Outcome of Acetaminophen-Induced Acute Liver Failure Managed Without Intracranial Pressure Monitoring or Transplantation

Abstract

Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure (ALF) may require emergency liver transplantation (LT) in the presence of specific criteria, and its management may also include intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring in selected patients at high risk of cerebral edema. We aimed to test the hypothesis that management of such patients without ICP monitoring or LT would yield outcomes similar to those reported with conventional management. We interrogated a database of all patients treated in an intensive care unit for acetaminophen-induced ALF between November 2010 and October 2016 and obtained relevant information from electronic medical records. We studied 64 patients (58 females) with a median age of 38 years. Such patients had a high prevalence of depression, substance abuse, or other psychiatric disorders and had ingested a median acetaminophen dose of 25 g. No patient received ICP monitoring or LT. Overall, 51 (79.7%) patients survived. Of the 42 patients who met King’s College Hospital (KCH) criteria, 29 (69.0%) survived without transplantation. There were 45 patients who developed severe hepatic encephalopathy, and 32 (71.1%) of these survived. Finally, compared with the KCH criteria, the current UK Registration Criteria for Super-Urgent Liver Transplantation (UKRC) for super-urgent LT had better sensitivity (92.3%) and specificity (80.4%) for hospital mortality. In conclusion, in a center applying a no ICP monitoring and no LT approach to the management of acetaminophen-induced ALF, during a 6-year period, overall survival was 79.7%, and for patients fulfilling KCH criteria, it was 69.0%, which were both higher than for equivalent patients treated with conventional management as reported in the literature. Finally, the current UKRC may be a better predictor of hospital mortality in this patient population.

Abbreviations

-

- 4-H

-

- quadruple-H

-

- ALF

-

- acute liver failure

-

- ALP

-

- alkaline phosphatase

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- ANZROD

-

- Australian and New Zealand Risk of Death

-

- APACHE

-

- Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

-

- CCT

-

- cranial computed tomography

-

- CVC

-

- central venous catheter

-

- GGT

-

- gamma-glutamyltransferase

-

- ICH

-

- intracranial hemorrhage

-

- ICP

-

- intracranial pressure

-

- ICU

-

- intensive care unit

-

- INR

-

- international normalized ratio

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- KCH

-

- King’s College Hospital

-

- KDIGO

-

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- NAC

-

- N-acetylcysteine

-

- PaCO2

-

- partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

-

- PCC

-

- prothrombin complex concentrate

-

- SOFA

-

- Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

-

- UKRC

-

- UK Registration Criteria for Super-Urgent Liver Transplantation

-

- WCC

-

- white cell count

Acetaminophen overdose is among the leading causes of acute liver injury in the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, accounting for up to 74% of patients in some studies.1-4 The majority of these patients are young.5 Although most patients recover with the early administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and do not require intensive care unit (ICU) admission, some develop massive hepatic necrosis causing acute liver failure (ALF) characterized by jaundice, deranged clotting parameters, and hepatic encephalopathy with the potential to develop cerebral edema. These patients are typically admitted to the ICU and, in some centers, may receive intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring and emergency liver transplantation (LT) in the presence of specific criteria.6, 7 However, improvements in survival with medical therapy8 suggest that the use of ICP monitoring may not be necessary and that some patients undergoing LT based on published criteria might now survive with medical management alone.9

Identification of patients at the highest risk of death underpins the current guidelines for LT, with the King’s College Hospital (KCH) criteria being the most popular criteria for this purpose.10 However, the performance of such prognostic criteria is limited due to an imbalance between sensitivity and specificity.11 Subsequent modifications, like the current UK Registration Criteria for Super-Urgent Liver Transplantation (UKRC),12 have tried to address these imbalances, but the ideal prognostic model has not been established.

Moreover, the use of ICP monitoring in ALF is controversial and should only be considered in a highly selected subgroup of patients13 because this practice is challenging in patients with clotting abnormalities and may not improve survival.14

At our institution, we have a restrictive policy with regard to ICP monitoring and LT for patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF. This is because of the potential for spontaneous recovery,15 the high prevalence of psychiatric conditions,16 and the unclear benefit of invasive ICP monitoring in this unique patient population.17 However, to date, few studies have reported detailed analyses of patient-centered outcomes with standardized medical management of acetaminophen-induced ALF in the absence of any surgical component to its management.

We hypothesized that the previously mentioned highly restrictive approach to ICP monitoring and LT would yield outcomes similar to those reported with conventional management. To test this hypothesis, we studied all patients treated for acetaminophen-induced ALF and admitted to the ICU of our liver disease and transplantation referral center.

Patients and Methods

Study Design And Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of adult patients admitted to our ICU with acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury between November 2010 and October 2016. The study was approved by Austin Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics approval number LNR/17/Austin/460). The need for informed consent was waived.

Data Collection

We reviewed the patients’ medical records and obtained data from the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Adult Patient Database,18 extracting demographic data such as age, sex, comorbidities, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and III score, Australian and New Zealand Risk of Death (ANZROD),19 referral site, time of ingestion, acetaminophen dose, staggered ingestion, serum acetaminophen concentration, and contraindications to LT. Data regarding treatment and monitoring and hemodynamic and laboratory data were collected daily for the first 7 days after admission to the ICU of our LT referral center. Outcome data included ICU and hospital mortality, cause of death, LT, blood transfusions, and complications such as major bleeding (was defined as bleeding requiring angiographic, endoscopic, or surgical intervention or transfusion of blood products), sepsis (defined as proven or suspected infection with signs of organ dysfunction), cerebral edema, bowel ischemia, and cerebrovascular events.

Medical Management Of ALF

According to our institutional protocol, intravenous NAC was administered to all patients until discharge from the ICU. Medical management of ALF comprised a protocol-informed combination of 4 different treatment modalities referred to as the quadruple-H (4-H) approach:20 mild hyperventilation, high-dose hemodiafiltration, hypothermia, and hypernatremia. Patients with Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 and/or respiratory acidosis in the setting of severe encephalopathy (defined as encephalopathy grade ≥ 3) were intubated and mechanically ventilated to achieve a partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) between 32 and 35 mm Hg. Noradrenaline infusion via a central venous catheter (CVC) was titrated to maintain a mean arterial pressure >60 mm Hg as continuously measured via an arterial catheter. The adjunctive use of intravenous hydrocortisone, vasopressin, and the use of additional hemodynamic monitoring was at the discretion of the treating physician. In patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy (including all those who were intubated), oliguria, acidosis, or hyperammonemia (>80 µmol/L), we used high-dose hemodiafiltration (40-60 mL/kg/hour) with anticoagulant-free circuits or prostacyclin anticoagulation. Mild hypothermia (target temperature of 35°C) was achieved by circulating the extra-corporeal circuit at room temperature or with external cooling. We targeted for a serum sodium concentration of 148-152 mmol/L, using a continuous infusion of hypertonic saline (20% NaCl via CVC) as required. The presence or absence of cerebral edema was assessed by daily neurological examination for signs of intracranial hypertension with additional cranial computed tomography (CCT) when clinically indicated. Notably, our institutional protocol suggests a transfusion of fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, or platelets for patients with severe coagulopathy (defined as international normalized ratio [INR] >5, fibrinogen <0.8 g/L, and platelets <20 ×109/L).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software, version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical variables as frequencies with percentages. Patients were stratified retrospectively using the modified KCH criteria for LT10, 21: arterial pH <7.3 after volume resuscitation, blood lactate level >3.0 mmol/L at 12 hours after admission, or the combined findings of encephalopathy grade 3 or higher, creatinine >300 μmol/L (or hemodiafiltration within 24 hours of admission), and INR of >6.5. Patients were also stratified using the current UKRC for super-urgent LT12: pH <7.25 more than 24 hours after overdose and after fluid resuscitation, blood lactate >5 mmol/L on admission and >4 mmol/L 24 hours later in the presence of hepatic encephalopathy, or the combined findings of encephalopathy grade 3 or higher, creatinine >300 μmol/L, and INR of >6.5. Continuous data were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 64 patients treated in the ICU between November 2010 and October 2016. The majority of patients were females (90.6%), their median (IQR) age was 38 (32-47) years, and the majority had a history of depression, alcohol or illicit drug abuse, or other psychiatric disorders (Table 1). There were 42 (65.6%) patients who satisfied KCH criteria (the KCH group).

| Patient Characteristics | Non-KCH Group (n = 22) | KCH Group (n = 42) | Total (n = 64) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 39 (33-47) | 38 (31-45) | 38 (32-47) | 0.62 |

| Sex, female | 19 (86.4) | 39 (92.9) | 58 (90.6) | 0.41 |

| APACHE II score | 13 (8-18) | 20 (13-25) | 18 (10-23) | 0.001 |

| APACHE III score | 53 (37-76) | 78 (61-105) | 73 (53-92) | <0.001 |

| ANZROD | 0.21 (0.09-0.37) | 0.44 (0.19-0.70) | 0.31 (0.13-0.52) | 0.003 |

| SOFA score | 8 (4-9) | 11 (8-14) | 10 (6-13) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Depression | 12 (54.65) | 29 (69.1) | 41 (64.1) | 0.25 |

| Substance abuse | 5 (22.7) | 11 (26.2) | 16 (25.0) | >0.99 |

| Alcohol abuse | 8 (36.4) | 12 (28.6) | 20 (31.3) | 0.52 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 7 (31.8) | 13 (31.0) | 20 (31.3) | 0.94 |

| Overdose characteristics | ||||

| Accidental overdose | 13 (59.1) | 21 (50.0) | 34 (53.1) | 0.49 |

| Staggered ingestion | 10 (45.4) | 16 (43.2) | 26 (44.1) | 0.87 |

| Delay to ICU admission, days | 3.9 (2.1-8.0) | 2.4 (1.8-3.7) | 2.6 (1.8-4.7) | 0.06 |

| Ingested acetaminophen dose, g | 24 (12-50) | 25 (15-40) | 25 (15-43) | 0.81 |

| Highest acetaminophen level, µmol/L | 30 (30-264) | 226 (83-749) | 180 (30-532) | 0.02 |

| Physiology at ICU admission | ||||

| pH | 7.4 (7.4-7.5) | 7.3 (7.2-7.4) | 7.4 (7.3-7.4) | <0.001 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 2.4 (1.8-3.3) | 7.1 (4.3-10.0) | 4.5 (2.5-7.8) | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | 5388 (2848-8420) | 5890 (2552-8413) | 5877 (2552-8420) | 0.93 |

| GGT, U/L | 182 (85-288) | 134 (60-289) | 155 (73-288) | 0.36 |

| ALP, U/L | 111 (79-161) | 123 (101-156) | 116 (90-157) | 0.50 |

| Bilirubin, µmol/L | 70 (39-107) | 70 (53-96) | 70 (53-99) | 0.99 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 134 (55-248) | 144 (90-229) | 143 (83-246) | 0.65 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 7.3 (3.8-13.0) | 6.2 (3.5-9.7) | 6.3 (3.5-9.9) | 0.34 |

| INR | 3.3 (2.1-4.4) | 4.4 (3.3-5.8) | 4.1 (2.6-5.6) | 0.01 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 1.8 (1.4-2.5) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 1.4 (1.2-2.4) | 0.07 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 115 (107-131) | 111 (96-131) | 114 (101-131) | 0.38 |

| WCC, ×109/L | 9.9 (5.1-14.0) | 13.0 (6.8-19.0) | 11.0 (6.1-17.0) | 0.04 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 152 (113-183) | 149 (106-224) | 149 (106-208) | 0.85 |

| Ammonia level, µmol/L | 80 (60-104) | 142 (92-176) | 112 (74-159) | <0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy at ICU admission | 0.01 | |||

| Grade 0 | 12 (54.6) | 5 (11.9) | 17 (26.6) | |

| Grade 1 | 2 (9.1) | 4 (9.5) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 2 (9.1) | 6 (14.3) | 8 (12.5) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (4.6) | 4 (9.5) | 5 (7.8) | |

| Grade 4 | 5 (22.7) | 23 (54.8) | 28 (43.8) |

NOTE:

- Data are given as median (IQR) or n (%).

In the KCH group, 22 patients had severe acidosis, 34 had a lactate level >3 mmol/L at 12 hours after admission to our ICU, and 12 patients fulfilled the combined criteria of coagulopathy, encephalopathy, and acute renal failure. The cumulative ingested dose of acetaminophen was 25 (14-43) g, and the ingestion was staggered in 26 (44.1%) patients. More than 50% of all cases were accidental overdoses. Peak acetaminophen levels were significantly higher in the KCH group, as were illness severity scores (APACHE, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA], and ANZROD) and blood levels of lactate, ammonia, INR, and white cell counts (WCCs).

Contraindications to LT were present in 23 (35.9%) patients. Such contraindications included major psychiatric disorder or multiple suicide attempts in 10 (15.6%) patients, ongoing alcohol or drug abuse in 6 (9.4%) patients, medical reasons in 3 (4.7%) patients, and multiple or unspecified reasons in 4 (6.3%) patients.

Interventions

In this study population, no patient received invasive ICP monitoring or LT. All patients received intravenous NAC, and the majority were treated with prophylactic antibiotics (90.6%), hemo(dia)filtration (75.0%), and hypertonic saline (71.9%). The proportion of patients requiring mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and transfusion of blood products was higher in the KCH group compared with the non-KCH group (Table 2). In patients requiring mechanical ventilation, the mean PaCO2 over the first 10 days in the ICU was 35 ± 4.9 mm Hg in the KCH group and 36 ± 4.3 mm Hg in the non-KCH group. Invasive cardiac output monitoring was used in 12 (18.8%) patients, and jugular venous oxygen saturation was measured in 4 (6.2%) patients.

| Non-KCH Group (n = 22) | KCH Group (n = 42) | Total (n = 64) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||||

| Noradrenaline | 6 (27.3) | 31 (73.8) | 37 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| NaCl 20% | 9 (40.9) | 37 (88.1) | 46 (71.9) | <0.001 |

| Hemodiafiltration | 10 (45.5) | 38 (90.5) | 48 (75.0) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 8 (36.4) | 35 (83.3) | 43 (67.2) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotics | 17 (77.3) | 41 (97.6) | 58 (90.6) | 0.02 |

| Cardiac output monitoring | 3 (13.6) | 9 (21.4) | 12 (18.8) | 0.52 |

| Jugular venous oximetry | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (6.2) | 0.29 |

| Transfusions | ||||

| Red blood cells | 8 (36.4) | 35 (83.3) | 43 (67.2) | <0.001 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 4 (18.2) | 32 (76.2) | 36 (56.2) | <0.001 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 2 (9.1) | 26 (61.9) | 28 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| PCC | 0 (0.0) | 7 (16.7) | 7 (10.9) | 0.09 |

| Platelets | 2 (9.1) | 25 (59.5) | 27 (42.2) | <0.001 |

NOTE:

- Data are given as n (%).

Outcomes

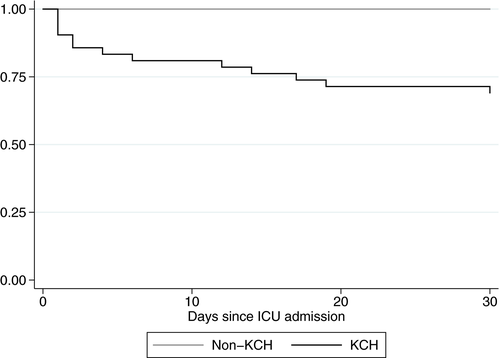

Of 64 patients treated for acetaminophen-induced ALF, 51 (79.7%) patients survived and 13 (20.3%) patients died. The majority of deaths occurred within the first 2 weeks of ICU admission (Fig. 1). In the KCH group, 29/42 (69.1%) survived with medical management. In predicting hospital mortality, the KCH criteria had a sensitivity (95% confidence interval) of 100.0% (75.3%-100.0%) and specificity of 43.1% (29.3%-57.8%). In total, 45 (70.3%) patients developed severe hepatic encephalopathy (≥grade 3), 32 (71.1%) of whom survived.

Overall, the most common complications were sepsis (37.5%) and major bleeding (26.6%). The most common sources of sepsis were bloodstream (33.3%), abdominal (29.2%), and pulmonary (20.8%) infections. Blood cultures were positive for bacteria in 11 (45.8%) patients and for Candida species in 3 (12.5%) patients. Major bleeding occurred from the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract (29.4% each), from vascular access sites (11.8%), or from pulmonary (5.9%) or multiple (23.5%) sources. The most common therapeutic interventions were transfusion of blood products (all bleeding patients), endoscopy (29.4%), surgery (11.8%), and angiographic embolization (5.9%). Bowel ischemia occurred in 3 (4.7%) patients and was associated with sepsis in each case (Table 3). Compared with survivors, nonsurvivors had significantly higher illness severity scores, degrees of encephalopathy, lactate levels, and WCCs and were more likely to require noradrenaline at ICU admission (Table 4).

| Outcomes | Non-KCH Group (n = 22) | KCH Group (n = 42) | Total (n = 64) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 0.003 | |||

| Died | 0 (0.0) | 13 (31.0) | 13 (20.3) | |

| Survived | 22 (100.0) | 29 (69.0) | 51 (79.7) | |

| Length of stay | ||||

| ICU | 3 (1.8-6.0) | 9.8 (4.5-17.0) | 6.3 (2.3-13.0) | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 9.0 (5.0-13.0) | 16.0 (6.0-27.0) | 12.0 (5.5-19.0) | 0.03 |

| Complications | ||||

| Sepsis | 1 (4.6) | 23 (54.8) | 24 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| Bowel ischemia | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (4.7) | 0.54 |

| Stroke | 1 (4.6) | 2 (4.7) | 3 (4.7) | >0.99 |

| Major bleeding | 1 (4.6) | 16 (38.1) | 17 (26.6) | 0.003 |

NOTE:

- Values are presented as median (IQR) or n (%). Major bleeding was defined as bleeding requiring angiographic, endoscopic, or surgical intervention.

| Nonsurvivors (n = 13) | Survivors (n = 51) | Total (n = 64) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 35 (33-43) | 38 (31-47) | 38 (32-47) | 0.90 |

| Sex, female | 11 (84.6) | 47 (92.2) | 58 (90.6) | 0.59 |

| APACHE III score | 125 (92-138) | 64 (45-81) | 73 (53-92) | <0.001 |

| ANZROD | 0.77 (0.54-0.87) | 0.25 (0.11-0.45) | 0.31 (0.13-0.52) | <0.001 |

| SOFA score | 15 (12-17) | 9 (5-10) | 10 (6-13) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 13 (100.0) | 30 (58.8) | 43 (67.2) | 0.01 |

| Vasopressor need | 10 (76.9) | 11 (21.6) | 21 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| KCH criteria fulfilled | 13 (100.0) | 29 (56.9) | 42 (65.6) | 0.003 |

| Contraindications to emergency LT, n = 52 | 11 (91.7) | 12 (26.7) | 23 (40.4) | <0.001 |

| Overdose characteristics | ||||

| Accidental overdose | 4 (30.8) | 30 (58.8) | 34 (53.1) | 0.12 |

| Staggered ingestion | 1 (10.0) | 25 (51.0) | 26 (44.1) | 0.03 |

| Ingested acetaminophen dose, g | 37 (15-43) | 24 (15-42) | 25 (15-43) | 0.66 |

| Peak acetaminophen level, µmol/L | 544 (162-809) | 134 (30-322) | 180 (30-532) | 0.02 |

| Physiology | ||||

| pH at admission | 7.16 (7.05-7.27) | 7.39 (7.30-7.46) | 7.37 (7.26-7.44) | <0.001 |

| Lowest pH | 7.08 (6.97-7.27) | 7.36 (7.30-7.41) | 7.34 (7.26-7.40) | <0.001 |

| Lactate at admission, mmol/L | 12.4 (8.6-20.0) | 3.5 (2.2-6.3) | 4.5 (2.5-7.6) | <0.001 |

| Peak lactate, mmol/L | 20.0 (10.6-22.0) | 4.2 (2.7-7.6) | 5.0 (3.0-8.6) | <0.001 |

| INR at admission | 4.8 (3.6-6.9) | 4.1 (2.5-4.6) | 4.1 (2.6-5.6) | 0.11 |

| Peak INR | 5.8 (4.6-7.7) | 4.4 (2.5-6.4) | 4.5 (3.2-6.5) | 0.05 |

| WCC at admission, ×109/L | 19.4 (10.7-27.7) | 10.0 (5.8-15.7) | 10.7 (6.1-17.4) | 0.01 |

| Peak WCC, ×109/L | 20.7 (13.4-27.7) | 13.5 (10.0-19.6) | 14.9 (10.3-21.7) | 0.03 |

| Ammonia level at admission, µmol/L | 155 (96-176) | 111 (73-148) | 112 (74-159) | 0.11 |

| Peak ammonia, µmol/L | 165 (118-176) | 123 (89-182) | 130 (94-180) | 0.16 |

| Peak ALT, U/L | 7652 (6268-10548) | 5877 (2848-9162) | 6646 (3017-9299) | 0.15 |

| Peak bilirubin, µmol/L | 163 (123-346) | 144 (73-245) | 151 (77-248) | 0.28 |

| Peak creatinine, µmol/L | 210 (169-317) | 148 (97-264) | 167 (102-280) | 0.06 |

| Peak urea, mmol/L | 9.6 (4.2-11.0) | 9.4 (4.5-14.6) | 9.5 (4.4-12.5) | 0.49 |

| Encephalopathy grade | 0.004 | |||

| Grade 0 | 0 (0.0) | 15 (31.2) | 15 (25.0) | |

| Grade 1 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.5) | 6 (10.0) | |

| Grade 2 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (16.7) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Grade 3 | 2 (16.7) | 3 (6.2) | 5 (8.3) | |

| Grade 4 | 10 (83.3) | 16 (33.3) | 26 (43.3) | |

| KDIGO | 0.02 | |||

| Stage 0 | 3 (23.1) | 33 (64.7) | 36 (56.2) | |

| Stage 1 | 2 (15.4) | 5 (9.8) | 7 (10.9) | |

| Stage 2 | 4 (30.8) | 6 (11.8) | 10 (15.6) | |

| Stage 3 | 4 (30.8) | 7 (13.7) | 11 (17.2) | |

| Complications | ||||

| Sepsis | 9 (69.2) | 15 (29.4) | 24 (37.5) | 0.01 |

| Bowel ischemia | 1 (7.7) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (4.7) | 0.50 |

| Stroke/ICH | 2 (15.4) | 1 (2.0) | 3 (4.7) | 0.10 |

| Major bleeding | 5 (38.5) | 12 (23.5) | 17 (26.6) | 0.31 |

NOTE:

- Data are given as median (IQR) or n (%).

Of the 13 patients who died, 11 (84.6%) had documented relative contraindications to LT, the majority being refractory psychiatric disorders or severe multiorgan failure. Causes of death included overwhelming sepsis (8 patients, 61.5%), multiorgan failure without proven sepsis (3 patients, 23.1%), and ischemic bowel and major ischemic stroke (1 case each). Clinical findings and available CCT images suggest that no patient died of cerebral edema–induced tonsillar herniation. The 2 patients who died despite not having contraindications to LT (both in the KCH group) deteriorated rapidly within 48 hours of ICU admission and died of refractory shock.

UK Regristration Criteria For Super-Urgent Liver Transplantation

There are 22 (34.4%) patients who fulfilled the UKRC, and 12 of them (54.5%) died (Table 5). Sensitivity for hospital mortality using UKRC criteria was 92.3% (95% confidence interval, 64.0%-99.8%), and specificity was 80.4% (95% confidence interval, 66.9%-90.2%). Notably, in the UKRC-negative group, 20 patients fulfilled KCH criteria, but only 1 of them died.

| UKRC Negative (n = 42) | UKRC Positive (n = 22) | Total (n = 64) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 41 (33-48) | 34 (21-41) | 38 (32-47) | 0.03 |

| Sex | 0.41 | |||

| Male | 3 (7.1) | 3 (13.6) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Female | 39 (92.9) | 19 (86.4) | 58 (90.6) | |

| Accidental overdose | 27 (64.3) | 7 (31.8) | 34 (53.1) | 0.01 |

| Staggered ingestion | 22 (56.4) | 4 (20.0) | 26 (44.1) | 0.01 |

| Cumulative acetaminophen dose, g | 25 (15-42) | 25 (15-43) | 25 (15-43) | 0.98 |

| APACHE III score | 63 (43-81) | 91 (64-125) | 73 (53-92) | <0.001 |

| ANZROD | 0.25 (0.11-0.44) | 0.55 (0.26-0.81) | 0.31 (0.13-0.52) | 0.003 |

| SOFA score | 9 (5-10) | 12 (9-15) | 9.5 (6-13) | 0.002 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 23 (54.8) | 20 (90.9) | 43 (67.2) | 0.004 |

| Vasopressor need | 17 (40.5) | 20 (90.9) | 37 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| KCH criteria fulfilled | 20 (47.6) | 22 (100.0) | 42 (65.6) | <0.001 |

| Contraindications to LT, n = 52 | 9 (27.3) | 14 (73.7) | 23 (44.2) | 0.002 |

| Physiology | ||||

| pH at admission | 7.4 (7.3-7.5) | 7.3 (7.1-7.4) | 7.4 (7.3-7.4) | 0.004 |

| Lactate at admission, mmol/L | 3.3 (2.1-4.8) | 8.6 (7.1-13.0) | 4.5 (2.5-7.8) | <0.001 |

| INR at admission | 3.3 (2.3-4.4) | 5.3 (4.1-7.0) | 4.1 (2.6-5.6) | <0.001 |

| WCC at admission, ×109/L | 9.7 (5.2-14.0) | 16.0 (10.0-26.0) | 11.0 (6.1-17.0) | 0.001 |

| Ammonia level at admission, µmol/L | 92 (73-141) | 143 (96-165) | 112 (74-159) | 0.07 |

| Peak acetaminophen level, mg/L | 120 (30-322) | 270 (108-809) | 180 (30-532) | 0.04 |

| Peak lactate, mmol/L | 3.5 (2.7-5.2) | 9.6 (7.7-21.0) | 5.0 (3.0-8.8) | <0.001 |

| Peak ALT, U/L | 5175 (2552-8671) | 7448 (5890-10340) | 6646 (3017-9299) | 0.04 |

| Peak bilirubin, µmol/L | 117 (70-221) | 232 (124-290) | 151 (77-248) | 0.02 |

| Peak creatinine, µmol/L | 149 (94-266) | 188 (123-294) | 167 (102-280) | 0.28 |

| Peak urea, mmol/L | 9.7 (6.0-16.0) | 6.6 (3.3-10.0) | 9.4 (4.4-13.0) | 0.02 |

| Peak INR | 3.8 (2.3-4.6) | 7.2 (5.7-8.0) | 4.5 (3.2-6.5) | <0.001 |

| Peak WCC, ×109/L | 13.0 (10.0-17.0) | 20.0 (15.0-28.0) | 15.0 (10.0-22.0) | 0.006 |

| Peak ammonia, µmol/L | 112 (75-173) | 166 (118-193) | 130 (94-180) | 0.02 |

| Lowest pH | 7.4 (7.3-7.4) | 7.2 (7.1-7.3) | 7.3 (7.3-7.4) | <0.001 |

| Encephalopathy grade | 0.008 | |||

| Grade 0 | 9 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Grade 1 | 6 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 3 (7.1) | 1 (4.6) | 4 (6.2) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (4.6) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Grade 4 | 23 (54.8) | 20 (90.9) | 43 (67.2) | |

| Complications | ||||

| Sepsis | 8 (19.1) | 16 (72.7) | 24 (37.5) | <0.001 |

| Bowel ischemia | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | 3 (4.7) | 0.54 |

| Stroke/ICH | 1 (2.4) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (4.7) | 0.27 |

| Major bleeding | 7 (16.7) | 10 (45.4) | 17 (26.6) | 0.01 |

| Mortality | <0.001 | |||

| Died | 1 (2.4) | 12 (54.5) | 13 (20.3) | |

| Survived | 41 (97.6) | 10 (45.4) | 51 (79.7) |

NOTE:

- Data are given as median (IQR) or n (%).

Discussion

Key Findings

In this study of patients treated for acetaminophen-induced ALF, no patient received ICP monitoring or LT. In this setting, no patient died of cerebral edema–induced tonsillar herniation. Moreover, 79.7% of patients survived with medical management alone, and, of those fulfilling KCH criteria, 69.0% survived. Finally, the application of the recently modified UKRC criteria resulted in higher sensitivity and specificity for hospital mortality.

Relationship To Previous Studies

Survival rates for ALF secondary to acetaminophen overdose are well documented in the literature. At KCH, hospital survival between 1999 and 2008 in this population was 66%.11 This is in accordance with a large, prospective, multicenter study from the United States22 and slightly higher than in earlier studies.23 Other authors have reported higher survival rates up to 78%.1, 2, 15, 24, 25 In summary, these studies suggest an overall survival of 51% to 78%. Our survival was 79.7%.

In patients fulfilling KCH criteria, survival rates vary from 19% to 68% with LT2, 22, 23, 25, 26 and from 6% to 52% without LT.2, 8, 25 In our study, survival in the KCH group was 69.0% without LT.

No patient received invasive ICP monitoring during the study period. This practice is divergent from previous literature27, 28 and in accordance with modern recommendations.13 Mortality of patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy has been reported between 23% and 50%.14, 28 In our cohort, 71.1% of patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy survived without invasive ICP monitoring. This is comparable to the survival of patients treated with ICP monitoring and LT, which have a reported 10% complication rate.27

Several prognostication criteria have been developed to identify patients who are at high risk of death from acetaminophen-induced ALF. The original KCH criteria for acetaminophen-induced ALF have a low pooled sensitivity (58%) and high pooled specificity (95%) in predicting mortality.29 Using the arterial lactate modifications to the KCH criteria, our data confirm improved sensitivity but lower specificity,21 whereas when applying the current UKRC, sensitivity and specificity were substantially higher.

Finally, in contrast to current recommendations and practice,7, 13 a substantial proportion of our patients received blood products, including coagulation factors (Table 2). However, in our cohort, bleeding complications were common and severe in 26.6% of patients, which may, in part, explain this finding. Moreover, at our institution, prophylactic transfusions of blood products are used in patients with severe coagulopathy.

Implications Of Study Findings

Our results provide further evidence that medical management as described in this unique group of patients, applied in the absence of ICP monitoring, does not appear to expose patients to increased risk of cerebral edema or death. Moreover, they imply that a highly conservative treatment approach in this setting may lead to outcomes equivalent to those of centers that apply LT. In patients fulfilling KCH criteria and in those with severe encephalopathy, our mortality was comparable to any reported series. Like the KCH criteria, many prognostic tools may, therefore, not reflect recent improvements in outcome with medical management of acetaminophen overdose. In the United Kingdom, this has resulted in further modification of the criteria for super-urgent LT,12 and the current UKRC may be a better predictor of mortality in this patient population.

Recent improvements in survival with medical therapy8 suggest that some patients undergoing LT based on existing criteria might have survived with medical management alone. Importantly, the risk of death after LT remains significant30 when compared with spontaneous recovery. In this context, our findings support the assertion that standardized medical management may be appropriate for most patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF and that the role for LT in this setting requires reevaluation.9, 11

Strengths And Limitations

Our study has several strengths. It provides novel and granular information on the modern outcome of acetaminophen-induced ALF in the absence of any surgical component to its management. It reports data from an Australian state referral center for patients with ALF regardless of their suitability for LT. All patients were treated according to our institutional protocol, ensuring consistency and homogeneity in medical management, thereby increasing internal validity. Moreover, referral and admission criteria remained unchanged during the study period, further reducing patient heterogeneity, which may have been a problem in previous studies.31, 32 Finally, definitions of ALF, KCH, and UKRC are objectively verifiable, and cerebral edema and mortality are patient-centered outcomes, unlikely to be affected by selection, ascertainment, and performance bias.

Our study has the inherent limitations of retrospective observational studies. However, acetaminophen-induced ALF is a relatively rare disease, and its diagnosis is rarely in question. Furthermore, all outcome data were extracted from the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Adult Patient Database, a high-quality, published, and monitored database.18 Our study population is limited in size, and therefore, we were not able to perform extensive exploratory analyses to identify predictors of outcome. However, our key observations are clear, and the outcomes reported are objective and patient centered. Finally, we describe the outcomes in the setting of a particular approach to treatment (so-called 4-H therapy). As such, our results may not apply to centers that do not use such an approach.

In conclusion, in a center applying a restrictive transplantation policy to the treatment of acetaminophen-induced ALF over 6 years, no patient received ICP monitoring or LT. However, overall survival was 79.7%, and survival for patients fulfilling KCH criteria was higher than in equivalent patients treated in a more liberal transplantation setting. These findings suggest that a restrictive approach to ICP monitoring and LT may be at least equivalent to conventional management in terms of patient outcomes. Finally, the current UKRC may be a better predictor of mortality in patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF.

Potential conflict of interest

Nothing to report.