Negotiating Language, Meaning and Intention: Strategy Infrastructure as the Outcome of Using a Strategy Tool through Transforming Strategy Objects

Abstract

This research examines how managers collectively use strategy tools in local contexts. Building on a practice approach, we argue that the situated use of formal strategy tools is a process of negotiation, materially mediated by provisional strategy objects. We conceptualize strategy tools and objects as having three aspects: language, meaning and intention. Managers use strategy tools successfully if they ultimately create an accepted strategy infrastructure; this final strategy object materializes the (maybe partial) agreement across all three aspects. We theoretically define three processes according to the primary focus of negotiation and illustrate them with empirical vignettes: abstraction/specification, contextualization/de-contextualization and distortion/conformation. We propose a process model of the collective use of strategy tools that integrates the three processes of negotiation and the shifting roles of provisional strategy objects, namely boundary, epistemic and activity. This research thus offers three theoretical contributions. First, it contributes to the material turn of strategy theory by providing a unified conceptualization of strategy tools, objects and infrastructure. Second, the model offers a basis for analyzing how macro-level formal strategy tools get collectively adapted at a micro-level through negotiation processes and transformations of strategy objects. Third, our research explains why some strategy tools are used but their outputs are not.

Introduction

Most literature on strategy tools is rooted in Clark's (1997, p. 417) definition of them as ‘techniques, tools, methods, models, frameworks, approaches and methodologies which are available to support decision making within strategic management’. Strategy tools help managers analyse their environment or organization (Jacobides, 2010; Mintzberg, 1994) and generate knowledge (Grant, 2003; Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006; Wright, Paroutis and Blettner, 2013). In this sense, they are ‘actionable forms of knowledge that strategy research provides to practice’ (Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006, p. 356), including ‘ “conceptual schemas” […] used to assist strategists in generating meaning’ (Wright, Paroutis and Blettner, 2013, p. 96).

Among all strategy tools, institutionalized - or formal - strategy tools are those that ‘codify knowledge about strategy making within structured approaches to strategy analysis’ (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014, p. 2); examples include Porter's Five Forces, SWOT analysis, BCG matrix, strategic planning, BSC. The most frequently taught tools in business schools, they are also the ones most used in organizations (Clark, 1997; Jacobides, 2010; Rigby and Bilodeau, 2013; Stenfors, Tanner and Haapalinna, 2004) and are explicitly designed to provide valuable strategic insights to users. These formalized tools generally reflect a top-down perspective on strategy.

Yet, despite their widespread use, formal strategy tools sometimes fail to provide useful outputs (Hill and Westbrook, 1997; Kasurinen, 2002; Mintzberg, 1994). Understanding why requires micro-level analyses of how managers use them in practice. For example, recent studies focus on situated uses of strategy tools (Jarratt and Stiles, 2010; Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011) and reveal that users adapt tools to their local organizational context (Fassin, 2008; Jarratt and Stiles, 2010; Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002), such that the adaptations may take ‘strategy tools-in-use’ far from institutionalized strategy tools (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002). Yet the processes by which users adapt strategy tools to local contexts remain poorly understood (Gunn and Williams, 2007; Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009; Wright, Paroutis and Blettner, 2013). This study seeks explicitly to answer the following question: how do managers collectively use strategy tools in local settings? Using a strategy tool constitutes a collective knowledge process that typically involves people from different occupations and functions (Jarzabkowski et al., 2013; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009) who might use the tools in different ways. Understanding the situated use of a strategy tool thus means understanding how a group of managers collates their respective individual uses into a collective use and a collective outcome.

From a practice approach (Reckwitz, 2002; Schatzki, Knorr Cetina and Von Savigny, 2001), the collective use of a strategy tool involves enacting a collective local practice. Practices are ‘embodied, materially mediated arrays of human activities centrally organized around shared practical understanding’ (Schatzki, 2001, p. 11, emphasis added). Material objects offer affordances that pattern practices (Leonardi, 2011) and play different roles (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012). Consequently, the collective use of a strategy tool is shaped by the transformation of many successive strategy objects. By strategy object, we mean the material devices that are part of everyday strategy work (Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013) and that represent strategic knowledge (e.g. drafts of strategic plans, intermediate reports). So far, research has focused on either strategy tools or objects, rather than offering a comprehensive view of how strategy objects mediate situated uses of strategy tools. Such a view can add to our knowledge of how local practices of using a strategy tool unfold. In this article we build on a practice approach to explicitly address the roles that objects play during the collective use of a formal strategy tool. We find that this situated use unfolds through three intertwining processes of negotiation, in which objects take different successive roles; it successfully ends when users agree on a final strategy infrastructure (e.g. official strategic plan or mission statement) that can be re-used in subsequent sequences of strategizing.

The outline of the paper is as follows. First, we review strategy literature grounded in the practice turn of social theories to highlight how the practice approach provides insights for understanding the situated and collective uses of strategy tools. Using a strategy tool produces provisional strategy objects whose various roles can be analysed according to Nicolini, Mengis and Swan's (2012) pluralistic framework. In the second section, we build on these insights to refine the definitions of strategy tools and objects. We argue that both have three aspects − language, meaning and intention − that must align with the users' own languages, meanings and intentions. We propose that the effective use of strategy tools constitutes a process of working out, through collective negotiations, disagreements about the languages, meanings and intentions that strategy objects make explicit. A strategy infrastructure represents a possible outcome of this process, characterized by users' (maybe partial) agreement about all three aspects. In the third section, we discuss − and illustrate with empirical vignettes from the strategy literature − three processes by which users negotiate agreements: specification/abstraction of language, contextualization/de-contextualization of meaning, and distortion/conformation of intention. Each process is associated with a primary focus of negotiation and a particular role for strategy objects. In the last section, we propose a process model of strategy infrastructure emergence that encompasses the interactions of the three processes of negotiation. In addition, we discuss the varying roles of strategy objects and reasons for possible failures of strategy tool use. We also highlight our contributions and avenues for future research.

Our study brings three main contributions. First, it contributes to the material turn of strategy theory by conceptualizing strategy tools, objects and infrastructures all with three interrelated aspects; language, meaning and intention. Second, it offers a process model of the use of strategy tools to analyse how managers collectively use macro-level formal strategy tools at a micro-level, through processes of negotiation and the transformation of strategy objects. Third, our research explains why some strategy tools are used whilst their outputs are not.

A practice approach to the use of strategy tools

Strategy practices as triplets of language, meaning and intention

The practice approach encompasses a plurality of theories that nevertheless share sufficient commonalities to group them under a common label (Reckwitz, 2002; Schatzki, Knorr Cetina and Von Savigny, 2001). In particular, they all focus on action and knowledge (Reckwitz, 2002) and insist that practices are materially mediated (Knorr Cetina, 2001; Schatzki, 2001). Strategy tools are constituent parts of institutionalized strategy practices (Jarzabkowski, 2004; Whittington, 2003), aimed at creating knowledge. They can be conceptualized as interrelated sets of actions (how and when to use the tool), knowledge (concepts and relationships between concepts), intention (reasons to use the tool) and language (that represents knowledge). For example, the SWOT strategy tool involves actions (listing, prioritizing), interconnected concepts (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats), intention (performing a synthesis to analytically generate recommendations) and a mode of representation (four-box matrix). This conceptualization is consistent with Schatzki's (2001, p. 21) remark that practices are both the ‘source and carrier of meaning, language and normativity’: meaning refers to knowledge, language patterns knowledge representation, and normativity shapes intentions by defining acceptable goals.

Moreover, the practice approach links micro- and macro-levels by conceptualizing human action as embedded in social structures in a non-deterministic way. At the macro-level, a practice is an institutionalized way of doing something. At the micro-level, it is a way of doing something for a reason, while drawing on an idiosyncratic understanding of the world. People enact a practice by adjusting their doings, meanings and intentions through both calculation and imagination (Barnes, 2001; Jarzabkowski, 2004; Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006). Thus, the enactment of a practice by a particular individual at a particular moment in a particular context – i.e. practice-in-use − always differs from the institutionalized practice at the macro-level. A practice approach allows macro-level formal strategy tools to be linked to their local, individual uses. Managers involved in strategy work also represent various occupations and functions, including different academic and professional backgrounds. As such, they are the ‘crossing point’ (Reckwitz, 2002, p. 256) of different practices: occupational, organizational or possibly wider strategy practices. Each user of a strategy tool uses it with specific doings (language), specific interpretations (meaning) and specific purposes (intention).

Varying roles of strategy objects during the use of strategy tools

People carry out practices by using things, or physical devices (Knorr Cetina, 2001; Schatzki, 2001). Things are fully part of the enactment of a practice; they are constrained by and simultaneously constrain actions and knowing (Engeström and Blackler, 2005; Reckwitz, 2002). Leonardi (2011, p. 153) uses the term ‘affordance’ to explain why people use the same physical thing differently: ‘Technologies have material properties, but those material properties afford different possibilities for action based on the contexts in which they are used. […] Affordances are unique to the particular ways in which an actor perceives materiality.’ When people use a strategy tool, they create, transform and withdraw things (Macpherson and Jones, 2008; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009). Some of these things convey meaning and intention. For example, when doing a SWOT analysis, one uses things (e.g. pen, personal computer) to make successive drafts (Giraudeau, 2008) that represent the knowledge that one fills the SWOT concepts with. Drafts have particular status, because they embed some of the knowledge being produced and depend on the concepts and interrelations provided by the SWOT strategy tool. In this sense, drafts are strategy objects that embed and represent some of the knowledge and intention used in strategy work. In their study of re-insurance underwriting managers who assess the risk of insurance deals, Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets (2013) demonstrate that strategizing activities embrace successive uses and transformations of strategy objects, such as photos, maps and spreadsheets. They associate each type of object with a particular practice, as well as with a specific meaning and intention. For example, the strategy objects used in the practice of ‘physicalizing’ are photos that convey knowledge about what is to be re-insured, provide ‘a sense of what is actually insured’ and convey underwriting managers’ intentions of ‘familiarizing [themselves] with the type and structures of the properties that comprise the deal’ (Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013, pp. 46−47, emphasis added).

Regarding the collective use of strategy tools, provisional strategy objects make some of the individual users' perceptions of affordance explicit and thus highlight that they must collectively align their languages, meanings and intentions. In a study of virtual project networks, Alin, Iorio and Taylor (2013) show that digital objects facilitate negotiations by structuring knowledge (meaning); making knowledge visual, concrete and focused (language); and facilitating collective conformation with a rationale for use (intention). This process of negotiating languages, meanings and intentions involves strategy objects that change roles according to the focus of the negotiation. Nicolini, Mengis and Swan (2012) argue that four complementary theories (boundary, epistemic, activity, and infrastructure objects) can explain these changing roles of objects.

Boundary objects support collaborations among people from different groups and with different backgrounds; they ‘have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable’ (Star and Griesemer, 1989, p. 393). Using a boundary object thus implies that a common language is being negotiated, and the knowledge it embeds may differ without altering the object (Star, 2010; Star and Griesemer, 1989).

Epistemic objects represent the purpose of collective activities. People collaborate to build physical objects about whose knowledge content they agree. During collaboration, they strive to materialize the epistemic object in provisional objects, creating new knowledge in the process. The process is nevertheless driven by a common intention that some knowledge must be created, and the epistemic object is a valuable goal.

Activity objects are the locus for the confrontation of multiple, potentially divergent perceptions of what they should be and their role in the group. They are ‘a “problem space” into which actors bring various skills and conceptual tools to negotiate the object(ive)’ (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012, p. 621, emphasis added). This negotiation process probably generates conflicts and power games, which result in the evolution of the activity object.

Infrastructure objects are unproblematic parts of everyday activities, such as telephones or computers. They are embedded in practices (Star, 2010; Star and Ruhleder, 1996) and embed past learning and accepted knowledge (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012). Moreover, they are deemed legitimate enough to be made official and diffused outside the group (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012; Stigliani and Ravasi, 2012).

Research gap

Our literature review demonstrates that the use of a strategy tool is a process of collaborative knowledge work that involves various strategy objects. Accordingly, our research question regarding how managers collectively use strategy tools in their local settings leads us to consider strategy tools and objects jointly.

Although prior literature on material strategizing is rich and vivid, most studies focus on either objects (e.g. Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013; Kaplan, 2011; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011) or strategy tools (e.g. Gunn and Williams, 2007; Jarratt and Stiles, 2010; Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014). To the best of our knowledge, no study directly addresses both concepts. For example, Jarratt and Stiles (2010) note that strategy tools get used differently depending on local settings, but they do not reflect on the specific objects crafted and used in relation to those tools. Scholars who examine how some objects provide a basis for strategy work do not explicitly link them to strategy tools. For example, Kaplan's (2011) thorough analysis of the role of PowerPoint in investment approvals does not connect it to a particular strategy tool.

Yet linking the concepts is necessary to understand how formal strategy tools are effectively used in collective local strategizing. Anyone involved in strategy work has a specific way of using a strategy tool, with specific language, meaning and intention, all of which are interrelated aspects of a same strategy practice. However strategy work in organizations is usually a collective exercise, involving people with various strategy practices. Thus, using a strategy tool means aligning it with the users' own and varied languages, meanings and intentions, so that they can produce a common analysis of their business or environment. During this process, strategy objects make explicit the users' languages, meanings and intentions, and they materialize agreements and disagreements. They are persistent (Stigliani and Ravasi, 2012; Vyas, Heylen and Nijholt, 2008) and cannot easily be discarded. We thus consider strategy objects when studying the use of strategy tools, to properly integrate individual agency.

Strategy infrastructure as the outcome of using a strategy tool

Three aspects of strategy tools and objects

We build on the practice approach and Leonardi's (2011) distinction between the material properties of objects and their varying affordances to propose that strategy tools and strategy objects are both characterized by three interacting aspects: language, meaning and intention. By doing so, we also refine the recent distinction by Jarzabkowski and Kaplan (2014) between material and conceptual affordances by splitting the conceptual aspect into meaning and intention. This refinement allows us to distinguish analytically between know-what and know-why.

Language reflects a way to represent meaning and intention. In the case of strategy tools, it is linked to modes of knowledge representation (e.g. graphs, matrices, flow charts) and labels (i.e. concepts' names). For strategy objects, it refers to their physical appearance: a combination of signs and symbols inscripted on a physical medium1 that makes some of the meaning and intention aspects explicit.

Meaning refers to the knowledge that strategy tools and objects convey, which is only partially represented through language. ‘Meaning’ embeds two types of knowledge: conceptual (concepts' definition and their relationships) and factual (concept instantiations). People with different backgrounds may understand concepts differently, such that the same factual knowledge results in distinct interpretations. Strategy tools convey academic knowledge to practitioners (Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006), in which case ‘meaning’ refers to conceptual strategy knowledge. Objects embed knowledge too (Bechky, 2003; Eweinstein and Whyte, 2009), in which case ‘meaning’ encompasses users' factual and conceptual strategy knowledge. For example, someone doing a SWOT analysis selects items that reflect his or her own perception of the company's strengths and weaknesses, according to his or her understanding of what a strength or weakness is.

Intention refers to the reason for using a strategy tool or object. Strategy tools embed assumptions about the reasons and contexts for their use, as well as premises about firms and strategy processes (Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002; Mintzberg, 1994; Moisander and Stenfors, 2009). For example, strategic planning conveys a top-down approach to strategy formulation, in which the strategy should be formulated before being executed (Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002; Mintzberg, 1994). Strategy objects convey their user's idiosyncratic vision of the organization and rationale for using them. This intention may differ from the intention embedded in the strategy tool and be linked instead to individual agendas or perceptions of how the organization should operate (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014). For example, Grant (2003) shows that oil companies' strategic plans served to foster collaboration between decentralized business levels rather than to formulate ex ante corporate strategies.

Table 1 illustrates the three aspects of strategy tools and objects for a SWOT analysis. It is based on Hill and Westbrook's (1997) analysis of how 20 companies implemented a SWOT strategy tool, in which they show that its collective situated use differed from textbook recommendations. We use their initial description of the academic, formal SWOT strategy tool to represent the ‘SWOT as a strategy tool’ column and their empirical results for the ‘SWOT as a strategy object’ column.

| SWOT as a strategy tool | SWOT as strategy objects | |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Four closely related boxes; 3–4 items per box | Four boxes, average of 40 items per SWOT, ranging from 11 to 216 items |

| Meaning |

Strengths, weaknesses, … One item cannot be strength and weakness simultaneously |

Same items listed as strengths and weaknesses or strengths and opportunities |

| Intention |

Rational way to analyse Generating strategy recommendations |

Way of initiating discussion across divisions Way of complying with hierarchical desires |

The three aspects are interrelated. Both meaning and intention inform the language aspect, and vice versa: the language aspect makes partially explicit the content of the other two, and it patterns intent and knowing without fully determining them (Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013; Leonardi, 2011). Fassin (2008) shows that the usual graphical representation of a stakeholder model, with equal circles for all stakeholders, leads users to assume equal weights of stakes and powers for all of them, for example.

Definition of strategy infrastructure

The effective, collective use of a strategy tool entails a process of working out disagreements about languages, meanings and intentions, which strategy objects make explicit. We label strategy infrastructure the possible outcome of this process, i.e. a final strategy object that represents accepted strategic knowledge and that embeds language, meaning and intention for which users have established a collective agreement. Its language aspect consists of an accepted physical form that represents strategy knowledge; its meaning aspect conveys strategy knowledge that has been collectively generated and/or accepted by users of the strategy tool; and its intention aspect embeds this situated agreement about how, why and when the strategy infrastructure should be used during subsequent strategizing.

Sufficient agreement on all three aspects occurs when users agree to make the final strategy infrastructure official. This means that users believe the strategy infrastructure will satisfy internal or external clients and that a consensus decision has been reached. Kaplan and Orlikowski (2013) label this decision a provisional settlement; Jarzabkowski and Kaplan (2014) call it an interim decision. Whittington et al. (2006) give the example of three successive cubes that represent critical elements of a firm's strategy. Cubes emerged from strategizing sequences and then were diffused in the organization as an official device: ‘Seven-sided cubes could often be seen on office desks and were used in meetings as a reference point for discussion’ (p. 623). Because a strategy infrastructure is ‘official’ and materializes agreement about language, meaning and intention, users adopt it as a reference point for subsequent strategizing. This agreement might be provisional; it is still stable enough to provide a basis for moving forward in a strategizing process (Kaplan and Orlikowski, 2013).

Therefore, for users, the strategy infrastructure plays the role of a material infrastructure object (Star and Ruhleder, 1996) that will be used during subsequent strategizing. It has become ‘an unproblematic means to an end rather than an independent thing to which [users] stand’ (Knorr Cetina, 2001, p. 187). Furthermore, it is the outcome of a collective agreement rather than the result of an individual use of a strategy tool. It differs from boundary objects, because it goes beyond providing a unified language, and from epistemic and activity objects, because it encompasses agreements on meaning and intention. Finally, not all things that are part of the material infrastructure of strategy work are strategy infrastructure. As per our definition, an additional condition is the symbolic representation of strategic knowledge.

Table 2 synthesizes the respective language, meaning and intention aspects of strategy tool, objects and infrastructure. It rests on the idea that the situated use of a formal strategy tool relies on the individual and/or collective use of many successive strategy objects with different roles. These objects eventually lead to a strategy infrastructure, once most of the group has agreed on the boundaries of language, meaning and intention. The strategy infrastructure is the collective outcome of the group's use of a strategy tool.

| Strategy tool | Strategy objects | Strategy infrastructure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Modes of knowledge representation and labelling |

Physical appearance Combination of signs and symbols inscribed on a physical medium |

Accepted physical form representing strategy knowledge |

| Meaning | Conceptual knowledge (strategy concepts' definition and relationships) | Users' factual and conceptual strategy knowledge | Accepted collective strategy knowledge |

| Intention |

Premises about firms and strategy processes Assumptions about reasons and contexts for use |

Users' idiosyncratic perceptions of how the organization should operate Rationale for use (including individual agenda) |

Situated agreement on how, why and when the strategy infrastructure should be used in subsequent strategizing |

In Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets's (2013) study, re-insurance underwriting managers use a collection of strategy objects (photos, maps, spreadsheets) to incorporate their individual knowledge in a final curve. The different curves ultimately get collated in a final Excel graph used for collective decision making. Managers agree that this final graph is the best way to incorporate their respective strategic knowledge. That is, they have reached agreement about the graph's language (curves and graph), meaning (what is a risk) and intention (making rational decisions so that the company has a well-performing portfolio). Photos and spreadsheets are not strategy infrastructures because they neither are collectively used nor embed collective knowledge. However, they transform into a strategy infrastructure − the final (collective) graph, with all the curves − that serves as an unproblematic device to support subsequent strategizing sequences, including the selection of re-insurance deals.

Three processes of language, meaning and intention negotiations

Because a strategy tool is abstract and de-contextualized enough to adapt to different contexts (Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009; Stenfors and Tanner, 2007), it is not immediately suited to the users' local context. Its situated use demands an adaptation process that unfolds through provisional strategy objects. These objects are the locus of partial agreement; the knowledge and intention they convey and represent are well suited for some but not all users. They mediate negotiations because they act as propositions from some users, which cannot be discarded because they are ‘persistent forms of information’ (Vyas, Heylen and Nijholt, 2008, p. 330). Through negotiations, users may or may not reach agreement on language, meaning and intention and succeed in creating a strategy infrastructure. Therefore, a strategy infrastructure results from three interrelated processes of collective negotiation of language, meaning and intention, during which provisional strategy objects take different roles (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012).

Differentiating the processes according to their primary focus of negotiation is a prerequisite analytical step, before we can discuss their interrelations in the ‘real’ trajectories of using a strategy tool. We therefore present three processes, according to the primary focus of negotiations and corresponding to a specific role for provisional strategy objects. We illustrate these processes with empirical vignettes, based on secondary data from past research.

Process 1: Boundary object – negotiating language through abstraction and specification

The first process focuses on how to represent knowledge and thus on the language aspect. It is oriented toward working out knowledge representation problems. A strategy tool comes with ‘strategy language’ (Loeweinstein, 2014; Mantere, 2013) that is largely disseminated outside the strategy profession (Balogun et al., 2014). The way managers understand and use strategy language may differ from ‘strategy professionals' use’ (Mantere, 2013) and vary across professional and organizational groups (Nicolai and Dautwiz, 2010). Even if they all agree about using a specific strategy tool (e.g. balanced scorecards), users might not agree on labels or modes of representation (e.g. changing the perspectives' names and positions; Chesley and Wenger, 1999).

When users of a strategy tool encounter language problems, they probably create, use and/or transform provisional strategy objects to allow discussions of language. These strategy objects thus act as boundary objects. The succession of provisional objects in turn helps users reach a collective agreement about the language they will retain for the final strategy infrastructure.

Agreeing the language aspect is an iterative process of abstraction and specification. To be used in strategizing activities, a strategy tool must be specified (i.e. de-abstracted) in a physical form. Specification implies that users experiment with and discuss successive physical forms and labels. In several rounds of collective object design, users create drafts to represent their own knowledge and the knowledge they create during the process (Eweinstein and Whyte, 2009). These drafts are provisional strategy objects that can be retained or dropped in each successive sequence; users retain the drafts that invoke at least partial agreements. Such agreements mostly occur due to abstraction. Abstraction entails the use of general rather than specific words (Jarzabkowski, Spee and Smets, 2013) and/or unquestioningly juxtaposing diverging items, so that any user can find something suitable (Hill and Westbrook, 1997).

The final draft retained as strategy infrastructure thus conveys more abstract language than the provisional strategy objects and is more specified than the formal strategy tool. This intermediate level of abstraction provides enough interpretive flexibility to allow users to agree on the language used to represent knowledge. At the same time, it keeps the strategy infrastructure recognizable, as a legitimate, acceptable adaptation of the strategy tool. Macpherson and Jones (2008) give a detailed account of language negotiation during the use of a SWOT analysis tool (Vignette 1).

Vignette . Vignette 1. SWOT analysis as a boundary object: Negotiation of language

Macpherson and Jones (2008) describe the use of a SWOT analysis at PresMed, a medium-sized company. Because of important financial difficulties, its new CEO decided to renew the organization's strategy and hired two strategy scholars as consultants. All three decided to start with a SWOT analysis. The consultants first conducted individual sessions with nine managers from different functions and of various expertises and helped them build nine individual SWOT analyses. Then, they gathered the CEO and the functional managers together in a roundtable session and showed them the different SWOTs. Next, they presented their common points in a provisional collective SWOT. The ensuing discussion focused on the selection of five priority items per category, ending with a final SWOT document that served in a subsequent phase to constitute workgroups focused on enhancing strengths or solving weaknesses. It acted as a strategy infrastructure.

Neither the rationale for using SWOT analysis nor the need to align meaning was the focus of negotiation. From the beginning, the use of SWOT analysis remained unquestioned, and all managers agreed that ‘as individuals we may have extreme views but as a group we all realize that, sort of, we have to give a little − find the middle-ground’ (p. 187). The initial SWOTs contained 107 items that represented the nine managers' respective knowledge. They acted as boundary objects (repository) that evidenced diverging knowledge among functional directors: ‘there was remarkably little agreement among the team about any of the four elements. There were points of conflict between the production manager, the sales manager and the head of purchasing’ (p. 187).

To build the provisional collective SWOT, the consultants grouped some items together through abstraction. For example, in the ‘opportunities’ box of the provisional SWOT, they abstracted items such as ‘Russia’, ‘US market’, ‘new dealers’, ‘Far East’ and ‘export growth’ under the sole label ‘new markets’. The types and locations of possible markets were lost, and the use of more abstract terms facilitated agreements among managers from different functions. Thus, the provisional collective SWOT was a boundary object too. The discussion during the roundtable session led to the addition of new items. The next SWOT had 14 items, and the final one contained 20. Thus, some specification was reintroduced, through discussions about which items would best suit. ‘New market’ was split again into ‘market share’ (market penetration) and ‘market diversification’, for example. The two consultants framed the evolution of the language aspect according to the formal SWOT strategy tool: the final strategy infrastructure ended with five prioritized items per box.

Process 2: Epistemic object, negotiating meaning through contextualization and de-contextualization

Users also try to reach an agreement on the meaning incorporated in and conveyed by the final strategy infrastructure. This process occurs when they focus on the problem of knowledge generation (meaning aspect). If users of a strategy tool encounter meaning problems, they probably create, use and transform strategy objects that allow discussions of meaning. When users negotiate meaning, the future strategy infrastructure becomes an epistemic object, i.e. an ‘object of investigation that is in the process of being materially defined’ (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012, p. 618). Users materialize it through successive provisional strategy objects (Eweinstein and Whyte, 2009), which help converge toward an agreement on meaning.

Agreeing on the meaning aspect is an iterative process of contextualization and de-contextualization. Successive drafts make explicit the meaning aspect of the strategy tool, which probably differs from users' knowledge (Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006). Thus, users need to contextualize the strategy tool's meaning (Aggerholm, Asmuß and Thomsen, 2012; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011). Contextualization means adapting the strategy tool to the local context by instantiating concepts with factual knowledge. However, contextualization through provisional strategy objects leads users to make their different understandings explicit, such that it highlights discrepancies. Thus, users need to negotiate agreements on meaning, typically through mutual interactions and collaborative sensemaking, that progressively restrain the range of re-interpretations. The process ends when (partial) agreement is reached. This agreement creates a boundary that delimits the range of the strategy infrastructure's meaning because it focuses the group's attention on some aspects of strategy to the detriment of others, and it discards knowledge that is considered unimportant. In this way, it implies some de-contextualization of meaning (Aggerholm, Asmuß and Thomsen, 2012; Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2011), which is a necessary loss because it makes the strategy infrastructure more ambiguous and available for re-use in different situations (Abdallah and Langley, 2014; Jarzabkowski, Sillince and Shaw, 2010; Nicolai and Dautwiz, 2010). Eventually, the strategy infrastructure reaches an intermediate level of contextualization, because too much de-contextualization and ambiguity might foster struggles in subsequent strategizing (Abdallah and Langley, 2014), but too much contextualization impedes the settlement on a final agreement. Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) provide a detailed account of such a contextualization/de-contextualization process (see Vignette 2).

Vignette . Vignette 2. Strategic planning as an epistemic object: Negotiation of meaning

In an ethnographic case study at Unico University, Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) describe how academics from different disciplines collaborated to build a strategic plan for their university. The collaboration process went back and forth between oral conversations and textual inscriptions, with a progressive fixation on a final strategic plan, which was then communicated to the whole university as a strategy infrastructure. The process allowed academics to infuse 11 successive documents with their different knowledge. Those documents were provisional drafts materializing the epistemic object, ‘final strategic plan’.

The use of the strategic planning tool was initiated by a newly appointed vice chancellor. However, there was agreement at Unico about the need to develop a new strategic plan − the intention aspect was not controversial. Nor was language, because ‘Unico's strategic plan followed a typical planning structure […], consisting of a vision, mission statements, strategic objectives and key performance indicators’ (p. 1223). Discussions mainly focused on meaning.

In building the strategic plan, the talks and meetings involved groups of users from various academic disciplines and professional communities, ‘to make sure that at the senior level across the heads … we have a reasonably common understanding of what we mean by some of the phrases’ (p. 1232, emphasis added). This negotiation of meaning operated through de-contextualization: users would incorporate meaning into provisional drafts of the strategy plan. The drafts had ‘disciplining effects during conversations, in particular […] the structure and content of Unico's plan disciplines the order and the general topics of talk’ (p. 1227). The meaning they conveyed could not be traced back to their author and it applied to different contexts. During meetings, though, users would re-contextualize the meaning conveyed by drafts. Contextualization would help them put forward their own understanding of the university's strategy or a particular point they considered important. It would also generate meaning negotiations: ‘where it says “where appropriate commercialize the results”, is it just where appropriate or should we be encouraging people to focus their research into areas that can be commercialized?’ (p. 1228).

Negotiations of meaning progressively reduced the range of variation between provisional strategy objects until they converged in an accepted strategy infrastructure: ‘At later stages of the production cycle, in particular period 5, it was more difficult for participants to trigger content changes, as the plan was already considered to carry meaningful statements’ (p. 1236). Convergence was framed by referring to the strategic planning tool's institutionalized structure: ‘The VC's question about measuring was triggered by the previous planning period's guiding question which had focused on how Unico could measure specific actions, and had already resulted in amendments to the strategic plan. As Departmental Head C could not provide an immediate answer, the VC blocked the suggestion, and it did not lead to a content change in Unico's strategic plan’ (p. 1233).

Process 3: Activity object, negotiating intention through distortion and conformation

The third process occurs when at least some of the users challenge the strategy tool's intention aspect. Strategy tools convey assumptions about the reasons for their use and the context in which they are to be used. Simultaneously, users have their own respective agenda and assumptions about the organizational context (Jarzabkowski, 2004; Kasurinen, 2002; Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002). When using a strategy tool, they make these explicit through provisional strategy objects (Kaplan, 2011; Kaplan and Orlikowski, 2013) that act as ‘triggers of contradictions and negotiations’ (Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012, p. 621). Therefore, the future strategy infrastructure is an activity object whose emergence depends on users' ability to negotiate a common intention.

Agreeing on the intention aspect is an iterative process of distortion and conformation. Users build provisional strategy objects based on their intentions − whether linked to their own agenda or assumptions about how the organization operates. They distort the strategy tool's intention (Aggerholm, Asmuß and Thomsen, 2012; Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002), in that the strategy tool is ‘captured and used to reproduce existing roles and power structures’ (Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002, p. 540). Kasurinen (2002) describes how managers of a metals group's business unit distorted the rationale behind the balanced scorecard: they did not present a well-defined strategy for the future, yet they developed diagnostic non-financial performance measures.

Conversely, when a strategy tool is collectively used, users also need to negotiate an agreement about the strategy infrastructure's intention, to which they will conform. The successive strategy objects allow for compromising on, retaining or ignoring some users' intentions. Some conformation of intention thus occurs, in that users agree a normative way to use the infrastructure, even if they do not fully agree the rationale behind it. They might build a surface consensus − provisionally agreeing to conform. Kaplan (2011) shows how two project leaders and a marketing team mobilized PowerPoint strategy objects ‘in political efforts to adjudicate competing interests’ (p. 332) and to force other users to conform to the dominant rationale.

The process ends when users reach a situated agreement about how and when the final strategy infrastructure should be used in subsequent strategizing. The intention does not necessarily suit all users' agendas or perfectly reflect the formal strategy tool's assumptions. Lozeau, Langley and Denis (2002) present such a process in the context of Canadian hospitals (Vignette 3).

Vignette 1. Vignette 3. Strategic planning as an activity object: Negotiation of intention

Lozeau, Langley and Denis's (2002) analysis is based on cross-sectional data from 33 hospitals. Responding to external pressures from their wider organizational context, the hospitals had to implement the strategic tool ‘Strategic Planning’. In nearly all cases, the strategy tool was distorted, i.e. used with an intention that differed from the institutionalized rationale of strategic planning. Twenty-six hospitals succeeded in adopting strategic planning and created a strategy infrastructure, published as the official strategic plan and later used as a reference for dealing with external stakeholders.

In the 26 hospitals, implementation processes involved physicians, CEOs and consultants in charge of environmental diagnoses. Their initial intentions differed: physicians conveyed their own professional logic, whereas the CEOs and consultants' intentions were closer to the tool's intention aspect. Although objective data were gathered and discussed, ‘political negotiations tended to predominate’ (p. 548). In some cases, a coalition between professionals and CEOs allowed the emergence of a final consensus to which users would conform: ‘professionals and administrators were able to get together to debate issues and to build some solidarity around the promotion of the organization with government’ (p. 548). In other cases, either the CEO or the professionals took advantage from the others' weaknesses and promoted their own agenda to which the others had to conform: ‘The CEO was able to ensure implementation of his plan with the help of a consultant, a physician administrator and the Board. [He] behaved in a way consistent with the assumptions of the traditional planning model [and succeeded] because of the extreme weakness of the physicians’ (p. 549).

These processes of negotiation led to some distortion from the formal strategy tool's intention. Professionals negotiated intention to match their own agenda and vision of the hospitals through exercising their considerable power during the building of the strategic plan: ‘Among our respondents, 54 percent said that professionals' opinions counted more than analysis, 31 percent said analysis and opinions were equally weighted and only 14 percent felt that analysis dominated’ (p. 548).

Ultimately, the intention inscribed in the final strategic plan was very specific and oriented toward external stakeholders rather than insiders: ‘[The strategic plan] becomes yet another tool of influence for managers and professionals […] rather than a path to “rational” strategic choice’ (p. 548). Although distortion occurred, the final strategy infrastructure still looked like a ‘formal’ strategic plan, to meet external stakeholders' will.

Discussion, contributions and avenues for future research

A process model of the use of strategy tools

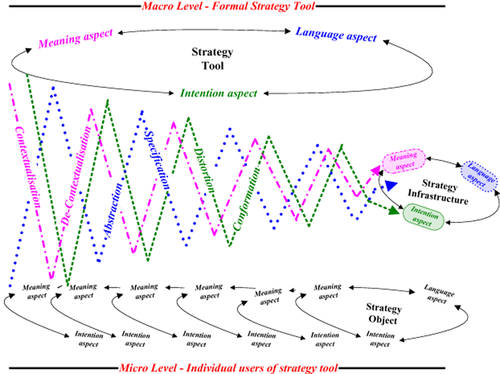

As shown in Figure 1, the collective use of a strategy tool implies negotiations (materialized through provisional strategy objects) that allow adaptation to the local context. These provisional strategy objects are less specific to individual users and thus can suit all users' needs. The formal strategy tool frames negotiations throughout the process by providing a collective reference point. There are three types of negotiation associated with the three aspects of strategy tools and objects, represented by each dotted arrow. They imply different tactics according to the aspect on which they focus: abstraction/specification of language, contextualization/de-contextualization of meaning, and distortion/conformation of intention. The three processes of negotiation intertwine, and the use of a strategy tool actually unfolds through a plurality of trajectories which focus alternatively on each aspect of negotiation, depending on who is involved and how the process evolves. For example, contextualization of meaning may trigger negotiations of intention or language: difficulties during knowledge discussions may make people acknowledge that their intentions differ or that they do not assign similar meanings to common words. Depending on the initial sharing of meaning or intention, some abstraction is also required to agree on the language aspect. Lozeau, Langley and Denis (2002, p. 547) stress that physicians increased abstractness of their final strategic plan. Spee and Jarzabkowski (2011) describe how two managers used a similar tactic to solve disagreements about Unico's research mission. Specification or abstraction of language also leads to adaptations of the other aspects. If no adaptation occurs, provisional strategy objects only act as boundary objects: their transformation into an accepted strategy infrastructure demands further collective sensemaking and conformation, and thus an evolution of their meaning and intention. Finally, strategy infrastructures (right side of Figure 1) result from the use of a strategy tool through transformations of strategy objects. They emerge as the outcome of the three intertwined negotiation processes that help users converge (as shown by the dotted arrows) toward an agreement on boundaries of language, meaning and intention.

Strategy infrastructure resulting from the use of a strategy tool, through transformation of strategy objects

Our model shows that strategy infrastructures are the outcome of ‘strategy tools-in-use’ (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014), i.e. of the adaptation process that unfolds during the use of strategy tools. We contribute to prior research by showing that adaptation entails the negotiation of the language, meaning and intention conveyed by the strategy tool, to make these compliant with the local languages, meanings and intentions of users. Our research suggests that managerial discretion might affect the use of strategy tools by influencing the primary focus of negotiation. To complete our understanding, further empirical research could study the kind of trajectories (e.g. successive shifts across language, meaning and intention negotiations) that occur in diverse settings. We also need to explore whether and in what conditions and contexts some trajectories are more effective than others for producing strategy infrastructures. The role of individual agency in selecting tactics for using strategy tools, such as abstracting, contextualizing or distorting, needs further consideration too.

The shifting roles of objects in the use of strategy tools

These successive and interrelated processes of negotiation rely on provisional strategy objects. Our model associates the primary focus of negotiation not only with specific processes (as shown in Figure 1) but also with the role that strategy objects take (see Table 3). If the focus of negotiation is intention, the future strategy infrastructure and the provisional strategy objects are activity objects that make disagreements explicit. If the focus is language, strategy objects serve as boundary objects. Finally, if negotiation focuses on meaning, the strategy infrastructure becomes an epistemic object, and strategy objects are its physical materializations. Therefore, the use of a strategy tool implies alternative uses of boundary, epistemic and activity objects, which might result in a strategy infrastructure. For example, Kaplan (2011) shows how a PowerPoint template used for investment approvals evolved from a boundary object designed to collate inputs from different functions into an activity object that became the focus for harsh negotiations of power and intention. Through negotiations, the presentation became a final accepted infrastructure document, officially sent to a review board for approval.

Our model contributes to a holistic theory of the collective use of strategy tools by including integrative strategizing (boundary objects to support the development of a common strategy language across functions), strategy knowledge creation (epistemic objects to support sensemaking) and rationalization (activity objects that mediate the actual rationale or intentions for using a strategy tool).2 Moreover, it refines strategy objects' roles by associating each with a specific focus and process of negotiation. In doing so, our research complements current studies on material strategizing by considering strategy tools and objects jointly. It highlights that users' agency, during the use of a strategy tool, is materially mediated by strategy objects that make the respective languages, knowledge and intentions explicit. Users adapt objects to their local settings while keeping some resemblance with the formal strategy tool, in order to benefit from the appearance of rationality that the latter confers. Our research suggests that organizations might benefit from an informed use of strategy objects since individual agency influences their evolution. More research is thus needed to deepen our understanding of how users pattern the use of strategy tools, by choosing or changing the primary focus of negotiation and triggering changes in strategy objects' roles.

Explaining the success or failure of the use of strategy tools

Our model offers insights into why formal strategy tools, though widely taught and used, sometimes succeed, sometimes do not, and sometimes only provisionally do. In line with a practice approach, the successful use of a strategy tool does not necessarily require strict adherence to the formal strategy tool, nor does it relate to the generation of accurate knowledge (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Lozeau, Langley and Denis, 2002). An effective use rather implies the ability of users to collectively produce an accepted, stable outcome, in the form of a strategy infrastructure. This strategy infrastructure materializes their (partial) agreements about strategy language, meaning and intention. With this definition, we account for the creative use or re-invention of formal strategy tools in local contexts (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014; Jarzabkowski and Wilson, 2006).

Still, the complexity and intertwining of the negotiation processes imply that users may be unable to build sufficient agreement, and that strategy infrastructures are not ineluctable outcomes of the use of strategy tools. Hill and Westbrook (1997) note that, of the 25 SWOT analyses in their study, only three were re-used as a basis for further strategizing. Our model suggests that the final SWOT did not emerge as an accepted strategy infrastructure: too much abstraction on the language aspect hindered the evolution of meaning and intention.

Our conceptualization of strategy infrastructures as material infrastructure objects also implies that they might return to boundary, epistemic or activity objects during subsequent strategizing (Kaplan and Orlikowski, 2013; Nicolini, Mengis and Swan, 2012) when, for example, a crisis generates an explicit disagreement about a previously accepted meaning, intention or language. Such crises are not ineluctable though, because of the interpretive flexibility that the strategy infrastructure achieved through abstraction, de-contextualization and conformation. Strategy infrastructure consumption means re-interpretations (Abdallah and Langley, 2014; Aggerholm, Asmuß and Thomsen, 2012; Kaplan and Orlikowski, 2013). These re-interpretations are part of usual strategizing practices, for which the strategy infrastructure acts as the template to which practitioners refer.

Conclusion

This research proposes a process model of how managers collectively use strategy tools in their local settings. With a practice approach, we show that managers succeed in using a strategy tool when they eventually create an accepted strategy infrastructure, which is a final strategy object that materializes (partial) agreements. Asserting that strategy tools, objects and infrastructures all have three interrelated aspects − language, meaning and intention − we suggest that negotiations focus on these and respectively imply processes of specification/abstraction, contextualization/de-contextualization and distortion/conformation. We build on Nicolini, Mengis and Swan's (2012) framework to show that, during negotiations, strategy objects take different roles, depending on the primary focus of negotiation.

Thus, our research offers three main contributions. We add to the material turn in strategy theory by providing a unified conceptualization of strategy tools, objects and infrastructures. With this conceptualization, researchers can account for the situated nature of the material things that people use during strategizing; it also provides a basis for linking strategy tools and objects. Our research also provides a process model that explains why and how strategy tools-in-use differ from institutionalized strategy tools (Jarzabkowski and Kaplan, 2014), namely because of three intertwining negotiation processes between users. Our model also explains the shifting roles of strategy objects (boundary, epistemic and activity) that materialize negotiations. Finally, our research suggests that strategy tools fail because of their users' inability to reach agreement about boundaries of language, meaning or intention. These contributions in turn call for future research into the plurality of trajectories by which strategy infrastructures emerge and how users' agency can shift strategy objects' roles and frame negotiations.

Footnotes

Biographies

Caroline Sargis-Roussel is Associate Professor and Director of Academic Development and Quality at IESEG School of Management. Her research interests are knowledge management, management control systems, implementation of strategy tools, social capital and routines in cross-functional teams.

Cécile Belmondo is Assistant Professor at IAE Lille - University of Lille 1 and a researcher in the LEM research center (UMR CNRS 8179). Her research interests are knowledge management, attention management, the practice and processes of strategic knowledge creation, and of routine emergence at the group level.