Prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions among an alopecia areata cohort from a US administrative claims database

Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA) is associated with an increased burden of autoimmune and inflammatory disease and mental health conditions that may have a negative impact on quality of life. However, the exact burden of comorbidities on US patients with AA and the clinical subtypes alopecia totalis (AT) and alopecia universalis (AU) compared with those without AA is not well understood. This retrospective cohort study aimed to assess the incidence rates and prevalence of AA and its clinical subtypes and examine the autoimmune and inflammatory disease and mental health condition diagnosis burden in US patients with AA and a matched cohort without AA. The Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database was used to select patients aged ≥12 years enrolled between October 1, 2016, and September 30, 2020, who had two or more AA diagnosis codes for the AA cohort. Three patients without AA were age-, sex-, and race-matched to each patient with AA. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions were evaluated at baseline and up to 2 years after the index date. In total, 8784 patients with AA (599 with AT/AU) and 26 352 matched patients without AA were included. The incidence rate of AA was 17.5 per 100 000 person-years (PY; AT/AU: 1.1 per 100 000 PY; non-AT/AU: 16.3 per 100 000 PY), and the prevalence was 54.9 per 100 000 persons (AT/AU: 3.8; non-AT/AU: 51.2). Patients with AA had a higher prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases than the matched non-AA cohort, including allergic rhinitis (24.0% vs 14.5%), asthma (12.8% vs 8.8%), atopic dermatitis (8.3% vs 1.8%), and psoriasis (5.0% vs. 1.6%). The proportions of anxiety (30.7% vs 21.6%) and major depressive disorder (17.5% vs 14.0%) were higher in patients with AA than those without AA. Patients with AT/AU generally had a greater prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory disease and mental health conditions than patients with non-AT/AU AA.

1 INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that has an underlying immunoinflammatory pathogenesis and is characterized by nonscarring hair loss of the scalp, face, and/or body.1 AA has an estimated prevalence of 6 to 7 million individuals in the United States alone, affecting patients of all races, ethnic groups, and sexes.2 The most common age for disease onset is 20 to 40 years,3, 4 but AA can also manifest in both children and adults older than 40 years, with an unpredictable clinical course of hair loss and regrowth.5 The clinical presentation of AA can be divided into several subtypes based on the extent of hair loss, including alopecia totalis (AT; characterized by complete loss of scalp hair) and alopecia universalis (AU; characterized by complete loss of scalp, face, and body hair).2, 6

AA has been associated with autoimmune diseases and other diseases and disorders (including asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, diabetes, hypertension, thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], and vitiligo) in studies in Taiwan,7 Korea,8 and Iran,9 and in a study of a regional health care system in the United States.10 AA also impacts quality of life, with many studies reporting that patients with AA experience an increased prevalence of mental health comorbidities such as depression and anxiety.10-12 However, large-scale studies on the autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions experienced by patients with AA representative of the entire US population have been limited, and comparisons with matched cohorts without AA have not been performed.

This study aimed to assess the incidence rates (IRs) and prevalence of AA and AA clinical subtypes in the United States, as well as examine the autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health condition burden in patients with AA compared with a matched cohort of patients without AA using a national administrative claims database.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

This retrospective, observational cohort study used the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart (CDM) database of administrative health claims for members of large commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans in the United States (excluding Medicare Fee for Service). All records were deidentified (in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act), and neither approval from an institutional review board nor informed consent from patients was needed or obtained.

2.2 Patient population

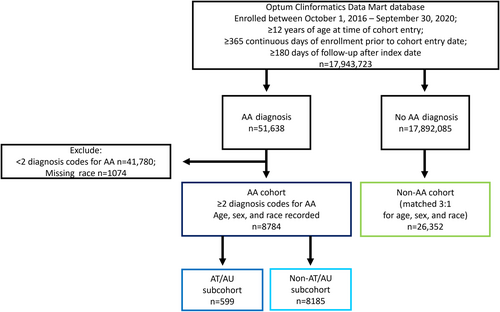

The study population consisted of patients with AA (AA cohort) and a matched cohort of patients without AA (non-AA cohort). To meet the inclusion criteria, patients were required to be enrolled in the CDM database from October 1, 2016, to September 20, 2020, and be ≥12 years of age at the date of cohort entry (defined as either the date when the 365 days of continuous enrollment was satisfied or October 1, 2016, whichever was later; the earliest possible cohort entry date was October 1, 2016), have ≥365 continuous days of enrollment prior to cohort entry and ≥180 days of follow-up after index date (date of first AA diagnosis for the AA cohort and date of cohort entry for the non-AA cohort), and have no missing data for date of birth or sex at cohort entry.

Patients in the AA cohort were identified as having two or more International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes for AA (L63.0-2; L63.8-9) with different visit dates separated by any duration apart. Patients with AA were further categorized as having AT/AU (ICD-10 codes L63.0/L63.1) or non-AT/AU AA (all other AA codes). Three patients without an AA diagnosis during the study period (non-AA cohort) were matched by age, sex, and race to one patient in the AA cohort. Any patients with AA with a diagnosis of alopecia of other cause (i.e., traction and scarring alopecia ICD-10 codes such as L65 for other nonscarring hair loss or L66 for cicatricial alopecia [scarring hair loss]) during the study period were excluded. A diagnosis of androgenic alopecia was permitted in either cohort. Patients in both cohorts were followed up from the index date until the end of the study period (September 30, 2020), death, dropout from the Optum CDM, or occurrence of end point of interest, whichever event occurred first.

2.3 Study variables

Demographic variables recorded at the index date were calendar year, sex, age, race, ethnicity, US geographic region, and insurance type. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health condition diagnoses were detected through medical claims. Autoimmune and inflammatory diagnoses included autoimmune thyroiditis (including Hashimoto disease or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis), atopic dermatitis, SLE, psoriasis, vitiligo, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, psoriatic arthritis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and multiple sclerosis. Mental health condition diagnoses included anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, mood disorders, personality disorders, and suicidal ideation or attempt.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics without hypothesis testing. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables. Data analysis was executed using statistical software SAS version 9.4 or later (SAS Institute Inc). Prevalence and IRs of AA were calculated as number of total cases divided by number of patients at risk during the study period and number of incident AA cases (defined as the absence of any diagnosis codes for AA at any point in the database prior to the index date) divided by person-years (PY) at risk, respectively, with 95% confidence interval. The prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions was determined from the first record of a given condition for the time period 1 year before and up to 2 years after the index date.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study population and demographics

Overall, 17 943 723 patients met the main inclusion criteria during the study period. A total of 8784 patients were included in the AA cohort, with 599 (6.8%) diagnosed with AT/AU (Figure 1). The non-AA cohort consisted of 26 352 matched patients. Patient baseline demographics were comparable across cohorts (Table 1). The mean age of the cohorts was 45.6 years and 55.6% were women; 59.2% were of White race, 20.3% were of Hispanic ethnicity, 10.2% were of Black race, and 10.2% were of Asian ethnicity. Patients from all geographic regions of the United States were included. Patients' insurance status included commercial insurance (80.9% and 79.1% for the AA and non-AA cohorts, respectively) and Medicare (19.2% and 20.9% for the AA and non-AA cohorts, respectively).

| Characteristic | AA cohort (n = 8784) | Non-AA cohort (n = 26 352) |

|---|---|---|

| AA subtype, n (%) | ||

| AT/AU | 599 (6.8%) | – |

| Non-AT/AU | 8185 (93.2%) | – |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 45.6 (17.9) | 45.6 (17.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 3904 (44.4) | 11 712 (44.4) |

| Female | 4880 (55.6) | 14 640 (55.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 900 (10.2) | 2700 (10.2) |

| Black | 894 (10.2) | 2682 (10.2) |

| Hispanic | 1787 (20.3) | 5361 (20.3) |

| White | 5203 (59.2) | 15 609 (59.2) |

| US region, n (%) | ||

| Midwest | 1635 (18.6) | 5994 (22.7) |

| Northeast | 1503 (17.1) | 2749 (10.4) |

| South | 3668 (41.8) | 10 830 (41.1) |

| West | 1947 (22.2) | 5913 (22.4) |

| Unknown | 31 (0.4) | 866 (3.3) |

| Insurance type, n (%) | ||

| Commercial | 7102 (80.9) | 20 836 (79.1) |

| Medicare advantage | 1685 (19.2) | 5497 (20.9) |

- Abbreviations: AA, alopecia areata; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis.

3.2 IRs and prevalence of AA

The IR of AA among a US population aged ≥12 years was 17.5 per 100 000 PY. IRs stratified by age categories were 16.0 per 100 000 PY for age 12 to 17 years, 17.5 per 100 000 PY for age ≥18 years, and 11.4 per 100 000 PY for age ≥51 years (Table 2). The IRs for AT/AU and non-AT/AU AA were 1.1 and 16.3 per 100 000 PY, respectively.

| Age categories | IR per 100 000 PY | Prevalence per 100 000 persons |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 17.5 | 54.9 |

| AT/AU | 1.1 | 3.8 |

| Non-AT/AU AA | 16.3 | 51.2 |

| 12–17 years | 16.0 | 40.8 |

| AT/AU | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Non-AT/AU AA | 15.5 | 38.2 |

| 18–50 years | 26.6 | 73.2 |

| AT/AU | 1.1 | 3.2 |

| Non-AT/AU AA | 25.5 | 70.0 |

| ≥51 years | 11.4 | 41.3 |

| AT/AU | 1.2 | 4.4 |

| Non-AT/AU AA | 10.1 | 36.6 |

| ≥18 years | 17.5 | 55.9 |

| AT/AU | 1.1 | 3.9 |

| Non-AT/AU AA | 16.4 | 52.0 |

- Abbreviations: AA, alopecia areata; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; PY, person-year.

The prevalence of AA during the study period of 2016 to 2020 was 54.9 per 100 000 persons, with a prevalence of 3.8 per 100 000 persons for patients with AT/AU and 51.2 per 100 000 persons for non-AT/AU AA patients. The prevalence of AA was 40.8 per 100 000 persons among those aged 12 to 17 years and 55.9 per 100 000 persons for those aged ≥18 years.

3.3 Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

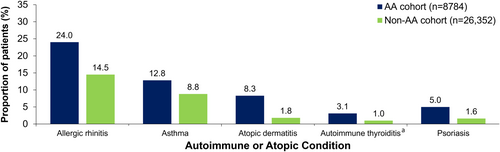

Patients with AA had a higher prevalence of all autoimmune and inflammatory diseases studied compared with the matched non-AA cohort during the study period (Table 3, Figure 2). Of all autoimmune and inflammatory diseases examined, the most common were allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis (24.0%, 12.8%, and 8.3%, respectively, compared with the matched non-AA patient cohort rates of 14.5%, 8.8%, and 1.8%, respectively).

| Autoimmune or inflammatory condition, n (%) | AA cohort | Non-AA cohort (N = 26 352) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall AA (n = 8784) | AT/AU subcohort (n = 599) | Non-AT/AU AA subcohort (n = 8185) | ||

| Allergic rhinitis | 2105 (24.0) | 179 (29.9) | 1926 (23.5) | 3808 (14.5) |

| Asthma | 1128 (12.8) | 83 (13.9) | 1045 (12.8) | 2330 (8.8) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 732 (8.3) | 58 (9.7) | 674 (8.2) | 467 (1.8) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditisa | 270 (3.1) | 44 (7.3) | 226 (2.8) | 253 (1.0) |

| Celiac disease | 75 (0.9) | 5 (0.8) | 70 (0.9) | 73 (0.3) |

| Crohn disease | 68 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 66 (0.8) | 113 (0.4) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 39 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 38 (0.5) | 103 (0.4) |

| Psoriasis | 437 (5.0) | 35 (5.8) | 402 (4.9) | 415 (1.6) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 59 (0.7) | 5 (0.8) | 54 (0.7) | 66 (0.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 73 (0.8) | 8 (1.3) | 65 (0.8) | 155 (0.6) |

| SLE | 149 (1.7) | 13 (2.2) | 136 (1.7) | 116 (0.4) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 132 (1.5) | 16 (2.7) | 116 (1.4) | 372 (1.4) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 123 (1.4) | 14 (2.3) | 109 (1.3) | 150 (0.6) |

| Vitiligo | 132 (1.5) | 8 (1.3) | 124 (1.5) | 42 (0.2) |

- Abbreviations: AA, alopecia areata; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- a Includes Hashimoto disease or chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis.

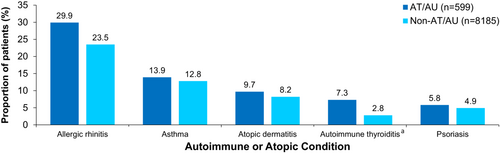

Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases were generally distributed similarly in patients with AT/AU and patients without AT/AU in the AA cohort (Table 3, Figure 3). Diseases with the largest proportional difference between patients with AT/AU and patients without AT/AU AA included allergic rhinitis (29.9% vs 23.5%, respectively) and autoimmune thyroiditis (7.3% vs 2.8%, respectively).

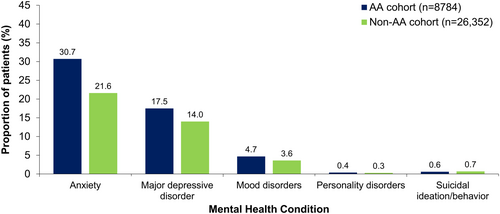

3.4 Mental health conditions

A greater proportion of patients with AA experienced anxiety, major depressive disorder, and mood disorders than matched patients without AA (Figure 4). The proportions of patients with personality disorders and suicidal ideation/behavior were lower and more similar between groups. Anxiety and major depressive disorder had the overall highest prevalence among patients with AA and those without AA (anxiety, 30.7% vs 21.6%; depression, 17.5% vs 14.0%, respectively).

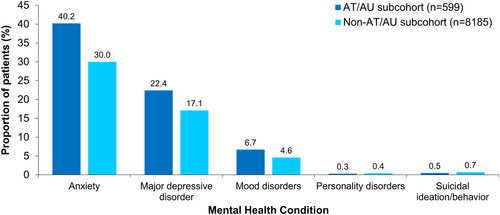

Anxiety was more common in patients with AT/AU than patients without AT/AU AA (40.2% vs 30.0%, respectively), as well as major depressive disorder (22.4% vs 17.1%, respectively) and mood disorders (6.7% vs 4.6%, respectively, Figure 5).

4 DISCUSSION

This retrospective descriptive US claims cohort study of patients with AA aged ≥12 years found that the prevalence and IR of AA (and its subtypes AT/AU) were 54.9 per 100 000 persons (3.8 per 100 000 persons) and 17.5 per 100 000 PY (1.1 per 100 000 PY), respectively. During the study period, the AA cohort had a higher prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions compared with a matched non-AA cohort. Specifically, a higher proportion of patients with AA had autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and autoimmune thyroiditis, and mental health conditions such as anxiety and mood disorders. Within the AA cohort, a higher proportion of patients with AT/AU than patients without AT/AU were diagnosed with most autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions that were analyzed, suggesting a gradient of risk with increasing AA severity.

The mechanisms for these findings may have multiple contributing factors. AA is a complex disease, with genetic and environmental factors contributing to disease onset and clinical course.1 However, the underlying pathophysiology of AA may conceivably also contribute to increased risk of other autoimmune, inflammatory, or mental health conditions. The pathophysiology of AA is mediated by dysregulation of cytotoxic T cells and cytokines released by the helper T cell (Th) type 1, Th2, and Th17 pathways.13-15 The same cytokines and autoreactive T cells are dysregulated in other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as atopy (which can lead to allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis),16 thyroiditis,17 vitiligo,18 type 1 diabetes,19 and psoriasis.20 In addition, exposure to increasing levels of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 17E and interleukin 22 has been found to correspond to worsening depression in patients with AA.21 One genome-wide association study of over 3000 patients with AA and 7500 controls from Central Europe and the United States found evidence that the correlation between major depressive disorder and AA is linked through a region of the genome corresponding to the major histocompatibility complex, which regulates many immunological functions.22 Another potential factor contributing to increased prevalence of mental health conditions among patients with AA may be coexisting autoimmune and atopic diseases that affect patients with AA. For example, psoriasis and atopic dermatitis are linked to increased prevalence of depression and anxiety as well as lower health-related quality of life,23, 24 which may, in turn, increase the rate of mental health conditions in patients with AA and coexisting psoriasis or atopic dermatitis.

On the other hand, the stigma associated with AA-related hair loss may also have a substantial negative impact on patient quality of life and mental health. For example, patients with AA frequently report ostracization, avoidance of social activities, and worsening performance at jobs or in school, which could contribute to the development of mental health conditions.25, 26 One UK-based study found that patients were more likely to subsequently develop depression and anxiety after diagnosis with AA,27 while another study of 2000 patients in Israel found greater odds of a diagnosis of depression following an AA diagnosis.28 This negative impact on mental health could impact other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Psychological stressors are associated with worsening symptoms of diseases such as asthma and atopic dermatitis.29-32 The relationship between AA and mental health conditions is complex and may be related to the underlying immunoinflammatory pathophysiology, increased risk from other autoimmune and atopic comorbidities, associated genetic risk components, and psychosocial effects. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationships between these factors.

Past regional US and international studies have found similar patterns of comorbidities among patients with AA. International studies have found significant associations of AA with atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, SLE, psoriasis, autoimmune thyroid disease, allergic rhinitis, and asthma.7-9 Within the United States, regional studies have found a high prevalence of thyroid disease, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, depression, anxiety, and hyperlipidemia in patients with AA compared with those without AA; however, none of these studies examined patients by clinical subtype.10 A meta-analysis of 87 studies of patients with AA (including one study that examined patients with AT/AU specifically) revealed an association between AA and inflammatory disease, SLE, thyroid diseases, and mental health conditions; additionally, patients with AA were at greater risk of developing all autoimmune diseases examined among 87 studies.33 In this study, rates of anxiety and depression were higher in patients in the AA cohort, similar to results seen in studies globally.7-10 A meta-analysis of 37 global studies found that the prevalence of depression and anxiety diagnoses was greater than that of the general population.34 Furthermore, the prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with AA was higher than the prevalence of depression and anxiety diagnoses, which indicated a risk of developing mental health conditions in these patients.34 The results of the present study therefore highlight for health care providers the importance of appropriate screening for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions upon AA diagnosis and periodically after, as this gives a higher chance for earlier intervention, which may lead to improved outcomes.

Prior studies of the US population in the 1970s showed an AA prevalence rate of 0.1% to 0.2%,35 while a recent systematic review of 93 global studies estimated the prevalence of AA in North America to be 2.47% and the prevalence of AT in North America to be 0.38%.36 This study is the first to our knowledge to examine the prevalence and IR of the AA subtypes AT and AU by age, and it was found that patients aged ≥51 years have a slightly higher prevalence and IR, followed by patients aged ≥18 years. Globally, the age-standardized IR of AA has been estimated to be 405.70 per 100 000 persons using data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.37 The difference between these results and the current study's findings of 54.9 per 100 000 persons may be due to regional variations in true IR, the rigorous requirement of two diagnosis codes for AA, and exclusion of patients with other alopecia diagnosis codes besides androgenic alopecia.

This study has some limitations related to the inherent design of a retrospective database analysis. First, the study was limited to patients with AA who had insurance through large commercial or Medicare Advantage health plans logged by the Optum CDM, and the underlying comorbidities of those covered under other types of insurance or those without coverage may not be reflected in this study. Patients with AT/AU were identified via diagnosis code only, and there was potential for misclassification by physicians who logged patient AT/AU as another form of AA. Patients with AA may also have a larger number of visits to health care providers than members of the matched cohort. This could potentially lead to more opportunities to be diagnosed with comorbidities, resulting in an overestimation of the difference in comorbidities between cohorts. Finally, this study used descriptive statistics. To adjust for potential confounding factors beyond age, race, and sex, further analyses will be required.

The strengths of this study include the examination of large cohorts, utilization of a strict cutoff of two or more AA diagnosis codes for cohort entry, and evaluation of the burden in patients diagnosed with specific AT/AU clinical subtypes.

In conclusion, in this real-world US claims–based retrospective cohort study, the IR of AA was 17.5 per 100 000 PY, and the prevalence was estimated at 54.9 per 100 000 persons; higher proportions of patients with AA were diagnosed with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions compared with those without AA. Patients with AT/AU generally experienced a higher prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and mental health conditions compared with patients without AA and without AT/AU AA. Awareness of these associations could help physicians better assist patients with AA through appropriate comorbidity screenings and treatment management, potentially prior to progression to more extensive clinical subtypes of AA or the development of mental health conditions related to AA diagnosis. Future research is needed to examine these associations and potential causal relationships between AA and these comorbidities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Pfizer. Medical writing support for the development of this publication was provided by Carolyn Maskin, PhD, of Health Interactions, Inc, and was funded by Pfizer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

At the time of the study, PG and CW were employees of Pfizer Inc. and may hold stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc. All other authors are employees of and may hold stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used and analyzed in the current study are available from OptumLabs through the OptumLabs Data Warehouse. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and therefore are not publicly available. However, the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from OptumLabs.