Knowledge and Self-Esteem of Individuals with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1)

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10897-016-0036-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Abstract

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is a progressive genetic disorder characterized by physical findings such as café-au-lait macules, Lisch nodules, and neurofibromas in addition to other medical complications. Learning and social problems are more prevalent among individuals affected with NF1. It has been reported that people with NF1 have lower self-esteem (SE) when compared to the general population. Additionally, a study published over 20 years ago found that overall knowledge of NF1 was lacking in individuals affected with the condition. The goals of our study were to evaluate NF1 knowledge in adolescents and adults with the condition, as well as to determine if there is a link between patient knowledge and SE. Furthermore, we explored the impact of other factors, such as attendance at a NF1 support group and having a family history of NF1, on knowledge and SE. A survey comprised of knowledge-based questions and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was distributed to individuals with NF1 through the Texas NF Foundation. Overall, the 49 respondents (13 to 73 years of age) had a mean knowledge score of 77.9 % correct answers. Consistent with previous studies, the SE of our study population was lower when compared to general population norms. Although no correlation between knowledge and SE was observed, SE scores were on average higher if a person reported the following: having friends with NF1 (p = 0.009); attending a NF1 support group (p = 0.006); receiving care at a NF clinic (p = 0.049); or having received genetic counseling (p = 0.008). Further research is needed to better understand the relationship between these factors and SE in the NF1 population.

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis Type I (NF1) is a progressive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the tumor suppressor gene, NF1. It affects 1 in 2500 to 3000 births. Clinical manifestations of NF1 are variable and can include multiple café-au-lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, neurofibromas, and Lisch nodules. Additionally, individuals can have plexiform neurofibromas, optic gliomas, certain types of malignancies, skeletal problems, and hypertension (Williams et al. 2009). The estimated lifetime frequency of severe complications associated with NF1 is 27 % (Zoller et al. 1995). Children and adolescents can also experience learning and peer problems at school as a result of their diagnosis (Krab et al. 2009). Approximately 35 % to 65 % of patients with NF1 have learning difficulties, including deficits in reading, mathematics, language, and memory (Levine et al. 2006). In addition, 50 % of children with NF1 have a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Levine et al. 2006).

While there is limited research on the emotional and psychological effects of NF1, self-esteem in individuals with NF1 has been shown to be lower on average when compared to the general population (Wang et al. 2012). Self-esteem, as defined by Heatherton and Wyland (2003) “is an attitude about the self and is related to personal beliefs about skills, abilities, social relationships, and future outcomes.” Wang et al. (2012) also found that individuals with neurofibromatosis (including NF1, NF2, and schwannomatosis) were more likely to experience depression and anxiety because of their diagnosis. Learning deficits in adults with NF1 have been shown to cause feelings of low self-esteem (Crawford et al. 2015). Additionally, social self-consciousness in women with NF1 has been associated with lower self-esteem (Smith et al. 2013). Moreover, quality of life is negatively impacted in affected individuals with severe medical problems or with more severe external findings of NF1 (Page et al. 2006; Wolkenstein et al. 2001).

Benjamin et al. (1993) investigated level of knowledge of NF1 in affected individuals and found that there was an overall poor understanding of the condition. In fact, knowledge seemed to be reflective of, and even limited to, the patient's personal and/or family's experience with NF1. Factors associated with having a greater level of knowledge of the disorder were: having received genetic counseling, belonging to a higher social class, being diagnosed at a young age, being a member of a support group, having a child with NF1, and when NF1 had influenced reproductive decisions (Benjamin et al. 1993). Additionally, Oates et al. (2013) reported limited disease knowledge in a small, Australian cohort specifically regarding “adult NF1-related medical risks and complications, symptoms that require further medical evaluation, and reproductive implications.”

The current study assessed knowledge of NF1 in adolescents and adults with the condition and measured their self-esteem using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). Correlations between knowledge scores and self-esteem levels were investigated to evaluate associations between participants’ level of knowledge about the condition and self-esteem. We hypothesized that those with greater knowledge of NF1 would have higher self-esteem. Additionally, other factors, such as support group involvement, or a family history of NF1 were also explored, to determine if there were any correlations with knowledge and/or self-esteem.

Methodology

Approval for this study was received by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS)—The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board (IRB Number: HSC-GEN-14-0596).

Participants

The study population consisted of individuals aged 13 years and older with a self-reported clinical and/or molecular diagnosis of NF1. The participants were accessed through the Texas NF Foundation, either through their electronic mail (email) database, Facebook group, or at a foundation-sponsored event.

Instrumentation

The instrumentation used in this study was an investigator-designed, self-administered questionnaire. There were online and paper versions of the questionnaire. The online version was created using REDCap software version 5.9.11. The questionnaire had three main sections: (1) demographic questions, as well as questions focusing on the respondents’ experience of having NF1, (2) knowledge of NF1, and (3) the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). The demographic information collected included: gender, current age, age at diagnosis, ethnicity, educational background, and employment status. The 35-question knowledge portion was designed by the research committee. Fourteen of the knowledge questions were modified from the Benjamin et al. (1993) study, while the remaining questions were added in order to cover additional aspects of the condition. Specifically, respondents were asked to: 1) identify features of NF1, 2) answer true and false questions regarding the variability and progressiveness of the condition, and 3) answer multiple choice questions about the genetics, etiology, recurrence risk and incidence of NF1 and about the management of related health issues. Section three of the survey consisted of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), which is a widely used instrument that provides a reliable and valid measure of global self-esteem. It has been used in numerous studies with a variety of different populations (Gray-Little et al. 1997; Robins et al. 2001). The tool consists of 10 questions that evaluate a person's self-esteem. Each question is graded on a Likert scale with total scores ranging from 0 to 30. Higher scores indicate better self-esteem, while scores less than 15 are associated with low self-esteem and scores between 15 and 25 with average or normal level self-esteem (Rosenberg 1989). The tool was selected for its brevity and ease in scoring.

Procedures

The Texas NF Foundation sent out an email, with a study invitation letter and a link to the survey, to all their members (approximately 1600) on November 4, 2014. Two reminder emails were sent out in December 2014 and January 2015. The survey was available for the participants to complete for approximately three months until February 1, 2015 when data collection ended. The database included email addresses of adults (over the age of 18 years) with NF1 and the parents of individuals under the age of 18 with NF1. A link to the survey was also posted on the Facebook page of the Texas NF Foundation. Additionally, hardcopy questionnaires were distributed at a foundation-sponsored holiday event (“Cookies with Santa”) on December 7, 2014.

Parental consent was obtained for participants under the age of 18 years. In the online version of the questionnaire, parents were prompted to read the consent form and decide whether they wanted their adolescent child to participate in the study. If the parent agreed, the adolescent was instructed to read the consent form and indicate whether or not he/she wanted to participate. Survey instructions emphasized that the adolescent with NF1 was to complete the survey, not the parent. Adult participants indicated consent by agreeing to opt-in to the study prior to beginning the online questionnaire. For the hardcopy version, individuals were asked to read an informed consent document and then provide their signature if they agreed to participate. Participants were able to contact the research team with questions via phone or email, information provided on the study invitation.

Data Analysis

Knowledge scores were calculated by counting each correct answer as one point. The total number of knowledge questions was 35; therefore the highest possible score was 35/35. The knowledge score was reported as a percentage correct for each participant. Self-esteem scores were calculated based on the Rosenberg scale methodology (Rosenberg 1989). Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between the continuous variables for knowledge and self-esteem. A two-sample unpaired t-test was used to examine a potential difference in knowledge score between those in the “low” self-esteem group and those in the “average or above-average” self-esteem group. Two-sample unpaired t-tests were also used to examine potential relationships between one's background or experience with NF1 and that person's level of knowledge or self-esteem. A Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the participant's knowledge score to whether or not they thought they would be able to explain NF1 to a friend. Multivariable linear regression models were fitted to assess the independent effect of various factors on knowledge and self-esteem. All analyses were performed using STATA (v.13.0, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was assumed at a Type I error rate of 0.05.

Results

Study Participants

A total of 115 partial or complete responses were collected through REDCap and 2 complete responses were collected at the “Cookies with Santa” event. Of the 115 online responses, 48 (42 %) respondents had completed all of the relevant sections necessary for inclusion in analysis. One respondent was under the age of 13 and did not meet eligibility criteria and was therefore excluded. The final study population was comprised of 49 participants.

The participants’ ages ranged from 13 to 73, with four under the age of 18. The mean age of respondents was 39.2 years (SD: 16.9). Thirty-nine (80 %) of the participants self-reported their age at diagnosis. The median age at diagnosis was 4 years (range < 1 year through 34 years).

The majority of the participants identified themselves as non-Hispanic white (n = 30, 61 %) followed by Hispanic white (n = 10, 20 %). Approximately two-thirds (n = 33) of the study population had completed graduate school or professional school, college, or some college. Complete demographic information is summarized in Table 1.

| Mean age (N = 49) | 39 years |

|---|---|

| Median age of diagnosis (N = 39) | 4 years |

| Gender (N = 49) | n (%) |

| Male | 17 (35) |

| Female | 32 (65) |

| Ethnicity (N = 49) | n (%) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 30 (61) |

| Hispanic white | 10 (21) |

| Hispanic/Pacific Islander | 3 (6) |

| Black or African American | 2 (4) |

| Other | 2 (4) |

| No answer | 2 (4) |

| Education (N = 49) | n (%) |

| Still in middle or high school | 5 (10) |

| Did not graduate from high school | 2 (4) |

| Graduated high school or GED | 7 (14) |

| In or graduated from a technical school | 1 (2) |

| Some college | 14 (31) |

| Graduated college (undergraduate degree) | 14 (29) |

| Graduate school or professional school | 4 (8) |

| No answer | 1 (2) |

A majority of the participants (n = 37, 76 %) reported problems with learning in school, with 32 % (12/37) of those individuals requiring special education classes. Additionally, 57 % (n = 28) of the participants reported attention difficulties and 23 % (n = 11) reported an official diagnosis of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Self-Perceived Severity

Participants were asked questions regarding self-perceived severity of NF1. The majority (n = 41, 84 %) believed that they had a less severe form of NF1 compared to others with the condition. While 71 % (n = 35) reported NF1 affected their physical appearance, 78 % (n = 38) of the respondents were not embarrassed to go out in public because of their diagnosis. About half (n = 23) reported that they had health problems due to their NF1 diagnosis.

Experience of Having NF1

Participants were asked questions regarding their experience with NF1. Seventy-three percent (n = 36) reported having spontaneous NF1 and 37 % (n = 18) reported having a family history of NF1. Among sources of support and experience with different healthcare professionals, 61 % (n = 30) reported attending a support group for NF1, 49 % (n = 24) had received care at a NF-specific clinic, and 33 % (n = 16) had seen a genetic counselor or had genetic counseling from another source such as a clinical geneticist. When asked about peer relationships, approximately two-thirds (n = 34) indicated that they do not have trouble making friends because of their diagnosis. Almost the entire group (n = 48, 98 %) believed that being informed about NF1 was important.

Knowledge

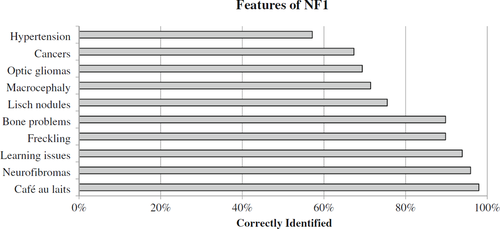

Participants were asked to identify features associated with NF1. Overall, correct identification was high with several features correctly identified over 80 % of the time such as café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, learning problems, freckling in axillary and inguinal regions, and bone problems (Fig. 1).

Features of NF1

Participants were asked a series of true and false questions. Ninety-eight percent (n = 48) of participants correctly understood that it is not their fault that they have NF1. There was also high knowledge of the variability of the condition, with 94 % (n = 46) understanding that NF1 could vary within and between families. The more rare and severe outcomes of NF1, such as cancers and blindness, had the lowest correct scores (Appendix).

There were several other questions covering additional aspects of the condition. Ninety-six percent (n = 47) of individuals knew that NF1 was caused by a mutation in a gene, although only 61 % (n = 30) knew the function of the NF1 gene. Additionally, 90 % (n = 44) chose the correct recurrence risk and 76 % (n = 37) understood that this was the same for each pregnancy. Complete results of the multiple-choice section can be found in the Appendix. Overall, there was good understanding across the majority of the knowledge section, with an average score of 77.9 % (SD: 8.8) correct answers.

In addition, individuals who did not think that they would be able to explain NF1 to a friend had a lower median knowledge score (p = 0.007) and individuals who desired to know more about NF1 also had a lower knowledge score on average (p = 0.043).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

Complete self-esteem scores were collected for 46 (94 %) of the participants. Of these individuals, 22 % (10/46) had low self-esteem (<15) with an average score of 9.5, 57 % (26/46) had average/normal self-esteem (15–25) with an average score of 19.1, and 22 % (10/46) had above-average self-esteem (>25) with an average score of 28.6. The average self-esteem of the study population was lower compared to general population norms (p = 0.0001) (Sinclair et al. 2010). The study population was also stratified by gender and compared to the general population norms; both male and female participants had lower average self-esteem compared to the general population (p = 0.043 and p = 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in self-esteem between male and female participants (p = 0.876).

| Study population | General population* | t value | P- value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | |||

| Overall | 46 | 19.09 ± 6.77 | 503 | 22.62 ± 5.80 | 3.89 | 0.0001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 17 | 19.29 ± 5.31 | 242 | 22.43 ± 6.21 | 2.03 | 0.0432 |

| Female | 29 | 18.97 ± 7.58 | 261 | 22.79 ± 5.41 | 3.45 | 0.0006 |

- *General population norms taken from Sinclair et al. 2010

Factors Associated with Self-Esteem

There were several factors associated with higher self-esteem scores. These included: having friends with NF1 (p = 0.009), attending a support group (p = 0.006), attending a NF clinic for care (p = 0.049), and receiving genetic counseling (p = 0.008). Respondents reporting learning problems was the only factor associated with lower self-esteem (p = 0.023) (Table 3).

| Mean Self-Esteem Score (Range 0–30) ± SD | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you or did you have problems learning in school? | ||

| Yes (n = 37) | 18.2 ± 6.7 | 0.023 |

| No (n = 10) | 23.9 ± 5.3 | |

| Don't know/Don't remember (n = 2) | n/a | n/a |

| Do you have any friends with NF1? | ||

| Yes (n = 13) | 23.4 ± 5.4 | 0.009 |

| No (n = 31) | 17.7 ± 6.7 | |

| Don't know (n = 2) | n/a | n/a |

| Incomplete self-esteem score (n = 3) | n/a | n/a |

| Have you ever been to a gathering or support group for NF? | ||

| Yes (n = 28) | 21.3 ± 5.5 | 0.006 |

| No (n = 18) | 15.7 ± 7.3 | |

| Incomplete self-esteem score (n = 3) | n/a | n/a |

| Have you ever been to a NF clinic (a clinic that specializes in treating people with NF)? | ||

| Yes (n = 23) | 20.8 ± 6.5 | 0.049 |

| No (n = 21) | 16.8 ± 6.6 | |

| Don't know (n = 2) | n/a | n/a |

| Incomplete self-esteem score (n = 3) | n/a | n/a |

| Have you ever had genetic counseling/seen a genetic counselor? | ||

| Yes (n = 16) | 22.4 ± 6.5 | 0.008 |

| No (n = 28) | 16.9 ± 6.2 | |

| Don't know (n = 2) | n/a | n/a |

| Incomplete self-esteem score (n = 3) | n/a | n/a |

Multivariable linear regression models were fitted to determine the independent effects of having learning problems, having friends with NF1, attending a support group, attending a NF clinic, and receiving genetic counseling after adjusting for all the other factors. Based on the regression models, on average, self-esteem scores increased independently by 4.8, 4.7, 4.0, and 4.1 units in the absence of learning problems (95 % CI: 1.4–8.3), having friends with NF1 (95 % CI: 0.7–8.7), attending a support group (95 % CI: 0.2–7.8) or receiving genetic counseling (95 % CI: 0.3–7.8), respectively. Although attending a multidisciplinary clinic was significantly associated with self-esteem in univariable analyses, this factor was not significantly associated in the multivariable models.

Discussion

Knowledge of NF1

The current study aimed to assess NF1 knowledge and self-esteem in individuals with NF1. We hypothesized that those with greater knowledge of NF1 would have higher self-esteem. The study found no association between knowledge and self-esteem. However, we identified the following factors to have an independent positive influence on self-esteem: having friends with NF1, attending a NF support group, and having received genetic counseling.

In the current study, participants’ knowledge of NF1 was overall high, for example, 94 % of our study population understood that NF1 demonstrates both inter- and intra-familial variability and 88 % identified the correct recurrence risk. A previous study done in Benjamin et al. (1993) showed that only 33 % of individuals with NF1 correctly recognized the variability of the disease and only 34 % were able to cite the correct recurrence risk. However, due to the use of different populations and methodologies between this current study and the 1993 one, a direct comparison of knowledge is not possible and we cannot objectively say that there has been an increase in knowledge over the last two decades.

Nonetheless, knowledge level is high in our population and we postulate some factors that may have contributed to the high scores observed. First, there are patient-friendly educational materials available for our target population. For example, in 2005 the Texas NF Foundation (TNFF) published an educational storybook, 14 Stories, for newly diagnosed patients and their families. Second, the increased use of the internet over the last couple of decades has made access to NF1 information easier to obtain. The TNFF has resources for families affected by NF available on their website and membership in the organization is not required for access. Lastly, the phenomenon of “patient activation,” (Alexander et al. 2012) or patients playing a more active role in their healthcare, which requires knowledge of one's condition, could be a factor. Traditionally, the physician had a more paternalistic role, while the patient was more passive about their healthcare. However, there has been a shift to a more collaborative relationship between the patient and the physician (Alexander et al. 2012).

Lower knowledge scores were seen in participants who reported they would have difficulty explaining NF1 to a friend and in those who desired to gain more knowledge about NF1 so that they could explain the condition better to others. These findings are not surprising as we would expect individuals who have difficulty explaining NF1 to have the desire to obtain more knowledge about the condition. Lower knowledge scores in this group could also be due to a potential learning disability or mild intellectual disability. However, with the current study design we were unable to confirm this. The majority (98.0 %) of the study population expressed the importance of acquiring information about NF1. We did not ask participants why they thought knowledge is important and did not specify who (patients, healthcare providers, teachers, peers, etc.) should have this knowledge. From a previous study we know that patient understanding of NF1 symptoms may be vital to ensuring that the individual seeks appropriate medical attention when necessary (Oates et al. 2013). Furthermore, young adults with NF1 desire a greater awareness of NF1 in the general population and medical community to help reduce the number of distressing interactions with others due to misunderstandings (Barke et al. 2013). Given the importance of knowledge for patients, healthcare providers, and others, NF1 education should continue to be a goal of NF1 organizations like the TNFF.

Factors Influencing Self-Esteem

The results of the current study are consistent with previous reports of lower self-esteem in individuals with NF1 compared to the general population (Wang et al. 2012). In addition, our study found that a history of learning problems was correlated with lower self-esteem. We did not find a difference in self-esteem between those who thought NF1 affected their appearance and those who did not. Therefore, perhaps the visible/cosmetic effects of NF1 are not the sole cause of lower self-esteem in this population, but cognitive effects may also play a major role. This finding is in agreement with previous studies reporting that learning and/or attention problems lead to adverse school experiences, resulting in lower self-esteem and damaged self-image in individuals with NF1 (Ablon 2012; Crawford et al. 2015). It is important for parents of children with NF1 to know about the high chance for learning problems so that they can seek intervention at an early age. In addition, informing teachers about NF1 could lead to better support in the classroom.

Several factors were observed to have a positive influence on self-esteem: having friends with NF1, attending a support group, receiving genetic counseling, and attending a NF clinic. We suspect that having friendships with others who have the same diagnosis can help reduce feelings of isolation and lead to an increase in self-esteem. A previous study found that their participants with NF1 either exclusively had friends with NF1, had no friends with NF1, or had a mixture of friends with and without NF1. They found that friends with NF1 were highly valued and helped promote a feeling of being accepted (Hummelvoll and Antonsen 2013).

Similarly, involvement in support groups may help improve confidence of individuals with NF1 by providing long-term support and making individuals affected with a genetic condition or families of affected individuals feel less isolated (“Psychological, and Social Implications,” 2010). Most support groups also aim to provide accurate and up-to-date medical information to their members. In addition, parental participation in support groups can have the positive effect of making a family be more open about discussing the genetic condition, thus helping with family coping overall (Plumridge et al. 2011). This is an important quality of support groups as family members have been described as an essential source of support for individuals with NF1 (Ablon 2012; Barke et al. 2013).

Having received genetic counseling was associated with higher self-esteem. The genetic counseling process can provide an avenue for a person with NF1 to explore coping mechanisms they have developed as a result of their diagnosis or identify ways to improve coping (Gaff and Clarke 2007). Improved coping techniques may partially explain the higher self-esteem scores seen in the current study. Furthermore, genetic counselors are proficient in helping patients with genetic conditions “understand and adapt to the medical, psychological, and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease,” (Resta et al. 2006). Adolescence is a period of developing self-esteem, coping mechanisms, and resilience (Ahern et al. 2008; Holmbeck 2002), and therefore may be a key time to receive genetic counseling. This may be particularly true for individuals with NF1 as adolescence is the time when cutaneous neurofibromas tend to start to appear (Williams et al. 2009). Guidelines published by the National Society of Genetic Counselors on recommendations for counseling patients with NF1 suggested an assessment of how the visible effects of NF1 impacted the affected patient's daily life. This group of genetic counselors also recommended that those providing genetic counseling for patients with NF1 “assist the family in navigating the complexities of special education and/or other interventional services” (Radke et al. 2007). The specialized skillset that genetic counselors have play an important role in helping people with NF1 learn positive ways to cope with their diagnosis, as well as give them room to express their concerns about NF1 and how it affects their relationships with others.

Study Limitations

One limitation of our study is that participants were contacted through a support group organization and were given the option to participate in the study, creating a selection bias and/or self-selection bias. Our population may be different from individuals with NF1 who are not members of a support group, in that they could be more information-seeking or have greater knowledge of the disease, potentially changing the outcome of the study. The possibility of bias along with our small sample size limits the ability for our results to be generalized to the NF1 population as a whole. Also, the wide age range of participants may be a limitation since self-esteem and disease knowledge can change over time. Furthermore, responses to questions about NF1 were based on the “honor system” as it was impossible to control whether or not a participant looked up answers to questions on the Internet. In order to discourage the use of the Internet to search for answers to questions and minimize guessing we provided “Don't know” as an option for each question. Lastly, participants self-reported their diagnosis of NF1, so potentially there could have been participants who did not have NF1 according to current National Institutes of Health (NIH) clinical diagnostic criteria.

Research Recommendations

It would be interesting to investigate level of knowledge of NF1 in groups accessed through other avenues besides support groups, as well as assess whether better knowledge of NF1 is helpful during interactions with peers. Additionally, surveying knowledge of NF1 among different health professionals could help identify ways to increase awareness of the condition in different fields of medicine.

Practice Implications

- Healthcare professionals should inform patients with NF1 about support groups like the Texas NF Foundation. Meeting others who have the same diagnosis could be beneficial for some individuals with NF1. Support groups may also provide a source of reliable information through educational handouts and guest speakers who are experts on NF1.

- This study reaffirms the benefits of genetic counseling for individuals with NF1.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the first author's Master of Science in genetic counseling from University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The authors would like to thank the cooperation and support of the Texas NF Foundation during this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Animal Studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.