Racist connotations in xenophobic outbreaks: An Afrocentric evaluation

Abstract

The democratic jurisdiction in Africa meant to re-instil peace in the continent, unite her people and champion the philosophy of Ubuntu. It has endeavoured to eradicate the enduring legacies of colonial hegemony and assert a new identity distinguished by autonomous ideologies. Despite the dispensation of these efforts, African societies are still bedevilled by colonial fragments. This is evinced by the appalling racist undertones and xenophobic spells that are overbearing in Africa in the democratic wave. Today, the African continent is vexed by the increasing rate of xenophobic outbreaks that sometimes appear to be anchored in racist connotations. This, inter alia, menaces African humanism and social development in African societies. This qualitative paper has aimed to uproot racist precipitants in xenophobic attacks. It is theoretical in nature and evaluates the rapport between racism and xenophobia from an Afrocentric perspective. The study has found that the xenophobic sentiments in the present day are framed within the imaginings of race. It has illuminated racial identity as a catalyst for xenophobia.

1 INTRODUCTION

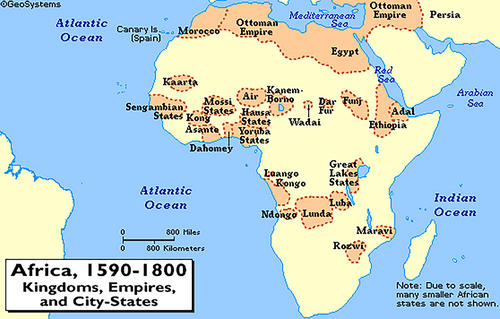

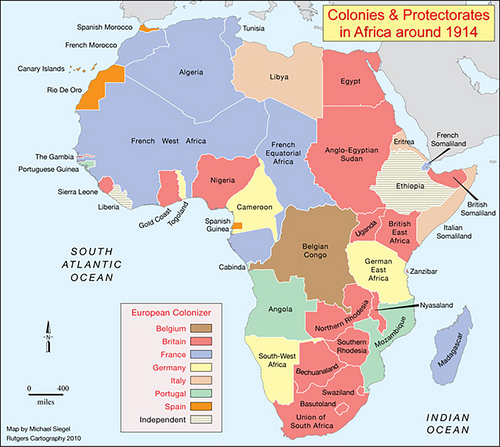

The African democratic forces sought to harmonise Africa and heal her people from the pain that colonialists had inflicted upon them during their administration. These liberation movements envisioned Africa as a peaceful, equal, and united society. This is braced by the vision of the African Union (AU): ‘An integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena’. The pilgrimage to utter rehabilitation and social transformation encountered colonial splinters that impeded the efforts to develop the African continent. These wreckages of colonialism include patterns of division such as racism and xenophobia. Tembo (2016, p. 102) notes that Africa reflects on the division between ‘the majority of life forms of the native (traditional societies) and that of so-called civilised society that colonialism had created’. The colonial brigades sought to eternise separation in the African continent. In the pre-colonial times, Africa was enshrined in oneness and it is the colonialists that introduced borders amongst the kingdoms (Betram et al., 2013). This point could be validated by the comparison between the pre-colonial and colonial maps of Africa illustrated below:

According to Figures 1 and 2, the advent of colonialists in the African continent marks the genesis of division in the continent. Figure 1 illustrates the state of Africa prior to colonisation where there were no fixed borders amongst the African kingdoms. Figure 2 on the other hand, depicts Africa subsequent to the colonial invasion. The European elites: Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain divided and shared African states amongst themselves to colonise. Thus, Figure 2 portrays a demarcated Africa. Therefore, Africa has undergone a major transition from being borderless to being bordered owing to the arrival of colonial forces in the continent.

Source: https://www.sahistory.org.za

The culture of division that the colonialists perpetuated in the African continent has kept on evolving until today despite the colonial government being subdued and dethroned by democratic movements many years ago. The African community cries out against the perturbing xenophobic epidemics that erupted predominantly in South Africa. This African society has been demonised by xenophobia more than other states in the continent. Scholars aver that it is because South Africa is a prodigy that inspires Africans from the neighbouring countries, hence, some of them depart to the country for greener pastures. For instance, Zajec (2019, p. 70) considers South Africa ‘as the Europe of Africa in terms of being the desired final destination of thousands of people’ whereas Nwaubani (2015) perceives it as a star of Africa. Furthermore, fellow brothers and sisters from the nearby countries experienced an agonising denunciation from the so-called ‘African star’. Tafira (2011, p. 114) recounts that ‘on 11 May 2008, violence against black African immigrants erupted in South Africa, starting in the Johannesburg township of Alexandra, and spreading to other areas of Gauteng. When the violence subsided, sixty-two people were dead, hundreds injured and maimed and thousands displaced’. On close examination, the researcher above singles out black foreign nationals as victims of xenophobic attacks. This engenders curiosity about the role of racial identity in the xenophobic ills. Thus, the motivation of the study emerges from the question: Is Xenophobia racially motivated? Many reports such as Tafira's (2011) recount point out black skin-toned foreign nationals and sometimes black skin-toned South Africans as victims of xenophobic attacks.

1.1 Theoretical and methodological interpretations

The theory of Afrocentricity, which sets out to assert and re-assert African identities is utilised to underpin the study. It is emboldened by the philosopher, Asante Molefe and it aims to, amongst others, perceive African issues ‘at hand from an African viewpoint; that we misunderstand Africa when we use viewpoints and terms other than that of the African to study Africa’ (Chawane, 2016, p. 78). Afrocentric epitomes such as the black identity endured stereotyping during the colonial period and the African democratic forces upon dethroning the colonial government sought to rehabilitate these Afrocentric identities. However, this study argues that the stereotypes against Afrocentricity manifest in xenophobic outbreaks today. This is evinced by racial motivations perceived in xenophobic attacks in the African context where Afrocentric canons such as the black identity are stigmatised (Montle, 2020; Solomon & Kosasa, 2013). Hence, Asante (1998) affirms that the Afrocentric method ‘seeks to uncover the masks behind the rhetoric of power, privilege, and position in order to establish how principal myths create place’. Furthermore, Scholars such as Neocosmos (2006), Nyamnjoh (2006), Solomon and Kosasa (2013) found that xenophobic attacks mostly victimised dark skin-toned people and therefore argued that xenophobia is actually hatred of too dark-skinned people. As Adams (2020) avers, a dark skin tone or the black identity is one of the essential characteristics of African identity. Therefore, the theory of Afrocentricity becomes relevant to undergird the study's criticism of xenophobic attacks in the African context.

This study employed a qualitative methodology, which comprises ‘collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research’ (Bandhari, 2020, p. 1). In qualitative research, sampling size plays an incidental role as it allows the researchers to select a sample size of their choice considering achieving the objectives of the phenomenon being studied. Thus far, qualitative research is mainly characterised by a purposively small sample for in-depth information purposes (Campbell et al., 2020). Accordingly, this study adopted a criterion purposive sampling to select a minimum of five datasets from empirical studies, complemented by mass media reports, with a belief that they are relevant to fulfil the aim of the study. A criterion purposive sampling is defined by Palinkas et al. (2015) as a strategy that offers relevant comprehensive data from potential participants or events within the study context.

The study further collected data through secondary sources, previous empirical studies, and mass media reports, which is a way of reusing the existing data to unveil some overlooked aspects about a certain phenomenon. According to Kumar (2014), secondary sources or data include earlier research, government publications, personal records, and mass media reports as existing data that is suitable to achieve the aim of the studied phenomenon. Subsequently, the study adopted supplementary secondary data analysis, which is a way of re-using the extracted existing data to address evolving issues either to investigate new questions or to verify the findings. In this context, the process of analysing data involves sorting, assessing, and discussing the previous findings in order to fulfil the objectives of the current study (Heaton, 2008). Hence, this study aimed to re-use the existing findings to unmask the racist connotations in the heart of xenophobic outbreaks in the African continent.

1.2 Racist underpinnings in xenophobic outbreaks

Xenophobia has and still rears its ugly head in the South African society. It has imperilled many foreign nationals to persecution. What becomes exceptionally disconcerting is that the xenophobic attacks ‘appear to have taken on a primarily racial form; it is directed at migrants, and especially black migrants, from elsewhere on the continent, as opposed to, for example, Europeans or Americans, who are, to a certain extent, practically welcomed with open arms’ (Solomon & Kosasa, 2013, p. 8). Moreover, Tafira (2011) also links xenophobia to racism and sustains that what is perceived as xenophobia is essentially racism. According to Dennis (2004), racism is the ‘idea that there is a direct correspondence between a group's values, behaviour and attitudes, and its physical features […] Racism is also a relatively new idea: its birth can be traced to the European colonisation of much of the world, the rise and development of European capitalism, and the development of the European and US slave trade’. On the other hand, Bolaffi (2003, p. 332) states that xenophobia is ‘an expression of perceived conflict between an ingroup and an outgroup and may manifest in suspicion by one of the other's activities, a desire to eliminate their presence, and fear of losing national, ethnic or racial identity’. The researchers above have defined racism and xenophobia respectively within the peripheries of ‘us’ (colonisers) and ‘them’ (colonised), and ‘them’ are the cursed and perennially marginalised group. It is the colonialists that fostered stereotypes against the black identity of the colonised Africans. Thus, several citizens of South Africa have experienced xenophobic attacks as a result of being mistaken to be foreign nationals because of their ‘too dark-skins’. Landau (2011:8) notes that ‘too-dark-skinned people, undocumented people and/or people belonging to a linguistic minority who are South African being harassed and arrested as if they were foreigners, and even occasionally being deported’. Furthermore, the colonial systems ‘did not distinguish between black South Africans and foreign Africans, all were interpellated and oppressed as foreigners and so united in the struggle against the system’ (Neocosmos, 2006). This noted, it is African foreigners that are stigmatised and perturbed by xenophobic undertones whereas European foreigners appear to be spared from the wrath. The word ‘African’ is dovetailed with ‘Black’ in a ‘state and popular discourse, so that national and racial categories have collapsed into one another’ (Solomon & Kosasa, 2013, p. 10).

My renunciation of the term xenophobia and subsequent adoption of the term New Racism is inspired mainly by the following propositions: xenophobia has been the term the media has used, juggled around and fed to their audiences; it is possible that the media themselves do not understand the racial nature of anti-immigrant attacks; commentators who have used the term may have done so unconsciously and inadvertently or for lack of a better term to describe anti-immigrant practices in post-apartheid South Africa. I assume that it may be incomprehensible to many people that racism can be a practice between people of the same skin colour. Furthermore, I suspect commentators, the media included, may fail to see the New Racism, as it has unfolded, as an unfortunate misconception. They may fall into the common trap of understanding the conundrum of racism as mostly biology-based. They have not come to see how people of the same skin colour, in this case black African immigrants and black South Africans, are and have over the years been transformed into racialised subjects and how they have come to perceive each other in the light of their racial subjectivities.

2 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The extracted findings from empirical studies about xenophobic attacks are to be sorted, assessed, and discussed underneath and the new findings will be derived according to the aim of the study. Table 1 below presents the existing claims which influence xenophobic attacks.

| Dataset no: Author(s) | Study title(s) | Claims for xenophobic outbreak |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1: Saleh (2015) | ‘Is it really xenophobia in South Africa or an Intentional Act of Prejudice?’ | Foreigners are the cause for increasing rates of unemployment and decline marriages. |

| Dataset 2: Linus (2019) | ‘Xenophobic attacks in South Africa spur reprisals across Africa’. | Competition for economic resources, foreigners as non-taxpayers. |

| Dataset 3: Mojisola (2019) | ‘Xenophobic attacks and its implication on human resource management’. | The effect of the apartheid system on the mind of the people, poor service delivery by government officials, competition for scarce economic resources is responsible for the attacks. |

| Dataset 4: Toh (2020) | ‘African Immigrant and the struggle against class, racism and xenophobic consequences in post-apartheid South Africa’. | Mindsets were influenced by the apartheid policy, which was based on hatred, class, race, and violence. |

| Dataset 5: Montle and Mogoboya (2020) | ‘(Re) examining the need for Ubuntu as an antidote to xenophobia in South Africa through a glimpse into Mpe's Welcome to Our Hillbrow’. | Foreign nationals are associated with corrupt activities such as fraud, bribery, extortion, illegal trade, and embezzlement. |

2.1 Dataset 1: Job security

The table above indicates the existing claims which cause xenophobic outbreaks. Starting with dataset 1, the study of Saleh (2015) focusing on xenophobia in South Africa indicates that the underlying reasons for xenophobic attacks are based on the increasing rates of unemployment and declining marriages. The foreigners in this context are alleged to be the reasons why many South African men are unemployed and unmarried. The argument on these allegations is that the foreigners came to South Africa to steal their jobs and that leaves South African men bankrupt and unable to marry since they cannot afford lobola prices due to their unemployment. Therefore, such reasons developed hatred towards foreign nationals which later burst out as xenophobic attacks.

The findings above show that job security is a frustrating issue that fuel hatred towards foreign nationals. Solomon and Kosasa (2013, p. 11) reflected on this excerpt: ‘The foreigners came [to South Africa], with nothing […] in the sense [that] they've got no papers, nothing, nothing, they jump the border, […] go to their brothers, get money from him, they go to the informal areas, get a small little shop, cut the prices, […] and what happens: creates competition. […] So they have affected our business. They have taken over the business from the local people’. There seems to be a mounting concern in the South African society that foreign nationals are prioritised for jobs if not steal them. This is one of the South Africans' cries against foreign nationals.

Colonialism divided the world in two: the centre, which is occupied by Europeans, and the periphery, which is occupied by non-Europeans. This division institutionalised poverty amongst the colonised to maintain the supremacist status of the coloniser and the colonial status of the colonised as non-beings. Colonial apartheid, following the colonial epistemological foundation(s) and justification(s) of the centre imposing itself on the periphery, strived to make black people go through social death.

2.2 Dataset 2: Witchcraft

The second dataset is based on Linus' (2019) investigation about the xenophobic attacks in South Africa. The findings indicate that the competition for economic resources is an underlying reason for South Africans to develop hatred towards foreigners. For this reason, South Africans claim their business became unsuccessful ever since the arrival of foreign nationals. They further stress that the foreigners have a tendency of selling goods at lower prices because they are free from paying tax unlike them, South Africans. This means that the businesses owned by South Africans are at risk to close since they cannot afford to lower their prices to such an extent as they are bound to tax. Circumstances such as this brought further allegations that these foreign nationals use muthi for their businesses to succeed and outrun the ones owned by South Africans.

Based on the above quote, ‘this is not to say that people always explicitly speak of foreigners as witches. Some of them do, like Thandile. But the more important point is that people conceptualize and evaluate foreigners and witches as morally analogous types of persons—as mysterious, anti-social agents that disable productive and reproductive processes’ (Hickel, 2014, p. 108). Furthermore, there has been a trending means of becoming wealthy with the use of a snake called a mamlambo. It is postulated that the snake brings the owner a lot of money provided that he or she performs human sacrifices for it. Foreign nationals are identified as pioneers of this witchcraft wealth.When the makwerekwere come here we no longer develop, and our children no longer progress. If we have reached 80 percent then we fall back to 10 or 0 percent. For example, if I have a shop and a foreigner comes here and sets up a shop nearby, then his shop will succeed and my shop will fail. They will go up and we will go down. The only way to explain this is that they are using something . . . that they are using ubuthakathi. You see how they come here, they are so poor, they come from a poor country and they come across the border with nothing but a passport. There is no way that they can become rich after only three years or so here! There must be something behind it . . . they are using ubuthakathi. There is no other way to explain it.

Hickel (2014, p. 108) claims that a local prophet explained to him how foreigners use mamlambo to become rich and said that the immigrants sell the snakes at R9000, and also utilise a special muthi to steal the blessings of others. He said the prophet commented that the muthi works like a cell phone camera as it captures other people's blessings. These are some of the assumptions that motivate xenophobic attacks. The alleged foreign nationals' expertise in witchcraft are said to aid them to outmanoeuvre South Africans in workplaces, hence, employers prefer them: ‘immigrants always seem to outcompete South Africans in the informal economy. In a separate conversation, Thandile told me that this is mostly because foreigners use umuthi, the medicinal substances used by witches, to make their businesses succeed’ (Hickel, 2014, p. 110).

2.3 Dataset 3: Competition for economic resources

Dataset 3, the findings of Mojisola (2019) point out that the issue of xenophobia is deeper than how it is displayed. The hatred is not about the foreigners to depart but also the reflection of wounds caused by the apartheid government which left many scars in the hearts of South Africans. The scars left the citizens with the spirit of violence and hatred that keeps them to be ready for violence, hence poor service delivery by government officials and competition for scarce economic resources fuel attacks. In other words, the apartheid mindset makes South Africans look for someone to blame whenever they face challenges such as poor service delivery as well as missing opportunities as they were previously disadvantaged. Although they are regarded as wounded citizens, there seems to be a tendency to scapegoat foreign nationals. This validates Madue's (2015) idea about the xenophobic attacks which continue to break out in South Africa whenever the citizens get frustrated due to the slow pace of service delivery. This is a call for revision of policies related to human resource management to ensure fairness.

2.4 Dataset 4: Fraudulent marriages

The Nigerian-born University of Fort Hare academic who lied about his marital status to secure South African citizenship, has quit the institution. Edwin Ijeoma, a professor in the department of public administration was placed on precautionary suspension in October over allegations he was complicit in fraud committed against the university. The department of home affairs revoked his SA citizenship in 2009 after discovering Ijeoma was legally married in Nigeria when, as a doctoral student at Tukkies, he married a local woman and obtained naturalization based on that event. Over a decade later, Ijeoma's options ran out when the Bhisho high court confirmed the DHA acted correctly in revoking his citizenship.

2.5 Dataset 5: Drug smuggling

According to dataset 5, Montle and Mogoboya (2020) indicate the lens through which South African citizens view foreign nationals in this country. The results show that foreigners suffer discrimination of which they are associated with corrupt activities such as fraud, bribery, extortion, illegal trade, and embezzlement. The illegal trade claims towards foreigners are extended as follows: The future of South Africa is menaced by drug abuse. Many lives, especially the youth of the country are victimised by different drug crazes such as Bluetooth, Nyaope, Cocaine, Mercedes and Mandrax. These drugs are addictive and often incentivise users to engage in criminal activities that disturb communities. To deracinate this problem, South Africans set to dismantle the agents of drug abuse and foreign nationals were pointed out as one of the proxies. Ndaba, the chairperson of Sisonke's Forum said, ‘If ever they are serious about this issue, we can even show them schools. The kids are not problematic. The only thing that is problematic is drugs and these foreign nationals pushing drugs to our nation’ (Mail & Guardian, 13 September 2019).

Clearly, immigrants are not only stereotyped in the media, but they are also branded as potential criminals, drug smugglers and murderers by politicians and unreliable figures are bandied around Parliament. The government has also been criticised for its legislation and its focus on reducing the number of immigrants through repressive measures (Palmary, 2004). The Immigration Act 2002, for example, gave police and immigration officers powers to stop anyone and ask them to prove their immigration status.

2.6 Making sense of xenophobic attack as new findings

The African democratic forces, upon taking reins, abolished the colonial policies that upheld separation in the continent. This meant that Africans are unrestricted to unite and decolonise the continent. Thus, Solomon and Kosasa (2013, p. 10) aver that ‘the end of apartheid meant the waiving of international borders and for South Africans to come into contact with people previously unknown’. However, the new findings derived from the presented datasets indicate that colonial attitudes seem to have imbibed many African natives who sabotaged the African reunion and carried out attacks against their fellow brothers and sisters from the neighbouring countries. Tafira (2011) calls this phenomenon new racism where racism is meted out by black people upon their black foreign nationals whom they perceive as a subsidiary. This racially selective xenophobia sometimes referred to as new racism by scholars such as Tafira (2011) undermines the philosophy of Ubuntu, which the democratic forces aimed to re-establish Africa based on. The xenophobic sentiments have proven to impair the socio-economic transformation of Africa and uphold the colonial heritage of division in the continent. Montle and Mogoboya (2020, p. 75) assert that ‘the foregoing causes of xenophobia in South Africa expose the extent to which xenophobic problem poses a menace to Africa's humaneness’. These xenophobic attacks insinuate that success is more valued than unity and harmony. Thus, the government should show sincerity and goodwill towards ending this violence of xenophobic attacks by raising awareness about Ubuntu; revisiting human rights management policies to ease the economic resources competitions, and revisiting South African's foreign policies to protect the rights of foreigners and ensure security.

3 CONCLUSION

This paper has endeavoured to discuss the role of racial identity in the xenophobic worries that invaded the African continent, particularly the South African society where acts of xenophobia have intensified tremendously. The findings from the xenophobic have suggested that there is a crucial rapport between race and xenophobia as people who subscribe to the black identity are found to be the victims of xenophobia even though some of them are not foreign nationals but citizens of the country. A variety of scholars and activists have risen to ask why xenophobia seems to menace only black foreigners whereas there are also white foreigners. Scholars such as Neocosmos (2006), Nyamnjoh (2006), Solomon and Kosasa (2013), Montle and Mogoboya (2020) point out the enduring colonial perceptions as the hidden perpetrators. Montle and Mogoboya (2020) assert that many Africans in the post-independent progressively adopt the colonial tactics of alienating black people and abuse them, especially the poverty-stricken masses. This is buttressed by the racist undertones, the brainchild of colonialism that influences the degree of xenophobia in the present day. This noted, it is important for Africans to attempt all efforts to re-essentialise Ubuntu and the value of unity in the African continent. This recommendation would remind Africans about the painful struggles they endured for peace, unity, and equality, hence, cherish Ubuntu and dismantle racial motivations.

Biography

Edward Montle is a PhD candidate and lecturer at University of Limpopo, Department of Languages. His research interests include African literature in English, Identity, Literary theory and post-colonial issues in the African context. He has published several journal articles in DHET accredited journals and also presented papers in local and international conferences.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.