Ocular venous occlusion in pediatrics: Should thrombophilia investigation and anticoagulant treatment be initiated?

Abstract

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) and superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis (SOVT) are rare diseases in the pediatric population; however, the ophthalmic and neurologic morbidity are significant. As published data are scarce for these conditions, we present our experience with pediatric ocular venous thrombosis in four patients, and discuss recommended management for evaluation and treatment. We suggest performing thrombophilia workup for all pediatric patients with RVO or SOVT. In patients with thrombophilia risk factors or patients with additional thrombi, we highly recommend initiating anticoagulation therapy. There is a need for more research in order to determine the optimal management strategy.

Abbreviations

-

- APLA

-

- antiphospholipid antibodies

-

- LMWH

-

- low molecular weight heparin

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

1 INTRODUCTION

Thrombosis of the ocular venous system may present as retinal vein obstruction (RVO) or superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis (SOVT). Both conditions are extremely rare among children, only 10%–15% of RVO patients are younger than 40 years.1, 2 The commonest presentation is sudden, unilateral, painless loss of vision.3, 4 RVO diagnosis relays on ophthalmic evaluation. Fluorescein angiography and/or optical coherence tomography (OCT) are often used to confirm the diagnosis during follow-up.5-7 Traditional risk factors in adults include advancing age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and glaucoma.8-10 Central RVO (CRVO) in children is often associated with either local compression or inflammation, or a systemic predisposition for thrombosis.11 The contribution of genetic thrombophilia to the occurrence of RVO is yet to be fully elucidated,12 and the role of anti-thrombotic therapy is not established as well.

The superior ophthalmic vein drains the central retinal vein and communicates directly to the cavernous sinus. SOVT is extremely rare in the general population (incidence of three to four cases per million per year).13 It may present with eyelid swelling, proptosis, motility impairment, or vision loss.14 SOVT is caused by altered venous blood flow resulting from stasis, due to trauma or hypercoagulability (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome or sickle cell anemia).13 In contrast to RVO, SOVT can be detected on post-contrast computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Anticoagulant therapy is usually initiated.13, 14

We hereby present our single-center experience with pediatric ocular venous occlusion, including retinal and ophthalmic veins. We discuss the etiologies, thrombophilia workup, treatment, and outcomes.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Patients

Our tertiary referral institute provides care for rare thrombotic disorders. Our study was approved by the institutional ethical committee in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

In this retrospective study, MDclone platform was used for extracting patient data according to their given diagnoses. Extraction of all patients aged 0-18 years with documented retinal vein occlusion/thrombosis and/or ophthalmic vein occlusion/thrombosis diagnosed and treated during the study period 2012–2022. Following extraction of patients a manual review and description of the data was performed.

All patients underwent thrombophilia workup (levels of protein C, protein S, antithrombin, homocysteine, genetic detection of factor V Leiden (FVL) and prothrombin mutation G20210A, and antiphospholipid antibodies [APLA]) as part of our routine investigation for thrombosis in unusual sites.

3 RESULTS

- Patient 1 born prematurely at 32 weeks of gestation, underwent surgery for bilateral congenital cataract. Following surgery, he suffered from left retinal detachment and left renal vein thrombosis, for which he was treated with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for 6 weeks. Thrombophilia workup found homozygousity to FVL. At age 7.5 years, upon ophthalmologist evaluation, he was diagnosed with left hemiretinal vein occlusion. Treatment was initiated with LMWH for 6 months, followed by rivaroxaban indefinitely.

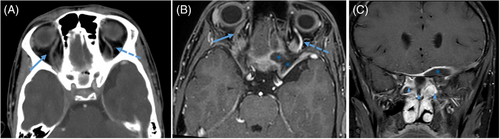

- Patient 2 presented with sinusitis and right periorbital cellulitis. MRI demonstrated right SOVT and partial right cavernous sinus thrombosis (Figure 1). Thrombophilia workup was negative. Surgical intervention for debridement of the infected tissue was followed by heparin and LMWH treatment, following rivaroxaban therapy for 6 months. Repeated MRI demonstrated full resolution of findings.

| Patient number | Age at diagnosis (years), and gender | Provocation | Diagnosis | Thrombophilia workup | Anticoagulation treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7, M | Glaucoma, S/P retinal detachment, and silicone laser inraocular lens removal | Hemiretinal vein occlusion via ophthalmologic examination | Homozygous FVL (known) | LMWH followed by rivaroxaban | Left eye blindness, anticoagulation ongoing indefinitely |

| 2 | 14, M | Ethmoidal sinusitis | MRI | No findings | Heparin, LMWH followed by rivaroxaban | Complete resolution of SVT and ophthalmic thrombosis on MRI at 3 months, treated for 6 months |

| 3 | 12, M | Osteosarcoma, chemotherapy, central venous catheter-associated thrombus | OCT, MRI | No findings | LMWH | Complete resolution, treated for 1 year (until central catheter was removed) |

| 4 | 17, F | None | OCT | Heterozygous FVL, heterozygous MTHFR | None | Complete resolution within days |

- Abbreviations: FVL, factor V Leiden; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

- Patient 3, during chemotherapy for osteosarcoma, presented with acute deterioration of right eye vision, 1 week after manipulation of his central venous line (CVL). Funduscopy demonstrated small macular hemorrhages and vascular congestion, OCT confirmed CRVO, and ultrasound of the right arm demonstrated CVL thrombosis. Thrombophilia workup was negative. He was treated with LMWH throughout his oncologic treatment. Complete resolution was noted as well as remission from osteosarcoma.

- Patient 4, previously healthy, presented with a sudden decrease in right eye vision. Ophthalmic evaluation demonstrated congestion of the venous ocular drainage, superficial parapapillar hemorrhages, and peri-foveal hemorrhages without edema, compatible with the diagnosis of CRVO. She did not receive anticoagulation treatment, due to rapid improvement of vision. However, following CRVO and diagnosis of FVL heterozygosity, she was advised not to use estrogen-containing oral contraceptives and to consult hematologist before future high-risk conditions.

4 DISCUSSION

We hereby present our experience with pediatric ocular venous thrombosis in four patients (Table 1). We discovered inherited thrombophilia in two patients with RVO as well as two acquired risk factors (active malignancy and sinusitis).

Data regarding thrombophilia in pediatric RVO and SOVT are scant. Overall, reported risk factors include: APLA,15-19 homocysteinemia, platelet over-responsiveness,9, 20 vasculitis, acute infections, inflammatory states, and optic pathway tumors.3, 11, 21-27 In some reports, more than one genetic abnormality was found in patients with RVO, suggesting synergistic interactions that may increase the risk.28

As for SOVT cases, infectious etiologies.29, 30 traumatic31 and idiopathic,32 have been reported. The rarity of these cases precludes the possibility to conclude the causality and correlation with these risk factors. Specifically, sinusitis is a known risk factor for sinus vein thrombosis, and in our patient, the thrombosis extended from the superior ophthalmic vein into the cavernous sinus, supporting the etiology underlying this case.33

Chen et al. support the systemic workup for hypercoagulable risk factors in RVO in patients younger than 40 years of age,2, 31 further supported by the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA).32 Conversely, Romiti et al. found that patients with RVO demonstrated similar prevalence of inherited and acquired thrombophilias as compared to controls.34 Their findings are supported by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, which recommends against thrombophilic evaluation, as it will not alter management or predict prognosis.35

While its etiology may be controversial, RVO could be considered as a thrombotic event. As the pediatric population (specifically, the non-hospitalized patients) does not have significant pro-thrombotic risk factors, the pathophysiologic role of thrombophilia might be more profound. Genetic thrombophilia may predict higher recurrence rates (patient 1), and suggest lifestyle accommodations (patient 4), it may affect duration of anticoagulation, as well as a need for additional treatments and provide the patients and families with an etiology.

In the majority of published cases, anticoagulation was given mainly to patients with APLA and genetic thrombophilia and when additional thrombi were found.18, 24, 36 Notably, the majority of RVO associated with APLA syndrome are reported in patients above the age of 10 years. In the literature, there were no reports of increased bleeding complications in pediatric patients treated with anticoagulation for RVO or SOVT. Among our patients, three-fourth had complete resolution and one patient had damage to his eye, not attributed to RVO. One patient did not receive anticoagulation due to rapid improvement and complete resolution. Of note: Lazo-Langner et al. and Squizzato et al. found that LMWH therapy in adults was associated with improvement of visual acuity.37, 38

The Italian Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (SISET) acknowledges that data on the efficacy of antithrombotic drugs for the treatment and prevention of RVO are inconsistent.39 For recent-onset RVO (up to 30 days) with a low risk of bleeding, they recommend treatment with LMWH, followed by anti-platelet treatment in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events.39 Bremond-Gignac et al., in their pediatric case series, suggest that low-dose aspirin therapy may be beneficial.9 In SOVT patients, anticoagulation treatment is common practice13; however, there are no established guidelines to date.

In conclusion, it is our practice in the pediatric population to perform a full thrombophilia workup to detect risk factors that may impact the future management of children in both RVO and SOVT. Thrombophilia screening affects not only the duration of treatment but also the management in future clinical situations, with increased thrombotic risk and implications on other family members.9, 40 Regarding anticoagulant therapy, case-by-case management is suggested. In patients with thrombophilia predisposition or patients with additional thrombi, we highly recommend initiating anticoagulation therapy. Due to the rarity of these clinical entities in the pediatric population, more research is required to determine the optimal management strategy.