‘Like ships in the night’: A qualitative investigation of the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ emotional and sexual intimacy

Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer is highly distressing for families and can place strain on parents’ relationships. Parental functioning and cohesiveness are important predictors of family functioning and adaptation to stress. This qualitative study investigated the perceived impact of childhood cancer on parents’ relationship with their partner, with a focus on emotional and sexual intimacy.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 48 parents (42 mothers, six fathers) of children under the age of 18 who had completed curative cancer treatment. We analysed the interviews using thematic analysis.

Results

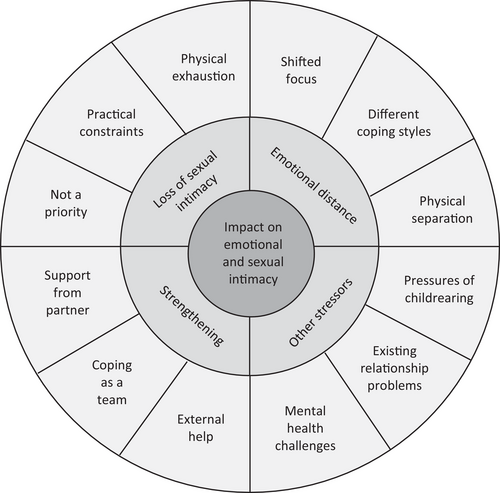

At interview, parents were on average 40.7 years old (SD = 5.5, range: 29–55 years), and had a child who had completed cancer treatment between 3 months and 10.8 years previously (M = 22.1 months). All participants were living with their partner in a married/de facto relationship. Most parents reported that their child's cancer treatment had a negative impact on emotional and sexual intimacy with their partner, with some impacts extending to the post-treatment period. Reasons for compromised intimacy included exhaustion and physical constraints, having a shifted focus, and discord arising from different coping styles. Some parents reported that their relationship strengthened. Parents also discussed the impact of additional stressors unrelated to the child's cancer experience.

Conclusions

Parents reported that childhood cancer had a negative impact on aspects of emotional and sexual intimacy, although relationship strengthening was also evident. It is important to identify and offer support to couples who experience ongoing relationship stress, which may have adverse effects on family functioning and psychological wellbeing into survivorship.

Abbreviation

-

- PAIS

-

- Psychological Adjustment to Illness Scale

1 INTRODUCTION

A child's cancer diagnosis and treatment profoundly impact parents, both individually and as a couple. After a child's diagnosis, parents are challenged by abrupt changes to daily routines and increased tension between work and family responsibilities, all while grappling with the difficult process of treatment and fear of losing their child.1-6 Parents experience an understandable shift in focus towards supporting their child during intensive cancer treatments often taking on responsibility for life-and-death decisions.1-5, 7 These challenges impact parents’ functioning as individuals and as a partnership.4, 8-14 While multiple studies have shown that separation and divorce do not appear to be more common among parents of a child with cancer than those without,15-17 parents of children with cancer have reported negative changes to their spousal relationship, including the quality of communication within the partnership,18, 19 higher marital dissatisfaction1, 20 and reduced sexual intimacy.1, 7, 21, 22

Understanding the impact of childhood cancer on the parental relationship is important given the central role this relationship plays in family functioning and cohesiveness.3 Social-ecological frameworks of disease specify how parental and wider family functioning may in some cases be impacted by, and impact, a child's cancer course.23-25 A positive family environment characterised by higher cohesion, and lower conflict, has been associated with better adjustment in children to a childhood cancer diagnosis.26-28 Conversely, marital dysfunction has been found to adversely affect the psychological wellbeing of parents,29, 30 with the potential to directly and indirectly impact children.3

Intimacy is central to positive partner relationships. It encompasses emotional, social, sexual and intellectual components,31 is positively correlated with marital satisfaction32-34 and has been found to act as an effective buffer against stress.29, 35, 36 Satisfaction with sexual intimacy has also been found to increase perceived relationship quality and in turn reduce instability in spousal relationships over the longer term.37 In the context of childhood cancer, parents with higher levels of emotional attachment and affection in their spousal relationship have been found to have more positive marital adjustment in terms of coping with emotional distress.38

Quantitative and qualitative studies to date have mainly focused on exploring the impacts of childhood cancer on parents’ marital functioning by examining parents’ experiences as individuals10, 35, 39 and by assessing levels of marital satisfaction,21, 29, 36, 38, 40 and coping mechanisms.8, 29, 38, 41, 42 Few studies have investigated childhood cancer's impact on parents’ perceptions of their intimacy, especially sexual intimacy, and intimacy in the period shortly after completion of their child's cancer treatment. This study aims to bridge this gap in knowledge, thereby informing psychosocial support for parents of children affected by cancer. We used a qualitative approach to investigate parents’ perceptions of the impact that their child's cancer had on their partner relationship, focusing on emotional and sexual intimacy.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants and recruitment

We recruited participants between 2012 and 2017 as part of ‘Cascade’ (Cope, Adapt, Survive: life after CAncEr), a randomised controlled trial of an online group-based intervention to support parents of paediatric cancer survivors.43, 44 Both parents were eligible to participate in Cascade if their child had successfully completed cancer treatment with curative intent in the last 10 years and was under the age of 18. We chose a cut-off of 10 years post treatment to capture parents’ experiences following their child's treatment completion, including impacts that may have continued in subsequent years. Eligible mothers and fathers were proficient in English and able to provide informed consent. Parents with severe mental health risks (e.g., suicidality, psychosis) were not eligible to participate and were provided with recommendations of suitable individualised supports.43, 44

We recruited parents from seven paediatric hospitals across Australia via mailed invitation packages after a suitability screening by the child's treating team. Parents opted-in to the Cascade intervention trial by returning consent forms. Ethical approval was received from institutional review boards at all study sites. Semi-structured psychosocial interviews were undertaken as part of a suite of measures administered at baseline (i.e., before participation in Cascade).43 All parents who identified as being in a cohabiting relationship with a partner at the time of the interview were invited to complete the section relating to the impact of childhood cancer on their relationship. Where both members of a couple chose to participate, they were interviewed separately.

2.2 Interview

Interview items were taken from the ‘domestic environment’ and ‘sexual relationships’ domains of the Psychological Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS; Table 1).45 The PAIS is a widely used psychosocial interview in psycho-oncology research,46, 47 including paediatric psycho-oncology.48, 49 Female research officers trained in qualitative interview methods conducted the interviews over the phone. Interviews took between 30 and 60 minutes to complete, with only sections relevant to parents’ relationship and emotional/sexual intimacy included in the current study. Other sections of the PAIS interview have been reported previously.6, 50 We also collected demographic and clinical information via a (paper or online) questionnaire administered to parents at baseline, including assessment of parent emotional distress across multiple domains (distress, anxiety, depression, anger and need for help) using the Emotion Thermometers tool.51 In line with recommendations and previous research,44 we characterised parents with a score ≥7 on any domain as experiencing clinically significant concerns, which then triggered the distress management protocol for the Cascade randomised controlled trial.43, 44

|

2.3 Analysis

We audio-recorded the interviews and then transcribed them verbatim. We reviewed sections of the interview transcripts relating to the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ relationship and then uploaded them to qualitative research software NVivo, version 11 (QSR International). We used inductive thematic analysis.52 Two researchers (Wan Ka Chow and Brittany C. McGill) read through the transcribed interviews, developed a preliminary coding tree and then coded transcripts line-by-line. As coding progressed, Wan Ka Chow and Brittany C. McGill met weekly to review the emerging themes and resolve any disagreements in the interpretation of the data. We then extracted illustrative quotes and used them to re-confirm our overarching themes and subthemes. To further enhance the credibility of analysis, we discussed emerging themes with the wider study team. We used SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp) to conduct descriptive analyses of participants’ demographic characteristics.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

Forty-eight of the 76 parents (63.2%) who opted into the Cascade program completed the baseline interview, including the section on emotional and sexual intimacy. Forty-three of these parents went on to provide additional demographic information via a questionnaire. Forty-two mothers (87.5%) and six fathers (12.5%), mean age 40.7 years (SD = 5.5, range: 29–55 years), were included in the current study (Table 2). All participants were either married, or in a de facto relationship, and reported living with their partner. The sample included one partner dyad. The mean age of the parents’ child at the time of their cancer diagnosis was 5.2 years (SD = 4.9, range: 0.01–15 years) and the mean time since their child completed treatment was 22.1 months (SD = 24.5, range: 3–129 months; Table 3). We allowed the parent of a child who completed treatment a little over 10 years ago (i.e., 129 months) to continue in the study (which was part of the larger Cascade trial) as they identified needing psychosocial support for issues relating to their child's cancer. We excluded two eligible interviews from our qualitative analysis due to poor audio quality and a further four eligible interviews due to recording problems/incomplete recordings. Eight parents who completed the interview were excluded from the current study as they did not identify as being in a cohabiting relationship with a partner at the time of interview (including three single parents, three separated/divorced parents and two widowed parents).

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Relationship to childa | |

| Father | 6 (12.5) |

| Mother | 42 (87.5) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | |

| At the time of interview | 40.7 (5.5) |

| Range | 29–55 |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school | 6 (14.0) |

| Certificate/diploma | 10 (23.3) |

| University degree | 15 (34.9) |

| Postgraduate degree | 11 (25.6) |

| Relationship statusa | |

| Married/de facto | 48 (100) |

| Number of children | |

| 1 | 3 (7.0) |

| 2 | 21 (48.8) |

| 3 or more | 18 (41.9) |

| Mean Emotion Thermometer ratings (SD) | |

| Distress | 2.36 (2.3) |

| Anxiety | 3.83 (2.6) |

| Depression | 1.52 (1.7) |

| Anger | 2.19 (2.1) |

| Need for help | 1.86 (1.9) |

| Emotion Thermometer ratings ≥7 | |

| Distress | 2 (4.8) |

| Anxiety | 7 (16.3) |

| Depression | 0 (0) |

| Anger | 3 (7.1) |

| Need for help | 1 (2.4) |

| Any subscale ≥7 | 11 (26.2) |

- Note: All demographics, except the ones marked with ‘a’, assessed via baseline questionnaire (N = 43, with data from one participant missing).

- a Assessed via interview (N = 48).

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Child's gender | |

| Male | 27 (64.3) |

| Female | 15 (35.7) |

| Mean age in years | |

| At interview (SD) | 8.1 (4.7) |

| Range | 2–17 |

| At diagnosis (SD) | 5.2 (4.9) |

| Range | 0.01–15 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) | 7 (16.7) |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) | 1 (2.4) |

| Brain cancer | 7 (16.7) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (14.3) |

| Neuroblastoma | 6 (14.3) |

| Sarcoma | 7 (16.7) |

| Wilms’ tumour | 4 (9.5) |

| Others | 6 (14.3) |

| Treatmentb | |

| Surgery | 25 (59.5) |

| Chemotherapy | 39 (92.9) |

| Radiotherapy | 15 (35.7) |

| Transplant (bone marrow, stem cells or cord) | 6 (14.3) |

| Months since treatment completion | |

| Mean (SD) | 22.1 (24.5) |

| Range | 3–129 |

| Time since treatment completion categorised | |

| <12 months | 18 (42.9) |

| 12–60 months | 20 (47.6) |

| 61–120 months | 4 (9.5) |

- a Assessed via baseline questionnaire (N = 43, with data from one participant missing).

- b Some children had more than one type of treatment.

3.2 Impact of childhood cancer on parents’ relationship

Our analysis derived four main themes and 12 subthemes characterising the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ perceptions of emotional and sexual intimacy within their partner relationship (Figure 1 and Table 4).

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional distance | Shifted focus |

‘Umm the kids took a lot of focus, but in saying that, the kids took a lot of focus for both of us. We did grow apart ….’ (mother of an 8-year old, 28 months post treatment) ‘I don't like to talk about myself too much, I'd rather just talk about the two kids that—the two people in our lives that matter the most…’ (mother of a 10-year old, 11 months post treatment) |

| Different coping styles |

‘I was in my own little bubble, and he was trying to get in there, into that bubble, but I wasn't really interested. I just wanted to get through it on my own… Everyone copes with things differently and that's what we realised. We realised that he wanted to have more attention and wanted to talk to me and talk about things, and whereas I wanted to not talk about it and just get on with it’. (mother of a 3-year old, time post treatment unknown) ‘I think it was easy way out for him to just switch off from it all and that really hurt because the times when I needed him was when he wasn't there’. (mother of an 11-year old, time post treatment unknown) |

|

| Physical separation | ‘I think at the time of his diagnosis management, [marital relationship] strained in many ways because you don't see each other, and we tended to be passing like ships in the night. Not certainly what you call a normal relationship when you're dealing with a child with a serious illness’. (father of a 13-year old, 4 months post treatment) | |

| Loss of sexual intimacy | Physical exhaustion |

‘I mean, we were in hospital. When you're not, you're bone tired at the end of the night. You've worked through everything that needed to be done that day, you had a kid that's just been through surgery…’ (mother of a 4-year old, 17 months post treatment) ‘You're spending large quantities of your life in hospital, and when you get home and into your own bed, you just go to sleep’. (mother of a 7-year old, 12 months post treatment) |

| Practical constraints |

‘Obviously when you're at [charity accommodation] all in one room together, it's virtually impossible. And when he'd come up [to the hospital] and when we were at my mum and dad's house, obviously that's not possible. Like I said, you know to be able to find some time when they're all asleep…It's not an easy thing to do’. (mother of a 2-year old, 23 months post treatment) ‘The fact that I was spending so many nights obviously away from my wife, I think out of the eight months that [child] was in and out of hospital, I think I spent about 10 or 15 nights at home. So it doesn't allow for much time to be intimate…’ (father of a 4-year old, 9 months post treatment) |

|

| Not a priority |

‘I would say at the beginning, it kind of feels a bit odd. Slightly wrong to be doing that, when your daughter's in the room next door going through what she's going through… I spoke to other parents about that and they were the same’. (mother of a 7-year old, 12 months post treatment) ‘I remember thinking I will never be able to smile again…It took a long, long time before you could consider anything that was joyful. You know, we were in a completely different head space…’ (mother of a 5-year old, 21 months post treatment) |

|

| Strengthening of the relationship | Support from partner |

‘I think looking back we did extraordinary well through such a horrific time. He was very involved so it wasn't completely all on my shoulders’. (mother of a 6-year old, 12 months post treatment) ‘I guess looking back before this happened I was still as supportive of him. We're quite a good team, when one of us is down the other one picks up the slack and then if the other one's down the other one just picks up’. (mother of a 4-year old, 6 months post treatment) |

| Coping as a team | ‘I think it actually brought us a bit closer as a team…We kind of support each other, and we just did what we had to do. I guess you see each other in a different light and I probably saw the softer side of him and supportive side of him and the stronger side as well’. (mother of a 15-year old, 27 months post treatment) | |

| External help |

‘Fortunately, we were both strong enough to get through that and we had plenty of other people around that had concerns for our wellbeing and how we were’. (mother of a 4-year old, 17 months post treatment) ‘I think straight after [diagnosis], we just kind of coasted along while [child] was getting his treatment. Then afterwards was when it kind of hit us. So we went through a bit of a rough patch and went to counselling and things. But yeah we're fine now’. (mother of a 3-year old, time post treatment unknown) |

|

| Other life stressors | Pressures of child rearing | ‘The kids took a lot of focus for both of us. We did grow apart, but we're both also of the thinking that you know marriage is hard work anyway’. (mother of an 8-year old, 28 months post treatment) |

| Existing relationship problems | ‘I think there is not much intimacy anyway so from there I don't know whether that umm comes with the picture but I guess you know general exhaustion and things, I don't know. [Child's diagnosis] compounded the existing situation maybe….’ (mother of a 6.5-year old, 20 months post treatment) | |

| Mental health challenges |

‘We were probably having difficulties prior to the diagnosis with his mental health issues’. (mother of a 2-year old, 23 months post treatment) ‘It wasn't a good time. He was suffering quite severe depression’. (mother of an 11-year old, time post treatment unknown) |

3.3 Theme 1: Emotional distance

Many parents perceived negative changes to emotional intimacy with their partner after their child's cancer diagnosis. Parents commonly described their relationship as ‘strained’, having ‘drifted apart’, or having ‘been through a rough patch’. Parents perceived these changes especially at the beginning of their child's treatment, with some experiencing ongoing difficulties after treatment completion. We identified three subthemes that captured parents’ description of the reasons for their compromised emotional intimacy with their partner: shifted focus, different coping mechanisms, and physical separation.

3.3.1 Shifted focus

‘We have had no time for each other at all; I've been caring for my sick child 100% of the time. And so, when he comes home, I'm like “Tag!” and I'm out of here, I need a break, I need some time to myself… I think it's been really hard on our marriage, plus the worry and the stress of it all, and plus having zero time for each other’. (mother of a 4-year old, 3 months post treatment)

3.3.2 Different coping styles

‘Initially we were on a different page in terms of how we were dealing with it. I'm quite emotional. He was a bit more defensive against that and a bit more upbeat. We were just in different spaces… Despite being respectful of where each other were, I think that created a degree of discord between us’. (mother of a 2-year old, 10 months post treatment)

3.3.3 Physical separation

‘During those hundred days [of treatment], obviously the level of discussion was less because you're physically not in the same place’. (father of a 4-year old, time post treatment unknown)

3.4 Theme 2: Loss of sexual intimacy

‘There's been no sexual activity for quite some time… there were no activities to speak of for about nineteen months’. (mother of a 15-year old, 9 months post treatment)

Loss of sexual interest was a common experience for parents during their child's treatment, and into their child's early survivorship. However, very few parents described reduced sexual interest and frequency as problematic and few parents described experiencing reduced sexual satisfaction. Parents described various reasons for compromised sexual intimacy with their partners, described below.

3.4.1 Physical exhaustion

‘…you're just so exhausted you can't even begin to try and meet that other person's needs because you're not even meeting your own’. (mother of 2-year old, 10 months post treatment)

3.4.2 Practical constraints

‘….we also didn't see each other; it was either at certain points, uh, one of us was there and then it would be a swap-over, a pretty quick swap-over in the hospital, and then go’. (father of a 13-year old, 4 months post treatment)

3.4.3 Not a priority

‘It was definitely like the last thing on my mind, like I just had no care for it at all’. (mother of a 4-year old, 27 months post treatment)

‘…, the amount of stress I was under, I couldn't imagine myself ever actually experiencing pleasure of any kind’. (mother of a 2-year old, 6 months post treatment)

3.5 Theme 3: Strengthening of the relationship

Despite expressed challenges, many participants perceived a strengthening of their relationship. Some parents expressed concern that the stress of the cancer experience could lead to relationship discord or even separation, and so they made deliberate efforts to maintain their relationship. Parents’ descriptions of ways in which their relationship strengthened are reported as three subthemes: receiving support from their partner, coping as a team, and seeking external help.

3.5.1 Support from partner

‘[Husband] isn't a communicator. I am, but he's a good listener so we kind of work that way… I'll talk and he won't say a lot. But I know he's listening and then every now and then he'll say “I feel the same way” … so I always knew that he was on the same page’. (mother of a 6-year old, time post treatment unknown)

3.5.2 Coping as a team

‘When I was having a bad day, he would be having a good day. When he was having a bad day, I'd be having a good day. So we sort of, really, fed off each other… that was quite good’. (mother of a 6-year old, 74 months post treatment)

3.5.3 External help

‘I just struggled with some of the things [partner] was saying … I didn't really understand where he was coming from. But this friend that I spoke to actually made me see it from his point of view and that kind of improved our relationship’. (mother of a 4-year old, 6 months post treatment)

3.6 Theme 4: Other life stressors

Although having a child with cancer was a significant stressor, parents also identified other factors that impacted their relationship. The main stressors raised were the pressures of child rearing, existing relationship problems and mental health issues.

3.6.1 Pressures of child rearing

‘The fact that you know we've got our three children who were obviously very demanding, … a lot of our focus is on them and just getting through the days right’. (father of a 4-year old, 9 months post treatment)

3.6.2 Existing relationship problems

‘… I don't know whether we can put it down to his diagnosis. Or whether it's just a thing that happens when you're married for a long time and you're tired … but it seems like couples who don't even have [a child with cancer] have same thing’. (mother of a 3-year old, time post treatment unknown)

3.6.3 Mental health challenges

‘Before [child's] diagnosis my husband was having a really tough time with depression and anxiety as a result of work… So we were like passing ships… He's dealt with it or not dealt with the whole situation his way. I've dealt with it my way…we've had moments where I have actually thought “are we actually going to make it?”’. (mother of a 15-year old, 9 months post treatment)

4 DISCUSSION

This study sought to examine the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ relationships, with a focus on emotional and sexual intimacy. We did this through a semi-structured interview with parents in the early years following their child's cancer treatment. Many parents in the study reported a decline in both emotional and sexual intimacy with their partner, which sometimes persisted beyond their child's cancer treatment. Key contributors to these changes included parents shifting their focus to prioritise their child's wellbeing over their own and their partner's needs, as well as practical and physical constraints associated with their child's treatment. Physical exhaustion and discord arising from different coping styles also contributed. Despite reports of emotional and sexual distancing, many parents acknowledged their relationship was strengthened as a result of their child's cancer experience.

Parents’ reports of compromised emotional intimacy align with findings from previous studies. Negative changes to emotional intimacy are especially common during intense periods like diagnosis and treatment.36, 40, 53 Most previous studies suggest that intimacy issues largely resolve over the long-term,36, 53 yet our results indicated that for some parents they continued through the early years after treatment. Physical separation due to hospital stays and in some cases geographical distance made it difficult for couples to maintain effective communication and share the psychological burden of caring for their child, both of which have been associated with low levels of marital satisfaction in a child's early survivorship.9 These challenges are likely exacerbated by the ‘tyranny of distance’ in Australia, with families from rural and remote locations typically having to travel long distances to access tertiary care. Challenges associated with physical separation are likely to have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, with increased logistical complexity around caregivers accessing and visiting hospitals, and the movement of individuals between households. Previous research indicates that perceived difficulty meeting a partners’ emotional needs, lack of emotional closeness and negative perception of closeness are associated with long-term relationship strain.8, 36, 53, 54 Our findings highlight the value of providing support for families, which reduces the need for physical separation and facilitates parents sharing the demands of caring for their child during treatment (e.g., treating children closer to home, providing families with access to accommodation close to treatment centres, which allows more than one parent to stay).

Our results concerning the decreased frequency of parents’ sexual intimacy builds on the small number of studies in this area.1, 7, 20 Parents in the current study generally did not perceive this change as problematic. This is congruent with previous research that suggests that emotional intimacy may be more valued by parents, and is a better predictor of relationship satisfaction than sexual intimacy.33, 55 Although decreased sexual intimacy during times of stress is commonly reported by parents, studies to date have not provided an in-depth understanding of the underlying causes in the context of childhood cancer. Parents in our study expressed that they found sexual intimacy incongruent with their child's pain and suffering and described a reluctance to prioritise themselves and their own needs. From parents’ reports, we found no evidence of functional sexual difficulties, or reduced sexual pleasure, highlighting the impact of the stressors associated with childhood cancer on psychological rather than biological aspects of parents’ sexual relationship. Our findings may be useful to normalise changes to sexual intimacy for parents of children affected by childhood cancer.

Crucially, not all parents experienced negative impacts on their relationship with their partner. Some parents demonstrated resilience through coping together as a couple, sharing responsibilities and seeking external support. Consistent with previous studies, parents in our study described benefiting from practical support and encouragement from their partner,4, 56, 57 with several parents reporting that the experience of childhood cancer strengthened their relationship. The positive relationship outcomes expressed by some parents in our study align with research suggesting the experience of childhood cancer can lead to positive adjustment and psychological growth in some family members.58, 59 Nevertheless, our finding that many parents were experiencing additional life stressors outside their child's cancer experience, including significant mental health challenges, speaks to the importance of thorough psychosocial assessment by healthcare professionals. Such assessment should incorporate broader stressors impacting on parents’ lives, including the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as identifying and considering current supports available to them.

This study is one of few to explore the impact of childhood cancer on parents’ emotional and sexual intimacy. Using PAIS, a well-validated semi-structured interview tool,46, 47 our findings provide an important ‘snapshot’ of parents’ functioning in their child's early survivorship. While most participants in our study were parents of children who completed cancer treatment in the last 5 years, some completed treatment as long as 10 years ago. This heterogeneity may have impacted our findings in a number of ways as the challenges parents experience can both ease with time60, 61 or become established and/or worsen.10, 62 Although generalisability is not typically the aim of qualitative research, we acknowledge that this study does not capture all parents’ experiences. Parents who self-selected to participate in Cascade may have differed in terms of their functioning and/or psychological distress from other parents of childhood cancer survivors. Indeed, parents’ ratings on the Emotion Thermometers Tool at baseline indicates that our sample was not highly distressed. As is common in paediatric research, we experienced difficulties recruiting fathers, likely resulting in a less nuanced understanding of fathers’ perspectives.4, 63-65 The relative over-representation of mothers may have influenced our findings, as mothers may express more psychological and/or marital distress than fathers,2 as well as having different perspectives on intimacy.66

Further, our sample only included one parent dyad, and our narrow definition of the family environment, with a focus on cohabiting partners, precluded us from exploring the perspectives of divorced and separated couples, nor parents who were widowed or single and may have had a partner living separately. We acknowledge that families can be diverse in structure, and that parents who did not fit our study inclusion criteria may also experience disruption to their emotional and sexual intimacy in the context of their child's cancer diagnosis. Finally, the requirement that parents be able to speak English in order to participate also limited the involvement of parents from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Future research should include perspectives from culturally and linguistically diverse as well as more structurally diverse families, parents living separately from their partner, and parents who have separated/divorced. Future research should also focus on recruiting more parent dyads, address the challenge of recruiting fathers, and explore the issue of relationship strengthening directly.

5 CONCLUSION

While many parents described negative impacts on the emotional and sexual intimacy resulting from their child's cancer experience, some also perceived a strengthening of their relationship. We identified several factors that contributed to decreased emotional and sexual intimacy, knowledge that may be valuable for healthcare professionals providing support for couples navigating their child's cancer experience. Our findings suggest that it may be useful to support parents to successfully navigate situations in which each of them react and cope differently, as well as encouraging couples to invest in strengthening their relationship as being protective for the whole family unit as well as contributing towards self-care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the parents who participated in this study. We would like to acknowledge the following people who have supported Cascade: Antoinette Anazodo, Julia Bäenziger, Belinda Barton, Lauren Carlson, Lauren Kelada, Mark Donoghoe, Richard De Abreu Lourenco, Luciano Dalla-Pozza, Emma Doolan, Peter Downie, Gadiel Dumlao, Holly Evans, Afaf Girgis, Martha Grootenhuis, Janelle Jones, Madeleine King, Stephanie Konigs, Maggie Leung, Cherie Lowe, Kate Marshall, Sanaa Mathur, Maria McCarthy, Michael Osborn, Pandora Patterson, Eden Robertson, Nicole Schneider, Akshay Sharma, Cathryn Restifo, Kate Turpin, Janine Vetsch and Helen Wilson. The Cascade project was funded by Cancer Australia (APP1065428) as well as a Cancer Council New South Wales Program Grant (PG16-02) with the support of the Estate of the Late Harry McPaul. The Cascade trial was endorsed by the Australian and New Zealand Children's Haematology/Oncology Group. Claire E. Wakefield is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1143767 and APP2008300). Ursula M. Sansom-Daly is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1111800) and an Early Career Fellowship from the Cancer Institute of New South Wales (ID: 14/ECF/1-11, followed by 2020/ECF1163). The Behavioural Sciences Unit is proudly supported by the Kids with Cancer Foundation.

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

[Correction added on November 25, 2022 after first online publication: CRUI-CARE funding statement has been added.]

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors hereby declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.