Child Poverty, the Great Recession, and the Social Safety Net in the United States

Abstract

In this paper, we comprehensively examine the effects of the Great Recession on child poverty, with particular attention to the role of the social safety net in mitigating the adverse effects of shocks to earnings and income. Using a state panel data model and data for 2000 to 2014, we estimate the relationship between the business cycle and child poverty, and we examine how and to what extent the safety net is providing protection to at-risk children. We find compelling evidence that the safety net provides protection; that is, the cyclicality of after-tax-and-transfer child poverty is significantly attenuated relative to the cyclicality of private income poverty. We also find that the protective effect of the safety net is not similar across demographic groups, and that children from more disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those living with Hispanic or single heads, or particularly those living with immigrant household heads—or immigrant spouses—experience larger poverty cyclicality than those living with non-Hispanic white or married heads, or those living with native household heads with native spouses. Our findings hold across a host of choices for how to define poverty. These include measures based on absolute thresholds or more relative thresholds. They also hold for measures of resources that include not only cash and near-cash transfers net of taxes but also several measures of the value of public medical benefits.

INTRODUCTION

The Great Recession led to massive job loss and historic increases in unemployment durations. Employment in the United States fell by more than 8 million between January 2008 and December 2009 and unemployment rose to a peak of 15.6 million persons in October 2009 (both seasonally adjusted). In the meanwhile, median real household cash income also fell, from $57,357 in 2007 to $52,690 in 2011, and has turned back upward to $53,657 in 2014 (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015; figures are in real 2014 dollars).

These trends in median cash income are useful but are unlikely to tell the whole story. There is substantial evidence that the effects of economic cycles are larger for less-skilled workers (Gundersen & Ziliak, 2004; Hoynes, Miller, & Schaller, 2012); thus, the effect of the Great Recession on household incomes may be larger in relative terms for households in the lower end of the income distribution.1 Additionally, the overall trend in household income captures not only the shock to employment and earnings, but also the response of the social safety net including public assistance (e.g., Food Stamps), social insurance (e.g., Unemployment Insurance [UI]) programs and the stimulus programs of 2008 and 2009. To what extent did these policies and programs mitigate the earnings and income losses of the Great Recession?

In this paper, we empirically investigate these issues. First, we estimate the cyclicality of being below various multiples of the ratio of household income relative to poverty and how these vary as we move up the income to needs distribution. Second, we examine how the broader social safety net mitigates the income loss in economic downturns, capturing effects on a broad post-tax-and-transfer measure of household resources. We do this in an aggregate fashion, capturing the overall net effect of the safety net as well as the labor market shock on cyclicality for these measures. Third, we explore how these findings differ for married compared to single heads, by race and ethnicity, and for immigrant-headed or immigrant-spouse versus native-headed households with native spouses. Throughout our analysis, we focus on children and examine household income relative to poverty. Children are a particularly important group because they consistently have the highest poverty rates in the United States.2 A further reason to focus on children is that poverty has deleterious effects on children (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997) and they are the beneficiaries of much of the safety net.

In this analysis, we use data on child poverty by state and year for the period 2000 to 2014 and study the effect of the business cycle on children's economic well-being. By using data for 2000 to the present, we focus on the social safety net as currently structured, in the post-welfare reform world. We estimate state panel data models and measure the economic cycle with the state unemployment rate. We identify the key parameter—how changes in the business cycle affect child poverty—using variation in the timing and severity of cycles across states, controlling for state and year fixed effects. In our models, we analyze neither the causal effects of specific elements of the social safety net nor household behavioral responses to specific programs, although our reduced-form analysis does also incorporate the net behavioral responses to the current safety-net programs and any changes to these programs in our time period. Instead, we are interested in evaluating the overall effects of the social safety net writ broadly and how it varies as we move up the income-to-poverty distribution.

Given our interest in understanding the role that the social safety net plays in mitigating the adverse effects of shocks to earnings and income, in our main results we use two measures of resources to construct child poverty. The first, private income (PI) poverty, uses a resource measure for households that includes earned income, private transfers, and asset income. The second, after-tax-and-transfer (ATT) poverty, uses a resource measure equal to PI plus cash and near-cash in-kind government transfers (including social insurance) less net taxes. As we discuss below, our measure of ATT poverty shares many (though not all) features of the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), the new poverty statistic released by the Census beginning in 2011. (Note we discuss alternative ways to measure poverty and the implications of their use below.)

For these two resource measures, we construct, for each state and year, the share of children with income below 50, 100, 150, and 200 percent of the household's poverty threshold. For the poverty threshold, we use the Historical SPM thresholds developed by Fox et al. (2015a), who employ available historical data to construct poverty thresholds back to 1967 consistent with the Census Bureau's current SPM threshold. In sum, our measure of ATT poverty differs from the Census official poverty by (i) using a post-tax-and-transfer measure of income including near-cash in-kind transfers, (ii) using the Historical SPM thresholds from Fox et al. (2015a), and (iii) treating the household as the relevant unit for measuring poverty. These choices address many of the critiques of the official poverty measure made by Citro and Michael (1995) and Blank (2008).3

Using these data on income relative to poverty, we establish our main results comparing the cyclicality of PI poverty and the gradient as we move up the income-to-poverty distribution. Second, by comparing the cyclicality of PI poverty to that of our ATT poverty, we reveal the aggregate protection that is provided by the safety net. In particular, our results speak to the mitigating role of public assistance programs and tax credits, including Food Stamps or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), School Lunch, the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), public housing, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credits (CTCs), and social insurance programs—UI, and Social Security Old Age and Disability Income.

Ex ante, we would expect the safety net to partially offset the losses to PI in downturns. Aggregate program statistics show that the social safety net provided significant support to households affected by the Great Recession. In 2011, Food Stamp expenditures amounted to $72.8 billion and more than one in seven people in the United States received benefits from the SNAP program. The maximum duration of UI benefits was extended to up to 99 weeks during the Great Recession, far beyond the normal maximum of 26 weeks or even the Extended Benefit maximum of 52 weeks in most states. Further, at the center of the 2009 stimulus, there were temporary increases in the maximum benefits paid out for Food Stamps, the EITC, and UI, as well as in temporary tax relief (the Making Work Pay tax credit). The total cost of these expansions was over $200 billion.4

In addition to these important changes during the Great Recession, the social safety net for lower-income families has undergone a transformation since the last severe recessions, which took place during the early 1980s. Welfare reform in the mid-1990s led to a massive reduction in the share of families (Blank, 2002), and more specifically poor families (Floyd, Pavetti, & Schott, 2015), receiving cash welfare. At the same time, the EITC expanded substantially in generosity (Hotz & Scholz, 2003). The end result is that the U.S. safety net for low-income families with children has changed from one based on out-of-work assistance to one based on in-work assistance (Bitler & Hoynes, 2010, 2016; Moffitt, 2015). This may have important implications for the protective effects of the safety net for low-income households.

Our analysis yields several important findings. Using our ATT poverty measure, we find that child poverty rises in recessions and falls in expansions, and the level of cyclicality is higher at lower levels of the income distribution. Importantly, we find striking evidence that the safety net provides protection; that is, the cyclicality of ATT poverty is significantly attenuated relative to the cyclicality of PI poverty, controlling for fixed state characteristics and national shocks. The net result is that ATT child poverty rose modestly in the Great Recession, while child PI poverty increased substantially. These effects are not equal across groups, as we find that a given change in the unemployment rate leads to a higher probability that children fall into poverty in households headed by single parents, Hispanics, and, most significantly, for children in households with immigrant heads or spouses.

Our findings are robust to how we measure child poverty, including whether, instead of our Historical SPM threshold, we use the official poverty threshold (which is absolute), an “anchored” supplemental poverty threshold (Wimer et al., 2014, also absolute), or even the OECD's relative poverty measure (income less than 60 percent of the equivalized median yearly household income).5 In our main estimates, we exclude any value of public (and employer-provided) health insurance coverage from our measure of resources. Our results are robust to adding the Census Bureau's estimate of the fungible value of public health insurance (and a value for employer contributions to employer-provided insurance) or using the SPM approach of deducting from resources out-of-pocket medical expenses (as well as work expenses, including child care). The results are also robust to adding state-level time-varying policies, individual demographic controls, and state linear trends; as well as to not weighting by population, to using alternate lag structures for the effects of labor market shocks, and to an alternative definition of the sharing unit.

Our work adds to a large and rich literature on the measurement and determinants of poverty, spanning many decades (e.g., Blank, 1989, 1993; Blank & Blinder, 1986; Blank & Card, 1993; Cutler & Katz, 1991; Freeman, 2001; Gundersen & Ziliak, 2004; Hardy, Smeeding, & Ziliak, 2016; Hoynes, Page, & Stevens, 2006; Moffitt, 2012, 2015; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015). We contribute to this literature. First, we focus on child poverty and focus on the recent Great Recession period. Second, we analyze how the cyclicality varies as we move up the income-to-poverty distribution and quantify the role of the social safety net in mitigating losses. Third, we are the first to show the remarkable stability of the cyclicality across quasi-relative measures (our main results, using Historical SPM thresholds), absolute measures (official poverty thresholds and the anchored SPM thresholds), and relative measures (OECD thresholds), and all using an ATT measure of resources. Additionally, as suggested by Blank (2008) and Citro and Michael (1995) as well as many others (Fox et al., 2015a, 2015b), we come closer to capturing disposable income shared by children and adults by using a broader unit rather than the narrow Census family unit, and by counting post-tax-and-transfer income.6,7 We also complement recent work by Larrimore, Burkhauser, and Armour (2015), who focus on the stabilizing role of the safety net and the cycle in various recessions.8

The following section describes our data and how we measure poverty. Next, we provide a summary of the Great Recession and present the basic time series evidence on child poverty. Then, we describe the major social safety net programs and how they changed during the Great Recession, explore the cyclicality of poverty, examine the robustness of our main findings, and offer conclusions.

MEASURING CHILD POVERTY

Official poverty in the United States is measured using an absolute standard, in contrast to the relative poverty measure used in many other countries and the OECD (Burkhauser, 2009; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015). The U.S. official poverty measure is determined by comparing total pre-tax family cash income to poverty thresholds, which vary by family size, the number of children, and the presence of elderly persons. If the family has pre-tax cash income below the relevant threshold, then they are deemed to be poor. The family unit used for official poverty consists of all related individuals in the household;9 and all persons in the family have the same poverty status. In 2014, for example, the poverty threshold for a family of four (two adults plus two children) was $24,008 and 21.1 percent of children were poor.

The official poverty measure has numerous drawbacks (Blank, 2008; Citro & Michael, 1995). Of particular relevance for our work, the measure of family cash income is not a complete measure of family resources. It excludes non-cash government transfers (in-kind transfers such as food stamps and housing subsidies) as well as taxes and tax credits (notably the EITC and CTCs as well as other income and payroll taxes). Additionally, there is no geographic variation in the official poverty thresholds, despite wide variation in costs and wages across regions.10 These limitations in the official poverty definition have been noted for decades, and in 2011 the Census released a new poverty measure—the SPM—designed to improve on the official poverty measure (Short, 2011). The SPM resource measure expands to include the cash value of various in-kind transfers and nets out taxes (and deducts from income child support payments, medical out-of-pocket expenditures (MOOP) including health insurance premiums, and work expenses, including child care). Additionally, the SPM family unit is modified to include cohabitors and their children. The Census SPM thresholds are defined to be the average between the 30th and 36th percentiles of the distribution of consumer expenditures on food, clothing, shelter, and utilities, plus an additional 20 percent to account for additional necessary expenditures. This makes the SPM a “quasi-relative” poverty measure in that the threshold increases with consumption levels of families at the top of the bottom third of the consumption distribution. Additionally, the thresholds are adjusted to reflect geographic variation in housing costs and spending, owner versus rental status, and family size (Short, 2013).

In our analysis, we develop a poverty measure that is highly aligned with—though not identical to—the Census SPM. We use data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey (CPS), administered to most households in March every year. The ASEC is an annual survey that collects labor market, income, and program participation information for individuals for the previous calendar year, as well as demographic information from the time of the survey. Our sample uses the 2001 through 2015 CPS surveys, corresponding to the 2000 to 2014 calendar years. The CPS is used to report official poverty and, since 2011, the SPM each year.

We use the CPS to construct PI poverty and ATT poverty. Appendix Table A1 provides details on the sources of income in our two measures of resources and compares them to the income sources included in both official poverty and the Census SPM.11 Private income includes earned income, asset income, and private transfers (child support, alimony, private disability, and retirement). Our ATT resource measure, developed in Bitler and Hoynes (2010, 2016), includes PI plus cash transfers (AFDC/TANF, Social Security [Old Age and Disability income], SSI, UI, veterans payments, and workers’ compensation); the cash value (as reported by the household or imputed by the Census Bureau) of non-cash in-kind programs (food stamps, school lunch, housing subsidies, and energy subsidies); tax credits (the EITC, CTCs, and stimulus payments); and then subtracts payroll, federal, and state income taxes. We use the NBER TAXSIM model for all tax variables (though the results are virtually identical if we use the Census imputations of taxes provided in the CPS).

As is clear from Appendix Table A1,12 one way our ATT poverty measure differs from the Census SPM is that we do not incorporate MOOP or work-related expenses (including child care and other expenses), which are subtracted from resources by the Census SPM as are child support payments made. While there is significant agreement about the importance of adding the value of in-kind benefits to expand the resource measure, there are a variety of approaches that are used to take into account the value of public (and private) health insurance. The Congressional Budget Office, in its analyses of the concentration of and trends in income, uses the government's average cost of providing Medicaid and Medicare as well as employers’ contributions to health insurance to value health insurance (Congressional Budget Office, 2014). Until the SPM, the Census Bureau has used the fungible value of public health insurance, essentially counting the average cost of Medicaid and Medicare only if household income is above the amount needed for basic food and housing needs.13 Finally, the Census SPM deducts out-of-pocket medical expenses from income (rather than the CBO/Census approach of adding the value of the insurance coverage provided). In our view, none of these approaches satisfy the ideal of including the “insurance value” of this benefit as well as what families spend in practice. As such, in our main estimates we make no adjustment for MOOP or the value of public health insurance (or private health insurance). It turns out, as we show below, whether and how we handle this has no impact on the main results in the paper; results that either exclude MOOP (and other fixed costs of work) from resources or add the fungible value of Medicare and Medicaid and the value of employer-provided insurance premiums to resources are nearly identical to our main findings.

For each of our poverty measures, we calculate resources and poverty at the household level.14 This is another difference from the SPM—their sharing unit is composed of related individuals plus foster children and cohabitors and their children. However, the CPS only began identifying cohabitors for all of the adults in the household in 2007, and thus this measure is not available for our full sample period. Our household sharing unit also differs from one used by the Census to calculate official poverty, which consists of persons related by marriage, birth, or adoption. One advantage of our household measure is the inclusion of cohabitants and others who share resources. Additionally, the CPS only measures use of food stamps at the household level, so a household sharing unit is appealing for this reason.15 Therefore, private and ATT incomes are summed across household members and total household income is compared to the appropriate poverty threshold using the appropriate household structure and size; an indicator for this value being below the threshold is then attached to all household members. Since here we study child poverty, we limit the sample to those aged below 18 at the survey month. When we analyze subgroups, we use the demographic characteristics of the head of household (or in the case of immigration status, the spouse of the head as well).

Finally, we use the Historical SPM thresholds developed by Fox et al. (2015a) for our main poverty thresholds. The new Census SPM thresholds are only available beginning in 2009, so it is not adequate for our 2000 through 2014 analysis. Fox et al. (2015a) implement nearly all of the SPM methods and construct thresholds back to 1967 with available Consumer Expenditure Data. Due to data limitations, the Fox et al. (2015a) Historical SPM does not adjust the thresholds for geographic variation in costs and spending. Below, we explore the sensitivity of our main results to the poverty threshold, in particular also using the official U.S. poverty threshold, the “anchored” SPM (Wimer et al., 2014), as well as an OECD relative poverty threshold. Wimer et al. (2014) take the 2012 SPM threshold and backcast it by adjusting for changes in prices using the CPI-U-RS. For our measure of ATT poverty using the anchored SPM threshold, we take the same approach, starting with 2014 thresholds by household size and number of children, then collapsing to state (so the geographic variation matches our CPS data), and finally adjusting for changes in prices back to 2000.16 The OECD threshold is defined as 60 percent of the median of household-equivalized income. We implement this using our sample and resource measure and construct thresholds using the OECD's standard equivalence scale applied to the household structure and number of persons.17 This gives us one quasi-relative measure (ATT poverty with Historical SPM thresholds), two absolute measures (ATT poverty with official poverty thresholds or anchored SPM thresholds), and one relative measure (ATT poverty with OECD thresholds). As we show below, our main results are robust to using any of these four alternative thresholds to define poverty.

CYCLES, THE GREAT RECESSION, AND POVERTY

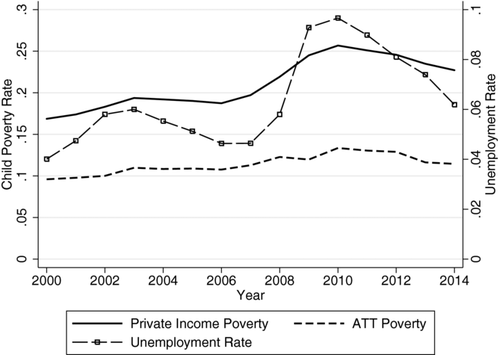

We begin with a historical view of child poverty and economic cycles, examining the changes in child poverty that have occurred in the U.S. between 2000 and 2014. Figure 1 presents (on the right axis) our primary measure of the economic cycle—the unemployment rate—annually over this period. Using the NBER dating, the Great Recession officially began in December 2007 and the unemployment rate rose from 5 percent in December 2007 to a peak of 10.0 percent in October 2009 (seasonally adjusted). While the recession officially ended in July 2009, it took another six years for the unemployment rate to return to its pre-Great Recession level, reaching 5.0 (seasonally adjusted) in October 2015 (not shown). Figure 1 also presents (on the left axis) our two measures of child poverty annually for the same period. The solid line plots annual child PI poverty and the dashed line plots child ATT poverty, both measured using the Historical SPM threshold. Notably, PI poverty varies significantly with the business cycle. Using this pre-tax-and-transfer measure of resources, during the Great Recession child PI poverty rose by 6.0 percentage points, from 19.7 in 2007 to 25.7 in 2010. Similarly, we see an increase in PI child poverty during the recession of the 2000s. Turning to the poverty measure calculated using the more comprehensive measure of resources, child ATT poverty rose (only) by 2.1 percentage points during the Great Recession (this change is from 2007—11.3—to 2010—13.4). This is our first evidence of the extent to which the social safety net provided protection against shocks to household earnings and income in the Great Recession.

Annual Unemployment Rate and Private Income Poverty and After-Tax-and-Transfer Poverty for Children.

Notes: Data are from the 2000 through 2014 calendar year ASEC (poverty measures) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (unemployment). Poverty refers to percentage of children living in households with income below the Historical SPM poverty line in each calendar year, using various concepts for resources. Private income includes only wages and salaries, self-employment income, and private transfers. ATT income includes the value of public in-kind and cash transfers and nets out taxes and tax credits.

In our main results, shown below, we explore these issues further by estimating the relationship between the business cycle and child poverty. In that analysis, we take advantage of the dramatic variation in the timing and magnitude of business cycles across U.S. states, controlling for fixed differences across states and aggregate secular trends. Here, we begin that analysis by presenting some descriptive findings on child poverty across states in the Great Recession. Figure 2 presents percentage changes in real PI, government transfers, and government taxes (net), by state, over the Great Recession. In particular, we compare the pre-recession peak (captured by averages over 2006 to 2008) to the trough (captured by averages over 2009 to 2011), following the Census practice of pooling multiple years to construct state averages.18 The figure shows that during the Great Recession average PI dropped for most states, but that transfers and taxes offset this drop. These changes represent average effects across all children of all income levels in the state. Figure 3 builds on this and shows the change in the child poverty rate, by state, where the changes are again over 2006 to 2008 to 2009 to 2011. For comparison, we present both poverty measures, with the solid bars representing ATT poverty and the open circles (with a line) representing PI poverty. During the Great Recession, almost all states experienced increases in PI child poverty, with North Dakota and its oil and gas boom representing a notable exception. The role of the safety net in providing protection against these PI losses is also evident in the figure. The net effect is a dramatic variation in the changes in child poverty across states in the wake of the Great Recession. Some states, such as many New England states (Connecticut, Massachusetts) and others (Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Texas), experienced reductions in ATT poverty. However, other states such as Nevada, District of Columbia, and Arizona experienced increases in ATT poverty on the order of 5 percentage points. The figure is a useful starting point, but the usual caveats apply given it is a “single difference” statistic. Importantly, these differences may, to some degree, be capturing short-run or longer-run trends as well as the cycle. We address these limitations by estimating a state panel model, described below.

Change in Average Child Household Income by Source and State in the Great Recession.

Notes: Data are from the 2006 to 2008 and 2009 to 2011 ASEC calendar years. Percentage changes in sources of income for children are computed as the percentage difference between the 2006 to 2008 weighted average of state household income from that source for children and the 2009 to 2011 weighted average of state household income for that source for children.

Change in Private Income Poverty and After-Tax-and-Transfer Poverty during the Great Recession for Children.

Notes: Data are from the 2006 to 2008 and 2009 to 2011 ASEC calendar years. Change in poverty refers to the change in the share of children in each state living in households with PI and ATT income below the Historical SPM poverty line. Changes in the share of children in poverty are computed as the difference between the 2006 to 2008 weighted average state poverty rate and the 2009 to 2011 weighted average state poverty rate.

THE SOCIAL SAFETY NET AND THE POLICY LANDSCAPE

In this section, we give a brief summary of the cash and non-cash social safety net for families with children and summarize the important policy changes leading up to and during the Great Recession. We consider a broad definition of the social safety net including traditional means-tested cash programs (TANF, SSI), near-cash in-kind means-tested transfers (SNAP—formerly known as Food Stamps—housing subsidies, LIHEAP, child nutrition programs), tax credits (the EITC, the CTCs), and, in some specifications, means-tested public health insurance (Medicaid, Children's Health Insurance Program).19 Additionally, we consider unemployment insurance, given its prominent place as income replacement after job loss (even though, unlike all of the above, it is not a program targeted to lower-income groups). We also consider elements of the temporary stimulus programs (implemented in 2008 and 2009). We choose these tax and transfer programs to comprise our working definition of the social safety net because of our ability to measure them in our household data (the CPS) along with their importance for low-income households with children (Moffitt, 2015; Short, 2015).20

These programs are summarized in Table 1, which presents the total cost (in billions) of each program in 2010, the trough of the recession. In 2010, UI spending topped the list at $150 billion, although, as a social insurance program, it serves workers throughout the income distribution. The combined amount spent on tax credits, the EITC and the refundable portion of the CTC, amounted to $87.3 billion, followed by SNAP at $64.8 billion. Housing assistance (Section 8 and public housing) was $27.3 billion. Much smaller is cash welfare, $12.4 billion for TANF and $9.4 billion for SSI (limited to costs for covering children), and the other child food and nutrition programs.21 Medicaid expenditures (limited to costs for covering children) were $67.2 billion.

| Billions of dollars | |

|---|---|

| Public assistance, cash | |

| TANF, cash assistance | $12.4 |

| SSI, recipients <18 | 9.4 |

| Public assistance, food and nutrition programs | |

| SNAP | 64.8 |

| National School Lunch Program | 9.8 |

| Tax credits | |

| EITC | 59.6 |

| CTC (primarily higher income filers) | 28.5 |

| Additional CTC (refundable) | 27.7 |

| Public assistance, other in-kind | |

| Housing (Section 8, public housing) | 27.3 |

| Medicaid, recipients <18 | 67.2 |

| LIHEAP | 5.1 |

| Social insurance | |

| UI (regular, extended, emergency, & STC) | 150.0 |

- Notes: Table shows total spending in billions of 2010 dollars on various transfer programs and tax credits. Source for TANF cash assistance spending for FY 2010: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family Assistance (2016); for SSI spending for children, 2010: Social Security Administration (2016); for SNAP for FY 2010: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (2016a); for School Lunch for FY 2010: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (2016b); for EITC and CTC for 2010: Internal Revenue Service (2016); for Housing for FY 2011 in 2011 dollars: Congressional Research Service (2012); for Medicaid for 2010: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2013); and for UI for 2010: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment & Training Administration (2016).

Before proceeding, we lay out what we do and do not seek to causally identify in our analysis. First, we use variation in the timing and severity of economic cycles across states to estimate the effects of the unemployment rate on various multiples of the child poverty threshold. By exploring the probability that children are in households under 50, 100, 150, and 200 percent of poverty, we identify how the cyclicality of income-to-poverty varies along the income-to-poverty distribution. Second, we evaluate the role of the social safety net by comparing the cyclicality of PI poverty to that of ATT income poverty. The aim of the paper is not to estimate the effects of the policies and programs, per se, but, instead, the effects of the cycle and how the programs mitigate the shocks associated with the cycle. Our reduced-form analysis does incorporate behavioral responses to the labor market shock, such as changes in employment and earnings of a spouse, and changes in living arrangements.

The Social Safety Net

Cash Welfare (AFDC/TANF)

Since 1935, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) provided cash welfare for single-parent families with children. The program is means-tested, requiring families to satisfy income and asset tests. The benefits were structured in a manner typical for income-support programs: if a family had no income, they received the maximum benefit (guarantee), and as earnings increased the benefit was reduced by the benefit reduction rate. The benefit reduction rate was high for AFDC, 67 or 100 percent, providing strong disincentives for work (Moffitt, 1983). Concerns about work disincentives and disincentives to form two-parent families led to federal welfare reform, with enactment of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWRORA) in 1996. TANF, the program that replaced AFDC, includes work requirements (with financial sanctions for non-compliance), a maximum of five years of lifetime use of federally funded welfare, and, in many states, enhanced earnings disregards. Importantly, welfare reform removed the entitlement to AFDC and federal funding was replaced with a (nominally fixed) block grant, and states were given more flexibility to spend this funding on things besides cash assistance. Under both AFDC and TANF, benefits are relatively low; for example, in 1996, on the eve of welfare reform, the median state's benefit level was about 36 percent of the poverty guideline (U.S. House of Representatives, 1996). Since welfare reform, caseloads have fallen to historic lows; for example, the number of families receiving cash welfare (TANF/AFDC) per 100 families with children in poverty fell from 68 in 1996 to 23 in 2014 (Floyd, Pavetti, & Schott, 2015).

Food Stamps (SNAP)

Like AFDC/TANF, Food Stamps is a means-tested program and benefits are based on maximum benefit level that is reduced with additional earnings using a benefit reduction rate. The SNAP, as the program was renamed in 2008, provides a voucher that can be spent on most food items in the grocery store.22 In contrast to AFDC/TANF, SNAP is a federal program with little involvement and few rules set by the states until quite recently, with a national income eligibility threshold and benefits being adjusted for changes in prices each year. SNAP is close to a universal program with eligibility extending to almost all those that meet the income and asset rules. The benefit reduction rate for SNAP is relatively low (30 percent); the gross income eligibility threshold is higher (at 130 percent of poverty) than other U.S. cash welfare programs, and the program serves the working and non-working poor. Welfare reform left Food Stamp rules relatively unaffected.23 However, beginning with regulatory changes in 1999 and continuing with the 2002 Farm Bill, the USDA has allowed states to make changes in how they implement the program's rules to facilitate obtaining access to benefits. This has led to a relaxation of asset requirements and expanded gross income eligibility in what has been called broad-based categorical eligibility (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2007). Overall, SNAP spending increased substantially in the Great Recession (Bitler & Hoynes, 2016) and provides an automatic stabilizer for families and the broader economy. In 2014, SNAP provided benefits to 47 million persons in 22.7 million households.

Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

SSI is a means-tested program providing cash benefits for low-income aged and disabled individuals. A 1990 Supreme Court decision relaxed the medical eligibility criteria for children and the SSI-child caseload has steadily grown since that time. Benefits for child SSI recipients averaged $561 per month in April 2016 and about 1.3 million children currently receive the benefits (Social Security Administration, 2016).

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

The EITC is a tax credit available to lower-income families with positive earned income. It is refundable, so when a family's income is too low to generate tax obligations, the EITC liabilities are negative and the family receives a refund check from the Internal Revenue Service. The EITC schedule has three segments: the phase-in, flat, and phase-out ranges. At low earnings (in the phase-in range), the EITC functions as an earnings subsidy with subsidy rates of 34/40/45 percent for families with one/two/three or more children. At higher levels of earnings, beyond a narrow flat region, the credit is phased out at around a 21 percent phase-out rate. Expansions of the EITC, facilitated through tax acts in 1986, 1990, and 1993, have featured prominently in the movement toward more “in-work” assistance in the U.S. safety net (and with welfare reform, a decline in out-of-work assistance). In 2015, for a single mother with two children, the maximum EITC credit was $5,548 (annual payment) and the phase-out range extended to those with earned income of up to $44,454. In 2013, about 22 million families with children received the EITC with an average payment of $3064 (Internal Revenue Service, 2016).

Child Tax Credit (CTC)

The CTC was introduced in 1997. It is structurally similar to the EITC (with a phase-in, flat, and phase-out range), but more universal in design and less targeted toward lower-income families. Since 2003, the maximum credit is $1,000 per child (it is set nominally and, unlike the EITC, does not change with prices each year). The CTC's wide flat region (where the credit is maximized at $1,000) and a low phase-out rate (5 percent) combine to generate high-income eligibility limits: in 2015, the CTC was available to families with incomes up to $150,000 (if married with two children) or $115,000 (if single with two children). The CTC is a nonrefundable credit, which limits the value of the credit for low-income families (who are less likely to have positive tax liabilities). However, a refundable CTC (called the Additional CTC) was introduced in 2001 and expanded significantly in 2009 as part of the stimulus (and recently became permanent). Currently, the Additional CTC provides a refundable credit equal to 15 percent of earnings above $3,000. This has significantly enhanced the benefits of the CTC for lower-income families (Hoynes & Rothstein, 2016).

Unemployment Insurance (UI)

Unemployment insurance provides temporary and partial earnings replacement for involuntarily unemployed individuals with recent employment. As a social insurance program, UI is not means-tested (limited to those with low incomes) and eligibility is a function of earnings history. UI benefits consist of three separate programs. Recipients receive benefits for a fixed duration, typically up to 26 weeks, through regular state benefits, funded by employer contributions. Under the Extended Benefits program, jointly funded by states and the Federal government, UI benefits can be extended for 13 or 20 additional weeks in states experiencing high unemployment rates. Lastly, in most major downturns, Congress has enacted emergency extensions to unemployment; these programs tend to be relatively short-lived and are explicitly counter-cyclical and fully federally funded.

The CPS data also allow for measurement of housing subsidies and the National School Lunch Program, both means-tested transfer programs for income-eligible families, as well as subsidies for spending on energy (LIHEAP). In some specifications, we include the Census measure of the “fungible value” of public health insurance for children and parents, Medicaid, and the Children's Health Insurance Plan (CHIP).24 Originally, Medicaid was limited to families (and individuals) who received cash welfare (now TANF or SSI). However, with policy expansions in the mid-1980s through the 1990s, Medicaid (and subsequently, post-1997, CHIP) expanded to children (and pregnant women) beyond those participating in cash welfare (Gruber, 1997). The number of children enrolled in Medicaid now totals 32.7 million (in fiscal year 2011) almost a tripling from the 11.2 million in 1990 (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2013).

This discussion makes clear that heading into the Great Recession, the social safety net has moved away from cash welfare and toward tax credits and in-kind transfers. This represents a major change in support for low-income Americans.

The Stimulus and Changes to the Social Safety Net in the Great Recession

The ARRA of 2009 was passed in February 2009 and contained many elements that expanded the social safety net. The Food Stamp maximum monthly benefit was increased by 13.6 percent (this provision expired in October 2013) and the three-month time limit on Food Stamp receipt for able-bodied childless adults (ABAWDs) was suspended temporarily (states can also seek waivers if the local unemployment rate exceeds a threshold or if there are insufficient jobs). The 2009 ARRA also included a $5 billion TANF emergency fund (temporarily expanding the block grant), expanded the EITC to include a more generous schedule for families with three or more children, expanded the refundable portion of the CTC, and reduced taxes through the introduction of the Making Work Pay Tax Credit (providing up to $400 per worker).25 There was also a 2008 Economic Stimulus that included a “recovery rebate” with maximum payments of $600 ($1,200 for joint filers).

In the Great Recession, both extended and emergency programs provided extensions to the duration of UI (Rothstein, 2011). In June 2008, Congress enacted the Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program, which (eventually) raised maximum UI benefit durations to as long as 99 weeks, given sufficiently high unemployment rates in the states. With passage of the 2009 ARRA, the full cost of extended benefits was shifted to the federal government; the ARRA also raised the weekly UI benefit by $25.26 These UI extensions expire when the unemployment rate within states declines below certain predetermined thresholds. Some states have responded to the slow recovery by cutting the maximum duration of their state benefits (e.g., North Carolina now has a maximum state duration of 19 weeks), while sequestration also led to some reductions in EUC benefits.

Implications for Low-Income Households

To gain some insight into the quantitative importance of these elements of the safety net for households with children, Figure 4 presents a summary of income components by source for our sample of children from the CPS. In particular, we calculate the share of total ATT income by source for children living in deep poverty (resources less than 50 percent of poverty, panel A), below 100 percent of poverty (panel B), below 150 percent of poverty (panel C), and below 200 percent of poverty (panel D). In each panel, we plot the percentage of total ATT income from the following sources: earned income, TANF,27 SSI, EITC and both CTCs, Food Stamps, other in-kind benefits (school lunch, housing subsidy, LIHEAP), UI, and others.28 We plot this for 2010, the trough of the Great Recession in terms of the U.S. annual unemployment rate. Several facts emerge from these graphs. First, TANF is providing minimal income; even for those in deep poverty, cash assistance (TANF plus general assistance) is only 4.2 percent of total income. SNAP, on the other hand, makes a significant contribution to incomes for those under 50, 100, and 150 of poverty, ranging from 23.3 percent of income for those under 50 percent of poverty to 19.6 percent for those under 100 percent of poverty, to 13.0 percent for those under 150 percent of poverty. The share of income from SSI ranged from 2.7 percent for those under 50 percent of poverty to 4.6 percent for those under 100 percent of poverty. Second, the tax-based safety net is important: the importance of the EITC (and both CTCs) is particularly evident at 100 percent poverty and beyond, supplying 9.3 percent of ATT income for those under 100 percent of poverty, 13.2 percent of ATT income for those under 150 percent of poverty, and 12.6 percent of ATT income for those under 200 percent of poverty. UI, on the other hand, is small in magnitude at all of these income-to-poverty levels and is never more than 4.5 percent of income at 100 percent poverty and above, and is only 2.8 percent of income for those in deep poverty.29

Composition of After-Tax-and-Transfer Income by Source for Children, 2010. (a) Below 50% Poverty. (b) Below 100% Poverty. (c) Below 150% Poverty. (d) Below 200% Poverty.

Notes: Data are from the 2011 ASEC (income from calendar year 2010). Poverty multiples refer to the sample of children living in households with income below multiples of the Historical SPM poverty line, using ATT income. The percentages sum to 100. Other in-kind sources are school lunch, the value of housing subsidies, and LIHEAP. “Other” sources of income include Social Security (Old Age and Disability benefits), veterans payments, workers’ compensation, unearned private income (asset income, child support, alimony, private retirement and private disability), and federal and state taxes other than the EITC and Child Tax Credits.

These findings are consistent with those in the Census report on the SPM (Short, 2015). The report shows that the combined tax credits (EITC and CTC) are the biggest anti-poverty program for children, keeping 5 million children out of poverty. The second biggest anti-poverty program for children is SNAP, which keeps 2.2 million children out of poverty. These reductions are followed in magnitude by a decrease in children in poverty of 1.5 million for Social Security (retirement and disability), 1.0 million for public housing, 0.7 million for school lunch, 0.7 million for SSI, 0.6 million for UI, and 0.4 million for TANF.30

Putting this all together, there are several important observations about the social safety net for low-income households going into the Great Recession. First, with welfare reform and the expansion of the EITC, the safety net for low-income households with children has been transformed from one providing out-of-work assistance into one supporting in-work assistance. Second, a large and growing share of the cost of the social safety net is accounted for by public health insurance (Congressional Budget Office, 2013). Third, the stimulus expanded significantly the core programs aimed at protecting income from earnings losses.

THE CYCLICALITY OF POVERTY

(1)

(1) is the state unemployment rate in state s and year t; and equation 1 also controls for state and year fixed effects,

is the state unemployment rate in state s and year t; and equation 1 also controls for state and year fixed effects,  and

and  respectively. We cluster the standard errors at the state level, and the regressions are weighted using the relevant denominator (the CPS total weighted population of children in the state-year cell). Below, we consider the robustness to alternative measures of the economic cycle, to adding time-varying state policies (Zst) as well as to adding lags of the unemployment rate and state linear trends and individual controls.

respectively. We cluster the standard errors at the state level, and the regressions are weighted using the relevant denominator (the CPS total weighted population of children in the state-year cell). Below, we consider the robustness to alternative measures of the economic cycle, to adding time-varying state policies (Zst) as well as to adding lags of the unemployment rate and state linear trends and individual controls.Main Findings

Our main results are presented in Table 2. The first four columns present results for the child PI poverty and the second four columns present results for child ATT poverty. To explore the impacts of the cycle at different points of the income-to-poverty distribution, we present models for the share of children with (private or ATT) income below 50, 100, 150, and 200 percent of the poverty level. We use the Historical SPM as the poverty threshold (Fox et al., 2015a). Reported in Table 2 is the estimate of the coefficient β that captures the extent to which within-state over-time changes in poverty respond to within-state over-time changes in the state unemployment rate.

| Private income poverty | After-tax-and-transfer poverty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50% | <100% | <150% | <200% | <50% | <100% | <150% | <200% | |

| UR | 0.509 | 0.871 | 0.988 | 0.978 | 0.198 | 0.538 | 0.928 | 0.959 |

| (0.097) | (0.134) | (0.152) | (0.165) | (0.057) | (0.096) | (0.157) | (0.151) | |

| Percentage impact | 4.8 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| Mean y | 0.107 | 0.212 | 0.326 | 0.432 | 0.031 | 0.114 | 0.255 | 0.417 |

| Mean UR | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| N | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

- Notes: Table shows the relationship between children having household private income (columns 1 through 4) or after-tax-and-transfer income (columns 5 through 8) below various multiples of the Historical SPM poverty threshold and the state unemployment rate. Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 to 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted). All regressions include controls for state and year fixed effects. The results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell. Standard errors are clustered by state and shown in parentheses.

The first thing to note is that all of the coefficients in Table 2, for both PI poverty and ATT poverty, are positive and statistically significant, showing a high degree of cyclicality of child poverty consistent with the existing literature (Bitler & Hoynes, 2010, 2016; Blank, 1989, 1993; Blank & Blinder, 1986; Blank & Card, 1993; Cutler & Katz, 1991; Freeman, 2001; Gunderson & Ziliak, 2004; Hoynes, Page, & Stevens, 2006; Meyer & Sullivan, 2011). Our estimates here update that previous work using data through the Great Recession, focus on child poverty, and contrast before-tax-and-transfer and ATT poverty.

Looking at the first four columns (for child PI poverty), the results show that a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a 0.9 percentage point increase in the probability that PI is below 100 percent of poverty for a 4.1 percent effect (relative to mean child PI poverty of 21.2 percent). The sensitivity of child PI poverty to changes in unemployment is the largest at the bottom of the distribution and decreases as we move up to higher poverty levels. The percentage impacts of a 1 percentage point increase in unemployment rate are 4.8 percent for less than 50 percent of poverty, and 4.1, 3.0, and 2.3 for less than 100, 150, and 200 percent of poverty, respectively.31

Columns 5 through 8 present similar models for child ATT poverty. Before comparing the results, the difference in the mean poverty rates illustrates the importance of the social safety net for low-income households. For example, 10.7 percent of children have PI below 50 percent of poverty while a much lower 3.1 percent of children have ATT income below 50 percent of poverty. For 100 percent of poverty, 21.2 percent of children have PI below this level compared to 11.4 based on ATT income. The differences narrow as we move higher in the income-to-poverty distribution (32.6 vs. 25.5 percent for 150 percent of PI and ATT poverty, and 43.2 vs. 41.7 percent for 200 percent of PI and ATT poverty). This “tilting” of the income-to-poverty gradient reflects the high levels of various safety-net program benefits and tax credits at the lowest income levels and the potentially offsetting effects of taxes and non-cash benefits for the higher income levels.32

Comparing the results on the cyclicality of PI poverty (columns 1 through 4) and ATT poverty (columns 5 through 8), we see strong evidence for the safety net in protecting income, particularly at the lowest income levels. For deep poverty (income below 50 percent of the poverty threshold), the results show that a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a 0.2 percentage point increase in the level of ATT poverty, compared to the 0.5 percentage point increase in PI poverty. For 100 percent of poverty, the results show that a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a 0.5 percentage point increase in ATT poverty, compared to a 0.9 percentage point increase in PI poverty. This reduction in the cyclicality of poverty is an illustration of the magnitude by which the social safety net provides protection against shocks to earnings and income. These results illustrate our main findings: the social safety net mitigates the income loss due to the Great Recession (and the much less severe 2001 recession), and reduces, in particular, the exposure for those at the lowest income-to-poverty levels.33

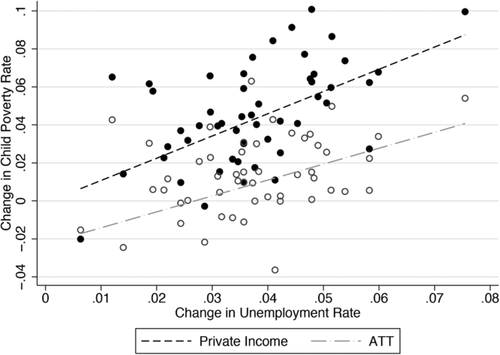

Figure 5 illustrates some of the variation underlying these regression estimates. The figure provides a scatterplot where the x-axis shows the change in the state unemployment rate (UR, as a share) and the y-axis shows the change in child PI (100 percent) poverty (filled circle) and child ATT (100 percent) poverty (open circle). Each point is a state's pair of values, and we plot the changes in UR and poverty over the Great Recession (peak over 2006 to 2008 to trough over 2009 to 2011).34 We also provide a best-fit line (using the child population in each state as weights) of these points.35 There are several things to point out with the figure. First, there is substantial variation in the severity of the labor market shock in the Great Recession across states—for example North Dakota, Alaska, and Nebraska experienced an increase in the UR of less than 1.5 percentage points, while Alabama, California, Florida, and Nevada had increases of more than 5.5 percentage points. It is this variation in the unemployment rates (as well as the year-to-year timing of the changes) that provides the identification in our model. Second, and importantly, the figure helps to visualize the effect that the social safety net plays in mitigating the increases in poverty from the Great Recession. The slope of the line for PI poverty is much steeper (dashed line) than the slope for ATT poverty (solid line). Thus, the relationship between the size of the shock and the resulting change in child poverty is significantly lessened by incorporating the stabilizing effects of the social safety net. In both cases, the relationship between changes in the unemployment rates and changes in poverty is positive, but the correlation is larger for PI poverty compared to ATT poverty.

Change in Unemployment Rate and Child ATT Poverty in the Great Recession, by State.

Notes: Data are from the 2006 to 2008 and 2009 to 2011 ASEC (calendar year income) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Poverty refers to percentage of children living in households with PI or ATT income below the Historical SPM poverty line. Changes in poverty rates and unemployment rates are computed as the differences between the weighted state average child poverty and unemployment rate (as a share) for 2006 to 2008 and the weighted state average child poverty and unemployment rate (as a share) for 2009 to 2011.

To explore the role of the social safety net further, Table 3 separates out the public assistance safety net and the social insurance safety net. Columns 1 through 4 repeat the results for PI poverty and columns 5 through 8 add social insurance (or, more accurately, all non-means-tested taxes and transfers, which excludes the EITC, the CTC and refundable additional CTC and other credits). Columns 9 through 12 then add means-tested tax and transfer programs, arriving at ATT poverty.36 Table 3 shows the expected pattern in terms of the point estimates. As social insurance payments are added, the cyclicality of income to poverty decreases at all levels, though modestly. Adding public assistance and tax credits, in contrast, leads to a substantial decrease in cyclicality at 50 and 100 percent poverty (with smaller changes at the higher income-to-poverty levels).

| Resource measure: | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private income | Private income + Social insurance | ATT income | ||||||||||

| <50% | <100% | <150% | <200% | <50% | <100% | <150% | <200% | <50% | <100% | <150% | <200% | |

| UR | 0.509 | 0.871 | 0.988 | 0.978 | 0.351 | 0.806 | 0.803 | 0.910 | 0.198 | 0.538 | 0.928 | 0.959 |

| (0.097) | (0.134) | (0.152) | (0.165) | (0.114) | (0.138) | (0.163) | (0.156) | (0.057) | (0.096) | (0.157) | (0.151) | |

| Percentage impact | 4.8 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| Mean y | 0.107 | 0.212 | 0.326 | 0.432 | 0.086 | 0.195 | 0.325 | 0.454 | 0.031 | 0.114 | 0255 | 0.417 |

| Mean UR | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| N | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

- Notes: Table shows the relationship between children having household private income (columns 1 through 4), household income and social insurance (columns 5 through 8), or after-tax-and-transfer income (columns 9 through 12) below various multiples of the Historical SPM poverty threshold and the state unemployment rate. “Social insurance” includes all tax and transfer programs not explicitly means tested, this includes federal income taxes (except EITC, CTC, Additional CTC and other credits). Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 to 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted). All regressions include controls for state and year fixed effects. The results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell. Standard errors are clustered by state and shown in parentheses.

To explore how these results vary across different groups, Table 4 presents ATT 100 percent poverty for demographic subgroups. We define subgroups based on characteristics of the household head (in most cases, the parent) including marital status, race/ethnicity, and immigrant status (here, of the household head or their spouse). Prior work shows that racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to suffer labor market shocks (e.g., Hoynes, Miller, & Schaller, 2012). Additionally, single-headed households and racial and ethnic minorities have higher baseline poverty rates. Importantly, for immigrants, another issue is that a large share of the safety net is either unavailable to them (unauthorized immigrants) or access is more limited (authorized immigrants).37 Given all of this, we would expect ATT poverty to be more responsive for households headed by non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics than for non-Hispanic white-headed households, and for households with single versus married heads. But we would also expect the safety net to be less responsive and less effective at mitigating shocks for households headed by immigrants or with an immigrant spouse (compared to households with native heads/spouses), due to their more limited access to the safety net.

| Child ATT 100% poverty | Child 100% poverty | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Single | White | Black | Hispanic | Immigrant PI poverty | Immigrant ATT poverty | Native PI poverty | Native ATT poverty | |

| UR | 0.490 | 0.645 | 0.363 | 0.492 | 1.119 | 1.197 | 1.171 | 0.724 | 0.358 |

| (0.099) | (0.191) | (0.092) | (0.357) | (0.218) | (0.467) | (0.250) | (0.119) | (0.109) | |

| Percentage impact | 8.5 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 4.5 | 8.3 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Mean y | 0.057 | 0.250 | 0.065 | 0.226 | 0.183 | 0.265 | 0.141 | 0.197 | 0.107 |

| Mean UR | 0.064 | 0.065 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| N | 5,791 | 5,024 | 2,827 | 2,459 | 2,854 | 4,956 | 4,956 | 5,859 | 5,859 |

- Notes: Table shows the relationship between child private income poverty or after-tax-and-transfer poverty and the state unemployment rate across demographic groups. The poverty threshold is the Historical SPM. Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 to 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year-by-demographic group level (weighted). All regressions include controls for state and year fixed effects. Demographic groups are determined according to the demographics of the household head, or in the case of immigration, whether the head or their spouse are immigrants. The results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell. Standard errors are clustered by state and shown in parentheses.

The findings in Table 4 are consistent with these predictions. A 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to larger increases in poverty for children whose head of household is single (compared to married), and for children of black and Hispanic household heads (compared to children of white heads).38 Most dramatic, however, is the comparison of children of native and children of immigrant household heads/spouses. The cyclical responsiveness of poverty for children of immigrant heads/spouses is larger in absolute and percentage terms than that for children of natives, for both the PI and ATT measures. Even more striking, adding in the income from the social safety net has no mitigating effect—in fact, a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate leads to a similar 1.2 percentage point increase in both PI and ATT poverty. Appendix Table A2 shows the results for PI poverty and ATT poverty for the subgroups in columns 1 through 5 of Table 4, and the only other group where the cyclicality of poverty does not significantly decrease when we include taxes and transfers in the measure of income is Hispanics.39 Although not shown here, this same pattern for children of immigrant heads/spouses is evident for extreme poverty as well.

ROBUSTNESS

Here we explore the sensitivity of our main findings to two changes to our poverty definition as well as examine the sensitivity of our results to the basic model specification.

Sensitivity to Alternative Poverty Measures

Our baseline results are based on our ATT poverty using the Historical SPM thresholds (Fox et al., 2015a). We compare these results to those using two different absolute poverty thresholds, our version of the anchored SPM thresholds (Wimer et al., 2014) and the official poverty thresholds. We also explore the cyclicality of a relative poverty measure. To do so, we adopt the poverty definition used by the OECD: a person is poor if their income is below 60 percent of the median of household-equivalized income. This threshold is recalculated each year and thus reflects relative income inequality rather than an absolute measure. The results for PI and ATT 100 percent poverty across these four measures for the thresholds are presented in Table 5. Looking across the columns, we find a remarkable consistency in the cyclicality of poverty across the different measures, in absolute and percentage terms. Additionally, across the measures we find very similar effects of the social safety net (comparing PI to ATT poverty). Figure 6 illustrates this robustness more fully, by presenting the coefficients for these alternative measures for the four different income-to-poverty cutoffs (the estimates and standard errors are reported in Appendix Table A3).40 Across these four panels, our main findings stand out. The social safety net mitigates the effects of cyclical downturns, particularly at the lower end of the income distribution (50 and 100 percent of poverty). This holds regardless of whether we use the Historical SPM thresholds, the anchored SPM thresholds, or official poverty thresholds. It also holds for a quite different construct, the OECD relative poverty thresholds.41

| SPM historical | SPM anchored | Official poverty | OECD measure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | ATT | PI | ATT | PI | ATT | PI | ATT | |

| UR | 0.871 | 0.538 | 0.892 | 0.461 | 0.859 | 0.478 | 1.075 | 0.975 |

| (0.134) | (0.096) | (0.124) | (0.109) | (0.137) | (0.114) | (0.193) | (0.150) | |

| Percentage impact | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Mean y | 0.212 | 0.114 | 0.212 | 0.117 | 0.201 | 0.105 | 0.348 | 0.290 |

| Mean UR | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| N | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

- Notes: Table shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and children having household private income after-tax-and-transfer income below the Historical SPM threshold (columns 1 and 2), the anchored SPM threshold (columns 3 and 4), the official poverty threshold (columns 5 and 6) and the OECD poverty threshold (columns 7 and 8). Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 to 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted). All regressions include controls for state and year fixed effects. The results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell. Standard errors are clustered by state and shown in parentheses.

Effects of Unemployment Rate on Private Income Child Poverty and After-Tax-and-Transfer Child Poverty—Sensitivity to the Choice of Poverty Threshold. (a) Below 50% Poverty. (b) Below 100% Poverty. (c) Below 150% Poverty. (d) Below 200% Poverty.

Notes: Figure shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and children having household private income or after-tax-and-transfer income below various multiples of the Historical SPM threshold, the anchored SPM threshold, the official poverty threshold and the OECD poverty threshold (the coefficient on the unemployment rate). Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 through 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted).

Table 6 explores the sensitivity of our results to the treatment of costs and benefits of medical care and insurance. Our baseline measure of resources used to construct ATT poverty (see the definitions of the poverty measure resource definitions in Appendix Table A1) does not include the benefits of health insurance (public or employer-provided) nor does it include the out-of-pocket medical costs (or other fixed costs of work).42 Table 6 presents two alternatives prominent in the literature. First, we adopt the Census approach used for most of the period prior to the introduction of the Census SPM (experimental poverty measure as suggested by the National Academy of Sciences). This adds to ATT income the fungible value of Medicaid (and Medicare and includes the value of the employer contribution to HI premiums). Second, we use the approach in the Census SPM and deduct from ATT income out-of-pocket medical costs (here we also deduct work-related expenses including child care costs as is implemented in the SPM). The results, for 100 percent poverty using both the historical and anchored SPM thresholds, are shown in Table 6. By looking at the means of the dependent variable across the columns in the table, it is clear that how one treats the costs and benefits of medical care and insurance makes a difference in the level of the measured child poverty rates. However, the table shows clearly that our core finding concerning the cyclicality of poverty, quantitatively and qualitatively, is little changed by how we treat medical care. Figure 7 expands this analysis to illustrate how these results vary across income-to-poverty thresholds in percentage terms (the full set of coefficients and standard errors, including those for the ATT poverty with anchored SPM thresholds are presented in Appendix Table A4).43 The figure confirms our main finding that the percentage effects of an increase in unemployment decline as we move up the income-to-poverty distribution.

| SPM historical | SPM anchored | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT+ | ATT– | ATT+ | ATT– | |||

| ATT | Medical | MOOP | ATT | Medical | MOOP | |

| UR | 0.512 | 0.490 | 0.662 | 0.441 | 0.500 | 0.517 |

| (0.095) | (0.094) | (0.102) | (0.105) | (0.107) | (0.111) | |

| Percentage impact | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 3.8 | 4.7 | 3.6 |

| Mean y | 0.114 | 0.106 | 0.142 | 0.117 | 0.106 | 0.145 |

| Mean UR | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 | 0.064 |

| N | 714 | 714 | 714 | 714 | 714 | 714 |

- Notes: Table shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and children having household private income or after-tax-and-transfer income below the Historical SPM thresholds (columns 1 through 3) and anchored SPM thresholds (columns 4 through 6). Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 to 2013 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted). Column 1 and 4 specifications are for the determinants of poverty using our baseline ATT measure of resources; column 2 and 5 specifications are for the determinants of poverty using a resource measure that adds the fungible value of Medicaid/CHIP and Medicare and the employer contribution to HI premiums to ATT resources; and column 3 and 6 specifications are for the determinants of poverty after subtracting MOOP, child care expenses, and other work expenses from ATT resources. All regressions include controls for state and year fixed effects. The results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell. Standard errors are clustered by state and shown in parentheses.

Sensitivity of ATT Poverty Cyclicality to Treatment of Medical Benefits, Historical SPM Thresholds.

Notes: Figure shows the relationship between having household after-tax-and-transfer income below various multiples of the Historical SPM poverty threshold and the state unemployment rate, using various measures of resources to construct the poverty measures. First set of bars are percentage effects using an ATT measure of resources; second set of bars are percentage effects using a resource measure that adds the fungible value of Medicaid/CHIP and Medicare and the employer contribution to HI premiums to ATT resources; and the third set of bars subtracts MOOP, child care expenses, and other work expenses from ATT resources. Data are from the CPS ASEC calendar years 2000 through 2014 and are collapsed to the state-by-year level (weighted). All effects from regressions that include controls for state and year fixed effects, and percentage effects derived by dividing the estimated coefficient on the unemployment rate by the average of the dependent variable. The regression results are weighted by the sum of the CPS weights in the cell.

Sensitivity to Alternative Model Specifications

First, we explore the sensitivity to adding controls for demographic characteristics, state-level time-varying policies, and state linear trends to our relatively parsimonious estimation model. The results are shown in Appendix Table A5.44 Our first set of robustness (panel B) turns to individual regressions and adds controls for the head's characteristics, including dummies for single years of age; dummies for race/ethnicity (Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, other non-Hispanic); a dummy for marital status (head is married); a dummy for the head being male; and dummies for the head's education being high school graduate, some college, and college graduate. While these need not look identical to our aggregate regressions, these individual controls make little difference to our findings. We also explore how state policy choices in Medicaid (eligibility limits for pregnant women and children), state-level EITCs, the average UI replacement rate (Kuka, 2016), TANF (the guarantee), and the real level of the binding minimum wage affect our estimates. Controlling for these important poverty determinants has little substantive effect on our estimates of cyclicality of any of our poverty measures (panel C). Similarly, including state linear trends does not significantly affect our estimates (panel D).

Next, we explore the sensitivity to our choice of the unemployment rate as the measure of the cycle. Appendix Table A6 presents our baseline results, followed by panel B with the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) as the measure of the state-year cycle, and panel C with real chained GDP per capita as the measure of the cycle.45 We present results for PI and ATT poverty and for the four cuts of income-to-poverty. Broadly speaking, the qualitative findings are similar regardless of whether we use the unemployment rate or EPOP as our measure of the cycle. All coefficients for the effect of the business cycle on poverty are counter-cyclical and highly statistically significant (the coefficients on the EPOP and GDP per capita are negative, indicating a strengthening of the labor market leads to a reduction in poverty), and the magnitudes of the percentage impacts are strikingly similar for the unemployment rate and EPOP (in absolute value).46 The results show that GDP per capita is not a statistically significant determinant although all but one of the signs are consistent with those for the unemployment rate and EPOP; when the coefficient for the unemployment rate is positive, that for the GDP is negative seven out of eight times and that for EPOP is always negative. We also explored including the Census's imputed tax measures instead of assigning the TAXSIM values, not weighting by the population of children, and using an alternate sharing unit, the smallest related family unit in Census terms, the subfamily. None of these additional changes (not shown) matter substantively.

Our final robustness check looks at effects of adding lags (one or two years) of the unemployment rate to our main specification (Appendix Table A7).47 Here, the cumulative effect is relatively unchanged, and the bulk of the effects are on the contemporaneous level of the unemployment rate. In sum, our main results are robust to alternative definitions for resources, poverty thresholds, the measure of the economic cycle, and the regression specification.

CONCLUSION

Beginning in 2007, the Great Recession led to unemployment rates unseen since the deep recessions of the early 1980s. At the same time, significant changes in the safety net occurred both before and during this most recent downturn. These two events make it important to explore the role of the safety net in providing protection during the Great Recession, both through the normal countercyclical response and through ARRA. We focus on child poverty, as children experience some of the highest poverty rates of any group in the United States.

We consider two child poverty measures, which differ in the way they count resources—one focuses on PI poverty and the other on ATT poverty. By comparing the response of these two poverty measures across the business cycle, we gain insight into the role played by the social safety net in protecting children's well-being against economic shocks. We use CPS data covering the period 2000 through 2014 and estimate state-year panel data models where we measure state business cycles using unemployment rates. Our results are identified using the significant and sizeable variation in the timing and severity of the business cycle across states.

We find that child poverty is cyclical and the cyclicality is larger in magnitude (in percentage terms) at lower points in the income-to-poverty ratio distribution. This finding has been shown in other work to be true historically and continues to be evident in the Great Recession. We also find that the safety net as a whole provides significant protection, as the cyclicality of ATT poverty is significantly lower than the cyclicality of PI poverty. While our main specifications rely on quasi-relative poverty thresholds as in the Historical SPM (Fox et al., 2015a), we find that the findings are quite robust across absolute measures such as the official poverty thresholds and anchored SPM thresholds (Wimer et al., 2014), and even when using the OECD's relative poverty threshold. Moreover, our results are robust to how we treat the value of health insurance and medical expenses when we calculate household resources, and to a variety of alternative model specifications. Lastly, while we find that on average the safety net is effective at mitigating the cyclicality of child poverty, our results also show that these effects are differential across groups and that cyclicality of poverty is larger for children in households headed by single parents, Hispanics, and, most significantly, immigrants or those with an immigrant spouse.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Patty Anderson, Chloe East, Kosali Simon, and George Saioc for generously sharing their expertise and data on state safety net policies and state policies regarding foreclosures, and Chris Wimer for sharing historical supplemental poverty thresholds from Fox et al. (2015a). Funding for the project was provided by UNICEF. Dorian Carloni and Krista Ruffini provided excellent research assistance.

APPENDIX

| Resource measures | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official poverty | SPM | Private income poverty | ATT poverty | Public assistance | Social insurance | |

| Private income | ||||||

| Wages and salaries | X | X | X | X | ||

| Self-employment income | X | X | X | X | ||

| Farm income | X | X | X | X | ||

| Returns from assets | X | X | X | X | ||

| Child support and alimony | X | X | X | X | ||

| Private disability and retirement | X | X | X | X | ||

| Value of employer contribution to HI | ||||||

| Transfers | ||||||

| AFDC/TANF | X | X | X | X | ||

| Social Security Ret./SSDI | X | X | X | X | ||

| SSI | X | X | X | X | ||

| Unemployment insurance | X | X | X | X | ||

| Food stamps | X | X | X | |||

| Free/reduced lunch | X | X | X | |||

| Housing subsidies | X | X | X | |||

| LIHEAP | X | X | X | |||

| Veterans payments, workers' comp. | X | X | X | X | ||

| Fungible value of Medicaid | ||||||

| Fungible value of Medicare | ||||||

| Taxes | ||||||

| EITC | X | X | X | |||

| Child Tax Credit | X | X | X | |||

| Additional Child Tax Credit | X | X | X | |||

| Stimulus Tax Credits/Rebates | X | X | X | |||

| Federal taxes, other | X | X | X | |||

| State taxes | X | X | X | |||

| FICA contributions | X | X | X | |||

| Deductions | ||||||

| Child Support | X | |||||

| Medical out-of-pocket expenditures | X | |||||

| Other work expenses | X | |||||

| Child care | X | |||||