Sensitivity of the familial high-risk approach for the prediction of future psychosis: a total population study

Abstract

Children who have a parent with a psychotic disorder present an increased risk of developing psychosis. It is unclear to date, however, what proportion of all psychosis cases in the population are captured by a familial high-risk for psychosis (FHR-P) approach. This is essential information for prevention research and health service planning, as it tells us the total proportion of psychosis cases that this high-risk approach would prevent if an effective intervention were developed. Through a prospective cohort study including all individuals born in Finland between January 1, 1987 and December 31, 1992, we examined the absolute risk and total proportion of psychosis cases captured by FHR-P and by a transdiagnostic familial risk approach (TDFR-P) based on parental inpatient hospitalization for any mental disorder. Outcomes of non-affective psychosis (ICD-10: F20-F29) and schizophrenia (ICD-10: F20) were identified in the index children up to December 31, 2016. Of the index children (N=368,937), 1.5% (N=5,544) met FHR-P criteria and 10.3% (N=38,040) met TDFR-P criteria. By the study endpoint, 1.9% (N=6,966) of the index children had been diagnosed with non-affective psychosis and 0.5% (N=1,846) with schizophrenia. In terms of sensitivity, of all non-affective psychosis cases in the index children, 5.2% (N=355) were captured by FHR-P and 20.6% (N=1,413) by TDFR-P approaches. The absolute risk of non-affective psychosis was 6.4% in those with FHR-P, and 3.7% in those with TDFR-P. There was notable variation in the sensitivity and total proportion of FHR-P and TDFR-P cases captured based on the age at which FHR-P/TDFR-P were determined. The absolute risk for psychosis, however, was relatively time invariant. These metrics are essential to inform intervention strategies for psychosis risk requiring pragmatic decision-making.

A major focus of psychiatric research in the past quarter century has been the prediction and prevention of severe mental illness, in particular psychotic disorders1-3. In order to achieve psychosis prediction (and, ultimately, prevention), researchers have pursued a number of “high-risk” approaches, seeking to identify individuals at elevated risk of developing psychotic disorders4-7.

The familial high-risk approach to psychosis (FHR-P) is one of the most widely used “high-risk” strategies in psychiatric research1. This approach involves identifying individuals at elevated risk of psychosis based on having family members (especially first-degree relatives) with a history of psychotic disorder. Several studies have demonstrated that individuals who have a first-degree relative with a history of psychotic disorder present an increased risk of going on to develop psychosis8-16, identifying the FHR-P approach as a potential strategy for psychosis prediction and prevention. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis published in this journal8 reported that 8% of the offspring of parents who had one or more psychotic episodes went on to themselves develop psychosis.

While it is established that the offspring of individuals with a history of psychotic disorder have an increased risk of psychosis, it is unclear to date what proportion of all psychosis cases in the population are captured by the FHR-P approach, i.e. the sensitivity of this approach to capture future cases. This is essential information for prevention research and health service planning, as it tells us the upper limit of psychosis cases that could be prevented if we were to identify an effective preventive intervention17, 18. We therefore aimed to assess, using a prospective design, both the absolute risk of psychosis in individuals having one or both parents with a history of psychotic disorder, and the sensitivity of the FHR-P approach in terms of the total proportion of all future psychosis cases that it captures.

Given increasing evidence of transdiagnostic risk for psychosis, we also aimed to apply these questions to a transdiagnostic familial risk approach (TDFR-P)8, 19, 20. That is, we evaluated the risk of psychosis in individuals with a parent who had received inpatient treatment for any mental disorder (not just for psychotic disorders), and established the sensitivity of the TDFR-P approach to capturing future cases of psychosis.

We used total population health care register data on all people born in Finland from 1987 to 1992 in order to calculate the following: a) the absolute risk of psychosis in individuals when one or both parents had a history of psychotic disorder (FHR-P approach); b) the proportion of all cases of psychosis in the population captured by the FHR-P approach; c) the absolute risk of psychosis in individuals when one or both parents had a history of inpatient treatment for any mental disorder (not limited to psychosis, the TDFR-P approach); and d) the proportion of all cases of psychosis in the population captured by the TDFR-P approach.

We also conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, absolute risk and sensitivity for capturing future psychosis may vary depending on the age at which one determines FHR-P or TDFR-P status. Thus, we investigated the effect of various cut-off ages on the absolute risk and sensitivity for capturing future cases of psychosis in the population. Second, we examined the separate contributions of maternal history, paternal history and a history on both sides of the family to the absolute risk and sensitivity for psychosis.

METHODS

National register data

Finnish national register data were used to identify the population of interest. We linked data from the Medical Birth Register, the Care Register for Health Care, Statistics Finland (for death records), and Digital and Population Data Services (for emigration records).

The Care Register for Health Care provides information on all inpatient visits within a person's lifetime (both parents and offspring) and all outpatient visits to a secondary level health care from the year 1998 to present. Information on diagnosis (ICD-8: 1965-1986, ICD-9: 1987-1995, and ICD-10: 1996-2016), admission and discharge dates, and whether it was an inpatient or outpatient visit are recorded for all observations. The register-based data have been shown to have good diagnostic validity, especially for psychotic disorders21, 22.

Population

All individuals born in Finland between 1987 and 1992 (N=384,551) were identified using the Medical Birth Register. Individuals who had died or emigrated prior to 2016 (N=11,957) were excluded, as were individuals for whom data linkage was unavailable in both parents (N=3,657). Reasons for lack of data linkage availability include parent not registered in the medical birth register or requested register removal. The final sample included all individuals born in Finland between 1987 and 1992 and for whom parental data linkage was possible, herein referred to as index children.

Exposure

FHR-P was defined as having at least one parent with a recorded history of non-affective psychotic disorder. TDFR-P was defined as having at least one parent with a recorded history of one or more inpatient psychiatric admissions (for any reason) up to the index child's 13th birthday.

The Care Register for Health Care was used to identify the records of mothers and fathers of the index children within the sample. For harmonization and consistency across the databases (1965-2016), both FHR-P and TDFR-P were based on primary diagnosis within inpatient records (non-affective psychotic disorder in the case of FHR-P, and psychiatric inpatient admission for any reason in the case of TDFR-P).

Harmonization of the ICD codes across versions 8, 9 and 10 was carried out according to Lahti et al23 (see also supplementary information). All maternal and paternal records were identified separately and compiled into FHR variables.

Sensitivity and absolute risk are metrics which may vary depending on the time point that is set for capturing parental diagnoses (for example, taking parental psychiatric history by the birth of the index child versus at a later stage in the child's development). For our primary analyses, we set this threshold as the 13th birthday of the index child. For completeness and comparison, however, we also calculated the equivalent figures when the threshold was set as the index child's birth, 5th birthday, 18th birthday, and study endpoint.

Outcome

Non-affective psychosis in the index children was defined by the ICD-10 diagnostic code F20.x, F23.x, F28, F29, F22.x, F25.x or F24. This diagnosis was identified using inpatient or outpatient records. Schizophrenia was defined as a recording of ICD-10 F20.x diagnosis.

Demographic variables

We report the sex observed at birth, and mother's and father's highest attained education at the time the index child was born. Low corresponds to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) classes 0-2, intermediate to ISCED classes 3-5, and high to ISCED classes 6-824.

Analyses

We report the incidence of FHR-P and TDFR-P, as well as the incidence of non-affective psychosis and schizophrenia specifically, in the index children by the end of follow-up (index child age range: 25-29 years). Demographic descriptive statistics are provided for the overall sample and for those with FHR-P and TDFR-P.

We report the sensitivity, absolute risk and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for both non-affective psychosis and schizophrenia. HRs were calculated using a Cox proportional hazard model, with date of entry set as the index child's 13th birthday, and date of exit specified as exposure to the outcome, death, emigration, or administrate censoring on December 31, 2016.

We examined the change in sensitivity and absolute risk across the different index child age-points when familial risk was determined. We separately examined the contributions of maternal and paternal diagnoses to sensitivity and absolute risk. We examined the duration of time between parental psychosis/inpatient admission and the index child's psychosis diagnosis. Since there was a maximum of five-year difference in the duration of follow-up between index children born in different years, and longer follow-up will result in higher incidence of psychosis in the index children, we conducted an analysis restricted to just those born in 1987 (i.e., with the longest follow-up), examining the sensitivity and absolute risk of both familial risk approaches.

RESULTS

Incidence data and demographic variables

After excluding those who had died or emigrated prior to 2016, or for whom data linkage was unavailable in both parents, 368,937 children born in Finland between 1987 and 1992 were included in our analyses (“index children”). In total, 1.5% (N=5,544) of these children had at least one parent with an inpatient psychiatric admission for a psychotic disorder, and 10.3% (N=38,040) of them had at least one parent with an inpatient psychiatric admission for any reason prior to the child's 13th birthday. Of the index children, 1.9% (N=6,966) had been diagnosed with non-affective psychosis and 0.5% (N=1,846) had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by the study endpoint.

The proportion of males in FHR-P (51.0%, N=2,827) and TDFR-P (51.3%, N=19,524) groups was similar as in the total population (51.2%, N=188,991). By the time of the child's birth, there were significant differences between FHR and non-FHR groups in maternal (FHR-P: X2=349.47, p<0.001; TDFR-P: X2=5.1e3, p<0.001) and paternal (FHR-P: X2=398.64, p<0.001; TDFR-P: X2=4.8e3, p<0.001) education level, as the proportion of mothers and fathers with low education was higher in FHR-P (29.6% and 31.9%) and TDFR-P (33.5% and 37.2%) than in non-FHR (20.1% and 23.9%) groups, while the proportion of mothers and fathers with tertiary education was lower in FHR-P (7.7% and 8.7%) and TDFR-P (6.5% and 7.3%) than in non-FHR (11.3% and 14.2%) groups.

Sensitivity and absolute risk data

Of all non-affective psychosis cases diagnosed after the index child's 13th birthday, 5.2% (95% CI: 4.7-5.7, N=355) were captured by the FHR-P approach. Of all schizophrenia cases diagnosed after the index child's 13th birthday, 6.2% (95% CI: 5.2-7.4, N=114) were captured by the FHR-P approach (see Table 1).

| Risk system stratified by age limit | Incidence of FHR, % (N) | Non-affective psychosis | Schizophrenia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute risk | Sensitivity | Absolute risk | Sensitivity | ||

| FHR-P | |||||

| Birth | 0.7 (2,397) | 7.3% | 2.5% | 1.9% | 2.5% |

| Age 5 | 0.9 (3,130) | 7.5% | 3.4% | 2.3% | 4.0% |

| Age 13 | 1.5 (5,544) | 6.4% | 5.2% | 2.1% | 6.2% |

| Age 18 | 1.9 (6,872) | 4.6% | 5.8% | 1.8% | 7.4% |

| Ever | 2.2 (8,273) | 6.1% | 7.2% | 2.1% | 9.3% |

| TDFR-P | |||||

| Birth | 4.7 (17,573) | 4.3% | 10.8% | 1.2% | 11.3% |

| Age 5 | 6.6 (24,574) | 4.2% | 14.8% | 1.2% | 16.0% |

| Age 13 | 10.3 (38,040) | 3.7% | 20.6% | 1.0% | 21.3% |

| Age 18 | 12.3 (45,982) | 2.7% | 23.0% | 0.9% | 24.5% |

| Ever | 15.2 (56,636) | 3.5% | 28.7% | 1.0% | 29.3% |

- The bold prints indicate that for primary analyses the threshold was set as the 13th birthday of the index child

Of all non-affective psychosis cases diagnosed after the index child's 13th birthday, 20.6% (95% CI: 19.7-21.6, N=1,413) were captured by the TDFR-P approach. Of all schizophrenia cases diagnosed after the index child's 13th birthday, 21.3% (95% CI: 19.5-23.3, N=391) were captured by the TDFR-P approach.

The absolute risk of non-affective psychosis in FHR-P children was 6.4% (95% CI: 5.8-7.1, N=355; HR=3.7, 95% CI: 3.3-4.1). The absolute risk of schizophrenia in FHR-P children was 2.1% (95% CI: 1.7-2.5, N=114; HR=4.4, 95% CI: 3.6-5.3).

The absolute risk of non-affective psychosis in TDFR-P children was 3.7% (95% CI: 3.5-3.9, N=1,413; HR=2.3, 95% CI: 2.2-2.4). The absolute risk of schizophrenia in TDFR-P children was 1.0% (95% CI: 0.9-1.1, N=391; HR=2.4, 95% CI: 2.1-2.7).

Further analyses

Within our main analysis, we included parental diagnoses until the index child's 13th birthday, which resulted in 1.5% of the population meeting FHR-P criteria. By the end of the study follow-up period, however, 2.2% (N=8,273) of the index children met FHR-P criteria. The absolute risk and sensitivity of the FHR-P at selective ages of the index children are reported in Table 1. Depending upon the age at which FHR-P was determined, the absolute risk of non-affective psychosis varied from 4.6% to 7.5%, and the sensitivity ranged from 2.5% to 7.2%.

Compared with an age 13 years cut-off, where 10.3% of the index children were in the TDFR-P group, 15.2% (N=56,636) of the index children met TDFR-P criteria by the end of the follow-up. Depending upon the age at which TDFR-P was determined, the absolute risk of psychosis varied from 2.7% to 4.3%, and the sensitivity ranged from 10.8% to 28.7% (see Table 1).

The maternal and paternal contributions to sensitivity and absolute risk are displayed in Table 2. Broadly, in FHR-P for non-affective psychosis, mothers and fathers had equivalent contributions to both sensitivity and absolute risk. Fathers had a higher incidence of inpatient psychiatric admission (TDFR-P), and thus contributed slightly more to the sensitivity in this approach. The absolute risk of non-affective psychosis was 16.7% for individuals in whom both parents had a history of psychosis and 6.9% for individuals in whom both parents had a history of inpatient psychiatric admission (for any reason).

| FHR-P | TDFR-P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence, % (N) | Absolute risk | Sensitivity | Incidence, % (N) | Absolute risk | Sensitivity | |

| Non-affective psychosis in index children | ||||||

| Mother | 0.8 (3,038) | 7.1% | 3.1% | 4.2 (15,532) | 4.4% | 10.0% |

| Father | 0.7 (2,608) | 6.0% | 2.3% | 6.8 (25,248) | 3.6% | 13.3% |

| Both | 0.03 (102) | 16.7% | 0.3% | 0.7 (2,740) | 6.9% | 2.7% |

| Schizophrenia in index children | ||||||

| Mother | 0.8 (3,038) | 2.4% | 3.9% | 4.2 (15,532) | 1.3% | 10.8% |

| Father | 0.7 (2,608) | 2.0% | 2.8% | 6.8 (25,248) | 1.0% | 14.0% |

| Both | 0.03 (102) | 9.8% | 0.6% | 0.7 (2,740) | 2.3% | 3.5% |

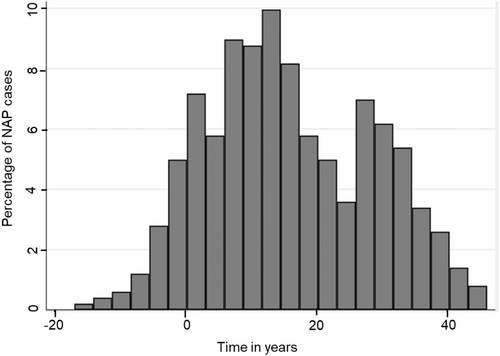

For individuals who developed non-affective psychosis, the median number of years between parental first psychosis diagnosis and the index child diagnosis was 14.1 years (interquartile range, IQR: 6.3-26.7, see Figure 1). For individuals who developed schizophrenia, the median number of years between parental first inpatient admission and the index child diagnosis was 13.3 years (IQR: 5.8-23.0, see supplementary information).

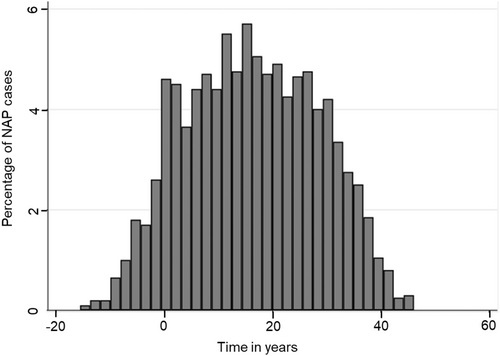

For individuals who developed non-affective psychosis, the median number of years between parental first inpatient admission and the index child diagnosis was 16.1 years (IQR: 6.5-26.0, see Figure 2). For individuals who developed schizophrenia, the median number of years between parental first inpatient admission and the index child diagnosis was 17.8 years (IQR: 7.9-27.4, see supplementary information).

Restricting analyses to those who had the longest follow-up period (individuals born in 1987 only) had little impact on the sensitivity and absolute risk of either approach. Of all non-affective psychosis diagnoses in the index children, 5.3% (95% CI: 4.0-6.7, N=64) were from FHR-P. Of all schizophrenia diagnoses in the index children, 4.3% (95% CI: 4.5-6.9, N=15) were from FHR-P. Of all non-affective psychosis diagnoses in the index children, 20.4% (95% CI: 18.1-22.8, N=247) were from TDFR-P. Of all schizophrenia diagnoses in the index children, 23.3% (95% CI: 19.0-28.1, N=82) were from TDFR-P (see also supplementary information).

DISCUSSION

Using total population health care register data, we identified the total proportion of future psychosis cases captured by the FHR-P approach. Following the total population born in the years 1987-1992 from age 13 to 29 years, we found that 5.2% of all psychosis cases in the index children were captured by the approach. This is the upper limit of psychosis cases that could be prevented using the approach if we had an effective preventive intervention.

We also identified the total proportion of future psychosis cases captured by taking a transdiagnostic approach to familial risk (i.e., parents with a history of psychiatric admission for any reason). In total, 20.6% of all psychosis cases were captured by this approach.

The sensitivity of the FHR-P approach for capturing future psychosis was similar to recent UK findings on the sensitivity of the clinical high risk (CHR) approach. Researchers in South London mental health services found that their CHR clinics captured 4.1% of future psychosis cases25. FHR-P and TDFR-P status, in contrast to the CHR approach, can be identified based on routine administrative health care data. Thus, unlike the CHR approach, the identification of risk using the FHR approach is not inherently associated with any additional costs or other types of burden for the clinician or the individual.

We also calculated the absolute risk of psychosis associated with FHR-P and TDFR-P status. We found that 6.4% of all children who had a parent with psychosis went on to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder by age 25-29 years. The equivalent figure for the TDFR-P approach was 3.7%. In contrast to time-varying effects on sensitivity, the age at which familial risk was determined had little effect on absolute risk.

The absolute risk of psychosis associated with both FHR approaches was lower than the risk of psychosis typically reported for the CHR approach. A systematic review of studies of children and adolescents diagnosed with a CHR syndrome found that 16% went on to be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder at follow-ups of 5 years or more26. Within samples of adults and young people, the cumulative transition risk was 28% at over 4 years27. The absolute risk associated with meeting FHR-P and TDFR-P criteria suggests that, similar to the CHR approach5, additional factors are needed to stratify risk among the FHR groups.

We found little difference in the contributions of maternal versus paternal psychosis to the absolute risk and sensitivity for non-affective psychosis or schizophrenia in the index children. The absolute risk for non-affective psychosis and schizophrenia was notably higher if both parents had a history of psychosis, at 16.7%, though this event was rare. There was also little difference in the relationship between maternal versus paternal history of psychiatric admission and the absolute risk of psychosis or schizophrenia. Paternal psychiatric history, however, was more sensitive to capturing future offspring psychosis than maternal psychiatric history. This was attributable to the higher incidence of psychiatric inpatient admission in fathers.

Finally, we observed significant differences in the proportion of parent and index children cases identified when different age cut-offs were applied to the FHR systems. This clearly demonstrates that the age cut-offs for FHR systems need careful and pragmatic consideration to ensure that they: a) capture enough of the total cases of parents who qualify over their lifetime (FHR-P or TDFR-P); b) capture enough of the index children who develop psychosis; and c) allow a sufficient window for an intervention to occur between parent entering the FHR system and index child's diagnosis.

In order to prevent unnecessary stigmatization and fear, we recommend that professionals applying FHR-P approaches are explicit about the absolute risk of psychosis. Although the risk is elevated from a relative perspective, just 6.4% of all FHR-P individuals had been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder by the end of follow-up. This means that more than 93% did not develop psychosis. For individuals with transdiagnostic familial risk based on a parental history of inpatient psychiatric admission, more than 96% did not develop psychosis by the end of follow-up. Moreover, only a minority of psychosis cases arose in individuals at familial risk. This information should prevent any sense of fatalism associated with familial risk for psychosis.

This study used national register data covering the entire population of Finland born from 1987 to 1992. It had parental data linkage for both mother and father histories, with only a small proportion of cases for whom linkage was unavailable (<2%). In countries with developed-registers, these risk systems are already recorded as part of administrative health data and require no additional cost to operationalize. This weighs favorably against symptom-based risk indicators, which require lengthy and costly assessments that need to be conducted by trained medical professionals and require patient input and resourcing.

Familial risk was identified based on psychiatric inpatient records for the parents of index children. The validity of these records, specifically for psychosis, have been previously examined, with true positive accuracy ranging from 75 to 93%21, 22, 28. Of course, not all parents with mental disorders may have been hospitalized, which has likely generated a downward bias in the estimates of proportions of affected parents and offspring.

In terms of transdiagnostic familial risk, we had data on inpatient, but not outpatient, psychiatric admissions for the parents. We would hypothesize that, if we were to extend the study to include outpatient psychiatric care, this would increase the sensitivity to capture risk for future psychosis, but at the expense of a reduced absolute risk. It was not possible to test this in the current study, given the limited period for which outpatient registers have existed. However, as the duration of time for which it is possible to follow individuals in the register naturally increases over time, it may become possible to test this in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

We identified, for the first time, the sensitivity of the FHR-P approach and a novel transdiagnostic familial risk approach for capturing psychosis risk. In total, 5.2% and 20.6% of future psychosis cases were captured, respectively, by the FHR-P and TDFR-P approaches. The sensitivity of these approaches varied according to the age at which familial risk was determined. Absolute risk, on the other hand, was relatively invariant regardless of the age at which familial risk was determined. Additional factors, beyond familial risk, will be necessary to stratify risk for psychosis within these populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by awards to I. Kelleher from the Health Research Board (ECSA-2020-005), the Academy of Medical Sciences (APR8\1005), and the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Supplementary information on this study is available at https://osf.io/my523/?view_only=e394a34edb9a4215ad8af22e74c599e0.