The influence of socioeconomic status on management and outcomes in major trauma: A systematic review and meta-analysis

This paper has been accepted for presentation to the annual congress of the Association of Surgeons in Great Britain and Ireland (ASGBI), Belfast, May 2024. The abstract has been published in the British Journal of Surgery.

Abstract

Background

Major trauma is a leading cause of death and disability in younger individuals and poses a significant public health concern. There is a growing interest in understanding the complex relationships between socioeconomic deprivation and major trauma. Anecdotal evidence suggests that deprivation is associated with more violent and debilitating injuries. There remains a paucity in literature evaluating major trauma outcomes in relation to socioeconomic deprivation.

Methods

A comprehensive search of MEDLINE, Embase, and CENTRAL databases was performed to identify studies from 1947 to March 2024. The primary outcome was to establish the distribution of injuries based on deprivation, with secondary outcomes evaluating surgical intervention rates, length of stay, and mortality. Quantitative pooling of data was based on the random-effects model.

Results

Fourteen studies and 878,872 trauma patients were included. A substantial proportion (28%) of trauma incidents occurred in the most deprived group. Patients from the lowest socioeconomic group were considerably younger (weighted mean difference [WMD] −9.85 years and 95% confidence intervals [CI] −9.99 to −9.70) and more likely to be male (odds ratio [OR] 1.36 and 95% CI 1.14–1.63). There were no differences in surgical intervention (OR 1.74 and 95% CI 0.97–3.13), length of stay (WMD 1.15 days and 95% CI −0.32−2.62), and mortality (OR 1.04 and 95% CI 0.95–1.14) regardless of background.

Conclusion

Major trauma is prevalent in deprived areas and in younger individuals, with an increasing trend of deprivation in male patients. Although the rates of surgery, length of stay, and mortality did not differ between groups, planning of public health interventions should target areas of higher deprivation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Major trauma poses a significant public health concern and is the leading cause of death and disability globally.1, 2 Despite advances in trauma care and development of major trauma pathways, trauma remains a common cause of death in the younger population globally. The UK National Audit Office2 estimates that there are 20,000 cases of major trauma annually with 5400 subsequent deaths. Although data on the outcomes of trauma and its pattern of mechanisms have increasingly been described in recent years,3 little is known about the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and patient outcomes.

The injury burden from major trauma is not shared equally among all patients, with previous studies indicating that those of lower socioeconomic backgrounds being overrepresented in trauma populations.4 Social deprivation, or low SES, can be described as a limitation of access to resources due to poverty, discrimination, finances, and lack of education and is often linked to poorer health outcomes. Recent studies from the United States5-8 have indicated that social deprivation increases the likelihood of experiencing more severe and violent trauma. In addition to the increased likelihood that vulnerable patients have to suffer from traumatic injury, disparities can also exist in trauma care received and subsequent mortality.5 The reason for this is likely to be multifactorial. Patients from low SES backgrounds are less likely to have financial access to healthcare for treatment and are less likely to have access to tools for health promotion.9-11 Chronic stressors and lack of access to preventative care for comorbid conditions in patients from low SES backgrounds can also contribute to deleterious outcomes following the trauma.12

Understanding the association between SES and the management and outcomes of major trauma can be useful in the planning and provision of public health prevention programs. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to investigate these complex associations.

2 METHODS

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the guidance of the PRISMA and MOOSE statements, and the protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42024519267).

2.1 Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic search of the Medline, Embase, CENTRAL, and ClinicalTrials.gov databases was undertaken to identify relevant studies from database inception to March 19, 2024. Relevant MeSH terms and keywords relating to SES were combined with terms relating to major trauma [“socioeconomic status” odds ratio (OR) “social deprivation”] AND [“major trauma”]. The reference list of all studies that met the inclusion criteria were hand-searched for any additional suitable articles to ensure comprehensive study inclusion. The detailed search strategy can be found in Table S1.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Eligible study types are observational studies evaluating the effects of socioeconomic deprivation on outcomes in major trauma patients. Letters, case reports, case series with less than 20 participants, and systematic reviews were excluded. Studies that did not report the primary outcome measure were also excluded. The studies had to be in human subjects 18 years of age or older. There was no limitation to language of publication, sex, geographic location, or publication status.

Major trauma was defined using the UK NICE guidelines definition13 which is accepted by all the UK national trauma centers as an injury or combination of injuries that are life-threatening and could be life changing because it may result in long-term disability. For the purpose of this review, studies which included solely head and neck or orthopedic injuries were excluded from analysis as their management varies greatly. Only studies that categorized SES with a discrete or numerical value were included in this review.

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

Studies identified from the database search were screened based on their titles and abstracts by two independent reviewers (AK and GM), and studies that meet the eligibility criteria were read in full text. Duplicate studies were excluded. Any discordance was resolved by consensus with the other authors. Where multiple reports describing the study were identified, data from all reports were used if required, ensuring no duplicate counting of study participants.

A standardized data extraction form was used to document study characteristics and outcomes. This included information regarding the study design, country of origin, years conducted, patient population, and a description of the measurement of SES used by individual studies.

The primary outcome of interest is to establish the proportion of patients with a low SES that present as a major trauma. The secondary outcomes included a comparison of the age, sex, injury severity score (ISS), rate of surgical intervention, length of hospital stay, and mortality rates between the lowest and highest SES groups. The longer-term disability was also explored where reported by the level of social deprivation. The lowest SES group describes participants with the greatest level of socioeconomic deprivation.

2.4 Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias for each study was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for cohort studies. A modified NOS was used to assess the risk of bias for this systematic review. The selection criteria was rated from 1–3 stars instead of 4, as the “demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study” is not applicable for this review. An overall risk of bias score was given to each study: low, moderate, and high risk of bias.

2.5 Statistical analysis

-

0%–40% might not be important,

-

30%–60% may represent moderate heterogeneity,

-

50%–90% may represent substantial heterogeneity,

-

75%–100% considerable heterogeneity.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study selection

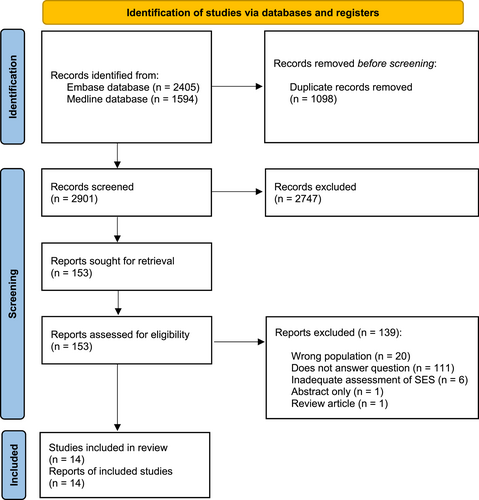

A total of 3999 studies were retrieved from the database search (Figure 1). After excluding duplicates, 2901 abstracts were screened and 154 full-text articles were identified as being potentially eligible for analysis. After a critical appraisal of the full-texts, 140 were excluded from this review. Table S2 lists potentially eligible studies that were excluded along with reasons.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Finally, 14 studies16-29 with a total of 878,872 participants met the eligibility criteria and were assessed qualitatively and quantitatively. There were 253,158 participants from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds (most deprived) and 227,756 from the highest socioeconomic backgrounds (least deprived).

3.2 Study characteristics

The included studies were published between 2000 and 2024 (Table 1). Eight studies were from Europe,17-20, 22, 24, 26, 28 four from North America,16, 23, 27, 29 one from Australia,21 and one from the Middle East.25 Ten of the studies were multicenter studies17-24, 26, 28 and four were single-center studies.16, 25, 27, 29 The included studies had varying ways of determining their study participants' SES; however, the majority used their respective government's official deprivation index tools. Of the 14 studies, 8 assigned their participants into 1 of 5 levels of deprivation (quintiles), 2 into quartiles, 2 into tertiles, and 2 into low and high SES groups.

| Author | Study design | Country and year(s) of study | Population | Subjects (n) | Determination of SES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry et al. (2024) | Retrospective | United States, 2012–2021 | Single center (regional adult trauma center) | 1044 | SES determined by area of deprivation index (ADI) tool and official United States Census Bureau. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 SES quintiles. | |||||

| Snell et al. (2023) | Retrospective | United Kingdom, 2014–2019 | Multicenter | 7666 | SES determined by English official index of multiple deprivation 2019 (IMD) stool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 SES quintiles. | |||||

| Moksnes et al. (2023) | Prospective | Norway, 2020 | Two regional trauma centers | 601 | SES determined by Norwegian Centrality Index (NCI) tool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 3 tertiles. | |||||

| Madsen et al. (2022) | Retrospective | Norway, 2008–2014 | Multicenter | 177,663 | SES determined by education, income, and occupation (calculation and assignment of index performed by the study investigators). |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 quintiles. | |||||

| Popal et al. (2021) | Retrospective | Netherlands, 2015–2017 | Two regional trauma centers (level 1) | 967 | SES determined by statistics Netherlands (CBS) and The Dutch Institute for Social Research (SCP). |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 quintiles. | |||||

| Giummarra et al. (2021) | Retrospective | Australia, Jan 2009–Jun 2017 | Multicenter | 1003 | SES determined by the index of relative socio-economic advantage and disadvantage (IRSAD) tool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 quintiles. | |||||

| Bege et al. (2019) | Retrospective | France, 2016 | Multi-center | 137,944 | SES determined by the French area-level deprivation index (FDep99 index) tool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 4 quartiles. | |||||

| Sall et al. (2018) | Retrospective | United States, 2006–2014 | Multi-center | 407,553 | SES determined by the United States Census Bureau. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 4 quartiles. | |||||

| McHale et al. (2018) | Retrospective | United Kingdom, 2015 | Multicenter (using the national trauma database, TARN) | 48,658 | SES determined by English official index of multiple deprivation 2019 (IMD) stool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 SES quintiles. | |||||

| Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi. (2018) | Retrospective | Iran, 2014–2015 | Single center | 570 | SES determined on asset index (by performing principal component analysis by the study investigators). |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 3 tertiles. | |||||

| Devos et al. (2017) | Retrospective | Belgium, 2009–2011 | Multicenter | 64,304 | SES determined by entitlement to reduced payments for healthcare services. |

| Study subjects are assigned either low or high SES. | |||||

| Mikhail et al. (2016) | Retrospective | United States, 2000–2009 | Single center | 4007 | SES determined by the United States Census Bureau. |

| Study subjects are assigned either low or high SES. | |||||

| Corfield et al. (2016) | Retrospective | Scotland, 2011–2012 | Multicenter (using the national trauma database) | 9238 | SES determined by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2012 tool. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 quintiles. | |||||

| Zarzaur et al. (2010) | Retrospective | United States, 1996–2005 | Single center | 17,658 | SES determined by the United States Census Bureau. |

| Study subjects are assigned one of 5 quintiles. |

3.3 Meta-analysis

3.3.1 Demographics

Fourteen studies reported on the SES of patients presenting as a major trauma, with 28% (95% CI 24%–31%) of all patients coming from the most deprived backgrounds (Figure S1a). There was a considerable statistical heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 99.86%).

Five studies16, 18, 20, 23, 29 reported on the average age of patients from each socioeconomic group. Major trauma patients from the lowest socioeconomic group were considerably younger compared to the highest (WMD −9.85 years, 95% CI −9.99 to −9.70, see Figure S1b). However, there was, a considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 99%).

Seven studies16, 18, 20, 22-24, 29 reported on the sex of patients across all socioeconomic groups. Male patients were more likely to derive from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.14–1.63, and I2 = 98%; see Figure S1c).

Four studies16, 20, 23, 29 reporting on ISS across patients from all socioeconomic backgrounds found that there were no significant differences between the most- and least-deprived groups (WMD −0.85, 95% CI −2.38 to 0.69, and I2 = 96%; see Figure S1d).

3.3.2 Patient outcomes

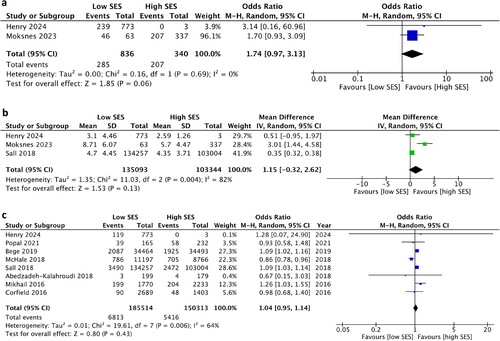

Two studies16, 18 reported on the rate of surgical intervention across major trauma (Figure 2A). There were no statistically significant differences between the most- and least-deprived groups (OR 1.74, 95% CI 0.97–3.13, and I2 = 0%).

(A) Meta-analysis of rate of surgical intervention in low versus high SES groups. (B) Meta-analysis of length of hospital stay in low versus high SES groups. (C) Meta-analysis of mortality in low versus high SES groups. SES, socioeconomic status.

Three studies16, 18, 23 reporting on the length of hospital stay found that there were no significant differences between the two socioeconomic groups (WMD 1.15 days and 95% CI −0.32 to 2.62; see Figure 2B).

Eight studies16, 20, 22-25, 27, 28 reporting on mortality rates found that there were no significant differences in mortality between the most and least deprived groups (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.95–1.14, and I2 = 64%; see Figure 2C).

3.4 Disability

Two studies21, 25 reported post-trauma disability, one21 at 6-, 12- and 24-months and another25 at 1- and 3-months. One21 study reported that there was a trend of increasing disability (problems with pain, anxiety and depression, mobility, self-care, and activities of daily living) with lower SES groups. Another study25 did not report any differences in disability across SES groups. Pooled analysis was not possible due to the lack of data.

3.5 Risk of bias

The risk of bias was evaluated using the NOS (Table 2). Overall, 8 studies had a low risk of bias,20-24, 27-29 whereas 4 studies had a medium risk of bias16, 19, 25, 26 and 2 studies had a high risk of bias.17, 18

| Study | Risk of bias assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Overall score | |

| Henry et al. (2024) | *** | - | ** | 5 |

| Snell et al. (2023) | *** | - | - | 3 |

| Moksnes et al. (2023) | *** | - | - | 3 |

| Madsen et al. (2022) | *** | ** | - | 5 |

| Popal et al. (2021) | *** | ** | ** | 7 |

| Giummarra et al. (2021) | *** | * | *** | 7 |

| Bege et al. (2019) | *** | - | *** | 6 |

| Sall et al. (2018) | *** | ** | ** | 7 |

| McHale et al. (2018) | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi et al. (2018) | *** | - | ** | 5 |

| Devos et al. (2017) | *** | * | - | 4 |

| Mikhail et al. (2016) | *** | ** | ** | 7 |

| Corfield et al. (2016) | *** | ** | *** | 8 |

| Zarzaur et al. (2010) | *** | ** | ** | 7 |

- Note: Risk of bias: 6 or above, low risk; 4 or 5, medium risk; and 1–3, high risk.

4 DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis of 14 studies found that a considerable proportion of major trauma incidents occurred in younger individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds, with an increasing trend of deprivation in male patients. Importantly, there were no differences in the rate of surgical intervention, length of hospital stay, and mortality between the most and least deprived population. There was considerable statistical heterogeneity across the meta-analysis for the outcomes of proportion of significant socioeconomic deprivation, age, sex, ISS, and mortality. This was not unexpected as the population and methodology used to determine the participants' SES varied across the 14 studies.

Historical epidemiological data have described that major trauma is predominantly a disease of young men,30, 31 but recent studies32, 33 have suggested that the trauma population may gradually be changing to reflect an aging population due to improvements in healthcare and consequently prolonging life expectancies. Despite this, thirteen of the fourteen studies included within this systematic review were published within the last decade and still showed an ongoing trend of young male patients from low socioeconomic backgrounds. In the United Kingdom, young males are substantially more likely to be involved in violence and knife crime, both as perpetrators and victims.34-36 Exposure to violence increases the risk of alcohol and drug abuse37 and consequently injuries requiring a major trauma admission. These risks increase further with increasing levels of deprivation.9, 38-40 This supports the findings of this present study, where majority of the patients were young, male, and from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding the complex relationships between SES and major trauma admissions. Deprivation-related stressors, unemployment, homelessness, inadequate access to community resources, including sporting opportunities in youth, and social isolation all create a disparity in trauma rates. Previous studies17, 41 have demonstrated that socioeconomically deprived individuals are more likely to participate in high-risk behaviors, which increases the risk for injuries. Despite a disparity in the demographics of major trauma patients, this present review has importantly highlighted that the management and mortality rates do not differ across different socioeconomic groups. Previous studies have demonstrated that acquired in-hospital complications, preexisting chronic conditions, and lack of access to care for comorbid conditions in patients from deprived backgrounds can also worsen outcomes following major trauma.12, 42 The NHS healthcare model in the United Kingdom means that all healthcare is free at the point of use, which reduces inequalities of access to healthcare found in several other countries. In England, the majority of trauma is attended to by a trauma team and specialist trauma centers; evidence suggests that this model has led to improvements in outcomes.43 Better access to healthcare is also associated to reductions in inequalities of mortality across Europe.43

Patients who have suffered moderate and severe traumatic injuries often face challenges in the post-discharge recovery, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), pain, cognition issues, other physical disability, and failed return to work.44-47 These issues are often compounded in individuals from deprived backgrounds due to stigma and reduced social and financial support. There is growing evidence to show that improved access to work is associated with better health and quality of life.48 Improved access to early and continued rehabilitation and involvement of a multidisciplinary team can support patients recover with adequate psychological, emotional, and physical support.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis examining the association between SES and the management and outcomes of patients presenting as a major trauma, which has highlighted the discrepancies in the demographics of patients between the lowest and highest SES groups. Despite this, the present analysis has some limitations. While this systematic review included 14 studies and over eight hundred thousand patients, some studies had smaller sample sizes (three studies had less than 1000 patients). Post-injury disability was only reported in 2 studies, of which only one21 reported long-term disability at 24 months. There was a significant heterogeneity in the data across all outcome measures. This is likely due to the diversity in the population and methodology used across the 14 studies. The criteria for determining levels of socioeconomic deprivation varied between the studies. Although most study investigators relied on official and recognized government index of multiple deprivation tools, three performed their own calculations to assign participants into a socioeconomic group. For the purposes of the present analyses, outcomes were compared between the lowest and highest SES groups. Although majority of the study investigators presented their patients' SES as quintiles (five equal groups), others presented SES as either two, three, or four groups. Therefore, this variation in the determination of participants' SES may explain the heterogeneity in the data across all outcome measures.

Information on functional outcomes is crucial to evaluate the full impact of trauma including disability, quality of life, lost income, social care, and direct healthcare costs. However, there is a lack of available data on functional outcomes following major trauma from the included studies. Future research should focus on long-term outcomes of the different socioeconomic groups following major trauma. There is a need to explore functional outcomes to understand how individuals from different socioeconomic backgrounds recover from injury in order to understand the long-term burden of trauma. Further larger studies are required to explore the impact of SES on the mechanism of action, management, in-hospital, and long-term outcomes of major trauma. Finally, identifying those at the highest risk of injury and subsequent poor outcomes can help develop and prioritize key issues in public health policies and strategies that could help prevent major trauma.

5 CONCLUSION

Major trauma is more prevalent in deprived areas; younger males, from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, are more likely to be presenting with blunt or penetrating trauma injuries. However, there was, no difference in the rates of surgery, length of stay, and mortality between the most and least deprived groups following presentation—a likely beneficial effect of level 1 trauma units with centralized expertise. Nonetheless, the currently available literature remains sparse regarding the longer-term disability and outcomes following major trauma injuries based on levels of deprivation.

In future, the planning of public health interventions should be targeted at areas of higher deprivation to diminish the impact of avoidable traumatic injuries especially in younger males.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Amanda Koh: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing–review & editing. Alfred Adiamah: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; supervision; validation; visualization; writing - original draft; writing—review & editing. Georgia Melia: Project administration; resources; software; writing - original draft; writing—review & editing. Lauren Blackburn: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Adam Brooks: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; resources; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There was no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was not necessary as this was a systematic review.

PROTOCOL REGISTRATION

The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42024519267).