The definition of treatment resistance in anxiety disorders: a Delphi method-based consensus guideline

Abstract

Anxiety disorders are very prevalent and often persistent mental disorders, with a considerable rate of treatment resistance which requires regulatory clinical trials of innovative therapeutic interventions. However, an explicit definition of treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (TR-AD) informing such trials is currently lacking. We used a Delphi method-based consensus approach to provide internationally agreed, consistent and clinically useful operational criteria for TR-AD in adults. Following a summary of the current state of knowledge based on international guidelines and an available systematic review, a survey of free-text responses to a 29-item questionnaire on relevant aspects of TR-AD, and an online consensus meeting, a panel of 36 multidisciplinary international experts and stakeholders voted anonymously on written statements in three survey rounds. Consensus was defined as ≥75% of the panel agreeing with a statement. The panel agreed on a set of 14 recommendations for the definition of TR-AD, providing detailed operational criteria for resistance to pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic treatment, as well as a potential staging model. The panel also evaluated further aspects regarding epidemiological subgroups, comorbidities and biographical factors, the terminology of TR-AD vs. “difficult-to-treat” anxiety disorders, preferences and attitudes of persons with these disorders, and future research directions. This Delphi method-based consensus on operational criteria for TR-AD is expected to serve as a systematic, consistent and practical clinical guideline to aid in designing future mechanistic studies and facilitate clinical trials for regulatory purposes. This effort could ultimately lead to the development of more effective evidence-based stepped-care treatment algorithms for patients with anxiety disorders.

Anxiety disorders – including specific phobias, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), as well as separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism1 – represent the most common mental disorders, with an estimated combined 12-month prevalence of 10-14%2-4. They confer a substantial socioeconomic burden5-7 and often take a debilitating course, with a high proportion of cases having only intermittent recovery (32.1%) or consistent chronicity (8.6%) at 9-year follow-up8. Accordingly, they rank sixth among all disorders regarding years lived with disability (YLDs)9, and seventh in the group of 15-24 year olds and 15th among 25-49 year olds in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)10.

One factor contributing to the chronicity of anxiety disorders is the clinical challenge of treatment resistance, particularly in panic disorder/agoraphobia, GAD, and social anxiety disorder11-14. While effective pharmacological and psychotherapeutic options are available for these disorders as first-line treatments endorsed by clinical guidelines15 – i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) – only 50 to 67% of patients show an adequate clinical response after the first treatment trial16-21. There is, therefore, a pressing need for clinical trials probing novel pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions specifically for patients with treatment-resistant anxiety disorders (TR-AD)22, and for studies exploring predictive markers and mechanistic underpinnings of treatment resistance in anxiety disorders23-25.

A prerequisite for conducting these clinical trials and mechanistic studies is an international consensus on the definition of TR-AD, which is currently lacking17, 26. International guidelines focusing on anxiety disorders do not provide explicit criteria aiding in the identification or treatment of patients with TR-AD15, 27-50, with only two exceptions. First, the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anxiety Disorders51 suggest that patients who “do not respond to first- or second-line agents” (in panic disorder), who “do not respond to several medication trials and/or CBT” (in social anxiety disorder), or who “do not respond to multiple courses of therapy” (in GAD) should be considered treatment-refractory. Second, the most recent version of the Australian Therapeutic Guidelines52 states that “non-response to initial pharmacotherapy for GAD, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder in adults and young people is assumed if symptoms persist despite using an effective dose of at least two SSRIs or SNRIs as sequential monotherapy, each for a minimum of 4 weeks (full benefit may take 6 weeks or longer); and discounting alternative reasons for treatment non-response”.

A search of the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) database53 for a core outcome set defining TR-AD yielded no results. Also, the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Depression and Anxiety Working Group54 did not provide an explicit definition of TR-AD. Searching clinicaltrials.gov for ongoing or terminated studies on TR-AD revealed either no or only vague definitions of this condition. Only one terminated study on social anxiety disorder (ID: NCT00182455) used non-response or partial response – i.e., a score >4 on the Clinical Global Impression Scale - Severity (CGI-S) and >40 on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) – to SSRI treatment (14 weeks) to define treatment resistance more precisely.

A narrative review11 suggested to define treatment-resistant panic disorder as the failure to achieve remission – i.e., a post-treatment Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) score ≤7-10, a Sheehan Disability Scale score ≤1 on each item, and a Panic Disorder Severity Scale score ≤3, after at least 6 months of “optimal treatment” (not further specified). A systematic review14 proposed to define treatment-resistant panic disorder as a condition which has not responded to at least two adequate 8-week treatment trials with drugs recognized as effective for that disorder in adequate doses, or to a standard course of CBT14.

The only systematic review available to date55 could not discern a consistent definition in 62 studies investigating treatment resistance in anxiety disorders. In 62.9% of definitions, treatment resistance was already assumed after failure of a single therapeutic trial. Most studies (93%) required pharmacological, and only 29% psychotherapeutic treatment failure. A large proportion of studies (43.5%) did not specify the type of medication, while some studies (24.2%) deemed one trial of SSRI/SNRI treatment necessary. Most studies (54.8%) required a minimal trial duration ranging from 4 weeks to 6 months, with 24.2% of studies applying an 8-week time frame. While some studies (41.9%) provided a non-response criterion (e.g., post-treatment HAM-A score improvement <50%), the definition of “treatment failure” remained unclear in 58.1% of studies. “High post-treatment anxiety severity” was identified as the most common (46.8%) criterion required to define TR-AD across studies. Having summarized these findings, the authors proposed a definition of TR-AD requiring that the severity of anxiety remains above a specified threshold after failure of at least one first-line pharmacological (SSRI, SNRI) and at least one psychological (CBT) treatment trial, delivered according to protocol for at least 8 weeks. “Treatment failure” was suggested to be defined as a pre- to post-treatment difference in HAM-A score of <50%, or a post-treatment Clinical Global Impression Scale - Improvement (CGI-I) score >2.

Against this background, a recent perspective paper56, after identifying treatment resistance in mental health conditions as a pressing issue, stated that “for certain conditions such as mania, anxiety disorders and PTSD, consensus definitions of resistance have yet to be agreed“. In the present study, we used for the first time a Delphi method-based consensus approach in order to provide internationally agreed, consistent and clinically useful operational criteria for TR-AD in adults, particularly for the clinical phenotypes of panic disorder/agoraphobia, GAD, and social anxiety disorder. This operational definition of TR-AD is expected to inform future mechanistic studies as well as clinical trials of both pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies conducted for regulatory purposes, in an effort to develop more targeted and personalized treatment options reducing the individual and collective socioeconomic burden of anxiety disorders.

METHODS

This study was initiated by the Anxiety Disorders Research Network (ADRN), an international collaborative cross-disciplinary research group, with support from the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP). The ADRN presently includes 28 members across 14 countries and has the principal goal of addressing currently unmet needs in anxiety and related disorders.

A subgroup of 15 ADRN members with clinical and/or basic scientific expertise in TR-AD formed the core expert team for the study. A further 18 experts (academics, clinicians, basic scientists) and three key stakeholders (two representatives of regulatory bodies, and a representative from a mutual aid advocacy organization) were selected to form the final panel (see supplementary information).

The Delphi method was considered the most appropriate tool for developing a consensus definition of TR-AD57-60. The method was applied according to the Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi studies (CREDES)61, and following the approach recently used to develop a consensus guideline for the definition of treatment-resistant depression in clinical trials62. The study was registered with the Freiburger Register für Klinische Studien (FRKS) (FRKS004463) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Freiburg (23-1021-S1).

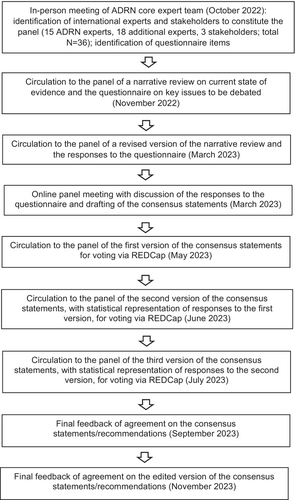

Twenty-nine items were identified for inclusion in an initial questionnaire on TR-AD, based on a review of the literature and an in-person meeting of the ADRN core expert team in October 2022. The questionnaire, along with a narrative review of the current state of the evidence, was sent to the panel in November 2022. Anonymized responses to the questionnaire and a revised version of the narrative review were sent back to the panel and discussed in an online meeting in March 2023, using a nominal group technique to agree on the selection and wording of consensus statements. A resulting set of initially 15 draft consensus statements was subsequently sent out to the panel using the REDCap® online platform. In three a priori defined iterative rounds (in May, June and July 2023), all participants anonymously rated their agreement with each of the individual statements on a labelled, horizontal 9-point Likert scale (a “no answer” option was available) and could comment on or suggest changes to the phrasing or substance of the statements. After each iterative round, participants received feedback in the form of a cumulative statistical representation of the overall panel's response, and had access to anonymized comments by their fellow panelists (see Figure 1 and supplementary information).

Where participants gave a score of 1 to 3 to a statement on the Likert scale, low agreement was assumed. A score of 4 to 6 indicated moderate agreement with a statement. When a statement was scored 7 to 9, it was considered to be agreed upon substantially63. Consensus regarding a statement was considered reached when ≥75% of the panel voted in substantial agreement with it, i.e. gave a score of 7 to 9. This aligns with the development of other core outcome sets64-67, and with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)68. Those who had chosen the “no answer” option were removed from the denominator when ascertaining whether consensus had been reached. Statements reaching less than or only around 75% consensus in iteration rounds 1 and 2 were dropped or amended on the basis of free-text responses provided by the panel and entered as such into voting rounds 2 and 3, respectively (see supplementary information). The 14 final consensus recommendations on TR-AD as emerging from round 3 are summarized in Table 1.

| No. | Statement | Mean score ± SD on 9-point Likert scale | % of agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| General remarks | |||

| 1 | A definition of TR-AD is useful for both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic clinical trials conducted for regulatory purposes. |

8.74±0.58 |

100 |

| 2 | A definition of TR-AD is useful for research, e.g. in the search for disease or treatment response mechanisms and biomarkers. |

8.68±0.60 |

100 |

| Operational definition | |||

| 3 | The definition of treatment failure should ideally, but not necessarily, rest on both observer-rated and self-report scales. |

8.23±0.99 |

90.3 |

| 4 | Treatment failure in anxiety disorders can be operationally defined by the failure to achieve clinically significant reduction in symptom severity from pre- to post-treatment. This can be reflected by a <50% reduction in Hamilton Anxiety Scale score or a <50% reduction in Beck Anxiety Inventory score or a Clinical Global Impression Scale - Improvement >2. |

8.35±0.75 |

96.8 |

| 4a | Optional specific criteria for treatment failure in social anxiety disorder: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS)-SR (self-rating) score reduction <28% or LSAS-CA (clinician-administered) score reduction <29%. |

8.21±1.11 |

89.7 |

| 4b | Optional specific criteria for treatment failure in GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale score <4-point reduction, or Penn State Worry Questionnaire score <9% or <4-point reduction. |

8.03±1.09 |

89.7 |

| 4c | Optional specific criteria for treatment failure in panic disorder/agoraphobia: Panic Disorder Severity Scale score reduction <40% or Panic Agoraphobia Scale score reduction <23%. |

8.03±1.09 |

89.7 |

| 5 | The definition of pharmacological treatment resistance in anxiety disorders should rest on at least two failed trials of pharmacological monotherapy with first-line agents approved for the treatment of anxiety disorders and recommended by guidelines (two different classes, e.g. one SSRI plus one SNRI, clomipramine or pregabalin, in the case of GAD) using at least the minimal approved dose, for the duration of at least 6-8 weeks each, ideally with documented therapy adherence. |

8.50±0.73 |

100 |

| 6 | The definition of psychotherapeutic treatment resistance in anxiety disorders should rest on at least one failed trial of adequately delivered (e.g., qualified therapist) first-line psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with adequate intensity (e.g., a sufficient number of exposure exercises, homework, adherence) and duration (depending on the type of anxiety disorder, e.g., 12-20 weeks in GAD, panic disorder/agoraphobia or social anxiety disorder). |

8.07±1.55 |

96.7 |

| Staging model | |||

| 7 |

A staging model might capture the spectrum of TR-AD with various levels of treatment resistance, comprising: i) failure of either two adequate courses of pharmacotherapy or ≥1 adequate trial of psychotherapy ii) failure of both two adequate courses of pharmacotherapy and ≥1 adequate trial of psychotherapy iii) failure of multiple adequate courses of (poly)pharmacotherapy and multiple adequate trials of psychotherapy (connoting multi-modal TR-AD, MTR-AD). |

8.29±0.82 |

100 |

| Additional aspects | |||

| 8 | Comorbidities with depression, substance abuse or personality disorders should not influence the operational definition of TR-AD, but their presence should be recorded and considered post-hoc. |

8.65±0.61 |

100 |

| 9 | Subgroups of AD (e.g., by sex, age, menopause, peri-partum period) should not influence the operational definition of TR-AD, but should be recorded and considered post-hoc. |

8.61±0.62 |

100 |

| 10 | Specific biographical factors (e.g., life events, history of trauma) should not influence the operational definition of TR-AD, but their presence should be recorded and considered post-hoc. |

8.58±0.67 |

100 |

| 11 | Duration of illness and number of episodes should not influence the operational definition of TR-AD, but they should be recorded post-hoc, considering that TR-AD by definition might entail a longer duration of illness and that delineation of distinct episodes might be difficult. |

8.65±0.61 |

100 |

| 12 | Research into biomarkers and other predictors and mechanisms of TR-AD might be useful in the future. |

8.71±0.59 |

100 |

| 13 | It is essential to be sensitive and not judgmental towards patients suffering from TR-AD, to include their social environment in the diagnostic and therapeutic process where appropriate, and to respect patients’ preferences after they are fully informed about the comparative efficacy of the various treatment modalities based on current official guidelines. |

8.68±0.60 |

100 |

| 14 | In the future, the merits of the term TR-AD in a regulatory context are to be discussed against potential drawbacks, with consideration of a potentially more comprehensive term such as “difficult-to-treat” anxiety disorders, which might be more useful in a clinical context. |

8.32±0.79 |

100 |

- GAD – generalized anxiety disorder

RESULTS

The panel considered an operational definition of TR-AD to be useful for regulatory clinical trials probing pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (as well as neuromodulation or virtual reality techniques, and repurposed options such as ketamine, psilocybin, or 3,4-methylendioxy-N-methylamphetamine, MDMA) (see Table 1, statement 1). This definition will allow to carry out clinical trials with good external validity, ultimately aiming at improving evidence-based treatment algorithms and guidelines in case of treatment non-response or resistance. This was seen as particularly important since patients with TR-AD have so far mostly been excluded from clinical trials conducted for regulatory purposes.

An operational definition of TR-AD was additionally considered to be essential for research on (bio)markers and (bio)mechanisms of treatment non-response or resistance (see Table 1, statement 2).

Operationalization of treatment failure

The panel voted for the definition of response/non-response to ideally but not necessarily rest on both clinician- and self-report scales (see Table 1, statement 3). Some panelists suggested that clinician ratings are probably most apt for pharmacological trials, and self-reports for psychotherapeutic trials. Clinician ratings have been suggested to possibly increase the effect sizes69, 70, but might at the same time be more sensitive to change and can be applied in an adequately blinded way. Self-report ratings are better able to capture the patient's core emotional experience71, 72, quality of life and symptoms affecting broader dimensions of real life, but may be more relevant for the definition of remission than treatment failure. For an international consensus, the recommended scales should be translated, validated and available in as many languages and countries as possible.

The panel agreed on treatment failure in anxiety disorders to be defined as the failure to achieve a clinically significant symptom reduction from pre- to post-treatment, reflected by a <50% reduction in the HAM-A score, or a <50% reduction in the Beck Anxiety Inventory score, or a CGI-I score >2 (see Table 1, statement 4). This was the final consensus, although some panelists suggested to rather use a 25% or 30% reduction cut-off. In general, a percentage reduction to indicate non-response seemed preferable to post-treatment scores alone, since there may be considerable heterogeneity in before-treatment severity scores. It was also noted that operationalization of treatment resistance based on symptom reduction may not sufficiently portray the full picture of how well a patient does in the long term, which might be better reflected by Sheehan Disability Scale scores.

Several additional, but optional, recommendations on how to define treatment failure in regulatory trials concerning specific anxiety disorders were agreed upon by the panel.

For social anxiety disorder, a score reduction of <28% on the LSAS-SR (self-rating) or <29% on the LSAS-CA (clinician-administered) was suggested to indicate treatment failure (see Table 1, statement 4a). Although a LSAS total cut-off score of 30 has been reported to represent the best balance of specificity and sensitivity73, the panel once again agreed that absolute scores do not account for initial disease severity and thus should not be included in definitions of treatment failure.

As optional operational criteria for treatment failure in GAD, the panel agreed on a <4 point reduction on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale score, or a <9% or <4-point reduction on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire score (see Table 1, statement 4b). GAD-7 cut-off scores ≥8 or ≥10 were also discussed, but discarded because absolute scores do not account for initial disease severity. Some panelists argued that the GAD-7 should not be used as the sole measure for treatment failure in GAD, as some studies failed to define a cut-off score with adequately balanced sensitivity and specificity for GAD74-76, or reported that the GAD-7 had good sensitivity and specificity for any anxiety disorders, but low specificity for GAD77.

For treatment failure in panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, the panel recommended optional operational criteria of a <40% score reduction on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale or a <23% score reduction on the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (see Table 1, statement 4c). Criteria of a <50% score reduction on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale or a <50% decrease in the number of panic attacks were discussed, but were not included in the operational definition.

Resistance to pharmacological treatment (pharmacotherapy TR-AD)

For regulatory trials, it might be useful to differentiate between resistance to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. The panel agreed that resistance to pharmacological treatment in anxiety disorders (pharmacotherapy TR-AD) should be defined as at least two separate failed full trials of pharmacological monotherapy with first-line agents approved for those disorders by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or other equivalent regulatory agencies, and recommended by guidelines. These trials should involve two different classes of medications (e.g., one SSRI plus one SNRI, clomipramine or pregabalin in the case of GAD), used for at least 6-8 weeks each at a dose corresponding to at least the minimal approved one, ideally with documented treatment adherence (see Table 1, statement 5).

It was discussed whether failure of a trial with benzodiazepines should be included in the definition of pharmacotherapy TR-AD. It was argued that the majority of guidelines do not recommend benzodiazepines as first-line options for treatment of anxiety disorders. Regarding the definition of how long one trial of pharmacological treatment should last to be able to evaluate its efficacy, time frames spanning 4 to 12 weeks were considered, but the final consensus was for a treatment duration of 6-8 weeks. Monitoring plasma levels to allow for an optimized dosing and the assessment of treatment “pseudo-resistance” due to non-adherence or a rapid metabolizer status was considered desirable, but not feasible in most routine clinical settings. Treatment pseudo-resistance in general, however, should be excluded by taking into account adherence to treatment as well as additional factors such as age and renal/hepatic function.

Resistance to psychotherapy (psychotherapy TR-AD)

The panel agreed that resistance to psychotherapy in anxiety disorders (psychotherapy TR-AD) should be defined as at least one failed trial of an evidence-based, first-line, standardized, ideally manualized psychotherapy, such as CBT. Treatment should be delivered by a qualified psychotherapist with an adequate intensity and duration, ideally including a sufficient number of exposure exercises as well as monitored between-session work (“homework”) and adherence (see Table 1, statement 6).

Depending on the type of anxiety disorder, a range of one session (for specific phobias) to up to 20 weeks (in GAD, panic disorder/agoraphobia or social anxiety disorder) was proposed to constitute an adequate time frame. For the latter conditions, the consensus was for a minimal duration of 12-20 weeks, with a minimum number of 20 sessions. Individual one-to-one sessions seemed preferable, while group or online formats were discussed as potential alternatives.

Staging model and multi-modal treatment resistance (MTR-AD)

The panel additionally proposed a non-dichotomous, escalating staging model of TR-AD, in analogy to those suggested for obsessive-compulsive disorder78 and major depressive disorder79-81 (see Table 1, statement 7). This model – or alternatively a pseudo-linear scale of degree of resistance – would allow clinical trials for regulatory purposes or other studies to describe a particular population on a dimensional spectrum of treatment resistance, ranging from isolated resistance to pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment to composite resistance to several trials of multiple modalities delivered in different episodes of the anxiety disorder. This flexibility is particularly relevant for anxiety disorders, as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy have been considered similarly effective in these disorders, and as resistance to pharmacotherapy does not preclude response to psychotherapy and vice versa, or to a combination of the two modalities. Also, the (bio)mechanisms of treatment resistance to pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy might be partly distinct.

The model proposed by the panel in order to capture the spectrum of levels of treatment resistance in anxiety disorders comprises a first stage of failure of either two adequate courses of pharmacotherapy or at least one adequate trial of psychotherapy; a second stage of failure of both two adequate courses of pharmacotherapy and at least one adequate trial of psychotherapy; and a third stage of failure of multiple adequate courses of (poly)pharmacotherapy and multiple adequate trials of psychotherapy. This last stage connotes multi-modal TR-AD (MTR-AD) (see Table 1, statement 7), which requires an intensified subsequent treatment approach, including referral to secondary or tertiary specialist care. The (bio)mechanisms underlying MTR-AD might be different from those involved in isolated pharmacotherapy TR-AD or psychotherapy TR-AD.

Additional aspects

The panel agreed that comorbidity with other mental disorders – particularly depression, substance use disorders and personality disorders – should not influence the operational definition of TR-AD, but should be recorded and considered post-hoc (see Table 1, statement 8). Furthermore, the identification of sex and age subgroups was not considered necessary for the operational definition of TR-AD, but relevant for post-hoc analyses as well as for differential treatment. For instance, women in the peri- and post-menopausal or in the peri-partum period, children/adolescents, as well as elderly patients with declining renal or hepatic function, might warrant particular attention (see Table 1, statement 9).

Biographical factors such as socioeconomic status, social support, specific life events (e.g., childhood trauma, acute or chronic stress), as well as exposure to novel anxiogenic stimuli or situations during treatment, were considered to possibly influence treatment resistance19, 82, 83. However, for the sake of simplicity and to reflect a naturalistic setting, those factors were suggested by the panel not to be included in the operational definition of TR-AD, but to be recorded, possibly as “specifiers”, monitored and taken into consideration in post-hoc analyses to reduce the study population variability and, in a clinical setting, to be targeted specifically (see Table 1, statement 10).

The panel agreed that duration of (untreated) illness and number of episodes or relapses, while influencing treatment resistance in several patients84-86, should not be included in the definition of TR-AD, but recorded and considered post-hoc (see Table 1, statement 11). It has to be noted that TR-AD usually involves a longer duration of illness, entailing a potential tautology. Additionally, it might be difficult to delineate distinct episodes. While for TR-AD regulatory trials it might be useful to restrict the number of previous failed treatments, in order to increase the likelihood of improvement, the panel agreed not to propose a statement on the maximum number of failed previous treatments. However, it suggested that they should be routinely recorded and considered post- hoc.

TR-AD vs. difficult-to-treat AD

The panel agreed to use the term “treatment-resistant” anxiety disorders (TR-AD), since it is routinely adopted and widely understood in the present regulatory context, and is already established for other disorders in the international nomenclature. However, it acknowledged that “difficult-to-treat” AD could be considered as a potentially more comprehensive term, which might be more useful in a clinical context (see Table 1, statement 14).

The term TR-AD was considered to clearly refer to the disorder and not to the patient as being treatment-resistant, to the existing treatment options being inadequate, to relate to the patient's history and not the future, to be respectful of the patient-clinician relationship, and to allow a precise definition relevant for drug approval and commissioning of services. The alternative term “difficult-to-treat” AD – in analogy to “difficult-to-treat” depression87 – has been suggested to represent a more comprehensive and multi-dimensional concept, to potentially be more apt to inform clinical practice rather than research or regulatory affairs, and to seem less stigmatizing, pessimistic, discouraging or defamatory from a patient's perspective88.

The concept of “difficult-to-treat” AD might furthermore allow for considering intolerance or refusal or contraindication of treatment, and the impact of living conditions, comorbidities and other factors on treatment outcome, rather than just non-response, and does not relate simply to one point in time when TR-AD criteria are met. Some panelists, however, raised concerns that the term “difficult” could inadvertently be taken to refer to the patient, and even reduce hope for future treatments. Also, it could imply that successful treatments should be “easy” and straightforward, while treatment can still be highly effective despite a very complex, atypical or “difficult” clinical presentation or a “difficult” therapeutic process.

In sum, both terms might be needed, with TR-AD constituting a pragmatic nomothetic construct for clinical trials conducted for regulatory purposes, as well as for other research projects, while “difficult-to-treat” AD could represent a more holistic, idiographic concept as well as a “roadmap” for clinicians relevant to effectiveness trials as well as clinical care. However, the boundaries of “difficult-to-treat” AD are uncertain, and an evidence-based taxonomy as well as reliable assessment tools beyond traditional outcome metrics remain to be established for this condition89. Research into this topic has been deemed to be of importance.

Preferences and attitudes of persons with anxiety disorders

In general, labelling a condition as either TR-AD, MTR-AD, “treatment-refractory” AD or “difficult-to-treat” AD might be regarded as stigmatizing. Consequently, it is essential to be sensitive and not judgmental towards persons experiencing treatment resistance, and to ensure respectful language awareness and use (e.g., “patient with TR-AD”, not “TR patient” or “difficult-to-treat patient”). On the other hand, providing an operational definition of TR-AD might in fact relieve patients from the feeling of having failed themselves, and aid in destigmatizing the condition.

It is imperative that persons with anxiety disorders are fully informed about the comparative efficacy of the various treatment modalities based on current official guidelines, and that their preferences are respected. It is to be taken into consideration that certain classes of medication or psychotherapy might be unacceptable or untimely from a patient's point of view, or that certain treatment options might simply not be available or delivered optimally. Additionally, given that many patients with TR-AD have already gone through numerous pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic treatment trials, the definition of TR-AD should not be limited to a relatively short duration of disease or to a maximum number of failed previous trials, as this would discriminate against those patients by excluding them from regulatory trials that may potentially offer more efficacious treatment options.

In future attempts to further refine the definition of TR-AD, the inclusion of questionnaires focusing on self-reported quality of life and level of functioning – for instance, the Sheehan Disability Scale or the Psychosocial fActors Relevant to BrAin DISorders in Europe (PARADISE 24) metric90 – should be considered. Furthermore, “minimal important differences” for patient reported outcomes (i.e., the smallest changes in outcome measures that patients perceive as an important improvement or deterioration) should increasingly be defined and taken into account91. In general, it is essential to engage with patients, to include patients’ social environment in the diagnostic and therapeutic process where appropriate, to be transparent, to promote inclusivity, to ensure continuity of care, and to convey hope and perspective (see Table 1, statement 13).

Research directions

Research into clinical, (epi)genetic, proteomic, metabolomic, microbiome, physiological and neuroimaging biomarkers as predictors of treatment resistance in anxiety disorders, allowing for a more personalized and precise care in this field, was welcomed by the panel (see Table 1, statement 12). However, the very limited currently available evidence was acknowledged92-95.

Real-world data such as gait analysis or time/event-contingent actigraphy data using ecological momentary assessment might provide additional markers predicting TR-AD96-99. Machine learning approaches could aid in integrating biological, biographical and ecological momentary assessment markers82.

DISCUSSION

The present Delphi method-based consensus on operational criteria for TR-AD (see Table 2) is hoped to serve as a systematic, consistent and practical guideline to define this condition and thereby aid in designing future clinical trials for regulatory purposes as well as other research projects. This effort could ultimately lead to the development of more effective evidence-based stepped-care treatment algorithms for patients with TR-AD.

| Treatment failure |

|

|

| OR |

|

| OR |

|

|

| Pharmacological treatment resistance |

|

|

| Psychotherapeutic treatment resistance |

|

| Staging model |

|

- HAM-A – Hamilton Anxiety Scale, BAI – Beck Anxiety Inventory, CGI-I – Clinical Global Impression Scale - Improvement, SSRI – selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SNRI – serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, GAD – generalized anxiety disorder, CBT – cognitive behavioral therapy, PD/AG – panic disorder/agoraphobia, SAD – social anxiety disorder, MTR-AD – multi-modal treatment-resistant anxiety disorder

The Delphi method-based process is considered “state-of-the art” to achieve international consensus on a given research or clinical issue. The international experts and stakeholders selected for this study represent a broad range of expertise in the field. Response rates in the three separate voting rounds did not reach 100% (first round: 80.6%; second round: 94.4%; third round: 86.1%), but this corresponds to the upper part of the range of other published Delphi method-based studies, where response rates between 45% and 93% have been reported across three rounds of voting100.

The coverage of both pharmacological interventions and psychotherapies in the proposed operational criteria for TR-AD is not a common feature in currently available definitions for other treatment-resistant mental disorders, although frequently regarded as appropriate or even necessary101-103. This represents in itself an important development.

We acknowledge that experts or stakeholders outside the present panel might have differing views on how TR-AD should be conceptualized, which may limit the generalizability of the proposed criteria. Therefore, in a next step, the conceptualization of TR-AD presented here should be empirically investigated and validated. In the future, a more fine-grained and potentially dimensional definition of TR-AD, comprising multiple modalities (e.g., self-report and clinician ratings, biological/physiological recordings), covering a variety of factors (e.g., life events, treatment intolerance, psychosocial functioning, comorbidities), and incorporating a lifespan perspective, might increase construct validity and better reflect the complex and multifaceted nature of anxiety, including its waxing and waning course17, 20, 104, 105. The definition of such core outcome sets could follow the Core Outcome Set-STAndards for Development (COS-STAD)106 and Core Outcome Set-STAndards for Reporting (COS-STAR)107.

It has to be noted that the presently proposed consensus criteria for TR-AD are limited to the population of adult patients, while criteria for TR-AD in childhood and adolescence and in elderly patients remain to be established in future studies108-111. Along this line, the diagnostic entities “separation anxiety disorder” and “selective mutism”, previously classified in the DSM-IV section “Disorders Usually First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence” and now listed in the DSM-5 chapter on Anxiety Disorders112-114, warrant investigation with regard to treatment resistance in adulthood.

It is desirable to identify factors predicting and mechanistically underlying treatment resistance in anxiety disorders. Some studies of limited quality and highly heterogeneous in design suggest a number of potential risk factors – such as high expressed emotions within the family, higher severity and longer duration of the disorder, earlier age of onset, or presence of comorbid conditions – which however have not been consistently replicated13, 19, 81, 82. In a similar vein, the identification of reliable and valid biomarkers indicating an increased risk of treatment resistance would be helpful to inform algorithms for individually tailoring an intensified treatment for those patients22, 23, 25, 93, 94, 115.

To date, no internationally endorsed evidence-based guidelines exist for the treatment of patients with TR-AD. Clinical recommendations13, 18, 19, 26, 116-119 comprise switching medication within one class or to a different class; augmentation strategies with other antidepressants, antipsychotics or anticonvulsants; combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, as well as treating comorbid mental and/or somatic disorders complicating the treatment course. The present Delphi method-based consensus operational criteria for TR-AD may help to foster clinical trials probing innovative pharmacological, psychotherapeutic and non-invasive brain stimulation approaches in order to establish more effective treatment options for this condition. For instance, “third-wave” psychotherapeutic interventions such as acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, meta-cognitive therapy and compassion-focused therapy120-124, as well as novel pharmacological compounds targeting monoamines (including psychedelics), GABA, glutamate, cannabinoid, cholinergic and neuropeptide systems125, 126 might prove useful in treating TR-AD.

In sum, the presently proposed Delphi method-based consensus operational criteria for TR-AD are expected to inform both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic clinical trials for regulatory purposes towards more targeted and personalized treatment options for persons with TR-AD, thus reducing the individual and collective socioeconomic burden of anxiety disorders. If they are empirically validated, a dissemination plan could include their endorsement by professional associations and health care authorities to facilitate their implementation in practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

D.S. Baldwin, B. Bandelow, I. Branchi, J. Burkauskas, S.J.C. Davis, B. Dell'Osso, K. Domschke, N.A. Fineberg, M. Latas, V. Masdrakis, S. Pallanti, S. Pini, M.A. Schiele, N. van der Wee and P. Zwanzger are members of the Anxiety Disorders Research Network (ADRN) of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP). Supplementary information on this study is available at https://osf.io/3mjgb/?view_only=46f866499b2441958d10321a8bfa47c5.