Perceived severity, fear of retaliation, and suspect report intention of general public during COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated moderation analysis

Abstract

Management of COVID-19 largely depends on the reporting of suspected or confirmed positive cases. This study examined public's suspect report intention during COVID-19 using and extending the theory of planned behavior by adding two incident-specific variables such as perceived severity of COVID-19 and fear of retaliation. Direct association of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control with suspect report intention and moderating role of perceived severity of COVID-19 and fear of retaliation were probed. This study also investigated whether the moderation of perceived severity of COVID-19 (primary moderator) varies with different level of fear of retaliation (secondary moderator) using moderated moderation analysis. Analyzing data collected from 554 Indian citizens provides evidence that attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control were positively associated with suspect report intention. Perceived severity of COVID-19 and fear of retaliation negatively moderated such associations. When fear of retaliation was high, high perceived severity of COVID-19 did not positively moderate the association of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control with suspect report intention. Perceived behavioral control was the most potent facilitator and fear of retaliation was the strongest inhibitor of suspect report intention. Understanding people's suspect report intention can assist in implementing awareness programs to encourage suspect report intention and stop the community spread of COVID-19.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has sustained for over a year now and new lethal strains are emerging across many countries (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Therefore, researchers recommend learning how to live with this virus (Giri et al., 2021) even after vaccination drives. Governments across the globe have been working relentlessly to flatten the COVID-19 curve through different containment and mitigation strategies such as lockdown and shutdown and implementing a variety of non-pharmaceutical interventions (Brauner et al., 2021). Effectiveness of such strategies and interventions depends on the responsible behavior (Campos-Mercade et al., 2021; Everett et al., 2020) or the compliance behavior (Clark et al., 2020) of the citizens. Along with personal hygiene and social distancing, citizens must play an active role in early reporting and isolation of suspected or confirmed positive cases (WHO, 2020a). To arrest contagion, authorities issued guidelines to the general public to quickly report themselves or others in case of suspected symptoms or contact of a confirmed case, and also voluntarily assist the administration in case finding and contact tracing (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2020a; WHO, 2020b). However, there were large scale violations (Shareef et al., 2021) and underreporting (Biswas et al., 2020) due to the intense fear, uncertainty, and stigma associated with the disease (Arora et al., 2020). During the pandemic, it was also found that socially responsible people considered it as their civic duty and self-reported, −tested, and -quarantined as well as reported about the presence of a person suspected with COVID-19 symptoms or violating COVID-19 regulations in their locality (Kwan, 2021; Mitchell, 2020). Though self-reporting behavior got applauded and is well-researched (Travaglino & Moon, 2021; Wu et al., 2020) public's suspect reporting intention or behavior got little attention. This paper examines the suspect report intention (SRI) of general public during COVID-19 pandemic using an extended theory of planned behavior (TPB).

The novelty of COVID-19 created confusion, fear, and anxiety (Arora et al., 2020) and psychological distress (Alat et al., 2021) among people. The fear of getting infected by someone has let to discrimination and stigma toward people with COVID-19 symptoms (Bagcchi, 2020). People belonging to infected locations or hotspots, specific communities, occupations, and having recent travel history to countries, states, places with large number of cases are stigmatized (Ganguly et al., 2020). Such public stigmatization can potentially thwart early detection, isolation, and treatment efforts (Barrett & Brown, 2008). To avoid stigmatization, people fear seeking health care and conceal illness when approached (O'Connor & Evans, 2020; Teo et al., 2020). During pandemic, people do a cost–benefit analysis. They weigh the benefit of reporting about their symptoms or about their travel history to health administrators against the cost of being stigmatized in the community whether or not they turn to be positive. If the cost is more, then people refrain from reporting. People also do not self-report about their symptoms due to their unrealistic optimism. It was found during the COVID-19 pandemic that people believed others, not themselves, to be the victims of COVID-19 (Dolinski et al., 2020; T. Park et al., 2021). When people believe that they or their family members are safe and have less chance of getting infected, then they may not report. Hiding COVID-19 symptoms and concealing travel history can lead to community spread (O'Connor & Evans, 2020; WHO, 2020c) and hence has been declared as criminal acts in some parts of the world (Sharma, 2020; The National, 2020; The New Indian Express, 2020b).

When people suspected with COVID-19 symptoms, do not self-report to get tested, quarantined, and treated, general public's reporting about those people to the health administration is crucial to all the subsequent pandemic mitigation measures. Only mass reporting of suspected cases (both self and by others) can ease the Government's effort to identify, isolate, treat, and contain the transmission of COVID-19 infection. Governments across the globe have started online portals and emergency helplines to facilitate reporting of non-compliance and violation of pandemic mitigation guidelines (Kwan, 2021). The Government of India also started a national COVID-19 helpline (1075) for reporting of suspected COVID-19 cases by grass root level health workers, private institutions, and general public (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2020a, 2020b). In populous countries like India, it becomes difficult for the Government to reach each citizen and mobilize mass testing. Therefore, the Government of India declared the world's first ever biggest nationwide lockdown of 21 days on March 24, 2020 (Chandrashekhar, 2020) which was later extended at different phases till May 17, 2020. The declaration of lockdown was followed by the exodus of migrant laborers to their hometown (Ganguly et al., 2020) which increased the risk of COVID-19 spread during travel among co-passengers and after reaching home among the native communities (Maji et al., 2020). After the exodus, COVID-19 cases spiked in India especially in rural areas (Gettleman et al., 2021; Ghoshal & Jadhav, 2020; Mullick, 2020). COVID-19 cases also increased after India allowed expatriates and students to return home (Ganguly et al., 2020). Anticipating the spread of the virus, the Government of India deployed the grass root level health workers to create and spread awareness among people to report about their COVID-19 symptoms as well as to report about other persons having symptoms or recent travel history in their vicinity (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2020a).

There are numerous studies on the health-protective behavior during this pandemic which explained public's compliance to mitigation measures and self-reporting behavior with the help of health belief model (Faasse & Newby, 2020; Jose et al., 2021; Riiser et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2020; Zickfeld et al., 2020) and protection motivation theory (Al-Rasheed, 2020; Kowalski & Black, 2021; Prasetyo et al., 2020; Rad et al., 2021). Harris and Guten (1979) define health-protective behavior as any behavior by people, regardless of their perceived or actual health status, to protect, promote, or maintain their health, whether or not such behavior is objectively effective toward that end. Hence, people's reporting about other people who are suspected with COVID-19 symptoms or who do not voluntarily report themselves can be considered as a health-protective behavior. When people sense the possible presence of any person suspected with any or all the symptoms of COVID-19, they may report such person to the health administration to protect themselves and their family members from the infection. Suspect report behavior is difficult to observe, because the Government never reveals the identity of the reporters and people may not voluntarily disclose. Hence, SRI can be considered as a proxy of suspect report behavior. SRI can be defined as the intention of the general public to report about the presence of people in their vicinity who are suspected of having the symptoms of COVID-19 and have concealed their health status and travel history after returning from an infected place. But people's intention to report about people suspected with COVID-19 symptoms as a health-protective behavior has not received any attention in the literature and thus, it is imperative to understand SRI. Understanding SRI can help develop strategies to encourage reporting of suspected cases and assist health administrators in curbing the infection and providing prompt treatment to the infected people.

1.1 Understanding SRI through the TPB

SRI is similar as unethical behavior reporting intention, whistleblowing intention, and crime report intention. All such intentions have been well predicted using the TPB (Carpenter & Reimers, 2005; Harvey, 2009; Keller & Miller, 2015; H. Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009). Intention is the subjective probability that an individual will engage in the behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). According to TPB, individual's intention to perform or not to perform a behavior is the proximal determinant of human behavior (Ajzen, 1991, 2020). Strong intention is more likely to translate into actual performance of the behavior. Intention is influenced by three major factors: attitude (a favorable or unfavorable appraisal of an action), subjective norm (the perceived social pressure to do or not do it), and perceived behavioral control (PBC; the perceived ability to see to do so). The substantial correlation between individuals' intentions and their subsequent behavior (Ajzen, 2011) allow researchers to measure behavioral intentions rather than actual behavior. TPB has also been used extensively during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand public's prevention measure compliance intention (A. K. Das et al., 2021; Prasetyo et al., 2020), panic buying intention (Lehberger et al., 2021), and travel intention (Li, Nguyen, et al., 2020). Hence, TPB is deemed to be the most suitable theory to explain public's SRI.

Attitude refers to the favorable or unfavorable appraisal of a behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Attitude toward a behavior comes from the belief in and subjective importance of the consequences of such a behavior (Ajzen, 2020). People's attitude toward suspect reporting is the product of their belief and their subjective evaluation about the consequences of reporting. The consequences of suspect reporting might include preventing spread of disease in the locality, saving the life of the suspected person, protecting public health, and moral satisfaction, etc. Such positive consequences of suspect reporting might drive people to report about a COVID-19 suspect. The more favorable appraisal of the consequences of reporting about a hiding COVID-19 suspect, the more likely it is that the person will intend to report. Hence, it is expected that:

H1.Attitude will be positively associated with SRI.

Subjective norm is the perceived social pressure from significant referents (e.g., friends, family members, and peers) to perform or not to perform a behavior (Ajzen, 1991). This pressure comes from the acceptance and approval of behavior by the significant others (Ajzen, 2020). Likelihood of a person's SRI depends on the extent to which he/she believes that the behavior of reporting is expected and acceptable by the society (Ajzen, 1991). If people believe that their family members, friends, neighbors, and other societal members approve the reporting of a COVID-19 suspect to the health administration, then they feel motivated to report. Hence,

H2.Subjective norm will be positively associated with SRI.

PBC refers to person's perceived ease or difficulty and anticipated impediments in performing the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The behavior or intention depends on people's perceived capability, controllability, and self-efficacy to perform the behavior. PBC is determined by previous experience of the behavior and also influenced by similar experiences of friends, family members or others (Ajzen, 1991). In this case, people may not have any prior experience of suspect reporting, but their intention to report might be influenced by resources and the opportunity to perform a behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009). First, the ease of contacting the health administrator and reporting anonymously is important for people. If people are not aware of the available mediums like national helpline, online portals etc., they may not intend to report. Second, if they feel that they can report without getting involved into any hassle with the administration or the person getting reported, then they will intend to report. Third, if they come to know about people in their locality or elsewhere are reporting, then they may show intention to report. If people believe that they can report with the available convenient means, then they will show SRI. The greater the PBC, the stronger is the people's intention to report a suspect. Hence,

H3.PBC will be positively associated with SRI.

1.2 Understanding SRI through an extended model of TPB

Existing research on crime report intention reveals that there are three categories of predictors of report intention: individual-specific, event- or incident-specific, and environment-specific variables (Bennett & Wiegand, 1994). The factors of TPB slightly follow this categorization, as attitude and PBC are individual-specific and social norm is environment-specific (Keller & Miller, 2015). TPB does not include any incident-specific variables. According to Armitage and Conner (2001), inclusion of domain specific factors can improve the power of the TPB framework to predict intention. However, there are two such incident-specific variables that might influence suspect reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those are perceived severity of COVID-19 (PSC) and fear of retaliation (FR).

Perceived severity refers to an individual's subjective evaluation of the pandemic's seriousness and is one of the greatest predictors of health-protective behavior (Weinstein, 2000). According to the health belief model (Rosenstock, 1974) people who consider a health concern to be serious are more likely to participate in behaviors that will prevent the health problem from occurring or reduce its severity. Perceived severity encompasses evaluations of the health consequences of a disease as well as the broader social consequences. PSC has also been widely studied during COVID-19 pandemic (Li, Yang, et al., 2020). A high perceived severity of a disease engenders proactive health-protective behaviors (Li, Yang, et al., 2020; Weinstein, 2000). PSC also reduces behavioral intention (S. S. Das & Tiwari, 2020) because too much worry and anxiety act against health-protective behavior (Imbriano et al., 2021; M-Amen et al., 2021).

FR refers to an individual's belief that reporting a person suspected with COVID-19 symptoms would result in negative repercussions from the person or his or her family members. Retaliation can take any form including, loss of social relationships, verbal abuse, physical violence, social ostracism against individuals, their family or both. Retaliation is natural and grounded on the provocation and aggression principle (Barlett et al., 2019; Lawrence & Hutchinson, 2012). People who get reported, consider their reporting to the health administration as an act of provocation. They feel such provocation is unjustified and harmful to their social image. Hence, they retaliate against the reporter or the provocateur. Retaliation was not very uncommon in India during the first phase of COVID-19. There were instances in which suspect reporters have been verbally and physically abused leading to the death of the reporter (Tewary, 2020; The New Indian Express, 2020a). There was also widespread violence and stigmatization against healthcare workers (The Lancet, 2020) which can deter common people from reporting about suspected cases.

According to the protection motivation theory, human beings perceive threat of certain diseases and/or behaviors (Rogers, 1975) which moderates their health-protective behavior. The protection motivation theory is developed on the premise of fear appeals (Milne et al., 2000). Fear appeals activate our threat appraisal tendencies in any situation and consequently influence our decision outcomes (Lerner & Keltner, 2001). When health threatening situations elicit fear, people engage in strategies to reduce their fear and in doing so they may avoid other strategies that will directly reduce the danger itself (Leventhal, 1970). During COVID-19 pandemic, people perceive threats from two fronts. First, COVID-19 pose a threat to the health of self and the loved ones, has high mortality rate, and threat to the social order (PSC). Second, people suspected with COVID-19 symptoms also pose threats in the form of possible aggression if reported to the health administrator (FR). When posed with threats from two fronts, people trade-off between both the threats and act against the threat which is perceived to be more severe and imminent. If COVID-19 infection is very severe and spreading rapidly in the locality, then people might report about people who conceal symptoms and travel history to help the administration. Hence, it is expected that:

H4.PSC will positively moderate the (a) attitude-SRI, (b) subjective norm-SRI, (c) PBC-SRI relationships.

Given the uncertainties due to the asymptomatic cases and faster human to human contagion, the intention to report any possible suspect (mostly coming from the infected area) is probably high, but the fear of being retaliated is equally a deterrent. Contrarily, if people suspected with COVID-19 symptoms are more powerful socially and pose more threat than COVID-19, then people might not report about them. In an act of retaliation, news of murder for reporting returnee to the authorities have surfaced in many places in India (Tewary, 2020; The New Indian Express, 2020a). In India, the society is basically collectivistic with more cohesiveness, interdependence, and coexistence, which might also prevent reporting by an individual fearing the loss of relationship, being socially stigmatized, and ostracized. Hence,

H5.FR will negatively moderate the (a) attitude-SRI, (b) subjective norm-SRI, (c) PBC-SRI relationships.

PSC and FR do not exist in a vacuum. With the increase in the threat perception of the pandemic, the overestimation of health risks (Taylor et al., 2020), and stigmatization of people who are considered to be the source of infection (Bagcchi, 2020) increases. People who are afraid of being stigmatized are compelled to retaliate against individuals who have or are expected to harm their image (Smart Richman & Leary, 2009). It is quite plausible to believe that PSC will moderate the link between the components of TPB (attitude, subjective norm, and PBC) and SRI differently at different levels of FR. If the suspected person turns to be a confirmed case, might infect more people in the vicinity if not reported on time. In such cases, if people perceive low FR, for example strained social relationships compared to high FR of physical harm, then they might forego their relationship with the suspected person and might report him or her to the health administrator. Maybe people who perceive COVID-19 as more severe will have high SRI when they have low fear of retaliation. Hence, it is expected that:

H6.At higher levels of FR, the moderation effect of the PSC on the (a) attitude-SRI, (b) subjective norm-SRI, (c) PBC-SRI relationships will lessen.

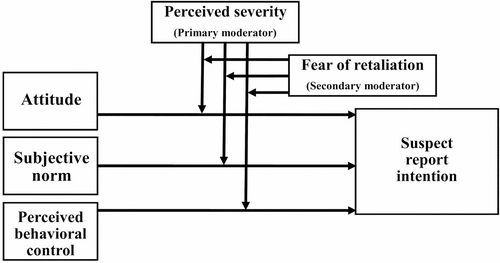

Extant literature has examined various health-protective behavior such as public's compliance to mitigation measures and self-reporting behavior during COVID-19 and other pandemics (Faasse & Newby, 2020; Kowalski & Black, 2021; Prasetyo et al., 2020; Riiser et al., 2020; Tong et al., 2020; Zickfeld et al., 2020). But people's SRI during COVID-19 or any other pandemic as a health-protective behavior has not drawn the attention of researchers. What facilitate and inhibit people from reporting about people with potential to spread a disease remains unexplored. The current study attempted to understand public's SRI using an extended model of TPB. TPB model was extended by adding two COVID-19 incident-specific variables such as PSC and FR. Understanding SRI is important in promoting SRI and behavior during any infectious disease outbreak. Understanding of SRI which could ultimately help health administrators for identifying, tracing, isolating, and treating people suspected with symptoms of infectious diseases. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of the study.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Participants included 554 self-selected Indian citizens who were above 18 years of age and residing in the six most COVID affected states (during the time of data collection) in India namely, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Telangana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh were invited to participate in the survey. The participants were predominantly male (72%), single (71.8%), post-graduates (35%), and were students (51.6%). Their age ranged from 18 to 62 years (M = 28, SD = 8.15) and their family size ranged from 2 to 8 members (M = 4.5, SD = 1.15). Table 1 shows the sociodemographic profile of the participants.

| Characteristics | N | % | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 399 | 72 | ||||

| Female | 155 | 28 | ||||

| Age | 28 | 8.15 | 18 | 62 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 398 | 71.8 | ||||

| Married | 152 | 27.4 | ||||

| Divorced | 4 | 0.7 | ||||

| Family size | 4.5 | 1.15 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Highest qualification | ||||||

| High school | 4 | 0.7 | ||||

| Intermediate | 40 | 7.2 | ||||

| Graduate | 189 | 34.1 | ||||

| Post-graduate | 194 | 35.0 | ||||

| Post-graduate and above | 108 | 19.5 | ||||

| Profession | ||||||

| Student | 286 | 51.6 | ||||

| Unemployed | 37 | 6.7 | ||||

| Employed | 183 | 33 | ||||

| Self-employed | 25 | 4.5 | ||||

| Homemaker | 16 | 2.9 | ||||

| Retired | 7 | 1.3 |

- Note: N = 554.

2.2 Measures

All the variables of the TPB were measured using 12 items (see Table A1) adapted from the Hays (2013). Attitude, PBC, subjective norm, and SRI, were measured using three items each. PSC was measured with three items (severity of infection, mortality, and the negative impact on social order) adapted from Li, Yang, et al. (2020). FR was measured with three items developed for this study based on the prior works on whistleblowing and crime report intention. The response descriptors of all the items were on seven-point semantic differential scale. Participants were also requested to provide information about their gender, age, highest qualification, profession, and marital status.

2.3 Procedure

Data was collected during the second and third week of the first nationwide lockdown (March 30, 2020 to April 12, 2020). This time period was selected, because around this time, the number of positive cases increased substantially in India (The Hindu, 2020). The survey was in English and administered using Google Form. Authors posted the survey link on different social networking websites inviting participations from general public, members of authors' alumni network, and student groups. The survey link was also shared among the authors' personal connections via social media platforms such as WhatsApp. The participants self-selected themselves to participate and their informed consent was sought. The convenience sampling method was used. Nationwide lockdown also suited to and justified online mode of data collection. The Institutional Ethics Review Board (IERB) of University of Allahabad, Prayagraj, India approved the study (IERB ID: PSY-P-21-003).

3 RESULTS

First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to establish the validity and reliability of all the constructs. The CFA model had acceptable fit indices (X2/df = 4.67, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.08). Descriptive statistics, inter-correlations, reliability, and validity of all constructs are presented in Table 2. All the constructs showed acceptable composite reliability > 0.70 and acceptable convergent validity (average variance extracted) > 0.50 (Hair Jr. et al., 2017). Internal consistency reliability of the variables were assessed using the McDonald's Omega (ω) instead of Cronbach's alpha. Cronbach's alpha is sensitive to number of items and does not assume tau-equivalence hence McDonald's ω is a better indicator of internal consistency than Cronbach's alpha (Hayes & Coutts, 2020). Discriminant validity of the variables were established by both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) criterion (Henseler et al., 2015). The square roots of the average variance extracted of each construct are greater than their respective off-diagonal elements establishing the discriminant validity of the constructs. The HTMT ratio of correlations were below the most conservative threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), suggesting discriminant validity of all the variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitude | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| 2. Subjective norm | 0.41*** | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.51 |

| 3. Perceived behavioral control | 0.72*** | 0.35*** | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.84 |

| 4. Perceived severity of COVID-19 | 0.84*** | 0.39*** | 0.74*** | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.79 |

| 5. Fear of retaliation | −0.43*** | −0.19*** | −0.33*** | −0.41*** | 0.86 | 0.50 |

| 6. Suspect report intention | 0.84*** | 0.46*** | 0.71*** | 0.82*** | −0.47*** | 0.86 |

| Mean | 5.63 | 4.97 | 5.55 | 5.70 | 3.24 | 5.82 |

| Standard deviation | 1.30 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.64 | 1.35 |

| McDonald's ω | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| Composite reliability | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| Average variance extracted | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

- Note: Bold-faced values represent the square root of each factor's AVE. HTMT ratio of correlations in the upper diagonal.

- *** p < 0.001.

Then, three moderated moderation models were tested using the Model 3 of the Hayes's PROCESS macro v. 3.5; Hayes, 2017) for IBM SPSS (v. 26). Bootstrap resampling (2000 samples) was used to estimate 95% confidence intervals. In this model, PSC was the primary moderator (M), and FR was the secondary moderator (W). All variables were standardized to have a mean of 0 prior to the analyses. Table 3 shows the results of the first moderated moderation model. This model shows the three-way interactions among attitude, PSC, and FR on SRI. Supporting hypothesis H1, attitude was positively associated with SRI. The interaction of attitude and PSC and the interaction of attitude and FR negatively predicted SRI. Hence, H4a was not supported whereas H5a was supported. The unconditional interaction among attitude, PSC, and FR was significant (b = 0.09, p = 0.003). Hence, H6a was supported.

| Paths | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT→SRI | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.65 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.22 | H1 supported |

| AT × PSC→SRI | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.59 | 0.002 | −0.18 | −0.05 | H4a not supported |

| AT × FR→SRI | −0.08 | 0.03 | −2.87 | 0.004 | −0.14 | −0.03 | H5a supported |

| AT × PSC × FR→SRI | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.00 | 0.003 | 0.03 | 0.14 | H6a supported |

The conditional effects of attitude and PSC interaction on SRI at different values of FR are showed in Figure 2. PSC moderates the relationship between attitude and SRI only when the FR is low (−0.76) and medium (−0.35). When the FR is highest (1.68), PSC does not moderate the attitude and SRI relationship (p = 0.41).

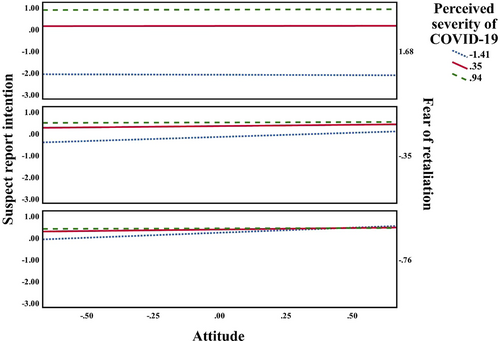

Table 4 shows the results of the second moderated moderation model. This model shows the three-way interactions among subjective norm, PSC, and FR on SRI. Subjective norm was positively associated with SRI supporting hypothesis H2. The interaction of subjective norm and PSC and the interaction of subjective norm and FR negatively predicted SRI. Hence, H4b was not supported and H5b was supported. The unconditional interaction among subjective norm, PSC, and FR was significant (b = 0.10, p = 0.001). Hence, H6b was supported.

| Paths | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN→SRI | 0.15 | 0.02 | 6.91 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.19 | H2 supported |

| SN × PSC→SRI | −0.18 | 0.02 | −8.09 | 0.001 | −0.23 | −0.14 | H4b not supported |

| SN × FR→SRI | −0.17 | 0.02 | −7.27 | 0.001 | −0.21 | −0.12 | H5b supported |

| SN × PSC × FR→SRI | 0.10 | 0.03 | 3.82 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.15 | H6b supported |

The conditional effects of subjective norm and PSC interaction on SRI at different values of FR are showed in Figure 3. PSC moderates the relationship between subjective norm and SRI only when the FR is low (−0.76) and medium (−0.35). When the FR is highest (1.68), PSC does not moderate the subjective norm and SRI relationship (p = 0.64).

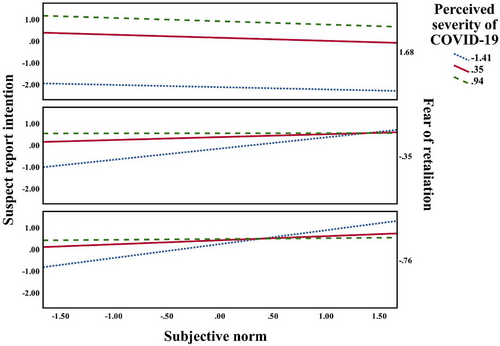

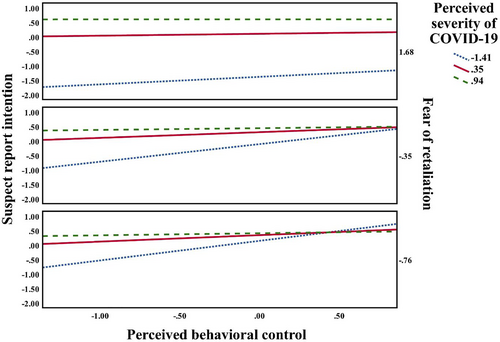

Table 5 shows the results of the third moderated moderation model. This model shows the three-way interactions among PBC, PSC, and FR on SRI. PBC was positively associated with SRI supporting hypothesis H3. The interaction of PBC and PSC and the interaction of PBC and FR negatively predicted SRI. Hence, H4c was not supported and H5c was supported. The unconditional interaction among PBC, PSC, and FR was significant (b = 0.10, p = 0.001). Hence, H6b was supported.

| Paths | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC→SRI | 0.25 | 0.03 | 8.01 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.31 | H3 supported |

| PBC × PSC→SRI | −0.21 | 0.03 | −10.36 | 0.001 | −0.25 | −0.17 | H4c not supported |

| PBC × FR→SRI | −0.09 | 0.04 | −2.20 | 0.029 | −0.16 | −0.01 | H5c supported |

| PBC × PSC × FR→SRI | 0.06 | 0.02 | 2.67 | 0.008 | 0.02 | 0.11 | H6c supported |

The conditional effects of PBC and PSC interaction on SRI at different values of FR are showed in Figure 4. PSC moderates the relationship between PBC and SRI only when the FR is low (−0.76), medium (−0.35) as well as highest (1.68). But the effect size decreases with an increase in extent of FR.

4 DISCUSSION

Research on public's SRI during any infectious disease outbreak is rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explain general public's SRI during COVID-19. This study extended TPB by including PSC and FR in the model to understand SRI better. PSC and FR were positively correlated with SRI. The results indicated that people's attitude, subjective norm, and PBC were positively associated with SRI. PSC and FR negatively moderated the relationships of attitude, subjective norm, and PBC with SRI. Moderation of PSC also varied at different values of FR. The findings that attitude, subjective norm, and PBC positively associates with SRI confirms the findings of the studies on unethical behavior reporting intention (Carpenter & Reimers, 2005), crime report intention (Harvey, 2009; Keller & Miller, 2015), and whistleblowing intention (H. Park & Blenkinsopp, 2009) literature. In addition, this study establishes that an extended TPB provides better explanation of SRI of the public during an infectious disease outbreak.

In line with the extant literature on TPB, attitude, subjective norm, and PBC were found to be associated with intention formation (Andarge et al., 2020; Frounfelker et al., 2021; Keller & Miller, 2015). People's favorable attitude, supportive subjective norm, and strong PBC toward SRI were positively associated with high SRI. PBC was the most potent predictor of SRI followed by subjective norm and attitude. So, it can be said that, if people believe that they can report and have the opportunity or easy access (helpline or online reporting portal) to report, they will report. People whose family members, friends, and others had a positive attitude toward SRI were more likely to show SRI during the COVID-19 outbreak. Finally, people with positive attitude toward SRI believed that by reporting about a person suspected with COVID-19 can help in curbing the spread of the disease, hence showed more SRI.

This study highlights the importance of the interaction of PSC with attitude, subjective norm, and PBC predicting SRI. It was found that when people perceived the severity of COVID-19 to be very high, their attitude was negatively associated with their SRI. Such findings contradict some studies (Faasse & Newby, 2020; Zickfeld et al., 2020) and concurs with some other studies which report that PSC decreases or was not a predictor of health-protective behavior (Jadil & Ouzir, 2021; Wise et al., 2020) among people during COVID-19. The possible explanation for such findings can be many. First, appraisal of the negative consequences of SRI might have been greater than that of the negative consequences of COVID-19 (Witte, 1992). Second, people's unrealistic optimism about contracting the disease (Dolinski et al., 2020; Park et al., 2021; Wise et al., 2020) might have acted against their SRI. Third, conspiracy theories (e.g., COVID-19 is a hoax, threat of COVID-19 is exaggerated; Douglas, 2021; Uscinski et al., 2020) might have tempted people to underestimate or ignore the severity of COVID-19 and thereby negatively affecting their SRI (Allington et al., 2020).

PSC also negatively moderated subjective norm-SRI relationships. Such findings differ from the findings of the recent studies (e.g., Andarge et al., 2020; Aschwanden et al., 2021; Shubayr et al., 2020) which established positive association between subjective norm and health-protective behaviors during COVID-19. TPB literature confirms that the association between subjective norm and intention is the weakest (Ajzen, 1991; Armitage & Conner, 2001) because people are more likely to act in accordance with their personal beliefs rather than conforming to the beliefs of others (Stiff & Mongeau, 2016). As people themselves, their significant others might not have been free from optimism biases or immune to COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Therefore, people might have perceived no pressure from their significant others to report suspected cases of COVID-19.

PSC also negatively moderated PBC-SRI relationships contradicting the findings of recent studies (e.g., Andarge et al., 2020; Aschwanden et al., 2021; Shubayr et al., 2020). Even when perceiving COVID-19 as severe, people's PBC was negatively associated with SRI. In the initial phases of COVID-19, SRI might have been deterred by lack of awareness among people about the availability of multiple convenient means to report about the presence of people suspected with COVID-19 in their locality. And those who were aware of the means of suspect reporting lacked trust in the health administration that any action will be taken, or anonymity will be maintained (Bish & Michie, 2010). Lack of trust in authorities and dissatisfaction with the communications received about suspect reporting might have helped people to have less control over their SRI.

This study also highlights the negative association of FR with SRI. If people perceive high FR, then they are least likely to engage in SRI. Apart from the direct association, this study also emphasized the interaction of FR with attitude, subjective norm, and PBC predicting SRI for the first time. It was revealed that when people's attitude, subjective norm, and PBC were negatively associated with their SRI when they had extremely high FR from the suspected people or family members of suspected people. This finding confirms studies which establish that people do not report unethical behavior when they perceive reprisal from the supervisor or from the organization (Mayer et al., 2013) and do not report crime when they perceive retaliation from the police (Papp et al., 2019). In India, people live in a collectivist society and do not like social isolation or loss of social relationships, so they may not intend to go against the interest of a person of their community or even other community in their vicinity suspected with COVID-19. There were instances of verbal and physical violence including killing of the suspect reporter by the COVID-19 suspect in India (Tewary, 2020; The New Indian Express, 2020a). This might be able to explain why FR negatively moderated attitude-SRI, subjective norm-SRI, and PBC-SRI relationships.

This study found that FR moderated the interactions between each component of TBP and PSC (attitude × PSC, subjective norm × PSC, and PBC × PSC) to predict SRI. In the moderated moderation models, three 3-way interactions significantly predicted SRI. PSC moderated the attitude-SRI, subjective norm-SRI, and PBC-SRI relationships at different levels of FR. The moderated moderation effect is highest when FR is low, and it decreases with an increase in extent of FR. The interaction of attitude and PSC predicts SRI more when FR is less and moderate. When people have less and moderate FR, then their favorable attitude toward SRI and high PSC will result in their SRI. When FR is high, favorable attitude combined with high PSC will not result in SRI, because people are overwhelmed with the fear of social rejection, psychological threat, and physical violence. The interaction of subjective norm and PSC predicts SRI more when FR is less and moderate. When people have less and moderate FR, then their supportive subjective norm and high PSC will result in SRI. But when they perceive extremely high FR, even if their family members, friends, and peers approve their SRI and they have high PSC, they will not engage in SRI. The effect of the interaction of PBC and PSC on SRI is more when FR is less and decreases with the increase in FR. People will less likely engage in SRI, if they have high FR, even if they believe they are capable of reporting and perceive COVID-19 as very severe. If people have high FR, their SRI will be low irrespective of how positive their attitude is, how strong their subjective norm and PBC are, and how severe they perceive COVID-19.

5 IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study have implications for academicians, health administrators, as well as policymakers. This research provides a starting point for further research on SRI as a health-protective behavior. Findings of this study adds to the literature on reporting intention and health-protective behavior by explaining SRI using an extended model of TPB. Such findings can help health administrators to develop interventions to make the public feel they have control over their own behavior and to facilitate their ability to report. Health administrators may provide multiple methods of suspect reporting convenient to all sections of people with provisions of anonymity. Health administrators may develop and maintain online portals and mobile applications apart from strengthening the existing telephone-based complaint registration system for collecting information about people with suspected with COVID-19. Health administrators may also generate awareness among public using all forms of media about the available options and procedure to report about people suspected with COVID-19 and other COVID-19 protocol violators. Understanding the predictors and inhibitors of SRI can also help policymakers to make policies to facilitate suspect reporting such as policies to provide sufficient protection to and forbid retaliation against the reporters.

6 LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Notwithstanding the contributions, this study has few limitations. First, the convenience sample limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the sample represented the collectivist society of India, hence findings cannot be generalized to public in other individualistic countries. Finally, the intent to report a person suspected with COVID-19 symptoms was studied, not actual reporting behavior. Actual reporting is also very difficult to capture and verify public's claim. The moderating effect in this study is low indicating possible presence of other moderators. Hence, future research can test this model using other moderators like conspiracy theory beliefs, locus of control, and self-efficacy in both individualistic and collectivistic countries. COVID-19 is a complex social event and numerous other sociocultural issues may affect SRI such as religious belief, population density etc. which needs to be studied in the context of SRI.

7 CONCLUSION

This study contributes to our understanding of SRI as a new health-protective behavior during COVID-19 pandemic. During any pandemic, people can aid in curbing the spread of the disease by reporting people considered to be potential spreaders. The findings of this study provide evidence that attitude, subjective norm, and PBC predict SRI. In addition, the findings also offer evidence how PSC and FR decrease the effect of attitude, subjective norm, and PBC on SRI. PBC emerged as the most potent predictor and FR was the most potent inhibitor of SRI. High FR was found to debilitate the combined or individual association of PSC, attitude, subjective norm, and PBC with SRI. If people want, they can report about the suspected cases only if they do not have any FR. Hence, the Government must take necessary steps to ensure complete anonymity of the reporter during infectious disease spread.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

APPENDIX

| Construct | Questions |

|---|---|

| Attitude | 1. Reporting about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood isa Good: –1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Bad |

2. Reporting about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood is Harmful: –1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Beneficial |

|

3. Reporting about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood isa Ethical: –1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Unethical |

|

| Subjective norm | 1. Most people who are important to me think that I should report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhooda True:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: False |

2. Most people whose opinions I value would approve of me reporting about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood Improbable:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Probable |

|

3. My parents/family members will Discourage me to report: –1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Encourage me to report |

|

| Perceived behavioral control | 1. I am confident that I can report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhooda True:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: False |

2. Whether I report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood is completely up to me Disagree:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Agree |

|

3. If I really wanted to, I could report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhooda Likely:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Unlikely |

|

| Reporting intention | 1. I intend to report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood.a Definitely do:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Definitely do not |

2. I am willing to report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood. False:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: True |

|

3. I plan to report about a COVID-19 suspect in my neighborhood.a Agree:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Disagree |

|

| Perceived severity of COVID-19 | Not severe at all: –1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Very much severe |

| 1. The infection rate of COVID-19 can be | |

| 2. The death rate of COVID-19 can be | |

| 3. The negative impact of COVID-19 on social order can be | |

| Fear of retaliation | Strongly disagree:–1—2—3—4—5—6—7–: Strongly agree |

| 1. My personal relationship with the person suspected with COVID-19 after reporting him/her will become worse. | |

| 2. I have observed others in my neighborhood facing retaliation after reporting about a person suspected with COVID-19. | |

| 3. I will report about a person suspected with COVID-19, because I fear no retaliation.a |

- a Reverse coded items.

Biographies

Sitanshu Sekhar Das is an Assistant Professor in the OB & HR area at the Rajagiri Business School, Kochi, India. His research interests include subjective well-being, mental health, and organizational behavior. His research featured in Current Psychology, Journal of Constructivist Psychology, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, Psychological Studies, Death Studies, Journal of Loss & Trauma. He is also an Editorial Board Member of Data in Brief.

Vipul Kumar is working as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the Kashi Naresh Government Post Graduate College, Gyanpur, Bhadohi, UP, India. He is also a visiting faculty to the Department of Psychology, University of Allahabad, India. His area of expertise are health psychology and organizational psychology.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data will be made available upon request.