Healthcare utilization and cost barriers among U.S. childhood cancer survivors

Abstract

Background

To evaluate healthcare utilization and cost barrier patterns among childhood cancer survivors (CCS) compared with noncancer controls.

Procedure

Using the 2014-2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, we identified CCS < 50 years and matched controls. We used chi-squared tests to compare characteristics between the two groups. Logistic regression analyses were used to assess the likelihood of having a checkup, receiving influenza vaccine, and experiencing healthcare cost barriers (being unable to see the doctor due to cost) during the past 12 months. Conditional models accounted for the matching.

Results

We included 231 CCS and 692 controls. CCS had lower household income (p < 0.001), lower educational attainment (p = 0.021), more chronic health conditions (p < 0.001), and a higher proportion of being current smokers (p = 0.005) than controls. Both groups had similar rates of having a checkup and influenza vaccine; however, a quarter of CCS experienced healthcare cost barriers compared with 13.9% in controls (p = 0.001; regression findings: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.72, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11-2.65). Compared with the youngest CCS group (18-24 years), CCS ages 25-29 years were five times more likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (aOR = 4.79; 95% CI, 1.39-16.54). Among CCS, current smokers were less likely to have a checkup (aOR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23-0.94). Uninsured CCS were less likely to have a checkup (aOR = 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14-0.75) and ∼8 times more likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (aOR = 8.28; 95% CI, 3.45-19.88).

Conclusion

CCS being 25-29 years, uninsured, or current smokers encounter inferior outcomes in healthcare utilization and cost barriers. We suggest emphasis on programs on care transition and smoking cessation for CCS.

Abbreviations

-

- aOR

-

- adjusted odds ratio

-

- BRFSS

-

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

-

- CCS

-

- childhood cancer survivors

-

- CCSS

-

- Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

1 INTRODUCTION

Half a million childhood cancer survivors are living in the United States (2020) with significant improvement in survival and other health outcomes.1 However, two-thirds of these survivors experience late physical and emotional effects from the treatment for their childhood cancer (e.g., chemotherapy and radiation), which increases their healthcare needs.2-4 It is important to understand long-term healthcare utilization and access among childhood cancer survivors (CCS) to facilitate timely public health programs,5 with the ultimate goal of improving clinical health outcomes and quality of life for this vulnerable population.

A few studies have investigated patterns of healthcare utilization, barriers to healthcare access, and their associated factors among CCS.6, 7 Cousineau et al. showed that insurance coverage for CCS was a key driver to seeking care from cancer specialists and primary care physicians.6 Using a large data set from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), Mueller et al. showed that health insurance increased the likelihood of outpatient care.7 Baedke et al. using the St. Jude Life data found that a quarter of CCS (24.8%, 985/3,964) reported “forgoing needed medical care in the last year due to finances.”8 This study accounted for age, sex, treatment era, treatment type, primary cancer types, and self-reported health perceptions. There are additional factors that may be related to forgone needed medical care but were not addressed in previous studies.

Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use9 has been widely utilized to assess relationships between healthcare utilization and predisposing, enabling, and need factors. This model suggests additional factors beyond those examined in previous studies may be related to forgone needed medical care. These additional factors may include marital status, residency as predisposing factors, employment as an enabling factor, and health risk behaviors (including smoking, binge drinking, and physical activity) and body mass index as need factors.9, 10

In this paper, we look for additional factors that may affect the use of healthcare by CCS. We used national survey data to evaluate healthcare utilization and cost barriers (i.e., having a checkup, receiving influenza vaccine, or experiencing healthcare cost barriers in the past 12 months) among U.S. CCS by themselves and in comparison with noncancer controls. Using a nationally representative data set has the potential to provide more generalizable findings. The inclusion of unstudied predictors of healthcare utilization and barriers would further knowledge on this topic.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data source

The Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an annual phone-based survey among U.S. residents aged ≥18 years. Each year, state health departments administer the core modules and state-selected optional modules. The core modules include questions about demographics, current health-related perceptions, conditions, behaviors, and chronic health conditions. Examples of the optional modules include cancer survivorship, caregiving, and adverse childhood experience. States can administer the same modules for multiple years.11 Random respondent selection is applied using random digit dialing on both landlines and cellphones.12 Data from the BRFSS are publicly available, have no individually identifiable information, and do not meet the requirement for the definition of human subjects research. Thus, our study is deemed exempt from further IRB review.

2.2 Study sample

Our sample included respondents aged < 50 years from states participating in the cancer survivorship module in the BRFSS from 2014 to 2019 (excluding 2015 when no state completed this module). If a given state repeated participation in the survivorship module over years, data for the year with the most CCS respondents from that state were used. We included survivors of a cancer diagnosed at age 20 years or younger and respondents without a history of cancer (i.e., the general population) as noncancer controls. CCS selected in our sample had only one cancer diagnosis recorded. We used the exact match method approach (1:3, based on age, race, sex, state, and year of survey) to select controls with the ultimate goal of addressing the selection bias. The ratio 1:3 for case:control was deemed sufficient because there was no extra benefit of using greater ratios.13, 14

2.3 Study design, outcomes, and covariates

In this cross-sectional study, our outcomes of interest were receiving influenza vaccine, having a checkup with a doctor (a checkup), and experiencing healthcare cost barriers for needed care (experiencing healthcare cost barriers, derived from response to the questions “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”). All of these outcomes concerned the respondents’ experience during the 12 months before the survey completion. We compared the prevalence rates of our outcomes between CCS and their matched noncancer controls. We included receiving influenza vaccine as an outcome because it is particularly crucial to those with underlying chronic conditions (including cancer) and it is administered frequently enough to become a marker monitoring healthcare-seeking behaviors.15 Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use9 (Supporting Information) guided our selection of covariates in the analyses. Our covariates included predisposing factors (age, race/ethnicity, sex, and residential geography); enabling factors (e.g., income, insurance at the time of survey, and residing in a Medicaid-expansion state); and need factors (including several clinical factors: being ever told to have diabetes, being ever told to have arthritis, being obese, and other chronic conditions, self-reported mental and physical health, and several health risk behaviors, e.g., smoking, binge drinking, and physical activity). We derived a composite index of chronic health conditions by summing the counts of the self-reported chronic conditions. We assessed these covariates to determine their association with healthcare utilization and cost barriers.

2.4 Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses that examined CCS among themselves and compared with their matched noncancer controls. We used chi-square tests to compare demographics, health risk behaviors, and chronic conditions. We used univariate conditional logistic analyses to examine separately the association of our outcomes with the covariates. We used multivariable conditional logistic regression analyses to assess the simultaneous effect of the covariates. Selection of the predictors based on the p-value < 0.20 was part of the model-building process used in the univariable analysis in accordance with Hosmer et al.16 and Bursac et al.17 If we deemed two or more covariates highly correlated based on intuition or statistical verification, we did not include all of these two or more highly correlated covariates simultaneously in multivariable models.18, 19 We used SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to analyze the data. All tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in the multivariable models.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

A total of 923 survey respondents were included in our final sample (231 CCS and 692 controls; Table 1 and Supporting Information) from 19 states (Supporting Information); most respondents were from the Midwest. CCS were primarily White (81.8%) and female (74.9%). The mean age at childhood cancer diagnosis was 15.5 years (standard deviation [SD], 4.9 years), and the median age was 17 years (range, 1−20 years). The mean length of time since diagnosis of the primary cancer was 18.2 years (SD, 9.4 years); and the median was 18 years (range, 1−45 years).

| CCS (N = 231) | Controls (N = 692) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Year, N (%) | 0.999 | ||

| 2014 | 82 (35.5) | 246 (35.6) | |

| 2016 | 70 (30.3) | 210 (30.4) | |

| 2017 | 53 (22.9) | 159 (23.0) | |

| 2018 | 11 (4.8) | 33 (5.0) | |

| 2019 | 15 (6.5) | 44 (6.0) | |

| Age groups, N (%) | 0.999 | ||

| 18-24 | 41 (17.8) | 122 (17.6) | |

| 25-29 | 39 (16.9) | 117 (16.9) | |

| 30-34 | 47 (20.4) | 141 (20.4) | |

| 35-39 | 39 (16.9) | 117 (16.9) | |

| 40-44 | 29 (12.6) | 87 (12.6) | |

| 45-49 | 36 (15.6) | 108 (15.6) | |

| Sex, N (%) | 0.991 | ||

| Male | 58 (25.1) | 174 (25.1) | |

| Female | 173 (74.9) | 518 (74.9) | |

| Region, N (%) | 0.999 | ||

| Northeast | 8 (3.5) | 24 (3.5) | |

| Midwest | 167 (72.3) | 501 (72.4) | |

| South | 29 (12.6) | 87 (12.6) | |

| West | 27 (11.7) | 80 (11.6) | |

| Education level, N (%) | 0.021 | ||

| aBelow college level | 76 (32.9) | 173 (25.0) | |

| Some college or technical school/college graduate | 155 (67.1) | 519 (75.0) | |

| Race, N (%) | 0.999 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 189 (81.8) | 567 (81.9) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13 (5.6) | 38 (5.5) | |

| Hispanic | 11 (4.8) | 33 (4.8) | |

| bOthers, non-Hispanic | 18 (7.8) | 54 (7.8) | |

| Employment, N (%) | <0.001*** | ||

| Employed/self-employed | 145 (62.8) | 531 (76.7) | |

| cOut of work/A homemaker | 34 (14.7) | 86 (12.4) | |

| dA student/Retired | 24 (10.4) | 46 (6.7) | |

| Unable to work | 28 (12.1) | 29 (4.2) | |

| Marital, N (%) | 0.008** | ||

| Married/A member of an unmarried couple | 117 (50.7) | 399 (57.7) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 45 (19.5) | 78 (11.3) | |

| Never married | 69 (29.9) | 215 (31.1) | |

| Average number of children in household, N (%) | |||

| One child | 54 (23.4) | 139 (20.1) | 0.570 |

| Two or more children | 93 (40.3) | 288 (41.6) | |

| No children | 84 (36.4) | 265 (38.3) | |

| Do you have any healthcare coverage? N (%) | |||

| Yes | 189 (81.8) | 615 (88.9) | 0.007** |

| No | 42 (18.2) | 77 (11.1) | |

| Income level, N (%) | < 0.001*** | ||

| < $15,000 | 39 (16.9) | 48 (6.9) | |

| $15,000 < $25,000 | 40 (17.3) | 93 (13.4) | |

| $25,000 < $35,000 | 18 (7.8) | 76 (11.0) | |

| $35,000 < $50,000 | 33 (14.3) | 80 (11.6) | |

| $50,000 or more | 79 (34.2) | 331 (47.8) | |

| Don't know/Not sure/Missing | 22 (9.5) | 64 (9.3) | |

| Health risk behaviors | |||

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.005** | ||

| eCurrent smokers | 70 (30.3) | 146 (21.1) | |

| Nonsmokers | 161 (69.7) | 546 (78.9) | |

| fDo you binge drink? N (%) | 0.143 | ||

| Yes | 46 (19.9) | 170 (24.6) | |

| No | 185 (80.1) | 522 (75.4) | |

| gActive physical activity level, N (%) | |||

| Active | 181 (78.3) | 554 (80.1) | 0.580 |

| Not active | 50 (21.7) | 138 (19.9) | |

| Self-reported mental health status, N (%) | |||

| Good | 173 (74.9) | 621 (89.7) | <0.001*** |

| Poor | 58 (25.1) | 71 (10.3) | |

| Days with poor mental health, N (%) | |||

| 1-13 days when mental health not good | 75 (32.5) | 222 (32.1) | <0.001*** |

| 14+ when mental health not good | 61 (26.4) | 98 (14.2) | |

| Zero day when mental health not good | 95 (41.1) | 372 (53.8) | |

| Days with poor physical health, N (%) | |||

| 1-13 days when physical health not good | 69 (29.9) | 185 (26.7) | <0.001*** |

| 14+ when physical health not good | 53 (22.9) | 60 (8.7) | |

| Zero day when physical health not good | 109 (47.2) | 447 (64.6) | |

| Chronic conditions | |||

| Body mass index, N (%) | 0.060 | ||

| Overweight/obesity | 134 (58.0) | 380 (54.9) | |

| Unknown | 8 (3.5) | 53 (7.7) | |

| Under/normal weight | 89 (38.5) | 259 (37.4) | |

| Number of chronic conditions | <0.001*** | ||

| > 1 | 102 (44.2) | 105 (15.2) | |

| None or 1 | 129 (55.8) | 587 (84.8) | |

| Length of follow-up | – | ||

| 26 years or more | 131 (56.7) | – | |

| ≤25 years | 100 (43.3) |

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

- a Below college level includes those who never attended school or only kindergarten, only elementary, only some high school and high school graduate.

- b Others, non-Hispanic includes Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Multiracial, and Others.

- c Out of work level includes those who were out of work for one year or more and those who were out of work for less than one year.

- d The group of a student and the group of being retired were combined in a category because those who are either students or retired are often out of the labor workforce. Another reason for this combination was the small sample size in each group.

- e Current smokers include those who smoked every day and those who smoked some days.

- f Males had five or more drinks on one occasion, females had four or more drinks on one occasion.

- g Active physical activity includes those who reported doing physical activity or exercise during the past 30 days other than a regular job.

CCS compared with controls were more frequent in lower average annual household income groups (p < 0.001), especially in the percentage of CCS versus controls earning $50,000 or more (34.2% vs 47.8%). CCS were less frequently employed or self-employed than controls (62.8% vs 76.7%) and more frequently unable to work (12.1% vs 4.2%, p < 0.001). Compared with controls, CCS had a lower proportion with some education at the college or technical school level (67.1% vs 75.0%, p = 0.021), a higher proportion being current smokers (30.3% vs 21.1%, p = 0.005). CCS compared with controls had a higher proportion who reported poor mental health for ≥14 days per month (26.4% vs. 14.2%, p < 0.001) and a higher proportion who reported poor physical health for 1 to 13 days (29.9% vs 26.7%) and ≥14 days (22.9% vs 8.7%) per month (p < 0.001). CCS also had higher proportions having had asthma, diabetes, arthritis, a depressive disorder, a stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or kidney disease. Overall, 44.2% of CCS had > 1 chronic health condition compared with 15.2% in controls (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

3.2 Comparison of healthcare utilization and cost barriers between CCS and controls

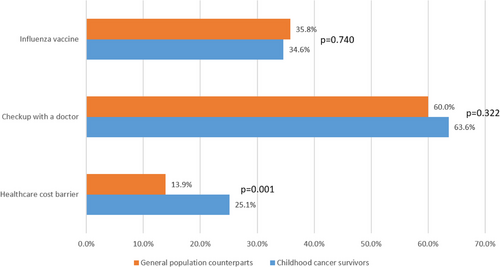

One-third (34.6%) of CCS had received influenza vaccine and two-thirds (63.6%) had a checkup. Controls had similar rates of having received the influenza vaccine (35.8%) and a checkup (60.6%). However, CCS experienced a higher proportion having healthcare cost barriers (25.1% vs. 13.9%, p = 0.001; Figure 1).

| Influenza vaccine | Yes/no answer to “During the past 12 months, have you had either flu vaccine that was sprayed in your nose or flu shot injected into your arm?”. |

| Checkup with a doctor | A Yes answer “Within the past year” to “About how long has it been since you last visited a doctor for a routine checkup?” |

| Other answers (“Within past 2 years, Within past 5 years, 5 or more years ago, Don't know/Not sure, Never”) were deemed No. | |

| Healthcare cost barrier | Yes/no answer to “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?” |

3.2.1 Univariate conditional logistic analyses on receiving influenza vaccine, having a checkup, and experiencing healthcare cost barriers among all samples

Respondents in lower income groups were more likely to have healthcare cost barriers (odds ratio [OR] range by group, 2.52−4.21) compared with those in the highest income group (p < 0.001). Compared with respondents with healthcare coverage, those without any coverage had lower likelihood of receiving influenza vaccine (OR = 0.14; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.07−0.28), lower likelihood of having a checkup (OR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16−0.43), and higher likelihood of experiencing healthcare cost barriers (OR = 6.04; 95% CI, 3.37−10.80; Table 2).

| Influenza vaccine | Checkup with a doctor | Healthcare cost barrier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Healthcare cost barrier Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

p value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| All sample | ||||||||

| Childhood cancer survivors | 0.95 (0.69-1.30) | 0.741 | 1.17 (0.86 - 1.59) | 0.323 | 2.08 (1.44 - 3.01) | <0.001*** | 1.72 (1.11-2.65) | 0.015 |

| Controls | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | * | |||

| Sex, N (%) | – | – | ||||||

| Female | 1.62 (1.17-2.25) | 0.004** | 1.62 (1.20-2.19) | 0.002** | 1.63 (1.05 - 2.52) | 0.031* | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Education Level, N (%) | 0.772 | 0.099 | ||||||

| aBelow college level | 0.30 (0.19-0.45) | < 0.001*** | 0.95 (0.66 - 1.36) | 1.76 (1.14 - 2.69) | 0.010* | 0.63 (0.36-1.09) | ||

| Some college or technical school/College graduate | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Employment, N (%) | ||||||||

| bOut of work/a homemaker | 0.50 (0.30-0.83) | 1.15 (0.71-1.86) | 1.15 (0.65-2.05) | 0.89 (0.46-1.74) | ||||

| A student/retired | 0.95 (0.51-1.78) | 0.060 | 1.36 (0.75-2.48) | 0.043* | 0.69 (0.29 - 1.62) | 0.044* | 0.42 (0.18-1.27) | 0.466 |

| Unable to work | 0.71 (0.35-1.47) | 2.92 (1.35-6.32) | 2.98 (1.32-6.72) | 0.64 (0.21-1.91) | ||||

| Employed/self-employed | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Marital, N (%) | ||||||||

| Never married | 0.89 (0.59-1.35) | 0.95 (0.63 - 1.42) | 1.51 (0.92-2.49) | 1.73 (0.97-3.11) | ||||

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.59 (0.35-1.00) | 0.146 | 0.81 (0.49 - 1.35) | 0.714 | 2.23 (1.23 - 4.02) | 0.018* | 1.08 (0.52-2.25) | 0.178 |

| Married/A member of an unmarried couple | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Do you have any healthcare coverage? N (%) | ||||||||

| No | 0.14 (0.07-0.28) | <0.001*** | 0.27 (0.16 - 0.43) | <0.001*** | 6.04 (3.37 - 10.80) | <0.001*** | 6.11 (3.04-12.28) | <0.001*** |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Income level, N (%) | ||||||||

| < $15,000 | 0.43 (0.23-0.80) | 0.82 (0.44-1.52) | 4.21 (2.09-8.48) | |||||

| $15,000-$25,000 | 0.49 (0.30-0.81) | 0.53 (0.33-0.85) | 3.58 (1.93-6.63) | |||||

| $25,000-$35,000 | 0.42 (0.23-0.75) | 0.32 (0.18-0.55) | 2.52 (1.24-5.13) | |||||

| $35,000-$50,000 | 0.59 (0.35-1.01) | 0.72 (0.42-1.24) | 3.45 (1.79-6.66) | |||||

| Don't know/not sure/missing | 0.49 (0.27-0.90) | 0.002** | 0.43 (0.24-0.77) | <0.001*** | 2.01 (0.89-4.56) | <0.001*** | ||

| $50,000 or more | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Health risk behaviors | ||||||||

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||||||

| s Current smokers | 0.43 (0.29-0.66) | <0.001*** | 0.53 (0.36-0.77) | 0.001*** | 2.93 (1.87-4.57) | <0.001*** | 2.16 (1.25-3.74) | 0.006** |

| Nonsmokers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Do you binge drink? N (%) | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 0.85 (0.58-1.26) | 0.425 | 0.61 (0.41-0.90) | 0.012* | 1.33 (0.83-2.13) | 0.244 | ||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Physical activity level, N (%) | ||||||||

| Not Active | 1.20 (0.80-1.80) | 0.377 | 0.98 (0.66-1.46) | 0.918 | 2.19 (1.35-3.54) | 0.001** | 2.00 (1.12-3.58) | 0.019 |

| Active | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Self-reported health status, N (%) | ||||||||

| Fair or poor health | 0.59 (0.36-0.96) | 0.035* | 1.27 (0.81-2.00) | 0.302 | 4.31 (2.56-7.25) | <0.001*** | 2.90 (1.46-5.75) | 0.002** |

| Good or better health | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Days with poor mental health, N (%) | ||||||||

| 1-13 days mental health not good | 1.04 (0.73-1.47) | 0.242 | 0.95 (0.67-1.34) | 0.844 | 2.96 (1.79-4.92) | <0.001*** | ||

| 14+ days mental health not good | 0.69 (0.43-1.10) | 0.88 (0.55-1.39) | 6.18 (3.46-11.06) | |||||

| Zero day mental health not good | Reference | Reference | Reference | – | – | |||

| Days with poor physical health, N (%) | ||||||||

| 1-13 days when physical health not good | 0.82 (0.56-1.18) | 0.414 | 1.02 (0.71-1.48) | 0.986 | 2.71 (1.83-4.03) | <0.001*** | ||

| 14+ days when physical health not good | 0.78 (0.48-1.28) | 1.04 (0.64-1.67) | 3.85 (2.38-6.24) | |||||

| Zero day when physical health not good | Reference | reference | Reference | |||||

| Chronic conditions | ||||||||

| Body mass index, N (%) | ||||||||

| Overweight/obesity | 1.16 (0.82-1.64) | 0.464 | 0.95 (0.686-1.35) | 1.34 (0.86-2.09) | 0.367 | |||

| Unknown | 0.79 (0.39-1.61) | 1.03 (0.51-2.06) | 0.952 | 0.98 (0.43-2.20) | ||||

| Under/normal weight | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||||||

| >1 | 0.75 (0.51-1.11) | 0.145 | 0.96 (0.66-1.41) | 0.845 | 4.41 (2.79-6.99) | <0.001*** | ||

| None or 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

- Models were adjusted for year of data, age, race/ethnicity, residency region, and number of children in the household.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

- a Below college level includes those who never attended school or only attended kindergarten, those who attended only elementary school or some high school, and those who were high school graduates.

- b Out of work includes those who were out of work for one year or more and those who were out of work for less than one year.

An educational attainment below college level, being divorced/widowed/separated, having no healthcare coverage, lower income, being physically inactive, reporting fair or poor health, having poor mental health for ≥1 day, having poor physical health for ≥1 day, and having > 1 chronic health condition were associated with increased likelihood of having healthcare cost barriers (OR range by covariate, 1.76-6.18, p < 0.05). Being current smokers was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving influenza vaccine or having a checkup and with a higher likelihood of experiencing healthcare cost barriers. CCS were more likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (OR = 2.08; 95% CI, 1.44−3.01) compared with controls (Table 2).

3.2.2 Multivariable conditional logistic analysis on experiencing healthcare cost barriers among all samples

CCS remained more likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.72; 95% CI, 1.11-2.65) compared with controls. Respondents without healthcare coverage had a six-fold likelihood to experience healthcare cost barriers (aOR = 6.11; 95% CI, 3.04-12.28). CCS being current smokers were twice likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (aOR = 2.16; 95% CI, 1.25-3.74). Because CCS had a much higher proportion of having multiple chronic health conditions than controls, the covariate of being a CCS and the count of chronic health conditions were highly correlated. Thus, our primary multivariable model excluded the latter. In a separate analysis including both covariates (Supporting Information), the count of chronic condition was statistically significant while the status of being a CCS was not.

3.3 Healthcare utilization and cost barriers among CCS

3.3.1 Having a checkup with a doctor

During the step of model selection, although the survey year and region were qualified covariates for the multivariable analyses based on their statistical significance in the univariate analyses on having a checkup (p < 0.20), we decided to include only region in the multivariable analysis. The reason was that these two were highly correlated for our sample selection method, which included only the one-year data of a given state if that state had multiple years of data. Among CCS, being a female aOR = 3.03; 95% CI, 1.41-6.50; reference: male), being never married (aOR = 2.81; 95% CI, 1.17-6.76; reference: being married/a member of an unmarried couple) were associated with higher likelihood to have a checkup. CCS without healthcare coverage (aOR = 0.33; 95% CI, 0.14-0.75) and CCS being current smokers (aOR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.23-0.94) were less likely to have a checkup (Table 3).

| Checkup with a doctor | Checkup with a doctor | Healthcare cost barrier | Healthcare cost barrier | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age groups N (%) | ||||||||

| 25-29 | 1.63 (0.64-4.16) | 0.619 | 1.30 (0.42-4.06) | 0.623 | 2.75 (1.04-7.27) | 4.79 (1.39-16.54) | 0.043* | |

| 30-34 | 0.86 (0.37-2.03) | 0.74 (0.25-2.17) | 1.09 (0.40-2.96) | 0.094 | 1.53 (0.43-5.42) | |||

| 35-39 | 0.92 (0.38-2.25) | 0.98 (0.32-3.01) | 1.23 (0.44-3.43) | 2.04 (0.55-7.60) | ||||

| 40-44 | 1.05 (0.39-2.79) | 0.96 (0.28-3.28) | 0.57 (0.16-2.06) | 0.77 (0.16-3.84) | ||||

| 45-49 | 1.66 (0.64-4.35) | 1.98 (0.57-6.86) | 0.86 (0.28-2.60) | 0.98 (0.24-4.07) | ||||

| 18-24 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Sex, N (%) | ||||||||

| Female | 1.95 (1.06-3.57) | 0.031* | 3.03 (1.41-6.50) | 0.004** | 1.39 (0.68-2.85) | 0.371 | 1.05 (0.42-2.61) | 0.923 |

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Education Level, N (%) | ||||||||

| aBelow college level | 1.06 (0.60-1.87) | 0.853 | 2.00 (1.08-3.69) | 0.027* | 0.88 (0.38-2.02) | 0.758 | ||

| Some college or technical school/College graduate | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Marital, N (%) | ||||||||

| Never married | 1.89 (1.00-3.57) | 0.071 | 2.81 (1.17-6.76) | 0.025* | 1.79 (0.90-3.55) | 0.157 | 1.75 (0.69-4.43) | 0.504 |

| Divorced/ widowed/ separated | 1.90 (0.91-3.99) | 2.45 (0.96-6.24) | 1.85 (0.85-4.02) | 1.18 (0.44-3.16) | ||||

| Married/A member of an unmarried couple | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Do you have any healthcare coverage? N (%) | ||||||||

| No | 0.31 (0.16 - 0.62) | <0.001*** | 0.33 (0.14-0.75) | 0.008** | 6.08 (2.97-12.43) | <0.001*** | 8.28 (3.45-19.88) | <0.001*** |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Income level, N (%) | ||||||||

| < $15,000 | 1.51 (0.64-3.54) | 0.502 | 3.45 (1.35-8.83) | 0.007** |

||||

| $15,000 < $25,000 | 0.57 (0.26-1.25) | 3.32 (1.30-8.48) | ||||||

| $25,000 < $35,000 | 0.82 (0.28-2.35) | 4.39 (1.38-13.96) | ||||||

| $35,000 < $50,000 | 0.80 (0.35-1.85) | 4.49 (1.71-11.75) | ||||||

| Don't know/Not sure/Missing | 0.91 (0.34-2.43) | 0.69 (0.14-3.41) | ||||||

| $50,000 or more | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Health risk behaviors | ||||||||

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||||||

| bCurrent smokers | 0.62 (0.32-1.18) | 0.177 | 0.46 (0.23-0.94) | 0.033* | 1.95 (1.05-3.63) | 0.036* | 1.30 (0.58-2.92) | 0.532 |

| Nonsmokers | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Self-examined health status, N (%) | ||||||||

| Fair or poor health | 1.37 (0.73-2.59) | 0.331 | 2.59 (1.36-4.93) | 0.004** | 1.48 (0.66-3.28) | 0.341 | ||

| Good or better health | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

| Days with poor mental health, N (%) | ||||||||

| 1-13 days mental health not good | 0.93 (0.50-1.73) | 0.772 | 2.40 (1.13-5.11) | 0.008** | ||||

| 14+ days mental health not good | 1.20 (0.61-2.36) | 3.26 (1.51-7.06) | ||||||

| Zero day mental health not good | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Days with poor physical health, N (%) | ||||||||

| 1-13 days when physical health not good | 0.90 (0.49-1.68) | 0.721 | 1.93 (0.94-3.96) | 0.030* | ||||

| 14+ when physical health not good | 1.23 (0.61-2.46) | 2.65 (1.25-5.60) | ||||||

| Zero day when physical health not good | Reference | – | Reference | |||||

| Chronic conditions | ||||||||

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||||||

| > 1 | 1.09 (0.63-1.87) | 0.764 | 2.65 (1.44-4.90) | |||||

| None or 1 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Length of follow-up | ||||||||

| 26 years or more | 0.90 (0.52-1.55) | 0.707 | – | 0.44 (0.24-0.80) | 0.007** | 2.36 (1.08-5.18) | 0.032* | |

| ≤25 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||

- Models were adjusted for year of data, region, race/ethnicity, employment, number of children in household, binge drinking, physical activity, and body mass index.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

- a Below college level includes those who never attended school, those who attended only kindergarten, those who attended only elementary school and some high school, and those who were high school graduates.

- b Current smokers include those who smoked every day and those who smoked some days.

3.3.2 Experiencing healthcare cost barriers

On univariate analyses, an educational attainment below college level, being a current smoker, having > 1 chronic condition, and longer length of follow-up were associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing healthcare cost barriers among CCS. In the multivariable analysis, CCS without healthcare coverage were eight times more likely (aOR = 8.28; 95% CI, 3.45-19.88). Those with > 1 chronic health condition were twice likely to experience healthcare cost barriers compared with those with ≤1 chronic health condition (aOR = 2.36; 95% CI, 1.08-5.18). Compared with the youngest group (18-24 years), CCS of most age groups had similar experience with healthcare cost barriers; however, those ages 25-29 years were five times more likely to experience healthcare cost barriers (aOR = 4.79; 95% CI, 1.39-16.54; Table 3).

3.3.3 Receiving influenza vaccine

Female CCS were twice likely (aOR = 2.27; 95% CI, 1.03-5.03; reference: male CCS) to receive influenza vaccine. CCS with > 1 chronic health condition (aOR = 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.87; reference: CCS with none or one chronic health condition) were less likely to receive influenza vaccine. Smoking was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving influenza in univariate analysis (OR = 0.40; 95% CI, 0.21−0.77) but was not statistically significant in the multivariable model (Table 4).

| Influenza vaccine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Year, N (%) | ||||

| 2016 | 0.86 (0.44-1.67) | 0.805 | – | – |

| 2017 | 0.85 (0.41-1.74) | |||

| 2018 | 0.37 (0.07-1.80) | |||

| 2019 | 0.82 (0.26-2.63) | |||

| 2014 | Reference | |||

| Age groups N (%) | ||||

| 25-29 | 0.63 (0.25-1.58) | 0.413 | 0.36 (0.11-1.13) | 0.114 |

| 30-34 | 0.43 (0.17-1.08) | 0.22 (0.07-0.68) | ||

| 35-39 | 0.71 (0.28-1.76) | 0.37 (0.11-1.22) | ||

| 40-44 | 1.00 (0.38-2.62) | 0.60 (0.18-2.02) | ||

| 45-49 | 1.01 (0.41-2.50) | 0.63 (0.19-2.05) | ||

| 18-24 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Sex, N (%) | ||||

| Female | 1.12 (0.60-2.10) | 0.729 | 2.27 (1.03-5.03) | 0.043* |

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Region, N (%) | ||||

| Midwest | 0.96 (0.22-4.15) | 0.718 | – | – |

| South | 0.75 (0.15-3.84) | |||

| West | 0.58 (0.11-3.10) | |||

| Northeast | Reference | |||

| Education level, N (%) | ||||

| aBelow college level | 0.42 (0.23-0.79) | 0.007** | 0.75 (0.35-1.62) | 0.457 |

| Some college or technical school/College graduate | Reference | Reference | ||

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.62 (0.16-2.84) | 0.254 | 0.63 (0.12-3.27) | 0.576 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.30 (0.07-1.40) | 0.32 (0.06-1.82) | ||

| bOthers, non-Hispanic | 0.48 (0.15-1.50) | 0.72 (0.20-2.62) | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | Reference | Reference | ||

| Employment, N (%) | ||||

| cOut of work/a homemaker | 0.36 (0.14-0.93) | 0.187 | 0.42 (0.15-1.22) | 0.073 |

| A student/retired | 1.01 (0.41-2.48) | 1.73 (0.57-5.19) | ||

| Unable to work | 1.09 (0.48-2.50) | 2.33 (0.85-6.44) | ||

| Employed/self-employed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Marital, N (%) | ||||

| Never married | 0.53 (0.28-1.00) | 0.066 | 0.49 (0.20-1.19) | 0.156 |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 0.51 (0.34-1.08) | 0.53 (0.22-1.31) | ||

| Married/A member of an unmarried couple | Reference | Reference | ||

| Average number of children in household | ||||

| One child | 0.54 (0.26-1.13) | 0.210 | – | – |

| Two or more children | 0.67 (0.36-1.23) | |||

| No children | Reference | |||

| Do you have any healthcare coverage? N (%) | 0.130 | |||

| No | 0.32 (0.13-0.75) | 0.009** | 0.47 (0.18-1.25) | |

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| Income level, N (%) | ||||

| < $15,000 | 0.46 (0.20-1.06) | 0.392 | – | – |

| $15,000 < $25,000 | 0.57 (0.25-1.28) | |||

| $25,000 < $35,000 | 0.51 (0.17-1.57) | |||

| $35,000 < $50,000 | 0.92 (0.35-2.39) | |||

| Don't know/not sure/missing | 0.92 (0.35-2.39) | |||

| $50,000 or more | Reference | |||

| Health risk behaviors | ||||

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||

| dCurrent smokers | 0.40 (0.21-0.77) | 0.006** | 0.50 (0.23-1.08) | 0.079 |

| Nonsmokers | Reference | Reference | ||

| Do you binge drink? N (%) | – | |||

| Yes | 0.79 (0.39-1.58) | 0.504 | ||

| No | Reference | |||

| Active physical activity level, N (%) | ||||

| Not active | 1.50 (0.79-2.85) | 0.218 | – | |

| Active | Reference | |||

| Self-examined mental health status, N (%) | ||||

| Fair or poor health | 0.72 (0.38-1.38) | 0.326 | – | |

| Good or better health | Reference | |||

| Days with poor mental health, N (%) | ||||

| 1-13 days mental health not good | 0.86 (0.45-1.62) | 0.839 | – | |

| 14+ days mental health not good | 0.84 (0.43-1.65) | |||

| Zero day mental health not good | Reference | |||

| Days with poor physical health, N (%) | ||||

| 1-13 days when physical health not good | 0.70 (0.37-1.33) | 0.492 | – | |

| 14+ when physical health not good | 0.75 (0.38-1.51) | |||

| Zero day when physical health not good | Reference | |||

| Chronic conditions | ||||

| Body mass index, N (%) | ||||

| Overweight/obesity | 1.37 (0.77-2.42) | 0.555 | – | |

| unknown | 1.38 (0.31-6.18) | |||

| Under/normal weight | Reference | |||

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||

| >1 | 0.52 (0.29-0.91) | 0.021* | 0.43 (0.21-0.87) | 0.020* |

| None or 1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Length of follow-up | ||||

| 26 years or more | 1.56 (0.89-2.72) | 0.117 | – | – |

| ≤ 25 years | Reference | |||

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- a Below college level includes those who never attended school or attended only kindergarten, only elementary school or only some high school, and those who were high school graduates.

- b Others, non-Hispanic includes Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Multiracial, and Others.

- c Out of work group includes those who were out of work for one year or more and those who were out of work for less than one year.

- d Current smokers include those who smoked every day and those who smoked some days.

3.3.4 Impact of Medicaid expansion

CCS residing in the states with Medicaid expansion had similar outcomes compared with those residing in the states without, indicating no relation between the Medicaid expansion and the healthcare utilization and cost barrier outcomes (Supporting Information).

4 DISCUSSION

Compared with controls, CCS had lower income, lower educational attainment, more chronic health conditions, and less healthcare coverage. Also, CCS had higher proportions of being current smokers, reporting worse mental health and worse physical health. CCS had similar proportions of having a checkup and receiving influenza vaccine but a higher proportion of experiencing healthcare cost barriers than controls. Among all samples, those with multiple chronic conditions were more likely to face cost barriers. With a higher proportion of having multiple chronic conditions (98.4% vs 94.4%), CCS had a higher chance to face cost barriers in comparison with controls. Among CCS alone, being 25-29 years, no healthcare coverage, and having multiple chronic health conditions were associated with higher likelihood of experiencing healthcare cost barriers. CCS who were current smokers were less likely to have a checkup compared with nonsmoker counterparts.

Our childhood cancer survivor samples shared similarities with and differed from samples in previous studies. Most of our CCS were White, similar to the current literature.20, 21 However, most of our survivors were female (70%) compared with 54.5% in Kirchhoff et al. study.22 Our study had more uninsured survivors (18.2%) than previous studies (9.3%-10.2%).23, 24 Our findings on CCS having worse socioeconomic outcomes and worse mental and physical health confirmed previous findings.25 The proportion of current smokers among our survivors was 30.3%—higher than previous findings (i.e., 22% prevalence of CCS being smokers in a meta-analysis26 and a current smoking rate of 19% in a study using the CCSS data).27 Of note, the survivors in our sample reported a later age of childhood cancer diagnosis compared with previous studies using the CCSS data.3, 28, 29

U.S. cancer patients face serious healthcare cost barriers.30 Compared with their noncancer siblings, CCS pay more out-of-pocket medical costs.24 We found that CCS had a higher likelihood to experience healthcare cost barriers and had a higher prevalence of being uninsured compared with the general population counterparts. Our finding that a quarter of CCS reported healthcare cost barriers corroborates Beadke et al. (24.8% forgoing needed medical care due to finances).8 In our study, the proportions of having a checkup (63.6%) and an influenza vaccine (34.6%) among CCS agreed with previous studies.6, 15 Our finding that the proportions having a checkup and an influenza vaccination were similar for survivors and controls indicates equal access to primary care between the two groups. However, CCS had almost doubled the proportion experiencing healthcare cost barriers compared with controls even after adjustments with a multivariable model. This indicates unmet need by CCS for intensive long-term follow-up services beyond primary care (i.e., appointments with cancer specialists and preventive care services starting at earlier ages).2

We found that an absence of healthcare coverage was an important factor associated with healthcare cost barriers among CCS. U.S. adult survivors of childhood cancer encounter fragmented and suboptimal healthcare due to multiple issues related to health insurance hardship (e.g., change in employer-sponsored plans, substantial deductibles, and high healthcare costs).31 Addressing healthcare coverage is key to improving long-term follow-up care and, ultimately, health outcomes among CCS. Special programs that guarantee basic needs of healthcare to CCS will be helpful. Our findings showed no impact of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act on the healthcare utilization of CCS, which could be explained by a relatively small sample size. Medicaid expansion could be among the most potential programs that provide fundamental healthcare coverage (i.e., checkups with specialists) for CCS.6, 32 We suggest states with existing and future Medicaid expansion consider higher emphasis on including specific programs supporting CCS.

We found an increased likelihood of experiencing healthcare cost barriers among CCS aged 24-29 years in comparison with the youngest group (18-24 years). Meanwhile CCS of other age groups had a similar experience of healthcare cost barriers when compared with the youngest group. This finding may indicate an interrupted healthcare access when adult survivors of childhood cancer transition out from parents’ healthcare plans.33, 34 This finding also corroborates the fact that U.S. population aged 18-29 years have the highest proportion of noninsurance compared with all other age groups (30-64 years).35 Thus, we advocate for programs effectively addressing interrupted care across transitions for CCS aged 24-29 years36-38 based on the insurance disadvantage. This recommendation has contributed to the current literature that has suggested pretransition and transition planning based on CCS’ clinical needs and efficacy/comfort of specialty and primary care physicians in managing chronic health conditions connected to childhood cancer.39-41

The status of being current smokers was more prevalent among CCS than controls. Also, among CCS, being current smokers was associated with lower utilization of checkups with doctors. Meanwhile, CCS are at elevated risk for developing subsequent illnesses including cardiovascular diseases, second cancer, and pulmonary complications.42 A major cause for all these three illnesses,43 smoking itself is harmful to the health of survivors and can exacerbate late effects from the treatment for primary cancer.44, 45 Our findings show that the status of being a current smoker creates another layer of harm to survivors by decreasing healthcare utilization in addition to, previously well-known, smoking's health-worsening harm. We suggest the importance of developing tailored smoking cessation interventions for CCS.

Our study has several limitations. Although BRFSS survey data aim to represent the nation, a large portion of our childhood cancer survivor sample was from the Midwest. We lack important cancer-related information (e.g., stage of the primary cancer, type and site of cancer, type of received treatments). Additionally, our study is subject to several other limitations inherent to the BRFSS survey design, as reported by a previous study.25 These limitations include the inability to study households without phone lines, the response rate possibly affecting the representativeness (also known as nonresponse bias), and a small sample size of the survivors.

Our study's strengths include CCS and their matched noncancer counterparts, which enabled us to evaluate the impact of being a childhood cancer survivor and other factors on healthcare utilization and cost barriers. The BRFSS survey's recruitment method is not focused on hospital-based populations, offering a less biased sample (hospitals tend to recruit patients with severe health issues). Our findings help further knowledge on childhood cancer survivorship research by inclusion of unstudied predictors—marital status, employment, health-related risk behaviors, which could be associated with healthcare utilization and cost barrier in CCS—a population with continuously improved life expectancy. We used sample aged < 50 years because chronic health conditions are more prevalent in older age groups and increased use of healthcare services is also more commonly seen in aging populations as seen in a previous study.25 This age cutoff helped strengthen the opportunity to contrast healthcare utilization and cost barriers by the status of being CCS. Furthermore, our analysis included the assessment of health risk behaviors, clinical factors as need factors, and several predisposing factors that have never been studied in healthcare utilization among U.S. CCS. These focused sample and comprehensive sets of variables enhanced the ability of our study to make recommendations for long-term follow-up care for CCS.

In conclusion, CCS are more likely to encounter healthcare cost barriers compared with their general population counterparts. Among CCS, being 25−29 years, uninsured, or a current smoker is associated with poorer outcomes in healthcare utilization and access. We advocate for effective public health programs addressing care transitions and smoking cessation for this vulnerable group.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design (Nghiem, Alanaeme, Wong); data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation (Nghiem, Alanaeme, Wong, Mennemeyer); drafting (Nghiem, Wong, Alanaeme, Mennemeyer); final approval of the version to be published (Nghiem, Wong, Alanaeme, Mennemeyer)

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data used in this study are publicly available (https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html).