Point-of-care testing allows successful simultaneous screening of sickle cell disease, HIV, and tuberculosis for households in rural Guinea-Bissau, West Africa

Federica Menzato and Luca Bosa contributed equally to this work.

This manuscript was presented as a poster at the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Meeting December 2018: Menzato F et al. Successful simultaneous screening of sickle cell disease, HIV and tuberculosis in rural Guinea-Bissau, West Africa through rapid tests and a standardized clinical questionnaire: An outreach program due to a public–private partnership. https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/132/Supplement%201/4715/262460/Successful-Simultaneous-Screening-of-Sickle-Cell

Abstract

Diagnosis of noncommunicable genetic diseases like sickle cell disease (SCD) and communicable diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or tuberculosis (TB) is often difficult in rural areas of Africa due to the lack of infrastructures, trained staff, or capacity to involve families living in remote areas. The availability of point-of-care (POC) tests for the above diseases offers the opportunity to build joint programs to tackle all conditions. We report successful simultaneous screening of SCD, HIV, and TB utilizing POC tests in 898 subjects in Fanhe, in rural Guinea-Bissau. Adherence was 100% and all diagnosed subjects were enrolled in care programs.

Abbreviations

-

- AHEAD

-

- Aid Health and Development Onlus

-

- Hb

-

- hemoglobin

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- HRF

-

- Hospital Raoul Follereau

-

- NGO

-

- non-governmental organization

-

- POC

-

- point of care

-

- SCD

-

- sickle cell disease

-

- TB

-

- tuberculosis

1 INTRODUCTION

Several “big killers” have been identified in Africa, some of which are infectious diseases that are widespread in African countries, like malaria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, or tuberculosis (TB), while others are genetic disorders like sickle cell disease (SCD). All present a high morbidity and mortality toll1, 2 and challenges for the fragmented and overburdened African health systems. Access to health services for rural populations is further limited and, in some villages, basic health care and routine screening are seldom available due to limited diagnostic capacity, lack of specialized staff or other resources.3 Therefore, people are not diagnosed or are diagnosed late for SCD, HIV, TB, resulting in high morbidity and mortality. Recently, rapid tests for both HIV and SCD have become available in the market and one for TB is currently under development,4, 5 offering the opportunity to plan screening programs at the point of care (POC) in rural areas, reaching underserved populations. Tackling diseases with different etiologies (SCD is a genetic noncommunicable disease, while HIV and TB are infectious communicable diseases with different mechanisms of spread) should include joint and coordinated actions among specific disease programs, which, unfortunately, often proceed separately. Nevertheless, a trend in this direction has recently become more evident, with joint efforts to combine HIV, TB, and SCD programs in order to benefit from joint support of infrastructures and networking of sample collection.6, 7 Simultaneous screening of three big diseases at the POC in rural areas would save time and resources, while identifying people in need of further specialized diagnostic or follow-up.

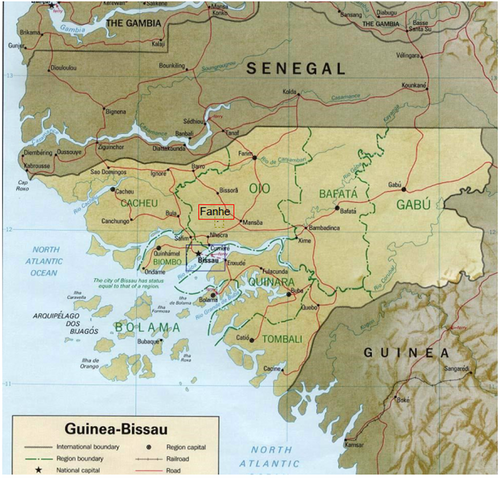

Guinea-Bissau is a West African country with a high TB/HIV burden.8 Both HIV1 and HIV2 are present, with an overall HIV incidence per 1000 people (all ages) of 1.15 (95% CI: 0.92–1.41), although data collection has been hampered by chronic political instability and has been limited to the urban areas of Bissau, Gabu, and Bafatà.9, 10 TB is widespread in the country with official data reporting TB rate at 361 (234–516)/100,000 population.8 There are National HIV and TB programs, but underdiagnosis and underreporting are common for both diseases due to limited infrastructure and limited screening in rural areas, often resulting in lack of access to health care or underdiagnosis when patients do access health centers.8, 10, 11 There is no National SCD screening program, and routine tests for SCD are not available, hence prevalence data are limited and come from pilot projects.12 Several POC kits in Guinea-Bissau are available and currently used for routine diagnosis of HIV1 and HIV2 (determine HIV1/HIV2, Genie III HIV-1/HIV-2, Immunoflow HIV1-2, SD Bioline HIV-1/2 3.0),13 but not yet for TB and SCD screening.

In spite of the limited resources dedicated to the public health system, collaboration with the private sector, charities, and international institutions has allowed support of public health facilities with specific interventions, involving the National Reference Center for Tuberculosis Hospital Raoul Follereau (HRF), the Aid Health and Development Onlus (AHEAD), and the University of Padova.14-16 Building on this previously established network, we therefore designed a short-term intervention in the rural village of Fanhè (Figure 1) where the Italian non-governmental organization (NGO) “Friends of Guinea-Bissau” supports a local school and provides a nurse a couple of days per week. The primary objective was to evaluate the feasibility of utilizing simultaneously POC tests for SCD, HIV, and a questionnaire to screen for TB in a rural area of Guinea-Bissau during a health visit; secondly, we aimed to identify patients with SCD or HIV and enroll them in appropriate follow-up programs, as well as to identify suspected cases of TB eligible for indepth diagnostic screening; lastly, we wanted to determine hemoglobin (Hb)S prevalence in order to plan future interventions, as epidemiological information is available only for the capital city of Bissau.12

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The small rural village of Fanhe is in the countryside North-East of the capital city of Bissau. The village has a local school and a basic dispensary with a nurse a few days a week. A small regional hospital is present in Mansoa and a rural health center is in Nhacra, both at 25 km from Fanhe. The pilot screening intervention was designed in 2018 in three phases: preparatory phase (February–March), temporary outreach health post for screening (March), and follow-up for enrollment in dedicated programs (April–May).

2.1 Preparatory phase

In preparation of the health post opening, the chiefs of the rural community villages and the local nurse informed the households through two collective meetings and home visits regarding the three objectives of the pilot project and its modalities after accepting the proposal made by the NGOs and the HRF staff (February–March 2018). The meetings were held in Portuguese-Creole and in one of the local languages, Balanta. The local chiefs organized the schedule of the health visits according to each household's availability.

2.2 Temporary outreach health post for screening

In the second phase a temporary health post was organized for 10 days: three nurses and two physicians from the HRF in Bissau, linguistically competent for Portuguese-Creole and local dialects, administered the standardized questionnaire (Supporting Material S1) and the physical examination, while two pediatric residents from Italy aided in the clinical examination. After performing the clinical visit and the TB standardized questionnaire, each patient was offered the possibility to perform the rapid tests for SCD (Sickle SCAN, BioMedomics, Inc, Morrisville, NC, USA) and HIV (Determine HIV-1/HIV-2, Alere Inc, Waltham, MA, USA). After oral informed consent collection, a previously trained local nurse supervised by two physicians of the international team collected the blood samples from a finger prick simultaneously for the SCD and the HIV tests; the procedure took less than 1 min for both and the average waiting time for the results was 20 minutes.

The results were communicated to all individuals immediately. Individuals with Sickle SCAN positive results underwent collection of a second blood sample on Guthrie card for confirmatory molecular analysis of the beta globin gene to be performed in Italy and received health education on SCD. Patients with HIV Determine positive test were informed of the results and advised to continue to the follow-up phase; patients with suspicion of TB were also advised to perform the appropriate diagnostic evaluation in the follow-up phase.

2.3 Follow-up phase

During the third phase (April–May), subjects with suspected TB and/or HIV received free transportation to the HRF for TB diagnostic evaluation according to the national protocol or HIV confirmatory test. The timing of the follow-up and the visits were organized by the local nurse.

3 RESULTS

All 898 inhabitants (32 families) living in Fanhe who were present at the time of the pilot project accepted to participate in the simultaneous screening program, underwent clinical examination, and responded to the TB questionnaire; all performed the finger prick for HIV and SCD rapid test. Overall 395 were males (44%) and 503 females (56%), with mean age of 31.3 years (range: 2 months to 88 years).

3.1 Sickle cell screening results and demographics

At Sickle SCAN, 16/898 (1.78%) were HbAS (children nine of 16); none were HbAC or HbSS. All 16 Sickle SCAN-positive HbAS samples underwent molecular analysis and the results were confirmed. All patients received information on the HbAS carrier state and health education on SCD in their local language. Demographics and characteristics of the individuals with HbAS are described in Table S1. Eight belonged to the same three families (mother and two children for two families; mother with one child); the remaining were not related.

3.2 HIV and tuberculosis screening results

At Determine HIV rapid test, 61/898 (6.79%) were HIV positive (children nine of 61). A total of 93/898 (10.35%) presented clinical suspicion of TB (children 33/93). Twelve (1.3%) had a suspicion of TB and were also HIV positive (children: 2/12). For subjects with a suspicion of TB or who were HIV positive, free transportation was arranged to the HRF for complete TB diagnostic workup and a second HIV confirmatory Rapid Test. All HIV-positive tests were confirmed and patients enrolled in clinical care in a nearby village dedicated HIV rural health clinic; 30% of patients with TB suspicion had the diagnosis confirmed by X-ray/sputum smear examination and were enrolled in appropriate care programs at the TB rural health clinic.

4 DISCUSSION

Our pilot project demonstrates the feasibility of simultaneous POC testing for genetic and communicable diseases in rural Guinea-Bissau, with good capacity of the local staff to learn how to perform the rapid tests, willingness of families to undergo testing if adequately informed, and adherence of families to follow-up programs, in case of need.4, 5 Dedicated staff training was possible in a short period of time and a brief supervision of 15 days allowed correct interpretation of POC test results in all cases but two, indicating that with long-distance supervision, results could even be improved. The rural community's acceptance of the screening project was satisfactory, with 100% households’ participation, highlighting the importance of preliminary health information and community engagement in screening programs.17

Water and sanitation conditions in the Fanhe area were poor, as well as electricity support, similarly to other parts of the country.18 Moreover, rate of illiteracy was high, with low basic health knowledge and a high proportion of adults who spoke only local languages. These factors will need to be taken into consideration in planning more stable screening programs and follow-up care requiring adherence to treatment or health behaviors in SCD such as penicillin prophylaxis or prevention of vaso-occlusive crisis and spleen sequestration or fever management.

The frequency of HbAS in families (1.78%) was overall lower than the one reported recently in an urban pediatric population in Bissau, which was 6.95% HbAS, 0.94% SS, and 0.23% AC13; however, our sample is small and future studies including larger pediatric populations from different ethnic backgrounds and areas of the country are needed to describe the epidemiology of the sickle gene in Guinea-Bissau. None of the children in this group had SCD; no stillbirths or deaths in childhood occurred in the families with the sickle trait.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This pilot study confirms the opportunity that rapid tests offer to scale-up diagnosis and treatment in Africa and the feasibility of a simultaneous population screening at the POC in rural areas of Guinea-Bissau for three “big diseases” (SCD, HIV, and TB). The simultaneous screening with rapid test and standardized clinical examination is a model that could be replicated in other rural settings of Guinea-Bissau to benefit from joint communicable and noncommunicable disease programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project was supported by AHEAD Onlus. The authors would like to thank Guido Maruelli coordinator of “Friends of Guinea-Bissau” and Mamadu Saliu Sanha Representative of AHEAD for the support in the project, as well as the local logistic staff, nurses, and technicians who contributed to improving health care for the rural population. The pediatric residents involved in the project were part of an International Outreach Program of the Pediatric Residency School of the University of Padova.

Open access funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

[Correction added on 25 November 2022, after first online publication: CRUI funding statement has been added.]

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest for the research reported in this manuscript.