Gastrointestinal Perforations Associated With JAK Inhibitors: A Disproportionality Analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Gastrointestinal perforations have been reported in a small number of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in clinical trials. However, large-scale postmarketing data repositories are needed to further investigate this potentially rare but serious adverse event.

Methods

A retrospective, pharmacovigilance study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (July 2014 to September 2023) assessing the reporting of gastrointestinal perforations following JAK inhibitors compared to biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) in RA patients. The adjusted reporting odds ratio (adj.ROR) was calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

Of 399,983 RA patients included in the study, 76,446 were treated with JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, n = 52,365; upadacitinib, n = 21,856; baricitinib, n = 2225) and 323,537 were treated with bDMARDs (TNF inhibitors, rituximab, and abatacept). Overall, 230 cases of gastrointestinal perforation following JAK inhibitors were identified, with a median time of 9 (IQR: 4–22) months from treatment initiation. Compared with bDMARDs, JAK inhibitors were associated with a higher-than-expected reporting of gastrointestinal perforations (adj.ROR = 1.98[1.69−2.31]). Increased reporting of gastrointestinal perforations was observed among recipients of JAK inhibitors or bDMARDs who used steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs concurrently (adj.ROR = 2.82 [2.41–3.31]). Perforations of both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract were significantly over-reported (n = 51, adj.ROR = 1.55 [1.12–2.14], n = 143, adj.ROR = 1.78 [1.46–2.17], respectively). Furthermore, the safety signal was significant across all JAK inhibitors: tofacitinib (n = 125, adj.ROR = 1.52 [1.25–1.85]), upadacitinib (n = 84, adj.ROR = 2.73 [2.17–3.44]), and baricitinib (n = 21, adj.ROR = 5.38 [3.46–8.37]).

Conclusion

In this global pharmacovigilance study, all JAK inhibitors were associated with increased reporting of gastrointestinal perforations compared with bDMARDs in RA patients. Until more data on IBD patients emerge, careful surveillance and increased clinicians' awareness should also be advocated for this population.

Summary

-

Summarize the established knowledge on this subject

- ◦

Gastrointestinal perforations (GIPs) were first identified in pivotal clinical trials of JAK inhibitors, with additional cases reported in subsequent long-term extension studies.

- ◦

These findings prompted the FDA to recommend the cautious use of JAK inhibitors in patients at risk for GIP, such as those with a history of diverticulitis or peptic ulcer disease, and individuals receiving concurrent treatment with steroids or NSAIDs.

- ◦

Large-scale, post-marketing, long-term data on this rare but serious adverse event remain limited.

- ◦

-

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

- ◦

This pharmacovigilance study, using the global postmarketing surveillance program of the FDA, identified 230 cases of GIP following treatment with JAK inhibitors.

- ◦

JAK inhibitors were associated with a two-fold increased reporting of GIPs compared with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Perforations of both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts were significantly over-reported.

- ◦

The safety signal was consistent across all JAK inhibitors studied (tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib), suggesting a potential class effect.

- ◦

Concomitant treatment with steroids or NSAIDs was a significant risk factor for GIP reporting.

- ◦

1 Introduction

Gastrointestinal perforations (GIPs) are a source of concern in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, primarily related to the use of steroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and biological agents [1-3]. In the prebiologic era, most reported GIPs in RA patients involved the upper gastrointestinal tract and were largely attributed to NSAID treatment [4]. With the advent of biological therapies for RA, perforations of the lower gastrointestinal tract have become more frequently reported than those of the upper tract. Tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor, has been identified as a potential agent that increases the risk of lower GIPs [3, 5]. Moreover, further studies have found that steroids and NSAID treatment may also increase the risk of lower GIPs [6, 7].

More recently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of RA and other autoimmune disorders, such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and psoriasis. These immunosuppressive medications target the JAK family of enzymes, thereby interfering with downstream proinflammatory pathways [8]. Tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for RA treatment, followed by upadacitinib and baricitinib. In pivotal clinical trials of JAK inhibitors, few cases of GIPs were first observed up to 24 weeks of treatment [9, 10]. Subsequent long-term extension studies and pooled analyses of randomized clinical trials investigated GIPs as adverse events of special interest and found additional cases [11-14]. As the JAK-STAT axis is affected by IL-6 signaling pathway and IL-6 inhibitors have been shown to be associated with GIPs, it was hypothesized that they might share a mutual biological mechanism [15]. However, cumulative exposure to biological treatments, steroids, and NSAIDs, as well as gastrointestinal comorbidities (e.g., peptic ulcer and diverticular disease) may also account for the increased risk. Consequently, these findings have led the FDA to recommend cautious use of JAK inhibitors in patients at risk for GIP, such as patients with a history of diverticulitis or peptic ulcer disease, and in patients receiving concurrent treatment with steroids or NSAIDs [16].

Since GIPs are a potentially rare but serious adverse event that may occur after a prolonged duration of treatment, large-scale postmarketing databases with a long-term follow-up are required to study this association, as previously exemplified in multiple cases [17-19]. For this purpose, we utilized the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS), the largest global post-marketing surveillance program, facilitating post-marketing safety signal detection of rare adverse events. Herein, we aimed to investigate the association between GIPs and JAK inhibitor treatment compared with biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) and to characterize their safety reports.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Data Source and Study Design

An observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study was designed using the FAERS, a global post-marketing safety surveillance program that includes voluntary and mandatory adverse events reports submitted by healthcare professionals, consumers, and manufacturers. The study design and methodology adhered to the READUS-PV guidelines for reporting disproportionality analyses (Table S1) [20, 21]. The database was screened for individual case safety reports of patients with RA who reported JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, upadacitinib, or baricitinib) or bDMARDs (TNF inhibitors, rituximab, and abatacept) as the primary suspects for a given adverse event between July 1, 2014, and September 30, 2023. Patients below 18 years of age and those with a cancer diagnosis or oncological treatment were excluded. Likewise, due to the known association of IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab) with GIPs [3], they were not included in the comparator group or the exposure group when reported concurrent with JAK inhibitors. In a separate analysis, we assessed the reporting of GIPs following IL-6 inhibitors, which served as a validation for our methodology due to their known association with this potential adverse event. In case several reports of the same safety event were available, only the latest case version was retained, as recommended by the FDA. To eliminate suspected duplicate reports with different case numbers (i.e., the same report submitted by different reporters), we identified and excluded reports of the same drug-adverse event pair with identical values in four additional key fields: age, sex, event date, and country of occurrence, as previously described [18, 22].

Adverse events in the FAERS are coded at the “Preferred-term” (PT) level of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) classification. To define the study endpoint, that is gastrointestinal perforations, PTs were listed and safety reports including these terms were defined as an outcome event (Table S2). To perform sub-analysis by anatomic location, terms describing events in the gastrointestinal tract proximal to the duodenojejunal flexure were categorized into upper GIP, and reports of events distal to the duodenojejunal flexure were categorized into lower GIP. Nonspecific terms or those lacking an anatomic description were categorized as unspecified GIP. Notably, some events were originally coded as upper or lower GIP with the corresponding PT by the reporters.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

We performed a disproportionality analysis using the reporting odds ratio (ROR), a well-validated measure to detect signals of disproportionate reporting in post-marketing passive surveillance databases [23, 24]. The ROR evaluates whether a drug-adverse event pair is reported higher-than-expected. The expected number is the occurrence of the adverse event drugs in the reference group. In this study, the exposure group included reports of tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib. We used a restricted comparator group consisting of the abovementioned bDMARDs, also known as “disproportionality by therapeutic area,” thereby mitigating potential indication bias [25]. RORs were adjusted (adj.ROR) for age, sex, and concurrent treatment with steroids or NSAIDs using a multivariable logistic regression model. Missing age data were handled with the median imputation method. As none of the interaction terms was statistically significant, they were not included in the final model. A lower bound of the adj.ROR 95% confidence interval (CI) greater than one was used as the threshold for signal detection [24]. For sub-analysis of specific JAK inhibitors, we assessed each agent against the bDMARDs comparator. Data processing and statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

3 Results

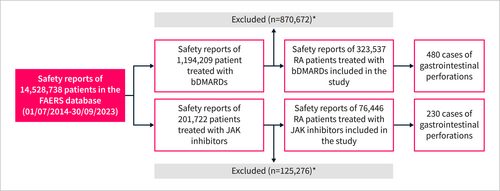

The FAERS database included Safety reports of 14,528,738 patients between July 1, 2014, and September 30, 2023. After applying exclusion criteria, the study included safety reports of 76,446 RA patients who were treated with JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, n = 52,365; upadacitinib, n = 21,856; baricitinib, n = 2225) and 323,537 RA patients who were treated with bDMARDs (TNF inhibitors [n = 273,480], abatacept [n = 38,544], rituximab [n = 11,513]) (Figure 1). The mean age was 61 (±12) and 59 (±13), and the female proportion was 81.9% and 81.1%, respectively (Table 1). Treatment with steroids or NSAIDs concurrent with JAK inhibitors was reported by 14.9% and 13.7% of the patients, respectively. Most NSAIDs were nonselective in both the JAK inhibitor and bDMARD groups (98.0% and 96.9%, respectively). The most frequently reported steroid was prednisone (67.3% and 61.8%, respectively), followed by prednisolone (14.1% and 12.9%) and methylprednisolone (6.6% and 16.9%) (Table S3). Reports of both JAK inhibitors and bDMARDs were primarily from the Americas (91.6% and 88.5%, respectively), especially the United States (79.1% and 68.1%). Safety reports were submitted by healthcare professionals in 43.7% of the JAK inhibitor cases and 49.7% of the bDMARD cases. The absolute number of safety reports of JAK inhibitors consistently increased from 2014 to 2023, while the number of bDMARDs reports was roughly stable (Table 1).

Study flowchart. * Inclusion criteria: RA indication, age ≥ 18 years, drugs reported as the primary suspects of the adverse event. Exclusion criteria: cancer diagnosis/treatment, suspected duplications, reports with tocilizumab as the primary suspect or concomitant drug. bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; JAK, Janus kinase; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

| JAK inhibitors (n = 76,446) | bDMARDs (n = 323,537) | |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting regiona | ||

| Americas | 66,478/72,544 (91.6) | 274,133/309,921 (88.5) |

| Europe | 2913/72,544 (4.0) | 24,842/309,921 (8.0) |

| Asia | 2779/72,544 (3.8) | 8503/309,921 (2.7) |

| Australia | 304/72,544 (0.4) | 1564/309,921 (0.5) |

| Africa | 70/72,544 (0.1) | 879/309,921 (0.3) |

| Reporter | ||

| Health-professional | 31,959/73,195 (43.7) | 156,164/314,008 (49.7) |

| Consumer/Lawyer/Other | 41,236/73,195 (56.3) | 157,844/314,008 (50.3) |

| Reporting year | ||

| 2014b–2015 | 2857/76,446 (3.7) | 52,842/323,537 (16.3) |

| 2016–2017 | 8435/76,446 (11.0) | 89,543/323,537 (27.7) |

| 2018–2019 | 13,435/76,446 (17.6) | 65,540/323,537 (20.3) |

| 2020–2021 | 22,678/76,446 (29.7) | 52,636/323,537 (16.3) |

| 2022–2023b | 29,041/76,446 (38.0) | 62,976/323,537 (19.5) |

| Agec, years | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 61 (± 12) | 59 (± 13) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 61,494/75,047 (81.9) | 251,639/310,415 (81.1) |

| Male | 13,553/75,047 (18.1) | 58,776/310,415 (18.9) |

| Concomitant steroids/NSAIDs used | 11,368/76,446 (14.9) | 44,171/323,537 (13.7) |

| Nonselective NSAIDs | 4383/76,446 (5.7%) | 15,387/323,537 (4.8%) |

| COX-2 selective NSAIDs | 91/76,446 (0.1%) | 499/323,537 (0.2%) |

| Steroids | 8763/76,446 (11.5%) | 35,441/323,537 (11.0%) |

- Note: All values are n/N (%) unless otherwise indicated; the denominator indicates the actual number of reports without missing data.

- Abbreviations: bDMARDs, biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD, standard deviation.

- a 79.1% and 68.1% of the patients treated with JAK inhibitors and bDMARDs, respectively, were from the United States.

- b Only cases reported between July 1, 2014, and September 30, 2023 were included in the study.

- c Age data were missing in 14,989 (19.6%) patients in the JAK inhibitors group and 106,122 (32.8%) patients in the bDMARDs group.

- d Total number of patients who reported concomitant treatment with NSAIDs or steroids at the time of adverse event occurrence.

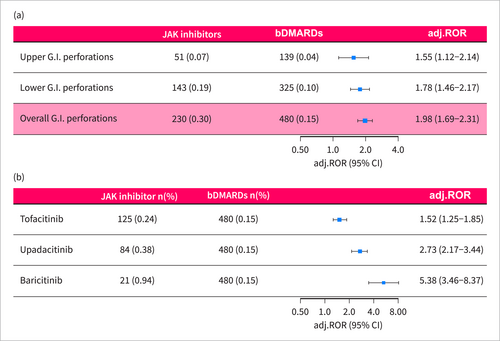

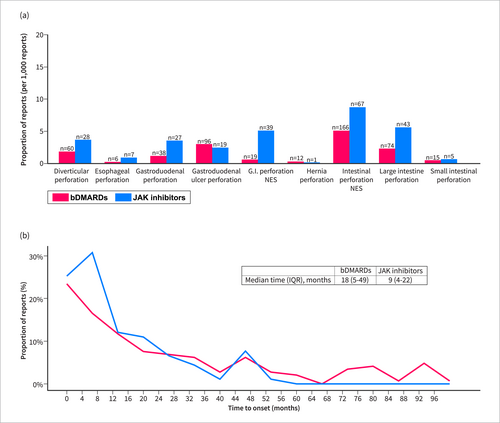

GIPs were reported in 230 out of 76,446 individual case safety reports of JAK inhibitors and 480 out of 323,537 individual case safety reports of bDMARDs. Gastrointestinal perforations were reported two-fold more frequently following JAK inhibitors than bDMARDs (adj.ROR = 1.98 [1.69–2.31]) after adjustment for age, sex, and concurrent use of steroids or NSAIDs (Figure 2a). The median time from treatment initiation to gastrointestinal perforation was 9 (IQR: 4–22) months for JAK inhibitors and 18 (5–49) for bDMARDs (Figure 3b). 32.2% (n = 74/230) of the patients who reported JAK inhibitor-related gastrointestinal perforation were treated concomitantly with steroids or NSAIDs, compared to 14.8% (n = 11,295/76,217) among those who reported other JAK inhibitor-related safety events (p < 0.001). In the multivariable model, treatment with steroids or NSAIDs concurrent to JAK inhibitors or bDMARDs was significantly associated with increased reporting of GIPs (adj.ROR = 2.82 [2.41–3.31]) after adjustment for the excess risk of JAK inhibitor treatment versus bDMARDs. Most of the tofacitinib-related gastrointestinal perforations (GIPs) occurred at doses of either 5 mg or 11 mg in the extended-release tablets. A small proportion (4.7%, n = 5) of GIP cases were reported with the 10 mg dose, which was slightly higher than the proportion of 10 mg treatment in non-GIP reports of JAK inhibitors (1.8%, n = 844, p = 0.049) (Table S3). For upadacitinib, GIPs were primarily reported at a 15 mg dose (95.7%), while baricitinib-related GIPs were reported with both the 2 and 4 mg doses (42.9% and 57.1%, respectively), similar to the distribution seen in non-GIP reports of JAK inhibitors. The overall reported case fatality rate was 12.5% (9.6% after JAK inhibitors and 12.6% after bDMARDs) and all cases were reported as serious medical events, namely resulting in hospitalization, death, life-threatening or other serious medical events.

Disproportionality analysis of JAK inhibitor-related gastrointestinal perforations. Disproportionality analysis of GIPs reporting following treatment with JAK inhibitors in RA patients compared with bDMARDs (TNF-α inhibitors, rituximab, and abatacept). RORs were adjusted for age, sex, and concurrent treatment with steroids or NSAIDs. (a) GIPs were stratified to perforations of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. (b) GIPs were stratified to JAK inhibitor type. adj.ROR, adjusted reporting odds ratio; bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GIP, gastrointestinal perforation.

Major sub-categories of gastrointestinal perforations and time to onset from treatment initiation. (a) Major sub-categories of gastrointestinal perforations. (b) Time to onset from treatment initiation of JAK inhibitors and bDMARDs to gastrointestinal perforation occurrence.

JAK inhibitor treatment was associated with increased reporting of perforations of both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract (adj.ROR = 1.55 [1.12–2.14] and adj.ROR = 1.78 [1.46–2.17], respectively) (Figure 2a). While both were statistically significant, the absolute number of safety reports of lower GIPs (n = 143) was higher than that of upper GIPs (n = 51). Of note, 36 (15.7%) reports of GIPs did not specify anatomic location. Concerning the pathological mechanism, 12.2% (n = 28) of the gastrointestinal perforation cases were reported as diverticular perforation, 8.3% (n = 19) as gastroduodenal ulcer perforation, and 46.1% (n = 106) were reported as general terms—“intestinal perforation” or “gastrointestinal perforation” (Figure 3a).

When stratified by JAK inhibitor agent, the disproportionate reporting signal was significant across all JAK inhibitors: tofacitinib (n = 125, adj.ROR = 1.52 [1.25–1.85]), upadacitinib (n = 84, adj.ROR = 2.73 [2.17–3.44]), and baricitinib (n = 21, adj.ROR = 5.38 [3.46–8.37]) (Figure 2b).

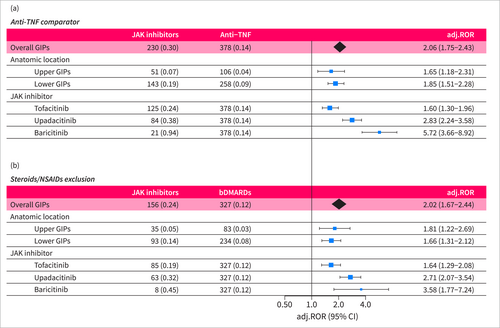

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, we stratified the analysis by reporter occupation due to the considerable proportion of reports from non-healthcare providers. A significantly increased reporting of GIPs was observed in both healthcare provider and non-healthcare provider reports (adj. ROR = 2.94 [2.37–3.65] and adj. ROR = 1.35 [1.06–1.70], respectively) with no statistically significant difference between the groups (p = 0.58). Second, we restricted the comparator group to anti-TNF medications. In this analysis, the safety signal of GIPs retained statistical significance (adj. ROR = 2.06 [1.75–2.43]), also when assessing different JAK inhibitors and anatomic locations separately (Figure 4a). Third, excluding patients with concomitant use of steroids or NSAIDs also yielded consistent results (adj. ROR = 2.02 [1.67–2.44], Figure 4b).

Sensitivity analyses of disproportionality analysis. Sensitivity analyses of the main disproportionality analysis assessing GIPs reporting following treatment with JAK inhibitors in RA patients. (a) Restriction of the comparator group to anti-TNF medications. (b) Exclusion of patients who reported concomitant treatment with NSAIDs or steroids. adj.ROR, adjusted reporting odds ratio; bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GIP, gastrointestinal perforation; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

We further assessed GIPs reporting following treatment with IL-6 inhibitors. Individual case safety reports of 22,789 tocilizumab recipients were identified, 503 of them reporting GIPs. As expected, tocilizumab treatment was associated with a statistically significant increased reporting of GIPs (adj.ROR = 12.61 [11.09–14.33]) compared to other bDMARDs. Likewise, we identified 7014 individual case safety reports of the IL-6 inhibitor sarilumab, of which 18 were of GIPs, also resulting in a significant over-reporting (adj.ROR = 1.94 [1.21–3.11]).

4 Discussion

In this global pharmacovigilance study, we provide the largest analysis to date of GIPs following treatment with JAK inhibitors. GIPs were reported two-fold more frequently in patients treated with JAK inhibitors compared with bDMARDs (anti-TNF, abatacept, and rituximab). The disproportionate reporting signal was significant across all JAK inhibitors and in both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts. Furthermore, concomitant treatment with steroids or NSAIDs was associated with an increased reporting of GIPs. Although causality cannot be established using the FAERS, these findings should increase clinicians' awareness of this potentially late-onset serious adverse event, particularly among patients with risk factors.

While cardiovascular safety and malignancy risk have been a recent concern for regulators and clinicians, the gastrointestinal toxicity of JAK inhibitors has received limited attention. GIPs were first reported in a small number of patients in pivotal clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in RA. The ORAL Start and SELECT-BEYOND studies reported two cases of GIPs, one following treatment with tofacitinib and the other following upadacitinib [9, 10]. However, these adverse events were not observed in other phase 3 clinical trials [26-29]. Subsequently, the long-term extension studies of tofacitinib, the ORAL Surveillance and ORAL Sequel, reported 14 and 23 cases, respectively [11, 12]. The estimated incidence rate in these studies ranged between 0.1 and 0.2 per 100 patient-years, but they were underpowered to demonstrate a statistically significant increased risk. Furthermore, a pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials of baricitinib found nine cases of GIPs [14]. Observational data to date mainly consist of two population-based studies. The first study found an incidence of 0.86 per 1000 treatment years following tofacitinib treatment in RA, although it was based on only two cases [3]. The second observed an incidence rate of 2.1 per 1000 person-years in a national French health data system, slightly higher than that reported in clinical trials, but did not find a statistically significant increased risk compared to adalimumab [30]. Of note, the study included a large proportion of rheumatologic diseases other than RA, which may carry a lower baseline risk of GIP. In the FAERS repository analyzed herein, 230 cases of JAK inhibitor-associated GIPs were reported. The safety signal was robust and statistically significant after adjustment, across different JAK inhibitors and anatomical sites, and in several sensitivity analyses. Although additional prospective studies are required to assess the strength of the association between JAK inhibitor treatment and GIPs, clinicians should be aware of this potential serious adverse event.

Gastrointestinal perforations are more frequent in RA patients, primarily ascribed to the common use of NSAIDs or steroids [2]. Initially, upper GIPs were the main concern of NSAIDs and steroids use [4] but further studies found an increased risk of lower GIPs as well [6, 7]. Over the years, a decreasing trend of upper GIPs was observed, likely due to prophylaxis with proton pump inhibitors, Helicobacter pylori eradication, and judicious use of NSAIDs. Consequently, lower GIPs became a greater concern, and several biologics were identified as potential drivers, particularly IL-6 inhibitors [2, 19, 31]. Notwithstanding, steroids and NSAIDs use remains a major risk factor overall, as was demonstrated in a large-scale observational study in which 70% of the patients with GIPs received glucocorticoids or had a previous diagnosis of diverticulitis [2]. Correspondingly, in the present study, perforations of the lower gastrointestinal tract were more frequently reported than those of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with concurrent treatment with NSAIDs or steroids significantly increasing the frequency of such reports. Notably, while the absolute number of upper gastrointestinal perforations was lower, they were also significantly over-reported among recipients of JAK inhibitors compared to bDMARDs, and therefore should also be considered for future post-marketing monitoring. Overall, gastrointestinal perforations are likely to be multifactorial; thus, monitoring and cautious use of JAK inhibitors are particularly warranted in patients exposed to NSAIDs or steroids or having a history of diverticulitis.

JAK inhibitors exert pleiotropic effects on the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, each with a distinct selectivity for different JAK family enzymes. This distinct molecular affinity raises the question of whether their safety profiles also differ. Clinical trials reported few cases of GIPs with each of the three JAK inhibitors, although more rarely with upadacitinib, a JAK-1 selective inhibitor [9-14]. In this study, we found a statistically significant increased reporting of GIPs following treatment with all three JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib), suggesting an elevated risk across these agents. While this study did not directly compare JAK inhibitors, baricitinib had the highest disproportionate reporting of GIPs. Given that baricitinib is more selective for JAK-2 and upadacitinib for JAK-1, the potential role of JAK-2 in maintaining gastrointestinal tract wall integrity warrants further research.

Regarding the biological mechanism, the STAT pathway plays a role in maintaining mucosal healing and the integrity of the gastric mucosal barrier, as demonstrated in several studies [32]. One study showed that mice with defective STAT activation developed occult fecal blood and gastric ulceration [33]. Additionally, the JAK-STAT and IL-6 signaling pathways are interconnected, and IL-6 inhibition has been shown to increase the risk of gastrointestinal perforations, further supporting the biological rationale [15]. Apparently, the IL-6 receptor plays a role in the immune response to mucosal surface infections and is important for maintaining the mucosal barrier [7, 31]. In our analysis, both IL-6 inhibitors—tocilizumab and sarilumab—were significantly associated with increased reporting of GIPs, reinforcing the presumed link between IL-6 inhibition and GIPs and validating our study methodology.

As the use of JAK inhibitors continues to expand in the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), there is a current clinical need to assess the risk of GIPs in this population. Clinical trials of JAK inhibitors in IBD patients observed few cases of GIPs. In the OCTAVE trials of tofacitinib induction therapy for ulcerative colitis, one case of GIP occurred in the tofacitinib group and one in the placebo group, whereas none occurred in the maintenance trial [34]. Clinical trials of upadacitinib for Crohn's disease reported four cases of GIP with a 45 mg upadacitinib induction therapy (one during the placebo-controlled period and three in the extended treatment period) and one case was reported in each of the maintenance groups [35]. No cases of GIP were observed in the clinical development program of upadacitinib induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis [36]. As these events are rare and may occur after a long treatment duration, large-scale population-based data have not yet accumulated. On one hand, IBD patients are generally younger and use fewer NSAIDs than RA patients. On the other hand, the presence of colonic inflammation itself increases their risk of GIPs, as does their increased use of steroids and more frequent endoscopic tests [37]. Therefore, further research and careful surveillance are warranted in IBD patients.

5 Limitations

Several limitations of this pharmacovigilance study should be acknowledged. First, because the inherent passive nature of the FAERS causality cannot be inferred, the study findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. Second, the study provides absolute numbers but not a true incidence, which cannot be calculated using the FAERS since the number of patients exposed to the drugs is unknown. However, recent studies assessing prescribing patterns of different RA drugs reported that bDMARDs are prescribed more often than JAK inhibitors [38], thereby supporting and even possibly enhancing the validity of our findings. Third, granular data on patients' characteristics and medical history are lacking in the FAERS. Particularly, reliable data on GIP risk factors such as diverticular and peptic ulcer diseases, and concomitant use of protective medications such as proton pump inhibitors, are not available. To mitigate potential confounders, we used a restricted comparator group of other bDMARDs, which represents a similar patient population to JAK inhibitor recipients, and excluded patients who reported treatment with tocilizumab or oncological medications. Furthermore, RORs were adjusted for age, sex, and concomitant use of steroids or NSAIDs using a multivariable logistic regression model. However, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Fourth, channeling bias is another source of concern since JAK inhibitors are commonly used for more advanced disease or after the failure of other bDMARDs. Fifth, reporting bias is a recognized limitation of passive surveillance databases. As JAK inhibitors are a novel class of immunosuppressants, adverse events might be reported more frequently for these drugs compared with older bDMARDs according to the Weber effect [39]. However, more recent studies indicated that most of the modern adverse events reported to the FAERS do not follow the pattern described by Weber [40]. Reporting bias may also contribute to an underreporting of concomitant medications, particularly leading to an underestimation of NSAID and steroid use. Finally, the FAERS reflects real-world settings and provides an opportunity for studying rare adverse events due to its global spread that allows a remarkably large sample size. However, the vast majority of the safety reports included in the current study were from the USA. Therefore, further studies of other geographic regions that might have different prescribing patterns for JAK inhibitors and concomitant medications, as well as distinct comorbidity profiles are required. Notably, studies of disproportionality analysis demonstrated striking accuracy and have been pivotal in identifying the toxicities of immunosuppressive medications [24, 25, 41, 42].

6 Conclusion

In this global pharmacovigilance study, JAK inhibitors were significantly associated with an increased reporting of GIP compared with bDMARDs in RA patients. The disproportionate reporting signal was significant for perforations of both the upper and lower parts of the gastrointestinal tract and consistent across all JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib). Concurrent treatment with steroids or NSAIDs increased GIP reporting. Although causality cannot be established, these findings should increase clinicians' awareness of this late-onset serious toxicity, particularly among patients with risk factors. Careful surveillance is warranted in other populations such as IBD patients.

Author Contributions

Adam Goldman: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing–original draft, project administration, formal analysis. Emanuel Raschi: writing–review & editing, validation, supervision, methodology. Amit Druyan: writing–review & editing, conceptualization. Kassem Sharif: writing–review & editing. Adi Lahat: writing–review & editing. Ilan Ben-Zvi: writing–review & editing, conceptualization. Shomron Ben-Horin: supervision, writing–review & editing, conceptualization, writing–original draft, validation.

Ethics Statement

Because the FAERS is a publicly available and anonymized database, institutional review board approval and informed consent were waived.

Conflicts of Interest

Prof. Shomron Ben-Horin has received Advisory board and/or consulting fees from Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Celltrion, Pfizer, GSK, Ferring, Novartis, Roche, Gilead, NeoPharm, Predicta Med, Galmed, Medial Earlysign, and Eli Lilly, holds stocks/options in Galmed, Evinature, PredictaMed and Alma Therapeutics and received research support from Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Celltrion, Pfizer, Medtronic & Galmed.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Quarterly Data Files, at https://fis.fda.gov/extensions/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html.