Feasibility assessment for practical continuous variable quantum key distribution over the satellite-to-Earth channel

Funding information: Defence Science and Technology Group

Summary

Currently, quantum key distribution (QKD) using continuous variable (CV) technology has only been demonstrated over short-range terrestrial links. Here, we attempt to answer whether CV-QKD over the much longer satellite-to-Earth channel is feasible. To this end, we first review the concepts and technologies that will enable CV-QKD over the satellite-to-Earth channels. We then consider, in the infinite key limit, the simplest-to-deploy QKD protocols, the coherent state (CS) QKD protocol with homodyne detection and the CS-QKD protocol with heterodyne detection. We then focus on the CS-QKD protocol with heterodyne detection in the pragmatic setting of finite keys, where complete security against general attacks is known. We pay particular attention to the relevant noise terms in the satellite-to-Earth channel and their impact on the secret key rates. In system set-ups where diffraction dominates losses, we find that the main components of the total excess noise are the intensity fluctuations due to scintillation, and the time-of-arrival fluctuations between signal and local oscillator. We conclude that for a wide range of pragmatic system models, CS-QKD with information-theoretic security in the satellite-to-Earth channel is feasible.

1 INTRODUCTION

Quantum key distribution (QKD) provides information-theoretic secure key distribution between two parties. Local data sent by a sender, Alice, is encrypted using a key that is guaranteed by quantum mechanics to be securely shared only with the receiving party, Bob. QKD is mainly implemented using optical technology, making it ideal for secure key distribution over a high bandwidth free-space optical (FSO) link.

In discrete variable (DV) QKD applied over fiber the quantum information is usually encoded in a DV of a single photon (eg, time-bin qubit), with a secure range of order 400 km.1 However, recently, DV-based QKD using polarization as the DV was demonstrated in a free-space satellite-to-ground channel up to a distance of 1200 km.2 In Reference 2, a quantum link was established from the low-Earth-orbit (LEO) Micius satellite to the Xinglong ground station. This exciting development is a major step towards realizing global scale secure quantum communications using low-orbit satellites. Indeed, quantum communication through satellite channels is anticipated to be one of the core technologies enabling the so-called quantum internet.3

However, it is uncertain whether DV or continuous variable (CV) multiphoton technologies (or a combination of CV-DV) will prevail in FSO quantum communication. CV protocols have the advantage of high-rate, efficient, and cost-effective detection (using homodyne and heterodyne detectors) in comparison to the sophisticated and expensive single-photon detectors used for DV protocols. CV-QKD is also perhaps more compatible with current classical wireless communications technologies. Initially, CV-QKD was proposed with discrete and Gaussian encoding of squeezed states.4-7 Thereafter, Gaussian-modulated CV-QKD with coherent states was soon developed.8-10

The simplest-to-deploy CV-QKD protocols are the GG02 protocol introduced in 2002 by Grosshans and Grangier using a homodyne detector,9, 10 and its heterodyne variant (“the no-switching” protocol).11 These both involve preparation of a coherent state (CS) using Gaussian modulation.7, 8 More specifically, the quadratures X and P of the CS are randomly modulated according to a Gaussian distribution.8 In this article, we refer to GG02 and the no-switching protocol as the CS-Hom protocol and CS-Het protocol, respectively. We state them as the CS-QKD protocols when we refer to them collectively. The CS-QKD protocols have been successfully deployed in fiber with nonzero quantum keys distributed over distances of order 100 km.8, 12, 13

The question we address in this work is whether the simplest-to-deploy CV-QKD protocols, namely the CS-QKD protocols, will be viable in a real-world LEO satellite-to-Earth channel. Although extensive theoretical work on CV-QKD through terrestrial FSO channels has been done in recent years, for example, References 14-21, the only real-world FSO deployment of any CV-QKD protocol has been over the short distance of 460 m.22 The larger losses due to diffraction over the much longer satellite-to-Earth channel (as well as disparate turbulence effects),23 render any extrapolation of the results in Reference 22 far from obvious. This is compounded by the fact that Reference 22 deployed a different form of CV-QKD, namely, a CS unidimensional CV-QKD protocol.

Our contributions in this work can be summarized as follows. We identify the most important factors contributing to the total excess noise of the CS-QKD protocols in the satellite-to-Earth channel. We pay particular attention to the noise contributions arising from scintillation and contributions arising from time-of-arrival fluctuations between the transmitted local oscillator (LO) and the quantum signal. Using our determination of the total excess noise we then consider a lower bound on the secure key rates anticipated for the CS-QKD protocols deployed over the satellite-to-Earth channel. We will consider secure rates in the asymptotic signaling limit for both of the CS-QKD protocols, and in the finite key limit for the CS-Het protocol.1

The rest of this work is as follows. In Section 2, we review the security models required for calculating the secret key rate of the CS-QKD protocols in a lossy channel. In Section 3, we introduce the system model of the CS-QKD protocols in the satellite-to-Earth channel, and review well-known contributions to the total excess noise from the channel and detectors. In Section 4, we simulate the relative intensity fluctuations and time-of-arrival fluctuations. In Section 5, we investigate the impact on the secret key rate of each noise term. In Section 6, we discuss the security of the CS-QKD protocols in the satellite-to-Earth channel and discuss alternative protocols. In Section 7, we discuss our work in the context of other CV-QKD protocols. Finally, we conclude and summarize our findings in Section 8.

2 SECURITY ANALYSIS OF CS-QKD IN A LOSSY CHANNEL

In our security model of the CS-QKD protocols in the satellite-to-Earth channel, we assume the eavesdropper Eve has full access to the quantum channel and performs the most general (coherent) attack. The general attack is when Eve prepares an optimal global ancilla state, which may not necessarily be separable. Eve can prepare any ancillary states to interact with the signal states and make measurements. In particular, Eve can have access to a quantum memory, which can store the signal states until she learns information during the classical postprocessing. In our security model, we perform the analysis in the entanglement based version of the CS-QKD protocols, even though in deployment we will assume the equivalent prepare and measure schemes.24, 25 In deployment, it is straightforward to convert measurements from one scheme to the other.24

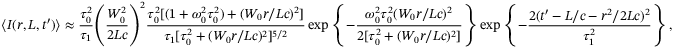

Information-theoretic security against the general attack for the CS-QKD protocols was proven in the asymptotic limit where an infinite key was assumed.26 The general attack was proven to reduce to the collective attack using the de Finetti representation theorem for infinite dimensions.27 However, in practice, we need to consider the secret key rate in the finite limit which can only be  -secure, where

-secure, where  is the probability of failure. Information-theoretic security of the CS-Hom protocol in the finite regime is still an open question. However, by exploiting a new Gaussian de Finetti reduction method, a composable security proof against general attacks for the CS-Het protocol was recently proven.28

is the probability of failure. Information-theoretic security of the CS-Hom protocol in the finite regime is still an open question. However, by exploiting a new Gaussian de Finetti reduction method, a composable security proof against general attacks for the CS-Het protocol was recently proven.28

2.1 Asymptotic limit

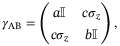

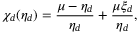

()

() is the unity matrix and

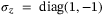

is the unity matrix and  is the Pauli matrix. For the Gaussian modulated CS-QKD protocols, the coefficients of the covariance matrix are

is the Pauli matrix. For the Gaussian modulated CS-QKD protocols, the coefficients of the covariance matrix are

()

() is the detector quantum efficiency.2The CS-Hom and CS-Het protocols correspond to

is the detector quantum efficiency.2The CS-Hom and CS-Het protocols correspond to  and

and  , respectively. The term

, respectively. The term  is defined as all noise terms other than vacuum noise, expressed in vacuum units. In the literature it is common to distinguish between noise,

is defined as all noise terms other than vacuum noise, expressed in vacuum units. In the literature it is common to distinguish between noise,  , arising from the detector and noise,

, arising from the detector and noise,  , arising from the channel transmission where,29

, arising from the channel transmission where,29

()

() is given by

is given by

()

() is the channel excess noise from various sources and (1 − T)/T is due to channel loss.

is the channel excess noise from various sources and (1 − T)/T is due to channel loss.  is given by

is given by

()

() is the detector excess noise and

is the detector excess noise and  is noise due to detector losses.

is noise due to detector losses. ()

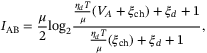

() is the reconciliation efficiency, and SBE is the upper bound to the Holevo information between Eve and Bob. In this work we will only consider reverse reconciliation where Bob sends correction information to Alice who corrects the bit values in the key (derived from her quadrature measurement).32 The mutual information IAB for the CS-QKD protocol is given by

is the reconciliation efficiency, and SBE is the upper bound to the Holevo information between Eve and Bob. In this work we will only consider reverse reconciliation where Bob sends correction information to Alice who corrects the bit values in the key (derived from her quadrature measurement).32 The mutual information IAB for the CS-QKD protocol is given by

()

() ,

,  and

and  . Note also, the mutual information becomes

. Note also, the mutual information becomes

()

() , as expected.

, as expected. . Consequently, in the Holevo information shared between Eve and Bob in (9), we only consider

. Consequently, in the Holevo information shared between Eve and Bob in (9), we only consider  . Eve's information after Bob's measurement is the upper bound on the Holevo information,

. Eve's information after Bob's measurement is the upper bound on the Holevo information,

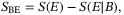

()

() ()

() and

and  are the symplectic eigenvalues of the covariance matrix

are the symplectic eigenvalues of the covariance matrix  . For CS-QKD protocols, these are given by Reference 29

. For CS-QKD protocols, these are given by Reference 29

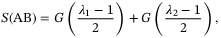

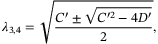

()

() ()

() are the symplectic eigenvalues of the conditional covariance matrix characterizing the state after Bob's measurement. The eigenvalues

are the symplectic eigenvalues of the conditional covariance matrix characterizing the state after Bob's measurement. The eigenvalues  are given by,

are given by,

()

() ()

() ()

() for both protocols. Using (6) and (10) to (15), it is then straightforward to calculate the secret key rate in the asymptotic limit.

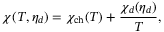

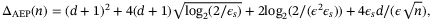

for both protocols. Using (6) and (10) to (15), it is then straightforward to calculate the secret key rate in the asymptotic limit.2.2 Finite key size effects

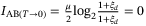

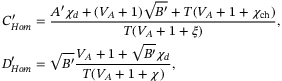

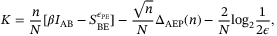

-security that was first introduced in References 35, 36 and extended to general attacks in References 28, 37-39. In the infinite limit, the knowledge of the relevant parameters are exact, but in the finite limit, the parameters are estimated with a finite precision. This precision is related to the probability

-security that was first introduced in References 35, 36 and extended to general attacks in References 28, 37-39. In the infinite limit, the knowledge of the relevant parameters are exact, but in the finite limit, the parameters are estimated with a finite precision. This precision is related to the probability  the true values are not inside the confidence interval calculated from the parameter estimation procedure.35, 36 In the finite limit, the secret key rate in bits/pulse is given by References 37,38

the true values are not inside the confidence interval calculated from the parameter estimation procedure.35, 36 In the finite limit, the secret key rate in bits/pulse is given by References 37,38

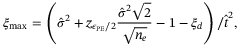

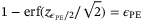

()

() is the total failure probability of the protocol,

is the total failure probability of the protocol,  is the upper bound of the Holevo information taking into consideration the finite precision of the parameter estimation, N is the total number of symbols sent, and n = N − ne, where ne is the number of symbols used for parameter estimation.

is the upper bound of the Holevo information taking into consideration the finite precision of the parameter estimation, N is the total number of symbols sent, and n = N − ne, where ne is the number of symbols used for parameter estimation.  is given by References 37, 38

is given by References 37, 38

()

() is a smoothing parameter corresponding to the speed of convergence of the smooth min-entropy. In the finite-size regime, one is limited to

is a smoothing parameter corresponding to the speed of convergence of the smooth min-entropy. In the finite-size regime, one is limited to  -security where

-security where  , where

, where  is the failure probability of the privacy amplification procedure, and

is the failure probability of the privacy amplification procedure, and  is the failure probability of the error correction. The parameters

is the failure probability of the error correction. The parameters  and

and  can be optimized computationally.35

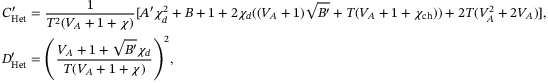

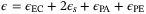

can be optimized computationally.35 , the previous covariance matrix (2) for Alice and Bob becomes,35, 36

, the previous covariance matrix (2) for Alice and Bob becomes,35, 36

()

() are the minimum and maximum values of T and

are the minimum and maximum values of T and  , respectively.

, respectively. can be calculated from known distributions of the estimators5

can be calculated from known distributions of the estimators5 and

and  to obtain the lower value of the T interval given by References 35, 36,

to obtain the lower value of the T interval given by References 35, 36,

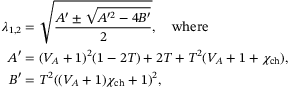

()

() interval given by,

interval given by,

()

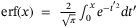

() satisfies

satisfies  and erf(x) is the error function defined as

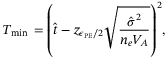

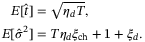

and erf(x) is the error function defined as  . From a theoretical perspective and what we do in this work, we can set the expectation values of the estimators to

. From a theoretical perspective and what we do in this work, we can set the expectation values of the estimators to

()

()Using these values, we can compute Tmin and  . To determine

. To determine  in (16) for the CS-Het protocol, we use these values in Equations (9)-(13) and (15) (ie, setting T = Tmin and

in (16) for the CS-Het protocol, we use these values in Equations (9)-(13) and (15) (ie, setting T = Tmin and  in Equations (3)-(5)). The mutual information IAB in (16) is calculated as done before in (7) using T and

in Equations (3)-(5)). The mutual information IAB in (16) is calculated as done before in (7) using T and  . Putting all this together, to calculate the secret key rate with finite size effects in (16), we make use of the aforementioned quantities

. Putting all this together, to calculate the secret key rate with finite size effects in (16), we make use of the aforementioned quantities  , IAB, and

, IAB, and  in (17).

in (17).

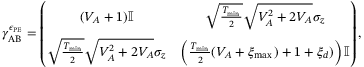

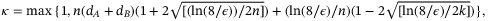

-secure against general attacks with

-secure against general attacks with  , where28

, where28

()

() and thus

and thus  . We choose

. We choose  and number of symbols used for parameter estimation6 ne = n = 1012 which can be obtained in minutes for a source pulse rate of 100 MHz. To obtain the secret key rate under general attacks, it is enough to analyze the security against Gaussian collective attacks with

and number of symbols used for parameter estimation6 ne = n = 1012 which can be obtained in minutes for a source pulse rate of 100 MHz. To obtain the secret key rate under general attacks, it is enough to analyze the security against Gaussian collective attacks with  and

and  .28

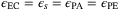

.283 SATELLITE-TO-EARTH CS-QKD

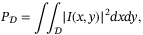

We present our system model in Figure 1. Essentially, a Gaussian modulated CS is prepared on the satellite (Alice) and measured at the ground station (Bob) using homodyne or heterodyne detection. At Alice's location in a LEO satellite at altitude H, a strong laser source generates a CS which is divided by an asymmetrical beamsplitter into the LO and the signal path. The laser source generates pulses at central frequency  of width

of width  and a repetition rate frep. The laser beam is collimated by a transmitter aperture of diameter DT. The amplitude and phase corresponding to X and P quadratures in the signal path are Gaussian modulated with the Gaussian distribution centered at ⟨X⟩ = ⟨P⟩ = 0 with variance VA.

and a repetition rate frep. The laser beam is collimated by a transmitter aperture of diameter DT. The amplitude and phase corresponding to X and P quadratures in the signal path are Gaussian modulated with the Gaussian distribution centered at ⟨X⟩ = ⟨P⟩ = 0 with variance VA.

. Bob receives the signal and the LO which he uses to perform the homodyne or heterodyne detection. The former is represented by a XB quadrature measurement (blue), and the latter by two balanced beamsplitters (purple) and two quadrature measurements (blue XB and purple PB). The heterodyne/homodyne detector efficiency is

. Bob receives the signal and the LO which he uses to perform the homodyne or heterodyne detection. The former is represented by a XB quadrature measurement (blue), and the latter by two balanced beamsplitters (purple) and two quadrature measurements (blue XB and purple PB). The heterodyne/homodyne detector efficiency is  and the detector excess noise

and the detector excess noise  . An entirely equivalent EB scheme is available. EB, entanglement based; PM, prepare and measure. CS, coherent state; EB, entanglement based; LO, local oscillator; PM, prepare and measure; QKD, quantum key distribution

. An entirely equivalent EB scheme is available. EB, entanglement based; PM, prepare and measure. CS, coherent state; EB, entanglement based; LO, local oscillator; PM, prepare and measure; QKD, quantum key distributionThe LO is then multiplexed with the signal (in a different polarization mode) and sent to Bob. Both the LO and signal are received by an aperture of diameter DR. Using the LO, Bob monitors the transmissivity T which has a probability density function PDF PAB(T) of the channel. The PDF is integrated up to a maximum possible value of T = Tmax. In general, the form of this PDF is a function of many atmospheric parameters, the transceiver apertures, and the distance between the transceivers. In the uplink (Earth-to-satellite) deep fades in the transmissivity can be anticipated, largely due to beam wander and beam deformation.40 In this work, we adopt settings where the losses in the satellite-to-Earth channel are dominated by diffraction effects alone. That is, we assume the transmissivity is a constant. As we discuss later, reasonable receiver/transmitter apertures render such an assumption reasonable in the downlink channel.7However, it is worth noting here that additional support for a constant transmissivity in the downlink comes from the phase-screen simulations of Reference 41, which show highly peaked transmissivity PDFs.8

In the CS-Hom protocol, Bob randomly chooses to either measure the quadratures X or P with the homodyne detector and later announces to Alice which quadrature he measured. In the CS-Het protocol, Bob measures both X and P using two detectors at the output of a balanced beamsplitter.

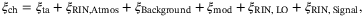

3.1 Noise components

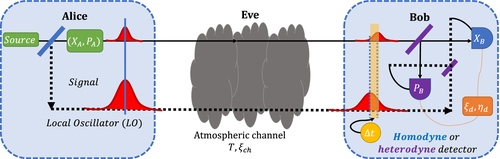

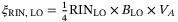

and the detector

and the detector  . Bob's variance9 VB of the quadrature operator in (2) using the definitions in (4) and (5) is

. Bob's variance9 VB of the quadrature operator in (2) using the definitions in (4) and (5) is

()

() ()

() ()

() , relative intensity noise (RIN) due to the atmosphere

, relative intensity noise (RIN) due to the atmosphere  , background noise

, background noise  , modulation noise

, modulation noise  , RIN of the LO

, RIN of the LO  , and RIN of the signal

, and RIN of the signal  . We refer the reader to Table 1 for a description of these noise components. We note that the time-of-arrival fluctuations

. We refer the reader to Table 1 for a description of these noise components. We note that the time-of-arrival fluctuations  and RIN due to the atmosphere,

and RIN due to the atmosphere,  , have not been determined in the satellite-to-Earth channel. An analysis of these two excess noise components is discussed in the following section.

, have not been determined in the satellite-to-Earth channel. An analysis of these two excess noise components is discussed in the following section. of CS-QKD the satellite-to-Earth channel

of CS-QKD the satellite-to-Earth channel |

Channel excess noise component | Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Time-of-arrival fluctuations |  is the noise component due to the differential modifications between signal and LO pulses in the satellite-to-Earth channel. Predictions for this noise component in a terrestrial free-space channel were made in Reference 51, but not for the satellite-to-Earth channel. We will quantify this noise component in the following section. is the noise component due to the differential modifications between signal and LO pulses in the satellite-to-Earth channel. Predictions for this noise component in a terrestrial free-space channel were made in Reference 51, but not for the satellite-to-Earth channel. We will quantify this noise component in the following section. |

|

RIN of LO due to atmosphere |  is the noise component due to the scintillation caused by atmospheric fluctuations. We will quantify this noise in the following section. is the noise component due to the scintillation caused by atmospheric fluctuations. We will quantify this noise in the following section. |

|

RIN of the LO | The noise term  is due to the power fluctuations of the laser before modulation. This noise component is an intrinsic noise that depends on the parameters of the laser.24 is due to the power fluctuations of the laser before modulation. This noise component is an intrinsic noise that depends on the parameters of the laser.24 |

|

Modulation noise | The noise term  is due to the voltage fluctuations in the modulation of the coherent state at Alice.42 The signal generator translates bit information to a voltage which is amplified to drive the modulator.24 The phase of the quadrature is proportional to the applied voltage. Subsequently, the voltage deviation introduced by the signal generator introduces modulation noise. is due to the voltage fluctuations in the modulation of the coherent state at Alice.42 The signal generator translates bit information to a voltage which is amplified to drive the modulator.24 The phase of the quadrature is proportional to the applied voltage. Subsequently, the voltage deviation introduced by the signal generator introduces modulation noise. |

|

Background noise | Part of the channel excess noise for the satellite-to-Earth channel is photon leakage from the background  to the quantum signal and LO.43 to the quantum signal and LO.43 |

|

RIN of the signal | Excess noise due to power fluctuations of the laser translates to the RIN of the signal  . This noise component is proportional to the absolute power variance for a given optical bandwidth of the signal laser.24 In comparison to the RIN of the LO due to the laser, the RIN of the signal is considerably smaller.24 . This noise component is proportional to the absolute power variance for a given optical bandwidth of the signal laser.24 In comparison to the RIN of the LO due to the laser, the RIN of the signal is considerably smaller.24 |

|

Detector excess noise component | |

| vel | Electronic noise | The term vel is electronic noise that is due to other noise sources of the detector including thermal noise and clock jitter affecting the detector. Shot-noise-limited homodyne measurement requires sufficient LO power to reduce the effect of the electronic noise by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio.24, 46 |

|

Analogue-digital converter (ADC) quantization noise |  is due to digitizing the output voltage, required by all CV-QKD systems.24, 44, 45 This noise term can be suppressed by increasing the number of bits. is due to digitizing the output voltage, required by all CV-QKD systems.24, 44, 45 This noise term can be suppressed by increasing the number of bits. |

|

Pulse overlap | The finite response time of the balanced homodyne/heterodyne detector causes an electrical pulse overlap  .47 Large peak powers for shorter pulses can saturate the diodes, causing a nonlinear response. This can be suppressed by ensuring .47 Large peak powers for shorter pulses can saturate the diodes, causing a nonlinear response. This can be suppressed by ensuring  , where , where  is the pulse width. is the pulse width. |

|

LO fluctuations during subtraction | The incomplete subtraction of the output signals by the homodyne/heterodyne detector introduces the noise component  .24, 47 .24, 47 |

|

Leakage noise | Part of the total excess noise is the photon leakage from the LO to the signal when the signal is multiplexed with the LO.46, 47 This term largely depends on the system design. However, in the polarization-frequency-multiplexing scheme, this is, assumed negligible.48 |

- Abbreviations: CS, coherent state; CV, continuous variable; LO, local oscillator; QKD, quantum key distribution; RIN, relative intensity noise.

()

() , detector overlap

, detector overlap  , LO subtraction noise

, LO subtraction noise  , and LO-to-signal leakage

, and LO-to-signal leakage  . We refer the reader to Table 1 for a fuller description of these noise components.

. We refer the reader to Table 1 for a fuller description of these noise components.4 NOISE SIMULATIONS

In the following section, we use the atmospheric channel to determine the channel excess noise contributions from the intensity fluctuations of the LO and the time-of-arrival fluctuations between the LO and signal. Typical values from the literature of each noise contribution (as well as our calculations) are summarized in Table 2.

| Parameter | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Channel excess noise | 0.0186;0.0126 | ||

|

Time-of-arrival fluctuations | 0.006 | This article | |

|

RIN of LO due to atmosphere | 0.01;0.004 | This article | |

|

Relative intensity noise of LO | 0.0018 | 24 | |

|

Modulation noise | 0.0005 | 42 | |

|

Background noise | 0.0002 | 43 | |

|

Relative intensity noise of signal | <0.0001 | 24 | |

|

Detector noise | 0.0133 | ||

| vel | Electronic noise | 0.013 | 46, 47 | |

|

Analogue-digital converter noise | 0.0002 | 44, 45 | |

|

Detector overlap | <0.0001 | 47 | |

|

LO subtraction noise | <0.0001 | 24, 47 | |

|

LO to signal leakage | <0.0001 | 46-48 |

- Abbreviations: ADC, analogue-digital converter; CS, coherent state; LO, local oscillator; QKD, quantum key distribution; RIN, relative intensity noise.

4.1 Relative intensity—LO

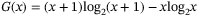

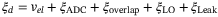

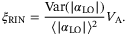

()

() is the coherent amplitude and

is the coherent amplitude and  is the phase of the quadrature measurement. It is clear that oscillations in the amplitude

is the phase of the quadrature measurement. It is clear that oscillations in the amplitude  of the LO will introduce an additional excess noise to the protocol. Assuming for simplicity we intend to measure the

of the LO will introduce an additional excess noise to the protocol. Assuming for simplicity we intend to measure the  quadrature (

quadrature ( ). Then the difference in number operator is reduced to

). Then the difference in number operator is reduced to  . Since the fluctuations in intensity and the quadratures are independent random variables, then the variance of the difference in number operator is proportional to the variance of both LO and quadrature operator,

. Since the fluctuations in intensity and the quadratures are independent random variables, then the variance of the difference in number operator is proportional to the variance of both LO and quadrature operator,

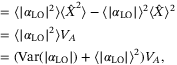

()

() ()

() and

and  is determined by the intensity fluctuations of the LO and VA denotes the variance of the quadrature without considering the effects of the variation of intensity in the LO (ie, Alice's modulation variance). To derive the variance in the measurement of the

is determined by the intensity fluctuations of the LO and VA denotes the variance of the quadrature without considering the effects of the variation of intensity in the LO (ie, Alice's modulation variance). To derive the variance in the measurement of the  quadrature considering all the effects, we rewrite

quadrature considering all the effects, we rewrite  assuming a constant intensity LO with amplitude

assuming a constant intensity LO with amplitude  , and that the RIN in the quadrature measurement is characterized by the variance

, and that the RIN in the quadrature measurement is characterized by the variance  .

.

()

() is the total variance including VA and the variance of the quadrature operator due to the RIN of the LO. Comparing both (29) and (30) we get

is the total variance including VA and the variance of the quadrature operator due to the RIN of the LO. Comparing both (29) and (30) we get

()

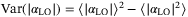

() ()

()We identify two main sources in the fluctuations of the intensity of the LO. One is the fluctuations inherent to the laser when it is generated and the second is the fluctuations caused by the atmospheric fading channel. Since these two random effects are independent, then the noise component due to intensity fluctuations of the LO becomes the sum of the two contributions  . In Reference 24 the noise term12due to the fluctuations of the laser is derived and given for a realistic setup with commonly available lasers. The contribution to the total excess noise is

. In Reference 24 the noise term12due to the fluctuations of the laser is derived and given for a realistic setup with commonly available lasers. The contribution to the total excess noise is  . In Table 2,

. In Table 2,  is shown for a modulation variance of VA = 5.

is shown for a modulation variance of VA = 5.

, we note that the intensity of the LO is measured over the aperture used by the receiver. That is, we consider the total power P over the aperture surface

, we note that the intensity of the LO is measured over the aperture used by the receiver. That is, we consider the total power P over the aperture surface  ,

,

()

() is the normalized intensity variance known as the scintillation index

is the normalized intensity variance known as the scintillation index  . We can quantify the scintillation index averaged over the aperture surface

. We can quantify the scintillation index averaged over the aperture surface  with diameter DR

with diameter DR

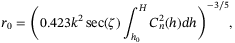

()

() noise component can be rewritten as

noise component can be rewritten as

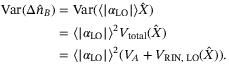

()

() can be obtained for weak atmospheric turbulence by using the atmospheric models presented in the Appendix, and calculating the first- and second-order statistical moments of the irradiance.49 The result is

can be obtained for weak atmospheric turbulence by using the atmospheric models presented in the Appendix, and calculating the first- and second-order statistical moments of the irradiance.49 The result is

()

() is the wavenumber of the laser frequency

is the wavenumber of the laser frequency  (c is the speed of light),

(c is the speed of light),  is the zenith angle, H is the altitude of the satellite at zenith angle

is the zenith angle, H is the altitude of the satellite at zenith angle  , h0 = 0 km is the altitude of the receiver ground station, and

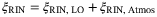

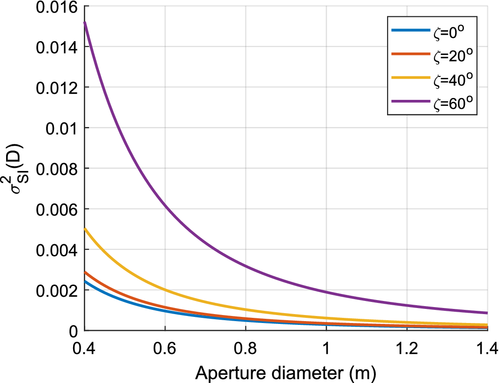

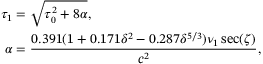

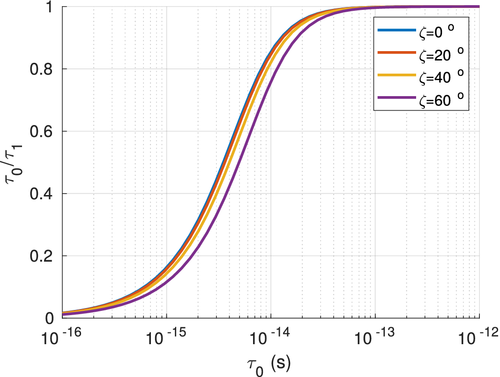

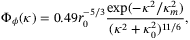

, h0 = 0 km is the altitude of the receiver ground station, and  is the refractive index structure of the atmosphere (see Appendix). In Figure 2, we present the values of

is the refractive index structure of the atmosphere (see Appendix). In Figure 2, we present the values of  for different receiver aperture diameters and zenith angles. We see the importance of using a large aperture in the receiver, since not only is it essential for increasing the transmissivity of the channel but also to reduce the fluctuations on intensity which translates to excess noise. The values of

for different receiver aperture diameters and zenith angles. We see the importance of using a large aperture in the receiver, since not only is it essential for increasing the transmissivity of the channel but also to reduce the fluctuations on intensity which translates to excess noise. The values of  are calculated for the receiver aperture diameter DR = 1 m and DR = 3 m at

are calculated for the receiver aperture diameter DR = 1 m and DR = 3 m at  and altitude H = 500 km are given in Table 2. These are

and altitude H = 500 km are given in Table 2. These are  and 0.004, respectively. For the rest of this article, unless otherwise specified, we use the former value for DR = 1 m.

and 0.004, respectively. For the rest of this article, unless otherwise specified, we use the former value for DR = 1 m.

4.2 Time-of-arrival fluctuations

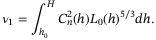

Now we derive the pulse deformations due to transmission through the satellite-to-Earth channel, used in the calculation of the time-of-arrival fluctuations of our Table 2. In Reference 50 an analysis based on the mutual coherence function (MCF) is made, where the two-frequency MCF is defined by the average of all ensemble of pulses (see Equations (11)-(28) in Reference 50). The MCF represents the product of the FSO fields and the turbulence factor based on the first and second-order Rytov approximation. Since LEO satellites are positioned at a high enough altitude we can treat the propagation of the wave as in the far-field regime. In this regime the wave as seen by the receiver corresponds to a plane wave.

where W0 is the beam-waist, L is the total distance travelled by the pulse, and c is the speed of light. The beam-waist is determined by the transmitter aperture diameter which is a fundamental system parameter, as it dominates over many of the effects occurring during optical propagation. The temporal mean intensity in the far-field regime is obtained by averaging over the bandwidth of the MCF at the same radial position and time. From Reference 50, the result is

where W0 is the beam-waist, L is the total distance travelled by the pulse, and c is the speed of light. The beam-waist is determined by the transmitter aperture diameter which is a fundamental system parameter, as it dominates over many of the effects occurring during optical propagation. The temporal mean intensity in the far-field regime is obtained by averaging over the bandwidth of the MCF at the same radial position and time. From Reference 50, the result is

is the initial pulse width, and the broadened pulse width

is the initial pulse width, and the broadened pulse width  is

is

()

() is the following integral (which we evaluate numerically),

is the following integral (which we evaluate numerically),

()

()Here,  where L0 and l0 denote the outer and inner scales, respectively. The inner and outer scales are introduced alongside the atmospheric model described in the Appendix. Any optical pulse sent thought through the atmosphere, will incur deformations due to variations of the refractive index of atmospheric turbulence. To fully analyse the pulse deformations we consider two effects; the broadening of the pulse, and the changes on the time-of-arrival of the pulse. Both of these effects are characterized by the value of

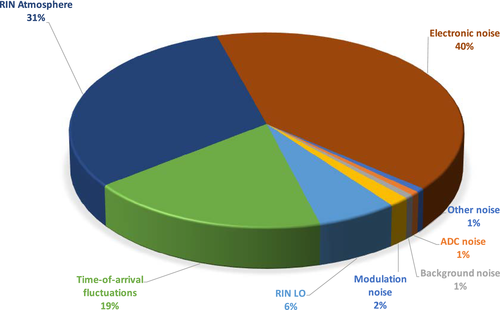

where L0 and l0 denote the outer and inner scales, respectively. The inner and outer scales are introduced alongside the atmospheric model described in the Appendix. Any optical pulse sent thought through the atmosphere, will incur deformations due to variations of the refractive index of atmospheric turbulence. To fully analyse the pulse deformations we consider two effects; the broadening of the pulse, and the changes on the time-of-arrival of the pulse. Both of these effects are characterized by the value of  . First, the broadening of the pulse will cause an attenuation of the average light intensity of the received signal by a factor of

. First, the broadening of the pulse will cause an attenuation of the average light intensity of the received signal by a factor of  .51 In Figure 3, we show the ratio

.51 In Figure 3, we show the ratio  as a function of

as a function of  for the satellite-to-Earth channel with the parameters specified above. We see that the pulse broadening becomes considerable only for pulse widths

for the satellite-to-Earth channel with the parameters specified above. We see that the pulse broadening becomes considerable only for pulse widths  . However, for a pulse width

. However, for a pulse width  ps commonly used in CV-QKD systems consistent with a 100 MHz repetition rate,46 the pulse broadening effect is negligible.

ps commonly used in CV-QKD systems consistent with a 100 MHz repetition rate,46 the pulse broadening effect is negligible.

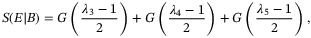

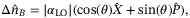

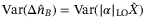

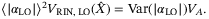

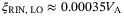

, respectively. In satellite-to-Earth CS-QKD, the fluctuations of the time-of-arrival caused by the atmospheric channel contribute to the total excess noise as an additional amount51

, respectively. In satellite-to-Earth CS-QKD, the fluctuations of the time-of-arrival caused by the atmospheric channel contribute to the total excess noise as an additional amount51

()

() is the timing correlation coefficient between LO and the signal. We set the correlation coefficient between signal and LO to

is the timing correlation coefficient between LO and the signal. We set the correlation coefficient between signal and LO to  as in Reference 51. The noise component due to time-of-arrival fluctuations (39) increases with the pulse width

as in Reference 51. The noise component due to time-of-arrival fluctuations (39) increases with the pulse width  . In Table 2, we determine the value for this noise component to be

. In Table 2, we determine the value for this noise component to be  for a pulse width of

for a pulse width of  ps and central frequency

ps and central frequency  THz (corresponding to a wavelength of 1550 nm).

THz (corresponding to a wavelength of 1550 nm).The LO generated by Alice must have sufficient intensity at Bob such that he can perform a heterodyne/homodyne measurement. Typically, 108 photons per pulse are required at Bob's side. With a 100 MHz pulse repetition rate and pulse width of 130 ps, the required LO average power for a 20 dB channel loss (a typical loss considered here) at Alice's side is 130 mW (at 1550 nm). We have chosen the repetition rate to coincide with current detector technology.46 There are readily available coherent laser sources with these specifications. We assume the ground station has a state-of-the-art homodyne detector as in Reference 47.

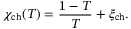

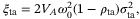

In Figure 4, we compare the noise components contribution for daylight operation. As T gets smaller, the term  in (24) would dominate, but for the purpose of this figure, we compare each noise component on equal footing by setting T = 1 and

in (24) would dominate, but for the purpose of this figure, we compare each noise component on equal footing by setting T = 1 and  . In this figure, we adopt the following values for the noise components. The electronic noise vel = 0.013 is the dominant noise component. The next dominant noise component is the RIN due to the atmosphere. For the purpose of the noise analysis, we assume the realistic scenario, where the satellite zenith angle is

. In this figure, we adopt the following values for the noise components. The electronic noise vel = 0.013 is the dominant noise component. The next dominant noise component is the RIN due to the atmosphere. For the purpose of the noise analysis, we assume the realistic scenario, where the satellite zenith angle is  (which is sufficient for a 2 − 3 minutes flyby2), a transmitter aperture diameter of DT = 0.3 m and a receiver aperture diameter of DR = 1 m with an altitude H = 500 km, implying a RIN of

(which is sufficient for a 2 − 3 minutes flyby2), a transmitter aperture diameter of DT = 0.3 m and a receiver aperture diameter of DR = 1 m with an altitude H = 500 km, implying a RIN of  .

.

for CS-Hom protocol (

for CS-Hom protocol ( ) in the satellite-to-Earth channel for daylight operation. We have used values from Table 2 with laser pulse width

) in the satellite-to-Earth channel for daylight operation. We have used values from Table 2 with laser pulse width  ps and state-of-the-art homodyne detector specifications with NLO = 108. The dominant noise term is the electronic noise at 40%, followed by RIN due to the atmosphere at 31%, the time-of-arrival fluctuations at 19% and the RIN of the LO at 6%. CS, coherent state; LO, local oscillator; RIN, relative intensity noise

ps and state-of-the-art homodyne detector specifications with NLO = 108. The dominant noise term is the electronic noise at 40%, followed by RIN due to the atmosphere at 31%, the time-of-arrival fluctuations at 19% and the RIN of the LO at 6%. CS, coherent state; LO, local oscillator; RIN, relative intensity noiseThe next dominant noise component is the time-of-arrival fluctuations. We set the correlation coefficient between signal and LO to  as in Reference 51. Figure 3 suggests that for pulse widths

as in Reference 51. Figure 3 suggests that for pulse widths  ps, the pulse broadening due to weak turbulence is negligible and

ps, the pulse broadening due to weak turbulence is negligible and  . Thus, the excess noise due to time-of-arrival fluctuations is

. Thus, the excess noise due to time-of-arrival fluctuations is  . As expected, this noise component doesn't depend on the receiver aperture diameter.

. As expected, this noise component doesn't depend on the receiver aperture diameter.

Furthermore,  is 6% of the total excess noise. ADC noise is negligible (1%) as part of the detector noise component. All other noises

is 6% of the total excess noise. ADC noise is negligible (1%) as part of the detector noise component. All other noises  ,

,  , and

, and  are less than 1% of the total excess noise with the exception of the modulation noise which is 2%.24 Therefore, the predicted channel excess noise is

are less than 1% of the total excess noise with the exception of the modulation noise which is 2%.24 Therefore, the predicted channel excess noise is  and the detector excess noise

and the detector excess noise  .

.

5 SECRET KEY RATES OF SATELLITE-TO-EARTH CS-QKD

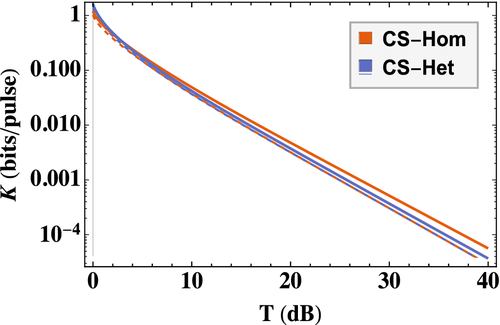

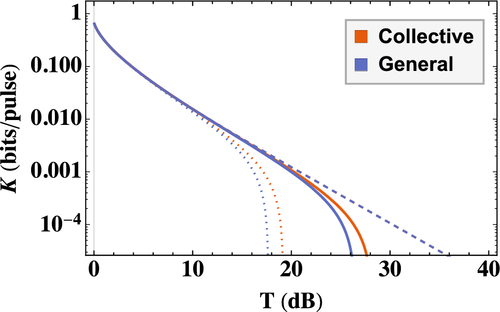

In Figure 5, we calculate the secret key rate in the asymptotic limit against the transmissivity T for both CS-Hom and CS-Het protocols using the parameters in Table 3. Unless otherwise specified, for the rest of the article, we use the parameters in Table 3. The transmissivity on the x-axis is converted to units of dB using the formula  . We compare the channel excess noises of

. We compare the channel excess noises of  and that of our specified satellite-to-Earth channel. For the chosen parameter values, corresponding to a realistic experimental scenario, the difference in the secret key rate between CS-Hom and CS-Het is only evident at low loss in which the CS-Het protocol performs marginally better. The modulation variance VA is an adjustable parameter that can be optimized to maximize the secret key rate with the total excess noise and transmissivity.24 However, in atmospheric channels the transmissivity can fluctuate (although here we assume not) and the optimal value of VA at one time may not be the optimal value at another time. Unless the goal is to maximize the secret key rate each run, additional resources to optimize VA are not necessary. In our system, we choose a value of VA = 5 which is in the range of optimality for the values of transmissivity in the satellite-to-Earth channel.

and that of our specified satellite-to-Earth channel. For the chosen parameter values, corresponding to a realistic experimental scenario, the difference in the secret key rate between CS-Hom and CS-Het is only evident at low loss in which the CS-Het protocol performs marginally better. The modulation variance VA is an adjustable parameter that can be optimized to maximize the secret key rate with the total excess noise and transmissivity.24 However, in atmospheric channels the transmissivity can fluctuate (although here we assume not) and the optimal value of VA at one time may not be the optimal value at another time. Unless the goal is to maximize the secret key rate each run, additional resources to optimize VA are not necessary. In our system, we choose a value of VA = 5 which is in the range of optimality for the values of transmissivity in the satellite-to-Earth channel.

(solid) and our chosen satellite-to-Earth channel (dashed). CS, coherent state

(solid) and our chosen satellite-to-Earth channel (dashed). CS, coherent state| DR | H |  |

|

|

VA |  |

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 m | 500 km | 60o | 0.95 | 0.95 | 5 | 130 ps | 1550 nm | 0.0186 | 0.0133 |

In Figure 6, we calculate the secret key rate in the finite case against the transmissivity T. As seen in Figure 6 for the CS-Het protocol, the loss that can be tolerated (compared with the asymptotic limit) is less in the finite-size regime for n = 1010 and n = 1012. In this same figure, we compare the key rates for collective and general attacks using the failure probability  and

and  (

( ), respectively. It is evident that the general attack does not tolerate as much loss. Note it is straightforward to convert all key rate into units of bits/s by multiplying by the laser pulse repetition frequency.13

), respectively. It is evident that the general attack does not tolerate as much loss. Note it is straightforward to convert all key rate into units of bits/s by multiplying by the laser pulse repetition frequency.13

In Table 4, the individual impact of each noise term on the secret key rate under collective Gaussian attacks is shown14 in the finite-size regime with n = 1012. The background noise during daylight is approximately 1% of the total excess noise for 1550 nm light (0.0002).43 In DV-QKD, background noise from daylight can be mitigated using small spatial filtering coupled with advanced adaptive optics.54 It was noted in Reference 3 that optical systems used in CV-QKD could also use small spectral bandwidth. Consequently, the background noise can be filtered, allowing for daylight operation. Daylight CV technology was demonstrated in Reference 55, but there are no corresponding studies for CV-QKD.

for no impact and

for no impact and  for maximum impact)

for maximum impact)| Parameter | Description | Value |  @ 10 dB @ 10 dB |

@ 20 dB @ 20 dB |

@ 30 dB @ 30 dB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Channel excess noise | 0.0186 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.00 |

|

Time-of-arrival fluctuations | 0.006 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.00 |

|

Relative intensity noise due to atmosphere | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.00 |

|

Background noise | 0.0002 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.93 |

|

Detector efficiency | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| vel | Electronic noise | 0.013 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.81 |

-

Note: Other parameter values: n = 1012,

, modulation variance VA = 5 and reconciliation efficiency

, modulation variance VA = 5 and reconciliation efficiency  .

. - Abbreviation: RIN, relative intensity noise.

We find that the background noise component during daylight in CS-QKD in the satellite-to-Earth channel has a negligible impact on the secret key rate, in agreement with Reference 43. For night-time operation, the secret key rate would be unchanged with  . Thus, the secret key rate in Figure 6 is a lower bound, and night-time operation would improve the key rates, but is not essential.

. Thus, the secret key rate in Figure 6 is a lower bound, and night-time operation would improve the key rates, but is not essential.

We consider how increasing the size of the receiver aperture improves the secret key rates under general attacks. For a larger receiver aperture of DR = 3 m, we obtain a smaller channel excess noise of  and detector excess noise of

and detector excess noise of  . At the transmissivity T = 15 dB, a secret key rate of 2.6 × 10−3 bits/pulse is attained under general attacks for this larger receiver aperture. T = 15 dB is readily achievable in the satellite-to-Earth channel using this larger receiver aperture. For example, for the transmitter aperture of DT = 0.3 m at transceiver separation 1200 km the beam width at the ground is 12 m (and a diffraction-limited divergence of 10

. At the transmissivity T = 15 dB, a secret key rate of 2.6 × 10−3 bits/pulse is attained under general attacks for this larger receiver aperture. T = 15 dB is readily achievable in the satellite-to-Earth channel using this larger receiver aperture. For example, for the transmitter aperture of DT = 0.3 m at transceiver separation 1200 km the beam width at the ground is 12 m (and a diffraction-limited divergence of 10  rad), giving a diffraction loss of 22 dB for receiver aperture DR = 1 m (see discussion below for Micius). Extrapolating from these parameters, the receiver aperture diameter of DR = 2.3 m gives a diffraction loss of 15 dB. For this receiver aperture of DR = 2.3 m, the channel excess noise is

rad), giving a diffraction loss of 22 dB for receiver aperture DR = 1 m (see discussion below for Micius). Extrapolating from these parameters, the receiver aperture diameter of DR = 2.3 m gives a diffraction loss of 15 dB. For this receiver aperture of DR = 2.3 m, the channel excess noise is  and a secret key rate of 2.4 × 10−3 bits/pulse is attained under general attacks.

and a secret key rate of 2.4 × 10−3 bits/pulse is attained under general attacks.

We consider how the secret key rate changes with the system parameters in Table 3. For example, doubling the pulse period to  ps, will give a channel excess noise of

ps, will give a channel excess noise of  . However, the secret key rate is barely changed (ie, 1.0 × 10−3 bits/pulse). We also find that from VA = 2 to VA = 8, the result doesn't significantly change. Hence, this main result is not sensitive to the parameters we have chosen for the figures.

. However, the secret key rate is barely changed (ie, 1.0 × 10−3 bits/pulse). We also find that from VA = 2 to VA = 8, the result doesn't significantly change. Hence, this main result is not sensitive to the parameters we have chosen for the figures.

As we grew close to the completion of our study, two other works appeared; one39 that can be made applicable to satellite-to-Earth channels and one56 directly applicable to these channels. Different from our study, these latter works had a focus on the large-scale fading effects on the QKD key rates, and different excess noise contributions. They, therefore, apply to different system models than the diffraction-only loss models we explored here. However, collectively the works of References 39, 56 and ours illustrate clearly that CV-QKD in the satellite-to-Earth channel is feasible.

Although our focus has been to demonstrate the viability of the CS-QKD protocols in satellite-to-Earth channel, it is perhaps interesting to compare our results directly with Micius. In our calculations of the secret key rates, we have assumed that transmissivity is constant.15That is, transmissivity fluctuations due to atmospheric turbulence and beam-wandering are assumed small in comparison to diffraction losses.57 As just mentioned above, in the Micius satellite QKD experiment, the satellite-to-Earth channel loss due to diffraction was 22 dB at a maximum distance of 1200 km with a transmitter aperture of DT = 0.3 m, a far-field divergence of 10  and receiver aperture of DR = 1 m.2 Additional loss occurred via atmospheric absorption and turbulence (3 to 8 dB), and loss due to pointing error (<3 dB). This gave an average total loss of 30 ± 3 dB. In calculations of the Micius QKD key rate, the failure probability was set to

and receiver aperture of DR = 1 m.2 Additional loss occurred via atmospheric absorption and turbulence (3 to 8 dB), and loss due to pointing error (<3 dB). This gave an average total loss of 30 ± 3 dB. In calculations of the Micius QKD key rate, the failure probability was set to  which gave a key rate of 1.38 × 10−5 bits/pulse. In comparison, for our CS-Het protocol at the same security setting and same losses we find zero key rate under general attacks. It is only for losses less than 25 dB that we find nonzero rates under general attacks. We do caution, however, that direct comparisons of these two very different technologies (DV vs CV) are limited in value because the security assumptions are different. We also point out the Micius security analysis disregards information leakage due to side-channel imperfections.2 Other assumptions underpinning the Micius key rate are discussed in Reference 58. However, to be fair, we have also overlooked some assumptions that underpin our CV-QKD analysis. The most important of these are in regard to the LO—an issue we discuss next.

which gave a key rate of 1.38 × 10−5 bits/pulse. In comparison, for our CS-Het protocol at the same security setting and same losses we find zero key rate under general attacks. It is only for losses less than 25 dB that we find nonzero rates under general attacks. We do caution, however, that direct comparisons of these two very different technologies (DV vs CV) are limited in value because the security assumptions are different. We also point out the Micius security analysis disregards information leakage due to side-channel imperfections.2 Other assumptions underpinning the Micius key rate are discussed in Reference 58. However, to be fair, we have also overlooked some assumptions that underpin our CV-QKD analysis. The most important of these are in regard to the LO—an issue we discuss next.

6 LO HACKING

6.1 Attacks

An underlying assumption implicit in key rates we have determined for the CS-QKD protocols is that the transmission of the LO through the satellite-to-Earth channel is secure and not interfered with. However, clearly this assumption is suspect as an eavesdropper can in principle obtain access to the LO, modify the channel, and subsequently obtain information on the quantum key. Here, we briefly discuss this important caveat. We mention some specific attacks and some countermeasures.

6.1.1 Equal-amplitude attack

In this attack, Eve intercepts both the LO and quantum signal and performs homodyne detections on both.59 Eve produces two squeezed states with the same intensity level. Bob cannot discover the attack because the expected noise is less than the shot noise level. When Bob compares the difference in his measurement with Alice's prepared state to the threshold from theoretical security proofs, he mistakenly confirms the channel is secure.32, 60 Eve has therefore compromised the channel. However, this security loophole can be solved if Bob can monitor the fluctuations in the intensity of the LO.61

6.1.2 Wavelength attack

In this attack, Eve modifies the intensity transmission of Bob's beamsplitter by changing the wavelength of the light from Alice. This wavelength attack deems the final keys insecure. However, it was shown in Reference 62, that adding a simple wavelength filter randomly before measuring the intensity of the LO can prevent this attack.

6.1.3 Calibration attack

The device calibration routine of the LO is susceptible to an intercept-resend attack. In this attack, Eve manipulates the LO pulses to change the clock pulses used for detection.63 More specifically, Eve changes the shape of the LO pulse which consequently induces a delay in the clock trigger. The homodyne detection will measure a lower intensity. Therefore, there will be a decrease in the response slope between the variance of the homodyne detection and the LO power. As a result, the shot noise will be overestimated and the excess noise underestimated.64 Countermeasures to this attack involves monitoring the shot noise in real time.

6.2 Local local oscillators

Motivated by these security loopholes, there has recently been a focus on using true local oscillators or local local oscillators (LLO). In such systems, two lasers are used, one at Alice for generating the quantum signal and another at Bob for the LLO. Reference pulses are sent with the signals which are used to calibrate the phase offset in the LLO.44, 65-67 However, the phase offset derived from the reference pulses is limited by quantum uncertainty, and the two lasers necessarily introduce some phase drift. In comparison to optical fiber, no phase compensation method exists for the LLO in FSO channels where additional phase noise due to atmospheric turbulence is expected,68 but these are not insurmountable issues. Despite their intuitive appeal over LO schemes, attack strategies against LLO schemes do exist. In one such attack recently proposed,69 Eve intercepts the reference pulse and estimates the phase drift using Bayesian algorithms. Consequently, the excess noise is biased to mask an intercept-resend attack and a beam-splitter attack.

In general, any pilot symbol scheme (eg, reference pulses) is always subject to manipulation by an adversary, and therefore susceptible to attacks outside the scope of current security proofs.31 Formal security analyses that account for the optimal general attack on both quantum signals and pilot symbols are needed to close this security gap. An alternative approach would be the use of a system that avoids the use of any reference signals at all for the phase referencing. Only by this means do the assumptions underpinning formal security proofs for the CV-QKD protocols we have discussed here remain intact. Recent work along these lines is given in Reference 70 where publicly announced raw key values are invoked to determine the phase offsets to be applied to the LLO. However, currently even this type of phase determinations for the LLO are not formally proven secure—an issue that hopefully will be addressed in forthcoming works.

7 DISCUSSION

In our work, we have deliberately focused on the feasibility of the simplest-to-deploy CS-QKD protocols over the satellite-to-Earth channel for which composable security is known. The reason for choosing the simplest-to-deploy CS-QKD protocols was twofold. First, early CV-based satellites will certainly deploy one of these protocols, if not both. Second, if the easiest-to-deploy protocols were shown to lead to close-to-zero key rates then more sophisticated protocols (with likely lower key rates) would likely be not interesting.

Our work largely focused on the on CS-Het protocol for which composable security in the finite key limit (ie, a deployable scenario) is known. However, it is worth mentioning that other CV-QKD protocols exist for which composable security in the finite limit is also known, such as two-mode squeezed state CV-QKD protocol.71 These other protocols in the finite-key setting are generally either more difficult to deploy or have lower expected key rates, relative to CS-Het.

An approach to preventing side-channel attacks against detectors is available via CV measurement device-independent (CV MDI-QKD) protocols. These types of CV-QKD protocols allow for untrusted devices that act as relays. Interestingly, formal proofs of security in the finite regime are known for CV MDI-QKD.38, 72, 73 An improvement to this protocol, the coherent-state-based “Twin-Field” (TF)-QKD protocol (an extension of Reference 74), has been recently proposed, for example, References 75, 76 and proof-of-principle experiments carried out in optical fiber.77 Information-theoretic security in the finite regime for CS TF-QKD has also been proposed.78 However, we do note that in scenarios where the untrusted relay is a satellite being served in the uplink, both MDI-QKD and TF-QKD will suffer losses substantially larger than the downlink losses. Phase referencing between the uplink signals sent from Alice and Bob (and authentication of each pulse so referenced—at the cost of key consumption), and phase compensation of the signals traversing the different FSO uplink channels, must also be included. All these issues will reduce the final key rate.

8 CONCLUSION

In this work, we investigated the feasibility of the simplest-to-deploy CV-QKD protocols, the CS-QKD protocols, over the satellite-to-Earth channel. We reviewed the security of these two protocols, as well as the components of the total excess noise most relevant to the satellite-to-Earth channel. Through new calculations we then determined that the most important sources of noise in our protocols over the satellite-to-Earth channel was the RIN due to the atmosphere, and the time-of-arrival fluctuations between the signal and LO. We next focused on the CS-QKD protocol with heterodyne detection in the deployable setting of a finite key regime. Given reasonable transceiver aperture sizes, and assuming diffraction as the only source of loss, we found that reasonable QKD key rates under general attacks can be anticipated. We, therefore, concluded that CV-QKD with information-theoretic security in the satellite-to-Earth channel is entirely feasible. In closing, we noted our information-theoretic security assumes that the LO is secured from manipulation by an adversary. Future useful work in this area could include formal security proofs of finite-limit CS-QKD with homodyne detection, and formal proofs of security under LO (or reference pulse) attacks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was a collaboration between the Commonwealth of Australia (represented by the Defence Science and Technology Group) and the University of New South Wales through a Defence Science Partnerships agreement.

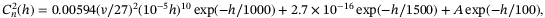

Appendix A: Atmospheric models

Turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere is caused by random variation in temperature and pressure. These variations alter the air's refractive index both spatially and temporally, distorting any optical waves propagating through the atmosphere. Distortions of the pulses transmitted such as beam deformation and beam wandering are one of the main sources of photon loss in the channel. To model the effects of the turbulent atmosphere on the optical signals we use Kolmogorov's theory of turbulent flow.79 The strength of the turbulence is characterized by the refractive index structure parameter,  . Kolmogorov's theory is based upon the insight that turbulence is induced by eddies in the atmosphere. The scale of the turbulence can be characterized by an inner-scale l0, and an outer-scale L0.49 Eddies with a size lower than the inner-scale cannot exist since the turbulence at such scales is dissipated into the atmosphere as heat. The outer-scale denotes the upper-bound to the eddy size and is the scale at which energy is injected into the turbulence.

. Kolmogorov's theory is based upon the insight that turbulence is induced by eddies in the atmosphere. The scale of the turbulence can be characterized by an inner-scale l0, and an outer-scale L0.49 Eddies with a size lower than the inner-scale cannot exist since the turbulence at such scales is dissipated into the atmosphere as heat. The outer-scale denotes the upper-bound to the eddy size and is the scale at which energy is injected into the turbulence.

()

() at the ground. In addition, measurements made of the scintillation suggest the outer scale L0 changes with the altitude according to the empirical Coulman-Vernin profile81

at the ground. In addition, measurements made of the scintillation suggest the outer scale L0 changes with the altitude according to the empirical Coulman-Vernin profile81

()

()Finally, the inner scale is assumed to directly proportional to the outer scale  , with

, with  .50

.50

()

() the radial spatial frequency on a plane orthogonal to the propagation direction,

the radial spatial frequency on a plane orthogonal to the propagation direction,  ,

,  , and r0 the Fried parameter for a vertical propagation length49

, and r0 the Fried parameter for a vertical propagation length49

()

()

REFERENCES

- 1 Currently, a formal proof of security in the finite limit for the CS-Hom protocol is unavailable.

- 2

We implicitly assume in all calculations that the vacuum noise is normalized to 1 by setting

.

. - 3 When we refer to “secret key rate” in this article, we actually mean a lower bound on the rate.

- 4 d is the bits of precision encoded by the symbol. In this work, we set d = 5 as in Reference 38.

- 5

In a real-world deployment the maximum-likelihood estimators can be computed from the measurement data to determine Tmin and

.35, 36

.35, 36 - 6 In the rest of the article, unless stated otherwise, we choose ne = n = 1012, implying n/N = 0.5.

- 7 Even in cases where nonconstant transmissivity is present, channel postselection using the LO can render a subset of the channels to lie within an effective constant transmissivity window. QKD rates can then be approximated via summation of rates arising from these subsets.

- 8 Note the QKD key rates of Reference 41 are based on the use of an LO generated directly at the receiver (not one transmitted with the signal), and therefore cannot be directly compared with the key rates reported here.

- 9

In the limit of T → 0, Bob's variance of the quadrature operator reduces to

as expected.

as expected. - 10

The channel excess noise is defined with respect to the input, and is thus multiplied by the transmissivity T and

in the covariance matrix.

in the covariance matrix. - 11

The detector excess noise is defined with respect to the output and hence T and

cancel out in the covariance matrix.

cancel out in the covariance matrix. - 12

where RINLO = 1.4 × 10−7Hz−1 is the RIN and BLO = 10 KHz is the optical bandwidth of the LO.24

where RINLO = 1.4 × 10−7Hz−1 is the RIN and BLO = 10 KHz is the optical bandwidth of the LO.24 - 13 In real-world cryptography it is the key rate in bits/s that is ultimately of interest. However, conversion from bits/pulse to bit/s must consider the time to decode the finite, but very large, block lengths (multiplying by the pulse repetition rate is only formally valid when the reconciliation time is zero). Optimization of the bit/s key rate can be nontrivial in some circumstances.53

- 14 Note in our calculations we have assumed that the transmissivity remains constant over the block length. Receiving a block length of 1012 from a 100 MHz source would require minutes of transmission time. For block lengths larger than 1010 it is likely that the impact of satellite motion on transmissivity would need to be considered within the calculations unless a corresponding higher-rate source was utilized.

- 15

The statistical nature of the turbulence only manifests itself in our calculations through the excess noise contributions. In particular, this is through the impact of scintillation on

and on the random refractive index perturbations on

and on the random refractive index perturbations on  . Under the assumption of diffraction-only losses, the constant transmissivity T of the channel is determined via the system parameters, DT, DR, and L. Of course, these parameters must be set so that the diffraction-only loss assumption is a reasonable one.

. Under the assumption of diffraction-only losses, the constant transmissivity T of the channel is determined via the system parameters, DT, DR, and L. Of course, these parameters must be set so that the diffraction-only loss assumption is a reasonable one.