Has the Partington procedure for chronic pancreatitis become a thing of the past? A review of the evidence

Abstract

Introduction

For the surgical management of chronic pancreatitis with an inflammatory pancreatic head mass, extended drainage operations such as Beger and Frey procedures were established in the 1980s as an alternative to resectional procedures like pancreaticoduodenectomy and as opposed to simple drainage operations such as lateral pancreaticojejunostomy, that is, the Partington procedure. With the relatively rapid adoption of the two procedures, it seems that the Partington procedure has become a thing of the past.

Materials and methods

The Partington procedure was re-evaluated with regard to the historical aspects and its present status by a literature review.

Results

The results show that this procedure relieves chronic abdominal pain in 66–91% of patients with a mean follow-up of 3.5–9.1 years. It is important to note that this procedure is generally used for inflammatory disease left of the gastroduodenal artery and is specifically not used as the procedure of choice for inflammatory disease of the pancreatic head.

Conclusion

For patients with a dilated main pancreatic duct but without an inflammatory pancreatic head mass, the Partington procedure is still the procedure of choice, since it is technically simple to perform with a minimum of morbidity and mortality, preserving pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function. Because it is a relatively simple technique, the laparoscopic approach will be justified as a treatment of appropriate patients in the near future.

Introduction

Surgical intervention for chronic pancreatitis is required in patients with intractable pain resistant to drug treatment, in those who have developed complications such as biliary or duodenal obstruction, pancreatic fistulae or pseudocysts, and in those in whom malignancy cannot be excluded. Most commonly, operative intervention is directed at pain relief, although the etiology of pain in chronic pancreatitis has not been clarified in detail. It is suggested that perineural inflammation may contribute to production of pain and that a dilated pancreatic duct, secondary to obstruction, may cause pain due to an increased intraductal pressure [1, 2].

Operative procedures to relieve the pain are generally classified as decompressive or resectional surgery. The two approaches were founded on differing pathophysiological theories of the etiology of the pain. Proponents of drainage procedures such as the lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (LPJ), which is also known as the modified Puestow procedure or Partington procedure, insist that decompressing the affected ductal system suffices, whereas proponents of resectional procedures such as pancreaticoduodenctomy insist that removing the portion of pancreas with affected neural tissue, especially the pancreatic head, is mandatory because the pancreatic head is a pacemaker in chronic pancreatitis [3].

Pancreaticoduodenectomies such as the Whipple and the Longmire-Traverso pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy augment pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency for a long-term period, whereas 15–40% of patients do not experience permanent pain relief after drainage operations such as the Partington procedure. Moreover, an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head is considered a contraindication for a simple drainage operation [4]. Therefore, in the 1980s, so-called extended drainage operations such as the Beger [5] and Frey [6] procedures, which are a combination of limited pancreatic head resection and drainage, were established as an alternative to truly resectional procedures like pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and as opposed to simple drainage operations, e.g., the Partington procedure. These two operations, the Beger and Frey procedures, were quickly adopted into practice in Europe, and both procedures have been proven to be equally effective in terms of morbidity, mortality and improvement of pain symptoms in small, randomized controlled trials.

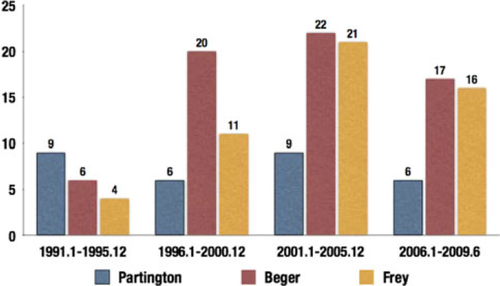

According to a PubMed search from January 1991 to June 2009 using the key words chronic pancreatitis, modified Puestow, Partington, Beger and Frey procedures, the numbers of articles concerning the Partington and modified Puestow's procedure were 6 to 9, being constant from 1991 to 2009, while those concerning Beger and Frey procedures significantly increased after 1996 compared to those during the period of 1991 to 1995 (Fig. 1). With the relatively rapid adoption of the these two procedures, especially in Europe, as shown in Fig. 1, it seems that the Partington procedure for chronic pancreatitis has become a thing of the past. In this review, the Partington procedure was re-evaluated with regard to the historical aspects and the present status.

History of LPJ

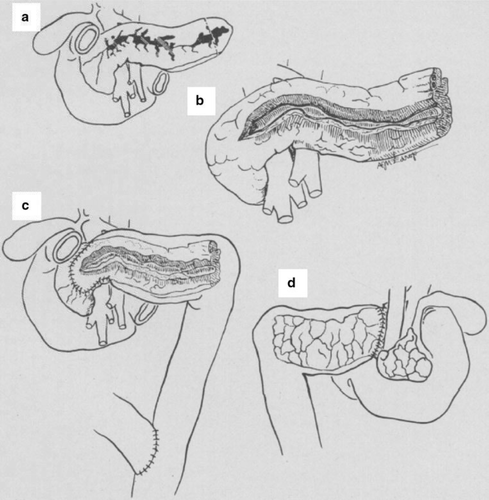

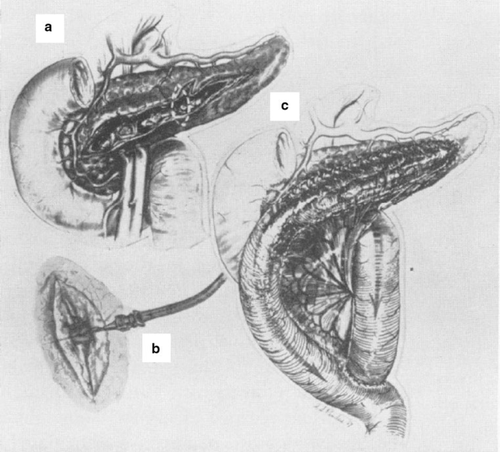

In 1958, Puestow and Gillesby [7] introduced a novel approach, LPJ, decompressing nearly the entire length of the pancreatic duct. Puestow's description of LPJ is in part different from the current modified version used by surgeons now. The original description recommended removal of the spleen following initial exposure of the pancreatic tail, because his rationale was based on the difficulty of separating the splenic vessels from the associated inflammation in the pancreatic tail. Exposure of the duct was simply to incise the tail of the pancreas transversely until pancreatic fluid under pressure was released from the transected main duct. After removing the spleen and amputating the tail of the pancreas, the gland was mobilized as far as the superior mesenteric vessels. Namely, the original Puestow procedure was a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy followed by longitudinal opening of the pancreatic duct with insertion of the pancreas into a Roux-en-Y limb of jejunostomy (Fig. 2).

In 1960, Partington and Rochelle [8] introduced a modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. They reported side-to-side anastomosis of a longitudinal opening in the jejunum to the longitudinally opened pancreatic duct (Fig. 3). The length of the pancreatic duct opening was from the distal most portion of the tail to the site somewhat to the right of the mesenteric vessels. By doing this, they avoided resecting the distal pancreas and spleen and were able to achieve extended drainage of the pancreatic duct. Their modification of Peustow's procedure became the standard drainage procedure for chronic pancreatitis.

Outcome of the Partington procedure

The main advantage of the Partington procedure is the maintenance of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine function. In the past, the demonstration of a small but significant loss of pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function after pancreatic drainage procedures was mostly obtained from retrospective, nonstandardized studies. Two prospective, standardized studies [9, 10] showed that successful pancreatic duct internal drainage actually postpones the appearance of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency by this procedure.

The results of the Partington procedure in patients with chronic pancreatitis are summarized in Table 1 [3, 11-20]. This procedure relieves chronic abdominal pain in 66–91% of patients with a mean follow-up of 3.5–9.1 years. Morbidity and mortality rates are generally low, averaging 20 and 2%, respectively [11, 12]. Despite these encouraging results, long-term follow-up of patients after this procedure revealed that up to 50% of patients developed recurrent symptoms, and 10–35% failed to obtain pain relief [11, 21]. As a consequence of the multiple strictures and dilatations of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis, about 30% of the patients with a dilated Wirsung duct will not present pain relief after a successfully performed Partington procedure in the long-term follow-up [22]. This occurs because some parts of the obstructed ducts, often containing stone material, mainly at the head of the pancreas, are left undrained [23]. It is important to note that the Partington procedure is generally used for inflammatory disease left of the gastroduodenal artery and is specifically not used as the procedure of choice for inflammatory disease of the head of the pancreas [24].

| References | Year | No. of patients | Operative mortality (%) | Mean follow-up (years) | Pan relief (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nealon et al. [13] | 2001 | 124 | 0 | 6.5 | 86 |

| Delcore et al. [14] | 1994 | 28 | – | 3.5 | 86 |

| Greenlee et al. [15] | 1990 | 50 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 82 |

| Bradley [16] | 1987 | 48 | 0 | 5.8 | 66 |

| Sato et al. [17] | 1986 | 43 | 0 | 9.1 | 91 |

| Holmberg et al. [18] | 1985 | 51 | 0 | 8.2 | 72 |

| Warshaw [19] | 1985 | 36a | 3.0 | 3.6 | 83 |

| Sarles et al. [20] | 1982 | 69 | 4.2 | 5 | 85 |

- a Pancreaticojejunostomy combined with choledochoenterostomy and gastrojejunostomy

Remedial operations after a failed Partington procedure include re-drainage procedures and resection. Re-drainage may include extension of the length of pancreatic duct incision and drainage with the same or a new limb of the jejunum, or drainage of the biliary tree with choledochojejunostomy. Resection most commonly involves a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy or standard pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Extended LPJ and combination of resection and LPJ

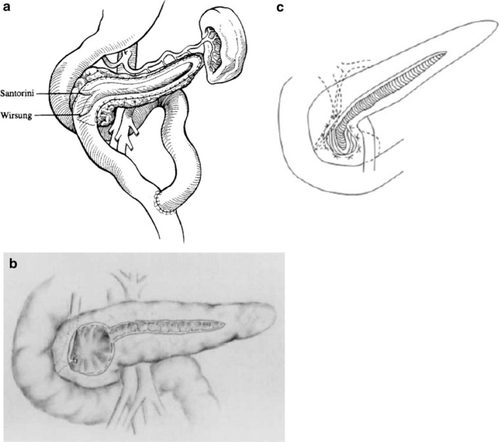

To overcome the pitfall that the obstructed ducts at the head of the pancreas are left undrained after the Partington procedure, Aranha et al. [25] recommend extended LPJ with unroofing of the pancreatic duct to within 1–2 cm of the splenic hilum and within 1 cm of the duodenum for the purpose of decompression of all of the main pancreatic duct including the ducts of Wirsung and Santorini (Fig. 4a). They furthermore insist that it is also important to open and drain the uncinate process and assure full removal of pancreatic stones in addition to fully decompressing the main pancreatic duct.

LPJ has been combined with local resection of the head of the pancreas in some patients to achieve the presumed benefits of both resectional and decompressive procedures in removing the affected tissue in the head of the pancreas while draining the dilated duct. A diffusely enlarged pancreatic head may prevent adequate anterior ductal drainage in the part of the gland that is most necessary to drain. To avoid this problem, the Frey procedure was developed [6]. The Frey procedure consists of LPJ with coring out of the pancreatic head to decompress not only Wirsung's duct, but also the nested ductules in the pancreatic head. The original Frey procedure involves coring out the anterior and posterior parenchyma of the main pancreatic duct. This procedure emphasized resection of the parenchyma as much as possible (Fig. 4b).

Recently, however, a modified Frey procedure to minimize the resection of the pancreatic head has been developed by Sakata et al. [26]. The minimum Frey procedure (Fig. 4c) focuses on the decompression effect achieved by opening the anterior surface of the main pancreatic duct with minimal parenchyma resection (small spindle-shaped resection of the anterior wall of the pancreatic head) to preserve the parenchyma as much as possible and avoid injury to the common bile duct or portal vein. Their comparative study of the Frey and minimum Frey procedures revealed the same effectiveness of the two procedures in terms of pain relief, nutritional status, endocrine function and safety. They concluded that the minimum Frey procedure can be considered as the standard procedure for preserving the parenchyma and for avoiding injury to the common bile duct and portal vein in most patients with chronic pancreatitis, because chronic pancreatitis patients in Japan rarely have a large inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head at the time of operation. The minimum Frey procedure resembles the extended LPJ by Aranha et al. [25] (Fig. 4a, c). It is of interest that the inflammatory pancreatic head mass is not a universal finding of chronic pancreatitis. A recent collaborative study performed at the Massachusetts General Hospital (USA) and the University of Freiburg (Germany) has found that the median diameter of the pancreatic head in chronic pancreatitis is 2.6 cm among American patients and 4.5 cm among German patients (P < 0.001) [27]. Therefore, the minimum Frey procedure or extended LPJ is justified for most chronic pancreatitis patients in countries like Japan and the USA where the inflammatory head mass is rarely encountered.

Partington procedure—present status and future considerations

In recent years, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections such as the Beger and Frey procedures have been adopted in European countries where the patients with head-dominant chronic pancreatitis are frequently encountered, while in the USA doctors have been slow to adopt these procedures. In 2007, Varghese and Bell [28] reported the results of the USA national survey on duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resections. The web-based national survey was completed by 64 of 118 members of the Pancreas Club. Of the 59 surgeons who perform operations for chronic pancreatitis, 34 had performed a duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection at least once. Only 23 US surgeons continue to perform these procedures. Most surgeons who are not performing these procedures responded that, despite the published literature, existing procedures such as the Whipple and Partington procedures were better procedures.

To obtain the information about how often the Partington procedure has been adopted in recent years as surgical management of chronic pancreatitis in the USA, I conducted a PubMed search from January 2001 to June 2009, and two articles were found. According to Nealon et al. [13], 185 patients underwent 199 surgical procedures from 1985 to 1999: 124 Partington procedures, 29 distal pancreatectomies and 46 pancreatic head resections such as pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (14 performed after failure of the Partington procedure). Schnelldorfer et al. [29] reviewed the records of 372 consecutive patients who underwent operations for chronic pancreatitis from 1995 to 2003: LPJ in 184 patients including the Partington procedure (n = 147) and Frey procedure (n = 37), pancreaticoduodenectomy in 97 patients including the Whipple procedure (n = 69) and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 28), and distal pancreatectomy in 91 patients. The Partington procedure is still the most commonly used type of operation in the USA.

As most surgeons point out, the Partington procedure is simple, is safe because of avoiding dissection around the head of the pancreas and is almost as effective in the improvement of pain symptoms. Because it is a relatively easy technique, this procedure has been tried and successfully performed laparoscopically for patients with a dilated main pancreatic duct of more than 10 mm [30, 31]. A consensus statement by the American Gastroenterological Association following review of studies evaluating the Partington procedure for chronic pancreatitis revealed that the morbidity and mortality ranged from 0 to 5%, 80% of the patients had short-term improvement of pain, and 60–70% achieved continued pain relief at 2 years [24]. In a long-term follow-up, however, we should note that about 30% of patients do not benefit from this procedure as a consequence of recurrent pancreatitis in the pancreatic head due to undrained Wirsung and/or Santorini ducts. It is very important to note that the Partington procedure is used for inflammatory disease left of the gastroduodenal artery and specifically not used as the procedure of choice for inflammatory disease of the head of the pancreas. For the inflammatory pancreatic head mass, extended drainage procedures such as the original Frey procedure [6], minimum Frey procedure [26] and extended LPJ [3, 25] should be employed.

Recent randomized controlled study on endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis has revealed that surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct is more effective than endoscopic treatment in patients with obstruction of the pancreatic duct due to chronic pancreatitis [32]. In this study, eligibility criteria included symptomatic patients with a distal obstruction of the pancreatic duct but without an inflammatory pancreatic head mass, and surgical drainage was performed by the Partington procedure. As for the method of the surgical drainage in detail, the pancreatic duct was incised over the full length up to 2 cm from the ampulla, and when retrieval of concretions from the head area required further opening of the duct toward the ampulla, a limited wedge resection of pancreatic tissue was performed.

For patients with a dilated main pancreatic duct but without an inflammatory pancreatic head mass, the Partington procedure is still the surgical procedure of choice, since it is technically simple to perform with a minimum of morbidity and mortality, providing pain relief in a high percentage of patients and preserving pancreatic endocrine and exocrine function. Because it is a relatively simple technique, the laparoscopic approach will be justified as a treatment of appropriate patients with chronic pancreatitis in the near future.