Savary Dilation Is Safe and Effective Treatment for Esophageal Narrowing Related to Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal's Web site (www.jpgn.org).

ABSTRACT

Objectives:

Data on management of esophageal narrowing related to eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) in children are scanty. The aim of the present study is to assess the safety and effectiveness of esophageal dilation in pediatric EoE from the largest case series to date.

Methods:

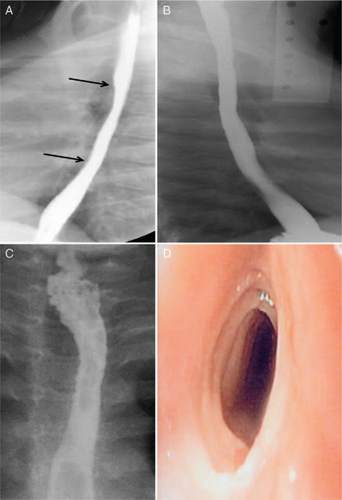

Children diagnosed with EoE during 2004 to 2015 were reviewed for the presence of esophageal narrowing. Esophageal narrowing was categorized as short segment narrow caliber, long segment narrow caliber, and single short stricture. The characteristics of the narrowed esophagus, therapeutic approach, clinical outcome, and complications were reviewed.

Results:

Of the 50 EoE cases diagnosed during the study period, 11 cases (9 boys; median age 9 years, range 4–12) were identified with esophageal narrowing (22%). Six had short segment narrow caliber esophagus and 5 had long segment narrow caliber esophagus (median length of the narrowing was 4 cm, range 3–20 cm). Three cases with narrow caliber esophagus also had esophageal stricture 2 to 3 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter. Nineteen dilation sessions were performed in 10 cases using Savary dilator. Esophageal size improved from median 7 mm to median 13.4 mm. Good response was obtained in all cases. Following the dilation procedure, longitudinal esophageal mucosal tear occurred in all cases without esophageal perforation or chest pain.

Conclusions:

Esophageal dilation using Savary dilator is safe and highly effective in the management of esophageal narrowing related to EoE in children. Dilation alone does not improve the inflammatory process, and hence a combination with dietary or medical intervention is required.

What Is Known

- Esophageal narrowing is an uncommon complication of eosinophilic esophagitis.

- The esophageal mucosa in eosinophilic esophagitis is prone to tears.

What Is New

- Savary dilation is safe in the management of eosinophilic esophagitis-associated esophageal narrowing.

- The high incidence of esophageal narrowing indicates that esophageal narrowing is not an uncommon complication in longstanding, untreated pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis.

- The high consanguinity rate among children with eosinophilic esophagitis-associated esophageal narrowing may indicate that a subset of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis who have a genetic predisposition to stricture formation.

- Dilation alone does not improve the inflammatory process, and hence a combination with dietary or medical intervention is required.

Esophageal narrowing resulting from eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) presents significant management challenges. The esophageal mucosa in EOE is fragile and prone to extensive esophageal mucosal tears following esophageal dilation, so-called crepe-paper mucosa (1.). There are a number of reports describing spontaneous esophageal perforations and perforations caused by instrumentation of the esophagus in patients with EoE (1.-5.). Cohen et al (5.), in an audit study, reported complications in 31% and a perforation rate of 8%, associated with endoscopy and dilation of esophageal narrowing in adults with EoE. These reports were extremely concerning and raised the question of whether dilation should be considered as a treatment strategy in EoE. This is in striking contrast to a single perforation following 486 dilations for esophageal peptic strictures (0.2%) (6.). Hence, gastroenterologists have been cautioned that patients with EoE may be exceptionally predisposed to perforation with esophageal dilation.

Esophageal narrowing complicating EoE is more frequently encountered among adults with EoE compared with children, therefore the vast majority of the data on EoE-associated esophageal narrowing and its management came from adult studies (7.-10.). There is scanty data on the frequency of esophagus narrowing among children with EoE, and including the management options of this complication (11.-13.). Details on how to deal with this complication were reported in only 2 small cases series that described 6 adolescents (12., 13.); esophageal stenosis was dilated using balloon dilator in 4 cases and bougie dilator in 2, without reports of complications. In light of the scarcity of data, the recommendations of an EoE-expert group from North America and Europe (14., 15.) on management of EoE-associated esophageal narrowing in children indicate that the optimal role of dilation as therapy of EoE is still controversial and that dilation should only be tried in highly selected cases with severe esophageal narrowing unresponsive to other forms of treatment.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the frequency of esophageal narrowing and to assess the safety and effectiveness of esophageal dilation in children with EoE in a tertiary care center.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study to identify all patients who were diagnosed with EoE in our institution from April 2004 to December 2015. From these cases, those associated with esophageal narrowing, stenosis, and/or stricture were included in the study. Demographic data, clinical symptoms, history of atopic diseases, results of laboratory tests, barium esophagogram, 24-hour pH study monitoring, endoscopic findings, histopathologic features, allergy testing (skin prick test [SPT], radio-allergen sorbent assay test [RAST], and total IgE), and results of treatment were collected and analyzed. The methodology of allergy tests and our practice of using RAST/SPT as guidance for allergen elimination have been described previously (16.). Food impaction was defined as an event occurring after food ingestion during which solid food was retained in the esophagus and the food bolus took more than half an hour to pass after drinking water or a visit to an emergency room was required. Failure to thrive was defined as weighing less than the third percentile for each patient's age and sex. Peripheral eosinophilia was defined as >400 eosinophils/mm3.

Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

The diagnosis of EoE was based on the demonstration of isolated eosinophilic infiltration of esophageal mucosa with at least 15 eosinophils in at least 1 high-power field (HPF), and without symptomatic or histologic response to proton pump inhibitor therapy (PPI). All of the patients were receiving PPI at the time of endoscopy, for a variable period of time that ranged between 1 and 6 months. PPI had been prescribed by either family physicians or treating gastroenterologist for suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease. During upper endoscopy, 2 biopsies were obtained each from the distal, upper, and mid-esophagus, as well as the antrum and the duodenum. All biopsies were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The number of eosinophils in the most densely involved x400 microscopic HPF was counted, which included the eyepiece magnification, and the area of the microscopic field was equivalent to 0.22 mm2. Each esophageal specimen was evaluated for the presence of degranulated eosinophils (defined as free eosinophil granules in the esophageal epithelium) and eosinophil clusters (defined as ≥5 eosinophils clustered together). Submucosal fibrosis describes the scarification processes that occur in lamina propria, mainly the subepithelial layer from 70 to 150 microns immediately beneath the epithelium. Fibrosis was assessed in each esophageal biopsy specimen by Masson trichrome staining, hematoxylin and eosin, or both on light microscopy by quantifying the amount and thickness of collagen bundles.

Evaluation of Esophageal Narrowing

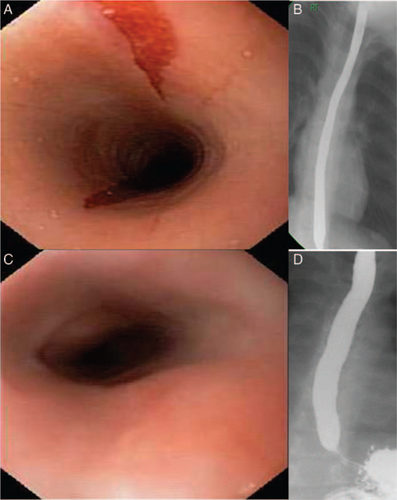

We have adopted an approach of carefully evaluating the esophagus for narrowing in children with severe dysphagia/food impaction and suspected EoE by performing barium esophagogram within a week before upper endoscopy. For description regarding the narrowed region, the esophagus was divided into proximal (cervical to T2 level), mid (T3–T6), or lower (T7 to thoracolumbar junction) esophagus. The term “esophageal stricture” was used to describe a very short focal stenosis (length up to 1 cm). The term “narrow caliber esophagus” was used to define either short segment narrow caliber if the narrowing was limited to one third of esophagus or “long segment narrow caliber” if the narrowing involved more than one third of esophagus. Esophageal narrowing was further evaluated endoscopically regarding the length and diameter of the stenosis as well as the number of and time duration between dilation sessions. The severity of stenosis was graded into 3 groups as follows: “low-grade stenosis” that allows passage of standard pediatric upper endoscope (outer diameter 8.6 mm) with little resistance; “intermediate-grade stenosis” that allows passage of the neonatal endoscope (outer diameter 6 mm) but not of a standard upper endoscope; and “high grade stenosis” that does not allow passage of a 5.9 mm neonatal endoscope.

Dilation Procedure

Endoscopy was done in all of the patients by a single endoscopist under general anesthesia, with tracheal intubation and mechanical respiratory assistance. Savary-Gilliard hollow-centered dilators were used to dilate esophageal narrowing over an endoscopically placed spring-tipped guide wire under fluoroscopy. The size of first dilator used was chosen based on the initial endoscopic assessment of luminal caliber. In grade 1 “low-grade stenosis,” a 9-mm dilator size was selected. In grade 2 “intermediate-grade stenosis,” a 7-mm dilator size was initially used for dilation. In grade 3 “high grade stenosis,” a 5-mm dilator size was chosen to start with. We used an increment of 3 mm per dilation session (with intervals of 4–6 weeks), with a target esophageal diameter of 12.8 mm in young children younger than 5 years and up to 14 mm in older children. In addition to passage of a dilator, it is our practice to perform endoscopic reinspection of the esophagus (immediately after dilation) to determine whether the dilation has resulted in esophageal mucosal trauma along with its location, extent, and severity, and to obtain esophageal biopsies. The patients were hospitalized for endoscopy and dilation and discharged after 24 hours unless there was acute bleeding, perforation, or another complication.

Other Treatment

After dilation procedure, all patients were treated with swallowed aerosolized fluticasone propionate from a metered dose inhaler at a dose of 250 μg twice daily for children younger than 10 years and 500 μg twice daily for children older than 10 years. This dose was dispensed for 2 months before starting to taper the dose to 125 μg twice daily, as a maintenance therapy. In practice, patients were instructed to swallow the agent, which was sprayed into the mouth with a metered dosed inhaler without a spacer, and not to eat or drink for at least 30 minutes after administration. Patients were advised to rinse their mouths out with water to prevent oral candidiasis. In addition to topical corticosteroids, foods identified on allergy tests (RAST and SPT) to be allergic were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary clinical outcome used to measure response to esophageal dilatation was the improvement of clinical symptoms (dysphagia and frequency of food impaction) after all dilation sessions were completed and the need for subsequent esophageal dilation during follow-up. Good response was defined by resolution of the clinical symptoms. Partial response was defined by improvement in the clinical symptoms, and no response defined as persistence of the clinical symptoms. We reviewed medical records (clinic or endoscopy notes) to assess the clinical symptom response to dilation. Other outcome of interest was the histopathological improvement in eosinophilic esophageal infiltrate. Patients with mean eosinophil count 0 to 5 per HPF in the repeated esophageal biopsies after 6 weeks of therapy were considered to be in histologic remission. Those patients with mean eosinophil count 5 to 14 per HPF and improvement of symptoms were considered to be in partial remission. An eosinophil count 15 per HPF or more was defined as medical treatment failure. Complication was defined as any event after dilation procedure with a negative impact on the subsequent course of the patient such as occurrence of bleeding, perforation, infection, and chest pain.

The study was approved by the local ethics review board (IRB log number 12-276).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 21.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and percentages) were used to describe the quantitative and categorical study variables. Student t test for independent samples was used to compare the mean values of quantitative variables. Pearson chi-square test and Fisher exact test were used to observe an association between categorical study variables and presence of esophageal narrowing. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 50 pediatric EoE cases diagnosed during the study period, 11 cases (9 boys; median age 9 years, range 4–12) were identified with esophageal narrowing (22%), which constituted 14% of the total 80 cases of esophageal stenosis presenting to our center during the study period. Table 1 shows the clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic characteristics of the 11 cases of EoE with esophageal narrowing compared with the 39 cases of EoE without esophageal narrowing. Twenty four-hour pH study monitoring was performed in patients 5 to 10; reflux index was normal (<4%) in all except in patient 5 (reflux index = 7.5%). Nine children underwent RAST and SPT. Sensitization to foods (specific IgE for the suspicious food) was demonstrated in 7 patients (64%); the most common food allergens were wheat, nuts, and soybean (7 patients), followed by milk (4 patients), egg (3 patients), almond (2 patients), fish and sesame (1 patient each). Total serum IgE was elevated in 7 patients (median 602 Ku/L; range 309–1436 Ku/L; normal <100 Ku/L). In addition to food allergy, patient 3 also was sensitized to aeroallergens such as pollens and mites. Only in 2 patients, lamina propria was available in an adequate amount to assess for fibrosis; subepithelial fibrosis was present in both patients.

Characteristics of the Esophageal Narrowing

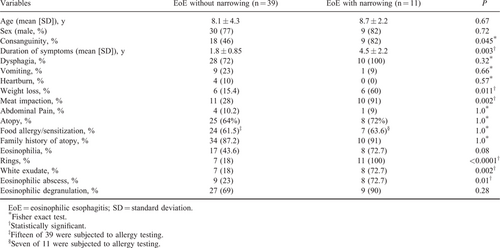

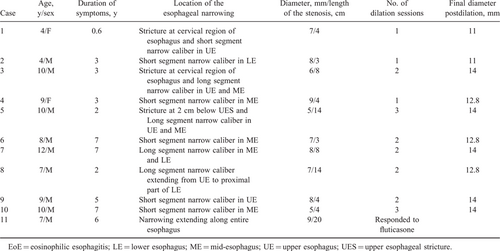

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 11 patients with EoE and esophageal narrowing. Six had short segment narrow caliber esophagus (3 in mid-esophagus, 2 in upper esophagus, and 1 in lower esophagus) (Fig. 1A) and 5 had long segment narrow caliber esophagus (3 in upper and lower esophagus and 1 in mid and lower esophagus) (median length of the narrowing was 4 cm, range 3–14 cm) (Fig. 2). The esophageal narrowing was “high-grade stenosis” in 3 patients, “intermediate-grade stenosis” in 6, and “low-grade stenosis” in 2. Three cases with narrow caliber esophagus also had esophageal stricture 2 to 3 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter (Fig. 1C, D) whereas in 7 cases, barium esophagogram and endoscopy demonstrated a uniformly narrow esophageal lumen. Patient 4 had a subtle “low grade” narrow-caliber esophagus unrecognized on barium esophagogram, and esophageal narrowing was noticed during endoscopy. In all cases, esophageal narrowing was diagnosed at the time of diagnosis of EoE except in patient 1 who developed esophageal narrowing 3 years after diagnosis of EoE at 1 year of age when the patient lost follow-up before presenting again at 4 years of age. Nineteen dilation sessions were performed in 10 cases using Savary dilator. Esophageal diameter size improved from median 7 mm to median 13.4 mm (Fig. 1A, B; Fig. 2B, D). Following the dilation procedure, longitudinal esophageal mucosal tear occurred in all cases (Supplemental Digital Content, Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A676) without esophageal perforation or chest pain. The longitudinal mucosal tears ranged from 3 to 14 cm in length corresponding to the length of esophageal narrowing. In patient 11, the last patient that had been seen in our study cohort in mid of 2015, we opted to give a trial of swallowed fluticasone inhaler for 3 months before the dilation attempt. The response to medical therapy in this patient was a dramatic improvement clinically, radiologically, endoscopically, and histologically (Fig. 2C, D).

A, Lateral view for a barium esophagogram in patient 6 shows a short segment narrow caliber esophagus involving mid-esophagus (between the 2 arrows). B, Lateral view for a barium esophagogram in the same patient following 2 sessions of dilation. C, Barium esophagogram in patient 3 shows a focal stricture at 3 cm below upper esophageal sphincter (upper arrow) and a long segment narrow caliber esophagus involving both upper esophagus and mid-esophagus. D, Endoscopic view for the focal stricture in the same patient. It demonstrates a multiple, fixed, closely spaced, concentric rings traversing the stricture.

A, Endoscopic view of a 2 longitudinal mucosal tears developing during passage of a pediatric endoscope (diameter size 8.6 mm) in patient 11. B, Frontal view for a barium esophagogram in patient 11 shows narrowing of the entire course of esophagus. C, Improved endoscopic appearance of the esophagus following 3 months of therapy with swallowed inhaled fluticasone. D, Barium esophagogram in the same patient following 3 months of therapy with swallowed inhaled fluticasone.

Treatment Outcome

Good response was obtained in all cases following completion of dilation sessions. All patients received omeprazole (1–2 mg · kg−1 · day−1) for 2 weeks after dilation procedure to help heal the longitudinal mucosal tear. Patient 3 failed to respond to a trial of swallowed fluticasone inhaler for 2 months followed by oral prednisone for another 2 months (1 mg · kg−1 · day−1) before esophageal dilation. Esophageal biopsies obtained at the time of last dilation session revealed remission in 2 patients, partial remission in 3, and failure of medical therapy in 5 despite compliance with treatment.

Follow-up

Two children (patients 5 and 7) had poor compliance to medical and dietary recommendations whose esophageal narrowing and symptoms relapsed within 6 to 8 months after stopping therapy. The remaining 9 patients on maintenance swallowed inhaled fluticasone reported no recurrence of symptoms after a median follow-up period of 3 years (range 0.5–7 years). Patient 9 developed candida esophagitis and treated with oral fluconazole. No adverse effects on patient growth have been observed. The median follow-up period was 2.5 years (range 1–9 years).

DISCUSSION

Our study has several important findings. First, we report the largest pediatric case series on management of EoE-associated esophageal narrowing and show that esophageal dilation using Savary dilator is safe and effective at relieving dysphagia due to narrow caliber esophagus. Second, the good response to dilation occurred despite persistence of eosinophilic inflammation. Third, the high incidence of esophageal narrowing in our cohort (22%) indicates that EoE is not an uncommon complication of long-standing, untreated EoE, even during childhood.

Esophageal narrowing complicating EoE is more frequently encountered among adults. Esophageal strictures were reported in 25% of adults with EoE (5.), compared with 6.3% of 381 pediatric patients with EoE (11.). One possible explanation of this difference in incidence is that esophageal narrowing may be underreported in pediatrics because often it is seen in the early stages only on esophagogram (17.), which is not routinely performed before endoscopy in children owing to the burden of radiation, in contrast to adults who perform the contrast study to look for tumors before endoscopy. Another possible explanation is that the esophagus in EoE passes through 2 phases, an “inflammatory phase” in young children, that if left untreated can result into a “fibrotic phase” in older children and adolescents (18.-20.). Ultimately, progress of fibrosis of esophagus leads to a narrow esophagus and eventually food impaction. This possibility is corroborated by the findings in our study that the duration of symptoms preceding the diagnosis of EoE was longer in patients who developed esophageal narrowing compared with those without narrowing (4.4 ± 2.2 vs 1.8 ± 0.85 years) and the significant increased frequency of rings formation in patients with esophageal narrowing (100% vs 18%). Rings formation has been frequently reported in association with fibrosis (18.). The high incidence of esophageal narrowing (22%) in our relatively young pediatric cohort (median age 9 years, range 4–12) suggests that this progressive process may evolve rapidly in some children. An alternative explanation is that there are different phenotypes of EoE. Local data from Saudi Arabia further support our findings and report esophageal narrowing among 13% (21.) and 28% (22.) of Saudi children with EoE. The significant frequency of consanguinity among children with EoE and esophageal narrowing in our study (82%) may indicate that a subset of patients with EoE may have a genetic predisposition to stricture formation as has been suggested (23.). Our data indicate that the clinical phenotype of EoE that could predict esophageal narrowing was characterized by long duration of symptoms before diagnosis, food impaction and weight loss on presentation, and rings formation on endoscopy. Further research is required to determine the phenotype/genotype of patients with EoE at risk for developing extensive remodeling and strictures and for whom early intervention with topical fluticasone or dietary therapies may prevent stricture formation.

As a result of increased frequency of esophageal narrowing among adults with EoE, the vast majority of data on management of esophageal narrowing and safety of dilation came from adult patients (5., 7.-9.). Earlier reports raised the question of whether dilation should even be considered as a treatment strategy in EoE (1.-5.); however, larger recent studies suggest that dilation can be used safely and effectively (24.). A systematic review of literature on esophageal dilation in EoE revealed 468 patients who underwent a total of 671 endoscopic dilations (25.). Esophageal mucosal tears and chest pain were described in most cases, but there was only 1 perforation among the 671 dilations (0.1%). We searched PubMed and Medline between 1990 and 2014 for English-language articles published on management of “esophageal narrowing/stricture” associated with “pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis.” We included only those reports that provided details of esophageal narrowing, dilation procedure, and complications. Only 2 small cases series fulfilled these criteria (Supplemental Digital Content, Table 1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A677); they described 6 adolescents who underwent effective and safe esophageal dilation. The finding of extensive, longitudinal mucosal tear of the esophageal body after dilation was common to these 6 cases and the 10 cases in our study. Such mucosal tear is an anticipated outcome of effective esophageal dilation and therefore we have not considered it as a complication of the dilation procedure. Documentation of the extent of longitudinal mucosal tear has provided useful information about the length of esophageal narrowing.

There is no consensus whether dietary elimination, steroids, or combinations of both should be tried first and for how long in a child with EoE-associated esophageal narrowing before it is deemed a failure of medical treatment and resorting to esophageal dilation. Our study and others (7., 8., 26.) clearly showed clinical resolution of dysphagia symptoms, and this was independent of the degree of eosinophil infiltration, which was unchanged in most of the patients after dilation. This discrepancy suggests that dysphagia in EoE results not only from eosinophilic inflammation but also from established esophageal narrowing. Dilation alone clearly, however, does not improve the underlying inflammatory process that, if left untreated, can result in fibrosis and recurrence of esophageal narrowing as transpired in 2 of our patients who did not comply with topical steroids. Recent reports that suggest that esophageal fibrosis and remodeling may be reversible in children treated with topical steroids (23., 27., 28.) have encouraged us lately to change our practice of dilating first, assuming that esophageal dilation is often necessary to correct fixed stenosis, to a more conservative approach of trying medical therapy first followed by dilation if medical therapy fails. This strategy was successful in 1 case (patient 11) and failed in another (patient 3). Whether topical steroids should precede or follow esophageal dilation is unknown, a question that needs to be addressed in future studies. Until further evidence is available, we propose a trial of topical steroids for 3 months; if this trial fails to relieve dysphagia then dilation becomes necessary. We opted for the 3-month duration because previous work suggests that fibrosis may be diminished within 3 months of topical steroid treatment (23., 27., 29.). Following dilation to relief dysphagia, we recommend to continue on topical steroids to suppress the underlying eosinophilic inflammation and retard remodeling.

Based on the safety and effectiveness of the dilation procedure in our case series, we propose to start with a small diameter Savary dilator (based on the grade of esophageal stenosis) with an increment of 3 mm per dilation session (with intervals of 4–6 weeks), with a target esophageal diameter of 12.8 mm in children younger than 5 years and up to 14 mm in older children. This degree of esophageal luminal patency will allow patients to eat a modified regular diet. The more severely narrowed esophagus (resistance to passage of a neonatal endoscope) will require 2 to 3 dilation sessions. In concordance with several reports in adults (7., 8., 25., 28.), the use of Savary dilator was our choice for various reasons. First, esophageal narrowing in the setting of EoE usually extends for longer than a segment and sometimes diffusely; balloon dilatation provides only segmental benefit at best, whereas Savary dilators can dilate through the entire length of the esophagus. Second, esophageal strictures in EoE can be located just below the upper esophageal sphincter, as was the case in 3 of our patients, making endoscopic through-the-scope balloon dilation difficult in some cases in view of the limited distance between the tip of the endoscope and the stricture. Third, Savary dilators give a better tactile assessment of lumen narrowing than balloon dilator. In addition, balloon dilators add cost to the dilation procedure compared with reusable Savary dilators.

Our study has some limitations. The first limitation is the retrospective design; however the dilation procedures being performed by a single pediatric endoscopist has standardized the methodology of dilation and desired diameter for esophageal dilation thus eliminating operator bias. Because all of the 10 patients received swallowed fluticasone inhaler after dilation procedure, we could not separate the effects of dilation alone from effects related to medical treatment. Because 6 of the 10 patients, however, failed medical therapy, we believe that the symptoms response is due to effective dilation.

In conclusion, esophageal dilation using Savary dilator is safe and highly effective in the management of esophageal narrowing associated with EoE in children. Dilation alone does not improve the underlying inflammatory process, and hence a combination with dietary or medical intervention is required.