An integrative review of supportive relationships between child-bearing women and midwives

Abstract

Aims

To review and evaluate the literature on the factors related to developing supportive relationships between women and midwives, including facilitators and barriers.

Design

An integrative review.

Method

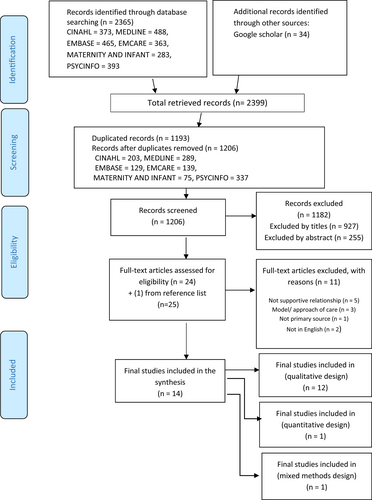

The search used CINAHL, MEDLINE, Embase, EMcare, Maternity and Infant Care, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar from January 2009–June 2020. Two reviewers screened the eligible studies, and 2,399 records were identified. Quality was assessed with the mixed methods appraisal tool, and 14 articles were included.

Results

The findings highlight that successful relationships require therapeutic communication, trust, respect, partnership, and shared decision-making. Supportive relationships improve women′s satisfaction and birth outcomes, and continuity of care model is an enabling factor. Further research is required to understand supportive relationships in non-continuity of care models and when different cultural backgrounds exist.

What Is Known About This Topic?

- The physical and emotional support midwives provide to child-bearing women can contribute to positive child-bearing experiences and birth outcomes.

- Not all women perceive their relationships with midwives as supportive.

- Organizational factors, such as staffing ratios and workload issues, may impede midwives' abilities to build supportive relationships with women.

- Continuity of care models facilitate the development of supportive relationships.

What Does This Paper Add?

- Midwives can facilitate the development of supportive relationships, through effective communication skills, mutual trust, respect, and partnership.

- Workplace culture within maternity units, affects midwives' abilities to develop and maintain supportive relationships with women.

- The socio-cultural context in which women and midwives live and work further impacts their abilities to develop and maintain supportive relationships.

- There is a lack of knowledge about how supportive relationships are developed in maternity units, especially where continuity of care is not practised.

What Are the Implications for Practices and Policies?

- More research is needed to explore the best approach and most effective strategies for developing supportive relationships, within existing models of care.

- Further research is required to understand how the cultural identities of both women and midwives affect the development of supportive relationships.

1 INTRODUCTION

A key aspect of maternity care is a supportive relationship between the child-bearing woman and her midwife or maternity nurse—the quality of this relationship is pivotal to safe maternity care and improving the woman′s experience (Agostini et al., 2015). Child-bearing experiences can vary greatly among women. A poor experience can affect a woman′s physiological and psychological wellbeing during the immediate postpartum and long-term periods (McInnes et al., 2020). Understanding how supportive relationships develop, between child-bearing women and their midwives or maternity nurses during the child-bearing period can help guide practices and improve maternity care.

2 BACKGROUND

The child-bearing period can be one of the most significant times in a woman′s life. In this review, the ‘child-bearing period’ refers to the pregnancy, labour, birth and postpartum period (i.e., up to 6 weeks following the birth) (Qi & Creedy, 2009, p. 2). During this time, many physiological, psychological and emotional changes can affect the woman′s emotional and physical well-being as well as the birth outcomes for her baby. A supportive relationship is a fundamental aspect of quality care for patients. In maternity care, supportive relationships between women and their midwives or maternity nurses are founded on mutual respect, shared power, and working in partnership to support women to engage in decision-making regarding their care (World Health Organization, 2016).

The literature has used various terms for healthcare providers supporting child-bearing women. In this review, “midwives” includes midwives and nurse-midwives caring for women giving birth and their infants, and preparing them for self-care and child care at home. It also includes registered or accredited nurses with a significant role in assessing and managing women′s progress in labour, where the provider attends the birthing room when the birth is close or there are serious complications. The exception is the “Results” section, where the original terminology from the reviewed articles is used for clarity.

Research has indicated that the physical and emotional support provided in a therapeutic relationship can contribute to positive child-bearing experiences and birth outcomes, including reduced oxytocin requirements and perineal lacerations (Sehhatie et al., 2014), reduced elective caesarean births, lower healthcare costs (Tracy et al., 2014), reduced incidences of postpartum depression and increased levels of satisfaction with care (Backstrom et al., 2016; Goodwin et al., 2018). Furthermore, an effective supportive relationship can lower a woman′s stress levels and facilitate optimal conditions for the baby′s development (Buckley, 2015).

Literature has suggested that certain factors affect the development of supportive relationships, such as ethnic heterogeneity, socioeconomic differences, culture and preferences (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Goodwin et al., 2018). Other factors include the healthcare professional′s capacity for empathy, trust, and emotional support, and the hospital′s policies for the maternity care model such as continuity of care (COC) (Bradfield et al., 2019b). COC is a model of midwifery care where the woman receives COC from a known midwife or known midwifery team throughout the child-bearing period, and postpartum care may continue in the home (Homer, 2016).

The importance of woman–midwife relationships has been the focus of research on models of maternity care that implement COC in their health systems, such as the United Kingdom (UK) and New Zealand (NZ) (Bradfield et al., 2019d; Homer, 2016). However, there is a paucity of summarized evidence focusing on facilitators and barriers to developing supportive relationships. An integrative review is required to synthesize the evidence on developing supportive relationships between child-bearing women and midwives. Such understanding can help build supportive relationships, and thus improve the quality of maternity care and women′s child-bearing experiences.

3 AIM

This review aims to evaluate the literature on the factors related to developing supportive relationships between women and midwives, including facilitators and barriers.

4 METHODS

4.1 Design

An integrative literature review design was used to understand a particular phenomenon and produce new knowledge in social and behavioural sciences (Torraco, 2016). Its flexibility in combining diverse methodologies, and ability to contribute to evidence-based practice can build knowledge and inform policymakers about a particular phenomenon in practice. This review adopted Whittemore and Knafl′s (2005) five-stage process: (1) identifying the research questions; (2) conducting a comprehensive search of the literature; (3) evaluating the studies found; (4) analysing the studies included in the review; and (5) reporting and discussing the findings.

4.1.1 Research questions

- What are the perceived facilitators and barriers to developing supportive relationships during the child-bearing period from women′s and midwives′ perspectives?

- What cultural factors might affect the process of developing supportive relationships during the child-bearing period from women′s and midwives′ perspectives?

4.2 Comprehensive literature search

The literature search was limited to publications from January 2009–June 2020. The search included studies from the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMbase, Emcare, Maternity and Infant Care, and PsycINFO. Google Scholar was used to find relevant studies. The keywords were: midwife*-woman relationship, and matern* or midwife*, and facilitators or barriers and experience. Words were combined with AND or OR to focus or limit the search results. Synonyms of each keyword were generated via word expansion (see Table 1).

| Keywords | Word expansion |

|---|---|

|

Midwife* or matern* |

(Midwifery or maternity or Maternal* or “obstetric* nurs*” or birth or ‘childbirth′ or childbear* or ‘child bear*’ or perinatal) |

| Midwife*-woman relationship | ((‘matern* nurs*’ or midw*) and woman and (relation* or interact* or supportive or relationship)) |

| Facilitator or barrier | (barrier* or obstacle* or challenge* or difficulties or facilitat* or impede* or hinder* or hindran*) |

| Experience | (experience* or opinion* or perception* or ‘womens voice*’) |

| The keywords used for Google Scholar | (Midwif* or maternity or Maternal* or obstetric* nurs* or ‘child bear*’) and (relation* or interact* or supportive or relationship) and (facilitator or barrier) and (experience* or perception* or women′s voice*) and (Saudi*) |

The inclusion criteria included: (1) primary research studies on supportive relationships between women and midwives, or maternity nurses, using any research design; (2) studies published in the English or Arabic languages; and (3) studies published in peer-review journals. The exclusion criteria included (1) studies not in the English or Arabic languages (due to a lack of translation resources); (2) publications other than primary research studies, such as meta-analyses, dissertations, books, grey literature, conference abstract papers, reports, and commentaries; (3) studies focused on relationships with healthcare providers other than midwives or nurses; and (4) studies with a focus on a particular maternity or midwifery program, approach or care model.

4.3 Evaluating the studies

The initial search retrieved 2,399 sources. The duplicates were removed (n = 1,193), and the relevant studies were manually screened. A total of 1,182 articles were excluded because of the study focus, leaving 24 studies for review. One article that aligned with the inclusion criteria was found in the reference list of one of the studies from the search. Therefore, the final review, included 25 studies, which were assessed for relevance, quality, and results concerning the research questions. A second reviewer (a supervisor from the research team) affirmed the eligibility of the included studies. Finally, a total of 14 articles were reviewed. The PRISMA diagram (see Figure 1) illustrates the review search steps and outcomes (Moher et al., 2009). All reviewers discussed and agreed on the review outcomes.

4.3.1 Quality appraisal

The quality of the included studies was appraised using the mixed-methods appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT allows a judgement of the methodological quality of studies for various research designs (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies). One study was judged as being of low quality. However, it was included because of its relevance to the research questions. Table 2 summarizes the included studies using MMAT criteria.

| Study answers by Y “Yes” or N “No” to appraisal questions | Study design | S1 | S2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | The quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Backstrom et al., 2016 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

| Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019 | Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Bradfield et al., 2019a |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Bradfield et al., 2019b |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Carlton et al., 2009 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Crowther & Smythe, 2016 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Davison et al., 2015 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Goodwin et al., 2018 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Madula et al., 2018 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

McInnes et al., 2020 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Menage et al., 2020 |

Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

| Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020 | Qualitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Shimizu & Mori, 2018 |

Quantitative | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | High quality |

|

Aschenbrenner et al., 2016 |

Mixed-methods | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Low quality |

- Note: S1 and S2 = screening questions (for all types of study design): S1, Are there clear research questions?; S2, Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 = Methodological quality criteria described below for each design, Qualitative: 1, Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question?; 2, Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question?; 3, Are the findings adequately derived from the data?; 4, Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data?; 5, Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? Quantitative, nonrandomized: 1, Are the participants representative of the target population?;2, Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)?; 3, Are there complete outcome data?; 4, Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis?; 5, During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? Mixed-methods: 1, Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question?; 2, Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question?; 3, Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted?; 4, Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed?; 5, Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? (Hong et al., 2018).

4.4 Analysing the studies

4.4.1 Data extraction

A data extraction form (see Table 3) was used to extract the data from the reviewed articles, including the study description, methods, and results. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data for factors considered facilitators or barriers to developing supportive relationships. This involved reading the articles, searching for meaningful ideas, creating codes, identifying themes, organizing the themes, and naming them concisely to make sense for the reader (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Three main themes and nine sub-themes were generated (see Table 4).

| Author & country | Study design | Method & instrument | Participants | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Backstrom et al., 2016 Sweden |

Qualitative Explorative phenomenology |

Interviews | 15 women |

Professional support contributed to women's mental preparedness for childbirth and parenting. Factors affected midwives' support of women, including the presence of a continuum of care. |

|

Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019 Australia |

Qualitative Descriptive Phenomenology |

Interviews | 31 midwives |

Building a supportive relationship with women is essential to midwifery practice. Strategies to build a relationship with women in different models of care, including woman-centred approach. Organizational barriers to building connection with women Preparing the physical environment facilitates the connection with women. |

|

Bradfield et al., 2019a Australia |

Qualitative Descriptive Phenomenology |

Interviews | 10 midwives |

Building relationships and partnership with women by midwives through enabling rapid rapport and trust, which was facilitated by offering women-centred care. Organizational barriers existed to building supportive relationships, including the model of care. |

|

Bradfield et al., 2019b Australia |

Qualitative Descriptive Phenomenology |

Interviews |

10 midwives |

Building relationship with women is facilitated by the “known midwife” model and should be provided across the childbirth continuum. Respectful, professional relationships and the practice of being “with woman” enhanced midwives' ability to provide woman – centred care. Midwives experienced barriers to building a relationship with women in both known and unknown models of care. |

|

Carlton et al., 2009 USA |

Qualitative |

Interviews Field notes |

18 nurses | Facilitators and barriers to building a supportive relationship with women include organizational and individual factors of both providers and women. |

|

Crowther & Smythe, 2016 New Zealand |

Qualitative Phenomenology |

Interviews |

3 mothers 6 midwives, 3 ambulance crew 1 GP 1 obstetrician |

Relationships that are founded on mutual understanding and attuned to trust matter. Tension resulted from misunderstanding in relationships leading to discord among individuals and groups |

|

Davison et al., 2015 Australia |

Qualitative Modified grounded theory |

Interviews | 14 women |

Family centred care is an approach of equal power between the midwife, woman and family members. Women perceived the relationship is everything; that feeling in control is paramount to having a positive experience. |

|

Goodwin et al., 2018 UK |

Qualitative Ethnography | Interviews Observations |

9 women 11 midwives |

Family relationships have a negative impact on the midwife–woman relationship when dominates women′s decisions. The maternity care issues related to (family involvement, culture and health-care systems) influence the midwife–woman relationship. |

|

Madula et al., 2018 Eastern Africa |

Qualitative Descriptive | Interviews | 30 women |

Half the women participants reported good communication skills, while the other half of participants reported miscommunication and verbal abuse by maternity nurses/midwives. Linguistic barriers negatively affected building of supportive relationships. |

|

McInnes et al., 2020 UK |

Qualitative Descriptive |

Meeting Interviews Survey Published literature Field notes observation |

Stakeholders 366 midwives 89 women |

Trust building is the core to continuity of midwifery care. Maternity team relationships contributed to the improvement in the relationship between midwives and women in different models of care. Continuity of care helped midwives to provide full skillset across the childbearing continuum. |

|

Menage et al., 2020 UK |

Qualitative |

Interviews | 17 women |

Women experienced compassionate midwifery care through relationship and empowerment they experienced. Women perceived the ability of midwives to manage work conflicts impacting provision of compassionate care. |

|

Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020 Sweden |

Qualitative Explorative |

Focus group Interviews | 16 midwives |

Communication with immigrant pregnant women was influenced by women′s education and experiences. Midwives were able to build a trustful relationship with even though language was a barrier between them. Cultural difference was associated with communication difficulties between midwives and women, in particular, the influence of the woman′s family. Cultural competencies and organizational support are required to help midwives in their roles, despite the strategies developed by them to cope with work challenges. |

|

Shimizu & Mori, 2018 Japan |

Quantitative |

*NICU scales questionnaire | 98 mothers |

Mothers' experiences were positive and linked to better mother-nurse relationship. Maternity nurses were able to provide care to mothers and parents based on their individual needs. Positive relationships between maternity nurses and women lead to building of trust. |

|

Aschenbrenner et al., 2016 USA |

Mixed-Methods Cross-sectional descriptive |

Online questionnaire | 60 nurses |

Maternity nurses' attitudes towards building supportive relationships are affected by their personal experiences. Organizational and maternal barriers to building a supportive relationship with birthing women exist. |

| No. | Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human interaction factors |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

| 2 | Cultural factors |

|

|

||

| 3 | Organizational factors |

|

|

||

|

4.5 Reporting and discussing the findings

4.5.1 Study characteristics

Two studies were conducted in the United States of America, three in the UK, two in Sweden, one in Japan, one in East Africa, four in Australia and one in NZ. There were 762 participants in the reviewed studies, including 450 midwives, 78 maternity nurses, 172 child-bearing women and 101 mothers. Of the participating women (i.e., 273 child-bearing women and mothers), 22 participated in the studies during pregnancy, 17 were in either the pregnancy or postpartum period, 234 were in the postpartum period and one was in a neonatal intensive care unit (Shimizu & Mori, 2018).

5 RESULTS

5.1 Theme 1: Human interaction factors

Human interaction factors were mentioned in 14 studies. Four sub-themes emerged: demonstrating trust and respect, recognizing midwives' attitudes and beliefs, developing partnerships and effective communication skills.

5.1.1 Demonstrating trust and respect

Six qualitative studies (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Madula et al., 2018; McInnes et al., 2020; Menage et al., 2020) described trust and respect as a facilitator of developing supportive relationships with women. In this review, ‘respect’ refers to how midwives differentiate the boundaries between professional and personal relationships, including accepting women′s choices (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2018). “Trust” is defined as the part of a partnership with a woman that maintains equality and sharing (International Confederation of Midwives, 2017; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2018).

Midwives stated that trust promoted the building of supportive relationships with women (Menage et al., 2020), and showing respect allowed them to form a strong connection, during a challenging time to engage, such as labour. In a study including 15 child-bearing women, the importance of respect was reinforced—they experienced positive relationships with maternity nurses when they felt respected (Madula et al., 2018).

5.1.2 Recognizing midwives' attitudes and beliefs

“Attitudes” and ‘beliefs’ refer to modes feeling and thinking, which affect behaviour and, therefore, the ability to develop relationships (Bradfield et al., 2019a; Carlton et al., 2009). Three qualitative studies (Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b) reported that midwives' negative or positive feelings were important for their attitudes towards developing supportive relationships with women. Eight articles (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009; Goodwin et al., 2018; McInnes et al., 2020; Menage et al., 2020) discussed facilitators or barriers influencing midwives' or maternity nurses' attitudes. These included motivation, personality, preference, experience and knowledge (McInnes et al., 2020).

Experience and knowledge can empower midwives to manage challenges while building supportive relationships. The more educated and/or experienced the midwives/maternity nurses, the more their relationships were (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019a; Carlton et al., 2009; Menage et al., 2020). Further, when a midwife′s and a woman′s personalities do not match, it could impede the supportive relationship (Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019a). However, neither study discussed how the personalities might be mismatched.

5.1.3 Developing partnerships

Partnerships were discussed in 10 studies. Carlton et al. (2009) found that partnerships could be achieved when women and maternity nurses shared power. Partnerships include elements such as shared decision-making (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b), mutual involvement (Shimizu & Mori, 2018) and healthcare professionals advocating for empowering the woman (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Davison et al., 2015; Shimizu & Mori, 2018). Empowering child-bearing women is considered essential in supportive relationships (Menage et al., 2020). It is thought to occur when the midwife provides guidance (Crowther & Smythe, 2016) and advocates for the woman (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019). However, there were few details about when to share decision-making and the relevant aspects of the care.

Two qualitative studies (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Davison et al., 2015) asserted that woman-centred care could enhance positive and supportive relationships with women, facilitate shared decision-making and improve their birth outcomes, enhancing women′s satisfaction with care and birthing experiences. Seven studies (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a; Davison et al., 2015; Goodwin et al., 2018; McInnes et al., 2020; Menage et al., 2020; Shimizu & Mori, 2018) also reported that woman-centred care that was tailored to the woman′s preferences facilitated supportive relationships .

Other studies identified positive relationships between women and midwives when women, their family members and significant others were involved in care planning (Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Davison et al., 2015; Goodwin et al., 2018; Shimizu & Mori, 2018). Shimizu and Mori′s (2018) study was conducted in Japan with a small sample size (N = 98). Although all study participants assessed their relationships with maternity nurses positively, Shimizu and Mori stated that it might not have been positive for those who did not participate. Furthermore, the women′s responses remained positive even when the questions did not apply. Finally, two studies (Bradfield et al., 2019a; Goodwin et al., 2018) reported that some women refused to choose or build any relationships and preferred their own space.

5.1.4 Effective communication skills

Effective communication skills are fundamental in any relationship. Nine articles (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009; Crowther & Smythe, 2016; Madula et al., 2018; Menage et al., 2020; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020) identified communication as an enabling practice for developing supportive relationships with women. In one study, midwives (n = 31) described how they used basic communication skills, such as gaining rapport and providing verbal encouragement, to facilitate relationships development with women (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019). Further, Backstrom et al. (2016), Oscarsson and Stevenson-Ågren (2020) and Menage et al. (2020) found that active listening skills are essential to developing supportive relationships. However, Madula et al. (2018) reported that a lack of interpersonal skills in midwives and maternity nurses was a common communication barrier leading to the women feeling frustrated about their unmet needs.

5.2 Theme 2: Cultural factors

Five studies (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a; Carlton et al., 2009;Goodwin et al., 2018; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020) discussed cultural factors, focusing on individual′s beliefs and, their effects on the expectations and practices of women and midwives.

5.2.1 Women′s health beliefs

Bradfield et al., 2019a described the need for cultural safety, and understanding of women′s cultural backgrounds in the practice of maternity care, which requires trust and respect for other cultures. Two studies found that women and midwives valued supportive relationships, highlighting the importance of keeping this relationship non-judgmental to facilitate its building, especially in women and midwives with different cultural beliefs (Goodwin et al., 2018; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020). Oscarsson and Stevenson-Ågren (2020) reported that women′s health beliefs affected their child-bearing practices, especially when they differed from midwives′ beliefs, all midwives in Oscarsson and Stevenson-Ågren′s study were Swedish, which may have affected the results because cultural diversity can affect midwives′ perceptions and experiences. The study also did not report the cultural beliefs of immigrant women, although they were not homogenous. Furthermore, one study in the UK (Goodwin et al., 2018) claimed that midwives tended to negatively judge Pakistani women when they were unaware of their cultural practices and beliefs, such as shaving a newborn′s head. Unfamiliarity with women′s beliefs, priorities and expectations was a barrier to developing supportive relationships (Goodwin et al., 2018).

5.2.2 Family involvement

Goodwin et al. (2018) reported that family dynamics in some cultures (e.g., Pakistani) significantly influenced the relationships between maternity nurses and women. Maternity nurses and midwives explained that family members influenced some women′s decisions and the dominant family member was often the decision-maker (Carlton et al., 2009; Goodwin et al., 2018; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020). Extra attention to cultural influence on building supportive relationships was considered as a facilitator (Goodwin et al., 2018). Conversely, one study described how some women preferred to handle the labour and birth alone and not involve their partners, preferring to handle the labour and birth alone (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019).

5.3 Theme 3: Organizational factors

Ten studies identified the organizational factors, such as the model of care, work-load and resources, for developing supportive relationships with child-bearing women. Three sub-themes emerged: COC, time/workload and physical environment.

5.3.1 Continuity of care

Eight studies reported that (COC) facilitates developing supportive relationships with women. Healthcare model differ between countries, influencing the type and extent of COC the maternity team provides. This review included different healthcare systems in which the studies were conducted. Some studies mentioned COC in the health systems in the UK (McInnes et al., 2020; Menage et al., 2020), Australia (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a; Davison et al., 2015), Sweden (Backstrom et al., 2016; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020), and NZ (Crowther & Smythe, 2016). Other studies have reported non-COC in systems, in the United State of America (Carlton et al., 2009) and Australia (Bradfield et al., 2019b).

Women and midwives in three qualitative studies (Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019b; McInnes et al., 2020) reported that COC in maternity services facilitates supportive relationships and trust. Additionally, Oscarsson and Stevenson-Ågren (2020) and Menage et al. (2020) suggested that midwives who cared for the same women throughout their pregnancies were more likely to build trusting relationships. However, midwives working in a birthing unit where COC was not practised expressed a feeling of disconnection with women (Bradfield et al., 2019b). Women in one study (Davison et al., 2015) wanted COC and preferred private midwifery care because the relationship with their midwives was as supportive as they needed and they could be involved in shared decisions. This study was conducted in one location in Australia (from 2007–2013) when support for publicly funded home birth was still being developed.

5.3.2 Time and workload

The literature highlighted several work situations as barriers to supportive relationships with child-bearing women; including lack of adequate time (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009; Madula et al., 2018), heavy workloads (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Bradfield et al., 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009; Menage et al., 2020), and staff shortages (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Carlton et al., 2009). Maternity nurses felt distracted by paperwork and technological interventions, such as electronic fetal monitoring and high-risk protocols for all admitted women (Carlton et al., 2009). Carlton et al. (2009), Bradfield et al., 2019b and Crowther and Smythe (2016) found that midwives felt overloaded and often had to deal with staff shortages, which affected their abilities to provide care and develop relationships. Maternity nurses also reported a lack of time for developing supportive relationships with women due to their working conditions (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Carlton et al., 2009). Maternity nurses were challenged when they had to balance keeping electronic health records (EHRs) and women′s needs, such as electronic fetal monitoring (a part of HER), resulting in decreased time for building relationships (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Menage et al., 2020).

5.3.3 Physical environment

This sub-theme refers to organizational facilitators and barriers to providing resources and support for midwives to develop supportive relationships, which midwives considered a significant challenge to staying connected with women (McInnes et al., 2020). For example, birthing unit design can influence how women feel. Birthing room environments have varying levels of privacy, lighting, music or silence and hygiene facilities (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019). When the design matches a woman′s preferences, promotes a positive relationship between the woman and the midwife (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Menage et al., 2020). This can improve women′s physical and psychological comfort, enabling supportive relationships and positively affecting women′s feelings (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Carlton et al., 2009; Menage et al., 2020).

6 DISCUSSION

This review has provided evidence on the factors related to developing supportive relationships between women and midwives. The findings indicated that midwives' relationships with child-bearing women are critical and depend on human interaction, cultural and organizational factors. Each factor will be discussed as a facilitator or barrier to developing supportive relationships during the child-bearing period from women′s and midwives′ perspectives.

6.1 Factors

6.1.1 Human interaction

Developing supportive relationships with child-bearing women requires mutual trust, respect, partnerships and attitudes and effective communication skills, all of which are interrelated and facilitate relationships. Partnerships allow women to feel empowered to share decision-making and make their own choices. They require provisions for involvement and advocacy (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Shimizu & Mori, 2018). Although some studies (Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Davison et al., 2015; McInnes et al., 2020; Shimizu & Mori, 2018) identified involvement as a part of partnerships with child-bearing women, there is insufficient information regarding the process for encouraging such involvement. Some studies focused on partnership as a maternity care approach, a foundational premise in developing supportive relationships (Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009). However, these studies did not demonstrate the steps necessary to build partnerships with women and thus, facilitate relationships. This area requires further research.

Appropriate shared decision-making and women′s involvement were not always present in the reviewed studies (Bradfield et al., 2019a, 2019b; Davison et al., 2015; Shimizu & Mori, 2018). Thus, there was little information about decision-making processes, including how, when and the degree to which women were involved in decision-making, which could be considered a barrier to building supportive relationships. Additionally, there was a lack of information about women′s understanding of empowerment, which may indicate their readiness to make their own decisions. While midwives should employ a woman-centred care approach, empowering women to participate in joint decision-making (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, 2018), further research should clarify women′s understanding of empowerment.

Two studies reported described how midwives' or maternity nurses' attitudes, including their personalities, knowledge and experience, affected how they valued developing supportive relationships with women during childbirth (Bradfield et al., 2019a; Carlton et al., 2009). Midwives need to gain women′s trust through positive attitudes and respect for their individual needs and culture.

These human interaction factors will have little success without effective communication skills, which are the basis of relationship development (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016; Backstrom et al., 2016; Bradfield, Hauck, Duggan, et al., 2019; Bradfield et al., 2019b; Carlton et al., 2009; Crowther & Smythe, 2016; Madula et al., 2018; Menage et al., 2020; Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020). Positive communication between healthcare professionals and women facilitates trust, respect and support (Backstrom et al., 2016). Therapeutic communication should be supported and practised more often to meet women′s needs and facilitate relationship development (Fenton & Jones, 2015; World Health Organization, 2019).

6.1.2 Culture

The reviewed studies suggested some cultural factors, such as women′s health beliefs (Carlton et al., 2009; Goodwin et al., 2018), and family involvement (Oscarsson & Stevenson-Ågren, 2020) that might inhibit the effective communication needed to support the connection between women and midwives. For example, some studies found women had a different view from that of midwives—while midwives often viewed the control of family members as a negatively dominant influence, some women viewed that as a kind of support (Goodwin et al., 2018). Such a situation requires that midwives understand cultural influences to maintain supportive relationships in a preferred way.

Further, women from different cultures might present with varying health demands (Tehsin et al., 2018), and the cultural barriers can affect supportive relationships. Understanding women′s beliefs and culture can help midwives understand the reasons behind health practices, promote acceptance and facilitate supportive relationships. Therefore, assessing women′s expectations of maternity care can benefit relationship development.

However, the relevant literature included of 14 articles published over the last 10 years, from seven countries, with primarily Western cultures. Few studies focused on cultural factors that affect how supportive relationships develop, indicating a substantial gap in the literature. Country-specific studies are needed to explore cultural differences, views, expectations and health practices relevant to building relationships with child-bearing women.

6.1.3 Organization

This review indicates that COC is crucial to meeting women′s. Findings demonstrated that women and midwives prefer to know each other before child birth, preferably meeting during the antenatal period (Bradfield et al., 2019a), so their care can be continuous throughout the child-bearing period (McInnes et al., 2020). The familiarity between women and midwives has helped midwives understand women′s needs and identify changes in health statuses throughout their visits. Simultaneously, it has helped women feel more comfortable with their midwives and develop trusting and positive relationships (McInnes et al., 2020). This finding was supported by recent Cochrane reviews, which established COC as the gold standard for midwifery care and suggested it should be practised much more widely (Homer et al., 2019; Sandall et al., 2016). However, further studies should address how supportive relationships are enabled within maternity care environments with a non-COC model.

Findings have shown that midwives and maternity nurses are distracted by workloads due to documentation and technology interventions (Aschenbrenner et al., 2016). Developing a successful relationship requires a balance between all support aspects. Therefore, midwives desire enough time to build trust, respect and partnerships with women, particularly those from different cultures. They need extra time before, during and after meeting women to manage their increased workload (Kerr et al., 2014). One strategy for managing this challenge is more efficient documentation methods that enable more time and effort strengthening relationships with women (Kent & Morrow, 2014). Although the EHR might prompt workflows, several issues have been noted, such as ineffective time management and unexpected deficiencies in patient care and work flow (Abbey et al., 2012; Baumann et al., 2018). Thus, the effect of EHR on midwives' time needs more attention, suggesting staff training and EHR system modifications to increase the time available for women′s care (Coleman et al., 2021; Karp et al., 2019).

6.2 Strengths and limitations

This review integrated qualitative and quantitative studies to produce a holistic understanding of developing supportive relationships with child-bearing women. However, it excluded non-English and non-Arabic studies, therefore, relevant data may have been omitted.

6.3 Recommendations

Future research should develop strategies to facilitate supportive relationships, particularly in non-COC models. This review recommends that strengthening midwives' communication skills is essential. Future research should focus on how midwives share decision-making power with women throughout the child-bearing period, which is an important component of supportive relationships. Organizational support is a major factor affecting supportive relationships, and COC models are highly recommended. Further investigations should also address the effect cultural identity on relationship development and how women and midwives manage cultural differences.

7 CONCLUSION

This review highlighted that supportive relationships require therapeutic communication, trust, respect, partnership and shared decision-making. Developing supportive relationships with women is easier in COC models of maternity care. However, little is known about developing and maintaining supportive relationships in non-COC models. Further, working with women from different cultural backgrounds can affect developments, with additional considerations required to ensure women feel supported. However, it is unclear how supportive relationships are enabled within maternity care environments with differing cultural identity factors, demonstrating the need for further research.

7.1 Relevance to clinical trial

This study aimed to contribute substantially to evidence-based decisions about the organizational barriers to building supportive relationships. These findings could be used to review or develop nursing and midwifery education curricula, guidelines and policies to enhance the knowledge, skills and practices used to build supportive relationships with child-bearing women. Further, birthing outcomes can be improved, reducing health costs and increasing patient satisfaction. The importance of individualized care must be emphasized through the appropriate development of supportive relationships. This, will help midwives and maternity nurses understand and value women′s needs and ensure they have adequate time to build supportive relationships with women, provide woman-centred care and ultimately improve women′s experiences during the child-bearing period.

This review highlighted the importance of women′s involvement. Effective supportive relationships between child-bearing women and midwives, increase women′s involvement and autonomy in caring for themselves and their infants in postpartum and during early childhood. Thus, there is a need to improve midwives′ skills concerning why, what and how to begin women′s involvement, suggesting that reflective supervision methods during home visiting could help maintain boundaries, observe one′s reactions and improving involvement (Tomlin et al., 2016).

Continuity of care focuses on building supportive relationships with women, which requires supportive leadership, and enables midwives to stay connected with maternity team (McInnes et al., 2020). Thus, further research is needed to examine relationships between all organizational levels in the maternity care. Additionally, there are few details on the strategies midwives and maternity nurses use to build these relationships. Thus, further research should address midwives' and maternity nurses' priorities and the actual time required to develop supportive relationships with child-bearing women.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors agreed and had a primary contribution to the following: conception and design, data appraisal, extraction, analysis, and reporting of findings. They affirmed their approval of the final version to be published.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Debbie Booth, Senior Research Librarian (The University of Newcastle) for guidance in the literature search.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was completed as a part of PhD research project at The University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, New South Wales 2308, Australia. Grant number HREC H-2021-0217. PhD candidate Hadeer Almorbaty has held a scholarship awarded by Prince Sultan Military College of Health Sciences, Medical Services Division, Armed Forces, Ministry of Defence, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for her PhD study at the University of Newcastle, Australia. There are no other funding sources for this project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in [repository name] at [URL/DOI], reference number [reference number]. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: [list resources and URLs].