Does Tourism Promote Cross-Border Trade?

The authors thank two anonymous referees for helpful suggestions. Any remaining errors are the authors'. Funding was provided by the Arizona-Mexico Commission. Senior authorship is not assigned.

Abstract

We estimate a simultaneous bivariate qualitative choice model of Arizona agribusiness firms' propensity to trade and visit as a tourist the cross-border state of Sonora, Mexico. Venture business visits, quantified through the tourism equation, were found to have the largest impact on a firm's propensity to trade. Tourist visits have a greater impact on trade when combined with other firm attributes such as age, perceived need for geographic diversity, foreign language fluency, and firm size, than if considered alone. Our results suggest that there is a role for government agencies to play in overcoming imperfect information related to trade opportunities through facilitating exploratory business venture and tourist visits.

Implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on 1 January 1994 was accompanied with high publicity and expectations of a much brighter future for expanding trade of agricultural products. Indeed, food and agricultural trade among NAFTA countries has grown remarkably, particularly between the United States and Mexico. In spite of transportation bottlenecks, trade activity between Mexico and the United States has more than doubled for agriculture in the last decade, increasing from a pre-NAFTA level of $5.2 billion in 1990 to a post-NAFTA level of $11.5 billion by 2000 (USDA, FATUS: Foreign Agricultural Trade of the US). This growth in trade is faster than what has occurred between the United States and other developed foreign markets such as Japan, Taiwan, and the European Union (Coyle). While much of the U.S.-Mexico trade has been generated by states along the border, some border states and communities have fared better than others in attracting cross-border trading activities (Business Frontier, Pavlakovich-Kochi, Pavlakovich-Kochi and Sonnett, Erie and Nathanson, Schliesman, Walker and Morehouse). In addition, many regional organizations, states, and communities have pursued activities and projects (e.g., publications, trade shows, tours) with the intent to attract more trade and economic activity to their locations. For example, the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas is launching a new ongoing publication series entitled “The Border Economy” to focus on Texas-Mexico border economic issues. Our analysis addresses the kinds of firms, policies, and activities, including tourism and venture visits, that could be targeted in order to attract more regional trade.

Many states have expressed great interest in tourism and related recreation activities as a way to increase and diversify their economic base, particularly in rural areas (Fawson, Thilmany, and Keith). While tourism has direct, indirect, and induced impacts on economic development (Slee, Farr, and Snowdon), it may also have a more subtle impact on economic activity by influencing a firm's propensity to trade. A recent literature survey of tourism and economic development postulates that tourism could help mitigate market failures related to information deficiencies regarding favorable production and contracts (Sinclair). Information theory suggests that free market outcomes may not be Pareto efficient under conditions of widespread information failures. It has been shown that even when the government faces the same informational constraints as private agents, there generally exists a set of Pareto-improving government interventions (Greenwald and Stiglitz, Stiglitz). Bartik also discusses how imperfect information related to human capital and research knowledge may rationalize regional economic development policies.

Recent regional economics literature has demonstrated that information gaps about market opportunities may be especially lacking for struggling rural and urban areas (Weiler; Weiler, Scorsone, and Pullman). In reviewing the literature on import liberalization policies, Lall and Latsch conclude that empirically oriented micro-level processes and behavioral mechanisms are the most promising for guiding policy decisions regarding imperfect information. Individual tourist visits might fill the gap in market information and help explain trade.

Kulendran and Wilson tested three hypotheses that (a) business travel leads to international trade, (b) international trade leads to international travel, and (c) international travel, other than business, leads to international trade. They found support for their hypotheses using cointegration and Granger-causality techniques in analyzing aggregate international trade and travel flow data for Australia and its four main trading partners of the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Japan. They discovered that real exports from Australia Granger-cause holiday travel to the United States and United Kingdom. Support was also found for the hypothesis that international travel, other than business travel, leads to international trade. However, limited evidence was found that imports influence international travel. Also using aggregate time series data, Shan and Wilson found two-way Granger causality between international travel and trade for China with Australia, Japan, and the United States. Their results imply that trade flows are linked with tourism for China and that tourism forecasting studies should simultaneously consider trade and tourism effects.

Prior studies have also found a link between export activity and firm characteristics such as size, experience, years in business, and type of product. For example, Cavusgil and Naor found that larger firms are more likely to develop exports because they are better able to reallocate resources and expand into foreign markets. In a survey of Wisconsin firms, Moini found that 38.7% of firms with more than 50 employees were exporters while only 10.4% of nonexporting firms had over 50 employees. Larger firms are also more likely to already have multiple site locations and distribution logistics in place. These characteristics allow them to enter international markets with greater ease than firms without these traits. Adequate cross-cultural skills needed for exporting have also been found to be positively associated with larger firms (Ali and Swiercz). Years in business, most likely related to experience, is another firm characteristic that has been shown to be influential for determining whether a firm trades or not. Moini found that 60.4% of exporters had been in business for more than twenty years versus a somewhat reduced 52.6% of nonexporting firms.

Jensen and Hollis estimated a single equation model of export status where firms were classified as either nonexporter/nonintender, export intender, low level of export involvement, or highly involved with exports. They hypothesized that a number of firm characteristics such as type of product sold, number of employees, years in business, sole proprietorship ownership, wholesale distribution, and regional location would influence the export status of the firm. However, many of their hypothesized variables were not found to be statistically significant. A significant negative effect was found for bakery products, one of seven product types considered, and for sole proprietorship ownership. Only the two highest sales categories and the western region were found to have a positive and statistically significant impact on exports. Although regional location has obvious advantages related to travel logistics and production opportunities, location may also influence a manager's perspective toward trade. Shoham and Albaum report that the strongest predictor of a manager's perception regarding export barriers is “cultural distance” or a difference in management's attitude toward exporting by region. They support their main conclusion with standard descriptive statistics and multiple regression results of a survey of Danish firms. The above-mentioned studies indicate that firms are not homogeneous in their ability to capitalize on trade opportunities. Thus, quantifying factors that influence a firm's propensity to trade are important for targeting firms and prioritizing policies and activities that will expand trade the most.

This study analyzes how both firm characteristics and cross-border tourism travel impact a firm's propensity to trade. A key contribution of this article is implementing a simultaneous equations model to analyze the joint impacts of trade and tourism using cross-sectional data. The following section discusses our survey data and the ordered probit—probit model we utilize to quantify our hypothesized relationships. Then, results of our bivariate model are presented and followed by a conclusion section that discusses the policy implications of this study.

Data and Methods

To quantify the impact of tourist and venture visits and firm attributes on cross-border trade, we analyzed survey data obtained from Arizona agribusiness firms regarding their business activities in Sonora.1 With the help of the Arizona Department of Agriculture and a technical advisory committee, 130 agribusiness leaders were identified. In selecting these businesses, we tried to maintain broad representation in terms of commodities, services, and geographical location. From these firms, we received 78 responses and 70 were useable for our analysis.2 At least two follow-up phone calls were made to individuals that did not return a completed questionnaire. Survey responses were received in 1997, three years after the initiation of NAFTA. Thus, survey participants could have had the opportunity to develop or at least explore cross-border trading opportunities after the euphoria of a much freer trading environment associated with NAFTA was put in place. In our survey, firms were asked to identify if they were doing any business or trade activities with Sonora3 and if they had ever investigated doing business with firms in Sonora. In addition, respondents were also asked whether they had ever visited Sonora as a tourist. From these questions, we constructed dependent variables for our model to quantify trade and tourism effects.

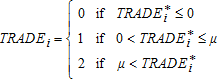

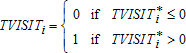

An Arizona firm's observed propensity to trade, TRADEi, has three possible discrete and ordered values. A value of 0 indicates that a firm has not ever traded or investigated any trading activities with Sonora, 1 indicates that they have not had any trade with Sonora but that they have investigated doing business with this cross-border state, and 2 indicates that the firm has traded with Sonora, either directly or through a broker. An Arizona agribusiness firm's observed propensity to visit Sonora as a tourist, TVISITi, is a 0 or 1 binary variable. Table 1 describes the variables and gives their respective sample means.

| Variable | Variable Definition | Sample Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| TRADEi | Represents the ith Arizona firm's inclination to trade with Sonora, Mexico: 2 = firm has traded with another firm in Sonora, directly or through a second handler, 1 = firm has considered trading with Sonora but has never actually traded, and 0 = firm has never investigated or considered trading with Sonora. | 1.443 |

| TVISITi | A binary variable: 1 = the owner has visited Sonora in the past as a tourist and 0 = the owner has not visited Sonora as a tourist. | 0.829 |

| Exogenous variables | ||

| FIRMSIZEi | Size of the ith firm's operation relative to others that sell similar products or services: 1 = below average, 2 = average, 3 = above average. | 2.143 |

| FIRMAGEi | How long the ith firm has been in business in Arizona: 0 = the firm has been in business for fifteen or more years, 1 = the firm has been in business for less than fifteen years. | 0.300 |

| GEODIVi | Importance of geographic diversity to the firm for having different regions of production with the same harvest/shipping period for reducing the firm's risk, measured on a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is not important and 5 is very important. | 3.614 |

| VVISITi | A binary variable: 1 = the owner has visited Sonora in the past to explore forming a joint business or trade venture, or has made a site visit to a similar operation, and 0 = the owner has never conducted any such kind of business venture visit in Sonora. | 0.543 |

| SPANISHi | Spanish speaking skills of respondent are: 1 = none, 2 = some, and 3 = fluent. | 1.829 |

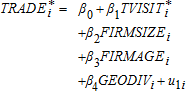

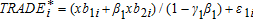

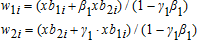

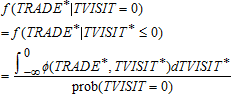

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

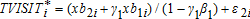

The structural model is simultaneous with unobservable endogenous variables on the right-hand side. An estimation procedure should account for this simultaneity and possible contemporaneous correlation between u1 and u2 to obtain consistent and efficient parameter estimates. Traditional instrumental methods are not feasible because of the unobservable nature of the endogenous variables. We derive the reduced form model from the structural model and estimate it with full information maximum likelihood methods.

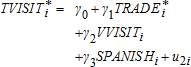

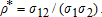

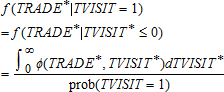

(3)

(3) (4)

(4)

(5)

(5) (6)

(6)

Empirical Results

Maximum likelihood estimates of parameters for the simultaneous two-equation model are provided in table 2. As hypothesized, regressors of TVISIT*, FIRMSIZE, and GEODIV positively impact TRADE*. Tourist visits to a foreign country are believed to heighten the awareness of potential business opportunities for entrepreneurs. Firms relatively larger than their competitors (FIRMSIZE) are more likely to already have multiple site locations plus the resources and expertise to manage sites from a distance, allowing them greater ease to enter international markets. The positive sign associated with GEODIV indicates that firms which benefit from geographical diversity, even when different regions have the same harvest and shipping date, are more likely to trade. The positive sign of FIRMAGE suggests that the openness or willingness to consider trade opportunities with Sonora by the younger firms (less than fifteen years of age) outweighs the effect of older firms being more established and able to expand abroad.5 Of the younger firms, 33.3% had considered trading in Sonora while only 20.4% of the older firms had considered trading. In addition, slightly more of the older firms were actually trading with Sonora than the younger firms, 61.2% versus 57.1%. Thus, only 5.5% of younger firms are not trading or have not considered trading compared to 22.5% of older firms. Moini's survey of Wisconsin firms did not differ greatly with respect to age either since he found 60.4% of exporting firms had been in business for more than 20 years versus 52.6% for non-exporting firms. TVISIT*, FIRMAGE, and GEODIV are statistically significant at the 10% level while FIRMSIZE is not.

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade equation | |||

| INTERCEPT | −2.594 | 0.893 | 0.004 |

| TVISIT* | 1.664 | 0.854 | 0.051 |

| FIRMSIZE | 0.220 | 0.294 | 0.455 |

| FIRMAGE | 1.165 | 0.677 | 0.085 |

| GEODIV | 0.467 | 0.272 | 0.087 |

| μ | 0.852 | 0.438 | 0.052 |

| Tourist visit equation | |||

| INTERCEPT | −0.009 | 0.492 | 0.986 |

| TRADE* | −0.759 | 0.355 | 0.033 |

| VVISIT | 1.565 | 0.421 | 0.000 |

| SPANISH | 0.394 | 0.284 | 0.165 |

| ρ | −0.158 | 0.590 | 0.789 |

| Log-likelihood | −74.841 | ||

| Sample size | 70 | ||

- Notes: μ is the threshold parameter associated with the ordered probit model and ρ is the contemporaneous correlation coefficient between the error terms of the trade and tourist visit equations.

VVISIT and SPANISH positively impact Arizona agribusiness proprietors' propensity to visit Sonora as tourists. TRADE* negatively impacts tourism visits to Sonora. This negative association is attributed to individuals not wanting to mix vacation with business travel if their business is already established in Sonora. But the exploration of new business or trade ventures and visiting operations similar to their own have a positive influence on tourism. Better exposure or familiarity with an area through venture visits appears to entice these same individuals to explore the region more as a tourist. In addition, individuals that are willing to accept foreign travel risks for tourism also appear willing to take these same travel risks for business. VVISIT and TRADE* are statistically significant at a 5% level in the tourist visit equation while foreign language abilities (SPANISH) is not, even though it has a positive sign.

A likelihood ratio test that coefficients on all explanatory variables in both equations are zero is rejected at a 1% level of significance. This is based on a calculated χ2 value of 46.20 with 8 df.6 Further evidence of model validation can be obtained from the prediction accuracy of the model. Overall, the model performs relatively well by predicting 37 of 70 sample points correctly. Given the six possible combinations of TRADE and TVISIT for each sample point, this 52.9% success rate appears quite reasonable (Greene, p. 834). Unlike a single equation case for a binary variable, where a naïve model has a 50% chance of making a correct prediction, a purely naïve model for the present two-equation system would have only a one-sixth chance (16.67%) of making a correct prediction.

Robustness of parameter estimates was evaluated using two separate procedures. First, the model was re-estimated by dropping observations one at a time with replacement. This “dropping procedure” is used to see how much an individual observation affects parameter estimates (Copas). Secondly, we use a “flipping procedure” recently proposed by Fay as a more powerful alternative to testing for the robustness of estimates obtained from a logistic regression. This procedure is a conceptually simple way to determine the potential of a single binary observation to affect the outcome of a probit regression. The procedure involves rerunning the regression once for each observation after changing the dependent variable response (from 0 to 1 or 1 to 0 for that observation only) and calculating changes in key statistics. We followed this method for the TVISIT variable and adapted the procedure for ordered TRADE responses by evaluating one-unit increment changes.

Following both these robustness procedures, parameter estimates were quite stable and within a relatively narrow range. The coefficient of variation for parameter estimates was generally less than 7% for dropping observations, less than 16% for flipping TVISIT, and less than 8% for flipping TRADE in one-unit increments. In addition, no qualitative changes were found for parameter estimates on TRADE, TVISIT, or firm characteristics that would change the interpretation of our analysis, suggesting that our data and model are quite robust.

Marginal Effects

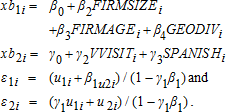

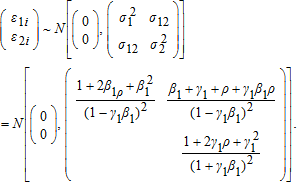

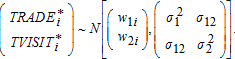

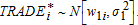

(7)

(7) (8)

(8) (9a)

(9a) (9b)

(9b)As described in table 1, all the explanatory variables in the model are themselves discrete and take a finite number of values. For such discrete explanatory variables, a differentiation technique (Greene, p. 877) may not be the most appropriate method to obtain marginal effects. This may especially be the case when comparing magnitudes with binary explanatory variables. Thus, we obtain the marginal effects of explanatory variables by comparing probabilities that result when the explanatory variable takes a different value, holding other variables at their sample means. For example, the marginal effect of a change in GEODIV on prob(TRADE = 2) is obtained by computing prob(TRADE = 2 | GEODIV = j + 1) − prob(TRADE = 2 | GEODIV = j), holding other explanatory variables at their sample means. All possible increments are averaged to obtain the marginal effect of GEODIV.7 Similarly, the marginal effect of a change in GEODIV on E[TRADE*] is computed as E[TRADE* | GEODIV = j + 1] − E[TRADE* | GEODIV = j], holding other explanatory variables at their respective sample means. We obtain the marginal effect of a binary dummy variable by comparing the probabilities that result when the binary dummy variable takes its two different values, holding other variables at their respective sample means. Marginal effects of all exogenous variables are computed using the distribution in (8). Marginal effects of a change in TVISIT on TRADE were obtained using the same discrete approach as for exogenous variables, but using the conditional distribution in (9) rather than (8). Standard errors associated with all marginal effects were calculated using the “delta method” (Gallant and Holly).

Table 3 provides the marginal effects and accompanying standard errors of all variables on TRADE. The impact of an individual's venture visit (VVISIT) to explore a joint business or trade opportunity or a site visit to a similar business in Sonora increases the probability of cross-border trade for this individual by 51.5% and the expected value of TRADE by 0.767. VVISIT has the largest and most statistically significant marginal impact of all exogenous variables. Marginal effects of exogenous variables are not equally comparable with the endogenous marginal effect of TVISIT, due to differences in a marginal distribution with no information on TVISIT versus a distribution conditional on TVISIT. However, the marginal effect of TVISIT is estimated to increase prob(TRADE = 2) by 30.2% at a 8.6% significance level.8 These results support the hypothesis that both formal business exploration and casual exposure to cross-border business opportunities have a positive impact on trade.

| Variable | Variable Range | Estimated Marginal Effects on | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| prob(TRADE = 0) | prob(TRADE = 1) | prob(TRADE = 2) | E[TRADE] | ||

| Effects based on marginal distribution for TRADE* | |||||

| FIRMSIZE | 1–3 | −0.019 | −0.027 | 0.046 | 0.065 |

| (0.030) | (0.042) | (0.071) | (0.100) | ||

| FIRMAGE | 0–1 | −0.083** | −0.147 | 0.230** | 0.313** |

| (0.046) | (0.100) | (0.124) | (0.159) | ||

| GEODIV | 1–5 | −0.049* | −0.048 | 0.098** | 0.147* |

| (0.034) | (0.031) | (0.058) | (0.090) | ||

| VVISIT | 0–1 | −0.252** | −0.264** | 0.515** | 0.767** |

| (0.075) | (0.114) | (0.121) | (0.165) | ||

| SPANISH | 1–3 | −0.052 | −0.081 | 0.132* | 0.183* |

| (0.043) | (0.057) | (0.093) | (0.133) | ||

| Effects based on conditional distribution for TRADE* | |||||

| TVISIT | 0–1 | −0.152 | −0.150* | 0.302* | 0.454 |

| (0.163) | (0.088) | (0.220) | (0.377) | ||

- Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses under estimated marginal effects. ** and * indicate statistical significance at a 5 and 10% level using a one-sided test for prob(TRADE = 0), prob(TRADE = 2), and E[TRADE], and a two-sided test for prob(TRADE = 1). Marginal effects of TVISIT are obtained using the conditional distribution for TRADE*. For example, −0.152 is obtained by evaluating prob(TRADE = 0|TVISIT = 1) − prob(TRADE = 0|TVISIT = 0), where the first probability is from the conditional distribution in equation (9b) and the second probability is from the conditional distribution in equation (9a). Marginal effects of all exogenous variables are calculated similarly, only using the marginal distribution for TRADE* given in equation (8). One-unit increases in non-binary variables were averaged to obtain their marginal effect.

Although our study supports earlier findings that large firms are more likely to trade than small firms, our results indicate that firm age has a greater influence on trade than the size of the firm. Firms that have been in business for less than fifteen years are 23.0% more likely to trade than older more established firms. The expected value of trade increases by 0.313 when a firm is less than fifteen years of age. This is more than half the impact of TVISIT on TRADE. The marginal effect of geographic diversity (GEODIV) on the expected value of trade appears relatively small at 0.147. But since GEODIV goes from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important), the total marginal impact from its minimum to maximum value is 0.472 or 61.5% of the impact of VVISIT on TRADE.

Results in table 3 are the effects of changing a single explanatory variable on trade, holding other variables constant. From a policy perspective, it is also useful to look at the joint impact of simultaneous changes in two or more variables on cross-border trade. Table 4 presents joint effects of changes in two or more selected variables. Due to nonlinearities in the model, the combined effect of two or more variables is not the sum of their individual effects. For example, in table 4, the joint effect of both a tourist and business venture visit increases the probability of trade by 0.687. This is 15.9% less than the sum of their individual marginal effects. Given that both TVISIT and VVISIT have relatively large individual impacts, it is not surprising that diminishing returns to trade are realized when these two variables are combined. The sum of individual marginal effects for a tourist visit and firm age differ by less than 4% from their combined marginal effect. The combined marginal effect of TVISIT and FIRMAGE on the probability that the firm will trade increases this probability by 0.570 versus 0.532 for the sum of their individual marginal effects. TVISIT, FIRMAGE, and VVISIT combined have a very large marginal effect of 0.836 on increasing the probability of the firm trading.

| Estimated Effects on | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | prob(TRADE = 0) | prob(TRADE = 1) | prob(TRADE = 2) | E[TRADE] |

| Effects based on conditional distribution for TRADE* | ||||

| TVISIT and FIRMSIZE | −0.193 | −0.167** | 0.360** | 0.553* |

| (0.168) | (0.079) | (0.195) | (0.356) | |

| TVISIT and FIRMAGE | −0.287 | −0.283** | 0.570** | 0.857** |

| (0.233) | (0.126) | (0.257) | (0.475) | |

| TVISIT and GEODIV | −0.287 | −0.119 | 0.406** | 0.692* |

| (0.237) | (0.078) | (0.198) | (0.430) | |

| TVISIT and VVISIT | −0.423** | −0.264** | 0.687** | 1.111** |

| (0.160) | (0.125) | (0.128) | (0.261) | |

| TVISIT and SPANISH | −0.205 | −0.205** | 0.410** | 0.615** |

| (0.162) | (0.091) | (0.193) | (0.344) | |

| TVISIT, FIRMAGE, and VVISIT | −0.543** | −0.293** | 0.836** | 1.378** |

| (0.190) | (0.133) | (0.122) | (0.290) | |

| Effects based on marginal distribution for TRADE* | ||||

| VVISIT and FIRMAGE | −0.333** | −0.335** | 0.669** | 1.002** |

| (0.088) | (0.121) | (0.129) | (0.185) | |

| VVISIT and SPANISH | −0.304** | −0.299** | 0.603** | 0.906** |

| (0.089) | (0.114) | (0.125) | (0.185) | |

- Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses under estimated marginal effects. **and * indicate statistical significance at a 5 and 10% level using a one-sided test for prob(TRADE = 0), prob(TRADE = 2), and E[TRADE], and a two-sided test for prob(TRADE = 1). Simultaneous one-unit increases were averaged where non-binary variables are considered to obtain marginal effects.

Conclusions

Estimated results from our survey data reinforce most of the findings of recent time series studies (i.e., Kulendran and Wilson; Shan and Wilson) regarding non-business international travel and trade. Using our cross-sectional data, we found strong support for the notion that Arizona agribusiness proprietors will be more likely to trade with their cross-border state of Sonora, Mexico, by up to 51.5%, if the individuals have made a business venture visit to Sonora. Tourist visits also increase the probability of trading for the firm, by as much as 30.2%, although statistically less significant than venture visits. Unlike Shan and Wilson, we found trade to have a negative impact on tourism travel for the firm. They found support for two-way causality between total trade and holiday travel for China with Australia, Japan, and the United States. Kulendran and Wilson also detected support for holiday travel to Granger-cause real total trade for Australia with the United States and Japan but not New Zealand or the United Kingdom. In addition, they did not find that trade influences holiday travel, although they found trade to Granger-cause total travel. Although results are mixed on trade influencing holiday travel, we attribute our negative association of trade on tourism with a desire of established proprietors to not mix vacation with business when traveling to a cross-border state. In addition, prominent business individuals may wish to minimize the exposure of kidnappings and ransom demands that have occurred in Mexico.

Our results strongly support the hypothesis that both formal and casual exposure of cross-border business opportunities impact trade positively. Business venture visits were found to have a greater influence on whether firms trade than traditional variables such as firm age and size. Tourist visits by themselves have a noticeably lower impact on swaying a firm to trade than when combined with firms that are also seeking geographic diversity, less than fifteen years of age or open and agile to trade opportunities, fluent in the foreign language, or relatively larger than their competitors. Trade missions sponsored by government entities can expose entrepreneurs to opportunities, but they probably will not change the exploratory nature and risk preferences of the individuals sponsored. Thus, the magnitude of our impacts for a tourist visit should not be equated with a sponsored trade tour, although we would still expect this to have a positive impact on trade.

Our findings suggest that making it easier for individuals to travel as a tourist can have a positive impact on trade, at least for border states. The “Sonora Only” program, adopted in the summer of 1995, does this by reducing the transactions cost of U.S. visitors going into Sonora beyond the Free Trade Zone. This program allows visitors to drive their vehicles into Sonora without posting a bond or providing an international credit card, and providing other documents. In addition, the program reduces the proof of citizenship requirement from a passport or birth certificate to a valid driver's license and waives the normal processing fee. Our results indicate that other border states in Mexico could improve their trade with the United States by adopting a similar policy for visitors to their states.

To our knowledge, this analysis is the first to endogenously model trade and tourism effects using cross-sectional data. Unlike aggregate time series studies, cross-sectional data provides insights into the kind of firms that should be targeted for trade. Our results indicate that communities seeking to develop or expand cross-border trading activities should first target entrepreneurs with an exploratory and venturesome spirit. Then, they should identify firms that are fairly young (less than fifteen years of age) and that desire to diversify their production risk through multiple geographic production regions. Firms whose managers possess foreign language fluency and are relatively larger than their competitors should be targeted to undertake exploratory visits. Results indicate that the joint effect of several variables exceeds 0.5. By targeting particular firms, the probability of trade can often be increased by as much as 50%.

While only cross-border trade and tourism are treated as endogenous variables in this study, other variables like venture visits, firm size, and language fluency are ultimately determined endogenously by the firm. Future firm-level analyses regarding the role that business and tourist visits can play in mitigating any market failures of imperfect information surrounding trade opportunities should consider treating more variables than just trade and tourism as endogenous. Business venture visits would be the first variable to consider given the large magnitude and statistical significance estimated for it here.