focused on his notepad (see Image 6).

Ben takes a US coastal map out of his briefcase and places it on the desk in front of Mike. He then borrows a highlighter pen and starts drawing circles on the map to illustrate the risk. Mike is immediately drawn to the document and it becomes a focal point for the ensuing discussion. Both Ben and Mike touch, point and write on the map. They number the zones, point to them, mutually assign values and discuss the differences between Florida and North Carolina.

Finally, peripheral objects (briefcase, telephones, pens, photographs) were sometimes enrolled in performing the episodes. An example of this occurred when Nigel focused on his computer, essentially ignoring James. In the field note below, we describe how a simple act of taking, opening and commenting on a peripheral object, such as a sweet, reengaged Nigel and allowed James to continue arguing the merits of the deal.

Finally, peripheral objects (briefcase, telephones, pens, photographs) were sometimes enrolled in performing the episodes. An example of this occurred when Nigel focused on his computer, essentially ignoring James. In the field note below, we describe how a simple act of taking, opening and commenting on a peripheral object, such as a sweet, reengaged Nigel and allowed James to continue arguing the merits of the deal.

After a long period James starts to fidget, exhale breath and tap the table, seemingly to distract Nigel and reengage his attention. Eventually, James stretches out his right arm and takes a sweet out of a jar on Nigel's desk, keeping his eyes fixed on Nigel (see Image 2). As he unwraps the crackly plastic wrapping of the sweet he makes an incredible amount of noise. He places the sweet in his mouth, utters a sound of contentment (Mmmm) and comments on the taste of the sweet. Nigel suddenly looks up, smiles and says: ‘They're very good aren't they!’

Bodily resources

James sits down and places his information sheet on the desk in front of Nigel, directing his attention to the revised exposure figures he wants him to read (see Image 3). They both ‘lean in’ and look at the sheet together, discussing the information it contains.

A similar pattern occurred later in this episode when Nigel ‘turns his computer screen so that James can see it’ (field note), triggering a transition into a new bodily formation in which Nigel and James studied the exposure figures together and Nigel used the material to justify his EuroRe proposition. When actors focused on different objects in the space (see Image 2), by contrast, one actor interacted with the material(s) – e.g. turning pages, reading, typing, moving mouse, pushing buttons, writing etc. – while the other sat relatively still, often keeping his gaze fixed on his counterpart, although, as we noted above, brokers would sometimes fidget, exhale or tap tables to try to distract reinsurers to regain their attention. Actors did not, of course, always focus on materials. They sometimes focused on each other (see Images 1 and 4), using subtle facial expressions (e.g. smiling, frowning, rolling eyes, exhaling etc.) and bodily movements (e.g. nodding, looking left and right, leaning in).

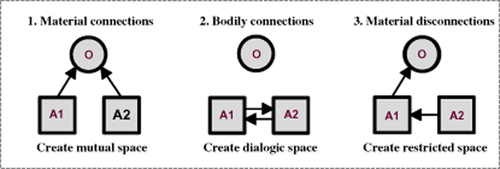

The creation of spaces for work

The active use of speech resources (including silence), material resources and bodily resources enabled actors to co-create and work within distinct kinds of spaces associated with the connections illustrated in Figure 1. Each type of connection manifested a different kind of space, which we have categorized as ‘mutual space’, ‘dialogic space’ and ‘restricted space’. Within each of these spaces we found particular types of activities being performed, which are summarized in Table 2. We now look at each in turn.

The creation of spaces for work: A1, actor 1; A2, actor 2; O, material object. Arrows indicate the orientation of each actor

| The construction of spaces within spaces | Types of activities | Representative data | Strategic work accomplished |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Mutual space Constructed when actors use constellations of semiotic resources to create material connections wherein both actors focus on the same material object – e.g. a figure on a screen, a calculation jotted down on a notepad, a key piece of information in the information pack |

1a. Directing each other's attention |

|

Collaborative work Created the opportunity for a reinsurer and a broker to accomplish tasks together. The practitioners worked concertedly with common materials to align meanings and establish areas of common ground. They directed each other's attention to salient, critical and ambiguous information, enabling them to ‘zoom in’ on what was important. They sketched illustrations to co-define the parameters of risks and explored the possibility of allocating capital. By working collaboratively reinsurers made brokers ‘aware’ of the commercial underpinnings of their positions, providing the ground for negotiating work (below) and making it easier for brokers to accept decisions because they could see ‘how’ and ‘why’ a reinsurer got to a position |

| 1b. Sketching illustrations pertaining to the deal |

|

||

| 1c. Mutual calculating |

|

||

|

2. Dialogic space Constructed when actors use constellations of semiotic resources to create moments of face orientation wherein actors fix their gaze on each other and adopt a mirrored body position |

2a. Discussing proposals and terms |

|

Negotiating work Created the opportunity for a reinsurer and a broker to engage in face-to-face dialogue. Negotiating work enabled the practitioners to reconcile differences, progress the capital allocation decision and establish the grounds for furthering acceptance or decline of the deal. Using this space the practitioners discussed terms and exposures, they put forward capital placement offers or alternative capital solutions, they explained the rationales underpinning their decisions and they tried to work through sticking points. While each practitioner searched for a more attractive position, they were respectful and sensitive to the other's position. The subtle use of silences, facial expressions and gestures allowed the actors to signal areas of (dis)satisfaction, and invite each other to elaborate upon, and alter, positions |

| 2b. Signalling areas of (dis)agreement |

|

||

| 2c. Inviting each other to elaborate upon, and alter, proposals |

|

||

|

3. Restricted space Constructed when actors use constellations of semiotic resources to create moments of disconnection wherein practitioners focus on ‘different’ things |

3a. Absorbing information and making notes |

|

Private work Private work enabled practitioners to temporarily disengage and work in restricted space to which they had exclusive access and were free from interruption. Private work allowed reinsurers to consider and make progress on a decision of whether or not to allocate capital to a particular deal, by allowing them to absorb complex information, wrestle with complex deals, undertake detailed analysis, consider commercial options, generate viable commercial positions and think through possible solutions |

| 3b. Doing private calculations |

|

||

| 3c. Focused thinking |

|

1. Mutual space

Adam (broker) and Harry (reinsurer) are discussing a European earthquake and flood deal. Harry has written this deal for several years, but he tells Adam he may have to reduce his capital allocation this year given its poor loss record and increasing exposure. As he is explaining to Adam, Harry turns his computer screen so that Adam can see, pointing at the losses column in the spreadsheet. Adam looks and says, ‘I know, but the pricing is better than last year’. Adam then lays a sheet labelled ‘additional analysis’ on the desk in front of Harry and points to some remodelled data, which he explains as providing more favourable margins. They study the sheet together and discuss the veracity of the data. Harry jots some figures while they talk, does some quick calculations on his calculator, and writes the calculated figures on the margin of Adam's sheet. He then circles and points to the figures with his pen as he talks.

In this, and our other episodes, we noticed particular types of activities being done in mutual space which we labelled ‘Directing each other's attention’, ‘Sketching illustrations pertaining to the deal’ and ‘Mutual calculating’ (see Table 2, section 1). As episode 3 shows, in mutual space actors often turned their screens or placed documents to direct each other's attention to particular files, figures, maps, diagrams, passages etc. Such directing activity raised the actors' sensitivity to particular materials, encouraging them to zoom in on, and jointly engage with, information embedded in the object. This activity often prompted questioning (‘What is the difference?’), surfaced knowledge gaps (‘I don't know’) and motivated future action (‘I will strip that out for you’).

Mutual calculating was another activity performed in mutual space. In Table 2 (1c), for example, the reinsurer and broker worked closely to perform calculations and make sense of the figures. Working together, both actors provided input, vocalized assumptions, exerted influence and worked towards a common understanding of what the figures represented. In such situations, actors often sketched illustrations pertaining to the deal, such as drawing blocks that represented the specific layers of risk. For example, in episode 2, Ben drew circles on the US coastal map to illustrate the risk to Mike.

2. Dialogic space

This moment of interaction was typical of the activities performed in dialogic space, which always involved ‘Discussing proposals and terms’, ‘Signalling areas of (dis)agreement’ and ‘Inviting each other to elaborate upon, and alter, proposals’ (see Table 2, section 2). Dialogic space invited a discussion between the parties about issues such as terms, capital allocation and commercial proposals within which each could advance their interests and negotiate outcomes. In this space, actors utilized an array of expressive physical acts, including facial expressions (e.g. grimacing, smiling, laughing, frowning), head movements (e.g. nodding, moving head side-to-side, looking up to sky) and expressive hand gestures (e.g. using hands to fabricate images) to signal areas of agreement and disagreement and build common understanding.Adam and Harry lean out and are now looking directly at each other. Harry says, ‘OK, I'll do 8.5% on all the layers’. Adam says ‘right’ and stares back at Harry without speaking, but gently nodding his head. After 7 seconds of silence, Harry starts to justify his offer by referring to the overall firm portfolio: ‘Our European book is really tight now’. Adam says, ‘Look, take it to up to 9% and the client will be happy. You'd be doing me a favour.’

An important semiotic resource frequently employed in this space was conversational silence. Conversational silences were used by actors to invite each other to elaborate upon, and alter, their positions. In episode 3, for instance, we saw how Adam's silence conveyed dissatisfaction with Harry's 8.5% offer, which encouraged Harry to elaborate. The same happened in episode 1 when James's short silence, following Nigel's EuroRe proposal, signalled to Nigel that the proposal was suboptimal, prompting Nigel to further explanation. Similarly in episode 2, Ben's silences appeared to invite Mike to elaborate upon, and potentially alter, his position.

3. Restricted space

Harry turns his body away from Adam and focuses on his computer screen, while Adam sits quietly. Harry taps away at his keyboard, entering figures, and flicking back and forth between two spreadsheets he has open. As he does this he jots down two figures on a small yellow notepad. He drops the pencil and lifts both hands into a prayer-like position, resting them against his lips. He stares intently at the screen (27 seconds) while tapping his two index fingers together. He is deep in thought. At one point Adam asks ‘what do you think?’ but Harry doesn't answer him; he just continues looking at his figures.

This fragment is typical of the activities performed in restricted space. When one actor was in restricted space, the other person's ability to take control or observe the ‘doings’ of the other was significantly restricted because material positioning, bodily orientations and norms of conduct prevented him from doing so without invitation. For instance, Adam could no longer see Harry's screen because Harry had returned it to its original position. Even though Adam used verbal talk to try to interrupt Harry (‘what do you think’) he was restricted from entering Harry's space. In our study, it was primarily reinsurers who generated restricted space because the spatial–material configurations privileged their ownership of the space (e.g. they faced the computer screen and it was their desk). Norms of conduct also privileged the reinsurer withdrawing into restricted space to work on the information brought by the broker, whereas brokers were there to interact and hence had less reason, by custom and work performed, to construct restricted space. Even so, we did sometimes see brokers construct restricted space, for example to read a document, do a quick calculation or consider a piece of information to proffer.

When in restricted space, actors performed private calculations; doing analytical work, calculating on spreadsheets and comparing figures, as well as absorbing information and making notes, including reading documents and writing on private notepads. Focused thinking went hand-in-hand with these activities as actors studied figures, evaluated information, wrestled with alternatives and formulated commercial proposals. While we cannot know for sure what actors were thinking while performing this activity, the visual cues strongly suggest this is what was happening. In episode 1, for example, Nigel took regular ‘time-outs’ to consider information presented, contrast it with his commercial analysis and think through options that he then articulated. Moreover, as shown in the post-interaction reflection following episode 2, our post hoc conversations with reinsurers often confirmed our impressions and interpretations.

Moving between spaces to perform different activities

In sum, our fine-grained analysis revealed that actors created three distinct spaces that enabled them to perform particular activities associated with allocating capital on reinsurance deals (see Table 2). Our categories point to those activities that were germane to each space. For example, mutual calculating could only happen in mutual space, just as we only saw private analytical work in restricted space and actors inviting further elaboration in dialogic space. In other words, these critical activities could only happen because the actors constructed the appropriate spaces.

As our representative examples show, the activities accomplished in these episodes shifted fluidly and easily between the three spaces. These transitions were shaped by the momentary circumstances created in the episode. Sometimes transitions were self-instigated and instantaneous, such as when a reinsurer broke eye contact and switched attention to a document, moving the interaction into restricted space, or turned and focused on the other person, moving the interaction into dialogic space. Other times transitions were invitational, wherein one of the actors would invite the other to enter into mutual space, such as when a reinsurer turned his or her screen towards a broker and invited him or her to look at figures or when a broker placed an information sheet on the desk and invited the reinsurer to look at it. On a few rare occasions, transitions were triggered by disruptive acts, such as when an actor made a comment, tapped a pen on a desk, or performed some other disruptive act that led to a change in the space. Recall how in episode 1 James (broker) used his body (e.g. fidgeting, tapping) and materials (the sweet) to disturb Nigel and move the interaction from restricted space into dialogic space. Finally, transitions were sometimes brought about when an actor closed off space, such as when reinsurers returned their screens back to their original position, out of sight of the broker, or when brokers took back documents that had been the focus of attention.

Spaces and strategic work: accomplishing strategic outcomes

Our findings so far show that spaces and the activities performed within them constitute one another and, as we will now show, are consequential for the accomplishment of strategic outcomes. Specifically, the cluster of activities performed within each space constituted a type of strategic work that contributed to the accomplishment of strategic outcomes during an episode. We labelled these three types of strategic work ‘collaborative work’, ‘private work’ and ‘negotiating work’. These three types of strategic work enabled the accomplishment of at least two key strategic outcomes during an episode. First, they enabled reinsurers to progress towards a decision on whether or not to allocate capital to a deal (Outcome 1). Second, they enabled reinsurers to preserve good business relationships, thereby preserving their key sources of future business (Outcome 2), of vital importance given that reinsurers cannot allocate capital on all deals and decisions reached are often suboptimal for brokers. We now discuss the links between each type of strategic work and strategic outcomes, and then discuss their interconnected nature.

Collaborative work

Collaborative work was jointly accomplished and performed in mutual space using the three activities explained above (see Table 2, section 1). In episode 1, for example, we saw how Nigel turned his computer screen to show James ReinCo's analysis of the risk exposures. By studying the exposure modelling ‘together’, Nigel was better able to explain to James the commercial reasons behind ReinCo's decision to reduce their capital, thus helping to preserve the relationship (Outcome 2). This collaborative work also helped to open up the opportunity for EuroRe, propelling the episode closer towards a capital placement decision (Outcome 1). While this was not an ideal solution for James, he ‘understood’ Nigel's position and the two were able to reach common ground on the proposed capital allocation (Outcome 1). Collaborative work was also central throughout episode 2. By sketching the deal using the US coastal map, for instance, Ben and Mike were able to co-define the parameters of the deal (e.g. numbering zones, comparing zones, assigning values to the zones) and explore the possibility of allocating capital. Working with this material resource together (e.g. pointing index finger, circling figures), Mike was able to comprehend what the deal entailed and eventually reach a decision not to place capital (Outcome 1). Although this was not an ideal outcome for Ben, the collaborative work made it easier for Ben to accept the decision because he could see why Mike held his position. In other words, collaborative work played an important part in fostering mutual acceptance of each other's position, which helped to maintain the relationship and leave open the possibility for future engagement (Outcome 2). In episode 3, collaborative work was evident when Harry turned his computer screen to explain to Adam why he might reduce his capital allocation (Outcome 2) and when Harry and Adam both studied the sheet labelled ‘additional analysis’ together. This collaborative work was important in leading Harry to put the 8.5% offer on the table (Outcome 1). Table 2 (section 1) provides further illustrations of how collaborative work – e.g. directing attention, drawing illustrations pertaining to the deal and mutual calculating – enabled similar accomplishments in other episodes.

Negotiating work

Negotiating work was performed in dialogic space and involved the three activities explained above (see Table 2, section 2). Negotiating work played a crucial role, alongside collaborative work, in moving the episodes towards both strategic outcomes, particularly the primary strategic outcome of a decision about allocating capital. In episode 1, for example, James's short silence when presented with Nigel's EuroRe proposal sent a clear signal to Nigel that the proposition was suboptimal for James, prompting Nigel to further explain his proposition and the reasons behind it (Outcome 1). At the same time, Nigel's verbal talk and facial expressions conveyed that a genuine effort was being made to accommodate James's requirements (Outcome 2), albeit within commercial boundaries. In episode 2 negotiating work was pivotal as Ben tried to persuade Mike to place capital (e.g. encouraging him to speculate, using conversational silences) and Mike explored the offer before conveying his ‘no’ decision (Outcome 1). This negotiating work was conducted with sensitivity as Mike looked Ben in the eye and explained the reasons for the decision, helping to soften the impact and preserve the relationship (Outcome 2). Indeed, it was often during negotiating work that the actors shared anecdotes, jokes, spoke tongue-in-cheek or used familiar expressions, which all helped to personalize the episodes, relieve tension and preserve relationships (Outcome 2). Table 2 (section 2) provides further examples of how negotiating work enabled similar accomplishments in other episodes.

Private work

Private work was performed in restricted space and encompassed the activities explained above (Table 2, section 3). Private work enabled individuals to simultaneously absorb complex information and to consider commercial options. It most obviously played an important role in enabling reinsurers to formulate and reach commercial decisions they considered viable (Outcome 1). In episode 1, for example, Nigel retreated into private work when he wrestled with the exposures and considered the implications for his firm of allocating capital to the deal. In this case, private work did not lead to an increased offer. Nigel had concluded that this was not a good strategic move. While he was looking to reduce his capital, the private work he undertook was instrumental in leading him to generate the solution of bringing in EuroRe (Outcome 1). In episode 3, we also saw Harry retreat into restricted space and perform private work on his computer, where he undertook quite detailed analysis and spent time staring intently at his screen and thinking (27 seconds), as he considered Adam's request to ‘take it to up to 9%’ (Outcome 1). By doing this private work in response to Adam's request, he was also indirectly maintaining the relationship by showing Adam that he was giving his request for a ‘favour’ serious consideration (Outcome 2). In another example (see Table 2, sections 3b and 3c), a reinsurer worked privately as he tapped his keyboard, scribbled notes, played with his calculator and stared into space, seemingly deep in concentration. This private work influenced the outcome of the episode as the reinsurer increased his capital allocation offer from 5% to 7.5%. By doing private work, the reinsurer was able to satisfy the broker who was looking for him to increase his offer (Outcomes 1 and 2) in a way that the reinsurer felt was commercially right for his business (Outcome 1).

Fluid transitions amongst spaces and strategic work

While we have considered collaborative work, private work and negotiating work separately, the fluid transitions between these three forms of work enabled the strategic outcomes to be accomplished. Actors shifted back and forth between performing collaborative work, private work and negotiating work according to the unfolding requirements of the episode. In episode 1, for example, James and Nigel perform negotiating work in dialogic space before shifting to mutual space and performing collaborative work over the specific figures in order to see if the proposition could be made more acceptable to James (Outcomes 1 and 2). In episode 2, Ben performed negotiating work (e.g. ‘conversational silences’), which encouraged Mike to elaborate and alter his position (Outcome 1). Mike then invited Ben to enter into collaborative work in order to explain his rationale for not allocating the capital, thereby establishing a common basis of understanding that helped preserve the relationship with Ben (Outcome 2). As these examples illustrate, the three kinds of work were necessarily interconnected, so that strategic episodes were performed through a complex choreography of strategic work, which was enabled and constrained by the spaces created during the interactions. These three types of strategic work operated in a complementary fashion, enabling actors to accomplish strategic outcomes such as to allocate capital to a deal, in accordance with their firm's strategic portfolio, whilst also maintaining critical relationships with brokers who were vital sources of future business opportunity.

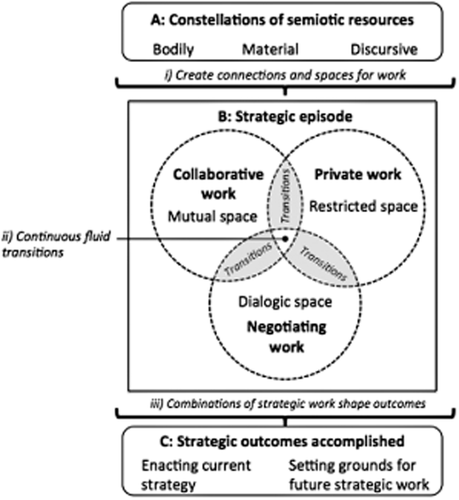

Discussion

In this paper we set out to examine the question: how is strategic work accomplished through the orchestration of material, bodily and discursive resources? We located our study within the context of strategic episodes, those activities that are both part of everyday work and yet strategically consequential for organizations (Floyd and Lane, 2000; Hendry and Seidl, 2003; Jarzabkowski, 2008; Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008). We now draw our findings together into a conceptual framework, illustrated in Figure 2, that revolves around three analytical layers: the creation of spaces; the enactment of strategic work; and the accomplishment of strategically consequential outcomes (hereafter, strategic outcomes). Each of these layers is recursively entwined with the other and each layer is manifested in a particular orchestration of semiotic resources.

Semiotic resources, space and strategic work

As shown in our first-order findings and illustrated in our framework (Figure 2(A)) actors use constellations of semiotic resources – e.g. bodily, speech, material – during interactions, and combine these according to their practical coping with the situation at hand (Chia and Holt, 2009). While there is no predetermined order to employing semiotic resources, their combination creates different connections and spaces for work (Figure 2(i)). We therefore conceptualize these semiotic constellations as important building blocks that shape the conduct of a strategic episode. Specifically, we linked the different semiotic constellations to the construction of different ‘spaces-within-a-space’ during the conduct of an episode. We found that actors construct three types of space – mutual space, restricted space and dialogic space. A strategic episode is accomplished through continuous and fluid transition between these three spaces (Figure 2(ii)), each of which is characterized by distinct activities (see Table 2). As shown in the findings, the co-construction of these spaces is consequential for the types of activities performed within a strategic episode.

The specific clusters of activities in different spaces constitute different types of strategic work: private work performed in restricted space, collaborative work in mutual space and negotiating work in dialogic space (see Figure 2(B)). These three types of strategic work underpin the interactions taking place, shaping the conduct of the episode and its accomplishments. For example, our study showed how fluid transitions (Figure 2(ii)) between the different types of strategic work shaped reinsurers' consideration of capital allocation decisions and their negotiations with critical business partners about these decisions. There is no prescribed pattern in these types of strategic work. Rather, each episode was performed through fluid transitions back and forth between collaborative work, private work and negotiating work according to the unfolding nature of the interaction. Importantly, our study demonstrates that the strategic work performed in each space, and the transitions across spaces, contributed to accomplishing two strategic outcomes (Figure 2(iii)). First, they underpinned enactment of the reinsurer's current strategy within the specific moments of interaction, as each capital allocation decision on a deal is directly tied to enacting the strategic portfolio of the firm. Second, they helped to construct grounds for future strategic work by maintaining critical relationships with brokers, with whom these reinsurers must work daily on pursuing capital allocation opportunities for their firms. While the specific content may vary in different strategy contexts, we suggest that enacting the current strategy whilst also constructing grounds for future strategic work are likely to be relevant outcomes for any strategic episode (see Figure 2(C)). We now turn to the contributions arising from our framework.

Contributions

Our conceptual framework, showing the association between semiotic resources, spaces, strategic work and strategic outcomes, makes several important contributions to the research on strategy-as-practice. The main contribution is our demonstration of how strategic work is accomplished in the orchestration of speech, bodily and material resources (see Figure 2). We show that the construction of spaces is integral to the strategic work performed, and that fluid shifts between these types of work and their associated spaces are critical for accomplishing strategic outcomes. Our study thus elaborates on our understanding of what constitutes strategic work, showing that it constitutes a multimodal accomplishment. Thus far, studies in the strategy-as-practice field have investigated these semiotic resources largely in isolation. While there have been calls to examine a wider range of strategy practices, particularly bringing in multimodal elements such as emotions, bodily positions and material artefacts (e.g. Chia and Holt, 2006; Jarzabkowski and Spee, 2009; Jarzabkowski, Balogun and Seidl, 2007; Vaara and Whittington, 2012), empirical research has largely privileged talk in its various forms over the multifarious affordances of other semiotic resources (LeBaron and Whittington, 2011). Even those studies that have teased apart some of these other semiotic resources (e.g. Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013; Kaplan, 2011; Liu and Maitlis, 2014) have tended to focus upon a subset, such as material or bodily resources. Our findings and framework highlight the multimodality of strategic work, and show how such resources cannot be considered in isolation but rather as constellations of semiotic resources within which particular spaces and activities are mutually constituted.

Our framework also advances research on strategic episodes (Hendry and Seidl, 2003; Hoon, 2007; Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008). While strategy-as-practice research has emphasized the importance of analysing strategic episodes within the overall flow of strategy making (Hendry and Seidl, 2003), we lack an understanding on the role of multiple semiotic resources in enabling and/or constraining the conduct of episodes. First, our study demonstrates the way strategic episodes are constructed in the orchestration of multiple semiotic resources that create spaces for distinct types of strategic work to be performed. Second, it demonstrates the fluid transitions between episodes as the orchestration of semiotic resources shifts, extending current findings that have examined more on the structuring characteristics of strategy meetings (e.g. Haug, 2013; Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008). These prior studies have treated space as a mere background, e.g. referencing the withdrawal to a particular meeting room or off-site location (e.g. Jarzabkowski and Seidl, 2008; Johnson et al., 2010). By contrast, our study makes space an active concept within the analysis of strategic episodes, showing how it is constructed and continuously shifts in accomplishing the episode. Drawing on these insights, future research may explore distinct features of strategic episodes such as the initiation, alternative or competing patterns of conduct and termination and the way these are accomplished within the construction of distinct spaces.

Our research also contributes to the strategy-as-practice agenda to study the actual ‘work that comprises strategy: the flow of activities such as meeting, talking, calculating, form filling, and presenting in which strategy is constituted’ (Jarzabkowski and Whittington, 2008, p. 282; Whittington, 2003) by demonstrating how the construction of spaces and work are entwined. While there have been many calls to study the work of strategy making (e.g. Chia and Holt, 2006; Jarzabkowski, Balogun and Seidl, 2007; Vaara and Whittington, 2012), there are only a few explicit examples of what this work is or how it is performed (e.g. Regnér, 2003; Rouleau, 2005; Samra-Fredericks, 2003), particularly outside boardrooms, and in the work of actors other than top managers (e.g. Regnér, 2003; Rouleau and Balogun, 2011). Our study identified three types of strategic work – private work, collaborative work and negotiating work – and showed how distinct spaces, each created through the constellation of semiotic resources, enable and constrain this work. While transitions between spaces are undetermined and occur instantaneously, each type of strategic work is necessary and performed within a specific space. Yet there is no dominant order or sequence that suggests ‘one best way to strategize’. Rather, strategy ‘unfolds through everyday practical coping actions’ (Chia and Holt, 2006, p. 637); and we show that this practical coping comprises particular configurations of bodily, linguistic and material resources within which actors construct the spaces to perform strategic work. The power of our framework lies in this identification of multiple spaces, the configurations of semiotic resources that underpin them and the fluid transitions between them in performing different and interwoven types of strategic work.

Furthermore, we show that these forms of strategic work are linked to the strategically consequential outcomes of any particular strategic episode. While the consequentiality of micro-strategizing actions has typically been identified in retrospect (e.g. Regnér, 2003; Salvato, 2003), our study provides a more fine-grained understanding of how the outcomes of strategic work are performed in the everyday interactions of strategic episodes, so providing grounds for future research into strategic outcomes (e.g. Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Johnson, Melin and Whittington, 2003).

Our study also advances understanding of semiotic resources and the way they shape strategic work in three ways. First, while many studies have pointed to the critical role of discourse in constructing strategic work (see Mantere, 2013; and Balogun et al., 2014, for reviews) silence as a discursive practice has largely been neglected. Yet, linguistic research has shown that conversational silences have ‘perlocutionary’ effects, such as communicating dissatisfaction or indifference, or persuading or convincing an addressee (Jensen, 1973, Kurzon, 2007). Our study demonstrates that silences comprise important strategic resources that, in combination with other semiotic resources, can signal that actors are withdrawing into restricted space, thus shifting the focus of strategic work, or can invite responses such as further clarification or justification during negotiating work. By demonstrating the importance of silence as a discursive practice that shapes the dynamic flow of strategic work, in interplay with other semiotic resources, we provide grounds for future research to extend analysis of strategy talk to include silences. Scholars may, for example, employ more ethno-methodological or conversation analytical approaches to further unpack how these silences function in different strategy contexts.

Second, our study extends insights on the implication of material resources in strategic work. While there are increasing calls to study the materiality of strategic interactions (e.g. LeBaron and Whittington, 2011; Vaara and Whittington, 2012), strategy-as-practice research to date has focused largely on textual artefacts such as PowerPoint presentations (e.g. Kaplan, 2011) or strategic plans (e.g. Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011). Our study demonstrates the mutability of multiple artefacts in the construction of spaces. For example, a computer screen might be turned towards the other party to construct mutual space in discussing the pricing of a deal (collaborative work), or it may be used as a focal point by a single actor to construct restricted space, so enabling the private work of calculation to take place. The same screen thus contributes to the construction of quite different spaces that afford varying types of strategic work, according to the way it is employed within different configurations of semiotic resources. Our study thus emphasizes the importance of the material turn in strategizing research (Balogun et al., 2014; Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013; LeBaron and Whittington, 2011) and suggests a rich set of possibilities for investigating multiple artefacts, not only those that are overtly ‘strategy tools’, for their role in enacting spaces and, concomitantly, strategic work.

Third, our study elaborates on nascent research into the implications of bodily resources in the strategizing process (e.g. LeBaron and Whittington, 2011; Liu and Maitlis, 2014). For instance, Hodgkinson and Wright (2002) illustrated how a CEO sabotaged a scenario planning meeting through her bodily moves and gestures during a strategy workshop. While current studies have shown how gazes and gestures comprise part of the emotional dynamics associated with different types of strategizing (e.g. Liu and Maitlis, 2014), our study illustrates the implication of bodily resources in constructing different spaces for strategic work as well as, in conjunction with other semiotic resources, the fluid shifts between spaces. For instance, averting gaze from face-to-face orientation to quietly looking at the computer screen helps construct the shift from negotiating work to private work. While bodily resources have largely been neglected in empirical research, our study further stresses the need to include bodily orientations in the study of strategic work and its accomplishments. Future research might, for example, address the implication of seating arrangements and the movements of top management team members on the conduct and outcome of a board meeting (see LeBaron and Whittington, 2011) or the embodiment of a firm's strategy in everyday interactions.

Finally, our conceptual framework provides grounds for future research to adopt an explicitly multimodal approach to exploring strategic episodes in more detail, in particular drawing upon the specific traditions of ethno-methodology to further understanding in the strategy-as-practice field (e.g. Goodwin, 2007; Heath, Hindmarsh and Luff, 2010; Kendon, 1990; LeBaron, 2005; Samra-Fredericks, 2003; Streeck, Goodwin and LeBaron, 2011). A multimodal approach could explore the array of semiotic resources and sensory opportunities available to actors in any given moment. In doing so, such research would build upon a growing interest in using video-recordings to examine the multimodal nature of strategizing (LeBaron and Whittington, 2011; Liu and Maitlis, 2014) and address recent calls for research into the materiality of strategy-as-practice (e.g. Dameron, Lê and LeBaron, 2012; Vaara and Whittington, 2012).

Conclusion

In this paper we have developed a conceptual framework for examining the association between, and mutual constitution of, semiotic resources, spaces, strategic work and strategic outcomes. We focused on a particular setting of strategic episodes in the professional services context of reinsurance trading, where reinsurers, as professional actors, have considerable autonomy to enact aspects of their firm's strategy. The conceptual framework may therefore be particularly useful in similar strategy contexts that deal with abstract, knowledge- and relationship-based strategies such as trading, professional advice, branding and reputation (e.g. Fauré and Rouleau, 2011; Løwendahl and Revang, 1998). However, we also suggest that our framework is conceptually valid for other settings of strategic episodes. For example, we expect that different actors will experience different types of material and/or bodily connection as they withdraw from, engage with and influence the flow of strategic planning meetings. Similarly, our findings suggest that actors have an array of semiotic resources with which to advance their agendas, invite other participants to interact with them on strategic work, or bracket themselves out of the strategy meeting in order to pursue their particular interests. These include resources that have had little attention in strategy-as-practice research, such as silence, body and materials.

Our study aimed to contribute to an agenda for research into the way strategic work is shaped by the interplay of multiple semiotic resources; yet, we recognize the limitations of our theorizing. While others may not find the precise strategic work and spaces that we identified such as private work and restricted space – they may find some other space in addition to, or in place of, those we found because the configurations of resources are differently employed – we suggest that such arrangements are liable to be generalizable to multiple contexts in which actors interact in strategic episodes. Board meetings and strategy workshops involve multiple materials and spatial arrangements, including presentations, spreadsheets, tables, seating orders, projector screens and flipcharts, all of which both shape and also provide resources for the bodily, material and conversational interactions between participants. Thus, our findings, while context specific, offer a set of concepts and a framework with which to advance the study of strategic work and spaces.

Footnotes

Appendix: The ‘box’ at the Lloyd's of London trading floor

Interactions between reinsurers and brokers occur every day and are transacted in face-to-face interaction. The routinized activities take place at standardized desks (called ‘boxes’) comprising the trading floor. These desks are organized in a rectangular, compact configuration (see Image 7). The interactions typically take between 2 and 30 minutes, usually around 15 minutes. They are intense, time-constrained interactions which establish the basis for, and shape the outcome of, a reinsurer's decision to allocate capital to any particular deal.

A box on the trading floor

As shown in Image 7, the physical layout of the box situates the interaction between the reinsurer and broker asymmetrically. Reinsurers sit at a dedicated desk in a comfortable office chair whereas the broker sits on a stool without a backrest. The reinsurer's chair and the broker's stool are arranged orthogonally. Hence, a move in bodily position is required to look at one another and establish eye contact. Asymmetry is also represented in the spatial arrangement of the box. While a reinsurer has a large drawer, a fixed phone, a large portable calculator, a fountain pen and a desktop computer placed on the desk, often connected to two screens, the broker is limited to whatever he or she is able to carry into the building. Brokers do not carry laptops or tablets with them. Their most common ‘work-related’ materials are folders of paper files, data disks (DVDs, USB keys), smartphones and pocket calculators. A reinsurer's desk is a confined physical space, which is just about large enough to place an A4 paper in front of the keyboard. Typically, reinsurers have a sweets jar filled with mints portraying the reinsurance firm's name on their desk. The interactions of reinsurers and brokers are thus a salient ‘arrangement’ (Schatzki, 2002) for studying the accomplishment of strategic episodes as actors draw on bodily, material and discursive resources.

Biographies

Paula Jarzabkowski ([email protected]) is a professor of strategic management at Cass Business School, City University London, and an EU Marie Curie Fellow. She received her PhD from Warwick University. Her research takes a practice theory approach to studying strategizing in pluralistic contexts, such as regulated firms, third-sector organizations and financial services. She is particularly experienced in using and extending ethnographic research methods to study organizational and sectoral issues in these contexts.

Gary T. Burke ([email protected]) is a lecturer in strategic management at Aston University, Birmingham. He received his PhD from Aston Business School. His current research focuses on organizational responses to institutional complexity, in particular how organizational members attempt to resolve tensions between divergent logics, practices and identities.

Paul Spee ([email protected]) is a senior lecturer in strategy at The University of Queensland Business School. He received his PhD from Aston Business School. His research interests are underpinned by social practice theory and revolve around exploring the use of artefacts enabling and constraining situated activities.