Outcomes and Safety of Blenderized Tube Feedings in Pediatric Patients

A Single Center's Experience

This article has been developed as a Journal CME and MOC Part II Activity by NASPGHAN. Visit https://learnonline.naspghan.org/ to view instructions, documentation, and the complete necessary steps to receive CME and MOC credits for reading this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jpgn.org).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Recently, significant interest from families and healthcare providers has arisen to use blenderized tube feedings (BTF). Although many institutions are providing this nutritional option, literature documenting outcomes and safety is lacking.

Methods:

A retrospective chart review was performed on pediatric patients receiving BTF at Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital between January 2013 and April 2017. Demographic data and dietary information before and after BTF were collected. Reasons for diet initiation, symptoms, and anthropometrics were recorded. Adverse events and outcomes were assessed through physician documentation and relevant medication changes.

Results:

Thirty-five patients (24 boys) received BTF. Age at initiation of BTF ranged from 1 to 19 years (mean 8.3 +/− 5.8 [SD] years). Length of follow-up ranged from 1 to 45 months (mean 15 +/− 12.2 months). The most common reason for starting BTF was gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (N = 32). Almost all patients were on medications for GERD, constipation, or gastrointestinal dysmotility before starting BTF (N = 33). Majority of patients had improvement in relevant symptoms (N = 20); 13 of 33 patients on gastrointestinal medications were able to wean or stop medication(s). BMI z scores did not differ before and after BTF initiation (P = 0.558). No serious life-threatening adverse events were found.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that BTF is a safe dietary intervention that may improve gastrointestinal symptoms in pediatric patients. Further prospective studies are needed to compare safety and efficacy of BTF and commercial formulas in pediatric patients.

What Is Known

- Blenderized tube feedings are table foods that are pureed and administered by gastrostomy tube.

- Two pediatric studies have shown gastrointestinal symptom improvement with blenderized tube feedings.

What Is New

- Our cohort showed improvement in constipation as evidenced by medication changes and physician documentation, which is discrepant from results of another recently published pediatric study.

- Contrary to another recently published pediatric study, our cohort did not show significantly higher calorie needs in children receiving blenderized tube feedings.

Recently, increasing interest to use blenderized tube feedings (BTF) has been expressed by families and healthcare providers. BTF are table foods that are pureed by blender and given via gastrostomy tube (G-tube). Although many centers are providing this nutritional option, there is a paucity of literature regarding blenderized diet recipes, safety, and outcomes.

In 2011, Cincinnati Children's Hospital conducted a trial with 33 children post-fundoplication surgery with gagging and retching. BTF were designed to meet each child's nutritional goals. They concluded that in children post-fundoplication surgery, BTF may decrease gagging and retching behaviors (1.).

Recently a prospective study of 20 children using BTF was performed at Sick Children's Hospital in Toronto. Prevalence of vomiting and use of acid-suppressive agents was significantly decreased with BTF. This study also, however, reported that children required 50% more calories to maintain their BMI while on BTF compared with commercial formula (2.).

Our study evaluates a cohort of medically complex pediatric patients on BTF in a single center. We evaluate reasons patients were initiated on BTF and outcomes, such as anthropometric data and adverse events.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients followed by the pediatric gastroenterology group at Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJUH) who received BTF from January 2013 to April 2017. A list of patients followed by our pediatric gastroenterology group previously compiled by the dietitians for clinical purposes was used to identify patients receiving BTF. The study was approved by the Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Patients

Inclusion criteria was any pediatric patient <22 years of age at initiation of BTF that received BTF for any length of time during the study period. Selection of charts reviewed was independent of underlying diagnosis, type, or schedule of previous or current formula/oral feeding or medication history. Children were not excluded if they received oral feedings in addition to G-tube feedings. Protocol at our institution is for ≥14 French tube G-tube size for BFT, if needed dilation was performed. Demographic data including gender, feeding tube size and type, age at initiation of BTF, and reasons for initiation of BTF were collected. Duration of follow-up was calculated using the start date of BTF to either the end of the study period or stop date of BTF if during the study period.

Anthropometric Data

Weight and height percentiles were collected, and BMI percentiles for children ≥2 years of age or weight/length percentiles for children <2 years of age were calculated before and after initiation of BTF. CDC growth charts were used for children ≥2 years old, and WHO growth charts were used for children <2 years old. Standard definitions of weight categories for BMI were used: normal BMI 5% to 85%, underweight <5%, and overweight >85%. Z-scores were calculated for BMI or weight for length depending on patient age before and after initiation of BTF. Statistical analysis was performed using a paired t-test.

Dietary Data

Dietary information before starting BTF was collected including brand of formula, concentration, method of administration (bolus and/or continuous), rate, and additives. Formula information was analyzed in groups based on formula type-whole protein cow's milk, soy, hydrolyzed, elemental and other. Presence or absence of oral intake was documented.

As part of our clinical protocol, before starting BTF, detailed information regarding prior food exposure if any, food intolerances or allergies and food preferences (personal, religious, cultural, etc) were discussed. Recipes were then designed by the dietitian based on the above discussion as well as calorie goals, which were extrapolated from the prior formula regimen and estimated nutrient requirements using dietary reference intakes for age. Dietitian-provided recipes included amounts to be given from each food group (eg, cups of vegetable) but did provide caregivers with some flexibility and ability to vary the diet within these food groups (Appendix A1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/B924 and A2: Sample BTF recipes, http://links.lww.com/MPG/B925).

Our clinical protocol included a transition period from commercial formula to BTF with pureed baby food and then to BTF with table foods. This transition involved a standardized algorithm of up to 8 steps. The length of time between transition from commercial formula to BTF with table foods was somewhat individualized, but overall patients were expected to spend about 1 week at each step to ensure tolerance (Appendix B: Institutional algorithm regarding transition process, http://links.lww.com/MPG/B927). Of note, commercial formula was often included in BTF recipes and the decision to remove formula from the BTF recipe was made through discussions between the physician, dietitian, and caregiver.

The decision to include the baby food step as part of our clinical protocol was through discussions between the pediatric gastroenterologists and dietitians. It was felt the baby food step would allow for ease of transition for caregivers from formula to homemade BTF and allow for improved tolerance for patients during this transition. Participants were instructed to use blenders with settings capable of producing cake batter consistency feedings.

Caregivers were also provided brief education regarding safe food preparation by the dietitians to minimize risk of foodborne illness.

Information on dietary components of BTF was collected using detailed clinical forms filled out by dietitians at each follow-up visit. Dietary information collected included goal calories, daily number of servings required per food group, serving size, and fluid goals. Feeding tolerance was assessed and improvement in feeding tolerance was defined by either decrease in frequency of symptoms, such as vomiting and/or improvement in the ability to advance feedings or reach goal feedings.

Medication Data

Medication information at office visits before and after initiation of BTF was collected including gastrointestinal (GI)-related medications, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPI), H2 blockers, antacids, promotility agents, stool softeners, stimulant laxatives, and enema/suppositories. Relevant symptom information was extracted from physician documentation of the office visit associated with initiation of BTF as well as follow-up visits.

Side-effect Data

Side-effects and adverse events possibly related to BTF including allergic reaction, enteric infection, or aspiration pneumonia were recorded. Length of time on BTF in months and reasons for stopping BTF if the child was no longer receiving BTF were documented.

RESULTS

Baseline Demographics

Thirty-five patients (24 boys) met inclusion criteria. Age at initiation of BTF was 1 to 19 years (mean 8.3 +/− [SD] 5.8 years). The majority of patients were medically complex children with genetic syndromes or cerebral palsy (CP) with intellectual disability (Appendix C, http://links.lww.com/MPG/B926). At baseline 25, patients had normal BMI or weight/length, 8 were underweight, and 2 were overweight.

Baseline Gastrointestinal Diagnoses

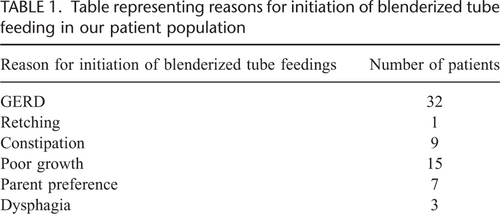

The majority (19/35, 54%) had multiple GI diagnoses. Thirty-three had gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and 10 had constipation. Most had multiple reasons for initiation of BTF, the most common being GERD (32/35, 91%) (Table 1). Seven patients were started on BTF for parent preference, although 6 of these patients also had other reasons.

Baseline Gastrostomy Tube Data

Thirty-three had G-tubes and 2 had gastro-jejunostomy (GJ) tubes. Three had fundoplication surgery. Three underwent dilation of their gastrostomy stoma to receive BTF, 2 from 12 to14 French and 1 from 14 to16 French.

Baseline Formula Regimen

Twenty-one (60%) were not receiving oral feedings at baseline. Most were on bolus feedings (N = 27) or on combination of bolus/continuous feedings (N = 6); 2 with GJ tubes were on continuous jejunal feedings only. Patients were more likely to be on whole protein cow's milk formula (N = 15) or hydrolyzed formula (N = 11). Six patients were on elemental formula, 1 was on soy formula, and 2 were on UltraCare for Kids, which is cow's milk and soy protein free that did not fit into the categories above.

Baseline Medications

Thirty-three patients were on GI-related medications for GERD, constipation and/or upper GI dysmotility. Most patients were on multiple GI medications (N = 19). The most common class of medications were PPI.

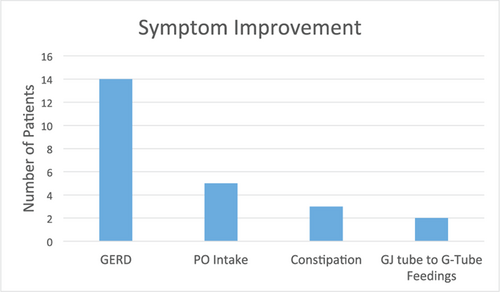

Symptom Results

Twenty-one patients had improvement in symptoms based on documentation at follow- up visits (21/35, 60%). Of note, some had improvement in more than 1 symptom category (Fig. 1). The most common symptoms to improve were those related to GERD. Fourteen of the 33 patients with GERD, and 3 of 10 patients with constipation had improvement in these symptoms, respectively. Five patients reported improvement in oral intake, and 2 were able to be transitioned from GJ to G-tube feedings. Two patients had worsening of symptoms, 1 with worsening constipation and the other with worsening GERD.

Bar graph representing symptom improvement after initiation of blenderized tube feedings. Symptom improvement was documented in physician notes from clinic visits through caregiver report. Number of patients is represented on the y-axis and symptom category is represented on the x-axis. Total number of patients in our cohort was 35. Of note, some patients did have symptom change in more than 1 symptom category.

Medication Results

Thirteen of the 33 patients on GI-related medications were able to stop or decrease these medications. Ten on acid-suppressive and/or promotility agents and 3 patients on stool softeners or stimulant laxatives were able to wean or stop these medications. Three patients added or increased GI medications. One patient started a stool softener for worsening constipation. Another increased H2 blocker dosage but overall had improvement in reflux symptoms after achieving full BTF volume. The third patient started a promotility agent for chronic vomiting but vomiting did not improve with either medication change or BTF. Two patients not on baseline GI medications did not start medications.

Diet Results

Most (25/35, 71%) were on a combination of BTF and formula feedings during the study period. Percentage of the diet via G-tube as BTF by volume ranged from 10% to 100%. Twelve patients were not receiving commercial formula feedings via their G-tube, and an additional 6 were receiving <50% of their G-tube feedings (by volume in a 24-hour period) as commercial formula by the end of the study period. For various reasons, 15 patients did have commercial formula as part of their BTF recipe. No patients received commercial blenderized products. The length of time on BTF ranged from 1 to 45 months. Mean length of time on BTF was 15 +/− 12.2 months. Of note, 3 patients were able to stop BTF as their oral intake had improved and they no longer required G-tube feedings. Of patients requiring G-tube feedings at the completion of the study period, 29 of 32 remained on BTF. Additionally, 2 successfully transitioned from continuous jejunal feedings via GJ tube to BTF via G-tube.

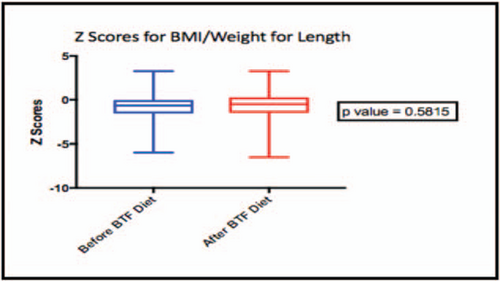

Anthropometric Results

Most patients had relatively stable BMI before and after initiation of BTF. Z scores for BMI (or weight/length) did not differ before compared with after BTF (P value = 0.5815) (Fig. 2). A few patients had changes in BMI category. Two patients went from normal BMI to underweight, 3 went from underweight to normal BMI, and 2 patients went from normal BMI to overweight. BTF recipes were adjusted based on weight gain during the study period. Comparison of total calories per day before and after BTF initiation for each subject demonstrated up to a 10% increase in calories per day after initiation of BTF.

Box plot representing z-scores for body mass index of patients ≥2 years old and weight for length for patients <2 years old, before and after blenderized tube feeding diet initiation.

Adverse Events

Mild adverse events were reported in 5 patients and included abdominal pain, rash, and diarrhea. Three stopped BTF because of adverse events or worsening GI symptoms. One with a diagnosis of GERD had worsening reflux symptoms. This patient was on PPI, which was continued and BTF were stopped. Another patient with diagnoses of GERD and chronic constipation developed diarrhea, and BTF were stopped. Infectious stool studies including bacterial stool culture (Escherichia coli, Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter), C difficile, O&P, Giardia, and fecal leukocytes were all negative. The third patient developed rash presumably related to food allergy; however, the allergen could not be identified, and BTF were stopped. One patient developed a rash after BTF but the allergen was identified as oat, and once removed the patient was able to continue on BTF. No serious allergic reactions or life-threatening adverse events occurred in these patients.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that BTF can improve GI symptoms, consistent with prior studies (1., 2.). In our cohort, the most common symptoms reported to improve were related to GERD, which also was the most common underlying GI diagnosis. Although caregiver opinion in favor of BTF could bias results, more objective measures including medication changes, improved oral intake and feeding tolerance, suggest clinical improvement with BTF in our cohort. Thirteen of 33 patients who were on GI-related medications were able to wean or stop these medications, and 2 children who had required continuous jejunal feedings were successfully transitioned to BTF via G-tube.

During the 1950–1960s, several studies reported benefits of hydrolyzed proteins and single amino acids to provide adequate nutrition (3.). BTF are, however, made from table foods in which recipes can be individualized to meet all nutritional needs for children or adults. This is particularly relevant today, as there is an increasing population of medically complex children living in the United States, and therefore an increasing prevalence of long-term G-tube feedings (4.-6.). Additionally, BTF are felt to be more natural and can be varied, as would be in an oral diet, aspects which are appealing to caregivers (7., 8.).

Interestingly, 5 patients in our cohort showed improved oral intake after initiation of BTF, and 3 were receiving all feedings by mouth by the end of the study period. Improved oral intake has been demonstrated in other pediatric BTF studies (1., 2.). Kelsey et al proposed theories for this observation including decreased GI symptoms, changes in appetite signaling mediated by changes in intestinal microbiota composition, and increased motivation of caregivers to offer oral food (2.).

Few adverse events and no life-threatening adverse events were observed in our cohort, and the majority of patients were able to continue BTF. Only 3 patients stopped BTF secondary to adverse events; 1 patient because of worsening GERD, another because of rash (attributed to potential food allergen), and the third because of diarrhea. No foodborne illnesses or aspiration pneumonia events were reported. Food preparation courses could be considered as part of an institutional protocol for those offering BTF.

As above, a concern regarding BTF is potential food allergy. Given some patients on G-tube feedings have never been exposed to table foods, potential for food allergy is often unknown. Two patients in our cohort developed rash because of presumed food allergy. In 1 patient, the food allergen was identified, and, once removed from the BTF, the patient did well and was able to continue BTF. The allergen was unable to be identified in the second patient, and ultimately BTF were stopped. No serious allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis was reported. More data would be helpful to guide clinicians in starting BTF especially in children who have not previously been exposed to table foods.

BMI and weight/length z-scores did not differ before and after BTF initiation. This seems to be contrary to recent data published regarding increased calorie needs with BTF compared with commercial formula (2.). Anthropometrics were monitored during the study, and calories provided were adjusted as clinically indicated. Overall no difference was, however, found between calories required before or after BTF. Standard growth charts (CDC or WHO depending on age) were used in all patients in part because of inconsistent activity data reporting and that specific growth charts, such as CP may not fit all patients within our heterogeneous cohort. It is, however, unclear if change in BMI category would have been different using disease-specific growth charts. Larger prospective studies are needed to determine if caloric needs for children on BTF differ from those on commercial formula.

Potential weaknesses of our study include the retrospective nature, small numbers, and variability of BTF. A high degree of variability of BTF was observed as the diet is individually tailored. This is an inherent challenge in this type of nutrition-related research. Additionally, most patients in our cohort remained on a combination of BTF and commercial formula feedings, possibly because of our institution's protocol of gradually advancing BTF over time.

The process of transition can take about 2 months. In addition, some children continued to receive commercial formula because of the inability to receive BTF in school or while hospitalized. Further studies are needed to show if partial BTF provides similar clinical benefits to exclusive BTF.

Strengths of our study included mean length of time on BTF ~12 months and the medical complexity within our cohort. Most of our patients were medically complicated, which may have biased against BTF showing clinical benefit. Our results, however, show the majority of patients had symptom improvement, and many were able to wean GI-related medications after initiation of BTF. The relatively long mean duration on BTF suggests sustained clinical improvement while on BTF.

Recently Gallagher, et al (2.), analyzed microbiome changes through 16S rRNA-based sequencing before and after initiation of BTF in pediatric patients and showed increased bacterial diversity and richness after initiation of BTF. The mechanism(s) through which BTF impacts feeding tolerance and GI symptoms remains, however, unclear and requires further study.

In our experience, BTF is a safe and effective method to provide nutrition in children with G-tubes. Larger prospective studies are needed to evaluate underlying mechanisms for clinical improvement and help target, which patients may benefit from BTF.