Natural resources and economic growth: Does political regime matter for Tunisia?

Abstract

The discussion on the effect of natural resources on economic growth remains a contentious issue of scientific research. An emerging issue to this discussion is the role of political regime in determining the nature of the growth and natural resource nexus. Consequently, this study examines the effect of natural resources on the economic growth of Tunisia and how the country's political regime moderates this relationship using annual time series data over the 1970–2017 period. Regression analysis established that in the long-run natural resources generally have positive effects on the country's economic growth, while political regime has mixed effects on economic growth. The interaction between political regime and resources indicates democracy enhances the positive gains from natural resources on economic growth although in the short run, the outcome is mixed. The effects of specific natural resource (oil, mineral, and forest rents) on sectoral growth are positive. Political regime interacts with oil, mineral, and forest rents to propel growth in the agricultural sector. The study concludes that democratic regime is crucial for the effective utilization of resources for long-run economic growth in the country. Beyond natural resource abundance examined in this study, there is a further need to analyze the extent to which the economy relies on these natural resources and its effect on the economy in future studies. This would elucidate the “natural resource blessings” estimated in this study. The role of other measures of institutional quality on the subject matter can be explored in Tunisia and other countries in future studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

The importance of economic growth to the socio-economic development of all economies cannot be overemphasized. Hence, policymakers, researchers, and governments have sought to identify growth-enhancing factors for their countries. Increasing number of empirical studies have analyzed and reported a number of factors that influence economic growth. These factors include capital, labor, government expenditure, trade openness, and foreign aid (Ho & Iyke, 2020). Others are energy consumption, research and development (Adedoyin et al., 2020; Kose et al., 2020), political and administrative systems, administrative systems and Socio-cultural factors (Boldeanu & Constantinescu, 2015) among others.

One factor whose possible effect on economic growth has received counter-argument is natural resources. For many decades, researchers have not reached a consensus on the impact of natural resources on economic growth. Some argue that natural resources positively affect economic growth because they can induce more investment in economic infrastructure and more rapid human capital development (Sachs & Warner, 1999; Zeynalov 2017; Sinha & Sengupta, 2019) and also facilitate a country's industrial development by providing investable funds and domestic markets (Benramdane, 2017; Krueger, 1980). These arguments, however, have been questioned by many authors following Sachs and Warner's (1995) empirical revelation that resource-scarce economies tend to exhibit higher economic growth than resource-rich economies. They, therefore, opine that natural resources may be a curse to growth because they can shrink the manufacturing sector (Zeynalov 2017), lead to rampant rent-seeking conflicts and political instability (Zeynalov 2017), and “crowding-out” of investment in human capital (Raggl, 2017).

The importance of nature for human existence or the survival of mankind has been duly noted by (Nathaniel & Bekun, 2020). However, over the past years, empirical studies that tested whether natural resources are a blessing or a curse to growth have found mixed results (Ding and Field 2005; Benramdane, 2017; Alexeev and Conrad 2009; Brunnschweiler and Bulte 2008; Oyinlola et al., 2015; Erdoğan et al. (2020); Bildirici and Gokmenoglu (2020). Other researchers (Auty & Gelb, 2001; Campos & Nugent, 1999; Murshed, 2004) have also noted that a country's quality of institution including political regime will determine whether natural resources would be a blessing or a curse to its economic growth. Researchers have therefore shown keen interest to investigate the effect of political regime and other institutional qualities on natural resource–growth nexus (Amini 2018; Amiri et al., 2019; Bah, 2016; Moshiri & Hayati, 2017; Doces, 2020). The current study is therefore set out to investigate the effect of natural resources on economic growth in Tunisia and how political regime affects the relationship between natural resources and growth.

Tunisia is naturally endowed (Good, 2015; Gylfason & Zoega, 2006; Oyinlola et al., 2015; Raggl, 2017) with phosphates, petroleum, zinc, lead, and iron ore. It is the world's fifth and Africa's second-leading producer of phosphate (AZO mining, 2012). According to the United States Energy Information Administration, Tunisia has shale formations with an estimated 23 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas and 1.5 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Its daily oil and natural gas production are about 60,000 barrels and 6 billion cubic feet, respectively (Good, 2015), and until recently, it was a net energy exporter. Over the years, the contribution of natural resources to the country's GDP remains significant. The World Development Indicators (WDI, 2019) illustrates that the share of total natural resource rent to the country's economic growth ranged between 12.011% in 1975 and 16.73% in 1980 after which it fell gradually to 1.6% in 1998. From 1998, the share saw an upward trend until 2008 when it reached 9.6%. It however took a nosedive to reach 2.8% in 2015. Further analysis shows that between 2005 and 2014, the share of oil rent to GDP was between 3.3% and 5.9%. The share of mineral rents has increased from 0.04% to 0.4% within the same period, and that of forest rent has been between 0.09% and 0.37% within the same period (WDI, 2019).

For decades, Tunisia has been considered as one of the economic success stories on the African continent especially when it recovered from the 2009 economic crisis to witness a GDP growth of 3.5% in 2010 (World Bank 2019). However, economic growth performance has been weak following political crises in 2011. The economy grew by 1.8% in 2017 compared to 1.2% in 2016 and 1.1% in 2015. Also, the country's economic growth has averaged 2.3% post revolution compared to 4.5% in the 5 years before the revolution. The economic growth of Tunisia has generally fluctuated over the years recording negative growth rates of −0.65% in 1973, −0.49% in 1982; −1.44% in 1986, and −1.91% in 2011. It also ranged between 3.41% and 7.87% from 1975 to 1980; between 0.07% and 7.81% from 1988 to1998; and between 1.32% and 6.70% from 2000 to 2010 (World Bank, 2019).

With these patterns of economic performance, it is unclear the effect of natural resources on the country's economic growth. Similarly, recent literature has concluded that the economic growth effect of natural resource wealth is dependent on quality institutions such as political regime (Amini 2018; Bah, 2016; Moshiri & Hayati, 2017). Therefore, in examining the impact of natural resources on Tunisia's economic growth, the study incorporates the role of political regime in the natural resource and economic growth relationship. Asiedu (2016) has documented that strong democratic institutions serve as an impetus for economic growth by providing channels of attracting foreign direct investments, foreign aid, and also promote entrepreneurship. Also, strong democracy is associated with less corruption and efficient usage of economic resources, thereby promoting growth. On the other hand, weak democratic institutions would negatively affect economic performance. Although there have been few cases of political revolution in Tunisia, it has, according to the World Bank (2018), become quintessential in the Middle East and North Africa region by progressing toward the completion of political transition to an open and democratic system of governance. Since 1987, the country has enjoyed some level of political stability through its multiparty democracy which was characterized by some level of autocracy. However, in 2011, the serene political climate was disturbed by antigovernment protests leading to the election of a new president to restore political stability. Thus, the quality of the political regime in Tunisia may interplay with the natural resource to affect the level of growth.

Even though economic growth studies on Tunisia exist (Hassen & Anis, 2012; Dhaoui 2013; Elmakki et al., 2017), there is a paucity of research on the natural resource–economic growth nexus. In cases where a closer study exists, it is mainly an expressive analysis (Good, 2015), devoid of quantitative analysis or the country is part of a pooled sample (Gylfason and Zoega 2006) without a detailed analysis of Tunisia both of which are not appropriate for long-term considerations. The mixed empirical evidence in the literature on whether abundant resources are good or bad for economic growth requires that focus is placed on understanding the circumstances or conditions under which these are true. Despite this, the role of the political regime in Tunisia's natural resource–growth nexus remains unknown. This study, therefore, fills this gap and makes contributions to the literature in three-folds. First, it provides evidence from an African country to augment the few empirical studies on natural resource–growth nexus, given that many African countries are endowed with natural wealth but have a high level of poverty. Second, some natural resource–growth and development nexus authors (Woolcock et al., 2001) have argued that “it may not be natural resource endowment per se but its type that matters” (Murshed, 2004). Therefore, the paper examines the effect of the overall natural resource as well as specific analysis for oil, mining, and forest resources. Third, apart from an analysis of the overall economic growth, the effect of natural resources and political regime on sectoral growth of Tunisia is estimated.

The remaining sections of the paper proceed as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature related to the study; Section 3 presents theoretical and empirical modeling with other methodological components; Section 4 discusses the results of the study; and Section 5 presents a conclusion of the study with policy implications/recommendations.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Economic growth, through the lenses of neoclassical growth theory, is explained by capital, labor, natural resources, and exogenous technological progress. Capital propels economic growth since a higher capital investment increases productivity (Barro, 2003). Labor is argued to positively affect growth by enhancing innovation and the adoption of new technologies (Ho & Iyke, 2020). The exogenous technological progress is argued to be influenced by other factors including political institutions (Asiedu, 2016; Gómez-Puig & Sosvilla-Rivero, 2018). Natural resources are an important source of wealth around the world. However, their contribution to growth and development is debatable. Thus, natural resources are argued to support economic growth and development by providing a major source of revenue for governments of resource-rich countries. Such revenues support governments' effort to provide the necessary infrastructure. Natural resources also provide jobs and source of income to many people, thereby helping to reduce poverty levels in many low- and middle-income countries (OECD, 2011). Natural resources have been a strong foundation for the industrialization process by providing raw materials for manufacturing firms. The abundance of natural resources has also facilitated international trade among countries (Willebald et al., 2015).

On the flipside, others (Gylfason & Zoega, 2006; OECD, 2011) have documented many reasons why natural resources can become a curse. The first is that over-dependence on natural resources, which are generally a fixed factor, may witness diminishing returns in its contribution to growth. Also, rent-seeking and corrupt behavior associated with natural resource impede growth and development via the diversion of resources. These proponents argue that the abundance of natural resources can lead to Dutch disease where increased exports of natural resources increase the real exchange rate of the currency and reduce manufacturing and services exports.

Moreover, investment in natural resource extraction to yield immediate benefits leads to underinvestment of human capital which has long-term consequences (Zeynalov 2017; Sinha & Sengupta, 2019). It is therefore not surprising that countries without the advantages of endowment in natural resources have experienced higher growth through the development of “productive capacity and attracting productive investment by building physical infrastructure and developing human capital, especially in vocational education and transforming the university system” (Oqubay, 2020). However, many countries and regions have seen a rise in their consumption of natural resources in their bid to experience higher economic growth and development. For instance, the Asia and Pacific region have documented that its economic transformation hinges on natural resource usage such that between 2000 and 2017, the use of natural resources more than doubled, while it increased by only 29% in the rest of the world. Although it is expected that the consumption of natural resources in the region shall continue to rise toward higher economic growth, the environmental degradation effect of heavy reliance on natural resources has led to calls for sustainable management of natural resources and green growth agenda (The Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP], 2020).

The above conflicting arguments and developments have propelled many to wade institutional quality into the discussion (Auty & Gelb, 2001; Paltseva & Roine, 2011). Institutional quality like political regime, rule of law, and corruption can determine whether natural resources would propel economic growth and development or otherwise. Accordingly, Kaznacheev (2017) contended that resource economies with better political institutions manage their revenues better and achieve economic growth and social development than countries with poor political institutions. Mehlum et al. (2006) have also concluded that grabber-friendly institutions can be bad for growth in resource-rich economies, while producer-friendly institutions do the opposite. Furthermore, resource-rich economies characterized by a low-quality institution may impede efficient resource allocation that may negatively affect economic growth (Rodrik, 2004). In the growth literature, the effect of political regime has gained attention. It is argued that democracy promotes economic growth since governments often put up growth-enhancing infrastructure (Doces, 2020), supports foreign direct investments and entrepreneurial development (Asiedu, 2016), and enhances political rights, civil rights, human rights, and rule of law for its citizens (Veisi, 2017).On the other hand, authoritarian rule reduces growth since it is associated with wastage of resources and corruption in other to get the political loyalty of the population (Zaloznaya, 2015). However, some researchers have noted that “countries with dictatorships have been predicted to grow as rapidly as democracies, perhaps even faster” (Okunlola, 2019; 184). In this accord, it can be posited that the effect of a particular political regime on economic growth may differ from country to country.

Empirical evidence on the subject matter abound however, they offer mixed results. For instance, Gylfason and Zoega (2006) have revealed that although the Central African Republic, Mali, Niger, Sierra Leone, Zambia, and Botswana are endowed with natural resources in large quantities, the effects on the growth for these economies differ. Evidently, revenue gained from Botswana's natural resources contributes positively toward the country's economic growth and development, while the other countries witnessed negative per capita growth. The work of Lane and Tornell (1996) on the relationship between institutions and resource curse revealed that extreme rent-seeking behavior among resource-rich economies impede growth. Leite and Weidmann (2002) investigation on the impact of natural resource abundance on the economic growth of some resource-rich nations revealed that natural-resource abundance has no direct impact on economic growth. However, there was an indirect negative effect through corruption. Benramdane (2017) examined the oil price volatility and economic growth in Algeria using data for 1970–2012 period. It was found that oil price volatility negatively affects the Algerian economy, while oil price boom increases growth. However, the negative growth effects of oil price volatility offset the positive impact of the oil boom. Having estimated an insignificant effect of crude oil production on the economic growth of Cameroon, Tamba (2017) explained that this effect can be due to the nontransparent of oil revenues; high levels of corruption in the sector and tax evasion; and oil price volatility.

Boschini et al. (2007) examined the growth impacts of four natural resource indicators for 80 nations from 1975 to 1998 and found that natural resources reduce economic growth, while the interaction between natural resources and institutions increases growth. Contrary to Boschini et al. (2007), Owusu (2015) noted that natural resources and institutions improve economic growth, while their interaction decreases the growth of 58 developed and developing countries. On their part, Adu (2012) and Bah (2016) found no support for the resource curse hypothesis in Ghana and Sierra Leone, respectively. Bah (2016) further showed that quality institutions improve economic growth of Sierra Leone. However, Olayungbo and Adediran (2017) found for the Nigerian economy that in the long run, oil revenue and institution reduce growth, while the opposite holds in the short run. Mehlum et al. (2006) found among a sample of 87 countries that resource abundance reduces economic growth, institution increases growth, while their interaction promotes growth. Raggl's (2017) analysis of 113 countries saw oil rent to be a significant contributor to economic growth, while aggregate natural resource rent recorded an insignificant effect, although positive. Again, it was found that rule of law increases economic growth, while interactive effect with oil rent was insignificant.

Amini (2018) investigated 22 advanced countries and 61 underdeveloped and developing countries within the period between 1996 and 2010. The research findings included insignificant effect of natural resource abundance, institutions, and their interactions. Alpha and Ding (2016) investigated the impact of natural resources endowment on economic growth in Mali from 1990–2013, and their results proved that natural resources export has a positive impact on economic growth. However, an interaction between natural resources export and corruption leads to a decline in economic growth. Moshiri and Hayati (2017) studied 149 countries during 1996–2010 years and showed that while fuel dependency has no significant effect on GDP growth, agriculture and food dependency increases GDP growth in the presence of high institutional qualities. Moshiri and Hayati (2017) also explained that government's effectiveness, regulatory quality, and rule of law are more effective in avoiding the negative effect of resource dependency. Oyinlola et al., (2015) analysis of African countries indicated a positive relationship between natural resource abundance and economic growth and a positive effect of political stability, rule of law, and voice and accountability on economic growth. Also, the interaction between natural resources and institutions confirmed it is not the mere abundance of resources that determine growth but rather economic growth is occasioned by good governance in the abundance of natural resources. A recent empirical study by Aljarallah and Angus (2020) revealed that the overreliance on natural resources in Kuwait has been detrimental to its economy over the long run, while Erdoğan et al. (2020) also recorded an insignificant effect of oil export on 11-oil producing countries. Conversely, a study by Bildirici and Gokmenoglu (2020) on precious metal abundance and economic growth for top precious metal producer countries for the period of 1963–2017 revealed that precious metal abundance has a positive effect on economic growth both in the long and short run. Similarly, Balsalobre-Lorente et al. (2019) analyzed the relationship between natural gas consumption and economic growth in Iran. Regression analysis by the authors confirmed a positive effect of natural gas consumption on economic growth. Zhang and Brouwer (2020) examined the relationship between natural resource abundance and economic growth in China. With empirical evidence collected from 44 studies published between 2005 and 2017 in the Chinese city level, it was found that the presence of the resource curse remains equivocal. They, however, concluded that evidence for or against the resource curse hypothesis is dependent on the prevalence of specific conditions. Although the effect of political regime on economic growth has been examined empirically for different countries and regions with varied outcomes (Doces, 2020; Okunlola, 2019), there is little evidence on how regime type interacts with natural resources to influence economic growth. It is in this regard that the study analyses the effect of the interaction between natural resource and political regime on economic growth.

3 METHODS AND MATERIALS

3.1 Theoretical and empirical model

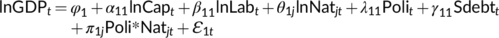

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

(3) (4a)

(4a) (4b)

(4b) (4c)

(4c) (4d)

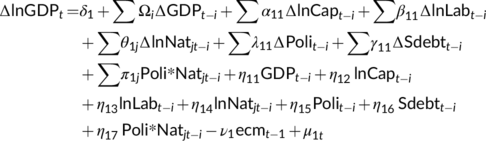

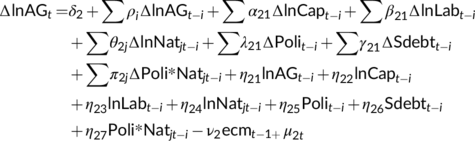

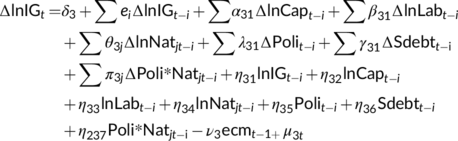

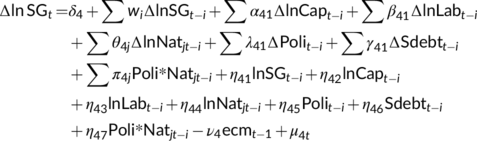

(4d)Empirically, four (4) models were estimated for each equations (i.e., (4a), (4b), (4c), and (4d)) by using different specific and composite natural resources indicator and interaction term.

3.2 Econometric method

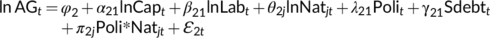

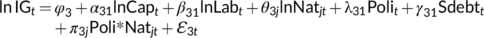

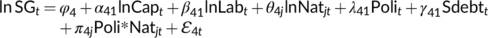

(5a)

(5a) (5b)

(5b) (5c)

(5c) (5d)

(5d)3.3 Data source and description

Except Polity 2 that is sourced from Polity IV Project (http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm) the rest of the data is from the World Development Indicator [2020] database. Time series data used for this study cover the period of 1970- 2017. The study could not use data beyond 2017 because some of the variables have no data after this period. As explained in the previous section, the study used the following explanatory variables for estimation. Capital was measured as gross fixed capital formation at constant 2010US$ and total population as a measure of labor. Debt service was measured by debt service on external debt (Sdebt), and political regime was measured by polity2 (a political regime for autocracy and democracy). It ranges between −10 for autocracy and 10 for democracy. The other explanatory variables include total rent from natural resources (Nat) as % of GDP, rent from mining (Min) as % of GDP, rent from oil (Oil) as % of GDP, and rent from forestry (For) as % of GDP. The dependent variables are economic growth (GDP) proxied by GDP as constant 2010US$, agricultural sector growth (AG) denoted by agriculture value added at constant 2010US$, industrial sector growth (IG) measured by industry value added as constant 2010US$, and service growth (SG) proxied by service industry value added as constant 2010US$.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Descriptive statistics of variables and correlation analysis

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables considered in this study. On average, the gross fixed capital formation of the country over the period is about 5.4 billion with a maximum of over 11 billion dollars. The high capital formation of the country reflects the commitment of policymakers in Tunisia to invest in areas that will enhance further productions. The average total population for the economy over the period is over 8.4 million people; starting from a little over 5 million in 1970 to over 11.4 million people in 2017. The results also show that average debt service on the external debt of the country is over US$ 1 billion. This is considerably high and could help normalize the country's indebtedness in the global market. Polity2 in the country ranged from −9 to about 4.9, with a mean of about −4. This implies that the country can be classified as an anocracy (a combination of autocracy and democracy). Over the 47 years, the average GDP of the country is about 24.9 billion dollars, with a maximum of over 49 billion dollars. The sectoral growth shows that on average, the industrial sector had the highest mean growth of over 7.5 billion dollars, while agriculture and service sectors had a mean of over 2.3 and 1.4 billion dollars, respectively. Among the natural resources, the share of oil in total resource rent records a mean value of 5.44%, while forest rent has a mean of 0.20% and mineral rent with a mean of 0.50%. This together with their respective minimum and maximum values reported is an indication that among the three natural resources, oil's contribution to the total rent is greatest for the Tunisia economy over the period. Overall, the natural resource rent of the country is averaged 6.3% of total resource rent.

| Variables | Unit of measurement | Mean | Medium | Maximum | Minimum | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cap | US$ | 5.45 billion | 4.55 billion | 11.40 billion | 1.35 billion | 2.97 billion |

| Lab | People | 8.48 million | 8.88 million | 11.43 million | 5.06 million | 1.98 million |

| Sdebt | US$ | 1.31 billion | 1.4 billion | 3.03 billion | 0.072 billion | 0.84 billion |

| GDP | US$ | 24.9 billion | 21.3 billion | 49.7 billion | 6.35 billion | 13.6 billion |

| IG | US$ | 7.51 billion | 7.33 billion | 12.8 billion | 1.84 billion | 3.49 billion |

| AG | US$ | 2.37 billion | 2.36 billion | 4.39 billion | 0.79 billion | 1.00 billion |

| SG | US$ | 14.8 billion | 6.79 billion | 57.10 billion | 0.37 billion | 16.4 billion |

| Poli | scale of −10 to 10 | −4.083 | −4.000 | 7.000 | −9.000 | 4.850 |

| Nat | % of GDP | 6.322 | 5.042 | 17.057 | 1.674 | 4.133 |

| Oil | % of GDP | 5.438 | 4.273 | 16.608 | 1.316 | 3.864 |

| Min | % of GDP | 0.504 | 0.108 | 3.766 | 0.006 | 0.949 |

| For | % of GDP | 0.201 | 0.1844 | 0.414 | 0.089 | 0.079 |

The results of correlation analysis to ascertain the direction of movement (association) among the variables is reported in Table 2. The results reveal that capital, labor, debt, polity2, and mineral rent have positive correlation with GDP as well as growth in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors, while total natural resource, oil, and forest rents have negative correlation with GDP and growth in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors. Among the explanatory variables for the specific regression analysis, the results show a mixed of positive and negative association not very close to one to entertain fears of multicollinearity.

| GDP | Cap | Lab | Nat | Sdebt | Poli | AG | IG | SG | Oil | Min | For | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | 1 | |||||||||||

| Cap | 0.977 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Lab | 0.953 | 0.898 | 1 | |||||||||

| Nat | −0.385 | −0.259 | −0.481 | 1 | ||||||||

| Sdebt | 0.936 | 0.885 | 0.960 | −0.425 | 1 | |||||||

| Poli | 0.870 | 0.858 | 0.840 | −0.454 | 0.801 | 1 | ||||||

| AG | 0.981 | 0.945 | 0.953 | −0.429 | 0.933 | 0.871 | 1 | |||||

| IG | 0.975 | 0.936 | 0.983 | −0.406 | 0.957 | 0.804 | 0.962 | 1 | ||||

| SG | 0.964 | 0.963 | 0.858 | −0.352 | 0.849 | 0.903 | 0.935 | 0.883 | 1 | |||

| Oil | −0.451 | −0.335 | −0.511 | 0.971 | −0.453 | −0.494 | −0.490 | −0.454 | −0.432 | 1 | ||

| Min | 0.002 | 0.062 | −0.137 | 0.402 | −0.136 | −0.121 | −0.017 | −0.055 | 0.055 | 0.175 | 1 | |

| For | −0.017 | 0.064 | −0.111 | 0.115 | −0.131 | 0.271 | −0.060 | −0.150 | 0.152 | 0.114 | −0.044 | 1 |

4.2 Unit root and cointegration results

The results of the unit root test are presented in Table 3. The results show that at levels, the presence of unit root among the variables is rejected for all variables except GDP and agricultural sector growth. The implication is that most of the variables are nonstationary at levels. Therefore, the first differences of the variables were tested, and the results show that all variables become stationary at their first difference.

| Variable | Levels, t-Statistic | Breakpoint period | First difference, t-Statistic | Breakpoint period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnCap | −3.346 | 1992 | −5.145*** | 1988 |

| lnLab | −2.542 | 2002 | −4.841*** | 1996 |

| lnSdebt | −4.083 | 1981 | −7.682*** | 1981 |

| Poli | −1.535 | 1999 | −6.562*** | 1994 |

| lnGDP | −3.866*** | 1999 | −8.425*** | 1997 |

| lnIG | −3.331 | 2011 | −8.627*** | 1989 |

| lnAG | −7.041*** | 1990 | −6.825*** | 1990 |

| lnSG | −1.203 | 2011 | −8.003*** | 1997 |

| InNat | −3.195 | 2005 | −6.850*** | 1986 |

| lnOil | −2.980 | 1986 | −7.521*** | 1999 |

| lnMin | −4.582 | 2008 | −7.226*** | 1978 |

| lnFor | −2.979 | 2010 | −10.385*** | 2008 |

- *** Denotes 1% level of significance.

The cointegration results of the variables are reported in Table 4. For simplicity, the study reported on the one that uses total natural resources rent in the estimation (similar results were obtained for the other resource rent model. They are available upon request). The results show that there is cointegration among the factors irrespective of the choice of a dependent variable (general economic growth or sectoral growth). This is because the F-statistics of all models are significantly different from the upper and lower bounds at all alpha (significant) levels. This suggests the presence of long-run equilibrium relationships among the variables.

| Total growth modelF-stat | Industry modelF-stat | Service modelF-stat | Agric. modelF-stat | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.830*** | 9.242*** | 5.586*** | 9.520*** | |||||

| α levels | I(0) bound | I(1) bound | I(0) bound | I(1) bound | I(0) bound | I(1) bound | I(0) bound | I(1) bound |

| 10% | 2.12 | 3.23 | 2.12 | 3.23 | 2.12 | 3.23 | 2.12 | 3.23 |

| 5% | 2.45 | 3.61 | 2.45 | 3.61 | 2.45 | 3.61 | 2.45 | 3.61 |

| 1% | 3.15 | 4.43 | 3.15 | 4.43 | 3.15 | 4.43 | 3.15 | 4.43 |

- *** Denotes 1% level of significance.

4.3 Discussion of long-run regression results

4.3.1 General/aggregated economic growth, natural resources, and political regime nexus

The results of the estimated long-run effects have been reported in Table 5. The results show that total natural resource rent, oil, mineral, and forest rents significantly exert positive effects on general economic growth. This, therefore, refutes the school of thought that natural resources are a curse to the economic development and hence accept that natural resources are blessings to the country. It also supports previous works including Balsalobre-Lorente et al. (2019), Ding and Field (2005), and Alexeev and Conrad (2009). The effect of political regime on general economic growth is mixed recording negative effects on the total natural resource rent and oil models (models 1–2), insignificant effect in the mineral model (model 3) and positive effect in the forest model (model 4). The negative significant effect of political regime does not overly ride-off the importance of democratic institutions in economic growth as seen in Table 4 (models 1–2). However, it highlights that the democratic structure of the country may be associated with a poorly implemented governance system, high corruption, and its subsidiaries, thereby limiting the efficient utilization of resources for economic development. The results of Rachdi and Saidi (2015) also established that democracy has a negative effect on economic growth of Middle East and North Africa countries including Tunisia, and they attributed this to the abuse of democratic processes. Thus, similar argument can be given for the negative effect of political regime reported in models 1–2 of Table 4. The positive effect of political regime on economic growth in model 4 is in line with arguments by Doces (2020), Asiedu (2016), and Veisi (2017) that strong democratic regime suppports economic growth by enhancing infrastructure; supporting foreign direct investments as well as entrepreneurial development; and the promotion of civil rights, human rights, and rule of law for its citizens, respectively.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnCap | 0.385*** | 0.308** | 0.383*** | 0.337*** |

| (0.0.087) | (0.115) | (0.126) | (0.069) | |

| lnLab | 2.061*** | 2.5074*** | 2.812*** | 1.271** |

| (0.442) | (0.689) | (0.473) | (0.619) | |

| lnSdebt | −0.103* | −0.142 | −0.294** | −0.050 |

| (0.052) | (0.086) | (0.109) | (0.087) | |

| Poli | −0.026*** | −0.015* | 0.003 | 0.057*** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.018) | |

| InNat | 0.146*** | |||

| (0.032) | ||||

| lnOil | 0.149*** | |||

| (0.043) | ||||

| lnMin | 0.037* | |||

| (0.021) | ||||

| lnFor | 0.190** | |||

| (0.098) | ||||

| Poli*lnNat | 0.017*** | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| Poli*lnOil | 0.011 | |||

| (0.008) | ||||

| Poli*InMin | 0.014** | |||

| (0.006) | ||||

| Poli*InFor | 0.054*** | |||

| (0.014) | ||||

| Constant | −15.700*** | −20.192*** | −23.401*** | −4.078 |

| (4.499) | (7.129) | (5.079) | (7.790) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

Notwithstanding the above conflicting effects recorded for political regime, it is seen that the interaction between natural resources and political regime gives positive significant effects on economic growth. Thus, in examining whether political regime could influence the natural resource–growth nexus, following Ehigiamusoe (2020) and Wooldridge (2016), the partial effect of natural resource is taken where it is observed that there is an interaction effect between natural resources and political regime. This means the positive economic gains from natural resources are complemented by the political regime of the country. Thus, the democratic governance in Tunisia has reinforced the positive effects of natural resources on economic growth supporting the evidence and assertion by Oyinlola et al. (2015) that in the abundance of natural resources, good governance is necessary to promote economic growth.

Other factors that significantly influence economic growth are capital, labor, and debt servicing. While capital and labor have positive significant effects on economic growth, debt servicing has negative effect on economic growth. In both the classical Cobb–Douglas model and the Harrod–Domar model, capital is an essential factor for economic growth. Therefore, this finding justifies the need for improving capital formation in the Tunisian economy. Consistently, Bal et al. (2016) estimated a positive effect of capital formation on the economic growth of India. Brini et al. (2016) also revealed that increased investment in Tunisia's economy would lead to its expansion. Similar to capital formation, labor increases the economic growth of Tunisia. In a developing country like Tunisia where technological advancement is low, human labor is crucial for undertaking economic activities. Therefore, increasing labor availability in the country is essential to improve its economic growth. However, this should be associated with improved labor skills to ensure that labor is fit-for-purpose and efficient. Servicing of external debt has negative effects on economic growth in all models, but this is statistically significant in only models 1 and 3. This implies that servicing of debts tends to reduce economic growth over the long term. This is because debt servicing crowds current investment, thereby slowing economic growth over the period. This raises an important question on the long-term effect of loans (debt) on the economic fortunes of a developing economy. Mohamed (2013) examined the impact of public external debt on economic growth of Tunisia and found that external debt beyond 30% of the country's GDP would lead to a decline in economic growth of the country. The result of Mohamed (2013) also showed that Tunisia is already in the negative portion of the Laffer-curve where a decline in economic growth is associated with increased debt. Similarly, Brini et al. (2016) argued from Tunisia's perspective that there is long-run causality between debt servicing and economic growth.

4.3.2 Sectoral growth, natural resources, and political regime nexus

Table 6 focuses on the relationship between natural resources, political regime, and growth of the agricultural sector of Tunisia. The results established that total natural resource rent, oil, mineral, and forest rents significantly exert positive effects on agricultural sector growth. This is an indication that natural resources have helped the development of Tunisia's agricultural sector. The effect of political regime is once again mixed as it increases agricultural sector growth under mineral and forest models (models 3–4) but reduces growth in the sector under the total resource rent model (model 1). However, the interaction of natural resources (both aggregate and specifics) and political regime gives significant positive coefficients effects. The implication is that the positive gains in the agricultural sector from natural resources are complemented by becoming more democratic just as it was seen under the general growth model. This suggests that there is efficient utilization of natural resources under democratic governance for agriculture development. Also, while capital and labor contribute positively to the growth of the agricultural sector, debt servicing exerts the opposite effect. The earlier explanations given under the general growth model to justify the effect of labor, capital, and debt servicing are applicable here.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnCap | 0.213*** | 0.267*** | 0.144 | 0.115* |

| (0.067) | (0.148) | (0.120) | (0.061) | |

| lnLab | 1.591*** | 0.617 | 1.469* | 2.168*** |

| (0.429) | (0.963) | (0.645) | (0.347) | |

| lnSdebt | −0.091* | −0.027 | −0.097 | −0.136*** |

| (0.049) | (0.109) | (0.105) | (0.046) | |

| Poli | −0.021** | 0.002 | 0.022** | 0.051*** |

| (0.008) | (0.017) | (0.010) | (0.015) | |

| InNat | 0.140*** | |||

| (0.028) | ||||

| lnOil | 0.301** | |||

| (0.114) | ||||

| lnMin | 0.049* | |||

| (0.022) | ||||

| lnFor | 0.128* | |||

| (0.075) | ||||

| Poli*lnNat | 0.023*** | |||

| (0.007) | ||||

| Poli*lnOil | 0.044** | |||

| (0.015) | ||||

| Poli*InMin | 0.010** | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| Poli*InFor | 0.041*** | |||

| (0.012) | ||||

| Constant | −6.890 | 6.228 | −2.972 (8.340) | −12.748*** |

| (4.607) | (10.633) | (4.108) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

Regarding the service sector, the results reported in Table 7 reveal that there is no significant effect from oil, mineral, and forest resources but total natural resource rent positively affects the growth of the service sector. The possible intuition behind this outcome is that the service sector largely relies on human resources other than these individual natural resources. However, the returns from the composite natural resources can become useful for growth of the sector through the investment of returns in human capital, technological, and other activities in the service sector. Also, political regime records a negative significant effect on the growth of the service sector if composite natural resources is assumed (model 1) but insignificant effect if the resources are independently analyzed (models 2–4). The interactions of composite natural resources with political regime show a positive significant effect on the service sector's growth. This means that becoming more democratic reinforces the positive effect on natural resources on the service sector. Like other results (Tables 5 and 6), capital and labor have a significant positive effects on the service sector, while debt servicing has a negative but insignificant effect on the sector.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnCap | 1.560*** | 0.778*** | 0.619*** | 0.683*** |

| (0.187) | (0.167) | (0.060) | (0.099) | |

| lnLab | 1.633 | 4.658*** | 4.750*** | 4.890*** |

| (0.970) | (0.871) | (0.550) | (0.644) | |

| lnSdebt | 0.014 | −0.142 | −0.081 | −0.144 |

| (0.093) | (0.110) | (0.078) | (0.095) | |

| Poli | −0.080*** | −0.012 | −0.008 | −0.025 |

| (0.020) | (0.014) | (0.007) | (0.018) | |

| InNat | 0.218** | |||

| (0.099) | ||||

| lnOil | −0.017 | |||

| (0.056) | ||||

| lnMin | 0.0148 | |||

| (0.021) | ||||

| lnFor | 0.083 | |||

| (0.092) | ||||

| Poli*lnNat | 0.077*** | |||

| (0.020) | ||||

| Poli*lnOil | 0.003 | |||

| (0.007) | ||||

| Poli*InMin | −0.001 | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| Poli*InFor | −0.008 | |||

| (0.013) | ||||

| Constant | −38.207*** | −65.444*** | −64.759*** | −66.144*** |

| (10.385) | (9.858) | (6.711) | (7.505) |

- ***and **denotes 1% and 5% level of significance respectivel. SE in parenthesis.

Finally, Table 8 shows that total natural resource rent, capital, labor, and debt servicing have positive effects on industrial sector growth. The positive effect of debt servicing on industrial growth although not expected can be attributed to the possibility that the international community may have high confidence in the country as a result of its high debt servicing rate and invest in industrial activities of the country. The finding can also be surmised to reflect the argument by Muhanji et al. (2019) that when external debt bridges the saving-investment gap in a manner that productively expands a country's production base, indebtedness would promote growth. The significance of only aggregate natural resources and not the specific natural resources on the growth of the industrial sector implies that natural resources only have a significant effect on the industrial sector if there is a diversified natural resource but not when there is an exploitation of a specific natural resource in the economy. Therefore, if natural resources must improve the industrial sector, the Tunisian government has to ensure that there is no emphasis on the utilization of any specific natural resources, instead, each must be explored simultaneously. Surprisingly, the interaction of political regime with natural resources has an insignificant effect on the growth of the industrial sector. This could be that the political regime has not supported the use of natural resources to propel the development of the industrial sector.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnCap | 0.267*** | 0.322*** | 0.388*** | 0.274*** |

| (0.036) | (0.060) | (0.034) | (0.021) | |

| lnLab | 0.465*** | 0.324 | 0.767*** | 0.080 |

| (0.239) | (0.277) | (0.265) | (0.296) | |

| lnSdebt | 0.214*** | 0.218*** | 0.138*** | 0.273*** |

| (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.040) | (0.044) | |

| Poli | −0.006 | −0.011* | −0.011*** | 0.028** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.012) | |

| InNat | 0.035* | |||

| (0.019) | ||||

| lnOil | 0.023 | |||

| (0.021) | ||||

| lnMin | −0.007 | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| lnFor | 0.030 | |||

| (0.045) | ||||

| Poli*lnNat | −0.002 | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| Poli *lnOil | 0.003 | |||

| (0.004) | ||||

| Poli *InMin | −0.008 | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| Poli *InFor | 0.024 | |||

| (0.008) | ||||

| Constant | 4.982 | 5.942* | −1.074 | 9.871** |

| (2.957) | (3.119) | (3.601) | (3.622) |

- *** and **denotes 1% and 5% level of significance respectively. SE in parenthesis.

4.4 Discussion of short-run regression results

The short-run results are reported in Tables 9–12. Table 9 reveals total natural resource rent and oil rent positively affect economic growth. However, political regime reduces the positive effect that total natural resources have on economic growth. Also, a mixed effect of labor is reported in the short run. Regarding the agricultural sector, its short-run growth is positively affected by forest resource rent and the interaction between political regime and forest rent and mineral rent (Table 10). In the short-run, mineral and forest resources rent supports the development of the industrial sector, while oil rent reduces the sector's growth. Again, political regime reinforces the positive effect of total natural resource rent and the negative effect of oil rent on industrial growth (Table 11). The results reported in Table 12 indicate while total natural resource rent increases growth in the service sector, the individual resource rents have insignificant effect on service growth in the short run. In this sector, political regime reinforces the positive gain from total natural resource rent on the development of the service sector. However, the negative and significant coefficients of all the ECMt−1 support the fact that there is a long-run relationship among the variables in the various models.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DlnCap | 0.131*** | 0.114** | 0.215*** | 0.195*** |

| (0.044) | (0.044) | (0.059) | (0.047) | |

| DlnLab | 0.704*** | 0.640*** | −13.334* | −5.276*** |

| (0.190) | (0.206) | (7.076) | (1.784) | |

| DlnSdebt | 0.021 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.037** |

| (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.023) |

(0.018) | |

| DPoli | −0.008** | −0.003** | −0.001 | 0.016** |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.006) | |

| DInNat | 0.049*** | |||

| (0.012) | ||||

| DlnOil | 0.038*** | |||

| (0.010) | ||||

| DlnMin | 0.008 | |||

| (0.006) | ||||

| DlnFor | 0.034 | |||

| (0.026) | ||||

| DPoli*lnNat | −0.003*** | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| DPoli *lnOil | −0.004 | |||

| (0.014) | ||||

| DPoli *InMin | 0.004 | |||

| (0.010) | ||||

| DPoli *InFor | 0.010*** | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| ECMt−1 | −0.341*** | −0.255*** | −0.450*** | −0.214** |

| (0.064) | (0.054) | (0.138) | (0.078) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DlnCap | 0.497** | 0.506** | 0.774*** | 0.655*** |

| (0.206) | (0.204) | (0.212) | (0.131) | |

| DlnLab | 1.545*** | 1.523** | 1.894*** | 1.209** |

| (0.547) | (0.598) | (0.446) | (0.515) | |

| DlnSdebt | 0.033 | 0.026 | −0.034 | 0.111 |

| (0.095) | (0.098) | (0.087) | (0.079) | |

| DPoli | 0.015 | 0.027 | 0.031*** | 0.055** |

| (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.011) | (0.021) | |

| DInNat | 0.010 | |||

| (0.054) | ||||

| DlnOil | −0.006 | |||

| (0.052) | ||||

| DlnMin | 0.020 | |||

| (0.017) | ||||

| DlnFor | 0.135* | |||

| (0.078) | ||||

| DPoli*lnNat | 0.003 | |||

| (0.006) | ||||

| DPoli*lnOil | 0.001 | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| DPoli*InMin | 0.005* | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| DPoli*InFor | 0.023*** | |||

| (0.011) | ||||

| ECMt−1 | −0.747*** | −0.750*** | −0.768*** | −0.575*** |

| (0.144) | (0.145) | (0.140) | (0.147) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DlnCap | 0.497*** | 0.254*** | 0.464*** | 0.268*** |

| (0.050) | (0.053) | (0.074) | (0.064) | |

| DlnLab | 1.545 | 18.204*** | 16.288 | 24.267** |

| (7.924) | (6.163) | (23.970) | (8.896) | |

| DlnSdebt | −0.170*** | 0.059** | 0.074** | −0.071** |

| (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.035) | (0.033) | |

| DPoli | −0.055*** | 0.002 | −0.005 | −0.009 |

| (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| DInNat | 0.015 | |||

| (0.022) | ||||

| DlnOil | −0.036*** | |||

| (0.012) | ||||

| DlnMin | 0.019* | |||

| (0.009) | ||||

| DlnFor | 0.039*** | |||

| (0.016) | ||||

| DPoli*lnNat | 0.881*** | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| DPoli*lnOil | −0.006*** | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| DPoli*InMin | 0.001 | |||

| (0.001) | ||||

| DPoli*InFor | 0.005 | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| ECMt−1 | −0.747*** | −0.826*** | −1.319*** | −1.026*** |

| (0.149) | (0.153) | (0.214) | (0.187) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DlnCap | 0.585*** | 0.271** | 0.239** | 0.241** |

| (0.124) | (0.103) | (0.098) | (0.087) | |

| DlnLab | 0.104 | 22.193 | 18.576 | 20.815 |

| (0.144) | (15.615) | (12.489) | (14.215) | |

| DlnSdebt | 0.006 | −0.052 | −0.045 | −0.060 |

| (0.042) | (0.043) | (0.035) | (0.041) | |

| DPoli | −0.045** | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.001 |

| (0.016) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| DInNat | 0.100* | |||

| (0.050) | ||||

| DlnOil | −0.006 | |||

| (0.020) | ||||

| DlnMin | 0.001 | |||

| (0.010) | ||||

| DlnFor | 0.035 | |||

| (0.039) | ||||

| DPoli*lnNat | 0.022** | |||

| (0.008) | ||||

| DPoli*lnOil | 0.001 | |||

| (0.002) | ||||

| DPoli*InMin | −0.004 | |||

| (0.017) | ||||

| DPoli*InFor | −0.003 (0.005) |

|||

| ECMt−1 | −0.458*** | −0.366*** | −0.574*** | −0.419*** |

| (0.090) | (0.096) | (0122) | (0.091) |

- *** , **, and * Denote 1%, 5%, and 10% level of significance, respectively. SE in parenthesis.

In all, the mixed effect of the interaction between political regime and natural resources on economic growth in the short run implies moving toward democratic governance may sometimes be associated with an inefficiency in the management and utilization of revenue from some natural resources in the short run. However, based on the fact that in the long run, the interaction effect between political regime and natural resources leads to a positive outcome, it can be concluded that political regime positively affects the long-term growth benefit the country derives from its natural resources. A similar conclusion can be made of the effect of the natural resources on growth in both runs.

4.5 Model diagnostic test

The diagnostic test results for the ARDL estimation technique are shown in Table 13. For want of space, the diagnostic test results for the model that uses the total natural resource rent have been reported. Similarresults were obtained for the other resource rent models. The result shows that the F-value for serial correlation fails to reject the assumption that there is no serial correlation in the model. The Jarque–Bera test for normality is based on the null hypothesis that the skewness and excess kurtosis of the variables are zero. The results show that there is evidence to conclude the error terms are normally distributed. The insignificant of the autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity test implies that the errors are homoscedastic. Finally, the stability of the model using the Ramsey Regression Equation Specification Error Test shows that the estimated models are all stable. Thus, the estimated models are robust and reliable since they do not suffer from the problem of autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity, nonnormality, and nonstability.

| Diagnostic | Test | Total growth | Industrial growth | Service growth | Agricultural growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial correlation | Breusch–Godfrey, F-stat | 1.242 (0.304) | 1.423 (0.259) | 1.985 (0.985) | 1.974 (0.153) |

| Normality | Jarque–Bera | 0.376 (0.828) | 1.260 (0.532) | 7.033 (0.031) | 0.26 (0.871) |

| Heteroscedasticity | ARCH, F-stat | 0.253 (0.617) | 1.035 (0.314) | 2.093 (0.105) | 0.893 (0.592) |

| Stability | Ramsey RESET, F-stat | 0.306 (0.761) | 1.465 (0.154) | 1.582 (0.127) | 0.766 (0.390) |

- Note: Probability in parenthesis.

- Abbreviations: ARCH, autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity; RESET, Ramsey Regression Equation Specification Error Test.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

- The direct effect of political regime on aggregate and sectoral growth is mixed both in the short- and long-run periods

- The indirect effect of political regime on aggregate and sectoral growth via its interaction with natural resources in the short run is mixed. In the long run, however, political regime interacts with natural resources to ensure positive economic growth.

- Total natural resource rent enhances sectoral and aggregate growth, while the agricultural sector benefits significantly from the oil, mineral, and forest rents in the long run.

- Capital support growth in both the short and long run. Labor also supports long-run growth, but the effect on growth is mixed in the short run, while the effect of debt serving has a long-run negative effect on growth generally.

The above findings have generated some policy implications. Firstly, there is a rejection of a resource curse hypothesis in the Tunisian economy in the long run. This is evident by the positive effect of total and specific natural resources mainly oil and mineral resources on economic growth. This is an indication that it is possible for a country to manage its natural resources well to propel economic growth. In the case of Tunisia, it implies the extraction of the country's natural resources has the potential to in the long run translate into economic growth.

Secondly, the direct effect of political regime on economic growth is mixed. Thus, both positive and negative effects of becoming more democratic political regimes on economic growth were recorded. The nature of the effect was dependent on a particular resource rent used in the model. One can conclude that under certain conditions, democratic political regime can be vital for directly ensuring growth in specific sectors and overall growth in the economy of Tunisia.

Thirdly, when it comes to the utilization of natural resources to support growth, the interaction between political regime and resources denoted that democracy in the country has been helpful in the effective management of the natural resources of the country to support economic growth in the long run than the short run. Thus, as the country moves toward democratic regimes, the positive role of natural resources in the growth of the country is reinforced. This informs that the growth rate of the economy does not necessarily depend on the abundance of the resources but rather on the efficient utilization of the resources. Therefore, it is concluded from this that indirectly, democratic regimes are crucial for the effective utilization of resources for economic growth. Accordingly, it is imperative for political authorities in the country to strengthen their checks and balances regarding the utilization of natural resources in order to consolidate the economic gains from natural resources.

Finally, in the long run, labor and capital remain significant factors explaining the general economic and sectoral growth of Tunisia. Therefore, these factors must be carefully considered especially under natural resource management and exploitation. For instance, human capital development may be required to improve the positive roles of labor on economic growth of the country. Beyond natural resource abundance examined in this study, there is further need to analyze the extent to which the economy relies on these natural resources and its effect on the economy in future studies. This would elucidate the “natural resource blessings” estimated in this study. The role of other measures of institutional quality on the subject matter can be explored in Tunisia and other countries in future studies.

Biographies

Paul Adjei Kwakwa, PhD is a Senior Lecturer with the School of Management Sciences and Law, University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana where he teaches economics and economics-related subjects. His research interests focus on economic growth, economic development, and environmental and resource economics. His recent articles have been published in the Journal of Energy and Development, OPEC Energy Review, The International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review and Journal of environmental Management among others.

Dr. William Adzawla holds a PhD in Economics from University of Cheikh Anta Diop, Senegal and a Master of Philosophy (MPhil) degree in Agricultural Economics from University for Development Studies, Ghana. He doubles as an Agricultural and Climate Change Economist. Dr. Adzawla has in-depth knowledge in policy analysis and socioeconomic research and experienced in data management and analysis. Currently, he is the Economist at IFDC Ghana. He has published several journal articles especially in the areas of climate change and adaptation, gender, poverty, livelihoods and crop production. His research goal is to identify how inequality in all forms can be addressed and ensure all-inclusive global development.

Hamdiyah Alhassan (Ph.D.) is a development economist and a senior lecturer at the Department of Applied Economics, University for Development Studies, Ghana. She has published dozens of peer-reviewed academic papers with her research interest including environmental and resource economics, and financial and monetary economics. Dr. Hamdiyah Alhassan has over 9 years of training, research and professional experience in financial and monetary economics, and environmental and resource economics.

Abigail Achaamah holds an MSc. in Financial Risk Management from the Presbyterian University College, Ghana. Her research interest lies in the area of financial and monetary economics, and economic growth and development.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators