Clinical and computed tomography outcomes after mesh-enforced hiatoplasty and anterior hemi-fundoplication in large hiatal hernia repair

The abstract of the paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Swiss College of Surgeons in Basel, Switzerland, 2023.

Julian Süsstrunk and Daniel Stimpfle contributed equally to this manuscript.

Abstract

Background

The surgical technique in large hiatal hernia (HH) repair is controversially discussed and the outcome measures and follow-up schemes are highly heterogeneous. The aim of this study is to assess the true recurrence rate using computed tomography (CT) in patients with standardized large HH repair.

Methods

Prospective single-center study investigating the outcome after dorsal, mesh-enforced large HH repair with anterior fundoplication. Endoscopy was performed after 3 months and clinical follow-up and CT after 12 months.

Results

Between 2012 and 2021, 100 consecutive patients with large HH were operated in the same technique. There were two reoperations within the first 90 days for cephalad migration of the fundoplication. Endoscopic follow-up showed a correct position of the fundoplication and no relevant other pathologies in 99% of patients. Follow-up CT was performed in 100% of patients and revealed 6% of patients with a cephalad slippage, defined as migration of less than 3 cm of the wrap, and 7% of patients with a recurrent hernia. One patient of each group underwent subsequent reoperation due to symptoms. There was no statistical correlation between abnormal radiological findings and clinical outcomes with 69.2% of patients being asymptomatic. Multivariate logistic regression did not show any prognostic factor for an unfavorable radiologic outcome. Ninety-four percent of patients rated their outcomes as excellent or good.

Conclusion

Radiological follow-up after large HH repair using CT allows to detect slippage of the fundoplication wrap and small recurrences. Patients with unfavorable radiological outcomes rarely require operative revision but should be considered for further follow-up.

1 INTRODUCTION

The most recent SAGES Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernias strongly recommend the operative treatment of symptomatic paraesophageal hernias but do not give clear recommendations on the various technical aspects. The laparoscopic approach, the repositioning of the gastroesophageal junction and herniated organs in to the abdominal cavity, and the dissection of the mediastinal hernia sac are recommended. More controversially discussed is the use of a mesh for the repair of the hiatus or the kind of stomach fixation in the abdomen.1

Several randomized trials investigated the recurrence rate after the use of nonabsorbable mesh versus suture alone in the repair of hiatal hernia (HH).2-4 Generally, the short-term results were in favor of mesh-enforced techniques. The long-term benefit of mesh enforcement of the hiatal suture repair was not observed in most reports including a recent meta-analysis from Australia.5-7 Regardless of mesh-enforcement, the long-term recurrence rate after >10 years can amount up to 50%, interestingly often being asymptomatic and not affecting quality of life (QoL).8

However, there are several important limitations in the current literature, such as a large heterogeneity of the surgical techniques and follow-up methods, as discussed in a recent statement by Rajkomar et al. and confirmed in a recent survey amongst visceral surgeons in 2021.9, 10

Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyze and correlate the clinical and computed tomography (CT) outcome at least 1 year after repair of types II, III, or IV large hiatal hernias in a consecutive cohort of patients, all operated using a standardized technique.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

This combined retro- and prospective, single-center, single-arm study included patients operated between 2012 and 2021 undergoing minimally invasive repair of large HH. Last time point of data collection was December 31, 2022. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (ZHEK BASEC 2016-01510) and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03025932). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after full explanation of the purpose and nature of each intervention.

2.2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria/preoperative investigations

All patients older than 18 years with types II, III, and IV hiatal hernias were assessed for eligibility. The indication was set if >20% of the stomach was intrathoracic and the patient was symptomatic or if >50% was in the chest, independent of symptoms, as seen on a preoperative CT-scan. For patients who underwent another form of HH operation, an emergency procedure or revisional surgery were excluded.

Preoperative workup consisted of a detailed patient history, physical examination, and preoperative imaging as reported in Table 1 and upper endoscopy. Routine pH-studies were not performed and manometry was only performed if any suspicion of an esophageal motility disorder was present.

| Factor | Patients |

|---|---|

| N | 100 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 67 |

| Male | 33 |

| Age at operation, mean (SD) | 70.9 (10.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.1 (4.7) |

| ASA class | |

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 64 |

| 3 | 31 |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 35 |

| Public | 65 |

| Use of PPI, preoperative | |

| High dose (Pantoprazole ≥ 40 mg or equivalent) | 14 |

| Low dose (Pantoprazole 20 mg or equivalent) | 58 |

| None | 28 |

| Imaging, preoperative | |

| CT | 96 |

| Barrel chest | 0 |

| Hyperkyphosis (Cobb-angle >50°)11 | 12 |

| Distance sternum to vertebrae (in level of hiatus, cm) | 14.9 ± 2.3 |

| Barium X-ray | 1 |

| None (endoscopy only) | 3 |

| Hernia type | |

| II | 15 |

| III | 62 |

| IV | 23 |

| % of intrathoracic migrated stomach | |

| >20% | 100 |

| >50% | 65 |

| >90% (upside down stomach) | 23 |

| Mean operation time, in minutes (SD) | 152 (45) |

| Concomitant procedures | 13 |

| Cholecystectomy | 6 |

| Mesh-enforced ventral hernia repair | 3 |

| Other (adhesiolysis, two benign tumor excisions). | 3 |

| Crural stitches (SD) | 5.3 ± 1.2 |

| Intraoperative complications (ClassIntra) | 6 |

| Grade 1: Minor splenic bleeding | 2 |

| Grade 1: Pleura injury | 1 |

| Grade 2: Serosa lesion stomach, sutured | 1 |

| Grade 2: Pneumothorax demanding chest tube | 2 |

| Length of stay (SD) | 4.2 (2.2) |

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CT, computed tomography; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; SD, standard deviation.

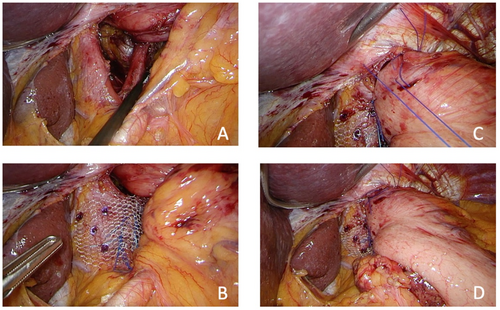

2.3 Operative procedure

Using four ports and a Nathanson liver retractor, the herniated peritoneal sac and the stomach were repositioned into the abdominal cavity under preservation of the anterior and posterior vagus nerve. The esophagus was mobilized to ensure an intra-abdominal length of at least 2–3 cm. A posterior tension-free hiatoplasty over a 52 French Maloney bougie was performed with multiple single-stitch, monofilament, and nonresorbable sutures (NovafilTM 2-0, CovidienTM). An approximately 3 by 6 cm tailored, nonresorbable mesh (Parietex Mono™, Covidien Medtronic or Bard® Soft Mesh) was attached with resorbable polymer-tacks (AbsorbaTack™, Covidien Medtronic) posteriorly on both pillars to reinforce the suture. The angle of His was reconstructed and a 180° anterior hemi-fundoplication was created with six nonabsorbable NovafilTM 2-0 sutures (see Figure 1). Drains were not routinely inserted as we believe that they cannot be left long enough to safely drain the developing seroma in the former hernia space.

Intraoperative images of the standardized procedure: (A) Large hiatal hernia (HH) with stomach and distal esophagus repositioned intra-abdominal. (B) Closed HH with Novafil 2-0™ stitches and mesh-reinforcement using absorbable tackers. (C) Crown stitches performed in anterior fundoplication between the wrap and the diaphragm at 11, 12, and 1 o'clock. (D) The remaining stitches are made at 8 o'clock and 10 o'clock from the stomach to the esophagus and to the hiatal repair.

2.4 Postoperative care and follow-up

Routine clinical follow-up was performed after 6 weeks, 6 months and, 1 year and 3 years. Follow-up upper endoscopy was performed after 3 months. For the study, all patients underwent a CT scan after a minimum of 12 months postoperatively. Patients operated between 2012 and 2015 were retrospectively asked to participate in the CT follow-up, and starting in 2016, every patient was prospectively included in the CT follow-up.

2.5 Outcome measures

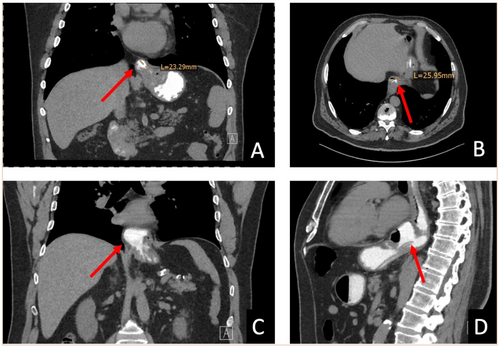

The primary outcome was the radiological recurrence rate determined by CT of the abdomino-thoracic junction with oral on-table contrast. As the CT allows to analyze the postoperative situs in detail, we defined three possible situations: all parts of the stomach and the wrap, including the gastroesophageal junction, were inferior of the diaphragm (=correct anatomical outcome); dislocation of a small part of the wrap, measuring not more than 3 cm, through the nonenlarged hiatus (=slippage, presumably not visible in conventional contrast study, see Figure 2A,B); and parts of the stomach or wrap located in the thoracic cavity, that is, cephalad of the diaphragm (=recurrence, see Figure 2C,D). The two latter situations were considered to be an unfavorable radiological outcome.

Computed tomography of a slippage ((A) coronary view and (B) axial view) and of a recurrent hernia ((C) coronary view and (D) sagittal view) after anterior fundoplication. The affected part of the stomach is marked with a red arrow.

Secondary outcomes were the QoL, assessed by the validated Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index questionnaire, as well as visual analog scale questions (VAS: 1 = no symptoms and 10 = maximum symptom score) for symptoms, such as pain, reflux, dysphagia, bloating, belching, and flatulence, at 12 months postoperatively.12 Furthermore, patient-reported outcomes were assessed by overall satisfaction (1 = poor, 2 = average, 3 = good, and 4 = excellent overall outcome) and willingness to perform operative treatment again (0 = no and 1 = yes). Other parameters such as peri- and postoperative morbidity and mortality and findings at the regular 3 months' postoperative endoscopy are additionally reported.

2.6 Statistical considerations

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median with 95% confidence interval as appropriate. Comparison between groups were performed using Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. To identify risk factors for radiological recurrence, univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed. A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics

Between 2012 and 2021, 107 patients were operated for primary large HH. Seven patients were excluded for either receiving another technique than described above in an emergent setting (n = 3) or because they declined to participate in the follow-up (n = 4). Thus, 100 patients were included in the analysis. Mean age was 70.9 ± 10.6 years, 67% were female and mean body mass index (BMI) was 28.1 ± 4.7 kg/m2. HH size was >20% in all patients and 23% of patients had a (near) total herniation of 90%–100% of the stomach into the thoracic cavity. Three patients did not have preoperative imaging: two patients showed very large hiatal hernias in preoperative endoscopy and did not want to undergo an additional CT and one patient had an external barium swallow of which only the report was available. All relevant baseline characteristics and perioperative data are displayed in Table 1.

3.2 Postoperative morbidity and mortality

There were nine postoperative complications within the first 30 days. Grade II complications according to Clavien–Dindo included urinary tract infections (n = 3), delayed gastric emptying (n = 1), congestive heart failure (n = 1), and one postoperative mediastinal hematoma that demanded a blood transfusion. There was one grade 3a complication with a pleural effusion demanding a pleural drainage. There were two reoperations (grade 3b): one early intrathoracic migration of the fundoplication that demanded operative revision and one small bowel necrosis that demanded resection, and the etiology was linked to a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

In the midterm follow-up, there was another reoperation after 65 days due to a symptomatic early migration of the fundoplication. There was no mesh erosion or operation-linked mortality in the entire follow-up period.

3.3 Endoscopic and radiological outcome

In 93 patients who received an upper endoscopy after 14 ± 8 weeks, 92 had a correct position of the fundoplication wrap. In one patient, a slippage of the wrap was suspected but not confirmed in the subsequently performed CT scan. The remaining seven patients either declined to undergo an endoscopy or had a medical condition unrelated to the operation that prohibited the endoscopy.

Radiological follow-up with CT was performed in all 100 patients after a median of 13 months (range 12–62 months). Eighty-seven patients (87%) had a correct position of the fundoplication with the entire stomach in the abdominal cavity. Six patients (6%) showed a slippage and seven patients (7%) showed a recurrent hernia.

3.4 Clinical outcome

The clinical outcome was assessed on the same day of the CT. Eighty-six patients (86%) had no proton pump inhibitors (PPI) medication at the time of follow-up and 11 patients (11%) required a lesser dose in comparison to the preoperative PPI intake. The main complaints after anterior fundoplication were increased flatulence, bloating, and early satiety. There were no medical, endoscopic, or surgical treatments necessary for dysphagia and mean VAS for dysphagia was 1.3 ± 1. Ninety-four patients (94%) rated their surgical outcomes as either excellent (n = 84, 84%) or good (n = 10, 10%) and 98 patients (98%) reported that they would perform the surgical procedure again.

Of the six patients (6%) with a slippage in CT follow-up, four patients rated their outcomes as excellent and two patients as “fair.” One patient due to increased bloating and early satiety and another patient due to dysphagia and reflux symptoms. The latter patient underwent operative revision. Of the seven patients (7%) with a recurrent hernia in the CT follow-up, five patients rated their outcome as excellent or good and did not show relevant side effects. Two patients rated their outcome as “fair” or “poor,” due to bloating, early satiety, and reflux, and the latter patient subsequently underwent operative revision.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical, endoscopic, and radiological outcomes.

| Follow-up upper endoscopy | 93 |

| Time to follow-up endoscopy (weeks) (SD) | 14 (8) |

| Correct position of fundoplication | 92 |

| Suspected migration | 1a |

| Midterm clinical and radiological follow-up | 100 |

| Median time to follow-up (months) (range) | 13 (12–62) |

| PPI needed | |

| No | 86 |

| Less than preoperatively | 11 |

| Unchanged | 2 |

| More | 1 |

| VAS dysphagia | 1.3 (1) |

| VAS bloating | 2.5 (2) |

| VAS flatulence (SD) | 4.5 (2) |

| VAS reflux (SD) | 1.3 (1) |

| VAS retrosternal burning (SD) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| VAS epigastric pain (SD) | 1.3 (1) |

| VAS early satiety (SD) | 2.2 (1.9) |

| Belching/vomiting possible | 83 |

| Mean GIQLI (maximum score 144) (SD) | 126 (13.5) |

| Clinical outcome | |

| Excellent | 84 |

| Good | 10 |

| Fair | 5 |

| Poor | 1 |

| Would perform surgery again | 98 |

| Wrap position in computed tomography | |

| Correct position | 87 |

| Slippage | 6 |

| Recurrent hernia | 7 |

| Reoperations | |

| Early migration (after 2 and 65 days, respectively) | 2 |

| Symptomatic slippage | 1 |

| Symptomatic recurrent hernia | 1 |

- Abbreviations: GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

- a Suspected migration of fundoplication, not confirmed in computed tomography.

3.5 Subgroup analysis

Regarding the 23 patients with preoperative total (100%) or near total (>90%) herniation of the stomach, radiological outcome showed three recurrent hernias (13%) and two slippages (8.7%). One patient (4.3%) needed to be reoperated due to a symptomatic slippage.

Compared to the rest of the cohort (77 patients with four recurrences and four slippages), the subgroup with >90% of herniated stomach did not show a significantly higher rate of recurrences/slippages (p = 0.11).

In the multivariate logistic regression using the stepwise backward selection, no parameter (age, sex, BMI, percentage migrated stomach, hyperkyphosis, and distance sternum to vertebrae) was an independent prognosticator for recurrence or slipping as shown in Table 3.

| Recurrence/slippage at radiological follow-up | Odds ratio | 95% Conf. interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.01 | 0.08 |

| Male versus female | 5.04 | 0.88 | 28.75 | 0.07 |

| Distance sternum to vertebrae | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.11 |

| Hernia size (Ref. <50%) | ||||

| >75% intrathoracic stomach | 3.03 | 0.83 | 11.12 | 0.1 |

- Abbreviation: Ref.: reference.

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, all patients underwent a CT-scan at least 1 year after the surgical repair of a large HH, regardless of the presence of symptoms. The major strength is the nearly complete follow-up rate, both for the radiological and clinical parameters, as well as a standardized operative technique. The CT follow-up allows to analyze the postoperative hiatus and wrap anatomy in detail, and we suggested to differ between small slippages of the fundoplication wrap, which would not have been diagnosed clinically nor with barium swallow nor endoscopy and true recurrences. Despite the former being mostly asymptomatic, they may increase in size over time or account for some symptoms, as seen in one of the patients needing revisional surgery. Therefore, both slippage and true wrap migration were considered as a radiologically unfavorable outcome. There was a poor correlation between radiological and clinical findings with most patients rating their outcome as excellent or good. Nine of the 13 patients (69.2%) with an unfavorable radiological outcome were completely asymptomatic. This strongly highlights that being asymptomatic does not indicate the correct position of the wrap. Most studies examined patients only if they were symptomatic, thus not showing the true amount of postoperative wrap migration.8, 13-15 The finding of a herniation of parts of the wrap does not per se mandate revisional surgery. However, it is still important to know whether the wrap is placed correctly, to decide whether an additional follow-up is necessary. This cohort remains under clinical and radiological supervision with a planned CT scan 3 years postoperatively to investigate the midterm outcomes and to assess whether the slippages progress to a recurrent hernia. Furthermore, the longer follow-up will show whether the anatomical dislocation will lead to symptoms requiring a reoperation.

Regarding the unfavorable radiological outcomes, the multivariate logistic regression did not show any specific risk factors. One would assume that the size of the hernia and/or amount of herniated stomach should influence the outcome, but this was not the case in this cohort. The present surgical technique includes a thorough mobilization of the esophagus in the mediastinum to ensure a minimal intra-abdominal length of 2 cm. There were no cases, where a Collis gastroplasty was necessary. However, we believe that the Collis is not an ideal procedure and hence, we should try to avoid it at all costs. We assume that this would not be favorable, as acid producing gastric cells would remain above the gastroesophageal junction and the fundoplication, thus exposing the patients to acid-associated issues. We could show in a large cohort of bariatric patients that a relevant number of acid-producing cells are found in the cardia and lead to a high rate of marginal ulcers due to acid exposure.16, 17

Theoretically, anatomical features, such as a hyperkyphosis, Barrel chest, or a long distance between sternum and vertebrae suggesting a flattened diaphragm may influence the recurrence rate in patients undergoing large HH repair. In the present cohort, these conditions were not identified as risk factors for recurrence.

There is an intense discussion in the literature regarding the necessity of mesh enforcement of the hiatal repair.5, 18 The mesh-enforced HH repair seems to be an advantage in terms of total recurrences over a suture-alone repair according to the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis. However, the heterogeneity of data included in that review is reported to be high, especially concerning the mesh-type and position, so the true effect remains unclear.19 In our cohort, there was no mesh-related morbidity within the follow-up period, especially no mesh-associated esophageal penetrations or perforations. The posterior mesh enforcement of the cruroplasty with minimal contact to the esophagus, thus avoiding a circular mesh around the esophagus, is thought to be the main reason to prevent mesh-associated complications but likely provides a good reinforcement of the crura, which are often thin and fragile. These results with a true recurrence rate of only 7% and a slippage rate of 6% indicate that this limited use of a mesh dorsally may be giving enough stability of the hiatoplasty. Even when the small CT-detected slippages are included in the overall recurrence rate, our results are at least comparable if not lower to the currently published series with similar sized hiatal hernias as demonstrated in Table 4.

| Study authors | Journal and publication year | # Patients | Hiatal hernia types | Operative technique | Follow-up rate and duration | Follow-up modality | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Süsstrunk et al.17 | WJS, 2024 | 100 | II–IV, more than 20% stomach herniated | Mesh-enforced in 100% and anterior fundoplication | 100% | CT | 13% (6% slippage and 7% recurrence) |

| Median 13 months (range 12–62) | |||||||

| Hietaniemi et al.20 | BMC Surg, 2020 | 165 | III and IV, more than 30% stomach herniated | Mesh-enforced in 4.2% | 59% | CT | 29.3% (includes operative revision and CT follow-up) |

| Nissen fundoplication in 90.3% | Median 39 months (12–79) | ||||||

| Nguyen et al.21 | JOGS, 2023 | 862 | III in 87.4%, more than 40% herniated | No mesh-enforcement | N/A | Endoscopy and barium swallow | 27.4% |

| Nissen fundoplication in 97.6% | 33 months (IQR 16,68) | ||||||

| Priego et al.22 | Hernia, 2024 | 67 | III | Mesh-enforced in 100% | 85% | Barium swallow | 22.4% (radiological) |

| Nissen fundoplication in 74.6% and Toupet in 25.4% | Median 41 months |

- Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; IQR, interquartile range.

Regarding the type of fundoplication, the balance of reflux control, intra-abdominal anchoring of the fundoplication, and side effects, such as dysphagia and bloating, must be found. Since most large hiatal hernias occur in elderly patients esophageal, motility disorders are common due to a chronically distorted esophageal lumen.23 In most patients, especially in type IV hernias, reflux symptoms are not prominent, most probably because the twisted stomach creates a valve toward the esophagus. Thus, anterior fundoplication seems to provide sufficient reflux control in these patients with a low rate of side effects, as seen in studies for anti-reflux surgery in the absence of large hiatal hernias.24, 25 Postoperative dysphagia was rare and there were no dysphagia-associated interventions such as dilatations or wrap revisions. PPI treatment could be stopped or reduced in over 90% of patients indicating a good reflux control, which was confirmed in postoperative endoscopy, showing no reflux-associated pathologies.

Regarding the radiological outcome, there is currently only one retrospective study reporting on the CT outcome after large HH repair.20 However, in this study, different hiatoplasty techniques were applied, roughly 10% did not receive a fundoplication at all and the CT follow-up rate was only 59%. Most other studies assessed the clinical outcome with questionnaires, some used barium X-ray or endoscopy to assess the recurrence rate of HH.4-8 One study reported on mesh shrinkage in a single-center experience using MRT-visible meshes in HH repair, including 18 patients in the analysis. No mesh-related complications or recurrences were found; however, the number of patients examined is too low to draw any conclusions.26

The overall patient satisfaction is high and 98% of patients reported that they would perform the procedure again. This finding is in line with other reports, showing a promising long-term patient satisfaction, independent of the endoscopic and radiological outcomes.13 It also highlights, together with the low-risk profile that minimal invasive repair of giant hiatal hernias is safe and increases QoL, even in an elderly cohort of patients.

Some limitations of this study need mentioning. It is a single-center design and there is no control group. However, the single-center approach with one surgeon present in all procedures guaranteed a homogenous and comparable operative technique. Furthermore, this allowed to present a cohort with a nearly complete follow-up rate, higher than in any other published paper. There was no control-group, because the radiological outcome of this explicit repair technique was the primary endpoint. The number of slippages or wrap migrations was low, and one may argue that it has not reached statistical power in the logistic regression and therefore did not identify previously described risk factors for recurrence such as age or HH size.21, 27 Still, together with the missing differences in the sub-analysis of patients with preoperative (near) total upside down stomachs compared to lesser amounts of migration, it indicates that the presented technique is well suited.

5 CONCLUSION

Radiological follow-up after large HH repair using CT allows to detect small slippages of the fundoplication wrap and true recurrences. There is a poor correlation between radiological and clinical outcomes. Patients with unfavorable radiological outcomes rarely require operative revision but should be considered for further follow-up to detect deterioration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Julian Süsstrunk: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Daniel Stimpfle: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Alexander Wilhelm: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Enea Marco Ghielmini: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Silke Potthast: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. Urs Zingg: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. P. Heeb and Ms. S. Tanner, scientific assistants, for their great contribution to the success of this study. The study was funded with a hospital internal research fund. There was no external or commercial funding.

Open access funding provided by Universitat Basel.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Julian Süsstrunk, Dr. Daniel Stimpfle, Dr. Alexander Wilhelm, Dr. Enea Marco Ghielmini, PD Dr. Silke Potthast and Prof. Urs Zingg have contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, have drafted or revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content, approve the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.