Strengthening state capacity in Africa: Lessons from the Washington versus Beijing Consensus

Abstract

Africa is currently the only continent that is yet to experience sustained industrial growth and structural transformation. The continent's position as the last frontier for industrial growth became clear following the spectacular transformations of the Chinese economy since the late 1970s. While it is often emphasized that Africa must improve its industrial capacities and diversify its economies in order to achieve real growth and development, there is little clarity on the most effective model and strategies for the continent's industrialization. This article conceptually examines the Washington Consensus versus the Beijing development models, and empirically presents their evolution in Africa. Drawing on a modified Fukuyama's state theory which differentiates between the strength of state institutions and the scope of state activities, this article argues that strengthening African states is a prerequisite for the success of any development model. The article provides strategies for strengthening state capacity in African countries from weak to moderately strong states.

1 INTRODUCTION

By volume of industrial production and export, Africa ranks last among other continents (World Bank, 2016). Weak industrial capacity has meant weak economies and poor social outcomes, resulting in a devastating social hierarchy with Africa having the largest number of poor people in the world (World Bank, 2018a). Given Africa's grim economic and social indicators, the continent's foreign development partners, especially from the West, have been persistent in calling on African countries to embrace economic and political reforms that would open up the countries' respective markets, reduce government interventions in the economy, and unleash the ingenuity and efficiency of the private sector (Falola & Kalu, 2018; Padayachee & Fine, 2019). Since the 1980s, African countries have experimented with policy prescriptions, driven especially by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These policies, which collectively encompass the Washington Consensus, were earlier packaged as the structural adjustment program (SAP) (Helleiner, 2003; Mkandawire & Soludo, 1999; Stiglitz, 2003), and have since evolved into different policy support instruments often directed by the World Bank, the IMF and other multilateral donors.

The Washington Consensus model recommended privatization of public enterprises, focus on price stability, liberalization of interest rates and financial markets, deregulation of foreign direct investment and removal of government controls over the economy, among others (Williamson, 1994). The Washington Consensus model argues that markets will eliminate inefficiencies, remove the opportunities for rent-seeking by public officials and produce greater benefits to the society (Babb, 2013; Santiso, 2004a). These neoliberal beliefs anchored on the self-regulating power of markets were assumed to work in any society irrespective of the initial conditions in such society and irrespective of the institutional environment. The assumption was that competition will drive inefficient agents to either increase productivity or to give way to more efficient competitors (Williamson, 2004, 2009). However, as the world would eventually learn from the disasters that followed episodes of economic liberalization, especially in parts of Africa, markets do not necessarily have the power of self-regulation. In an assessment of the performance of SAP across Africa, Adedeji (1999, p. 522) concludes “that even for the narrow economistic objective of growth in real per capita GDP, the record of SAP over the two decades has been quite disappointing”, with many countries reporting negative growth in real per capita GDP following the adoption of SAP. In addition, Stein et al. (2002), and Mkandawire and Soludo (1999) show that Nigeria, Ghana and many other African countries experienced bank failures and systemic financial crisis because extant institutions could not effectively regulate the financial system following liberalization. Adedeji (1999) observes that SAP was based on incorrect understanding of the problems of underdevelopment in general, as well as the political economy of most African states, in particular. Given the unintended consequences of liberalization, economists and development practitioners are coming to terms with the principal role of institutions in regulating markets, influencing the behavior of agents and shaping economic growth and development (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2013; North, 1990).

As an alternative to the Washington Consensus, China has followed an economic model that puts the state on the driver's seat. Standing in opposition to the assumption of universality ascribed to neoliberal orthodoxy, the Beijing model involves carefully orchestrated state industrial policies, and state-managed process of gradual liberalization. Described by some scholars as the Beijing Consensus, China's economic model is anchored on the principle of self-determination, to the effect that countries should be free to fit into the global political economy according to their own peculiarities (Ramo, 2004; World Bank, 1993). The Beijing model is also viewed as a developmental state approach for its focus on citizens' well-being as a measure of development, rather than focusing exclusively on GDP numbers. The Beijing Consensus is mostly validated by China's phenomenal economic growth during the past three decades when it has maintained state intervention as a distinctly anti-Washington Consensus feature in the economy (Ferchen, 2013). However, while some African countries have started looking up to the China in search of their own developmental path, evidence has been rare that African governments have necessarily implemented policies that are far removed from those prescribed by the original Washington consensus (Babb, 2013). An example is the foreign direct investment (FDI) regime, for which the Beijing model would famously put conditions such as technology transfer and local supplier participation (Mortimore & Stanley, 2010). Even when an African country actively engages China, it tends not to pay attention to the aforementioned condition of technology transfer, but somehow continues to embrace the neoliberal laissez-faire policies in handling FDI from China (Kragelund, 2009).

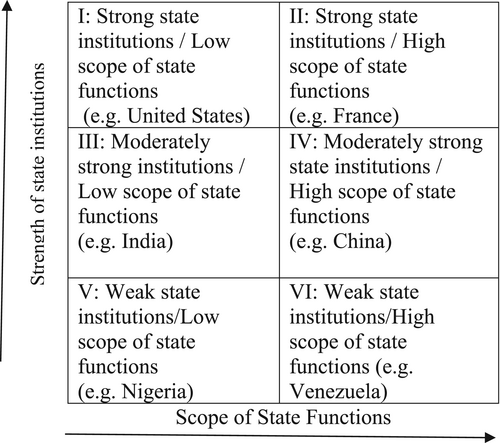

The article departs from previous studies as it seeks to answer the following pertinent questions: How have the Washington Consensus and the Beijing development models evolved in African countries? Is any of the models more suitable for economic advancement and transformation of African countries? What should African countries do to strengthen state capacity? The article adopts the following approaches in order to answer these questions: First, it examines the Washington Consensus and the Beijing development models, and uses archival data from the World Bank and the IMF to assess their evolution in Africa. Second, it constructs a modified Fukuyama's state theory which differentiates between the strength of state institutions and the scope of state activities (Fukuyuma, 2004). Third, this study argues that the critical developmental challenge for African countries hinges on strengthening public institutions and state capacities, and not a policy choice between the Washington and Beijing Consensus. Last, the article proposes and discusses how state capacities in Africa can be strengthened using a multiplicity of reform efforts that focus on critical institutions, accountability, civil society groups, attitudes and values, engagement of diaspora and public-private partnerships.

2 THE EVOLUTION OF WASHINGTON CONSENSUS

The Washington Consensus was initially designed for structural reforms in Latin American countries (Santiso, 2004a; Williamson, 1993, 2000, 2009). At a conference convened by the Institute for International Economics in 1989, John Williamson presented a list of 10 neo-liberal reforms accepted within OECD countries to guide the Latin American economic reforms, which he termed the “Washington Consensus”. Richard Feinberg immediately challenged the term as inappropriate, arguing that it was not generally endorsed by Washington (Williamson, 1993, 2004). Although, episodes of intense ideological controversy ensued, the Washington Consensus became entrenched as a viable economic and political reform prescription for Latin America and other developing countries. It gained enthusiastic support of powerful political leaders including the Conservative British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, to the effect that she claimed “there is no alternative to the Washington Consensus” (Beeson & Islam, 2005; Helleiner, 2003). The Washington Consensus comprises of 10 broad policies: 1) adopting fiscal discipline that reduces deficit and inflation, 2) prioritizing public expenditures on basic infrastructures, education and health to promote growth and focus on the poor, 3) reforming the tax system to broaden the tax base and adopt moderate marginal tax rates, 4) liberalizing interest rates, 5) maintaining competitive exchange rates, 6) liberalizing trade, 7) liberalizing inward foreign direct investment, 8) privatizing state enterprises, 9) deregulating the economy to lower barriers to entry and exit, and 10) granting property rights to the informal sector (Williamson, 2009). In summary, privatization, financial reforms, and economic and political liberalization were promoted under the Washington Consensus (Huang, 2010).

The Washington Consensus has been widely studied, albeit highly contentious. It has been described as a “summary of the lowest common denominator of policy advice” (Williamson, 2000, p. 251), and an ‘exclusively instrumentalist’ model (Babaci-Wilhite et al., 2013). Many studies suggest that developing countries relying on free trade experience higher economic growth than countries engaging in protectionism (e.g., Bauer, 1984; Edwards, 1992; Grossman & Helpman, 1993; Harrison, 1996). Similarly, the benefits of trade liberalization could come from various channels including improved resource allocation, exposure to better technology, economies of scale, transfer of know-how, and favorable growth opportunities (Dornbusch, 1992).

The Washington Consensus garnered supports from powerful political actors in Washington who challenged the notion that states must intervene in economic activities to protect public interest. As Ban and Blyth (2013) suggest, the politics of spreading the Washington Consensus around the world is closely linked to the domestic American politics. The Consensus inspired a surge of reforms that altered policy landscape in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and even in socialist countries after the fall of the Berlin wall (Rodrick, 2006). However, this neo-liberal model and policies failed to produce the desired results, leading to disenchantment with the reform agenda. For example, Latin America which pursued macroeconomic policies and reforms prescribed by the Washington Consensus for approximately two decades (Morrison, 2011) still experienced a series of economic shocks and crises such as the 1994–1995 tequila crisis in Mexico, the 1998–1999 samba crisis in Brazil, and the 1999–2002 economic crisis in Argentina (Santiso, 2004a).

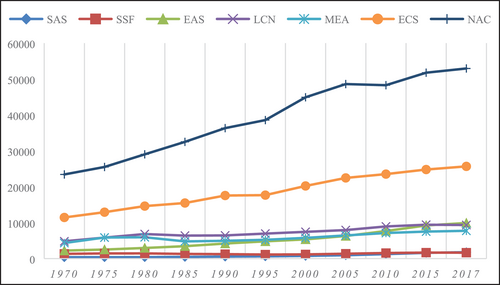

Similarly, there were substantial reforms driven by the Washington Consensus in Africa in the 1980s and 1990s, that led to market-based outcomes such as considerable increase in privatization, trade liberalization, and dissolution of state marketing boards (Ancharaz, 2003; Rodrick, 2006), but these neo-liberal reforms also fell short of expectations, as the reforms proved grossly inadequate in tackling the complex development challenges plaguing the continent (Helleiner, 2003; Mkandawire & Soludo, 1999). The Bretton Wood institutions, which were significantly influenced by the Washington Consensus reform policies, imposed conditions for providing financial assistance aimed at encouraging reforms (a performance-based aid), and their agenda could include attempts to alter the political framework of the recipient country (McKinnon, 2010; Van Waeyenberge, 2009). The structural adjustment programs inevitably failed, as their designs were inappropriate for the institutions implementing them in developing countries, and the conditions imposed proved ineffective in advancing reforms (Santiso, 2004b; Stiglitz, 2003). Babb (2013) adds that it was this practice of insisting that certain conditions be met before grant of financial assistance that ultimately weakened the Washington Consensus as a development model in developing countries. As depicted in Figure 1 below, the Washington Consensus model failed to improve the GDP per Capita in Sub-Saharan African countries relative to other regions.

In summary, the experiences of Africa and elsewhere suggest that, as a policy paradigm (Babb, 2013; Reyes, 2017), the Washington Consensus became a damaged brand name too narrow to claim universal applicability, and it failed to deliver on promises of trickle-down effects and a way to wrestle power from oligarchs (Florio, 2002; Plehwe, 2007; Williamson, 2003). In the next section, we discuss China's development model as an alternative model.

3 THE BEIJING CONSENSUS AS AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL

The term Beijing Consensus (BC) which was originally coined by Ramo (2004) and subsequently revised by Li et al. (2010) consists of 10 economic principles which have formed the foundations of China's development model. The principles are: localization of borrowed best practices, combination of free market capitalism and planned communism, flexible means to a common goal, freedom to choose strategy and policy for building one's economy, stable political environment, self-reliance, constantly upgrading industry, indigenous innovation, prudent financial liberalization and economic growth for social harmony. A number of scholars identify the period, 1978–1979 as the beginning of China's economic reform that has produced rapid economic growth and structural transformation, leading to the emergence of what is now widely described as the Beijing model (Guan, 2017; Tantri, 2013; Wu, 2005). Led by Deng Xiaoping, the early stages of China's economic reforms included the establishment of the first four special economic zones (SEZs) that led to spectacular growth in industrial production, and that paved the way for China's emergence as a global manufacturing hub (Halper, 2010; Naughton, 2007).

While China has achieved rapid industrialization during the past four decades, a number of studies argue that China's state-led industrialization has been used previously by Japan and other East Asian economies, albeit with modifications (Bird et al., 2012; Givens, 2011). In addition, Kennedy (2010, p. 461) argues that the Beijing Consensus “is a misguided and inaccurate summary of China's actual reform experience”. Along the same line, Williamson (2010) notes that the so-called Beijing Consensus only represents outsiders' perceptions of what China does. These studies question the uniqueness of China's economic model, and contend that there is in fact no “consensus” around Beijing's macroeconomic management or industrial policy. China's economic model shares similarities and differences with those of many countries, including both capitalist regimes and those of developmental states. Rodrick (2006) documents that China increased its reliance on market forces, but with policies that were largely unconventional. Relatedly, Lin (2015, p. 98) notes that China transitioned from a “planned economy to a market economy”, and between 1978 and 1990, the transition led to remarkable economic development. According to Kennedy (2010), the Beijing Consensus (BC) is more appropriately regarded as a concept designed to promote China's economic successes and to challenge the universality of the Washington Consensus model. Continuing, Kennedy argues that “as a piece of analysis, the BC (Beijing Consensus) is relatively incoherent and largely inaccurate” (p. 467). Although these studies question the existence of a coherent economic management model that could be described as the Beijing Consensus, there appear to be a common understanding that China has not followed neoliberal economic model that defines the Washington Consensus.

Prior studies suggest that the West has had a free reign without a serious rival in Africa until China emerged with a strong desire for business, financial means to assist in development, subtle strategy to adapt and prosper, and fervent political will (Alden et al., 2008; Mekonnen & Eshete, 2015). In effect, economic, political and social developments took new dimensions across Africa, following China's economic surge and political influence (Prah & Gumede, 2018; Zondi, 2018). Through rising trades, aid flows, state sponsored initiatives, and various activities of independent Chinese migrants, China has become a key player in the development of Africa (Amanor & Chichava, 2016; Cook et al., 2016; French, 2014; Gu et al., 2016; Wang & Bio-Tchané, 2008).

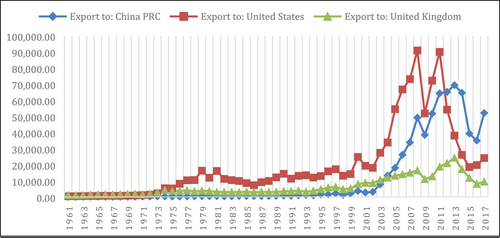

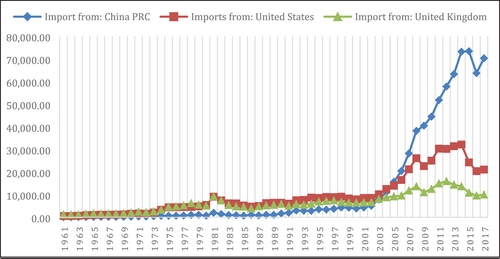

This study finds that from 2000 to 2017, the total export and import of merchandize goods, based on IMF trade data, between China and North African countries including Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, Sudan and Tunisia, increased from US$2888.53 billion to US$30,407.45 billion, an increase of roughly 953%. Similarly, China's trade in merchandize goods with Sub-Saharan Africa rose from US$10,035.06 billion in 2000 to US$143,751.22 billion in 2017, an increase of 1322% in less than two decades. As shown in Figures 2 and 3 below, China has surpassed the US and the UK as Africa's major trading partner. Statistics from Chinese Customs further shows that the growth of trade between China and Africa was only lower than the growth of China's trade with Oceania and Latin America, and the value for the China–Africa import and export of both merchandize goods and services for 2017 amounted to US$170 billion, up 14.1% year on year (Ministry of Commerce People's Republic of China, 2018).

Coincidentally, the emergence of China as a major development partner in Africa occurred at a time when the continent was engulfed in soul-searching to uncover what went wrong in their development efforts since gaining independence from Europe and in exploring alternative feasible development frameworks (Cheru & Obi, 2010; Prah & Gumede, 2018). China also emerged when foreign direct investments to Africa were progressively declining (Kachiga, 2013). Although, China did not suddenly appear in Africa as the two have been in contact for many centuries that date back to the precolonial era between 700 CE and 1800 (Mazimhaka, 2013), the partnership took new dimensions in the postcolonial era (Gu et al., 2016; Prah & Gumede, 2018; Taylor, 2011). Taylor (2011) provides a historical account of China's relationships with Africa, and notes that between 1955 and the mid-1970s, China greatly expanded relations with African countries as these African countries gained independence; and African states, in turn, helped China to gain admission to the United Nations. However, China's investment interest in Africa waned between the mid-1970s and 1989 in preference to relationships with the West, but China revised its foreign policies toward developing countries between 1989 and 2000 and returned to Africa. In 2000, China's economic interest in Africa heightened and culminated in the formation of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Since the formation of FOCAC, trade and investments flow between China and Africa have increased at unprecedented rates (Bräutigam, 2009; Taylor, 2011; Wang & Bio-Tchané, 2008).

4 BUILDING STATE CAPACITY

Against the neoliberal belief that the state is a problem, and markets the solution, Fukuyama (2017) argues that a capable state is a precondition for economic advancement, while weak and failed states have always been a source of severe difficulties, particularly in the developing world. There have been debates over the proper scope of state functions, but there has been much less attention to the strength of the state, that is, the government's ability to maintain law and order, protect property rights, and effectively implement its own policies and programs. In Fukuyama's thesis on state-building, scope refers to the different functions and goals taken on by the state, whereas strength equals the state's ability to plan and execute policies, and enforce laws. Theoretically, a major difference between the Washington Consensus model, which advocates for free markets and limited state intervention, and the Beijing model which pushes for state's active involvement in shaping the economy, is the scope of state involvement in economic activities and development planning. Each of the models assumes that state has the capacity to effectively deliver on whatever it chooses to focus on. Under the neoliberal economic model, the state must have the capacity to provide the right institutions such as effective property rights, efficient judiciary, sound macroeconomic management and a general atmosphere of peace and order that would enable private businesses to thrive.

According to Fukuyuma (2004, p. 28), “while privatization involves a reduction in the scope of state functions, it requires a high degree of state capacity to implement.” Most of the challenges with market reforms in African states stem from lack of efficient institutions to support market forces. Along this line, Stein et al. (2002) use a case study of banking sector liberalization in Nigeria to show how state capacity is important in shaping the results of market-based policies. The authors show that instead of enhancing financial depth and promoting efficiency in the Nigerian banking sector, banking liberalization “liberalized” corruption and brought about systemic distress in the sector, largely because state institutions did not have the capacity for effective supervision of the banks.

The Beijing model thrives on a combination of strength and scope—the state must have the capacity (strength) to execute its programs successfully, and also exercise authority and control over a wide range of economic activities. To be able to successfully formulate and implement industrial policies, the state must have sufficient strength to follow through with short, medium and long-term development goals. The developmental state is therefore one that not only displays strong state institutions, but also undertakes a large scope of activities in the economy. The appropriate question for African countries therefore is not necessarily which of the economic models to adopt, but more about the capacity of the state and its institutions to initiate, and effectively implement growth-oriented policies and programs. Fukuyuma (2004) suggests that the US has strong institutions and low scope of state functions; France has strong institutions and also high scope of state functions; Brazil and Turkey have high scope of state functions but weak institutions, and Sierra Leone has both weak institutions and low scope of state functions. This article modifies Fukuyama's state theory to include moderately strong state institutions such as China, consistent with our argument that the strength of state institutions has permitted China to successfully project a different kind of capitalism, which some scholars have called “state capitalism” (e.g., Gu et al., 2016). Figure 4 below presents our modified model.

Figure 4 shows six congruent rectangles. Strong states with efficient institutions, but little direct involvement in the economy would be in rectangle I. The United States with its functional government and strong institutions (but where the state focuses on providing enabling environment for the private sector) can be seen in rectangle I. On the other hand, France which has strong and effective institutions, and relatively active state involvements or history of intervention in the economy (Jabko & Massoc, 2012; Stothard, 2016), will be in rectangle II. Rectangle III countries combine moderately strong state capacities and low state involvement in the economy. A country like India has moderately strong institutions and relatively low scope of state functions. Countries with moderately strong state institutions and high scope of state functions are in rectangle IV. This is where China fits. Rectangles V and VI are for countries with weak institutions. While rectangle V countries have low scope of state functions, rectangle VI countries have high state involvement as in Venezuela. Nigeria is an example of a country with weak state institutions, and low scope of state functions fueled by structural adjustment programs. Virtually all African countries also have weak state institutions and low scope of state functions. We argue that for weak countries, it makes no difference whether the state chooses to play active roles in the economy or not. This is because lack of state capacity means the state is ineffective whether it chooses to play major roles in the economy or mainly provide the enabling environment for the private sector. The basic foundation of every development model is an enabling state supported by appropriate institutions. The strength of the state is represented by its ability to make and enforce laws, conduct government businesses with relative effectiveness, and formulate desired policies and execute such policies accordingly. It also includes the ability of the state to fight bribery and corruption, enthrone rule of law and create an environment that is conducive for private agents to pursue their lawful businesses without hindrance (North, 1990; Acemoglu and Johnson, 2005).

5 ASSESSING STATE CAPACITIES IN AFRICA

It is important to acknowledge that Africa is made up of several countries at different levels of economic and political development. However, one must note too that many African countries have similar institutional characteristics based largely on the continent's unique history and political evolution (Young, 2012). Governance institutions across most of Africa are decidedly weak, and the state in many cases are predatory, indicating that state's resources are often diverted to serve only a few elites (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2010; Mazrui & Wiafe-Amoako, 2016; Thomson, 2010). Predatory states create and sustain institutions that facilitate exploitation of the commonwealth in favor of political leaders and their cronies. Because they concentrate on satisfying the selfish desires of a few elites, predatory states are incapable of initiating, executing and sustaining programs that would enlarge society's welfare. The brand of political leadership and institutions prevalent in African states has necessitated such labels as neopatrimonial, patriarchal, prebendalist, authoritarian, and dictatorial—all pejorative attributes that indicate state's palpable failure to create the environment for sustainable development and citizens' welfare (Beekers & van Gool, 2012; Clapham, 1985; Joseph, 1987).

In Table 1 below, we report the 2017 Government Effectiveness Rank (GER) of selected countries at different levels of development. The GER is a subset of the World Bank's World Governance Indicators. It reflects the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence, as well as the quality of policy formulation and implementation in any country. The GER also indicates the credibility of a government's commitments to its own policies (World Bank, 2018b). Simply put, it measures the institutional quality of a country. The GER ranges from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest). As can be seen in the table below, the GER of the countries listed under Europe and North America are by far higher than those of African countries. Similarly, the GER of the four Asian countries listed are much higher than those of African countries. Of the 10 largest African economies listed on the table, only South Africa had a GER higher than 50. It is also instructive that South Africa has a political and institutional evolution that is distinct from those of the rest of Africa. For example, South Africa was a settler colony where European imperialists chose to settle, which also made it imperative for the colonizers to establish efficient and inclusive institutions in the section of the country where the colonizers settled (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2013). With very low levels of government effectiveness in the average African country, it is not clear how these countries can successfully implement either the market-based economic model or the Beijing model of state-managed economic system.

| S/no | Country | Government effectiveness rank (2017) |

|---|---|---|

| Europe and North America | ||

| 1 | Canada | 97.12 |

| 2 | France | 87.98 |

| 3 | Germany | 94.23 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 99.52 |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 90.87 |

| 6 | United States | 92.79 |

| Asia | ||

| 1 | China | 68.27 |

| 2 | Malaysia | 76.44 |

| 3 | Singapore | 100 |

| 4 | South Korea | 82.21 |

| Africa | ||

| 1 | Algeria | 30.29 |

| 2 | Angola | 14.90 |

| 3 | Egypt | 29.33 |

| 4 | Ethiopia | 23.56 |

| 5 | Kenya | 40.87 |

| 6 | Libya | 2.40 |

| 7 | Morocco | 47.60 |

| 8 | Nigeria | 16.35 |

| 9 | South Africa | 65.38 |

| 10 | Sudan | 7.21 |

- Source: World Bank's World Governance Indicators (2018a).

It is pertinent to acknowledge that Africa's political and economic systems and institutions are evolving. Some forms of democratic elections are taking place across the continent. However, even these elections are shaped by extant institutions (Przeworski, 2009), and this is why electoral fraud, and suppression of the true wishes of the electorates remain widespread across the continent. Mazrui and Wiafe-Amoako (2016, p. 4) observe that “democracy and its practice in Africa is viewed suspiciously, with leaders, at the least opportunity, trying to change the rules to cling to power for as long as possible.” Little wonder that measures of institutional quality in Africa have not seen significant enhancement over the past two decades despite the often-celebrated wave of democratization in the continent.

6 STRATEGIES TO STRENGTHEN STATE CAPACITIES IN AFRICA

There are certainly no universal recipes for strengthening the capacity of a state. Building a strong and capable state is a complex process, and especially difficult for developing countries formerly under colonial rule (Migdal, 1988). While “strong state” may be used in the context of state's ability to maintain social control, as in autocratic states, the emphasis in this article is more on efficient and capable states that are able to initiate and effectively implement developmental and welfare-enhancing policies. Formal and informal institutions, including norms, customs and other nonstate organs play important roles in the actions and choices of citizens and other agents, and equally play central roles in the ability of the state to effectively implement its policies (Hodgson, 2006; Kalu, 2017; Lund, 2006; North, 1990). Therefore, any program designed to strengthen state capacities must go beyond the usual cliché of public service reforms, or capacity building for bureaucrats and elected officials, but must incorporate series of reforms targeted at relevant nonstate institutions, including customs and belief systems (Levy, 2007). Consequently, the recommendations for strengthening the capacities of African countries are anchored on two important pillars. First, is an acknowledgement that African countries are at different levels of development and have different governance capacities, implying that what works in one country may need modifications in order to work in another. Second, the more complex and often nebulous informal norms and practices exert equally significant influence on the ability of the state to effectively carry out its lawful duties. Therefore, strengthening state capacity to execute its functions must include programs directed at altering agents' behavior and worldviews where necessary.

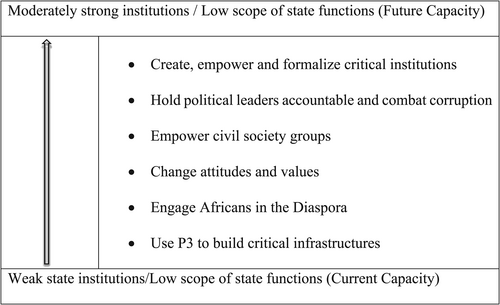

Nonetheless, since most African countries have weak state institutions and low scope of state functions similar to Nigeria in the modified state capacity model, we present specific recommendations for transitioning to moderately strong institutions and low scope of state functions. A model of our recommended strategies is provided below:

6.1 Formalization and institutional complementarity

Perhaps an important starting point to strengthening state capacity is for state actors to create, empower and formalize critical institutions such as a functional public service managed by professionals and driven by merit (Kisner & Vigoda-Gadot, 2017), a judicial system that is efficient in interpreting the laws of the land, and an effective mechanism for law enforcement, among others. These formal institutions should not depend on the whims of the political leaders, but must be independent, formalized and follow predictable processes (Moore, 1978). It is the institutional characteristic of predictability that helps to reduce transaction costs as agents are confident of state's ability to enforce its laws (North, 1990).

In addition to setting up requisite formal institutions to carry out the functions of the state, there must be some form of congruence and complementarity across the different institutions. Institutional complementarity is important in the political economy (Hall & Gingerich, 2009; Hall & Soskice, 2001), as it enhances legitimacy, promotes clarity, and gives indication of state unity and purpose. Complementarity does not negate checks and balances where one arm of government is expected to work as a check and balance on the other. Rather, by ensuring that state functions are carried out effectively, institutional complementarity acts as another form of checks and balances.

6.2 Accountability

Africa has hosted a number of state capacity building initiatives. During the period, 1987–1997, the World Bank implemented at least 70 public service reforms projects designed to strengthen state capacities across Africa (World Bank, 1989). However, the results of these interventions were deplorable, with only about 29% of the project rated as satisfactory (Levy, 2007). As Levy observes, a principal reason for the poor performance of these projects was the erroneous assumption that overhauling the formal institutions of bureaucracy and providing financial support to agencies of government would almost definitely enhance state capacity. However, there is evidence that “public administrations are embedded in a complex, interdependent system” (Levy, 2007, p. 505–506).

In order to strengthen state capacity, there must be mechanisms to hold the political leaders accountable to the citizens. Designing novel ways to enforce political accountability is especially relevant for many African countries where there is high incidence of official corruption and other forms of irresponsibility on the part of political leaders (Adebanwi and Obadare, 2013). One way to enforce accountability is to adopt a bottom-up mechanism such as whistleblowing that incorporates local context and empowers citizens to take ownership of the corruption war (Okafor, et al., 2020; Okafor, et al., 2020). Another way is to implement monetary and fiscal policies that reduce the availability of cash. Researchers have found that both cash holdings and the ratio of currency in circulation have positive relationships with the level of corruption (Singh & Bhattacharya, 2017; Thakur & Kannadhasan, 2019). In addition, an efficient and impartial law enforcement system should be in place to try and punish corrupt officials. African states can also use naming-and-shaming strategy by publishing the names of public officers and corporate executives who engage in corruption and details pertaining to their offenses.

6.3 Empowerment of civil society groups

Related to the need for executive checks and balances is the need to create a vibrant nonstate force whose role would be to articulate the interests of its members (citizens) and work toward advancing those interests in a sustainable manner (Uphoff & Krishna, 2004). Strong civil society groups are expected to be independent of the state and are able to stand up against public corruption, executive recklessness and dereliction of duties on the part of state officials. In several African countries, the performance of civil society groups in holding the state accountable has been lackluster, at best (Aiyede, 2017). Weak civil society sector creates a vacuum in the governance architecture and somehow makes it convenient for many states to shirk their responsibility, especially in the provision of public services. However, it is acknowledged that some civil society group may focus on satisfying the selfish interests of their members, with little attention to the broader public good.1 In the push to create a more functional states, civil society groups that concentrate on expanding the public good should be encouraged.

6.4 Attitudinal change and value reorientation

In addition to formal institutions, cultures and norms affect the capacity of the state to actualize its mandate. Given the importance of nonstate forces in determining state's effectiveness, it is often important for states to consciously develop a program to generate political subjects who are not only willing to abide by state's legitimate rules and regulations, but are also willing to participate in civic duties as responsible citizens (Ansoms & Cioffo, 2016). The creation of political subjects is necessary because where a large number of citizens lack faith in the formal state institutions, dissent will be huge, tax evasion and avoidance will be high, and state-society relations will be generally tense. Any program designed to strengthen state capacity should also incorporate mechanisms for generating and expanding the population of political subjects who are responsible citizens willing to be subordinate to state rules, and at the same time active agents who utilize their own resources and networks to support the state to realize its objectives (Blundo & Le Meur, 2009). The actual process of developing these agents depends on each state's peculiarities, considering unique facilitators and constraints such as religion, ethnicity, and demography.

6.5 Engagement of Africans in the diaspora

It has long been recognized that African migrant populations abroad can be leveraged for development purposes in their origin states (Kaplan, 1997). Meyer et al. (1997) use the term “Diaspora option” to describe emerging policies to remotely mobilize intellectuals abroad to contribute to scientific and cultural programs at home. When the World Bank began to employ this term to describe its strategy to engage Diaspora, the focus shifted to the economic benefits to be derived from the Diaspora (World Bank, 2007). In Sub-Saharan Africa, the rise of the Diaspora option came at a time when the failure of the Washington Consensus led people to look for a new strategy toward building institutions capable of supporting liberalized markets (Pellerin & Mullings, 2013). It should be realized that the value of the Diaspora populations is not limited to narrowly defined science and technology, but often includes governance knowledge derived from their experience in host countries (Larner, 2007). Based on China's experience (Li, 2006), African countries should try to build into their Diaspora strategy an option to engage intellectuals abroad in improving governance institutions through consultations and appointment to leadership positions at home. While the Diaspora population can be a source of valuable expertise in African countries, some returning African nationals may equally embrace greed and corruption. Relatedly, some members of the Diaspora returning to Africa may fail to achieve social transformation due to their arrogance and high-handedness. We argue that the engagement of Africans in the Diaspora should be anchored on a framework that promotes mutual respect, and supports national development, and not self-aggrandizement.

6.6 Public-private partnership (P3)

African governments can use P3 to collaborate with the private sector to provide major infrastructure or service. Studies have found that P3 is associated with incremental economic and social benefits, efficiency in the delivery of critical infrastructure projects, experience, and shared risks (Carbonara & Pellegrino, 2014; Opara et al., 2017; Osei-Kyei & Chan, 2018). The capacity of African governments can be strengthened through more involvement in public-private partnerships. Collaboration with the private sector through P3 can enable African countries to fund expensive projects that would have been constrained by budgetary conditions.

In summary, this article proposes a model for strengthening the capacities of a state, particularly the weak states in Africa in Figure 5 above.

7 CONCLUSION

Despite divergence of opinions on the fine details and distinctions between the Washington Consensus and the Beijing model, at the very least, there is a convergence of evidence that both models have some merits and shortcomings. However, the success of each of the models depends on the presence of a functional state with efficient and inclusive institutions, including appropriate regulatory and enforcement mechanisms that create incentives for productive engagements of every agent in the society. One caveat should be noted regarding our earlier suggestion that a major difference between the two models is the scope of state activities. Our modified model of state capacity considers China to have “moderately strong state institutions”, but this treatment is rather simplistic and could be misleading. For Fukuyuma (2004), the strength of state institutions is not simply a measure of power but the ability to enforce rationalized policy and rule of law, otherwise a powerful state is just an authoritarian regime, and that type of regime can be abundant in Africa. Actually, it is the existence of authoritarian regimes that has made it possible, even fashionable for Africa's political leaders to convert state resources to private estates with ease.

Another take-way from this article is the need to separate adopting the Beijing Consensus as a development model from engaging China in economic activities. In other words, while this article adds to the literature by tracing the evolution of China's economic engagements with African countries versus the United States and the United Kingdom, and how these engagements have increased China's influence in Africa, our paper does not suggest that African countries have followed the Beijing model. As noted earlier, the incapacity of African governments to regulate FDI from China has ironically ignored a key element of the Beijing model, that is, the role of the state in regulating FDI to achieve technology transfer for the benefit of the receiving country (Kragelund, 2009). Importantly, Fukuyuma (2004) warns against relying on outside actors to strengthen state capacity, who tend to pursue policies that actually weaken political institutions of the focal state. Taking Fukuyuma's words in the African context, this article suggests that African countries should build government capacity from within. The framework for building Africa's state capacity, as Levy (2007) argues, must be expanded beyond the often simplistic and narrow focus on public service reforms and capacity building in the civil service, to incorporate the political dynamics, including altering the incentives of politicians to emphasize provision of public goods over selfish pecuniary considerations.

In addition, this article recommends conscious efforts to improve public affairs management in respective African countries through strengthening formal bureaucracy (such as developing merit-driven public service) and creating appropriate institutions to execute government policies and programs. In addition, it is important to empower the appropriate civil society groups to hold the government accountable, develop effective systems to fight corruption, and to engage responsible African professionals in the Diaspora to participate more actively in building state institutions in their home countries. Fortunately, hope appears greater today than when Fukuyuma first wrote his thesis, as there appear to be increasing demands for institutional transformation among African nations. This study concludes that the proposed strategies have the potential to improve the political, legal, administrative and bureaucratic architectures, and strengthen state capacity in Africa. However, our study has not assessed the efficacy of the strategies as determinants of state capacity. Future studies should provide a systematic quantitative assessment of these strategies as potential determinants of state capacity in developing countries.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographies

Kenneth Kalu is an Assistant Professor of International Business and member of the Advisory Council of the Canada–China Institute for Business & Development at the Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, Canada. He received his PhD from Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada. His research interests revolve around Africa's political economy. He is interested in examining the nature, evolution and interactions of economic and political institutions, and how these institutions shape the business environment and economic growth in Africa. He is also interested in examining the dynamics of China–Africa economic relations. His essays have appeared in several academic journals and books. His latest book is Foreign Aid and the Future of Africa (Palgrave Macmillan). He has held senior executive positions in the private and public sectors in Canada and overseas.

Oliver Nnamdi Okafor is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at the Ted Rogers School of Management at Ryerson University. He graduated with distinction from the IMT in Enugu, and holds an MBA in Banking and Finance from the University of Nigeria. He further obtained a second MBA in Global Energy Management and Sustainable Development, and a PhD in Management with a major in Accounting and Taxation, from the Haskayne School of Business, University of Calgary. He is a Chartered Professional Accountant, and Fellow Chartered Certified Accountant. He has held progressive positions in the banking industry, and worked for the First Bank of Nigeria Plc and the Royal Bank of Canada. He was also a federal tax auditor/trainer at Canada Revenue Agency, a contractor for CPA Canada, and a faculty at SAIT. He teaches the Advanced Financial Accounting & Disclosure at Ryerson University. His research is investigates sustainable development issues especially those relating to the United Nations goals. He also draws from his technical background in accounting and taxation to investigate aggressiveness in financial and tax reporting. He has published in referred journals such as the Canadian Tax Journal, Accounting Forum and the International Journal of Managerial Finance.

Xiaohua Lin is a Professor of International Business & Entrepreneurship and Director of the Canada-China Institute for Business & Development at of the Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, Canada. He received his PhD from the Oklahoma State University, USA. He was former Chair of the Academy of International Business' Canada Chapter and currently serves as Vice President (research) of the Canadian Council for Small Business & Entrepreneurship. His publications have appeared in journals such as Strategic Management Journal, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of World Business, Management International Review, and Journal of Business Ethics. His current research is focused on transnational entrepreneurship and innovation. He is the founder of the Canadian Entrepreneurship & Innovation Platform, a non-for-profit organization whose object is to promote entrepreneurship among the immigrant communities for the purpose of enhancing Canada's innovation and economic performance.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1 We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for this important point.