Perceptions of Barriers to Effective Obesity Care: Results from the National ACTION Study

Funding agencies: Novo Nordisk, Inc.

Disclosures: LMK reports nonfinancial support from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Ethicon, Fractyl, Gelesis, GI Dynamics, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Rhythm, and Zafgen outside the submitted work. AG reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Health Scripts (Orexigen) and Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. KJ is on the advisory group for the obesity study referenced in the paper. She also works for the Integrated Benefits Institute (IBI), a nonprofit membership association; funder of this research, Novo Nordisk, is on IBI's Board. RLK reports other support from Duke University and personal fees from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. TKK reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Eisai and NutriSystem outside the submitted work. ML reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Novo Nordisk outside the submitted work. PMO reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study; and grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, grants from Weight Watchers International, and personal fees from Janssen, Pfizer, and Medscape/WebMD outside the submitted work. KJT reports other support from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study. NVD reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and American Egg Board; and grants from Vital Health Interventions outside the submitted work; in addition, Dr. Dhurandhar has several US and international patents issued.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03223493.

Abstract

Objective

ACTION (Awareness, Care, and Treatment in Obesity maNagement) examined obesity-related perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors among people with obesity (PwO), health care providers (HCPs), and employer representatives (ERs).

Methods

A total of 3,008 adult PwO (BMI ≥ 30 by self-reported height and weight), 606 HCPs, and 153 ERs completed surveys in a cross-sectional design.

Results

Despite several weight loss (WL) attempts, only 23% of PwO reported 10% WL during the previous 3 years. Many PwO (65%) recognized obesity as a disease, but only 54% worried their weight may affect future health. Most PwO (82%) felt “completely” responsible for WL; 72% of HCPs felt responsible for contributing to WL efforts; few ERs (18%) felt even partially responsible. Only 50% of PwO saw themselves as “obese,” and 55% reported receiving a formal diagnosis of obesity. Despite HCPs' reported comfort with weight-related conversations, time constraints deprioritized these efforts. Only 24% of PwO had a scheduled follow-up to initial weight-related conversations. Few PwO (17%) perceived employer-sponsored wellness offerings as helpful in supporting WL.

Conclusions

Although generally perceived as a disease, obesity is not commonly treated as such. Divergence in perceptions and attitudes potentially hinders better management. This study highlights inconsistent understanding of the impact of obesity and need for both self-directed and medical management.

Introduction

Despite increasing consensus that obesity is a serious, complex, and chronic disease with considerable negative impact on individual health and quality of life, as well as a significant societal burden (1-8), addressing and treating obesity within the standard medical context are uncommon. Increased awareness of a pathophysiological basis for obesity has led to its growing recognition as a disease by the health care community, but strong stigma persists against individuals with obesity and health care providers who treat them (9, 10). Only a small minority of patients with obesity receive clinically proven lifestyle, pharmacological, and/or surgical interventions (11). Although attitudes toward obesity are changing (12-14), there appear to be strong impediments to effective care including obesity prevention policies, behavior change communication, and health care professional training (15-17). Broad-based efforts across multiple stakeholder groups are needed to identify the most critical barriers to effective obesity management. To advance these efforts, the ACTION (Awareness, Care, and Treatment in Obesity maNagement) study aimed to identify perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and potential barriers to effective obesity care across three respondent types: people with obesity (PwO), health care providers (HCPs), and employer representatives (ERs). Specific aims were to gain greater understanding of barriers preventing PwO from receiving effective obesity care and support and to generate insights and recommended strategies to guide collaborative action promoting effective care for PwO.

Methods

Procedure

This study, sponsored by Novo Nordisk Inc., was approved by the Copernicus Group Independent Review Board (18). Separate surveys to assess obesity-related perceptions, behaviors, and barriers were developed for PwO, HCPs, and ERs based on literature review and qualitative research (19). Surveys were developed collaboratively with the ACTION study steering committee, a multidisciplinary team of professionals (including study authors) specializing in obesity management within clinical practice, scientific investigation, patient advocacy, employer human relations, and public policy. Surveys were designed to facilitate comparisons within and across respondent types (see online Supporting Information for surveys).

Surveys were pretested among 10 PwO, 10 HCPs, and 3 ERs using 45-minute Web-assisted telephone interviews to assess clarity, face validity, and relevance. Data were collected via online surveys using a cross-sectional design. Additionally, PwO completed two previously psychometrically validated measures, Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) (20, 21), measuring general health-related quality of life and weight-related quality of life, respectively. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03223493).

Data collection and participants

Data were collected from October 29 to November 12, 2015. All respondents were recruited via email or telephone through an online panel company to which respondents had provided permission to be contacted for research purposes.

To reduce possible sampling bias and enhance generalizability, stratified sampling techniques were used based on self-reported demographic criteria. PwO criteria included age, household income, race/ethnicity, gender, and geographic region. HCP criteria included practice setting, years in practice, geographic region, and professional training. The HCP stratified sampling plan included recruiting primary care providers (PCPs) and obesity specialists at a 5:1 ratio. PCPs were those practicing in primary care (i.e., general practice, family practice, and internal medicine). Obesity specialists were those practicing in primary care, endocrinology, bariatrics, or bariatric surgery and identified as an obesity/weight loss (WL) specialist and/or those who saw at least 50% of their patients for obesity. ERs were selected from companies with 500 or more employees, divided equally into those with 500 to 999, 1,000 to 4,999, and 5,000 or more employees.

Prior to completing surveys, respondents provided informed consent. PwO inclusion criteria were age ≥18, US residency, and BMI ≥30 kg/m2 based on self-reported height and weight. HCP inclusion criteria included employment in US facilities (except Vermont to comply with Sunshine reporting requirements), spending a minimum of 70% of professional time in patient care, seeing ≥100 patients during the previous month with ≥10 patients in need of weight management, practicing 2 to 35 years in their current role, and board certification or eligibility in their chosen specialty (for physicians). Inclusion criteria for ER respondents included age ≥18, working in the United States for companies with ≥500 employees offering health insurance, responsible for making or influencing decisions about employee health insurance or health and wellness programs, and reported believing there is a “weight issue” among their employee population. ERs and HCPs were excluded if they reported working in market research, marketing, public relations, or pharmaceutical/medical device manufacturing.

Five-point end-anchored Likert scales assessed agreement, in which 1 meant “do not agree at all” and 5 meant “completely agree.” Responses of 4 or 5 were coded as “agree” and are reported as such unless otherwise noted. The SF-12 and IWQOL-Lite were scored according to standard scoring algorithms (20, 22). Table 1 provides scores on both instruments.

| PwO | HCPs | Employers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 3,008), N (%) | (n = 606), N (%) | (n = 153), N (%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1,378 (46) | 305 (50) | 73 (48) |

| Female | 1,630 (54) | 301 (50) | 80 (52) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 54.5 (14.3) | –a | 49.6 (9.1) |

| BMI classification | |||

| Underweight | 16 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| Normal range | 298 (49) | 62 (41) | |

| Overweight | 201 (33) | 61 (40) | |

| All obesity classes | |||

| Class I | 1,304 (43) | 59 (10) | 25 (16) |

| Class II | 896 (30) | 16 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Class III | 808 (27) | 16 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Provider specialty | |||

| Family practice | 298 (49) | ||

| General practice | 49 (8) | ||

| Internal medicine | 241 (40) | ||

| Bariatric surgery | 1 (0) | ||

| Endocrinology | 8 (1) | ||

| Bariatrics/obesity medicine | 9 (2) | ||

| Employer size | |||

| High-end medium: 500-999 employees | 51 (33) | ||

| Large: 1,000-4,999 employees | 49 (32) | ||

| Jumbo: 5,000 or more employees | 53 (35) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37 (6) | 25 (5) | 26 (5) |

| Quality of life (weighted) | |||

| SF-12, physical component summary | 47 (10) | ||

| SF-12, mental component summary | 47 (11) | ||

| IWQOL-Lite, total score | 68 (21) |

- Percentages may add to more than 100% due to rounding.

- SF-12 measures a patient's quality of life, covering 12 domains with 12 questions, generating physical and mental component summary scores, with higher scores indicating better quality of life; general population norm = 50. IWQOL-Lite is scored in total and on five distinct functional categories, with values ranging from 0 (the most severe impairment) to 100 (no quality of life impairment).

- a Category ranges only asked.

- PwO, people with obesity; HCPs, health care providers; SF-12, Short Form Health Survey; IWQOL-Lite, Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite.

To reduce potential selection bias, respondent-level, individual weighting was applied to the PwO sample. Using an established weighting methodology (23), final data were weighted to representative demographic targets for age, household income, ethnicity, race, Hispanic descent, gender, and US region based on the 2010 US Census (24). Participant characteristics are reported for the final unweighted sample. All other results are weighted unless otherwise specified.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis (means, frequencies) was performed using SPSS 15.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). Tests of differences (χ2, t tests) within respondent types were performed using SPSS tables; additional analysis was performed using Stata/IC 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 using two-tailed tests. Multiple test corrections were not applied to statistical tests, as this research was exploratory and descriptive in nature.

Results

Response rates for PwO, HCP, and ER surveys were 9.7%, 20.4%, and 14.6%, respectively. Completion times averaged 51.4 minutes, 58.9 minutes, and 37.1 minutes, respectively. Suspension rates (i.e., not completing the survey) were 13.3%, 12.7%, and 4.3%, respectively, typically occurring during the informed consent process (see Supporting Information Figures S1-S3 and Table S1 for sample dispositions).

Characteristics for the final sample for all groups are displayed in Table 1 (additional details in Supporting Information Table S2). Adult PwO (n = 3,008, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), 606 HCPs (83% PCPs, 17% WL specialists), and 153 ERs completed the surveys.

PwO survey results

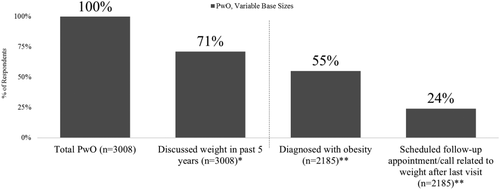

Figure 1 illustrates types of obesity-related interactions PwO may have experienced with HCPs. Seventy-one percent of PwO spoke with an HCP about their weight within the past 5 years; fifty-five percent reported being diagnosed with obesity (additionally, 77% reported overweight diagnoses, with some reporting both). Thirty-eight percent of PwO discussed a WL plan with an HCP within the past 6 months. For many, these discussions came after numerous reported “serious WL efforts” in their adult lifetime (median = 3, mean = 7; Supporting Information Figure S4).

PwO and HCP interactions. PwO, variable base sizes. *Either “discussed being overweight” (68%) or “discussed losing weight” (64%) with their HCP. **Among those 71% who have had a conversation in the past 5 years. Dashed line indicates base size changes. PwO, people with obesity; HCP, health care provider.

While all PwO had self-reported heights and weights equating to obesity criteria (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), only 50% perceived themselves as “obese” or “extremely obese.” The remaining reported having “overweight” (48%) or “normal weight” (2%). More than two-thirds of PwO considered obesity to be as or more serious than many other health conditions, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression (Supporting Information Figure S5).

Among PwO, 18% reported that “committed to a WL plan” best describes them today. Among those who had spoken with an HCP within the past 6 months, 26% reported having “committed to a WL plan.” Of those PwO who had WL discussions in the past 5 years, 47% reported typically bringing up weight with their HCP at appointments, and 53% reported their HCP bringing it up.

Among PwOs who had spoken with their HCP in the past 6 months, the most frequently reported goals included “to lose (any amount) of weight,” “to improve my existing health conditions,” “to reduce the risks associated with weight/prevent a health condition,” or “to not gain any more weight” (Supporting Information Table S3). PwO who discussed WL and were recommended specific WL goals by their HCP reported the average goal was 20% WL, consistent with the WL PwO reported needing to be satisfed with their efforts (20%). When recommendations were made for a specific reduction in pounds, the mean recommended WL was 47 pounds.

In ascertaining WL among PwO, 23% reported a current weight at least 10% less than their maximum weight during the previous 3 years. Of these, 44% (10% of the total PwO sample) reported having maintained the WL for more than 1 year.

More than half (55%) of PwO were employed; among these, 12% reported that their employer offered “nutrition coaching,” 9% reported “healthy food options,” and 6% reported “onsite diet programs.” Additionally, 13% of PwO reported that their employer offered “insurance coverage for the medical treatment of obesity.”

HCP survey results

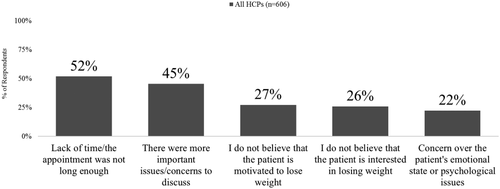

Figure 2 illustrates top reasons cited by HCPs as to why they might not initiate discussions about WL. “Lack of time/the appointment was not long enough” was selected most often (52%), followed by other “more important issues and concerns” (45%) (see Supporting Information Table S4 for full list).

Top five reasons HCPs may not initiate discussion about weight loss. All HCPs (n = 606). HCPs, health care providers.

More than 50% of HCPs considered obesity at least as serious as most other health conditions, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and congestive heart failure (Supporting Information Figure S6). They believed patients who are classified as overweight to class III obesity are likely to live 4 to 17 years less, respectively, than patients with healthy weight.

Sixty-seven percent of HCPs said they typically initiated weight management discussions; thirty-three precent indicated that their patient brought it up. Sixty-seven percent of HCPs reported being “very comfortable” or “extremely comfortable” talking with PwO about weight management, whereas thirty-three percent reported being “somewhat comfortable” or “a little comfortable.” When describing treatment options, HCPs reported recommending “general improvements in eating habits/reducing calories” and “generally being more active/increasing physical activity” to a large proportion of patients in need of weight management (58% and 57%, respectively). Other specific treatment options were recommended to fewer patients, including “counseling or lifestyle modification” (32%), “visiting a nutritionist or dietician” (27%), “prescription WL medication” (11%), “visiting a WL specialist” (nonsurgical) or “WL clinic” (9%), “over-the-counter WL medications” (4%), and “WL surgery” (7%).

HCPs reported that they “always” (28%) or “most of the time” (41%) recorded an “overweight” or “obesity” diagnosis in the medical record. Of those who did not say “always” or “most of the time” (31%), 43% reported providing a verbal diagnosis.

ER survey results

Similar to HCPs, more than half of ERs considered obesity at least as serious as most other conditions (Supporting Information Figure S7). ERs were asked about the type of wellness programs currently offered by their company, though not programs that are obesity specific. More than three-quarters (77%) reported that their company provided health and wellness information to their employees. Provision of healthy food options and nutrition coaching were reported by less than half of ERs (44% for both); provision of on-site diet programs was reported by 16%.

Employer wellness programs were reportedly motivated by numerous factors, including to “reduce insurance premiums/claims” (75%), “promote healthy behaviors among employees” (72%), “improve the physical well-being of employees” (70%), “support the well-being of employees and their families” (61%), and “improve work productivity” (53%).

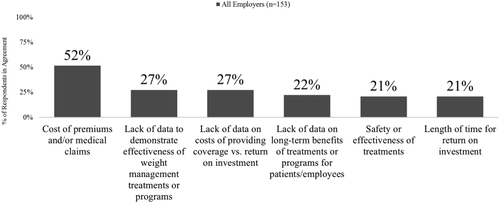

Figure 3 shows concerns ERs expressed about offering insurance coverage for obesity management. The primary concern, “costs of premiums and/or medical claims,” was endorsed by 52% of ERs. The next most commonly reported concerns were lack of data regarding return on investment, treatment efficacy, and long-term treatment benefits.

Employer concerns about offering insurance coverage for obesity management. All employers (n = 153).

Divergent behaviors and attitudes potentially creating barriers to obesity care

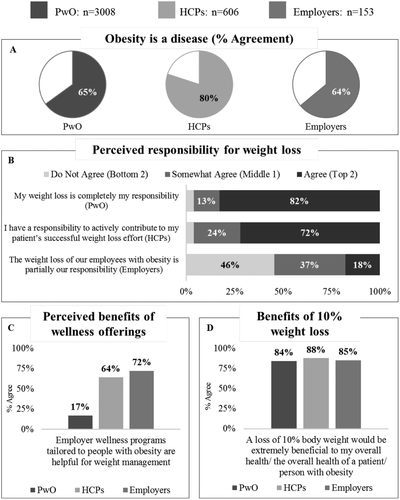

The panels in Figure 4 describe some key comparisons between respondent groups. Agreement that “obesity is a disease” was most prevalent among HCPs (80%), whereas PwO (65%) and ERs (64%) were less likely to agree. In ascertaining perceived WL responsibility, 82% of PwO believed it was completely their own responsibility. Seventy-two percent of HCPs reported that they (HCPs) had a responsibility to actively contribute to their patients' WL. In contrast, nearly half of ERs (46%) disagreed with the statement that employers have at least partial responsibility for employee WL. However, there was agreement among all groups that a 10% WL would be beneficial to overall health. A substantial disparity existed in perceived effectiveness of employer wellness programs tailored to PwO. Although 64% and 72% of HCPs and ERs, respectively, reported that they are helpful, only 17% of PwO agreed.

PwO, HCPs, and employer key comparisons. PwO, people with obesity; HCPs, health care providers.

Although the majority of HCPs (93%) and ERs (78%) felt that a person's weight would affect their health in the future “a lot” or an “extreme amount,” PwO were less likely to report this concern about their own weight (54%). Perceived barriers to PwO initiating WL were similar among all respondent groups (Table 2). Across all three study groups, “lack of exercise” was the most agreed-upon barrier to initiating WL efforts. “Lack of motivation” was the second-most-cited reason among PwO, whereas “preference for unhealthy food” was cited relatively more frequently among HCPs and ERs. “Controlling hunger” was also a frequently mentioned reason. See Supporting Information Table S5 for a comprehensive list of cited reasons.

| PwO | HCPs | Employers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 3,008), N (%) | (n = 606), N (%) | (n = 153), N (%) | |

| Lack of exercise | 1,853 (66) | 528 (87) | 127 (83) |

| Lack of motivation | 1,445 (51) | 432 (71) | 99 (65) |

| Preference for unhealthy food | 1,365 (49) | 500 (83) | 115 (75) |

| Controlling hunger | 1,377 (49) | 367 (61) | 70 (46) |

| Cost of healthy food | 1,169 (42) | 287 (47) | 64 (42) |

- PwO, people with obesity; HCPs, health care providers.

PwO and HCPs diverged on reasons for PwO not seeking obesity care. Among PwO who had not sought help from their HCP, the top two reasons cited (Table 3) were a belief that managing their weight was their own responsibility (44%) and that they knew what was needed to manage their weight (37%). In contrast, the primary reason cited by HCPs was PwO's embarrassment (selected by HCPs at a rate far higher than by PwO—65% vs. 15%, respectively). A full list of the reasons PwO do not seek help and reasons HCPs gave for PwO not seeking help are provided in Supporting Information Tables S6 and S7, respectively.

| PwO, not seeking treatment | |

|---|---|

| PwO-provided reasons | (n = 823), N (%) |

| I believe it is my responsibility to manage my weight | 362 (44) |

| I already know what I need to do to manage my weight | 308 (37) |

| I do not have the financial means to support a weight loss effort | 186 (23) |

| I do not feel motivated to lose weight | 173 (21) |

| I am embarrassed to bring it up | 128 (15) |

| HCPs, total | |

|---|---|

| HCP-provided reasons | (n = 606), N (%) |

| They are embarrassed to bring it up | 393 (65) |

| They do not feel motivated to lose weight | 337 (56) |

| They do not believe that they can lose weight | 333 (55) |

| They do not see their weight as a medical issue | 331 (55) |

| They are not interested in losing weight | 282 (47) |

- PwO, people with obesity; HCPs, health care providers.

Relatively few HCPs (9%) reported that they did not schedule follow-ups after discussing weight. In contrast, among PwO who discussed their weight with an HCP, 24% reported that a weight-related follow-up appointment was scheduled. Both HCPs and PwO reported that these follow up visits were not always kept. Only 4% of HCPs reported patients “always” kept follow-up appointments and half of HCPs (49%) reported that patients kept follow-up appointments “most of the time.” More than 95% either have kept or intended to keep the follow-up appointment.

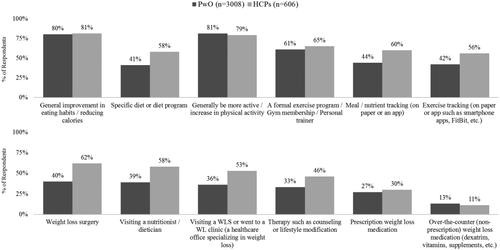

Most PwO and HCPs agreed that general eating improvements and increases in physical activity are “completely effective” for long-term weight management. For most other treatments, such as nutrition/exercise tracking, nutritional counseling, medication, and surgery, HCPs perceived greater effectiveness than PwO (Figure 5).

Perceived efficacy of weight loss treatments. Percent reporting that treatment is “completely effective.” PwO, people with obesity; HCPs, health care providers.

Discussion

The ACTION study highlighted current obesity perceptions and differed from other studies in its inclusion of three stakeholder groups, PwO, HCPs, and ERs. Viewing these perceptions from the vantage point of three key stakeholders, we found differences in attitudes about underlying cause(s) and appropriate treatment of obesity. Despite general consensus that obesity is a disease, the strong belief held by PwO that WL is their responsibility combined with their relatively low concern about the impact of weight on future health may contribute to their not seeking medical care for it. Lack of formal obesity diagnoses, low prioritization of WL discussions by HCPs, lack of follow-up care, divergent beliefs between PwO and HCPs about obesity treatment effectiveness, and low perceived value of employer wellness programs among PwO may also impact successful weight management.

Most (80%) HCPs recognize that obesity is a chronic disease with an impact on health and life expectancy, but fewer PwO and ERs recognize obesity's seriousness. Only about half of PwO believe an individual's weight could negatively impact future health, considerably less than reported by HCPs and ERs. Most (82%) PwO feel reducing their weight is their responsibility. However, as the majority of HCPs feel they have a responsibility to contribute to their patients' WL efforts, this could be an opportunity to help encourage HCPs take a more active role in facilitating obesity-related discussions with their patients.

Perceived WL barriers are similar among all three respondent groups, with lack of exercise and motivation most commonly cited. However, there is lack of alignment regarding reasons why PwO may not seek obesity care from HCPs. HCPs are more likely to view PwO as unmotivated to lose weight or too embarrassed to discuss their weight than PwO are to report this about themselves. PwO report not initiating conversations about their weight primarily because of the belief that managing their weight is their own responsibility and that they already know what is needed to be successful.

Although obesity is generally perceived to be a disease, it is not typically treated as such. Discussion of weight management tends to be deprioritized among HCPs, despite the negative impact on quality of life and longevity. Even when weight is discussed, just over half of PwO report receiving a diagnosis of obesity, which is often not documented.

Further, once WL conversations occur, follow-up care is not routine, with only about one-quarter of PwO reporting that a follow-up appointment is scheduled. This may be partly due to HCP perceptions of a lack of time in daily practice to address obesity.

When ascertaining perceived treatment effectivness, lifestyle interventions (healthy eating and physical activity) are considered more useful than medical management among both PwO and HCPs. However, HCPs have more confidence in surgical interventions and the benefits of specialized nutrition or therapeutic counseling than PwO.

Lastly, PwO widely perceive that employer wellness programs have limited value, as compared with the value reported by ERs and HCPs. Employer perceptions of the relative cost-effectiveness of available medical treatments and insufficient quality and quantity of data demonstrating treatment effectiveness may limit insurance coverage for obesity management.

Strengths

This study utilized a broad-based approach to query large samples of three key participants in decision-making about health care. Integration of the perspective of PwO, HCPs, and employers has been lacking in previous studies that have tried to address the barriers to effective obesity care at a provider or system level (25, 26). The surveys used in this study were designed to cover a broad range of obesity-related topics that could help identify and characterize attitudes and barriers to effective obesity management. The robust stratified sampling strategy used in this study enhances the generalizability of the results.

Limitations

Survey research can be susceptible to measurement errors; the cross-sectional design and self-reported nature of height and weight are potential limiting factors. Many studies have supported the conclusion that self-reported height and weight underestimates BMI (27). Thus, with the inclusion criterion of BMI ≥ 30 calculated from self-reported height and weight, the actual BMI of subjects enrolled in this study are likely to skew somewhat higher across the study population. The study's response rate, between 10% and 20%, may be considered a limitation, as well as the survey durations, which exceeded 37 minutes. However, comparison with the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (28) shows very similar distributions among various PwO characteristics and demographics, including BMI, age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, and marital status. While strong response rates are important in helping to reduce selection bias, our stratified sampling approach likely mitigates overrepresentation among any one PwO group as related to demographic factors. Finally, as this research was exploratory in nature, statistical testing may have revealed differences not otherwise found using multiple testing procedures.

Conclusions and implications

Some of the attitudes and barriers revealed in this study are likely modifiable, and correcting them should yield greater opportunities for more effective obesity management. Although a cause-and-effect relationship cannot be assumed for each barrier identified, these data provide directions for future research necessary to reduce or overcome these barriers. Obesity pathophysiology and management are often absent from health professional school curricula, rendering most HCPs ill equipped to address this problem. HCPs often recognize this limitation, but there are few incentives to remedy it. Exacerbating the problem, effective treatment of obesity is challenging, time-consuming, and poorly reimbursed, for both provider and patient. In the face of a large professional information gap, myths and misinformation abound. The perceptions and behaviors observed in this study reveal a broad, unmet opportunity to educate HCPs, PwO, ERs, and other stakeholders about the biology of obesity and the opportunity, value, and need of professional health care-based interventions. Overcoming major barriers to patients' seeking and receiving care is a necessary prerequisite to effectively addressing downstream barriers, whether from inadequate quality of care or limited effectiveness of available therapies. Strategies developed by collaborative efforts among PwO, HCPs, and ERs will likely lead to a better understanding of obesity itself, and the resulting solutions are more likely to be embraced, implemented, and ultimately successful.

A possible first step to changing perceptions and treatment practices for obesity is to further educate HCPs, PwO, and ERs about the biology, chronicity, and overall health impact of the disease. Informing HCPs about the real barriers for PwO not discussing weight concerns could reduce the reluctance among HCPs to proactively initiate these important conversations. HCPs also need to be encouraged to schedule follow-up visits focusing on the obesity diagnosis, given patients' inclination to keep these appointments. Finally, there is an opportunity to increase understanding among ERs that obesity can be effectively treated as a disease, potentially helping them design better wellness programs and more rigorously assess their effectiveness.