A systematic review on the use of the emotion thermometer in individuals diagnosed with cancer

Abstract

Objective

Physiological and psychological sequelae are frequent after a cancer diagnosis and also on the long term. Screening could help detect psychological distress early and thus enable timely provision of adequate treatment. The emotion thermometer (ET) is a validated screening tool including five dimensions (distress, anxiety, depression, anger, and need-for-help). Reviewing the literature, we aimed to describe (a) the validity and (b) the application of the ET.

Methods

Six databases were systematically searched for studies using the ET in individuals diagnosed with cancer. Included studies were critically appraised for methodological quality. ET validity and application were narratively synthesized.

Results

We identified 580 records eligible for title-abstract screening. Seventeen studies based on 13 different populations were included. Validation studies (5 of 17) concluded that the ET is sensitive to distress detection, delivering prompt and accurate results with no negative impact on clinic visit time. Furthermore, its use is accepted in patients and clinicians. The remaining 12 exploratory studies applied the ET for screening purposes (3 of 12), as outcome measure (6 of 12), or as predictor variable measure (3 of 12). Most studies were conducted in Europe (11 of 17), and 7 of the 12 exploratory studies used the recommended cutoff (greater than or equal to 4). Study populations were mostly female (9 of 13) with a mean age greater than 50 years (12 of 13) at study.

Conclusions

Publications on distress screening with the ET are scarce, especially among young populations. However, research and studies' recommendations support the ET's utility as a valid and feasible tool for distress screening including anxiety and depression and suggest its implementation as part of a structured program for early screening in cancer care.

1 BACKGROUND

Besides many physiological side effects, a cancer diagnosis also exerts a profound psychological impact on the patient.1-4 According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), emotional concerns cancer patients experience, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and spiritual crisis,5 are best represented by using the term “distress” since it does not carry the stigma of other words used for emotional symptoms such as “feeling depressed” or “being emotional.”5

Distress in cancer patients and survivors may interfere with the ability to cope with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment. Patients and survivors are at higher risk for distress when compared with the norm population, even long after therapy has ended.4, 6-8 Approximately one in four survivors reported moderate to severe psychological distress, which here is referred to as distress.8-11

Heightened distress has been associated with worse quality of life,12 unmet needs in care, poorer adherence to treatment recommendations,13 and poorer survival.2 This consistent evidence has promoted the development of distress screening guidelines for cancer patients and survivors during and after treatment.5, 14-16 Screening tools are used to detect early signs of a problem to improve the chances of effective interventions and reduce symptom burden. However, screening instruments should not substitute careful clinical assessment but rather be complementary facilitators for symptom detection.

Research on psychological and emotional distress in cancer patients and survivors continuously demonstrates not only the high prevalence of psychological and emotional distress but also the need for short, accurate, and valid screening tools.14, 17-20

One of the predominant instruments that is highly encouraged in its use and adopted into recommendations by the NCCN is the distress thermometer (DT).5 The DT is a single-question visual-analog scale in the shape of an analog thermometer (range: 0-10; cutoff ≥ 4), a so called ultrashort screening tool. It has increasingly been accompanied by the Problem List (PL), including 39 items.5, 20, 21 The DT has been thoroughly investigated and compared with other screening instruments.19, 22, 23 Building on the DT's strengths, a new and promising tool, the emotion thermometer (ET), was designed.24, 25 The original ET combines five domains—four emotion domain thermometers as a core set (distress, DT; anxiety, AnxT; depression, DepT; and anger, AngT) and one outcome domain thermometer (need for help, HelpT)—in visual-analog format.24, 25 It was developed stepwise in 2007 by a research group around Alex J. Mitchell. It has since been validated as a screening tool sensitive to the detection of cancer distress and reasonable in its length for use in acute and time-constrained clinical settings.24, 26, 27 Later versions of the ET include outcome domains such as duration of illness, burden and quality of life, a Concerns Checklist, and a palliative version including pain assessment. In 2012, the DepT was launched as a standalone tool.28 The ET is therefore of modular character, where one can add any thermometer to the core set consisting of the four emotion domain thermometers. The ET has been professionally translated into 15 languages. So far, no overview on the validity and applicability of the ET in the oncological setting is available.

This systematic review has the overall objective of reviewing publications on the use of the ET in the oncological setting. Specifically, we aimed to describe (a) the validity and (b) the application of the ET.

2 METHODS

We conducted a systematic literature review to report on validity and application of the ET in individuals diagnosed with cancer. A review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID:CRD42018084063;https://www.crd.york.ac.uk).

2.1 Search strategy

We searched CINAHL, COCHRANE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, PubMed, and SCOPUS for relevant literature until 10 September 2018 using the following search terms:

(cancer OR neoplasm* OR malignancy* OR oncolog* OR carcinoma* OR tumor OR tumors OR tumour* OR blastoma* OR sarcoma* OR leukaemia* OR leukemia* OR lymphoma* OR medulloblastoma* OR metastasis OR radiotherapy OR chemotherapy) AND (emotion AND thermometer) OR emotion thermometer.

Additionally, reference lists of identified reviews and included publications were hand-searched for additional literature. Duplicates were discarded. The search was neither date nor language limited.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Publications were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: original research article from peer-reviewed journal, sample size greater than 20, study including individuals diagnosed with cancer, and use of the ET (minimum requirement: core set: DT, AnxT, DepT, and AngT). Editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, reviews, and study protocols were excluded.

2.3 Data extraction

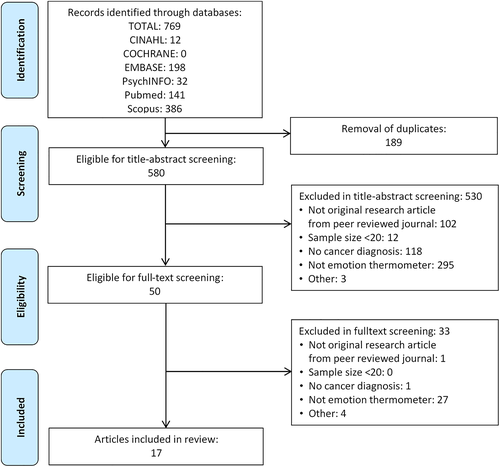

Checking studies for eligibility with the defined inclusion criteria was carried out independently by two reviewers each (EH, KR, and GM) in two phases: first, title-abstract screening, then full-text screening. Discordances were resolved through discussion. Selection process of eligible studies is shown in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram). A data extraction form was created for consistent data extraction.

2.4 Quality assessment

To assess study quality, we developed 11 questions covering six categories based on the Appraisal Tool for Cross Sectional Studies (AXIS)29 and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP)30 for quantitative studies. Finally, the ratings of the six categories were combined into two global quality ratings for each study, an “ET rating” and a “general rating” (Tables S1 and S2). The quality of each study was independently assessed by two reviewers (EH and KR). Discordances were resolved through discussion.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search results

The systematic search identified 769 publications until 10 September 2018. After removing189 duplicates, 580 publications were screened on the basis of title and abstract. Subsequently, 50 full texts were screened for inclusion. Finally, 17 studies were included in the review (Figure 1).

3.2 Overview of published research

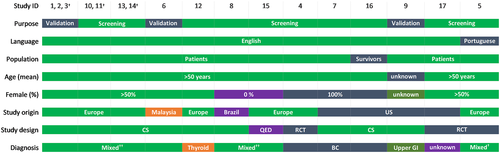

The 17 included publications were based on 13 study populations (Tables 1 and S3, Figure 2).

| ID, First Author (year) | Purpose: Validation, Screening, Outcome Measure, Predictor Variable Measure | Cutoff | Distress Prevalence: Mean (SD) and/or Percentage | Use: Combinationa, Comparisonb, or Single Instrumentc | Other Instruments | Validation | Reasons to Use the ET | Conclusion with Respect to the ET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, Mitchell, (2010)24 | Validation | ≥4 |

DT: 2.89 (2.96) AnxT: 4.78 (3.00) DepT: 2.34 (2.63) AngT: 2.02 (2.89) 88.5% scored ≥4 on at least one domain |

Comparison | HADS total score, anxiety subscale, depression subscale; DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depression, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) |

HADS and DSM-IV symptom criteria

Distress (HADS total: ≥15): AngT best predictive summary index (PSI); DepT cutoff ≥2; AnxT and AngT cutoff ≥3

Anxiety (HADS anx.: ≥8): AnxT best PSI; DT cutoff ≥2, AnxT cutoff ≥6; DepT cutoff ≥2; AngT cutoff ≥3

Depression (HADS dep.: ≥8): DepT best PSI cut-off ≥4; same for DT; AnxT cut-off ≥8; AngT cut-off ≥5

Major Depression by DSM-IV: DepT best PSI, cut-off ≥4 |

None |

The expansion of the DT to the ET identifies those that score below DT cutoff but still record emotional difficulties on at least one of the ET domains (51% of participants). Some emotional concerns are not captured by the concept of distress as measured by the DT alone. To detect broadly defined distress, AngT seemed promising, maybe better than DT alone. To detect anxiety, AnxT was somewhat more accurate than DT. To detect depression, DepT was found to be the optimal method. ET seems to be more accurate than the DT alone. ET is equally acceptable to patients and typically takes less than 1 min to complete. |

| 2, Mitchell, (2010)25 | Validation | Many | n.a. | Comparison | HADS, DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depression, and PHQ-9 |

Depression (PHQ-9, cut off ≥10, HADS dep. cutoff ≥8) Optimal: DepT cutoff ≥6.5

Depression (DSM-IV): Optimal: DepT cutoff ≥7

Distress (HADS total: ≥15): Optimal: 3 thermometers, DepT ≥2.5, AngT ≥3.5, & HelpT ≥2.5

Anxiety (HADS anxiety score cutoff ≥8): Optimal: 2 thermometers: DepT & AnxT |

None |

For the assessment of distress and anxiety, a combination of thermometers was superior to any single thermometer. In situations where “any significant emotional difficulty” is looked for, it is unlikely that one thermometer would be sufficient, and, therefore, the ET is recommended. For depression, one single thermometer, the DepT, was optimal on its own, thus a single thermometer to screen for depression might suffice. |

| 3, Baker-Glenn, (2010)31 | Validation | ≥4 |

Of the distressed patients (DT), 36.7% wanted help (single help question). Of the not distressed (DT) patients, 90.1% perceived a desire for help. Of those wanting help (single help question), 34.6% scored ≥4 on all four ET domains. Of those not wanting help (single help question), 10.6% scored ≥4 on four ET domains. All of the differences between the five ETs for those wanting help and those not wanting help (single help question) were significant at P < .05 (Pearson chi2 test): • DT: 69% vs 30% • DepT: 62% vs 22% • AnxT: 92% vs 58% • AngT: 46% vs 21% • HelpT: 62% vs 11% Variables most associated with desire for help were distress (DT SMW = 0.27), anxiety (HADS-A SMW = 0.23), and depression (HADS-D SMW = 0.12) |

Comparison | HADS, DSM-IV symptom criteria for major depression, and PHQ-9. |

Perceived desire for help ET help: • Of those wanting help (single help question): mean = 4.4 • Of those not wanting help (single help question): mean = 1.3

Use of the ET help as a predictor of desire for help (single help question) ROC curve analysis: cutoff ≥3 maximizes se = 1.00, sp = 0.66, positive predictive value (PPV) = 0.43, negative predictive value (NPV) = 1.00; 80% of people were correctly classified (single help question). |

None | Findings suggested that relying on the help question (alone or in combination with the PHQ-2) was not effective as a distress screening tool. However, the HelpT correctly identified 80% of the participants with need for help (cutoff ≥ 3). Patients with higher levels of distress expressed most desire for help, but simultaneously, more than half of them were either unable to express this need or did not regard their symptoms as important enough to ask for help. On the other hand, patients who did not score highly on measures of psychological symptoms nevertheless wished to receive further assistance. Ultimately, asking patients about desire for help gives valuable information not achieved by mood screening only. |

| 4, Romito, (2013)32 | Outcome measure | n.a. |

IG: DT: 5.6 → 3.3, AnxT: 5.9 → 3.3 DepT: 4.1 → 2.3 AngT: 4.7 → 2.4 HelpT: 6.5 → 8.3

CG DT: 4.5 → 3.8 AnxT: 4.5 → 3.5 DepT: 2.7 → 2.5 AngT: 3.6 → 3.3 HelpT: 5.8 → 3.3 |

Single instrument | None | None | None | None |

| 5, Deep, (2013)33 | Outcome measure | ≥4 |

IG baseline DT: 7.97 AnxT: 7.8 DepT: 7.71 AngT: 5.57 HelpT: 7.11

CG baseline DT: 7.29 AnxT: 7.46 DepT: 7.17 AngT: 5.71 HelpT: 6.14 |

Combination |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21, Satisfaction with Social Support Scale, and two additional domains to the ET (duration of illness and burden). |

None | None | None |

| 6, Beck, (2014)26 | Validation | Many |

DT: 1.93 (2.46) AnxT: 2.16 (2.47) DepT: 1.63 (2.27) AngT: n.a. Correlation ET and HADS: DepT and HADS depression subscale (r = 0.645, sign.); AnxT and HADS anxiety subscale (r = 0.632, sign.); DT and HADS total (r = 0.649, sign.) |

Comparison | HADS to correlate the predictability of the ET; MINI as gold standard. |

DepT/MINI dep.: AUC = 0.76 for cutoff = 3; best balance for se = 0.698 and sp = 0.824;

DT/MINI dep.: AUC = 0.72 for cutoff = 2 (se = 0.792, sp = 0.645);

DT/MINI anx.: AUC = 0.77 for cutoff = 4 (se = 0.700,sp = 0.829)

AnxT/MINI anx.: AUC = 0.76 for cutoff = 4 (se = 0.733; sp = 0.780) |

None | ET has good criterion validity. The variety of ET domains allows patients to fully understand the emotional symptoms investigators are trying to assess for. |

| 10, Kallay, (2014)34 | Outcome measure | ≥4 |

Male: DT: 56.23% AnxT: 67.99%; AngT: 26.53%; DepT: 27.14%; HelpT: 47.57%

Female: DT: 68.67%; AnxT: 49.43%; AngT: 33.88%; DepT: 35.42%; HelpT: 51.04% |

Combination | BDI for depression, FACT-G for well-being. | None | Screening for distress, the identification of patients at risk, and the efficient management of mental health problems of patients and families are of extreme salience. | Timely and accurate assessment of distress. |

| 7, Schubart, (2014)35 | Screening | ≥4 |

DT: 22% AnxT: 28% AngT: 14% DepT: 18% BurdenT: 16% HelpT: 10% Of the patients in this study, 35% scored above the previously validated cut point of ≥4 on at least one of the emotion domain thermometers. |

Single instrument | CC | None | Study confirms the need to screen for psychological distress in breast cancer patients. |

The study demonstrates the feasibility of distress screening using the newly modified ET and an additional CC, specific to breast cancer patients' needs. Its implementation did not impact clinic visit times. The CC is an important component for more comprehensive screening specific to breast cancer patients. |

| 8, De Cerqueira, (2015)36 | Outcome measure | n.a. | FC group: AnxT mean = 4. All other results stayed <4. No difference between the three groups in their ET. | Combination | International Index of Erectile function, International Prostate Symptom Score, BAI, Beck Hopelessness Scale, BDI, and SF-36. | None | None | None |

| 9, Schubart, (2015)27 | Validation | ≥4 |

DT: 14% AnxT: 17% AngT: 6% DepT: 12.5% Optimal strategy for nondepressed status: cutoff <5; mild depression or higher: extended ET (7 items), BurdenT cutoff <5, optimal (using original ET) depression status: DepT cutoff >3 and DT cutoff >5 |

Comparison | BDI-II, CC |

BDI-II Diagnostic accuracy for each ET (≥4) against BDI-II: DT (se = 0.5, sp = 0.942) AnxT (se = 0.583, sp = 0.923) DepT (se = 0.583, sp = 0.885) AngT (se = 0.333, sp = 0.981) |

Study indicates that the ET instrument, which takes between 1 and 1.5 min to complete, measures depression with a reasonable degree of accuracy compared with the BDI-II, which can take 5–10 min to complete. | ET is an acceptable screening tool to identify unmet needs for psychosocial help in a sample of upper GI cancer patients. |

| 13, Pina, (2015)37 | Predictor variable measure | ≥4 |

DT: 56% AnxT: 73% AngT: 58.2% DepT: 75.5% HelpT: 56.3% |

Combination | ECOGS, BDI, CAGE alcohol questionnaire, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, HADS. | None | None | None |

| 11, Faludi, (2016)38 | Predictor variable measure | ≥4 |

DT:58.5% (low: n = 277; high: n = 390); AnxT:42.6% (low: n = 437; high: n = 325); DepT:32.5% (low: n = 514; high: n = 247); AngT:30.8% (low: n = 528; high: n = 235); HelpT:50.2% (low: n = 380; high: n = 383) |

Single instrument | None | None | None | None |

| 15, Lange, (2017)39 | Outcome measure | n.a. |

IG: DT: 2.75 → 2.93 AnxT: 2.69 → 1.72 DepT: 1.78 → 1.70 AngT: 1.69 → 1.8 HelpT: 1.86 → 1.01

CG: DT: 2 → 2.09 AnxT: 1.88 → 1.39 DepT: 1.22 → 0.94 AngT: 0.88 → 0.64 HelpT: 1.08 → 0.84 |

Combination | SF-8, Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer-PC, Cancer Coping Questionnaire. | None | None | None |

| 12, Rogers, (2017)40 | Screening | ≥4 |

DT: 13% AnxT: 27% AngT: 19% DepT: 18% HelpT: 12% |

Single instrument |

Quality of life: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-C30; Thyroid supplementary questionnaire; Single screening question for fear of recurrence and fear of recurrence inventory. |

None | None | None |

| 14, Reis-Pina, (2017)41 | Predictor variable measure | ≥4 |

NPC present: DT: 58.3%, AnxT: 71.7% DepT:70%, AngT:61.7% HelpT:55.8%;

NPC absent: DT:55%, AnxT:73.7%, DepT:78.1%, AngT:56.6%, HelpT:56.6% |

Combination | ECOGS, BPI, CAGE alcohol questionnaire, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, HADS. | None | None | None |

| 16, Sanchez-Birkhead, (2017)42 | Screening | n.a. |

DT: 4.14 (n = 44) AnxT: 2.92 (n = 39) DepT: 2.65 (n = 40) AngT: 2.87 (n = 40) HelpT: 2.48 (n = 47) PanicT: 1.65 (n = 37) On average mild levels, except for DT. Depending on the measure, up to 21.3% women indicated emotional distress that would likely warrant intervention. |

Comparison | Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System, “My own health report,” Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics. ET was expanded by one additional thermometer for panic based on community input. | None | None | The specific ET domains augment the data in the DT by capturing more specific types of emotions. The thermometers had 10% item nonresponse, possibly due to the order of survey placement. |

| 17, George, (2018)43 | Outcome measure | n.a. |

Choice DT:2.41; AnxT:2.59 DepT:1.64; AngT:1.00 ET QoL:6.63 ET score:1.91

No Choice DT:2.18; AnxT:2.51 DepT:1.4; AngT:0.97 ET QoL:6.70; ET score:1.80

No art DT:2.26; AnxT:2.58 DepT:1.18; AngT:0.92 ET QoL:6.39; ET score:1.72 |

Combination |

State-trait Anxiety Inventory, Sense of control and/or influence instrument, self-reported pain, QoL. |

None | None | None |

- Abbreviations: AngT, anger; AnxT, anxiety; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CC, Concerns Checklist; CG, control group; DepT, depression; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV; DT, distress thermometer; ECOGS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale; ET, emotion thermometer; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy-General; GI, gastrointestinal; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HelpT, need for help; ID, identification number; IG, intervention group; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NPC, Neuropathic pain component; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSI, predictive summary index; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation; se, sensitivity; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey-36; SMW, standardized mean weight; sp, specificity.

- a Other distress screening instruments used in survey in combination with ET, but no direct comparison with ET.

- b ET results were compared to results of other distress screening instruments.

- c ET was the only tool used to screen for distress.

Distress levels were assessed mostly in patients (12 of 13), and one study described survivors.42 Distress was measured in cancer patients with a mean age greater than 50 years in most populations (12 of 13) and predominantly in females (3 of 13 all-female; 7 of 13 greater than 50% female; 2 of 13 all-male; and 1 of 13 gender unreported). Most studies were conducted in Europe (n = 11),24, 25, 31-34, 37-41 and four were conducted in the United States,27, 35, 42, 43 one in Brazil,36 and one in Malaysia.26

Studies most commonly used a cross-sectional study design (13 of 17). We found three randomized controlled trials (RCTs)32, 33, 43 and one study with quasi-experimental cohort analytic design.39 Some studies (5 of 13) included different diagnoses (lung, breast, gastrointestinal, prostate, and thyroid cancers and head and neck tumors), but overall breast cancer was the most frequent diagnosis (6 of 13).

3.3 Study quality

Among the six quality criteria, sample characteristics (representativeness, information available on sample, and sample size) had the highest variability (strong, 3 of 17; moderate, 7 of 17; and weak, 7 of 17) (Tables S1 and S2). Most publications (14 of 17) investigated a study population likely to be representative of their target population; however, the majority of included studies did not present a nonresponder analysis comparing participants and nonparticipants of the studies, and, thus, there are remaining concerns on nonresponse bias. Sample sizes (n) varied between good (n > 100, 11 of 17), moderate (n: 50-100, 3 of 17), and weak (n < 50, 3 of 17). The selected study design was appropriate for the outcome of interest in all studies. All publications displayed strong methodology including controlling for confounders in the analyses of their study aims (general rating). Four studies controlled for confounders with respect to the ET (ET rating). All studies used appropriate statistical analysis methods and reported internally consistent results. All publications except one addressed study limitations. The ET was mostly administered through survey questionnaires (16 of 17). Among the 12 screening studies, distress was mainly quantified using the recommended cutoff of greater than or equal to 4 (7 of 12), while the other five screening studies used continuous scores. The ET rating yielded a global rating of six studies with strong global quality (35%), 10 with moderate (59%), and one with weak quality (6%). The general rating resulted in nine studies (53%) with a strong global rating and eight studies (47%) with a moderate one. No study was considered to be of weak quality.

3.4 Validity of the ET

Four of five validation publications24, 25, 27, 31 were from research groups including Alex J. Mitchell, who designed the ET in 2007 (Table 1). Three of these four evaluated different aspects of the ET in 130 cancer patients in the United Kingdom.24, 25, 31 The first publication reported on the design and validation of the ET.24 Validation of distress was achieved using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) total score and by testing different cutoffs on all thermometers. Almost 70% of the participants scored greater than or equal to 4 on any of the five dimensions of the ET. Of these, 54.4% would have been recognized using the DT alone. Of those scoring below the DT cutoff (greater than or equal to 4), more than half recorded emotional distress on at least one other emotion domain of the ET.24 To assess distress, the optimal thermometer against the total HADS score (cutoff greater than or equal to 15) was the AngT with a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 92%.24 Through expansion of the emotion domains, the ET detected a larger proportion of people with distress who would otherwise have remained undetected.24 Consequently, in order to investigate which combination of the thermometers would be optimal for the detection of depression, anxiety, or distress, the same patient population was used in another study.25 Results showed that against the total HADS score, the combined use of the DepT, AngT, and HelpT had a higher accuracy to correctly identify the distressed (86% compared with 76% with the DT alone).25 The authors concluded that a combination of thermometers such as the DepT, AngT, and AnxT was superior to any single thermometer, including the DT, for the assessment of distress and anxiety.25 In situations where “any significant emotional difficulty” is looked for, it is unlikely that one thermometer would be sufficient, and thus the ET is recommended. For depression itself, one single thermometer, the DepT, was optimal on its own, hence a single thermometer to screen for depression might suffice.

In order to validate the HelpT, the ET was compared with the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (Brief-PHQ-2) in combination with a simple help question “Do you want help for emotional or psychological concerns at this stage?” in another study.31 The HelpT was able to measure the desire for help, correctly identifying 80% of the participants with a need for help with cutoff greater than or equal to 3 on the HelpT. Using the HelpT gave valuable information, which was not achieved by mood screening only, and showed that the desire for further assistance was prevalent even in those who did not score highly on measures of psychological symptoms.31 Subsequently, these findings supported the inclusion of the HelpT.31

The fourth publication was performed in the United States, assessing the accuracy of an extended ET version (additional: duration of illness, burden, and Concerns Checklist) in a sample of 64 patients.27 Each thermometer of the ET separately yielded an accuracy higher than 82% against the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Results emphasized the ET's good-to-excellent utility score and underlined its usefulness as an acceptable screening tool.27 They advised cancer physicians and providers to employ the ET for initial screening to comply with the new standard of care in distress screening.44 The ET was equally acceptable to patients and health professionals and took less than 2 minutes to complete.24, 25, 27

A fifth publication validating the ET was performed in Singapore with 315 cancer patients.26 Using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) as a gold standard, the study detected good criterion validity for the ET, as well as positive correlations between HADS and ET.26

In examining the validation of the ET where researchers used different thresholds to identify cutoffs for clinically relevant distress, we found that the overall results suggest a cutoff greater than or equal to 4 for all thermometers of the ET to detect distress24-27 and need for help.31

After validation, researchers recommended the ET as a valid and reliable instrument.26 They pointed out the advantage the ET offered by allowing patients to fully understand the symptoms they were asked to rate, instead of only using the broad term of distress. Furthermore, they highlighted the ET's good criterion validity.26

3.5 Application of the ET

The remaining studies (12 of 17) applied the ET with varying purposes. Primarily, the ET was used as an outcome measure (6 of 12),32-34, 36, 39, 43 as a predictor variable measure (3 of 12),37, 38, 41 and for screening (3 of 12).35, 40, 42 Most of them adhered to the recommended cutoff (greater than or equal to 4; 7 of 12)33-35, 37, 38, 40, 41 (Table 1).

The ET was applied as an outcome measure in three RCTs,32, 33, 43 a study with quasi-experimental analytic cohort design,39 and two cross-sectional studies.34, 36 The first RCT evaluated the effect of an intervention using music therapy and emotional expression to lower negative emotions during chemotherapy treatment in an RCT with 62 patients in Italy.32 This study applied the ET as a single instrument preintervention and postintervention. The second RCT conducted in Portugal assessed emotional regulation, perception, and satisfaction with social support. This was done in a mixed diagnoses sample of 70 patients suffering from cancer-related fatigue during radiotherapy through an extended version of the ET (additional: duration of illness and burden).33 This study used the ET only in the beginning of the study to determine patients' study inclusion. The third RCT examined whether placing artwork in line of vision of 169 hospitalized cancer patients improved patient outcomes and satisfaction and whether having a choice in the art selection made a difference.43 They used a custom-made version of the ET (additional: quality of life instead of the HelpT) several times during patients' hospital stay. A quasi-experimental cohort analytic study assessed the effectiveness and acceptance of and satisfaction with guided chat groups in psychosocial aftercare with 44 outpatients after prostatectomy in Germany.39 This study used the ET preintervention and postintervention.

A first cross-sectional study measured treatment burden as an outcome in 30 patients with very low-risk prostate cancer in Brazil using the ET in combination with other screening measures.36 A second, Romanian study including 800 patients34, 38 applied the ET with other screening measures to assess how distress and well-being depend on demographic variables.34

Other publications used the ET as a predictor variable measure. One study based on the same Romanian sample as the previous study analyzed whether their distress level, assessed by the ET alone, would predict satisfaction with intimate life.38 Two publications, based on a sample of 371 Portuguese patients,37, 41 examined whether distress levels were associated with pain intensity in patient groups with different cancer diagnoses.37, 41

The ET was used for screening in one study in the United Kingdom40 and two from the United States.35, 42 Using the ET as a single instrument, the UK study screened for distress in 169 patients treated for thyroid cancer.40 The two studies in the United States35, 42 used an extended ET (additional: panic thermometer, based on community members' input) in 48 Hispanic breast cancer survivors42 and applied the ET as a single instrument for distress screening in 149 surgical breast cancer patients.35

Within the studies, the majority applied the ET in combination with a variety of other screening measures, including measures for distress (7 of 12).33, 34, 36, 37, 39, 41, 43 Four publications applied the ET as a single instrument,32, 35, 38, 40 meaning that no other distress screening measures were used simultaneously. One study descriptively compared the ET with the Patient Reported Outcome Measure Information System (PROMIS) Global Scale and a health risk assessment named “My own health report.”42 They concluded that even though the PROMIS Global Scale yielded more complete data in comparison with the ET, the ET's emotional domains augment the data by capturing more specific types of emotions in survivors of breast cancer.42 Another study modified the Concerns Checklist to reflect breast cancer patients' specific concerns.35 Additionally, they examined the impact of distress screening on clinic visit time.35 The ET's implementation together with the Concerns Checklist did not impact clinic visit times. Furthermore, the specific Concerns Checklist questions allowed for a more comprehensive screening.35

4 DISCUSSION

We found few publications reporting on the use of the ET in individuals diagnosed with cancer. Nonetheless, the overall quality of the included studies was considered moderate to high.

Five studies validated the ET, and the others applied the ET with another purpose. The five validation studies demonstrate its consistent reliability and validity as a screening instrument. Its usefulness is highlighted by two screening studies.35, 42 Despite the ETs initial design as screening instrument, studies used it to measure outcomes or predictor variables. The application of the ET may depend on the individual research question and study aim. Using it to measure a certain outcome or predictor variable is acceptable.

Only four of the exploratory studies investigating distress used the ET as a single instrument. The majority of these studies used the ET in combination with other screening measures, including other measures for distress. Additionally, we observed that many studies hold on to the use of the DT for distress screening in combination with laborious screening measures, such as, but not limited to, HADS and BDI-II (14 and 21 items, respectively). In general, time-consuming and long assessments may impose additional stress on this specific vulnerable population. Validation against HADS and BDI-II shows comparable accuracy.24, 25, 27 Completion of these takes at least 5 to 7 minutes without assessing perceived need for help. In contrast, the ET only takes up 1 to 2 minutes in assessing the full range of emotions and unmet needs through the HelpT. Nevertheless, choice and length of screening or assessment instruments strongly depend on the purpose of the study. Meanwhile, for psychological distress screening and needs assessment, using the ET in research would suffice.

Prompt and accurate assessment of clinically relevant diagnoses can be achieved by using the ET as an initial screening instrument. Screening with the ET includes the evaluation of needs for possible subsequent referral to support services. This did not have a negative impact on clinic visit time.35 A study reviewing policy literature and research on psychological distress screening underlined not only the necessity for psychological screening but also the importance of assessing the need for help.45 More specifically, they recommend to not only focus on screening accuracy but also provide assistance through referrals when unmet needs are detected. This recommendation is in line with other findings where the desire for help was prevalent even in those who did not score highly on measures of psychological symptoms (HADS and DT) and thus made the introduction of the HelpT imperative.31 The ET has been shown to be accurate and valid, but difficulties in assessing support needs would be alleviated with the simple HelpT. To reduce the imposed effects of distress, help should be provided and further referrals considered.

Even though comparisons between populations is relevant in research, screening based on comparative needs should not be the only driving force.45 There is agreement on the crucial part of screening for distress and the identification of those in need for help during the cancer trajectory.

Less than half of the studies reported high levels of distress in participants. This might be related to the population age of the included studies. Even though research shows that older survivors of cancer have higher distress compared with the respective norm population,6 in general, the proportion of those with distress decreases with increasing age.6 Despite inclusion of young adults in the study populations (age range: 18-92),26, 33-35, 38, 42 mean age was overall greater than 50 years. This finding strongly indicates a lack of published literature on screening with the ET in younger patients and survivors, especially considering that no language or time frame limitations were applied in order to maximize the search output.

4.1 Study limitations

The systematic search found only few publications reporting on the use of the ET, resulting in 17 included studies. However, the ET is a relatively new instrument, designed in 2007. It is expected that further studies will be published in the future. A potential bias regarding recommendations could be the inclusion of the four validation studies of the ET's development group and few studies using the ET for its original screening purpose. Nevertheless, usability and advantages of the ET were additionally emphasized by other publications. Another limitation might be the use of a nonvalidated study quality assessment tool. However, while there is wide variability across quality evaluation tools,46 tools for quality appraisal of cross-sectional studies are rare.29 Therefore, many researchers, like us, use a self-created set of quality appraisal questions. This allowed to have a quality assessment tool specifically tailored to the use of our review, assessing the consideration of confounders for study aims and ET analyses.

4.2 Clinical implications

An important step to improve health provision was the establishment of guidelines for distress screening,5, 15 for instance, with the ET.

Although not many studies have been published so far, the ET has generated consistent findings and was shown to be an instrument with good criterion validity and reliability for the detection of emotional distress.24-27 Its accuracy is comparable with HADS and BDI-II, and its implementation is highly encouraged by validation studies.24-27 Our review also showed high acceptance by patients.24, 27

Additionally, using the ET as outcome or screening measure allows a timely and accurate assessment of distress34 without impacting clinic visit times.35 Hence, its implementation in time-constrained situations such as the clinical setting can further support high quality care. Compared with the DT in which overall distress is assessed, the ET enables patients to better understand and rate their emotional symptoms.26 This helps improve the available information by capturing the experienced emotions in more detail.42 To expand the existing literature on the ET's validity and applicability, especially as a screening instrument, further research should focus on the implementation of “routine” screening using the ET to screen for psychological short- and long-term impact of a cancer diagnosis. If necessary, in-depth conversations and profound clinical interviews should follow distress screening and patients and survivors referred to psychological care when needed. Furthermore, the use of the ET needs to be investigated in younger patients and young survivors. Consequently, the quality of follow-up care and survival may benefit from screening with the ET.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of the ET is to screen for emotional distress while giving the opportunity to pinpoint more specific issues and need for help in the clinical setting. Its prompt application is promising for research. In conclusion, in adult cancer patients, the ET was shown to be a valid and reliable tool to screen for distress, yet its screening purpose needs more confirmation from additional application studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Cancer Research Switzerland (grant no. KFS-3955-08-2016).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.