Management of diabetic neuropathy: the ADA's latest statement fleshes out NICE guidance

The American Diabetes Association has recently published its position statement on the prevention and management of diabetic neuropathy.(Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–54.)1

As Steve Chaplin here reports, it draws on recent reviews, notably several from the Toronto Consensus Panel on Diabetic Neuropathy, and is a summary of current thinking that adds some flesh to the bare bones that is NICE guidance.2-5

Scope

The ADA focuses on distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSPN) and, of the autonomic neuropathies, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN). This reflects the strength of evidence for the most common neuropathies and emphasises the lack of research into its many other manifestations (Box 1). Diabetic neuropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Screening can pick up the signs and facilitate early intervention but people with pre-diabetes are also at risk of developing neuropathies that are similar to diabetic neuropathies. (NICE prefers ‘at high risk of developing diabetes’ rather than pre-diabetes but the latter is an increasingly popular term.) Treatment can reduce complications and improve symptoms and quality of life, but there is little evidence that nerve damage can be reversed.

Box 1. Diabetic neuropathies and non-diabetic neuropathies common in diabetes1

- Distal symmetrical polyneuropathy

- – Primarily small-fibre neuropathy

- – Primarily large-fibre neuropathy

- – Mixed small- and large-fibre neuropathy (most common)

- Autonomic

- – Cardiovascular:

- Reduced heart rate variability;

- Resting tachycardia;

- Orthostatic hypotension;

- Sudden death (malignant arrhythmia)

- – Gastrointestinal:

- Diabetic gastroparesis (gastropathy);

- Diabetic enteropathy (diarrhoea);

- Colonic hypomotility (constipation)

- – Urogenital:

- Diabetic cystopathy (neurogenic bladder);

- Erectile dysfunction;

- Female sexual dysfunction

- – Sudomotor dysfunction:

- Distal hypohydrosis/anhidrosis;

- Gustatory sweating

- – Hypoglycaemia unawareness

- – Abnormal pupillary function

- – Cardiovascular:

- Isolated cranial or peripheral nerve (e.g. central nerve III, ulnar, median, femoral, peroneal)

- Mononeuritis multiplex (if confluent may resemble polyneuropathy)

- Radiculoplexus neuropathy (lumbosacral polyradiculopathy, proximal motor amyotrophy)

- Thoracic radiculopathy

- Pressure palsies

- Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy

- Radiculoplexus neuropathy

- Acute painful small-fibre neuropathies (treatment-induced)

Prevention

Far better than attempting a cure, good-quality glycaemic control can prevent or delay diabetic neuropathy but is not easy to achieve. The outlook for people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is better than in type 2 (T2D). Clinical trials have shown that tight glycaemic control – with a target HbA1c of ≤45.4mmol/mol (6.3%) – reduces the risk of DSPN by 78%. NICE's target HbA1c of 48mmol/mol (6.5%) or lower is equally ambitious – perhaps overly so, because only 30% of people with T1D and 66% of those with T2D in England have achieved it in real-world clinical practice.6

Aiming for a similar target in patients with T2D delivers a risk reduction of only 5–9%. The reasons for this difference are not known but probably include the attenuation of glycaemic control by multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, weight gain and hypoglycaemia, plus the cumulative effects of several years of asymptomatic hypoglycaemia.

Likewise, tight glycaemic control reduces the risk of CAN by almost a third after 14 years in people with T1D whereas, with one exception, clinical trials have not shown a comparable benefit in T2D. The exception was the Danish Steno-2 trial of targeted, intensified, multifactorial intervention which reported a 60% reduction in the risk of CAN after nearly eight years.7

Steno-2 was one of several trials suggesting that intensive lifestyle change is beneficial; one even demonstrated nerve fibre regeneration in people with T2D after exercise compared with nerve fibre loss with standard care.8 Which form of exercise and which diet is best, and whether the two must be combined, are all unknown.

The ADA recommends early optimisation of glycaemic control to prevent or delay the development of DSPN in everyone with diabetes. This will also prevent or delay CAN in people with T1D, whereas a multifactorial approach is recommended for those with T2D.

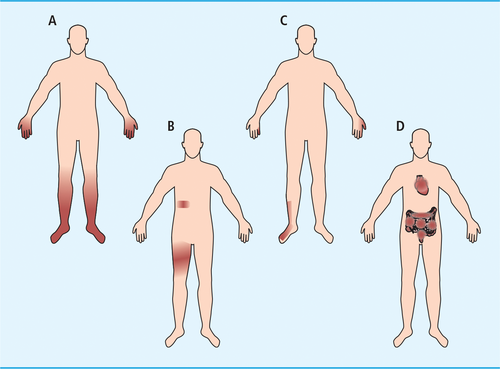

Chronic distal symmetric polyneuropathy

Defined as ‘the presence of symptoms and/or signs of peripheral nerve dysfunction in people with diabetes after the exclusion of other causes’, this accounts for 75% of all diabetic neuropathies. (Figure 1.) Although its pathogenesis is still unknown, DSPN is believed to result from damage to nerve cells from oxidative and inflammatory stress in an environment altered by metabolic dysfunction. Estimated prevalence in people with T1D is 20% after 20 years but the outlook is worse in T2D: 10–15% may be affected at the time they are diagnosed and around half may have developed DSPN after 10 years. This is not a problem solely of older age – rates in young people are similar – nor is it confined to overt diabetes: 10–30% of people described as having impaired glucose tolerance, pre-diabetes or metabolic syndrome may have DSPN, ‘especially the painful small-fibre neuropathy subtype’.1

DSPN is important because of its symptoms and complications – diabetic foot, Charcot neuroarthropathy, and falls and fractures. Pain and dysaesthesia due to small-fibre damage are often the first symptoms. Neuropathic pain, typically burning, lancinating, tingling or shooting and worse at night, occurs in a quarter of people with DSPN and may be what drives many to seek medical help. Pain and the associated paraesthesia, hyperalgesia and allodynia can have a significant impact on wellbeing and quality of life. By contrast, loss of large-fibre function does not cause pain – quite the opposite, in fact. Numbness results in the loss of protective sensation, a risk factor for foot ulceration.

Assessment

The ADA says all patients should be assessed for DSPN at the time of diagnosis of T2D, five years after a diagnosis of T1D, then at least annually in both cases. Clinicians should also consider screening patients with pre-diabetes who have symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.

The statement describes simple clinical tests to assess nerve function with a level of detail beyond that which NICE provides. Small-fibre function should be assessed by pinprick and temperature sensation; large-fibre function by vibration perception (using a 128Hz tuning fork), proprioception and ankle reflexes. Light-touch perception should be assessed using a 10g monofilament bilaterally on the dorsal aspect of the big toe; this is mainly of value in detecting more advanced neuropathy and should be carried out annually to identify patients at increased risk of ulceration and amputation. (This is not the approach used to assess a foot at high risk of ulceration, which entails testing the first, third and fifth metatarsal heads and plantar surface of distal hallux on each foot.)

The presence of typical symptomatology and symmetrical distal sensory loss in a patient with diabetes is highly suggestive of DSPN. Because so many patients have no symptoms, the diagnosis may have to rely on the examination alone supported by signs such as a painless ulcer. Neuropathy may be non-diabetic in origin and other causes (Box 2) should be excluded. The ADA states that these steps are sufficient for a diagnosis and electrophysiological testing or referral to a neurologist is rarely necessary. Exceptions to this rule include atypical clinical features (such as motor neuropathy more marked than sensory neuropathy, asymmetrical presentation or rapid progression), an unclear diagnosis or a possible alternative aetiology.

Box 2. Other possible causes of distal neuropathy1

- Metabolic disease

- – Thyroid disease (common)

- – Renal disease

- Systemic disease

- – Systemic or non-systemic vasculitis

- – Paraproteinemia (common)

- – Amyloidosis

- Infectious

- – HIV

- – Hepatitis B

- – Lyme disease

- Inflammatory

- – Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy

- Nutritional

- – Vitamin B12 (usually malabsorption rather than deficiency)

- – Post-gastroplasty

- – Pyridoxine

- – Thiamine

- – Tocopherol

- Industrial agents, drugs, and metals

- – Acrylamide

- – Organophosphorous agents

- – Alcohol

- – Amiodarone

- – Colchicine

- – Dapsone

- – Vinca alkaloids

- – Platinum

- – Taxol

- – Arsenic

- – Mercury

- Hereditary

- – Hereditary motor, sensory, and autonomic neuropathies

In England and Wales, commissioners should offer annual foot assessment via a podiatrist-led foot protection service to prevent foot problems and a multi/interdisciplinary foot protection service to deal with problems the former cannot manage.5 The National Diabetes Foot Care Audit suggests this is not being achieved in many places, with only 60% of CCGs and health boards able to provide information about their service, of which one-quarter admitted they had no foot protection service in place.9 Possibly, the situation is no better in the US. The ADA describes its recommendations for assessment as simple and comprehensive but it acknowledges the value of a 3-minute diabetic foot exam that requires no equipment and provides education and advice on preventative foot self-care. It is intended for physicians and other health professionals who may only have 15 minutes for a complete annual diabetes review.10

Pain management

NICE recommends a choice between amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin or pregabalin as initial treatment for neuropathic pain and, if one option fails, sequential trials of the others. The opioid tramadol should be used only if acute rescue therapy is needed; capsaicin cream is an option for localised neuropathic pain.4

The ADA notes that most of the evidence for drug treatment comes from trials that included all types of neuropathic pain, not solely DSPN, and its guidance is slightly more restrictive. It recommends pregabalin or duloxetine as initial therapy, with gabapentin a secondary option. Tricyclic antidepressants and venlafaxine are effective but unlicensed for this use and associated with a high risk of adverse effects. If first-line therapy fails, alternative options and combinations should be tried. Opioids, including tramadol and tapentadol, are not recommended as first- or second-line therapies. Patients with pain despite one of the recommended treatments should be referred to a pain specialist before a strong opioid is prescribed.

Preventing falls

Many factors conspire to increase the risk of falls in those with diabetic neuropathy. DSPN compromises balance through loss of proprioception and weakness, leading to unsteady gait. Physical difficulty due to neuropathic pain and the adverse effects of its treatment on cognitive function, combined with polypharmacy, cause drowsiness, dizziness and blurred vision and add to the impairments associated with older age. It is thus important to assess gait and balance to assess the risk of falls.

Psychosocial factors

DSPN is a risk factor for depression, which in turn is associated with unsteadiness, and pain causes anxiety. The ADA suggests two strategies specifically to improve quality of life: assess the effects of DSPN on quality of life to improve adherence and response to neuropathic pain treatment, and prescribe duloxetine, pregabalin or gabapentin. Two tools may be useful: Neuro-QoL and QOL-DN.

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy

With a prevalence profile similar to DSPN, CAN is uncommon in people newly diagnosed with T1D but affects at least 30% after 20 years. In T2D, it is present in 60% of people after 15 years. Although prevalence increases with age, 20% of young people with diabetes may have CAN, with young women and individuals with poor glycaemic control particularly at risk. CAN also occurs in people with impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome.

CAN is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) mortality, arrhythmia, silent ischaemia, any major CV event and myocardial dysfunction. After adjusting for other CV risk factors, it is associated with a >2-fold increased risk of all-cause and CV death. It is also a predictor of progression of diabetic nephropathy and chronic kidney disease. Evidence suggests that intensifying control of blood glucose and blood pressure in people with CAN may increase the risk of a CV event.

Diagnosis and management

CAN may be asymptomatic, detectable only by decreased heart rate variability with deep breathing. Symptoms – including light-headedness, weakness, palpitations, faintness and syncope, all of which occur on standing – are a late manifestation and correlate poorly with the degree of neuropathy.

Patients with microvascular and neuropathic complications, possibly including those with hypoglycaemia unawareness, should be screened for CAN. Other causes (comorbidities, drug therapy) should be excluded. Management involves non-specific measures to optimise health and hopefully slow progression, such as improving glycaemic control and reducing risk factors.

Symptomatic treatment of orthostatic hypotension includes physical activity (to avoid deconditioning) and volume repletion. If this is insufficient, pharmacological options include low-dose fludrocortisone and the alpha-1 agonist midodrine, though there is a risk of supine hypertension with both. US prescribers also have access to the norepinephrine prodrug droxidopa;11 marketing authorisation in Europe has not been sought to date.

Other autonomic neuropathies

Neuropathy may also cause bladder dysfunction and sexual dysfunction in men and women. Screening should be considered for people with erectile dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, lower urinary tract symptoms or repeated urinary infection. The ADA does not recommend routine screening for sudomotor dysfunction, which causes dry skin, anhidrosis or heat intolerance.

References

References are available in Practical Diabetes online at www.practicaldiabetes.com.