Electronic Patient Portals as a Modality for Returning Reclassified Genetic Test Results

Funding: Supported by a National Cancer Institute research grant (NIH/NCI R00CA256216), the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCI 3P30 CA 142543-10S3), and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR003163).

ABSTRACT

Background

Most reclassified genetic test results are clinically inactionable and burdensome for healthcare providers to return to patients. The feasibility of using electronic patient portals (e.g., MyChart) to return reclassified results remains unclear.

Methods

Patient and provider initiated MyChart actions were obtained from MyChart data and matched to patient demographic and clinical information using unique patient medical record numbers. Data on who (patient or provider) sent and read these messages and when (date and time) were collected for clinically actionable and inactionable reclassifications.

Results

Among 801 patients with 828 reclassified variants in cancer susceptibility genes, 551 had an active MyChart account at the time of reclassification. Patients with active MyChart accounts were less likely to be Hispanic (p < 0.001) compared to other ethnic groups. Of these, 302 (55%) were notified about 308 reclassified results (307 inactionable and 1 actionable) via MyChart messages, and 80% (244/302) read the message within a median time of 3.6 h.

Conclusion

We find that it is feasible to return reclassified results via electronic patient portals for most patients, but alternative modalities are still necessary. Unidirectional, low-touch modalities of recontact can be used to efficiently return the increasing number of inactionable reclassified results.

1 Introduction

Of the 6%–15% of germline variants that undergo reclassification over a 5–10-year period, only ~10% are clinically actionable (Mersch et al. 2018; Turner et al. 2019; Davidson et al. 2022). Clinical actionability in this context refers to a change in care/management recommended in response to updated genetic test results. While recontact after reclassification and clinical follow-up is clearly beneficial for patients who receive these 10%, whether and how to recontact the remaining 90% with clinically inactionable reclassifications remains unclear. Patients want to know about amended results, and providers likely have an ethical duty to return them (Appelbaum et al. 2023). As the frequency of reclassification increases, a primary challenge today is efficiently relaying this large volume of results to patients. Recontact is burdensome for the healthcare system, and it is necessary to identify optimal strategies to return reclassified results, especially inactionable results that comprise the vast majority. A persistent question in the field is: will unidirectional, low-touch modalities of recontact (e.g., electronic patient portal message) suffice?

Providers endorse patient portals as a modality that can efficiently return inactionable results, e.g., variant of uncertain significance (VUS) downgraded to benign or likely benign (B/LB) (Makhnoon et al. 2023). For clinically actionable results such as VUS to/from pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP), telephone or in-person conversations are still preferred. Evidence suggests that recontact procedures and clinical follow-up after reclassification remain highly variable. Patients want to receive reclassified results, and the psychosocial impact of recontact is largely positive (or neutral), although somewhat dependent on the information's clinical impact (Halverson et al. 2020; Margolin et al. 2021). Importantly, patients have a right to know their own results and to receive them in a manner that does not cause undue harm. It is unclear if returning inactionable reclassified results through electronic patient portals is feasible for the healthcare system and what impact the modality may have on proximal patient outcomes (reading the message and timeliness of reading the message).

In this study, we attempted to understand the feasibility of using electronic patient portals (e.g., MyChart) in returning reclassified results to patients with the goal of informing strategies that can be used to return reclassified results efficiently.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethical Compliance

The study was approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center's Institutional Review Board.

This is a retrospective analysis of electronic medical record data from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW). The main outcome is the feasibility of using patient portals, defined as the actual fit for utility, suitability for everyday use, or practicability (Proctor et al. 2011).

2.2 Setting

At UTSW, all germline tests are performed by outside laboratories and results are disclosed after review from a genetic counselor, i.e., delayed release under Cures Act (Arvisais-Anhalt et al. 2023). As of 2021, initial test results and actionable reclassified results are returned via telephone with certified mail and MyChart as backup. Inactionable reclassifications are returned either via MyChart or mail without the use of telephone calls. MyChart messages include a patient-friendly letter accompanying the amended result report and contact information for follow-up questions, following best practices on delivering genetic information via patient portals (Korngiebel and West 2022). The MyChart messages are sent by genetic counseling assistants and thus are set to not receive responses via MyChart from patients directly.

2.3 Data Sources

We identified patients using MyChart by extracting data based on cancer genetics department-type appointments with an encounter between January 1, 2007 (when MyChart was first available throughout UTSW) and December 31, 2023. Eligible patients with reclassifications were identified using a departmental database that contains all patients with reclassified results. Reclassifications were categorized as clinically actionable or inactionable through chart review. We queried three different MyChart data tables for patient data, access patterns, and message actions: Patient_MYC (16 fields), MYC_Patient_USER_ACCSS (eight fields), MYC_MESG (36 fields). Epic demographic data was matched to MyChart data using unique patient medical record numbers.

Patient initiated MyChart actions were categorized as: appointments, billing/financial, labs/imaging (viewing test results), medical advice (communication to medical providers), medical history, messaging (viewing/responding to communication from medical providers or generated automatically), and MyChart account maintenance. Provider-initiated MyChart messages used to return results were identified using relevant keywords on message subject lines (e.g., amended, updated, and genetic) and manually reviewed to ensure accuracy. Data on who (patient or provider) sent, received, and read messages and when (date and time) were collected.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

We describe characteristics using means ± standard deviations (SD), or medians with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Comparison of categorical variables was performed by Chi-squared test or Z-test; continuous variables were compared using t-test or its non-parametric counterpart, Wilcoxon rank sum test. All statistical analysis was performed in R at a significance level of 0.05.

3 Results

In total, 801 patients with 828 reclassified variants in cancer susceptibility genes were included in the analysis; 28 patients had two reclassifications each. The reclassifications represent variants originally classified as VUS (89%), P/LP (10%), and B/LB (1%) that were reclassified to B/LB (84%) and P/LP (15%). Of all reclassifications, 52 (7%) were clinically actionable. Median time to reclassification was 3.1 years for actionable results and 2.3 years for inactionable results.

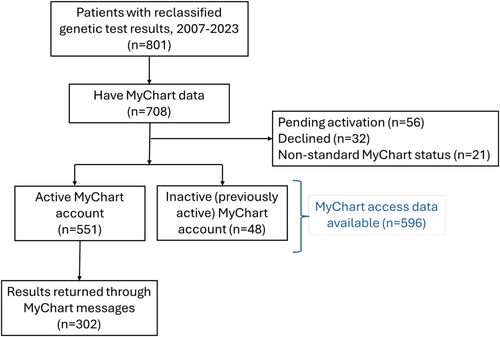

Overall, 708 (88%) patients had MyChart data, of whom 551 (78%) had active MyChart accounts (defined as one or more log-ins) while the rest had inactive accounts (n = 48, 7%), were pending activation (n = 56, 8%), had declined activation (n = 32, 5%) or had other status (n = 21, 2%) (Figure 1). Therefore, 250 (31%) patients did not have an active MyChart account at the time their variant was reclassified. Patients with active MyChart accounts were less likely to be Hispanic (p < 0.001) but were similar with regard to age and sex (Table 1). Between 2021 and 2023, the proportion of patients with active MyChart accounts increased from 68% to 84%.

| Characteristic | Categories | Active MyChart users n = 551 (%) | All others n = 250 (%) | p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of Genetic test, years, mean ± SD | 53.3 ± 14.5 | 53.3 ± 15.9 | 0.83 | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 437 (79) | 197 (79) | 0.95 |

| Male | 114 (21) | 52 (21) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | Hispanic | 45 (8) | 37 (15) | < 0.0001 |

| Not Hispanic | 435 (79) | 138 (55) | ||

| Unknown | 71 (13) | 74 (30) | ||

| Race, n (%) | White | 309 (56) | 121 (47) | < 0.0001 |

| Black/African American | 93 (17) | 33 (13) | ||

| Asian | 56 (10) | 7 (3) | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Unknown/other | 89 (16) | 85 (34) | ||

- * Comparisons of categorical variables were performed by Chi-squared test, or continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test.

In addition to known MyChart status, 596 (84%) patients also had data on MyChart use. The total number of MyChart logins was 407,481, with 684 ± 1002 logins per patient (median logins: 361, IQR: 77–919). The total number of MyChart actions (excluding log-in and log-out) is 5,218,021 (median MyChart actions per patient: 4669; IQR: 1031–11,794). Of the patients with active MyChart accounts, most (85%) were frequent users (number of MyChart use ≥the median value of 361 log-ins). Three main actions accounted for 80% of all MyChart use: scheduling appointments (38%), updating medical history (26%) and viewing, sending, or responding to clinic messages (16%).

In total, 302 (55%) patients with active accounts were notified about 308 reclassified results (307 inactionable and 1 actionable) via MyChart messages. The remaining 45% received results that were either reclassified before 2021 or were clinically actionable. Most patients (80%, 244/302) read the message within a median of 3.6 h (IQR: 14 min to 6 days). Return of results through MyChart did not alter patients' portal use behavior with regard to the number of messages sent from patient to provider (total or to seek medical advice) during the month before (mean 8.6, SD = 8.9) compared to the month after reclassification (mean 8.8, SD = 13.4).

4 Discussion

We explore the feasibility of returning reclassified genetic test results through electronic patient portal messages, a unidirectional, low-touch modality of recontact that has long been discussed as a way for healthcare systems to manage the increasing number of reclassified results (Mighton et al. 2021). We find that it is feasible to return reclassified results via electronic patient portals: over 70% of patients had active MyChart accounts at the time of reclassification and most read messages within a few hours. Although these data indicate that the return modality is suitable for everyday use and aids clinical efficiency, patient acceptability (the extent to which the modality is agreeable, palatable, and satisfactory to patients (Proctor et al. 2011)) remains to be explored. Alternative modalities such as mail and telephone calls are still necessary for patients who do not or cannot use patient portals. Clinical efficiency resulting from the use of digital technologies in genetic counseling is ethically desirable (van Lingen et al. 2025), especially when resources are scarce, as is the case with genetic counselors.

Standardized patient portal messages have several advantages. It decreases time investment by the genetic counselor, allowing them to allocate time where input is most necessary, e.g., counseling for change in care based on clinically actionable reclassified results. Nationally, three out of five US adults have an electronic patient portal (Strawley and Richwine 2023; Giardina et al. 2018; Wedd et al. 2023), mostly at a primary care provider's office rather than at a specialist's office, where genetic tests are commonly ordered and amended results returned. Since reclassification can take years (Thummala et al. 2024), primary care provider's involvement in the return process may be necessary when patients are no longer under the care of the ordering provider. Although genetic test reports are not usually available as structured lab results, a common portal use action among MyChart users is viewing results (Gerber et al. 2014). By leveraging this portal use behavior, it may be possible to return amended results in other clinical settings and maintain consistency of information provision. Future research should examine returning results via patient portals when patients transition care to different medical systems, the interoperability of patient portals between systems, and who has the duty to return results in these circumstances. The investment required to develop, maintain, and secure patient portals is substantial and must be weighed against the anticipated clinical efficiency.

The impact of using electronic patient portals to return reclassified results on equitable genomic care delivery remains unclear. Existing evidence suggests that patient portal activation rates and rates of viewing results are consistently lower among Black and Hispanic patients (Richwine et al. 2023) which is mirrored in the lower MyChart activation rate among non-White patients observed in our data. Lower health literacy is also associated with lower patient portal awareness, activation, and use (Deshpande et al. 2023) suggesting a selection bias in the type of patient who has benefited from this return modality. Combined with the known inequalities in accessing genetic tests (Saulsberry and Terry 2013), higher VUS rates in racial/ethnic minorities (Caswell-Jin et al. 2018) and VUS resolution being a primary motivation of variant interpretation, patients who are most likely to receive reclassified results may be least likely to be active patient portal users. Although the patient portal adoption rate has increased over time, it is critical to ensure that policies on returning reclassified results serve all patients equally and do not disenfranchise digitally illiterate patients or those who do not have the resources to utilize patient portals. Multilevel solutions may be necessary to increase equitable adoption of electronic patient portals, especially among Hispanics, as the known barriers span personal-level (general preference for face-to-face care, limited health literacy) to institutional-level (patient portals not available in Spanish).

Limitations of the study include the practice setting—feasibility data are specific to implementation settings and results from an academic medical center may not be generalizable to healthcare settings with different patient portal adoption rates. Another limitation is the lack of data on follow-up telephone inquiries from patients. Patients may have called providers directly to ask clarifying questions about their amended test results. This data were not available for analysis but, anecdotally, few such telephone calls are received in response to inactionable reclassifications at the clinic.

In summary, patient portals are a feasible modality for returning clinically inactionable reclassified genetic test results in healthcare settings with high MyChart adoption rates. Indeed, most patients in this study viewed their results within an average of 3.6 h, suggesting that MyCharts can be leveraged to deliver results to patients in a timely manner. However, alternative modalities are still necessary for patients who do not have active MyChart accounts, and patient acceptability outcomes are needed before wider implementation. The modality may positively impact the efficiency of genomic care delivery.

Author Contributions

S.M. conceived the idea and drafted the manuscript; M.L., M.B., C.K., S.W.M., C.M. were involved in data acquisition and analysis; A.B. and J.M. helped refine the analytic model. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Ethics Statement

Approved by IRB under waiver of informed consent.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.