Patients' experiences of frequent encounters with a rheumatology nurse—A tight control study including patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Abstract

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that is treated with both pharmacological and nonpharmacological methods. The treatment works well for patients who are knowledgeable about their disease and situation. However, this may be different for others as, among other things, it depends on how well informed the patients are in relation to their condition. Available research primarily focuses on patients in remission. One way of supporting and strengthening the group who experience a lack of well-being due to their disease and providing them with increased knowledge about their situation can be to give them access to a nurse-led clinic based on person-centred care.

Aim

The aim of the study was to describe the experience of patients with RA attending person-centred, nurse-led clinics over a 12-month period.

Methods

A qualitative method was employed to deepen the understanding of the phenomenon. Fifteen participants were interviewed, and the text of the interviews was analysed using the phenomenographic method.

Results

The analysis resulted in three categories that described participants' experiences of their encounters with a nurse. The three categories describe a process with interrelated concepts: first, Encountering competence, followed by Experiencing a sustainable relationship and, finally, Making a personal journey.

Conclusion

Patients with RA who had frequent meetings with a nurse experienced being strengthened on several levels and having gained increased knowledge about their disease. The person-centred approach made them feel that they had been met on their own level, in accordance with their needs and level of knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory, incurable disease of the joints. It is characterized by pain, fatigue and functional impairment, and can flare up intermittently—for example, with increased disease activity. It can also lead to deterioration over time (Klareskog, Catrina, & Paget, 2009).

In Sweden, approximately 0.7% of the adult population have been diagnosed with RA. The disease can affect children, young persons and adults, although onset is typically between 45 and 65 years of age. It is 2–3 times more common among women than men (Klareskog et al., 2009). The cause is unknown, but some hereditary and environmental factors, such as smoking, are involved (Chang et al., 2014; Klareskog et al., 2009).

The symptoms may appear gradually but also acutely. The diagnosis of RA is based on general symptoms, laboratory diagnostics (including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein levels, rheumatoid factor levels), X-ray and joint examination, whereby swollen and painful joints are assessed. Early-stage RA may be difficult to diagnose, owing to the existence of several rheumatology differential diagnoses—for example, systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriatic arthritis (Klareskog et al., 2009).

The treatment and rehabilitation for patients with RA are both pharmacological and nonpharmacological. Early treatment is important for keeping disease activity at a low level, thereby reducing joint damage (Nam et al., 2010; Rantalaiho et al., 2010). To achieve this and provide optimal treatment, patients must have access to the whole rheumatology team—for example, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social welfare officers (Klareskog et al., 2009; Vliet Vlieland & van den Ende, 2011).

Patients' experiences of living with RA comprise striving to live as normal and good a life as possible and finding ways of coping with the disease in everyday life. This can involve accepting the disease, maintaining a positive attitude, making the best of the situation and coping with the symptoms. Patients describe trying to use their personal resources efficiently, in addition to enlisting help from others, such as family, friends and healthcare professionals (Bergsten, Bergman, Fridlund, & Arvidsson, 2011; Sanderson, Calnan, Morris, Richards, & Hewlett, 2011). Some patients report their struggle to cope with their RA, which may be due to their experience of not having a good relationship with care staff or doubting their own abilities (Bergsten et al., 2011).

Previous studies on nurse-led clinics for patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, have demonstrated that nurses are highly competent at educating and following up patients (Carey & Courtenay, 2007; Page, Lockwood, & Conroy-Hiller, 2005). It is well known that some patients find it easier to talk to a nurse than to a doctor and that this makes them feel safer, and more familiar with and involved in their own care (Bala et al., 2012; Larsson, Bergman, Fridlund, & Arvidsson, 2012). However, research on patients with RA appears to lag behind that in the above-mentioned studies. A review of articles focusing on patients with low disease activity found that nurse-led rheumatology care was deemed equivalent to standard care (Ndosi, Vinall, Hale, Bird, & Hill, 2011). However, the authors of the review stressed that nurse-led care was considered preferable in some studies but that there was insufficient evidence on this issue. Thus, more research in this area is necessary.

1.1 Previous study of a nurse-led clinic

A randomized controlled study (RCT) was conducted at a rheumatology clinic in a hospital in western Sweden. The study covered a 6-month period, with a follow-up after 12 months. The patients were randomized to an intervention group or standard care. The intervention had a clear focus on tight control and person-centred care aimed at controlling the disease activity. The patients randomized to the intervention group met with a nurse every 6 weeks. During these visits, patients' joint status and medication were discussed and adjustments made if necessary. Person-centred care presupposes a partnership between healthcare professionals and the patient. The planning of patient care and treatment is facilitated when each patient is encountered as a person, with their own identity, and allowed to tell their own story. The patient's story is central to the care process, and documentation is important when discussing person-centred care (Ekman et al., 2011). A health plan was also developed based on patients' statements about the goals of their visits, including exercise, relaxation and administration of medication. The health plan was evaluated at each visit.

The patients randomized to standard care followed the rheumatology clinic guidelines, which involved at least one annual visit to a doctor.

The primary outcome of the RCT was disease activity (28-joint disease activity score [DAS 28]) at 6 months. The patients in the intervention group who were assessed as having low disease activity (DAS 28 < 3.2) at 6 months discontinued the intervention and were evaluated after 12 months, whereas patients who did not exhibit low disease activity at 6 months continued the intervention for another 6 months. All patients ended the study after 12 months.

An interview study was performed in those patients who had taken part in the intervention performed in the afore-mentioned RCT study to explore their experiences of meeting the same nurses at regular intervals. As they had not previously had the opportunity to express their perceptions with regard to nurse-led, person-centred care, it was important to allow them to state whether they perceived that they had received the help they required in terms of medication adjustment, symptom relief and so forth.

The aim of the present study was to describe the experience of patients with RA attending person-centred, nurse-led clinics over a 12-month period.

2 METHODS

A qualitative method was employed to achieve a deeper understanding of participants' experiences of meeting with a nurse every 6 weeks over a 12-month period. A phenomenographic approach was chosen, as this method is suitable for describing participants' perceptions of their experiences.

Phenomenography aims to provide a deeper understanding of people's perceptions and their real-life experience. It is important to take a holistic view of the phenomenon, the person experiencing the phenomenon and other relevant contextual factors.

2.1 Phenomenography

Phenomenography is the study of the way in which different individuals experience a specific phenomenon by focusing on their real-life experience (Marton & Booth, 1997). The researcher seeks to identify patients' perceptions of the phenomenon under study, as all human beings experience a specific phenomenon differently (Marton & Booth, 1997). Phenomenography is concerned with how something appears to an individual, not how it really is (Marton & Booth, 1997).

2.2 Sample

A total of 70 patients participated in the previous RCT study. The intervention group comprised 36 patients who met with a nurse on a regular, frequent basis, and the control group comprised 34 patients who consulted a doctor. A strategic selection was performed on the 36 participants in the intervention group, in terms of age and gender, to spread the variance of perceptions due to these factors.

The nurse responsible for the study asked participants whether they were willing to participate in the study and be interviewed about their experiences of meeting with a nurse on a regular, frequent basis. In total, 15 patients were invited to participate, and all accepted.

Fourteen women and one man, aged between 21 and 79 years, were interviewed. The duration of living with RA varied between 2 and 40 years (see Table 1).

| participant | Gender | Age | Duration of the disease | Educational level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Woman | 59 years | 29 years | Upper secondary school |

| 2 | Woman | 65 years | 13 years | University education |

| 3 | Man | 64 years | 7 years | Upper secondary school |

| 4 | Woman | 60 years | 40 years | Upper secondary school |

| 5 | Woman | 79 years | 15 years | Upper secondary school |

| 6 | Woman | 61 years | 11 years | University education |

| 7 | Woman | 61 years | 8 years | Upper secondary school |

| 8 | Woman | 64 years | 40 years | Upper secondary school |

| 9 | Woman | 75 years | 18 years | University education |

| 10 | Woman | 79 years | 21 years | Primary school |

| 11 | Woman | 48 years | 8 years | Upper secondary school |

| 12 | Woman | 21 years | 5 years | Upper secondary school |

| 13 | Woman | 70 years | 2 years | Upper secondary school |

| 14 | Woman | 64 years | 3 years | University education |

| 15 | Woman | 55 years | 2 years | Upper secondary school |

2.3 Data collection

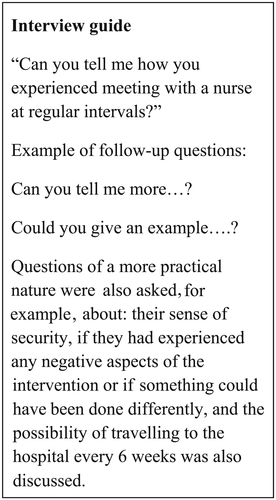

Individual interviews were conducted with the 15 individuals who had agreed to participate. Two pilot interviews were initially performed to ascertain whether some aspects of the interview situation required amendment and to see how the participants addressed the questions. As no adjustment proved necessary, these interviews were included in the analysis. The interviews took the form of a dialogue, with the same opening question for all participants: “Can you tell me how you experienced meeting with a nurse at regular intervals?” The follow-up questions varied, depending on participants' responses, and could concern whether their encounters with a nurse had given them a sense of security, whether they had experienced any negative aspects or if they believed that something could have been done differently. The practicality of travelling to the hospital every 6 weeks was also discussed (see Figure 1).

Participants were allowed to choose the time for the interviews (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009), which took place in a private room at the clinic. The interviewer (A.S.S.) wore casual clothes, in order to put participants at their ease.

The interviews, which lasted between 20 and 40 min, were tape-recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Field notes were also taken in connection with the recording, to minimize the risk of missing nonverbal cues. After each interview, notes were made about the interview as a whole and the atmosphere in which it took place, thus providing valuable information for the analysis (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009).

2.4 Data analysis

The analysis started during the transcription of the interviews, as a way of becoming familiar with the material and gaining a first impression of the information embedded in the text. Subsequently, the data analysis was carried out in seven steps, in accordance with the phenomenographic method presented by Sjöström and Dahlgren (2002).

The authors describe the first step as “becoming familiar” with the material—for example, by reading it several times. The second step involves identifying significant statements in each interview related to the aim. In the third step, the statements are compared, to identify variations. The fourth step comprises labelling and grouping the statements into meaning units. The fifth step involves comparing the similarities and differences between the meaning units, and differentiating them from each other. In the sixth step, the meaning units are labelled and sorted into categories. Finally, in the seventh step, the categories are compared and the special character of each category described (Sjöström & Dahlgren, 2002).

The analysis was carried out by the first researcher (A.S.S.) and the supervisor (U.B.), who initially worked individually in order to see what emerged. Consensus was sought as a means of increasing the reliability and validity of the study and to reduce the influence of researcher preunderstanding.

2.5 Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the regional ethics committee at Gothenburg University (855–13). participants were provided with both verbal and written information about the study, and their informed consent was obtained. They were advised that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study without having to give a reason. Confidentiality was guaranteed and it was emphasized that none of the participants would be identifiable. The interviewer was not involved in the care of the participants.

3 RESULTS

The analysis resulted in three categories that describe the participants' experiences of frequent encounters with a nurse during a 12-month period. Three categories emerged that describe a process with interrelated concepts: Encountering competence; A sustainable relationship; and Making a personal journey (see Table 2).

| Categories | Encountering competence | A sustainable relationship | Making a personal journey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcategories | Increased knowledge about the disease and treatment | Enhanced sense of security | Increased self-knowledge |

| Support from other healthcare professionals | Easy access | Learnt how to take care of myself | |

| Experiencing participation |

3.1 Encountering competence

The interviews clearly revealed that participants had encountered competence, which was described in the subcategories: Increased knowledge about the disease and treatment; Support from other healthcare professionals; and Experiencing participation.

3.1.1 Increased knowledge about the disease and treatment

When you have an appointment with the rheumatologist, when you come out, all your questions are usually unanswered, because you don't remember … so it's the time … that they [nurse] have time to listen, which also means that the involvement is there… (I.1)

…both the nurse and the doctor are highly specialized, so I never think that the nurse I'm meeting will be lacking in competence—that has never occurred to me… I know that if the nurse felt uncertain, she would check with a doctor, she wouldn't just chance it. (I. 12)

…when I had had the opportunity to talk to her and pose all my questions… that is what has made me take the medications. (I. 6)

3.1.2 Support from other healthcare professionals

She has also been able to help with things like getting access to an occupational therapist… (I. 1)

She checked whether I needed to see a dietician. I actually needed a nutritional beverage… the follow-up here is comprehensive. (I. 11)

3.1.3 Experiencing participation

…for my own part, these frequent contacts with the nurse were extremely good. I suffered a drug injury in the middle of all this… I could discuss [this] with her the whole time, every 6 weeks. (I. 8)

…reached me on my own level, so to speak, and I'm quite young, I suppose … I've had it (RA) for 5 years… (I. 12)

3.2 A sustainable relationship

Participants felt that the frequent visits to the nurse created a sustainable relationship, as described in the subcategories Enhanced sense of security and Easy access.

3.2.1 Enhanced sense of security

Talking to a nurse is often a little easier than talking to a doctor, so I actually think that it becomes more like talking to a friend. (I. 4)

For me, this was perfect… It was absolutely super to have such support…actually… having her was a fantastic support…and so often…she phoned me at home and I phoned her…it was fantastic. (I. 8)

3.2.2 Easy access

You could talk without being interrupted and tell about what was perceived as difficult and what was good… having been listened to… I think that being listened to is immensely important, that someone has time to sit… (I. 2)

…then I could phone immediately and say that this doesn't work… she could talk to the doctor… it saved an enormous amount of time...and instead of having to wait for an appointment with the doctor, she fixed everything… (I. 11)

3.3 Making a personal journey

What made this “journey” possible was the targets set during the encounters with the nurse, which had a focus on, as far as possible, well-being, and the fact that the meetings took place at regular intervals. This enabled participants to gain greater insight into both themselves and their disease. Several participants revealed that they had not previously raised certain issues with their doctor, owing to a lack of time, or with other healthcare staff, but also that they themselves had not been aware that they lacked knowledge about their disease.

The subcategories that arose within this category were: Increased self-knowledge and Learnt how to take care of myself.

3.3.1 Increased self-knowledge

…I had a completely different view of it at that time…it's difficult to explain… I became more open and … this is how it is, I heard myself say… I have joint problems … almost kind of proud that I am still mobile…it has changed completely from a feeling of guilt at having rheumatoid arthritis … I'm a rheumatic but I am not my disease. (I. 2)

3.3.2 Learnt how to take care of myself

…I would say that I am not very active…she [nurse] sort of gave me a kick on the behind … and it's still a bit like that today … now she is sitting on my shoulder… I have to go for a walk now. (I. 7)

…the best thing of all, learning to put one's foot down—now, that's enough—irrespective of what it is. (I. 11)

People at the university haven't realized it. They are really surprised when I tell them that I'm ill, that I must go home and inject myself—everyone is very shocked, [saying] ‛What, are you ill?’ Because nobody notices, I feel so good and am active, it has been so wonderful to be rid of the sickness label. (I. 12)

I have learnt to think in a new way; it has led to…some sort of change in my personality…as I have had to reorganize a lot of things…and also stopped smoking in the middle of all this. (I.9)

4 DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to describe the experience of patients with RA attending person-centred, nurse-led clinics over a 12-month period.

Three categories emerged that described participants' encounters with the nurse.

4.1 Encountering competence

Participants reported feeling better when encountering a competent nurse who provided them with information about their disease, as well as tips and advice that they could use in everyday life, whereby they gained an increased understanding of the treatment. This is supported by a study conducted in the Netherlands, which found that patients requested education, self-management support, emotional support and well-organized care (van Eijk-Hustings et al., 2013). In the present study, participants stated that they found it easy to talk to the nurse. When they received information about their treatment, it increased the likelihood that they would take their medication, leading to better functioning in everyday life and reducing the negative effects of RA (Arvidsson et al., 2006).

Participants in the present study considered that being involved in their care was essential. In their experience, the nurse listened to them and the health plan that they developed with the nurse could be revised if necessary; this demonstrated that the nurses in the present study adopted a person-centred approach. This is similar to the findings of Bala et al. (2012), who highlighted the importance of encouraging patients to participate in improving their own care and well-being, as well as actually feeling involved and being allowed to decide about matters pertaining to their own care. A vital aspect is being seen as a human being and not just as a diagnosis (Ekman et al., 2011). Person-centred care assumes that healthcare professionals can work in a person-centred way, which is clearly described in the study by Alharbi, Carlstrom, Ekman, Jarneborn, and Olsson (2014). These authors state that some care staff find it easier than others to adopt new methods of working, and that not all such staff have the tools required to invite the patient to participate in her/his own care. They also revealed that not all patients want to be involved in their own care, which may be due partly to healthcare staff not knowing how to invite the patient to participate. Hospital managers also have a responsibility to provide healthcare staff with the tools and education necessary for working in a person-centred manner and viewing patients as partners, not merely as patients (Alharbi et al., 2014).

4.2 A sustainable relationship

The participants clearly described that the relationship they had formed with the nurse was sustainable and that they had experienced an increased sense of security during their participation in the study. This was expressed in terms of an emphasis on encountering the same nurse throughout the study and building a relationship with them, and the fact that the nurse was easily accessible. The importance of the nurse being easily accessible has also been demonstrated in other studies (Bala et al., 2012; Larsson et al., 2012). Accessibility was described as the nurse being easy to reach, either by telephone or by visiting the nurse-led clinic, and as enhancing participants' sense of security (Bala et al., 2012; Larsson et al., 2012).

The view of participants in the present study, that a sustainable relationship is positive, accords with the findings of a study from the UK comparing nurse-led and physician-led rheumatology care (Vinall-Collier, Madill, & Firth, 2016). The study revealed that the nurses put greater effort into “building a relationship” and engaging more in conversations with patients on a personal level compared with physicians. Their patients also had a positive view of the continuity of meeting with the same nurse at each visit (Vinall-Collier et al., 2016). The person-centred approach is based on building a relationship between the patient and healthcare staff (Ekman et al., 2011), which was the focus of the present study.

4.3 Making a personal journey

Participants in the present study expressed, in various ways, that they had gained new insights about themselves and their disease. Several of them stated that having had the disease for a long time did not mean that they had received or assimilated information about their disease and treatment to a sufficient extent, and this is supported by the findings of Arvidsson et al. (2006). Patients who learn about their treatment and situation have the opportunity to check how they are doing and are seen as individuals, enabling them to make wise choices in relation to their situation. Learning about their treatment may also help them to appraise their situation critically (Arvidsson et al., 2006). Without such learning, it may be difficult for them to know the treatment and support opportunities that are available. In the present study, the nurse helped participants to gain self-insight by strengthening and supporting them, listening to their stories and seeing the person behind the diagnosis, which participants considered was sometimes missing during other healthcare visits. Ekman et al. (2011) argued that the patient story is central to the care process, as the patient is an expert on her/his own disease and life situation.

Participants also reported gaining increased insight into life in general, apart from the disease, learning new things about themselves, learning to say “no” and daring to tell their colleagues that they suffered from RA. They considered that the nurse had also helped to support them in this respect, which could partly be explained by meeting the same nurse on each occasion, making it easier to continue their previous discussion as they did not have to start from scratch on every occasion. Bergsten et al. (2011) described that gaining increased insight about oneself and one's disease, as well as striving for a good life, is a state that varies over time. These authors also revealed that striving for a good life depends on one's personal resources and the level of support from others (Bergsten et al., 2011).

Participants had also learnt how to take care of themselves. They had been strengthened in relation to their situation, which could include continuing to exercise after completion of the study. Nurse-led clinics can help some patients to gain insight into their own potential, what they are capable of, as well as supporting them in their current situation (Vinall-Collier et al., 2016). In the present study, participants had moderate to high disease activity and that (moderate to high disease activity) could be used as a screening tool to identify which patients might benefit from more frequent visits with a nurse. Patients who have a moderate-to-high disease activity score at more than one visit and/or who ask a lot of questions about the disease and treatment could benefit from a more person-centred intervention in order to meet their needs.

The strength of the phenomenographic method includes capturing perceptions of a specific phenomenon. The fact that the interviewer was a nurse who encountered RA patients on a daily basis and thus has a certain preunderstanding and knowledge in this area could have constituted a strength as well as a weakness. There could have be a weakness in the fact that the interviewer had not removed her professional “hat”. In the research situation, reflection on one's own profession and experiences must take place continuously, in order to avoid influencing the results. Consequently, efforts were made to be open and sensitive in the interview situation, to minimize the influence of preunderstanding. The reliability of the results was strengthened by the description of the analytical process and the use of quotations. The analytical process comprised listening to the interviews, repeatedly re-reading the interview transcripts, identifying meaning units, and coding and sorting them into subcategories, and then dividing them into three categories. The meaning units were adjusted until the subcategories were identified, and resulted in three main categories being established. During this work, a great deal of reflection took place and the researchers often took a “step back”, in order to scrutinize what had emerged. All researchers in the team performed the analysis together.

The results can be transferred to other contexts, as several studies have reported similar findings. It is likely that they may also be applicable to individuals with other chronic diseases that affect their everyday life, but more research is required in order to ascertain whether this is the case.

5 CONCLUSION

The study revealed that patients with RA are not always knowledgeable about their situation but that encounters with a nurse at regular intervals strengthened them on several levels and gave them increased knowledge about their disease. They had the opportunity to pose questions that they had not dared, been able or remembered to ask previously. The person-centred approach employed in our study meant that the patients were encountered at their own level, in line with their knowledge and needs. For a good encounter between patient and healthcare staff to take place, openness and two-way communication are required. During the study period, participants underwent a process that can be thought of as comprising three steps. The first step was Encountering competence in their meetings with the nurse. Participants then climbed up a step when they encountered A sustainable relationship, and the third and final step described Making a personal journey.

It would be interesting to explore how healthcare professionals experience working in accordance with a person-centred approach. Further studies are required to gain more knowledge about where improvements need to be made in the care of patients patients whose well-being is compromised by living with RA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Funding obtained from the Centre of Person-Centered Care at University of Gothenburg, Sweden, Swedish Rheumatism association.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.