Inadvertent puncture of the aortic noncoronary cusp during postoperative left atrial tachycardia ablation

Abstract

Transseptal catheterization has become part of the interventional electrophysiologist's technical armamentarium since the development of left atrial catheter ablation and percutaneous technologies for treating mitral and aortic valve disease. Although frequently performed, the procedure's most feared complication is aortic root penetration. Focal atrial tachycardia has been described as the most common late sequela of surgical valve replacements. We present a complicated case involving the inadvertent delivery of an 8 French sheath across the noncoronary cusp during radiofrequency catheter ablation for left atrial tachycardia originating from the mitral annulus in a patient with prior mitral valve replacement.

1 Introduction

Focal left atrial tachycardia (AT) is the most common late sequela of surgical valve replacements. Because sites of origin vary between patients, localizing the AT focus usually requires activation mapping during an ongoing episode of AT. Therefore, AT ablation can take longer than ablation of supraventricular tachycardias. AT originating from the mitral annulus (MA) is rare, and arrhythmia localization using three-dimensional electro-anatomic mapping facilitates its ablation [1].

Safe transseptal puncture and access to the left atrium provide a gateway for emerging technologies and therapies, including left atrial (LA) ablation, LA appendage and ventricular assist devices, and percutaneous valve replacement and repairs. However, aortic root penetration is the most feared complication of transseptal puncture. Since the technique relies on fluoroscopic landmarks to identify anatomical boundaries, a comprehensive understanding of regional anatomy is critical to perform transseptal puncture safely and anticipate difficult situations where complications may arise. The presence of copathologies, including previous interventions on the atrial septum, dilated atria, kyphoscoliosis, dextrocardia, or prior heart surgery have varying degrees of anatomic atrial distortion resulting in fossa ovalis displacement [2] and representing a challenge to transseptal puncture due to movable traditional landmarks. Here, we present an inadvertent noncoronary cusp (NCC) puncture during radiofrequency catheter ablation of left AT originating from the MA in a patient with prior mitral valve replacement (MVR).

2 Case Report

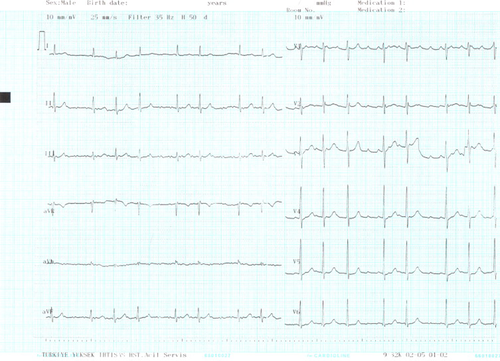

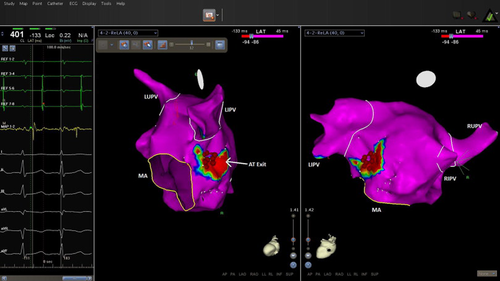

A 57-year-old man with dilated cardiomyopathy and chronic heart failure, who had undergone MVR two years prior, was referred to our department for a second attempt at radiofrequency catheter ablation for refractory incessant atrial tachycardia (Fig. 1). Electrophysiological study (EPS) diagnosed left sided AT. Due to the prior MVR, we continued oral anticoagulation with a therapeutic INR during ablation for peri-interventional anticoagulation management. Because of a coronary sinus catheter placed from the left femoral vein via a 7 French sheath, we preferred the right femoral vein for the transseptal puncture using a Brockenbrough needle and an SL1 sheath. We administered heparin immediately after transseptal access has been safely achieved, avoiding transseptal puncture-related potential pericardial effusion. The contrast medium was injected through the transseptal needle to prevent an inadvertent puncture of adjacent tissues; however, the procedure was stopped prematurely because of inadvertent aortic root puncture resulting from unexpected aorta jumping (Video 1). Emergency surgical consultation recommended sheath removal to reduce the likelihood of tamponade. Because the patient was stable and without hemodynamic sequelae, Amplatzer occluder device use was preferred over open-heart surgery for percutaneous repair. However, after removing the dilatator from the aortic root, there was no regurgitation on the transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) and aortic root angiogram (Video 2), and no oxygen step-up or pressure increase in the right atrium. Therefore, the patient was followed up conservatively in the catheterization laboratory with serial echocardiographic examinations that showed no evidence of aortic regurgitation or pericardial effusion (Video 3). The patient was followed up in the coronary care unit, where he remained stable without hemodynamic sequela for 2 days. Echocardiographic examinations remained normal. Two days later, the patient underwent EPS again. Transseptal puncture was performed successfully under TEE guidance confirming appropriate catheter positioning via a tent-shaped deformation of the interatrial septum. First, the right atrium was mapped, and the earliest activation was on the septal area. The activation time was at approximately zero when compared to the reference catheter in the coronary sinus ostium. The electro-anatomic fast activation mapping showed a focus on the posterior LA wall under the left inferior pulmonary vein ostium (Fig. 2), and the ablation terminated the incessant AT at this point. There was no retroperitoneal hematoma or peritoneal effusion immediately after the procedure or the following day, and the patient was discharged. Three months later, he was in sinus rhythm and off medication with no evidence of aorta–right atrial shunt.

Electrocardiography showing incessant atrial tachycardia.

Sequence of left atrial activation using electro-anatomic mapping during atrial tachycardia showing the exit site of atrial tachycardia with the earliest point shown in red. This spot was inferoposterolateral in relation to the mitral annulus. The activation time in the posterior wall and below the left inferior pulmonary vein was −133ms (shown in red) compared to the reference catheter at the coronary sinus ostium. The ablation sites are shown as red dots. AT, atrial tachycardia; MA, mitral annulus; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; LUPV, left upper pulmonary vein; RIPV, right inferior pulmonary vein; RUPV; right upper pulmonary vein.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.joa.2014.11.004.

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article Video 1, Video 2, Video 3.

3 Discussion

In the electrophysiology setting, increased pericardial effusion or tamponade risk is associated with left-sided arrhythmia ablations, biventricular pacemaker placements, and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Incisional ATs occur frequently in patients with previous corrective surgeries for congenital heart defects and mitral valve disease, and often necessitate transseptal catheterization. Reported complication rates of 1% relate to aortic puncture or left/right atrial free wall perforation [3]. Puncture into the NCC can be recognized by contrast medium injection and changes in the pressure waveform. If this complication goes unrecognized and the sheath advances into the aortic root, surgical repair is usually mandated. However, in this case, we managed the patient conservatively without the need of surgical or percutaneous closure. We used a structured approach with pre-procedural identification of challenging anatomical substrates, and all diagnostic tools available to minimize complications. Fluoroscopic views of the catheter position should be at approximately 45° on the left anterior oblique (LAO) view and inferior and posterior to the pigtail catheter in the aortic root on the right anterior oblique (ROA) view. However, no specific angle in the RAO or LAO projections will be anatomically consistent in all patients, particularly those with prior heart surgery.

Pericardiocentesis is a lifesaving procedure and a core competency for all laboratories performing invasive cardiac surgeries. The clinical presentation spectrum is wide, varying from asymptomatic cases to serious hemodynamic compromise and death. However, early recognition and management drastically alters prognosis. Intervention is indicated in early hemodynamic stages, once a pulsus paradoxus is noticed, even in the absence of an overall systemic pressure drop. Echocardiography should be performed immediately when tamponade is suspected, upon onset of chest discomfort after TP, even in the absence of hemodynamic abnormalities; early tamponade diagnosis should prompt the surgeon to discontinue intervention and possibly reverse anticoagulation. The transseptal dilator or sheath should never be advanced unless the surgeon is certain that the needle tip is in the LA to prevent creating a larger hole in the atrial wall or aorta.

This case highlights a rare catheter ablation complication with which all interventionists should be familiar. Our interesting finding was that there was no aorta–right atrial shunt after sheath removal from the NCC. It may relate to a “flap” that closed the connection between the aorta and right atrium due to higher aortic pressure. Among patients who experience inadvertent aortic puncture as an acute complication of transeptal procedure, as well as experience surgical or percutaneous closure, those who do not have echocardiographic evidence of a large effusion respond well to initial stabilizing measures including fluids and vasopressors and thus, there appears to be a role for conservative management in such patients [4].

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.