Malignant conversion of benign right ventricular outflow track ventricular tachycardia 18 years post-ablation

Abstract

This case report describes the rare phenomenon of malignant conversion of benign right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia into idiopathic ventricular fibrillation 18 years after successful ablation, in the absence of any type of heart disease. We review the current literature looking at predictors for this event, with the conclusion that there are no reliable risk predictors available. Until clear guidelines exist, we suggest patients be informed and monitored for the possibility of “malignant conversion” following ablation for benign idiopathic outflow tract ventricular tachycardia.

1 Patient presentation

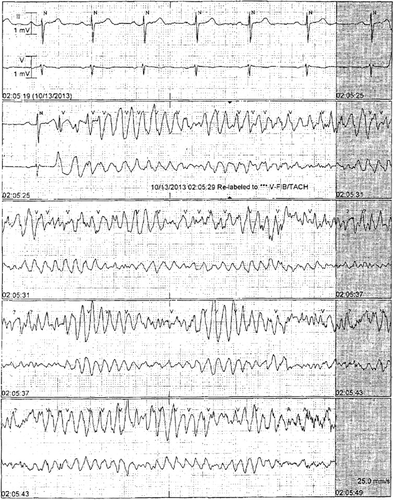

A 64-year-old male with a history of a right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia (RVOT-VT) ablation presented from an outlying hospital due to four recent episodes of non-exertional syncope. He had three witnessed episodes at home but did not receive medical workup until he presented to an outlying ED after the fourth episode. He was sitting at home and became unresponsive for 2–3 min and awoke confused. Patient reported a 2–3 s prodrome of dysphoria. In the ED on telemetry a fifth syncopal episode occurred, lasting 102 s. He was in ventricular fibrillation (VF) without evidence of QT prolongation (Fig. 1). He awoke with normal vital signs and normal sinus rhythm.

Presentation telemetry strip 2013.

The patient was healthy, took aspirin and simvastatin, and had an unremarkable family history. Admission labs and imaging were normal. ECG showed sinus bradycardia, left anterior fascicular block, and a QTc (Bazett's formula) of 407 milliseconds (ms). An echocardiogram was normal. The patient had a normal left heart catheterization. The patient was brought to the electrophysiology (EP) lab where programmed and overdrive stimulation were performed with and without adrenergic stimulation. Despite aggressive pacing protocols from multiple sites using isoproterenol no ventricular arrhythmia or premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) could be induced. A diagnosis of idiopathic VF was made. He received a dual chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and was discharged. To date he has received one appropriate shock for VF which occurred during sleep. Interrogation of the ICD revealed an early coupled PVC initiating coarse VF. Computed tomography angiography was negative for signs of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.

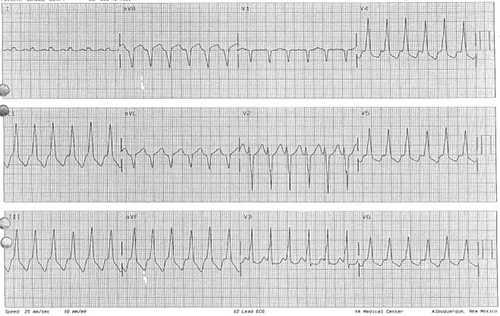

At age 46 he was diagnosed with RVOT-VT after presenting with near syncope with exercise. A stress test revealed non-sustained runs of ventricular tachycardia (Fig. 2). ECG and echocardiogram were normal. The RVOT-VT ablation was straightforward with no complications. He was symptom-free until this admission 18 years later.

RVOT-VT 1996.

2 Discussion

Idiopathic VT originating from the RVOT in patients without structural heart disease is typically benign. Our case represents a clinical syndrome in which younger patients presenting with RVOT-VT and undergoing successful ablation may present later with life-threatening idiopathic VF.

Noda et al. [1] describe the outcomes in five patients undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and polymorphic VT. In all five patients episodes of syncope, VF, and cardiac arrest were eliminated. The authors discuss the possibility of a malignant entity of idiopathic VF or polymorphic VT arising from the RVOT. Willems et al. [2] review the mapping and ablation of VF. They note the spontaneous variation of the PVC occurrence and the demanding transaortic or transseptal mapping approach. The authors recommend performing the EP study acutely after the polymorphic VT/VF event due to the increased presence of PVCs.

Viskin et al. [3] described three patients presenting with benign RVOT-VT who then developed malignant polymorphic VT or VF. The coupling intervals (CIs) of their patients with short coupled RVOT-VT were “intermediate,” significantly shorter than the values seen with uncomplicated RVOT-VT but longer than the values observed in idiopathic VF. Knecht et al. [4] reviewed 38 patients presenting with idiopathic VF. Patients with triggering PVCs originating from the RVOT showed a CI of 355±23 ms versus 276±22 ms (p<.001) for those PVCs originating from the Purkinje system. Shimizu [5] reviewed distinguishing characteristics of malignant forms of RVOT-VT, showing that the shorter coupling interval of initiating PVCs correlated with the more malignant form of RVOT-VT. Noda et al. looked at risk predictors suggesting that malignant RVOT-VT has a significantly shorter cycle length (CL) than benign RVOT-VT (245±28 vs. 328±65 ms, p<.0001) [1].

3 Conclusions

Our case raises the questions: Are patients with outflow tract VT ever completely free from the possibility of developing malignant VT or VF? Are there clinical markers that may be utilized to monitor patients following successful outflow tract VT ablation? The literature does not yet support key differentiating characteristics between benign RVOT-VT and rhythms that are susceptible to undergo ‘malignant conversion.’ Until clear guidelines exist, we suggest these patients be informed and monitored for the possibility of “malignant conversion” following ablation.

Conflict(s) of interest

None.