Psoriatic arthritis and its special features predispose not only for osteoporosis but also for fractures and falls

Abstract

Limited data are available on the predisposing factors to fractures and falls of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Our study intended to explore the differences between PsA patients and controls, concerning bone mineral density (BMD), the 10-year fracture risk, the number of prevalent fractures, the frequency of falls and to investigate the association of the same factors with PsA disease characteristics within the PsA group. Medical reports of 61 PsA patients and 69 consecutive, age-matched controls were analyzed, physical examination and bone mineral density (BMD, and T-score) were performed, and the 10-year fracture risk was calculated. The results were subjected to statistical analysis. Femoral neck BMD, as well as vertebral and femoral neck T-scores were lower, the odds ratio (OR) for low BMD and the 10-year risk of hip fracture was higher (p = 0.0029; 0.0002, p < 0.0001, OR = 21,9, p = 0.014) in the PsA group. The PsA patients were more predisposed to prevalent fractures, including peripheral fractures, and vertebral fractures as well as falls (OR 3.42; 2.26; 13.33; 3.95, respectively), compared to controls. Within the PsA group (beyond the age) scalp psoriasis and late-onset psoriasis, were significantly associated with a greater number of prevalent fractures (p = 0.0049; 0.029), while the number of falls per year correlated with late-onset psoriasis and the flexural psoriasis (p = 0.007; 0.023). Our results suggest that PsA is an independent risk factor for reduced bone density and falls hence to related bone fractures. Patients with late-onset psoriasis are more likely to suffer falls and related fractures, especially if their disease is characterized by the involvement of the hairy scalp and body folds.

1 INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is the most common comorbidity in psoriasis, which can be observed in up to 30% of psoriatic patients with a population-level prevalence of around 0.1%.1, 2 Osteoporosis, which belongs to the most prevalent diseases in the developed world, afflict every other woman and every fifth man in the population over 50 years of age.2 More patients are hospitalized with fractures resulting from osteoporosis (OP) than with myocardial infarction and stroke together.3 Certain inflammatory rheumatic disorders are known risk factors for OP, of which the best known is rheumatoid arthritis (RA).4 According to recent data, spondylarthritides are also associated with increased bone loss,5 however controversial data have been published on the incidence of OP in PsA, which also belongs to the group of spondylarthritides,6-12 just as regarding the relationship between bone loss and PsA. Moreover, no reliable data are available on the association of bone mineral density (BMD) with the type of the psoriatic disease, the characteristic cutaneous, nail symptoms, and articular involvement. Importantly, there are also no data on the association between fractures and falls and PsA characteristics, although according to current data, low-energy fractures are more common in PsA patients than in the age-matched general population.7

This study was intended to evaluate the difference between patients followed-up for PsA and age-matched controls not suffering from any disorder predisposing to osteoporosis, with regard to BMD, 10-year fracture risk calculated with FRAX, the number of low-impact prevalent fractures, and the frequency of falls. Furthermore, correlations were assessed among the same factors with the characteristics of the PsA (activity, the extent and type of cutaneous symptoms, disease duration and type, medication) – with particular attention to specific manifestations (enthesitis, dactylitis) and disease forms predisposing to PsA (psoriatic involvement of body folds, scalp, and nail).8

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with PsA fulfilling the CASPAR classification criteria,9 and age-matched controls who consented to use their data for scientific purpose, were enrolled into the study.

Patients with other inflammatory arthritis (other spondylarthritides, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic autoimmune disorders), other diseases with a possible influence on bone metabolism (such as primary hyperparathyroidism, thyroid disease, renal failure, malabsorption, malignancy, and excessive alcohol consumption) were excluded. The same was applied to patients who received longer than 3-month drug therapy acting on bone metabolism (including corticosteroids in a dose higher than 5 mg, thyroid hormone, estrogens/androgens).

The control group included randomly assigned age-matched patients referred by their attending physician to our institute for osteoporosis screening using Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA), and who did not fulfill the exclusion criteria listed above.

2.2 Study population, type of the study

An observational cohort study was performed involving 61 patients under the care of the Division of Rheumatology, “Kenézy Gyula” Campus, Clinical Center and at the Division of Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine University of Debrecen, as well as 69 controls randomly selected according to the above criteria.

2.3 Implementation of the study

Patients and controls were recruited and included into the study between September 2021 and March 2022. A signed informed consent was obtained from eligible patients, followed by reviewing their medical records to collect, clinical baseline data, regularly administered medicines, the consumption of alcohol, tobacco smoking, factors predisposing for falls (visual disturbance, impaired balance, dementia), prevalent fractures, and the number of falls suffered over a year which were recorded in both (PsA and control) groups using an interrogation method. The prevalent fractures were confirmed by medical documentation in all cases. Subsequently a physical examination was performed, and PsA disease-specific properties (the onset, duration, and type [early- or late-onset] and extent of psoriasis [BSA], the type of cutaneous symptoms [plaque or guttate], involvement of the scalp, body folds, or the nails, the distribution of PsA [peripheral or axial], the presence of enthesitis or dactylitis, and medicines administered for the treatment of the disease) were recorded. Based on the recommendation of Henseler and Christophers, early onset psoriasis was diagnosed if the psoriatic symptoms began before the age of 40 years while late-onset psoriasis was diagnosed when skin symptoms began at the age of 40 or older.10 The armpits, the navel, the areas under the breasts (in case of women), the inguinal and perineal areas, and the area between the buttocks were considered as body folds. Disease activity was evaluated with the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) in axial, and using the 3-variable Disease Activity Score (DAS28) in peripheral involvement.11 BMD was measured in the lumbar spine in vertebrae L1 through L4, as well as in the left femoral neck using a Lunar Prodigy densitometer (GE Healthcare Holding LLC) according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. In patients with a previous hip fracture or severe joint deformity/destruction, densitometry was performed on the right femoral neck. The 10-year fracture risk was calculated using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX, University of Sheffield).12

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University of Debrecen.

2.4 Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows software package (version 27.0, SPSS) was used. After the test of normality (Shapiro-Wilks), the values of scale variables in the two groups were compared using either Student's t-test, or non-parametric Mann–Whitney test. We applied Fisher's exact test and chi-square test to investigate the association between nominal variables, and Kendall's tau for ordinal variables. The significant predictors of binary outcome variables (disease; presence of osteopenia or osteoporosis) were identified with forward stepwise logistic regression, and those associated with the number of bone fractures or falls using ordinal regression.

3 RESULTS

3.1 BMD, fracture risk, the number of prevalent fractures and frequency of falls in the PsA and in the control group

3.1.1 Distribution of basic clinical data in the two groups

Before we started examining the main endpoints, we compared the two groups in terms of key factors important for bone loss and fracture. The two groups did not differ significantly regarding age (two-sample t-test: p > 0.1), BMI (Mann–Whitney test: p > 0.1) and factors predisposing to falls (visual disturbance, impaired balance) (Fisher's exact test: p > 0.1). However, the proportion of males was significantly greater in the PsA group (25/61) than among the controls (7/69) (Fisher's exact test: p < 0.0001). The close-to-equal male–female ratio in the PsA group corresponded to the usual in PsA, while the female dominance observed in the controls represented the average population referred for OP screening. When limiting our comparison between the PsA and control group to the female patients, we found almost the same significant differences as for the whole groups. Compared with the controls, regular, although not excessive alcohol consumption (regular intake of 1 to 2 units at the most) and corticosteroid therapy (ever), or the consistent administration of proton pump inhibitors were more common in the PsA group (Fisher's test: p = 0.046, p = 0.0004, and p = 0.0006, respectively). The differences mentioned above were subsequently not found to be independent influencing factors for the variables examined in the objectives according to statistical analysis (forward stepwise logistic regression and ordinal regression: p > 0.1). The detailed patient data are shown in the Tables 1 and 2, Tables S1–S4.

| Parameters | PsA patients (n = 61) | Controls (n = 69) | Fisher's p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 25 (41%) | 7 (10%) | <0.0001 | |

| By query | Smoking | 21 (34%) | 14 (20%) | 0.078 |

| Alcohol consumption | 4 (7%) | 0 | 0.046 | |

| Visual disturbance | 4 (7%) | 7 (10%) | >0.1 | |

| Impaired balance | 10 (16%) | 7 (10%) | >0.1 | |

| Number of falls | 34 (56%) | 7 (10%) | 0.0018 | |

| From medical records | Dementia | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Steroid therapy (ever) | 16 (26%) | 3 (4%) | 0.0004 | |

| Prolonged PPI therapy | 33 (54%) | 17 (25%) | 0.0006 | |

| Number of prevalent peripheral fractures | 38 | 17 | 0.024 | |

| Number of prevalent vertebral fractures | 16 | 4 | 0.0029 | |

| Peripheral fractures occurred | 21 (34%) | 13 (19%) | 0.048 | |

| Vertebral fractures occurred | 10 (16%) | 1 (1%) | 0.003 |

- Abbreviations: PPI, proton pump inhibitor; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

| Parameters | PsA patients (n = 61) | Controls (n = 69) | Mann–Whitney | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Quartiles | Median | Quartiles | p | ||||

| Age (years) | 63.0 | 57.0 | 69.5 | 66.0 | 58.0 | 72.0 | >0.1 | |

| BMI | 28.6 | 25.5 | 31.6 | 30 | 25.5 | 33.4 | >0.1 | |

| DEXA results | L1-4 BMD | 1.08 | 0.97 | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.21 | >0.1 |

| Femoral neck BMD | 0.91 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.0029 | |

| L1-4 T-score | −0.50 | −1.30 | 0.55 | 0.40 | −0.25 | 1.15 | 0.0002 | |

| Femoral neck T-score | −1.10 | −1.65 | −0.20 | −0.10 | −0.60 | 0.60 | <0.0001 | |

| FRAX calculator | FRAX (for major fractures) | 4.9% | 3.3% | 9.6% | 4.6% | 3.6% | 5.8% | >0.1 |

| FRAX (for hip fractures) | 1.25% | 0.5% | 3.5% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 1.2% | 0.014 | |

- Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; DEXA, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; FRAX, fracture risk assessment tool; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

3.1.2 BMD, fracture risk, the number of prevalent fractures and frequency of falls in the PsA and in the control group

The BMD values measured in the lumbar spine were not significantly different between the two groups (Mann–Whitney, p > 0.1). However, BMD values measured in the femoral neck, as well as the T-scores of the spine and of the femoral neck were significantly lower in the PsA than in the control group (Mann–Whitney, p = 0.0029, p = 0.0002, and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Table 1). Considering the whole (PsA and control) study population, the presence of reduced bone density correlated with the presence of PsA and inversely correlated with BMI (logistic regression, p < 0.0001, and p = 0.0026, respectively). In the PsA group, lower (in the osteopenic or osteoporotic range) vertebral and femoral neck BMD was significantly more common than in controls (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.001). The odds ratio (OR) of a PsA versus control patient for having osteopenia or osteoporosis in general was 21.9 (CI 7.1–67.7); specifically, 37.0 (CI 8.3–164.6) for the femoral neck and 12.9 (CI 2.8–58.8) for the spine.

The FRAX tool for the estimation of fracture risk did not reveal a meaningful difference between the two groups concerning the risk of major osteoporotic fractures (Mann–Whitney, p > 0.1). In contrast the ten-year risk of hip fractures was significantly higher in the PsA group (Mann–Whitney, p = 0.014), as shown in Table 1.

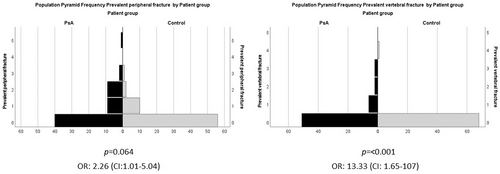

Regarding the number of prevalent fractures, the occurrence (several fractures/1 fracture/no fracture) of prevalent fractures was significantly higher in the PsA group than in the control group (16/10/29 vs. 3/10/56, significance of Kendall's tau, p < 0.001). Otherwise, the fracture prevalence of the control group did not differ from that of the average population of a similar age.13 The number of prevalent peripheral fractures (38 vs. 17) and the vertebral fractures (16 vs. 4) was significantly higher in PsA groups than in controls (Mann–Whitney test for the distribution of fracture numbers, p = 0.024, p = 0.0029) (Table 1). In PsA patients versus controls, the OR of having a prevalent fracture was 3.42 (CI: 1.56–7.52, p = 0.002) in general, it was 2.26 (CI: 1.01–5.04, p = 0.048) for peripheral fractures, and 13.33 (CI: 1.65–107, p = 0.003) for vertebral fractures. The distribution of prevalent peripheral and vertebral fractures is illustrated by the frequency histogram in Figure 1.

In the PsA group the number of falls was significantly greater than in the control group (34 vs. 7, significance of Kendall's tau test for the distribution of fall numbers: p < 0.001) and PsA patients versus controls OR for suffering of falls was 3.95 (CI: 1.17–13.27, significance of Fisher's exact test, p = 0.0018) (Table 1).

3.2 Factors related to BMD, fracture risk, number of prevalent fractures and frequency of falls within the PsA group

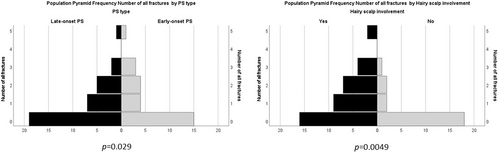

No significant correlation was found between BMD, fracture risk and PsA disease-specific characteristics (ordinal regression analysis and forward stepwise logistic regression p > 0.05). Ordinal regression analysis showed that (beyond the age) a higher number of prevalent fractures were significantly associated with the involvement of the scalp (p = 0.0049; see the frequency histogram in Figure 2), and the late onset of psoriasis (p = 0.029).

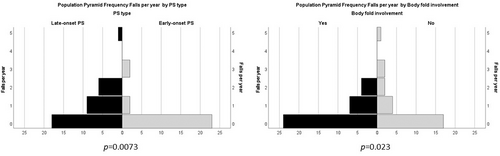

In the PsA group the number of falls was significantly associated with the late onset of psoriasis (ordinal regression analysis, p = 0.0073), and with the psoriatic involvement of body folds (p = 0.023; see Figure 3).

4 DISCUSSION

The relationship between psoriasis and bone loss has been investigated by several authors, delivering often controversial results. The findings of the large-scale HUNT3 study suggested that patients with cutaneous symptoms only, have no higher risk neither for increased bone loss, nor for fractures compared with the non-psoriatic population.14 On the other hand, Attia et al showed that reduced bone density is more common in patients with PsA, than in those with psoriatic skin symptoms only.15 A meta-analysis published in 2016 processing data from 21 studies, found 13 that supported an increased bone loss in PsA patients.16 Analyzing social insurance data of 183 725 psoriatic patients including 28 765 with PsA, Kathuria et al found that both psoriasis and PsA predispose to osteopenia, osteoporosis, and low-impact fractures (OR 2.86–2.97, and 2.35).17 In their recently published meta-analysis, Chen et al concluded that by itself, neither psoriasis nor PsA is associated with an enhanced risk for osteoporosis. However, they found a significantly greater incidence of low-impact fractures in patients, which underlines that BMD is only one of the factors influencing fracture risk.18 Our results are consistent with those of Kathuria et al. and suggest that osteopenia or osteoporosis are significantly more common in PsA patients both in the spine and in the femoral neck (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.001) (OR 12.9 and OR 37).

Moreover, according to our results the FRAX tool used to estimate fracture risk did not reveal any differences (p > 0.1) in the 10-year risk for major osteoporotic fractures; however, the risk of hip fractures was significantly higher (p = 0.0005) in the PsA group than in controls.

In the literature, there is a paucity of data on the correlation between the specific characteristics of PsA and bone fractures. According to a meta-analysis published recently, PsA patients have a vastly increased chance of suffering a vertebral fracture (OR 2.09).19 In accordance with this, we also found a significantly greater chance of sustaining peripheral and vertebral fractures by our PsA patients (OR 2.26, and OR 13.33).

Our study confirmed also the results of Paskins and coworkers who found a 10% higher fracture risk in patients with late-onset psoriasis compared with age- and sex-matched controls.20 Both late-onset psoriasis and scalp involvement increased the fracture risk also in our cohort (p = 0.029 and p = 0.0049).

The relationship between PsA and the number of falls sustained over a year was investigated by just a single group of researchers. Their recently published paper describes that in PsA patients, the arthritic involvement of the foot is associated with an enhanced risk for falls.21 We also showed a significantly greater number of falls in patients with late-onset psoriasis and with the flexural psoriasis (p = 0.0073 and p = 0.023).

Our one of the most interesting findings that the psoriatic involvement of the scalp and body folds enhanced the risk of fractures and falls is similarly as challenging to answer as why a number of features, such as scalp lesions, nail dystrophy, and flexural lesions (of these scalp laesions most significantly) increase the risk of PsA in patients with psoriasis.8 Some authors have shown, that severe arthritis in the fingers and extremities can be observed in patients with scalp psoriasis22 but there are no similar observations in patients with flexural psoriasis. In search for possible underlying mechanisms, Stanmore and al. showed an increased tendency for falls in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and by analogy of this it is reasonable to assume that PsA may as well increase fatigue and decrease the movement functions, muscle mass, mobility, and stability of gait – and these could aggregately cause impairment of the mechanisms that prevent falls.23 There are also sporadic data showing that enthesitides of the lower extremity can alter the mobility of the foot and the pattern of gait.24

5 CONCLUSIONS

According to our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between the specific properties of PsA and bone fractures or falls. Based on our results, PsA essentially predisposes to reduced bone density, falls, and related fractures. Therefore, checking BMD regularly and starting primary prevention should be seriously considered in PsA patients. The emergence of osteoporosis should be expected primarily in PsA patients and in those with a smaller body weight. Patients with late-onset psoriasis face an especially high risk of falls and low-energy fractures – particularly, if there is or ever was psoriatic involvement of the scalp and body folds. Accordingly, the prevention of falls and fractures requires particular attention. This underlines the importance of the cooperation between the dermatologist and the rheumatologist, aimed at the complex and successful management of PsA patients.

6 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

One of the limitations of our study is the small sample size and the single center nature of the study. Moreover, the proportion of men in the PsA group was higher than in controls, but the gender itself did not prove to be an influencing factor in terms of any of the variables examined in the statistical analysis. The gender distribution in PsA patients is equal as opposed to the female dominance observed in those referred for osteoporosis screening, so it is difficult to set up age and sex-matched control groups. However, we feel that the results of our study are valid and draw attention to important new correlations regarding the relationship between PsA and osteoporosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Andrea Halasi, Andrea Szegedi, Dániel Törőcsik, József Varga, Nikolett Farmasi, Gabriella Szűcs, Tünde Tarr and János Gaál declare that they have not accepted funds, consultancy, speaking, education or commissioned fee, fellowship, research or education grant, conference registration fee, travel or accommodation expenses from any company in connection with this study. Furthermore they do not have any stock and shares in any entity that could be influenced in any way by the results or conclusion of this study. They had full access to all data in this study and are prepared to take full responsibility for its accuracy.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University of Debrecen. and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All authors have confirmed that the content can be published and agreed to submit it for consideration for publication in the journal.