College Enrollment and Completion Among Nationally Recognized High-Achieving Hispanic Students

Abstract

Hispanic high school graduates have lower college completion rates than academically similar white students. As Hispanic students have been theorized to be more constrained in the college search and selection process, one potential policy lever is to increase the set of colleges to which these students apply and attend. In this paper, we investigate the impacts of the College Board's National Hispanic Recognition Program (NHRP), which recognizes the highest-scoring 11th-grade Hispanic students on the PSAT/NMSQT, as a mechanism of improving college choice and completion. The program not only informs students about their relative ability, but it also enables colleges to identify, recruit, and offer enrollment incentives. Overall, we find that the program has strong effects on college attendance patterns, shifting students from two-year to four-year institutions, as well as to colleges that are out-of-state and public flagships, all areas where Hispanic attendance has lagged. NHRP shifts the geographic distribution of where students earn their degree, and increases overall bachelor's completion among Hispanic students who traditionally have had lower rates of success. These results demonstrate that college outreach can have significant impacts on the enrollment choices of Hispanic students and can serve as a policy lever for colleges looking to draw academically talented students.

INTRODUCTION

College completion among Hispanics remains persistently lower than both whites and other minority groups, even as their high school graduation and college attendance rates have risen over the past decade (Kena et al., 2015; Murnane, 2013). Improving degree completion for Hispanic students is particularly important as they are the largest minority group in the United States, increasing in population almost six-fold from 1970 to 2014 (Krogstad & Lopez, 2015). One potential method to increase degree completion is to expand the set of institutions to which Hispanic students apply and enroll, as the type of college attended has been shown to have causal impacts on degree attainment (Black & Smith, 2004; Cohodes & Goodman, 2014; Goodman, Hurwitz, & Smith, forthcoming; Smith, Pender, & Howell, 2013). This approach may be particularly relevant for Hispanic students, who have been identified as having relatively fewer educational opportunities in high school (Jackson, 2010; Kanno & Kangas, 2014), and may have stronger preferences for colleges close to home (Desmond & Turley, 2009; McDonough, 1999; Perna, 2000; Perna & Titus, 2005), which may restrict Hispanic students’ choice sets.

In this paper, we estimate whether the college application and enrollment decisions of high-achieving Hispanic students are impacted by the National Hispanic Recognition Program (NHRP), a College Board-created initiative that recognizes top-performing students based on their 11th-grade Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualify Test (PSAT/NMSQT, henceforth PSAT). We generate causal impacts using a regression discontinuity (RD) design that compares students who are barely eligible for this recognition to academically similar but unrecognized students just below the eligibility threshold. This program is similar in spirit to the National Merit Scholarship program, which was the focus of what is commonly credited as the first paper to employ an RD design (Thistlethwaite & Campbell, 1960).

NHRP status can impact students’ college-going decisions, and ultimately degree completion, through two primary mechanisms. First, research has shown that many high-performing students may not apply to the set of elite institutions where they are eligible, and that informational interventions can shift where students apply and ultimately enroll (Hoxby & Turner, 2013, 2015).1 NHRP students receive a clear and straightforward piece of information that identifies them as exceptional academic performers. This information is also delivered to the students’ high school counselors, who are encouraged to recognize these students for their efforts. The provision of relatively simplistic information on academic performance has produced mixed results on students’ educational outcomes, ranging from positive (e.g., Papay, Murnane, and Willett (2015)) to null (Foote, Schulkind, & Shapiro, 2015; Jackson, 2015). We do not find evidence that this aspect of the intervention—providing information to students on their relative academic ability—has any meaningful impact on academic preparation in high school, yet it does induce students in some regions of the country to target and attend more elite institutions, suggesting that low-cost provision of certain types of information to Hispanic students can potentially improve their transition into and through college.

The second mechanism that might impact college choice and completion comes in the form of targeted outreach and financial incentives from colleges that choose to actively recruit NHRP scholars. Increasing student body diversity, both racial and socioeconomic, remains a priority among many of the nation's colleges. Colleges are making costly efforts to increase application volume among underrepresented students, and about one-quarter of private nonprofit and public four-year institutions consider race when making admissions decisions, with higher rates among the most competitive college.2 Since the program's founding, NHRP has licensed lists of NHRP students to a small number of four-year colleges who have used this service for targeted outreach. We find that the NHRP recipients are 5 percentage points more likely to attend these recruiting institutions, a 16 percent increase above the baseline.

Overall, NHRP recipients are 1.5 percentage points more likely to enroll at a four-year institution. There are also significant effects on the type of four-year institution attended, as NHRP qualification increases attendance at out-of-state colleges and at public flagship institutions, by roughly 5 and 3 percentage points, respectively. We find that nearly all of the main effects documented in this paper are driven by students residing in the West and Southwest regions of the nation, which have the highest concentration of Hispanic students. In other geographic regions, we find no observable effects on college choice.

In addition to shifting where students enroll, NHRP also alters the geographic distribution of the bachelor's degrees earned, as recognized scholars are 3 percentage points more likely to earn their degree out-of-state. Overall effects on bachelor's degree completion are generally positive though statistically insignificant, but these relatively muted overall effects hide substantial cross-group differences. In particular, we find sizeable increases in bachelor's completion among students who otherwise were at the highest risk for dropping out, including students with the lowest SAT scores, those whose parents did not complete high school, and those attending high schools with the highest concentration of Hispanic students. Taken as a whole, this research demonstrates that high-achieving Hispanic students’ college choices can be influenced late in their high school careers and that with the proper information and incentives these students can be influenced to attend and graduate from colleges that they ordinarily might not have considered.

NATIONAL HISPANIC RECOGNITION PROGRAM

The NHRP was initiated in 1983 by the College Board, and identifies the top 2.5 percent of Hispanic scholars based on the 11th-grade PSAT. The PSAT is taken by over three million high school students per year, as both a practice exam for the SAT and as a means for qualification for the highly prestigious National Merit Scholarship program. For the students examined in the paper, the PSAT consisted of three sections: Math, Critical Reading, and Writing. Each section is scored from 20 to 80 points, producing a maximum score of 240. Each student receives a PSAT Score Report that contains feedback on their performance, including scale scores for each section and the number of questions answered correctly across a range of skills. Students are also provided with their national percentile rank, though this is in small text with language that suggests students can “compare your performance with college-bound juniors.”

In order to identify cutoffs for NHRP eligibility, the College Board rank orders PSAT performance among Hispanic scholars separately within each of six geographic regions that are associated with College Board regional offices. The award recognizes the top 2.5 percent within each region, which identifies approximately 5,000 NHRP scholars per year. As seen in Appendix Table A1, the Western and Southwestern regions contain almost 31 percent of all junior PSAT takers, but 60 percent of all Hispanic junior PSAT takers.3 Within these two regions, Texas and California contain almost 90 percent of all Hispanic PSAT takers.

To be eligible for NHRP, students must take the PSAT in October of their 11th grade year. NHRP eligibility cutoffs range from the low 180s to the mid-190s, depending on region and year, out of a possible 240 on the three-section exam. The Western and Southwestern regions typically have the lowest cutoffs.4 Initial notification of eligibility, based on administrative PSAT scores, arrives in February or March. In order to qualify, the self-identified Hispanic students must first verify that they are one-quarter Hispanic and the high school must document that their junior year cumulative GPA is 3.5 or above by June 15.5 In practice, we find that almost all self-identified Hispanic students above the PSAT cutoff are able to satisfy both the ethnic and GPA requirements.6 Although the NHRP cutoff represents the top 2.5 percent of Hispanic PSAT takers, the eligibility cutoff lies somewhere between the 85th and 95th percentile in the national distribution during 2007 to 2009, depending on the year and region.

The NHRP does not provide any direct financial reward to students, but does provide them with a number of signals that might impact their subsequent college preparation during their senior year. The College Board sends a letter directly to students that congratulates them and invites them to participate in the program and, conditional on earning the award, encourages them to use the recognition on college, scholarship, internship, and job applications. School counselors are contacted to help students complete the necessary paperwork, counseled to encourage these students to apply to top universities, and asked to honor these awardees through some type of school recognition. Finally, by notifying Hispanic students that they are academically in the top 2.5 percent of ethnically similar students nationwide, NHRP provides an additional, perhaps surprising, recognition of academic ability.

The last relevant detail that is made salient to students is that the College Board shares NHRP data with a set of four-year postsecondary institutions that are interested in communicating with academically exceptional Hispanic/Latino students. We have data for the set of recruiting institutions for three high school graduating cohorts: 2007, 2008, and 2009. There are approximately 200 institutions that license the list per year, though 323 unique institutions appear across three years combined. The first two sets of columns in Appendix Table A2 compare recruiting institutions to the full set of non-recruiting four-year institutions that are attended by at least one Hispanic student within 15 points of the eligibility threshold. Recruiting institutions are, on average, of higher quality, as measured by their Barron's ranking, graduation rate, and average SAT scores.7 Recruiting institutions are also slightly larger and more expensive, though percentages of enrolled students identifying as Hispanic are comparable between these two types of colleges. These recruiting institutions were also popular among Hispanic students, as at least one student within 15 points of the NHRP threshold attended 88 percent (293 of 323) of the recruiting institutions. The last column of Appendix Table A2 describes seven recruiting institutions that we refer to as “core” recruiting institutions, which are discussed in more detail later in the paper. These seven institutions are shown to be particularly attractive to NHRP scholars, and we create a distinct label simply to facilitate our discussion of these universities.

For recruiting colleges, the benefit of this list is that it provides an easy opportunity to engage in direct outreach to high-performing Hispanic students. In addition, a number of these schools offer financial awards to NHRP scholars, which range from relatively modest sums to, in some cases, four years of full tuition plus an annual stipend. Some colleges make these awards conditional on available resources or other requirements, such as minimum SAT or ACT scores.

DATA

We first construct a national sample of all Hispanic 11th-grade PSAT takers from the graduating high school cohorts of 2004 to 2010, removing students residing in U.S. territories or abroad. (We use a similar sample of non-Hispanic students as both a comparison group for understanding characteristics of high-performing Hispanic students and as a robustness check for causal estimates of the program). We link these individual-level records to a number of auxiliary data sources. The first are records on all College Board related activities, which include an individual's history of SAT attempts, the institutions to which they sent their SAT scores (Score Sends), and any Advanced Placement (AP) test-taking, along with high school attended and basic demographics. The second source of data is the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). As of 2015, over 3,600 postsecondary institutions participate in NSC, which collects postsecondary enrollment information on most students enrolled in public and private colleges within the United States. Our NSC match allows us to track the high school graduating classes of 2004 through 2008 for six years, with the classes of 2009 and 2010 tracked for five and four years, respectively. The third matched data sources are the Common Core of Data (CCD) and Private School Survey (PSS) from the National Center for Education Statistics, which contains information about school size, demographics, and geographic location. These data are linked to the high school attended when each student took the PSAT.8 The fourth data source includes characteristics of the postsecondary institutions, derived from Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), and linked to the initial postsecondary institution attended by sampled students.

The final data source contains the official list of NHRP scholars and recruiting institutions. These data are only available for the high school graduating cohorts of 2007 through 2009, and we match the list of NHRP scholars to College Board records to identify the region-specific NHRP cutoffs in each of those three years. In addition, we can reconstruct eligibility cutoffs for four additional high school graduating cohorts—2004, 2005, 2006, and 2010—provided we restrict our analyses only to students from the two largest regions, the West and Southwest. Although we can only reconstruct cutoffs for two of the six regions, combined they account for approximately 60 percent of all NHRP scholars in a given year.

Throughout the paper, we present results based on the full sample of Hispanic students graduating high school from 2004 through 2010. We choose this approach as the estimates are more precise than in our three-year sample, which is particularly important for interpreting impacts on degree completion or heterogeneous effects based on region or family background. We later show that none of the main results are altered when we focus only on the cohorts of 2007 through 2009.

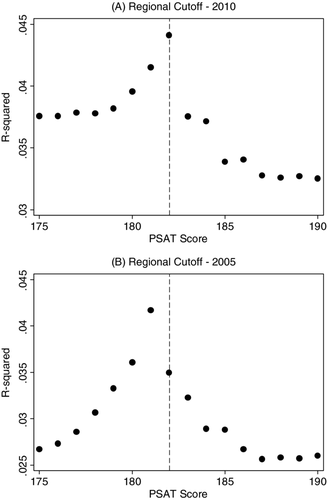

Our methodology for constructing the full sample is as follows. As we will show, NHRP eligibility induces a large shift in students choosing to attend college out-of-state at seven specific institutions, all located outside of Texas and California.9 Using the Texas and California samples, we fit simple RD specifications at placebo thresholds within 10 points of the 2007 discontinuities, select the threshold with the highest R2, and apply this value to all states within the appropriate region. We are able to verify the accuracy of this methodology in the Western and Southwestern regions by re-identifying the cutoffs in the three years for which we have available data.10 In the other four regions we were generally unable to re-identify the known cutoffs in 2007 through 2009 using this approach, and so they are omitted.11

ESTIMATION STRATEGY

Our focus in equation 1 is the intent-to-treat parameter,, which identifies the causal impact of the program. Specifically, β2 is the magnitude of the difference between recognized and non-recognized scholars, though we can only interpret our estimate as local to students in the vicinity of the threshold. As stated above, we present reduced-form results that are based on eligibility for NHRP status, rather than results based on actual NHRP recognition, as almost all eligible students indeed qualified for the program. Our preferred approach to estimating β2 is to fit regressions with linear slopes that are allowed to vary on either side of the cutoff, over a 15-point bandwidth and using rectangular kernels, though all results are robust to alternate estimation strategies, as we show in Appendix Table A3.12 Bandwidth selection was determined by the IK and CCT optimal bandwidth calculations, which consistently suggested bandwidths between 15 and 20 points.13 Although it is common practice to cluster standard errors by the running variable when it is discrete (Lee & Card, 2008), we find that robust standard errors are generally larger than clustered standard errors and thus more conservative, and we present these throughout.

There are strong theoretical reasons for the validity of the empirical strategy. The cutoffs vary by year and are unknown ex ante, and students only have one opportunity to take the test in their junior year, the only year in which the PSAT contributes to NHRP recognition, which prevents any gaming related to exam re-taking. We also present empirical results below that suggest there is no evidence of manipulation that might invalidate our results.

RESULTS

Characteristics of High-Performing Hispanic Students

As stated above, PSAT scores range from 60 to 240, and NHRP eligibility cutoffs range from the low 180s to the mid-190s, depending on year and region. Restricting to students within a 15-point bandwidth of the NHRP cutoff produces a data set of approximately 58,000 students combined across all years, or 33,000 students when restricting to only the 2007 through 2009 cohorts for which we have exact information on recruiting institutions and scholar recipients. Summary statistics for these two groups are presented in the first two columns of Table 1. The third set of columns presents summary statistics for white students with PSAT scores within the same bandwidth as our high-performing Hispanic students sample; for ease of comparability to the national sample, we focus on 2007 through 2009. The fourth set of columns provides summary statistics for an alternate sample of what we define as “low-performing” Hispanic students. Specifically, this group includes all students scoring between 70 to 90 PSAT points below the NHRP cutoff, which corresponds to the 25th percentile Hispanic student, on average.

| High-performing Hispanic | High-performing Hispanic | High-performing white | Low-performing Hispanic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years | 2007 to 2009 | 2007 to 2009 | 2007 to 2009 | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Female | 50.6% | 0.50 | 50.8% | 0.50 | 51.2% | 0.50 | 56.8% | 0.50 |

| No CCD data | 23.4% | 0.42 | 25.0% | 0.43 | 28.3% | 0.45 | 10.9% | 0.31 |

| Location: City | 33.8% | 0.47 | 30.8% | 0.46 | 18.0% | 0.38 | 48.8% | 0.50 |

| Location: Suburb | 29.5% | 0.46 | 30.4% | 0.46 | 35.6% | 0.48 | 26.0% | 0.44 |

| Location: Town/rural | 13.9% | 0.35 | 14.4% | 0.35 | 23.0% | 0.42 | 16.5% | 0.37 |

| High school size | 2,057 | 930 | 2,030 | 945 | 1,611 | 808 | 1,900 | 1,053 |

| High school percent free/reduced-price lunch | 32.3% | 0.23 | 30.7% | 0.22 | 19.0% | 0.16 | 53.4% | 0.25 |

| High school Hispanic concentration | 35.1% | 0.29 | 31.8% | 0.28 | 8.5% | 0.11 | 52.7% | 0.31 |

| Only students below cutoff | ||||||||

| Parent education less than high school | 19.6% | 0.40 | 17.8% | 0.38 | 4.3% | 0.20 | 44.4% | 0.50 |

| Income less than $50,000 | 31.4% | 0.46 | 28.3% | 0.45 | 8.4% | 0.28 | 45.1% | 0.50 |

| Number of AP exams taken | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| Number of AP exams passed | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 8.6 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Took SAT | 85.7% | 0.35 | 85.8% | 0.35 | 78.0% | 0.41 | 40.8% | 0.49 |

| Attended two-year college | 14.3% | 0.35 | 12.8% | 0.33 | 8.2% | 0.27 | 42.7% | 0.49 |

| Attended four-year college | 78.5% | 0.41 | 80.4% | 0.40 | 86.4% | 0.34 | 19.3% | 0.39 |

| Attended out-of-state college | 21.4% | 0.41 | 24.9% | 0.43 | 32.9% | 0.47 | 5.3% | 0.22 |

| Attended Barron's Most Competitive | 15.4% | 0.36 | 18.1% | 0.39 | 10.0% | 0.30 | 0.1% | 0.03 |

| Attended Barron's Most/Highly Competitive | 52.4% | 0.50 | 56.5% | 0.50 | 61.0% | 0.49 | 2.5% | 0.16 |

| Average SAT of college | 1174 | 138 | 1186 | 138 | 1174 | 109 | 994 | 97 |

| Four-year bachelor degree completion | 40.6% | 0.49 | 43.9% | 0.50 | 56.1% | 0.50 | 2.9% | 0.17 |

| Six-year bachelor degree completion | 60.8% | 0.49 | 63.9% | 0.48 | 76.0% | 0.43 | 8.5% | 0.28 |

| Only students below cutoff who took SAT | ||||||||

| Maximum SAT score | 1210 | 92 | 1220 | 93 | 1247 | 86 | 760 | 102 |

| Number of score sends | 5.5 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Score send: Average SAT | 1211 | 101 | 1218 | 102 | 1198 | 92 | 1070 | 92 |

| Score send: Maximum SAT | 1340 | 130 | 1347 | 127 | 1308 | 119 | 1174 | 138 |

| Applied to Barron's Most Competitive | 58.9% | 0.49 | 61.9% | 0.49 | 45.9% | 0.50 | 13.5% | 0.34 |

| Applied to Barron's Most/Highly Competitive | 85.8% | 0.35 | 86.5% | 0.34 | 80.1% | 0.40 | 41.4% | 0.49 |

| Sent score to out-of-state college | 56.8% | 0.50 | 61.1% | 0.49 | 63.5% | 0.48 | 17.3% | 0.38 |

| N | 57,722 | 33,277 | 497,317 | 147,794 | ||||

- Notes: High-performing Hispanic students includes all students within 15 points of NHRP eligibility threshold. Low-performing identifies students 70 to 90 PSAT points below the threshold. Variables that might be impacted by NHRP recognition, including data collected from College Board forms that only occur after the PSAT is taken, only focus on control students below the NHRP eligibility threshold.

Although previous research on NHRP scholars describes them as having somewhat similar educational backgrounds to similarly performing white peers (Clewell & Joy, 1988), our results suggest a number of key differences between these groups. Hispanic students are more likely to live in cities rather than in suburbs or more rural areas, and attend larger high schools with significantly more low-income and Hispanic students. They are also about four times as likely to be in families with incomes below $50,000 or to have parents who did not graduate from high school. Compared to similarly achieving White students, sampled Hispanic students have taken and passed fewer AP exams by the time they graduate from high school. Attending an out-of-state or private college is generally more expensive than attending an in-state alternative, due to tuition, room and board, and transportation costs. Each of these differences may help contribute to the lower attendance at four-year, private, or out-of-state colleges also seen in Table 1.

High-performing Hispanic students are actually more likely to attend selective institutions than their white peers, and are almost twice as likely (18 percent compared to 10 percent) to attend a college classified as Most Competitive by Barron's, the highest possible ranking. Although their SAT scores are slightly lower than their white peers, they send their SAT scores to institutions with higher average SAT scores of enrolled students.14 Perhaps surprisingly, high-performing Hispanic students are almost equally likely to send their SAT scores out-of-state (61 percent compared to 64 percent among high-achieving White students), implying that Hispanic students are, in fact, considering colleges far-from-home at the outset of their college searches.

We also compare high-performing and low-performing Hispanic students to better understand differences between these two populations. In most ways these differences mirror differences between high-performing Hispanic and white students, with low-performing Hispanic students again more likely to live in cities, attend high schools with high concentrations of low-income and Hispanic students, and come from families with lower incomes and educational attainment. We also estimate that the rate of non-public high school attendance is higher for high-performing than for low-performing Hispanic students (25 percent compared to 11 percent).

Geographically, the maps in Figure 1 show the concentration of NHRP students from the 2007 to 2009 cohorts, for whom we have national coverage, and the fraction of all students that meet the NHRP guidelines. As the first map shows, NHRP recipients are primarily concentrated in Southern California; the Atlantic coast of Florida; metro New York; and the greater metropolitan areas of Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix. In fact, just 25 U.S. counties were home to nearly half of the NHRP scholars between 2007 and 2009. Despite the tendency of NHRP scholars to reside in urban centers, there are also fairly rural areas that boast large numbers of NHRP scholars, such as the Rio Grande Valley of Texas and Eastern Washington. Compared to their more urban counterparts, high-achieving students in rural areas may not have the knowledge or support systems to navigate the college application process and they likely have limited contact with colleges, potentially making direct outreach to these individuals particularly impactful.

From the perspective of colleges, efficient recruiting might entail a targeting of the geographic regions with the highest density of high-achieving students. The second panel of Figure 1 shows that high-achieving counties are fairly dispersed across the nation with zones of higher achievement similar to those identified by Hoxby and Avery (2013), traversing a central belt near the Mississippi river and also the Boston through Washington megalopolis. While some geographic regions, such as the New York metro, contain large numbers of Hispanic scholars and also have high concentrations of high-achieving students, other areas with large numbers of NHRP scholars such as the Rio Grande Valley are among the lowest in the nation in terms of density of high achieving-students. Overall, we find that high-achieving Hispanic students are somewhat more geographically dispersed compared to the typical high-achieving student. If we rank the highest-achieving counties in the United States by the fraction of junior PSAT test-takers of any race/ethnicity who met the high PSAT benchmarks for NHRP, we find that the top decile of U.S. counties contain 45 percent of students across the nation meeting these benchmarks. However, these highest-achieving U.S. counties only contain 36 percent of Hispanic students who meet the NHRP benchmarks, suggesting that, in comparison to the typical high-achieving student, Hispanic high achievers tend to be scattered in lower-achieving counties.

Validity of Research Design

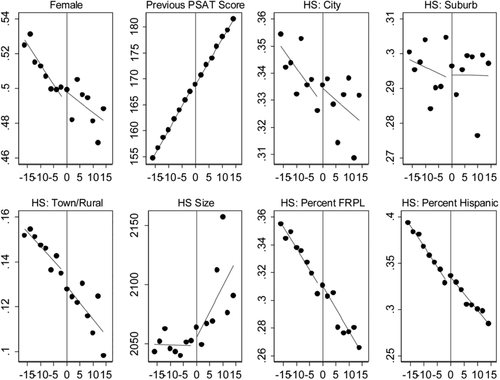

Although the theoretical foundation for our research design is strong, we test whether there is the appearance of manipulation near the threshold that would render our analyses invalid. First, we look for evidence of bunching of observations near the threshold that might suggest students can manipulate treatment assignment. Figure 2 provides a plot of the density of observations near the centered cutoff score. Visually, there is no evidence of manipulation or a jump in any of the bins at any point in the distribution. (This figure also makes clear that extending bandwidths beyond 20 points provides little benefit, as there are few treatment students who score at this level.) The second RD requirement is that all other covariates that may be related to potential outcomes are smooth in the vicinity of the threshold. To test this assumption, we fit a series of regression models similar to that of equation 1 above, but placing our covariates on the left-hand side of the equation. If the NHRP threshold is exogenously defined we should see no evidence of breaks in continuity, meaning that our estimate of β2 should be null. We provide these results in Table 2 for a variety of characteristics, and see no evidence of manipulation related to sex, subgroups of Hispanic ethnicity, previous PSAT scores, or other high school characteristics based on CCD data. Graphical results for covariate balance are shown in Figure 3.

| Effect | Control mean | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.010 | 50.5% |

| (0.009) | ||

| Mexican American | 0.003 | 49.2% |

| (0.008) | ||

| Puerto Rican | –0.000 | 6.5% |

| (0.004) | ||

| Other Hispanic | –0.003 | 44.3% |

| (0.008) | ||

| Previously took PSAT | 0.007 | 66.4% |

| (0.008) | ||

| Previous PSAT score | –0.477+ | 167.9 |

| (0.244) | ||

| Location: City | –0.003 | 47.3% |

| (0.008) | ||

| Location: Suburb | 0.008 | 40.2% |

| (0.008) | ||

| Location: Town/rural | –0.005 | 17.1% |

| (0.006) | ||

| High school size | –1.880 | 1,870 |

| (17.282) | ||

| High school percent free/reduced-price lunch | 0.003 | 29.8% |

| (0.004) | ||

| High school Hispanic concentration | 0.006 | 32.1% |

| (0.005) | ||

| N | 57,722 | |

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state-by-year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Sample sizes for high school characteristics are slightly smaller than the full sample due to unmatched or missing data.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

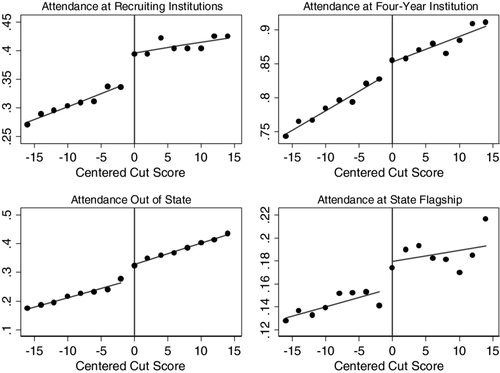

Enrollment Results—National Sample

Table 3 provides the results on the impact of NHRP on college attendance patterns across all regions for the 2004 to 2010 high school graduating cohorts, focusing on the initial institution attended. The first column shows that NHRP dramatically alters college attendance patterns, as students are 5 percentage points (almost 16 percent) more likely to attend NHRP recruiting colleges, and almost 6 percentage points more likely to attend the seven core recruiting institutions, described below.15 This shifting influences the sector of college attendance, as students are approximately 1.5 percentage points more likely to enroll at a four-year institution, with about two-thirds of this effect driven by movement away from the two-year sector. There are also significant effects on the type of four-year institution attended, as NHRP qualification increases attendance at out-of-state and at state flagship institutions by roughly 5 and 3 percentage points, respectively. These results are shown graphically in Appendix Figure A1. Estimates using triangular kernels, alternate bandwidths, covariates, or clustered standard errors are presented in Appendix Table A3 and produce nearly identical results, with estimates rarely changing by more than a few tenths of a percentage point across specifications.16

| All colleges | Recruiting colleges | Non-recruiting colleges | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | |

| College sector | ||||||

| Attend college | 0.005 | 93.4% | ||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Two-year college | –0.010+ | 10.1% | ||||

| (0.005) | ||||||

| Recruiting institution | 0.053** | 33.8% | ||||

| (0.008) | ||||||

| Core seven recruiting institution | 0.058** | 4.1% | ||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| Other non-core recruiting institutions | –0.005 | 29.6% | ||||

| (0.008) | ||||||

| Four-year college | 0.015* | 83.3% | 0.053** | 33.8% | –0.038** | 49.5% |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.008) | ||||

| Out-of-state college | 0.047** | 29.2% | 0.058** | 10.0% | –0.011+ | 19.2% |

| (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.006) | ||||

| Flagship | 0.029** | 14.9% | 0.028** | 8.1% | 0.001 | 6.8% |

| (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.004) | ||||

| Private | –0.002 | 35.0% | 0.003 | 12.2% | –0.005 | 22.8% |

| (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.007) | ||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.005 | 23.0% | –0.001 | 6.8% | 0.006 | 16.2% |

| (0.007) | (0.004) | (0.006) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | –0.005 | 19.8% | 0.002 | 12.0% | –0.007 | 7.8% |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.004) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | –0.001 | 18.0% | 0.013** | 6.5% | –0.014** | 11.6% |

| (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.005) | ||||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.016* | 22.4% | 0.039** | 8.6% | –0.023** | 13.8% |

| (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.006) | ||||

| N | 57,722 | 57,722 | 57,722 | |||

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

We find no detectable impacts on attendance at private institutions or at the Most Competitive Barron's institutions. Instead, the impacts seem to be driven by attendance at less selective colleges that we label “Less Competitive”; these include all four-year schools that rank below Barron's Most or Highly Competitive categories or have no Barron's ranking. Other than inducing students to travel farther from home, there are no statistically significant aggregate impacts on most relevant college characteristics, including average SAT, graduation rate in 150 percent time (four-year colleges only), expenditures per FTE, or sticker price tuition. (We omit these results here for brevity, but discuss them in more detail when we discuss regional variation in Table 5).17

The third through sixth columns of Table 3 attempt to distinguish the contributions of recruiting and non-recruiting institutions to the observed college choice shifts. In the third column we estimate impacts on the full sample using the same set of outcomes as column 1, but interact the outcome variables with a dummy for recruiting schools. We then implement the same approach in the fifth column, with separate regressions that interact the outcome with a dummy for non-recruiting institutions. The sum of the coefficients in columns 3 and 5 is equivalent to the corresponding coefficients in column 1.

Although the NHRP increased overall four-year college enrollment by 1.5 percentage points, there was a substantial shifting of students within the four-year sector. Students are 5.3 percentage points more likely to attend recruiting institutions and 3.8 percentage points less likely to attend non-recruiting four-year institutions. Students are almost 6 percentage points more likely to attend NHRP recruiting institutions out-of-state, and these recruiting colleges actually tend to draw high-performing Hispanic scholars away from both in-state and alternative out-of-state colleges.

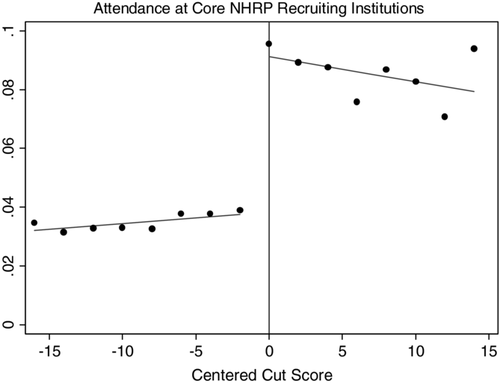

Further investigation reveals that the seven core institutions, previously described in Appendix Table A2, account for virtually all of the shifting toward NHRP recruiting institutions.18 NHRP scholars were 5.8 percentage points more likely to attend these colleges (Appendix Figure A2); given the baseline value of 4.1 percentage points, this means students were about 140 percent more likely to attend one of these seven core recruiting institutions as a result of the program. Although we cannot identify these schools by name, we can provide a few key details, which are also included in Appendix Table A2. All seven are large, public institutions located outside of California and Texas, the two states that contribute the highest number of NHRP scholars. Whereas the full list of recruiting institutions contains a number of private and Most Competitive Barron's ranked schools, three of the seven are listed as Barron's Highly Competitive, and the remaining four as Less Competitive. Four serve as state flagships, even though flagships make up only a small portion of the full set of recruiting institutions. Although there is no exhaustive list of the methods by which recruiting institutions engage students, all seven institutions offer substantial financial aid for NHRP scholars, and this information is easily available on these colleges’ websites. Five of the seven institutions currently offer students a full four years of out-of-state tuition, with some including additional cash scholarships. Nonetheless, there are other recruiting institutions that are known to offer financial awards that do not draw students in similar numbers, suggesting that financial aid appears to be a necessary but not sufficient condition for enrolling these scholars.

Given that students shift almost completely toward recruiting institutions, the primary mechanism appears to be a combination of direct college outreach and financial aid. An alternate, or perhaps complementary, mechanism is that NHRP induces students to improve their academic preparation in high school, making them more attractive candidates to these colleges. We investigate this possibility in Table 4. We find no evidence that NHRP scholars improve their academic performance, as measured by participation and performance in other College Board services. NHRP recognized scholars do not take or pass more AP exams, score higher on the SAT, or re-take the SAT more often. We find similarly null results when we examine other possible SAT outcomes, such as initial score or total score on the 2400 point scale, but omit these results for brevity. There is evidence that students alter their behavior by sending SAT scores to more institutions, confirming that NHRP induces students to target and attend schools that were previously outside of their college choice set. Of course, we cannot rule out unobserved changes in student preparation, such as improvements in GPA, changes in course transcripts that do not impact AP taking, or participation in extra-curricular activities that might make a student more attractive.

| Effect | Control mean | |

|---|---|---|

| AP exams taken in 12th grade | 0.042 | 1.97 |

| (0.030) | ||

| AP exams passed in 12th grade | 0.024 | 1.41 |

| (0.025) | ||

| SAT | ||

| Took SAT | 0.007 | 87.6% |

| (0.005) | ||

| Maximum score (1600 point scale) | –0.832 | 1264 |

| (1.492) | ||

| Total SAT attempts | 0.005 | 1.83 |

| (0.013) | ||

| Score sends | ||

| Total | 0.207** | 6.76 |

| (0.071) | ||

| College SAT: Average | –1.413 | 1239 |

| (1.851) | ||

| College SAT: Minimum | –4.318* | 1099 |

| (2.077) | ||

| College SAT: Maximum | 2.464 | 1369 |

| (2.308) | ||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.064 | 2.40 |

| (0.050) | ||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | 0.024 | 1.41 |

| (0.025) | ||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 0.037 | 1.24 |

| (0.024) | ||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.131** | 0.97 |

| (0.024) | ||

| N | 57,722 | |

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

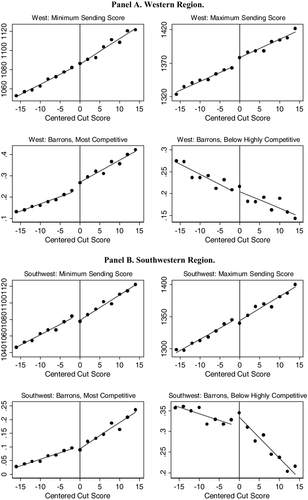

Regional Variation in NHRP Impacts

Given the national sample of Hispanic scholars and variation in high school environments, college quality, state policies, and proximity of recruiting colleges, we should expect a range of responses to the NHRP award, depending on where students reside. We find strong regional differences in the effect of NHRP status, with students in the Western and Southwestern regions entirely driving the results documented above (Table 5, columns 1 and 3). There are almost no impacts on attendance patterns for students in the other four regions, with the exception of a 2.4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of attending one of the seven core recruiting institutions (Table 5, column 5), over a base of 0.2 percent, which indicates the strong effects of the recruitment even in the presence of distance. The general lack of results is not simply due to statistical power, as the coefficients are much smaller than for the other regions. We reserve a discussion of why we see weaker effects in these regions for the conclusion.

| West region | Southwest region | All other regions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | |

| Score sends | ||||||

| Total | 0.302* | 7.3 | 0.059 | 5.8 | 0.285+ | 7.2 |

| (0.118) | (0.104) | (0.156) | ||||

| College SAT: Minimum | –0.760 | 1090 | –7.389* | 1086 | –5.706 | 1132 |

| (3.178) | (3.426) | (4.538) | ||||

| College SAT: Maximum | 8.945* | 1370 | –7.512+ | 1346 | 6.924+ | 1397 |

| (3.683) | (4.102) | (4.044) | ||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.139+ | 2.7 | –0.086 | 1.6 | 0.160 | 3.0 |

| (0.083) | (0.069) | (0.121) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | 0.060 | 1.2 | –0.014 | 1.5 | 0.029 | 1.6 |

| (0.037) | (0.039) | (0.060) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 0.074+ | 1.6 | 0.042 | 1.0 | –0.026 | 1.1 |

| (0.044) | (0.035) | (0.045) | ||||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.092* | 1.0 | 0.217** | 1.1 | 0.061 | 0.8 |

| (0.040) | (0.041) | (0.045) | ||||

| College sector | ||||||

| Two-year college | –0.020* | 14.0% | –0.001 | 9.6% | –0.009 | 4.7% |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.007) | ||||

| Four-year college | 0.019+ | 80.3% | 0.013 | 83.9% | 0.013 | 87.1% |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | ||||

| Recruiting institution | 0.054** | 25.0% | 0.075** | 47.0% | 0.017 | 28.7% |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.016) | ||||

| Core seven recruiting institution | 0.044** | 6.5% | 0.094** | 4.3% | 0.024** | 0.2% |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.005) | ||||

| Other non-core recruiting institution | –0.035** | 55.3% | –0.062** | 36.9% | –0.003 | 58.4% |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.017) | ||||

| Out-of-state college | 0.049** | 27.1% | 0.069** | 22.0% | 0.008 | 43.1% |

| (0.012) | (0.012) | (0.017) | ||||

| Flagship | 0.024** | 12.0% | 0.039** | 16.0% | 0.024+ | 18.0% |

| (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.014) | ||||

| Private | 0.026* | 32.9% | –0.040** | 27.7% | 0.012 | 49.1% |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.017) | ||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.030* | 24.9% | –0.012 | 10.6% | –0.012 | 38.0% |

| (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.017) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | –0.002 | 12.1% | –0.013 | 27.5% | 0.005 | 21.1% |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.015) | ||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | –0.014 | 23.9% | 0.007 | 12.9% | 0.012 | 16.0% |

| (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.013) | ||||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.006 | 19.4% | 0.031* | 32.8% | 0.008 | 12.0% |

| (0.011) | (0.013) | (0.012) | ||||

| College characteristics (IPEDS) | ||||||

| Mean SAT | 6.762 | 1211 | –4.315 | 1155 | –2.287 | 1262 |

| (4.218) | (4.297) | (4.921) | ||||

| Graduation rate in 150% time | 0.412 | 73.4 | –0.011 | 61.8 | –0.712 | 77.3 |

| (0.490) | (0.625) | (0.592) | ||||

| Expenditures per FTE | 3,429.375* | $40,478 | –5,302.866** | $41,993 | 90.125 | $30,411 |

| (1,658.354) | (1,734.603) | (988.301) | ||||

| Tuition | 900.172* | $15,150 | –1,437.762** | $13,645 | –192.834 | $22,003 |

| (394.313) | (362.955) | (521.801) | ||||

| Percentage Hispanic | –0.008** | 15.0% | –0.010 | 22.7% | –0.005 | 9.9% |

| (0.003) | (0.006) | (0.004) | ||||

| Range of NHRP cut scores | 183 to 185 | 179 to 183 | 184 to 195 | |||

| N | 22,921 | 21,605 | 13,196 | |||

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

Focusing on the two heavily Hispanic West and Southwest regions, we observe significant differences in student responses to the NHRP at the college application stage. Students from the West appear to have increased the academic range of colleges in their application set, with more total score sends and an emphasis on reach colleges, whereas Southwest students do not alter their total score sends but shift their interest toward institutions with weaker peers (see Table 5 and Appendix Figure A3).19 For example, across all colleges to which students sent SAT scores in the West, the NHRP induced students to upwardly adjust their highest reach college by 9 SAT points on the 1600 (math + critical reading) scale, while students from the Southwest downwardly adjusted their highest reach by 7 SAT points. Students from the West sent more scores to colleges in the Most Competitive category as well as to colleges in the Less Competitive category as a result of NHRP. In the Southwest, the NHRP induced students to primarily send more SAT scores to colleges in the Less Competitive category.

Differences in score send patterns are reflected in subsequent enrollment decisions, with students from the West more likely to shift into colleges with academically stronger students, higher educational expenditures per FTE student, and fewer enrolled Hispanics. For example, Table 5 shows that students from the West are 3 percentage points more likely to attend private and Barron's Most Competitive colleges, with no significant increase in enrollment at Less Competitive colleges. In the Southwest, we find evidence of a decline in these measures as a result of the NHRP, as students are 4 percentage points less likely to attend private colleges and 3 percentage points more likely to enroll at Less Competitive colleges. Despite these differences, students increase enrollment at the seven core institutions in both regions, by almost 5 and 10 percentage points in the West and Southwest, respectively.

NHRP impacts across regions are similar when using only the 2007 through 2009 cohorts, as shown in Appendix Table A4.20 For students in the Southwest, all results in the three-year sample retain their statistical significance, at least at the 10 percent level, and a few select results, such as impacts on the minimum and maximum SAT values for student score sends, appear slightly larger in magnitude. In the West region, the primary results on sending scores to Barron's Less Competitive schools, along with attendance at out-of-state, flagship, and recruiting institutions, all retain their statistical significance. Other West results are slightly less consistent, though this is primarily due to changes in precision rather than coefficient estimate. For example, impacts on total score sends, private school attendance, and average tuition of attending institution are all similar in magnitude but lose their significance in the smaller sample. A small number of results are smaller in magnitude, but in no case do the estimates switch signs or can we reject that they are statistically different from the full sample.

Completion Results

In Table 6 we investigate whether the NHRP impacts the likelihood that students earn a bachelor's (B.A.) degree within four years. Our overall results are positive though statistically insignificant, with NHRP increasing B.A. completion by 1.3 percentage points. Perhaps surprisingly, given the cross-regional differences in enrollment patterns, the B.A. increase is relatively equal across regions, measuring 1.1, 1.4, and 1.6 percentage points in the West, Southwest, and other regions, respectively. As four-year degree completion effects may reflect changes in time-to-degree, rather than whether a student ultimately receives a bachelor's degree, we have generated six-year bachelor's completion parameter estimates using the 2004 to 2008 cohorts. We provide these results in Appendix Table A5.21 Other than decreased precision due to the smaller sample, the results are generally similar to those for four-year completion rates, with no significant differences. These positive but imprecisely estimated completion impacts suggest that high-performing Hispanic students are not harmed by enrolling at colleges that they may not have ordinarily considered. Our ability to detect impacts of NHRP on bachelor's degree completion is limited by the number of students whose actual college choices are affected by the recognition program. Results on college-going and college-choice suggest that relatively few students are altering enrollment decisions as a result of NHRP, and that many students are shifting between institutions with comparable completion rates. Nevertheless, there exists room for improvement on this metric as even among high-performing Hispanic students, the four- and six-year graduation rates for non-recognized control students at the threshold are 46 and 66 percent, respectively.

| All regions | West region | Southwest region | All other regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | Effect | Control mean | |

| All students | 0.013 | 45.7% | 0.011 | 45.3% | 0.014 | 38.6% | 0.016 | 56.7% |

| (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.018) | |||||

| Recruiting institution | 0.040** | 16.8% | 0.037** | 13.2% | 0.055** | 20.1% | 0.020 | 18.0% |

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.014) | |||||

| Core seven recruiting institution | 0.033** | 1.3% | 0.029** | 2.3% | 0.049** | 0.9% | 0.013** | 0.0% |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |||||

| Other non-core recruiting institution | –0.026** | 28.8% | –0.026* | 32.0% | –0.041** | 18.5% | –0.003 | 38.7% |

| (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.010) | (0.017) | |||||

| Out-of-state college | 0.028** | 18.1% | 0.038** | 16.8% | 0.033** | 12.5% | 0.003 | 28.7% |

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.016) | |||||

| In-state college | –0.014+ | 27.5% | –0.027* | 28.5% | –0.018 | 26.1% | 0.013 | 28.0% |

| (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.016) | |||||

| Mean SAT of college | –3.893 | 1243 | 2.768 | 1245 | –9.996 | 1197 | –5.698 | 1285 |

| (3.385) | (5.385) | (6.403) | (5.809) | |||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.001 | 16.5% | 0.017 | 16.4% | –0.011 | 8.5% | –0.008 | 28.4% |

| (0.006) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.016) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | –0.000 | 11.2% | –0.001 | 7.7% | –0.002 | 13.4% | 0.005 | 13.6% |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.012) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 0.001 | 9.2% | –0.012 | 13.2% | 0.007 | 5.2% | 0.016 | 8.7% |

| (0.005) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.010) | |||||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.012* | 7.7% | 0.009 | 6.5% | 0.021* | 10.8% | 0.006 | 5.3% |

| (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |||||

| N | 57,722 | 22,921 | 21,605 | 13,196 | ||||

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. Robust standard are errors in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

The fairly small changes in bachelor's completion impacts conceal much larger changes in where recipients earned their bachelor's degrees. The fraction of students earning bachelor's degrees in four years at recruiting institutions increased by 4 percentage points and at the seven core recruiting institutions by 3.3 percentage points. Moreover, the NHRP increases the share of students who earn bachelor's degrees out-of-state by 2.8 percentage points, or 16 percent, suggesting that the NHRP serves as a lever to geographically disperse high-achieving Hispanic students. Considered together with the college enrollment parameters in Tables 3 and 5, the completion point estimates in Table 6, reveal that induced students are succeeding at the colleges they would not ordinarily have attended. For example, we show that the NHRP increases out-of-state college enrollment by 4.7 percentage points (Table 3). Considered together with the increase in out-of-state bachelor's completion (2.8 percentage points), we estimate that nearly 60 percent of Hispanic students induced to attend out-of-state colleges ultimately earned bachelor's degrees in four years. When the time frame is extended to six years the percentage jumps to nearly 80 percent. This evidence casts doubt on the prevailing sentiment that high-performing Hispanic students may struggle to flourish in unfamiliar or uncomfortable postsecondary environments, or when separated from immediate family structures.

Table 6 also suggests potential changes in the quality of degree earned (as measured by average SAT score of matriculating students) that correspond exactly with the regional enrollment shifts observed in Table 5. Overall, students are 1.2 percentage points more likely to earn a degree from a Less Competitive institution, with the largest impacts in the Southwest region. In contrast, students in the West are 1.7 percentage points more likely to earn a degree from a Most Competitive institution, compared to a 1.1 point decline in the Southwest, although both results are statistically insignificant.

Finally, we examine the NHRP program for evidence of heterogeneous effects by student characteristics (Table 7). Each row is associated with a different subgroup and each column is associated with a different outcome, resulting in separate regressions for each cell. We first examine differences between students attending private versus public high schools, and find that our effects are driven entirely by public school students, where the base rates of the positive outcomes are much lower than in private schools. Although private school students are only a small portion of our overall sample, the results suggest this is not simply an issue of power, as almost all the coefficients for private high school students are small, at about 1 percentage point or smaller. As such, we focus only on public school students in the remaining rows in Table 7, noting that the inclusion of private school students would slightly diminish the magnitude of the results presented here.

| N | Four-year college | Recruiting institution | Out-of-state college | Barron's: Most Competitive | Bachelor's degree in four years | Bachelor's degree in six years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private high school | 5,655 | –0.007 | 0.038 | –0.012 | –0.012 | –0.009 | 0.004 |

| (0.017) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.027) | (0.028) | ||

| 88.8% | 37.8% | 38.3% | 26.8% | 49.5% | 68.7% | ||

| Public high School | 44,207 | 0.023** | 0.058** | 0.062** | 0.012 | 0.018+ | 0.013 |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.012) | ||

| 81.0% | 33.1% | 24.4% | 19.0% | 44.2% | 65.1% | ||

| Public high school: Location | |||||||

| City | 19,349 | 0.022+ | 0.060** | 0.047** | 0.017 | 0.005 | –0.005 |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.018) | ||

| 80.6% | 35.6% | 22.3% | 17.6% | 41.8% | 65.1% | ||

| Suburb | 16,890 | 0.031** | 0.053** | 0.061** | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.026 |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.018) | ||

| 80.5% | 28.9% | 26.9% | 22.9% | 47.0% | 65.0% | ||

| Town-Rural | 7,968 | 0.009 | 0.070** | 0.109** | 0.026 | 0.050* | 0.033 |

| (0.018) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.017) | (0.024) | (0.029) | ||

| 83.3% | 36.6% | 23.8% | 13.6% | 43.7% | 65.5% | ||

| Public high school: Hispanic concentration | |||||||

| Bottom 50th percentile | 18,285 | 0.010 | 0.060** | 0.064** | –0.007 | 0.008 | 0.021 |

| (0.011) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.018) | ||

| 82.2% | 34.5% | 28.7% | 16.0% | 45.7% | 65.9% | ||

| 50th to 75th percentile | 11,978 | 0.026+ | 0.073** | 0.061** | 0.007 | 0.007 | –0.007 |

| (0.015) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.019) | (0.022) | ||

| 77.8% | 31.9% | 21.1% | 19.7% | 45.2% | 67.9% | ||

| 75th to 100th percentile | 11,115 | 0.040** | 0.046** | 0.067** | 0.046** | 0.043* | 0.019 |

| (0.014) | (0.017) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.018) | (0.022) | ||

| 82.2% | 31.9% | 20.3% | 23.1% | 40.7% | 61.7% | ||

| Parental education | |||||||

| Bachelor or higher | 18,985 | 0.025** | 0.060** | 0.064** | –0.005 | –0.009 | –0.008 |

| (0.009) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.015) | (0.016) | ||

| 87.9% | 37.1% | 30.1% | 23.3% | 54.0% | 74.9% | ||

| High school graduate | 9,017 | 0.037* | 0.061** | 0.090** | 0.020 | 0.039+ | 0.038 |

| (0.017) | (0.021) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.022) | (0.027) | ||

| 80.5% | 33.1% | 19.1% | 15.9% | 38.4% | 60.7% | ||

| High school dropout | 7,595 | 0.022 | 0.049* | 0.036+ | 0.057** | 0.081** | 0.058+ |

| (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.025) | (0.031) | ||

| 78.0% | 30.8% | 19.0% | 21.3% | 38.4% | 60.4% | ||

| SAT tercile | |||||||

| Highest tercile | 9,996 | –0.006 | 0.022 | 0.032+ | –0.007 | –0.001 | –0.006 |

| (0.012) | (0.018) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.019) | (0.022) | ||

| 88.5% | 35.0% | 33.0% | 31.2% | 53.2% | 73.4% | ||

| Middle tercile | 10,519 | 0.049** | 0.047** | 0.075** | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.019 |

| (0.013) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.019) | (0.022) | ||

| 84.1% | 33.8% | 24.7% | 20.8% | 47.1% | 68.6% | ||

| Lowest tercile | 17,532 | 0.041** | 0.098** | 0.089** | 0.036** | 0.041* | 0.018 |

| (0.015) | (0.018) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.019) | (0.022) | ||

| 80.5% | 34.1% | 19.4% | 11.5% | 41.3% | 64.7% | ||

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. All regressions below the second row utilize only public school students. Results for earning a bachelor degree in six years utilize only five of the seven cohorts and sample sizes are correspondingly smaller. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

Overall, Table 7 shows significant impacts on sector of college attendance across all categories, but the strongest effects are found among students who attend high schools that have the highest concentrations of Hispanic students and are located in more rural environments. These students tend to experience the largest increases in four-year college enrollment and out-of-state college enrollment, as well as experiencing a 2 to 6 percentage point increase in the probability of attending a postsecondary institution in the Most Competitive category. We also find sizeable increases in four-year bachelor's completion that range from 4 to 8 percentage points among these disadvantaged students, who typically face the lowest completion rates. Six-year completion rates are generally smaller than the four-year results, though these results are still meaningfully large, but less imprecise as we lose the most recent two cohorts that do not have six-year outcomes.

We also attempt to examine differences in program impacts based on student academic performance. We utilize the fact that NHRP recognition does not impact any SAT measures in our previous analysis (see Table 4), and treat SAT score as exogenous. We use the sum of the Critical Reading and Mathematics subtests on students’ first SAT attempt, as this is both consistent across years and least subject to manipulation from subsequent re-taking. Although the PSAT and initial SAT are highly correlated, there are still substantial differences. The median initial composite (math + critical reading) SAT score on the 400 to 1600 scale for students within five points of the cutoff is 1230, and dividing the sample into equally sized terciles in this region indicates that the 33rd and 67th percentiles are 1190 and 1260, respectively. The bottom three rows of Table 7 show results by SAT tercile, and suggest that lower-scoring students exhibit the largest responses to NHRP. For example, shifts toward four-year, recruiting, and Most Competitive colleges increased by 4, 10, and 4 percentage points, respectively, for students in the bottom tercile. By contrast, the impacts for students in the highest tercile were either considerably smaller in magnitude or indistinguishable from zero. We also find that four-year bachelor degree completion rates for this lowest tercile group increased by almost 4 percentage points (10 percent). This finding is particularly noteworthy because these students have traditionally been most at risk for not completing.

DISCUSSION

The NHRP is an intervention that provides high-achieving Hispanic students positive information about their academic preparation for college, and provides colleges with an efficient method for identifying and recruiting a national sample of high-skilled minority students. The award seems to primarily serve as a tool for targeted outreach from colleges that these students otherwise would not have considered, namely, four-year institutions both out-of-state and at state flagships, though the award induces some students in particular areas to target and attend more selective, private institutions. Shifts in college choice appear to be strongest among students from predominantly Hispanic high schools, in rural areas, and among students with lower SAT scores. These results show that some colleges actively seek and are successful in enticing high-performing Hispanic students, which is consistent with a mission of creating a diverse and academically strong student body.

Even though there is relatively little effort in calculating NHRP eligibility and imparting this information to students and colleges, we do not think of this intervention as low-cost. Simply offering a student recognition for her academic performance is insufficient to achieve the college enrollment and completion effects documented in this study. In fact, providing a signal of relative within-ethnicity ability produces no measurable change in short-term academic performance, the most proximate area where we would expect to see changes in student behavior. Rather, our results suggest that college enrollment and completion effects are primarily driven by the higher-touch efforts on the part of colleges, such as increased interaction and generous financial aid, both of which follow NHRP recognition. Consistent with other research (e.g., Papay et al., 2015), these forms of support are shown to be particularly important for students and high schools with traditionally fewer resources, and that more effort to contact and communicate these opportunities toward recognized students may be fruitful in increasing postsecondary success.

Although increases in bachelor's completion do not always rise to the traditional levels of statistical significance, the coefficients suggest that, at the very least, the NHRP has no adverse impact on ultimate bachelor's completion. Based on the prevailing narrative on acclimation to college climate, students from predominately Hispanic high schools might be expected to suffer the largest culture shocks from attending colleges with comparatively small shares of Hispanic students. We find the opposite, as students from predominately Hispanic high schools actually experience large increases in four-year bachelor's completion of four percentage points. These findings challenge the narrative that unique cultural circumstances and intense family and community ties shared by Hispanic students might impede success at colleges far from home. Of course, family and community ties may still exert an influence on degree completion for Hispanic (or other) students and our completion results may be muted if altering college attendance patterns has a disruptive effect without appropriate supports in place.

There are a number of straightforward lessons to be taken from the NHRP program. First, inducing students to attend out-of-state colleges likely requires large financial incentives, given that all of the observed out-of-state shifting in this study is driven by colleges known to provide large grant aid packages. Second, this program allows colleges to effectively recruit Hispanic students attending a wide variety of high schools. The consistency of effects suggests that this program may serve as an alternative to traditional college outreach efforts, like deploying college admissions counselors to high schools and college fairs, and that direct outreach by colleges may be a more effective tool than policies that rely on individuals to proactively adopt a new set of behaviors. Our findings are consistent with those of other authors, such as Hoxby and Turner (2013), who find that direct outreach can be an efficacious way to impact student decisionmaking. In this case, we cannot be certain whether students exploit the information directly or indirectly through parents or counselors, who in turn advise students. Third, student responses are regionally specific, emphasizing the role of the higher education marketplace and local options in selecting which colleges to attend. Unfortunately, there is no convincing method by which we can identify what mechanisms lead to these regional differences. For example, impacts may be moderated by the relative distance of recruiting colleges; the availability of suitable in-state substitutes; or other state-based postsecondary policies such as merit aid, affirmative action, or guaranteed admission policies. Although we cannot causally explain the different choices across geographies, exploring differences in postsecondary decisionmaking across regions is worthy of future research and may shed light on some of these mechanisms.

The results in this study highlight that research needs to focus not just on completion impacts, but how interventions affect degree experience and quality. NHRP shifts the geographic distribution of degree completion, increasing the likelihood that West and Southwest students earn their bachelor degree out-of-state by approximately 25 percent. We cannot estimate whether this alters long-term residential mobility, and available evidence suggests effects might be small (Fitzpatrick & Jones, 2012; Groen, 2004). Nonetheless, these results could be meaningful for states looking to increase their stock of college-educated workers (Groen & White, 2004), particularly college-educated ethnic minorities. As most attendance is shifted toward public universities with generous financial aid, the states subsidizing these efforts might view these results as initial evidence of the strategy's efficacy. Shifting the type of institution where students earn their degrees could have further educational or labor force implications, if graduate schools or employers treat students differently based on the quality of the institution attended. Combined with the large financial aid packages offered by some colleges, students may also be completing with lower debt levels, which could have longer-term impacts on degree attainment or employment decisions (Field, 2009; Rothstein & Rouse, 2011). Finally, NHRP scholars may have a substantially different college experience and worldview as a result of their college choice, based on the fit between student and institution that may have been altered as a result of this program. Unobserved benefits to students, as well as to states that might retain these high-performing high school graduates, may be the biggest impact of all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper reflects the views of the authors and not that of their respective institutions. Oded Gurantz acknowledges support from grant R305B090016 from the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences.

APPENDIX

| Region | States | National PSAT takers | Hispanic PSAT takers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western | AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY | 848,655 (18.9%) | 180,628 (31.3%) |

| Southwestern | AR, NM, OK, TX | 532,680 (11.9%) | 165,330 (28.6%) |

| Southern | AL, FL, GA, KY, LA, NC, SC, TN, VA, MS | 830,585 (18.5%) | 65,844 (11.4%) |

| New England | CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT | 359,879 (8.0%) | 25,150 (4.4%) |

| Middle States | DC, DE, MD, NJ, NY, PA | 1,062,447 (23.6%) | 107,016 (18.5%) |

| Midwestern | IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI, WV | 861,353 (19.2%) | 33,428 (5.8%) |

| Total | N = 4,495,599 | N = 577,396 |

| Non-recruiting institutions | Recruiting institutions | Core recruiting institutions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Flagship | 2.4% | 15.3% | 6.5% | 24.7% | 57.1% | 53.5% |

| Private | 64.8% | 47.8% | 61.9% | 48.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 3.1% | 17.4% | 8.7% | 28.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | 4.0% | 19.7% | 15.5% | 36.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 15.7% | 36.4% | 26.6% | 44.3% | 42.9% | 53.5% |

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 77.1% | 42.0% | 49.2% | 50.1% | 57.1% | 53.5% |

| Total enrollment | 4,580 | 5,740 | 7,380 | 8,443 | 24,016 | 8,604 |

| Mean SAT of college | 1046 | 124 | 1120 | 138 | 1113 | 35 |

| Graduation rate in 150% time | 50.8% | 18.1% | 60.8% | 17.6% | 57.9% | 7.1% |

| Expenditures per FTE | $16,961 | $15,673 | $20,332 | $13,775 | $14,273 | $3,075 |

| Tuition | $15,543 | $9,304 | $18,518 | $11,227 | $5,404 | $570 |

| Percentage Hispanic | 7.1% | 13.6% | 7.5% | 10.2% | 10.5% | 12.1% |

| Number of institutions | 1,215 | 323 | 7 | |||

- Notes: Data include only four-year institutions. All variables derive from IPEDS data except for flagship status and Barron's rankings.

| Bandwidth | 20 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15, PSAT<200 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel | Tri | Tri | Tri | Tri | Rect | Rect | Rect | Rect | Rect | Rect | Rect | Rect |

| Functional form | Linear | Linear | Linear | Linear | Linear | Linear | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad | Linear | Linear |

| Covar | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Standard errors | Robust | Robust | Robust | Clustered | Robust | Robust | Clustered | Robust | Robust | Robust | Robust | Robust |

| Fixed effect (by year) | State | State | State | State | State | State | State | State | State | State | School | State |

| Recruiting institution | 0.052** | 0.054** | 0.049** | 0.054** | 0.052** | 0.055** | 0.053** | 0.056** | 0.053** | 0.056** | 0.050** | 0.050** |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Two-year college | –0.012* | –0.011+ | –0.011 | –0.011* | –0.010* | –0.014* | –0.010+ | –0.012 | –0.010+ | –0.011 | –0.012* | –0.012* |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.005) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Four-year college | 0.016** | 0.017* | 0.016+ | 0.017* | 0.013* | 0.021** | 0.015* | 0.020* | 0.015* | 0.019* | 0.015* | 0.015* |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Out-of-state college | 0.049** | 0.044** | 0.036** | 0.044** | 0.055** | 0.048** | 0.047** | 0.041** | 0.047** | 0.041** | 0.050** | 0.051** |

| (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Flagship | 0.027** | 0.032** | 0.035** | 0.032** | 0.023** | 0.033** | 0.029** | 0.038** | 0.029** | 0.037** | 0.030** | 0.029** |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Private | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.004 | –0.002 | 0.007 | –0.002 | 0.007 | –0.005 | –0.004 |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.011) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.008) | (0.009) | |

| Barron's: Most | 0.005 | 0.001 | –0.004 | 0.001 | 0.010 | –0.003 | 0.005 | –0.004 | 0.004 | –0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| Competitive | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.007) |

| Barron's: Less | 0.017* | 0.017* | 0.019+ | 0.017* | 0.014* | 0.019* | 0.016* | 0.017 | 0.016* | 0.017 | 0.017* | 0.018* |

| Competitive | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.008) |

- Notes: Results based on regressions that include state-by-year fixed effects. School or state fixed effects are interacted with each cohort year. Covariates included a dummy for being female and various parental education and income levels; previous PSAT score for those who took the exam in 10th grade; dummies for various Hispanic ethnicities; and dummies to control for high school status (public or private), type (city, suburban, town/rural), size, and Hispanic concentration. The final column removes all students scoring 200 or more on the PSAT, to eliminate any potential effects from National Merit Commended status.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

| All regions | West region | Southwest region | All other regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Control | Control | Control | |||||

| Effect | mean | Effect | mean | Effect | mean | Effect | mean | |

| Score sends | ||||||||

| Total | 0.252** | 7.0 | 0.263 | 7.4 | 0.195 | 6.0 | 0.285+ | 7.2 |

| (0.095) | (0.175) | (0.157) | (0.156) | |||||

| College SAT: Minimum | –6.215* | 1103 | –3.806 | 1084 | –9.771+ | 1077 | –5.706 | 1132 |

| (2.762) | (4.653) | (5.192) | (4.538) | |||||

| College SAT: Maximum | 0.327 | 1376 | 2.510 | 1373 | –11.339+ | 1345 | 6.924+ | 1397 |

| (2.912) | (5.360) | (6.088) | (4.044) | |||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | 0.041 | 2.6 | 0.004 | 2.9 | –0.093 | 1.7 | 0.160 | 3.0 |

| (0.069) | (0.124) | (0.103) | (0.121) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | 0.027 | 1.5 | 0.085 | 1.2 | –0.038 | 1.6 | 0.029 | 1.6 |

| (0.034) | (0.056) | (0.058) | (0.060) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 0.046 | 1.2 | 0.088 | 1.7 | 0.110* | 1.0 | –0.026 | 1.1 |

| (0.032) | (0.064) | (0.056) | (0.045) | |||||

| Barron's: Less Competitive | 0.152** | 0.9 | 0.153* | 1.0 | 0.280** | 1.2 | 0.061 | 0.8 |

| (0.032) | (0.061) | (0.063) | (0.045) | |||||

| College sector | ||||||||

| Two-year college | –0.009 | 8.9% | –0.011 | 13.7% | –0.008 | 10.0% | –0.009 | 4.7% |

| (0.006) | (0.014) | (0.012) | (0.007) | |||||

| Four-year college | 0.014+ | 84.3% | 0.013 | 80.5% | 0.018 | 84.3% | 0.013 | 87.1% |

| (0.008) | (0.016) | (0.015) | (0.011) | |||||

| Recruiting institution | 0.048** | 29.0% | 0.068** | 16.8% | 0.071** | 43.8% | 0.017 | 28.7% |

| (0.010) | (0.016) | (0.021) | (0.016) | |||||

| Core seven recruiting institution | 0.051** | 3.4% | 0.055** | 6.1% | 0.084** | 5.3% | 0.024** | 0.2% |

| (0.005) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.005) | |||||

| Other non-core recruiting institution | –0.034** | 55.3% | –0.055** | 63.7% | –0.053** | 40.6% | –0.003 | 58.4% |

| (0.011) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.017) | |||||

| Out-of-state college | 0.047** | 33.0% | 0.080** | 28.4% | 0.067** | 22.1% | 0.008 | 43.1% |

| (0.010) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.017) | |||||

| Flagship | 0.023** | 16.1% | 0.030* | 11.9% | 0.013 | 18.1% | 0.024+ | 18.0% |

| (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.014) | |||||

| Private | –0.001 | 38.9% | 0.029 | 32.0% | –0.050** | 30.6% | 0.012 | 49.1% |

| (0.011) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.017) | |||||

| Barron's: Most Competitive | –0.001 | 26.9% | 0.019 | 25.0% | –0.009 | 11.4% | –0.012 | 38.0% |

| (0.009) | (0.018) | (0.013) | (0.017) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive Plus | –0.005 | 19.8% | –0.005 | 12.2% | –0.019 | 26.7% | 0.005 | 21.1% |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.019) | (0.015) | |||||

| Barron's: Highly Competitive | 0.005 | 18.0% | –0.008 | 25.0% | 0.011 | 13.2% | 0.012 | 16.0% |

| (0.009) | (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.013) | |||||

| All other four-year institutions | 0.016+ | 19.5% | 0.007 | 18.3% | 0.036+ | 33.1% | 0.008 | 12.0% |

| (0.009) | (0.017) | (0.020) | (0.012) | |||||

| College characteristics (IPEDS) | ||||||||

| Mean SAT of college | –1.959 | 1219 | 2.576 | 1211 | –5.942 | 1155 | –2.287 | 1262 |

| (3.298) | (6.276) | (6.250) | (4.921) | |||||

| Graduation rate in 150% time | –0.625 | 72.5 | –0.421 | 74.5 | –0.667 | 62.1 | –0.712 | 77.3 |

| (0.421) | (0.720) | (0.928) | (0.592) | |||||

| Expenditures per FTE | –631.487 | $28,298 | 569.510 | $25,880 | –3,187.384** | $27,782 | 90.125 | $30,411 |

| (578.482) | (856.401) | (1,149.605) | (988.301) | |||||

| Tuition | –236.277 | $18,140 | 934.104 | $15,612 | –1,678.245** | $14,746 | –192.834 | $22,003 |

| (325.503) | (605.105) | (556.891) | (521.801) | |||||

| Percentage Hispanic | –0.007* | 15.4% | –0.006 | 15.3% | –0.010 | 24.1% | –0.005 | 9.9% |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.004) | |||||

| N | 33,277 | 10,349 | 9,732 | 13,196 | ||||

- Notes: Results based on linear regressions with rectangular kernels that include state by year fixed effects. Robust standard errors are in parentheses.

- +p ≤ 0.10; *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01.

| All regions | West region | Southwest region | All other regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Control | Control | Control | |||||

| Effect | mean | Effect | mean | Effect | mean | Effect | mean | |

| All students | 0.012 | 65.9% | 0.017 | 65.7% | –0.009 | 63.6% | 0.038+ | 69.6% |

| (0.010) | (0.016) | (0.017) | (0.020) | |||||

| Recruiting institution | 0.037** | 26.2% | 0.046** | 18.9% | 0.040* | 38.0% | 0.015 | 21.1% |

| (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.017) | (0.019) | |||||

| Core seven recruiting institution | 0.040** | 2.9% | 0.033** | 4.3% | 0.065** | 3.4% | 0.011* | 0.0% |

| (0.004) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.005) | |||||

| Other non-core recruiting institution | –0.025** | 39.7% | –0.029+ | 46.9% | –0.048** | 25.6% | 0.023 | 48.5% |

| (0.010) | (0.016) | (0.014) | (0.022) | |||||