Three New Perspectives on the Perfect Storm: What's Behind the Obesity Epidemic?

Disclosure: The authors declared no conflict of interest.

The rising rates of obesity were first observed in the United States in the late 1980s (1), and the problem is now observed in more than 30 countries, making this a global epidemic (2). Despite the best intentions to reduce this burden, no country has been successful in reversing the increasing rates of obesity prevalence (2). In the United States, an estimated 70.7% of adults age ≥ 20 years have overweight or obesity (3). Perhaps more alarming are the increasing prevalence rates in US children (4) and in children around the globe (5). According to statistical forecasts, by 2030, 51% of the US population will have obesity (6). Because obesity is a major driver of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers, it has been estimated that even a one percentage point reduction from the predicted trend to 2030 would reduce obesity-attributable medical expenditures by $84.9 (± $9.3) billion over two decades (6).

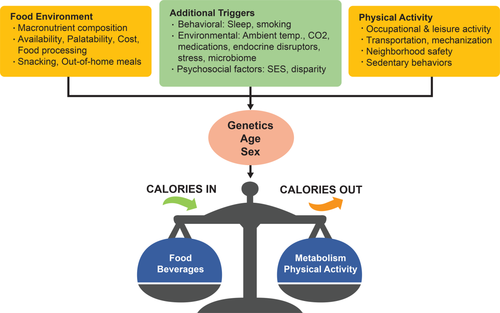

Overweight and obesity occur when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure over an extended period. As most of the increase in obesity has occurred in the past 40 years, it is inappropriate to place the blame for the epidemic on genetics alone. As Joslin described almost a century ago, genetics probably loads the gun, while lifestyle in our obesogenic environment pulls the trigger for the spreading of the obesity epidemic. As shown in Figure 1, the secular rises in overweight and obesity prevalence have to be explained by the action on genetically susceptible individuals of a combination of physiological and behavioral factors that are triggered by the changes in the food environment and the environmentally driven reductions in physical activity. However, additional environmental, behavioral, and socioeconomic cues and triggers have been proposed to influence energy intake and/or expenditure, causing weight gain in genetically susceptible individuals (7).

As illustrated by the energy balance equation (energy stores = calories in − calories out), overweight and obesity occur when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure over an extended period. The secular rises in overweight and obesity prevalence have to be explained by a combination of physiological and behavioral factors triggered by the changes in the food environment and the environmentally driven reductions in physical activity. Depending on the genetic susceptibility, age, and sex of individuals, such changes result in variable weight gain. However, the often cited major contributors, i.e., the food environment and physical activity environment (orange), are not the only factors implicated in the obesity epidemic. Other environmental obesity promoters (green), such as increased atmospheric CO2 levels, living in thermoneutrality most of the year, spending countless hours in front of electronic screens, being exposed to chemicals known to disrupt endocrine functions, increased consumption of medications, and the composition of one's microbiome, may all tip the energy balance equation in an unhealthy direction.

In this issue of Obesity, we asked three groups of investigators to provide us with their personal view (Perspectives) on the respective roles of the food environment (8), the decrease in physical activity (9), and other environmental and/or behavioral factors (10) in triggering the obesity epidemic.

First, Hall (8) reviews the potential roles of recent changes in dietary macronutrient content (protein, fat, and carbohydrate) on weight gain. He concludes that the overall caloric content, rather than changes in a single macronutrient, is to blame for the overall population weight gain. More specifically, he hypothesizes that the changes in the quantity and quality of the food supply in conjunction with a drastic increase in the consumption of highly processed, palatable, and cheap food (with high amounts of sugar, fat, salt, and flavor additives) have triggered overconsumption of calories. The traditional normative eating behaviors have progressively switched from time-consuming home meal cooking to more ubiquitous snacking and eating of large-portion-size meals, often at restaurants.

In the second Perspective (9), Church and Martin remind us that formal exercise (regular recreational exercise) has not changed over the past few decades but occupational activity has. Indeed, by 2006, only 20% of American jobs required high levels of physical activity, thus representing a huge drop from the 1960s when more than 50% of jobs required levels of physical activity that met the current daily physical activity goals. Interestingly, Church and Martin propose that the present low level of occupational activity has pushed most people into a zone of low energy expenditure in which intake becomes somewhat uncoupled to expenditure.

Finally, in the third Perspective (10), Davis, Plaisance, and Allison update the list of other environmental and behavioral factors that may have ramped up the prevalence of obesity beyond the role of the “big two,” i.e., food environment and physical activity. They propose that poor sleep hygiene and decreased cigarette smoking can both push the energy balance toward a surplus of energy. Similarly, environmental factors, such as increased atmospheric levels of CO2, living in thermoneutrality most of the year, spending countless hours in front of electronic screens, being exposed to chemicals known to disrupt endocrine functions, and increased consumption of medications, can all tip the energy balance equation in an unhealthy direction. Finally, they add to the list the potential role of an unhealthy microbiome and the undisputed role of socio-physiological factors such as economic disparity to the long list of weight gain drivers.

In summary, the three Perspectives come at the right time to remind us that human-engineered changes in environmental conditions have resulted in improved health (reduction in infectious disease and extension of life-span) but have also triggered an epidemic of noncommunicable chronic diseases, such as obesity and its comorbidities. These environmental changes have set up the perfect storm to create what has been called the "obesogenic environment.” In turn, this has caused a new epidemic of chronic disease, which will eventually reverse most of the benefits of what research and novel medications have done to eradicate most of the infectious diseases. The challenge of upcoming decades will be to reverse some of these deleterious trends toward poor health.

Can we learn from other epidemics? Too much malaria? Drain the swamps and eradicate the mosquitoes. Too many deaths on highways? Impose speed regulations and the use of seat belts. Too many health problems related to obesity? Reverse some of the environmental changes that have triggered the rise in the prevalence of obesity. Where to start? Redesign our built environment to be more conducive to walking, biking, and grocery shopping. Encourage physical activity from the youngest age in the school system and within families. Incentivize the food industry in being part of the solution by producing and marketing novel healthy food. Develop public health policies mandating changes in the food and environmental sectors to create better health. Create a safe environment with minimal amounts of pollutants. All these proactive steps could help in reversing the tide and solving this societal health problem. The other alternative is to develop safe and effective medical approaches to weight management, an expensive solution for a worldwide epidemic. However, doing nothing about the epidemic is not an option because we cannot afford to wait for the long process of genetic selection to progressively favor a less “thrifty genotype” resisting abundance, i.e., a “spendthrift genotype.”