Liver transplant outcomes using ideal donation after circulatory death livers are superior to using older donation after brain death donor livers

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abstract

Multiple reports have demonstrated that liver transplantation following donation after circulatory death (DCD) is associated with poorer outcomes when compared with liver transplantation from donation after brain death (DBD) donors. We hypothesized that carefully selected, underutilized DCD livers recovered from younger donors have excellent outcomes. We performed a retrospective study of the United Network for Organ Sharing database to determine graft survivals for patients who received liver transplants from DBD donors of age ≥ 60 years, DBD donors < 60 years, and DCD donors < 50 years of age. Between January 2002 and December 2014, 52,271 liver transplants were performed in the United States. Of these, 41,181 (78.8%) underwent transplantation with livers from DBD donors of age < 60 years, 8905 (17.0%) from DBD donors ≥ 60 years old, and 2195 (4.2%) livers from DCD donors < 50 years of age. DCD livers of age < 50 years with < 6 hours of cold ischemia time (CIT) had superior graft survival when compared with DBD livers ≥ age 60 years (P < 0.001). In 2014, there were 133 discarded DCD livers; of these, 111 (83.4%) were from donors < age 50 years old. Young DCD donor livers (age < 50 years old) with short CITs yield results better than that seen with DBD livers > 60 years old. Careful donor organ and recipient selection can lead to excellent results, despite previous reports suggesting otherwise. Increased acceptance of these DCD livers would lead to shorter wait list times and increased national liver transplant rates. Liver Transplantation 22 1197–1204 2016 AASLD

Abbreviations

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CIT

-

- cold ischemia time

-

- DBD

-

- donation after brain death

-

- DCD

-

- donation after circulatory death

-

- ICU

-

- intensive care unit

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- NS

-

- not significant

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- UNOS

-

- United Network for Organ Sharing

-

- WIT

-

- warm ischemia time

There exists a vast disparity between the number of patients on the liver transplant waiting list and the number of available organs.1-4 One method for increasing the number of transplantable organs has been to use organs from patients who die after circulatory death.5-9 Accordingly, large increases in the number of transplantable kidneys have resulted from donation after circulatory death (DCD) protocols. However, only modest increases in DCD liver transplantation have been observed.5, 10, 11 In fact, only approximately 6% of liver transplants in the United States are performed using DCD livers.12 This lack of growth in the DCD liver pool is due, in part, to the technical challenges of the operation and concern for postoperative complications such as ischemic cholangiopathy.5, 6

As described by Feng et al.,13 not all donor livers yield equivalent recipient outcomes. Much like livers that are recovered from donation after brain death (DBD) donors, DCD livers carry a spectrum of risk. That is, there are some livers which likely function better than others. It is known that the age of the DCD donor is a risk factor for graft loss when compared with DBD organs, particularly when the DCD donor is >50 years of age.13, 14 In addition, cold ischemia time (CIT) has been shown to have a greater effect on DCD, in contrast to livers recovered from DBD donors.13 We sought to determine if a subset of “better” DCD livers demonstrated similar outcomes to patients who underwent DBD liver transplantation. Thus, we hypothesized that DCD livers recovered from donors < 50 years of age may have similar graft survivals when compared to DBD livers from donors > 60 years of age. In this national database analysis, we observed that younger DCD donor livers yielded recipient outcomes which were similar to the outcomes observed with using older DBD donor livers. In addition, younger DCD donor livers with short CITs (<6 hours) demonstrated superior graft survival rates when compared to that seen with older DBD donor livers.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Data Acquisition

We obtained data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) on the nation's experience with DCD liver transplantation. We performed a retrospective analysis of the UNOS data set that included 52,723 primary, solitary, deceased donor, and whole liver transplants performed between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2014. Donor and recipient demographics were analyzed. National rates of DCD transplantation and national rates of liver discards were obtained directly from UNOS.

Primary Endpoint

We sought to determine whether graft survival following liver transplantation using younger DCD donors was similar to that seen when using livers recovered from older DBD donors.

Definitions

Recipients of older DBD livers were defined as those patients receiving livers from donors ≥ 60 years of age (DBD ≥ 60 years old). Recipients of younger DBD donors were defined as those patients receiving livers from donors < 60 years of age (DBD < 60 years old). Recipients of younger DCD donors were defined as patients receiving livers from DCD donors younger than 50 years old (DCD < 50 years old). Ideal DCD donor livers were defined as younger DCD livers with CITs < 6 hours. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score reflects the laboratory MELD provided by UNOS, excluding MELD exceptions.

Statistical Analysis

Graft survival was determined among the groups using Kaplan-Meier analyses. We determined actuarial patient and graft survival rates. Primary diagnosis of liver failure was included as a study variable. Accordingly, and to simplify the analysis, UNOS multiple codes (alpha-1-antitrypsin, hepatitis A, B, C, etc.) were recategorized into 1 of 5 groups: acute hepatic necrosis, cholestatic cirrhosis, noncholestatic cirrhosis, metabolic, and malignancy. Actuarial survival estimates were calculated using Kaplan-Meier life table analysis.15 Cox regression models were constructed to compare risk factors of 1- and 5-year allograft failure. Variables that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model. In our primary analyses, multivariate models were constructed using patients with complete data. In order to demonstrate that eliminating patients with incomplete data did not significantly affect the primary relationships of interest, we conducted sensitivity analyses with multiple imputations of missing covariates for variables missing >5% of the data. Sensitivity analyses were performed in which missing values were imputed using values corresponding to the 90%, 10%, and mean among patients who did have data for these variables. These secondary analyses demonstrated similar results when compared with the primary analyses and are not included in this report. Variables were compared among groups using 1-way analysis of variance, t tests, and chi-square tests as appropriate. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patients

We identified 52,271 patients who underwent primary liver transplantation with livers recovered from either DBD or DCD donors < 50 years old. Of these 52,271 patients, 41,181 (78.8%) underwent transplant with livers from DBD donors < 60 years of age, and 8905 (17.0%) received livers from DBD donors ≥ 60 years of age. The remaining 2185 (4.2%) livers were from DCD donors who were <50 years of age. Donor and recipient characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Donors in the DBD < 60-year-old and DCD < 50-year-old groups were more likely to be male (P < 0.001). Those donors in the DCD < 50-year-old group were more likely to be Caucasian (P < 0.001). There were no differences in mean CITs among any of the 3 donor groups (P = 0.543).

| DBD Livers | DCD Livers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 Years Old (n = 41,181) | ≥60 Years Old (n = 8905) | <50 Years Old (n = 2185) | P Value | |

| Donor age, years, mean (SD) | 37.4 (13.7) | 67.2 (5.9) | 30.1 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Donor sex, female, n (%) | 16,198 (39.3) | 4482 (50.3) | 686 (31.4) | <0.001 |

| Donor race, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 26,773 (65.1) | 6483 (72.8) | 1826 (83.5) | |

| Black | 7321 (17.8) | 1284 (14.4) | 177 (8.1) | |

| Other | 7127 (17.3) | 1138 (12.8) | 182 (8.4) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.2 (6.2) | 27.6 (5.9) | 26.1 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| CIT, hours, mean (SD) | 7.00 (3.3) | 7.11 (3.3) | 6.8 (3.4) | 0.543 |

- NOTE: Younger DCD livers made up only 4.2% of the livers that were analyzed.

| DBD Livers | DCD Livers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 Years Old (n = 41,181) | ≥60 Years Old (n = 8905) | <50 Years Old (n = 2185) | P Value | |

| Recipient age, years, mean (SD) | 53.9 (10.0) | 55.9 (9.4) | 54.97 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Donor sex, female, n (%) | 13,089 (31.8) | 3075 (41.6) | 669 (30.6) | <0.001 |

| Recipient race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 29,619 (71.9) | 6517 (73.2) | 1597 (73.1) | <0.001 |

| Black | 3939 (10.0) | 677 (7.6) | 213 (9.7) | |

| Other | 7623 (18.1) | 1711 (19.2) | 375 (17.2) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.5 (5.7) | 28.4 (5.7) | 28.2 (5.4) | 0.101 |

| MELD score, mean (SD) | 21.7 (10.4) | 19.7 (9.4) | 19.4 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| On ventilation, n (%) | 2184 (5.3) | 336 (3.8) | 81 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Location at time of transplant, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ICU | 5027 (12.2) | 814 (9.1) | 167 (7.6) | |

| Hospital, non-ICU | 7252 (17.6) | 1277 (14.3) | 293 (13.4) | |

| Not in hospital | 28,819 (70.0) | 6797 (76.3) | 1726 (79.0) | |

| Primary diagnosis of liver disease, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Acute hepatic necrosis | 2163 (5.3) | 329 (3.7) | 70 (3.2) | |

| Cholestatic cirrhosis | 2980 (7.3) | 744 (8.4) | 139 (6.4) | |

| Noncholestatic cirrhosis | 25,651 (62.5) | 5343 (60.3) | 1322 (60.7) | |

| Metablolic liver disease | 1107 (2.7) | 247 (2.8) | 52 (2.4) | |

| Malignancy | 9126 (22.2) | 2201 (24.8) | 594 (27.3) | |

- NOTE: MELD score was higher in the younger brain dead liver recipient.

The recipients of the DBD livers < 60 years of age were younger and more likely to be African American than were recipients of DBD livers ≥ 60 year old or DCD livers < 50 year old (P < 0.001). Recipients of livers from the DBD < 60-year-old group were more likely to be on the ventilator and have a higher MELD score at the time of transplantation (P < 0.001). All recipients were most likely to be called in from home versus admitted to the hospital at the time of transplantation. Additionally, noncholestatic cirrhosis, followed by malignancy were the most common primary diagnoses leading to transplantation.

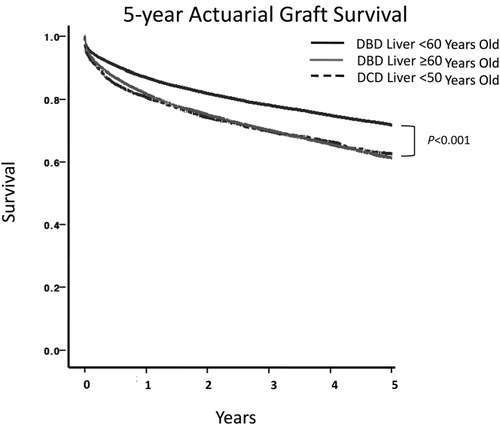

Graft Survival

Overall 5-year actuarial graft survival (Fig. 1) was significantly lower for recipients in the DCD < 50-year-old group compared to the DBD < 60-year-old group (61% versus 70%; P < 0.001). However, the actuarial 5-year graft survival for recipients in the DCD < 50-year-old group was similar to the graft survival for recipients in the DBD > 60-year-old group (63% versus 61%; P = NS).

Overall 5-year actuarial graft survival. Five-year actuarial graft survival when liver donors were <60 years of age, ≥ 60 years of age, and when DCD liver donors were <50 years of age. Graft survival for patients who received younger brain dead donor livers was higher than both older brain dead livers and DCD livers (P < 0.001).

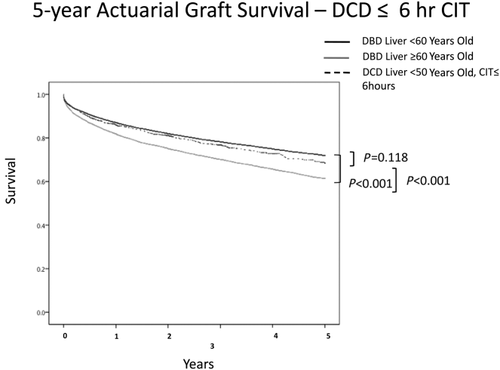

Ideal DCD Donors Perform Better Then DBD Donors ≥ 60 Years of Age

DCD livers with age < 50 years carried a higher rate of overall graft failure. However, the risk of graft failure was lower for those patients receiving a DCD liver with CIT ≤ 6 hours when compared with DBD livers ≥ 60 years of age. Five-year actuarial liver graft survival for ideal DCD donors (younger than 50 years old and with a CIT ≤ 6 hours) showed comparable graft survival to younger DBD donors (P = 0.118) and improved graft survival over older DBD donors (Fig. 2).

Five-year actuarial survival controlling for CIT. When DCD donors were < 50 years old and CIT was ≤ 6 hours, graft survival was similar (P = 0.118) to DBD graft survival even when the patients were <60 years old. Older brain dead donor livers functioned less well than both other groups.

Risk Factors for Graft Loss

A multivariate analysis using both donor and recipient characteristics was performed, and the results are listed in Table 3. Using recipients of DBD < 60 years old as the reference group, we found that recipient age, African American race, MELD score at time of transplant, pretransplant ventilator support, CIT, DBD liver ≥ 60 years old and DCD liver < 50 years old with and without CIT < 6 hours were independent predictors of graft loss. Ventilator status at the time of transplantation conferred a 52% increased risk of graft failure, whereas MELD score was associated with a 0.4% increased risk of graft failure per point increase in MELD score (P < 0.001). Cholestatic liver disease was associated with increased risk of recipient graft failure. In addition, patients who presented to transplant with a malignancy had a 62% increased risk of graft loss. Recipients of a DBD liver with age ≥ 60 years had a 47% increased risk of failure. This observation was similar to the 46% increased risk of graft loss seen when donors were DCD < 50 years old. However, there was only a 19% increased risk of graft loss in ideal DCD donors. Accordingly, the relative risk of graft loss for the ideal DCD donor was better than the risk of graft loss in older DBD donors.

| Variable | Multivariate | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient variables | ||

| Primary diagnosis of liver disease | ||

| Acute hepatic necrosis | Reference | — |

| Cholestatic cirrhosis | NS | NS |

| Noncholestatic cirrhosis | 1.339 (1.219-1.470) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic liver disease | NS | NS |

| Malignancy | 1.620 (1.463-1.794) | <0.001 |

| MELD score | 1.004 (1.002-1.007) | <0.001 |

| Recipient age | 1.009 (1.007-1.011) | <0.001 |

| Ventilator support | 1.518 (1.383-1.666) | <0.001 |

| African American recipient | 1.420 (1.341-1.503) | <0.001 |

| Location at transplant | ||

| Not in hospital | Reference | — |

| Hospital, non-ICU | 1.189 (1.124-1.259) | <0.001 |

| ICU | 1.422 (1.313-1.539) | <0.001 |

| Donor variables | ||

| BMI donor | 1.004 (1.001-1.007) | 0.009 |

| CIT | 1.024 (1.019-1.029) | <0.001 |

| DBD liver < 60 years old | Reference | — |

| DBD liver ≥ 60 years old | 1.470 (1.406-1.536) | <0.001 |

| DCD liver < 50 years old | 1.461 (1.345-1.588) | <0.001 |

| DCD liver < 50 years old (CIT ≤ 6 hours) | 1.193 (1.045-1.362) | 0.009 |

- NOTE: Shorter CIT was predictive of improved outcomes for DCD donors. DCD donor livers from donors younger than 50 years old and who have short CITs yield acceptable recipient graft survivals.

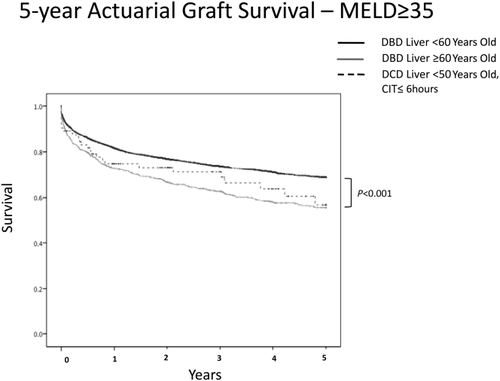

DCD for Recipients With MELD Scores ≥ 35

We next sought to determine if high recipient MELD scores changed the observation that ideal DCD donors and older DBD donors yielded similar graft survivals. Despite a MELD score ≥ 35 at the time of transplantation, there was no difference in recipient graft survivals between younger DCD donors with short CITs and older DBD donors. However, younger brain dead donors yielded the best outcomes (P < 0.001; Fig. 3).

MELD score and graft survival. Although younger brain dead donor livers performed the best, there was no difference in recipient outcome when younger DCD donors were compared with older brain dead donors.

Potential Number of Transplantable Livers

After querying the UNOS database, we observed that the number of DCD liver donors increased from 1107 to 1291 (increase of 16%) between the years 2012 and 2014. The number of liver donors increased yearly (Table 4). In 2014 alone, there were 133 discarded DCD livers (Table 5). Of these 133 livers, the vast majority were from donors who were <50 years of age (n = 111; 83.4% of all discard livers in 2014). Next, we investigated the reasons that livers that were recovered for transplant were later discarded. As shown in Table6, the most common reason for discarding a liver was donor warm ischemia time (WIT). Excluding livers discarded for biopsy findings (n = 21), anatomic abnormalities (n = 10), and recipients determined unsuitable for transplant (n = 8), we observed that an additional 77 DCD livers may have been transplantable in 2014.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total DCD donors | 1107 | 1206 | 1291 |

| DCD recovered | 388 | 427 | 496 |

| DCD transplanted | 263 | 309 | 363 |

| Balance, (%)a | 125 (32) | 118 (28) | 133 (27) |

- NOTE: All data obtained directly from UNOS.

- a Balance = DCD recovered minus DCD transplanted.

| Transplanted Livers | Discarded Livers | All Livers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor age (<50 years) | 315 (73.9) | 111 (26.1) | 426 (100) |

| Donor age (≥50 years) | 48 (68.6) | 22 (31.4) | 70 (100) |

| Total | 363 (73.2) | 133 (26.8) | 496 (100) |

- NOTE: All data obtained directly from UNOS. All data are given as n (%).

| Donor Age (<50 years) | Donor Age (≥50 years) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WIT too long | 34 (30.6) | 5 (22.7) | 39 (29.3) |

| Other | 26 (23.4) | 5 (22.7) | 31 (23.3) |

| Biopsy findings | 21 (18.9) | 4 (18.2) | 25 (18.8) |

| Anatomical abnormalities | 10 (9) | 1 (4.5) | 11 (8.3) |

| No recipient located, list exhausted | 8 (7.2) | 1 (4.5) | 9 (6.8) |

| Recipient determined to be unsuitable for transplantation in OR | 3 (2.7) | 3 (13.6) | 6 (4.5) |

| Poor organ function | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.3) |

| Diseased organ | 3 (2.7) | 1 (4.5) | 4 (3) |

| Too old on ice | 1 (0.9) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (1.5) |

| Donor medical history | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) |

| Organ trauma | 1 (0.9) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (1.5) |

| Total | 111 (100) | 22 (100) | 133 (100) |

- NOTE: All data obtained directly from UNOS. All data are given as n (%).

Discussion

Although the utilization of DCD livers allows more patients on the waiting list to get transplanted, multiple single-center and national database studies have demonstrated that outcomes after DCD liver transplantation are worse than outcomes for liver transplants using DBD donor livers.5, 6, 12 A significant contributor to allograft loss in DCD liver transplants is the development of ischemic cholangiopathy. In 2005, Foley et al.6 published a single-center experience with DCD liver transplantation. The authors observed an overall biliary stricture rate of 33% at 1 year in those patients with a DCD liver transplant, in contrast to only 10% for those with a DBD transplant. Other investigators have also seen significantly higher rates of ischemic cholangiopathy in DCD liver transplant recipients.4, 16, 17 For these reasons, many transplant centers have shied away from using DCD livers.

Feng et al.13 published an index of donor risk for liver transplantation. Of all the donor risk factors that were studied, DCD status was one of the strongest predictors of graft failure. Additionally, increasing donor age was associated with graft failure, particularly beyond 60 years of age. Thus, a perception exists that older DBD livers and DCD livers of any age are considered marginal livers. However, many centers would accept a DBD donor liver over the age of 60 years old but are reluctant to accept a DCD donor liver. The present study takes this analysis 1 step further to assess whether there exists a combination of factors that would constitute an ideal DCD donor liver and yield posttransplant outcomes that are comparable or even better than that seen with DBD donor livers.

We retrospectively analyzed the UNOS database to determine if there were a group of livers from DCD donors that functioned as well, or better, than livers from DBD donors. We found that although DCD donor livers demonstrated inferior overall graft survival when compared to DBD donor livers, younger DCD donor livers had equivalent outcomes when compared to DBD livers ≥ 60 years of age. These data are important for informing the decision of whether or not to proceed to transplantation with a DCD organ. Indeed, more liver transplants each year in the United States could be performed if more young DCD liver offers were accepted.

We also performed a multivariate analysis of previously studied recipient risk factors, inclusive of location at the time of transplant (intensive care unit [ICU] versus non-ICU) as well as primary diagnosis of liver failure. All hospital inpatients (ICU and non-ICU), recipients with cholestatic cirrhosis, and recipients with malignancy were statistically more likely to experience graft failure. However, it should be noted that the clinical differences observed in each of these groups (Table 2) was minimal.

In 2008, Selck et al.5 published that the 1- and 3-year graft survivals for DBD liver transplantation were 84% and 74% versus 74% and 58% for DCD liver transplantation. The authors did not stratify graft survival by donor age, however, nor did they include CIT into their analysis. In 2011, Bellingham et al.7 also observed significantly lower patient survivals in those who underwent DCD liver transplants. In that study, liver graft survival at 1 and 3 years for DBD liver transplantation recipients was 86.2% and 79.7% versus 69.4% versus 59.6%, for DCD recipients, respectively.

Most recently, Doyle et al.23 published in 2015 a single-center experience with DCD liver transplantation. Investigators compared 49 patients who underwent DCD liver transplantation with 98 patients who underwent DBD liver transplantation. These 98 patients were propensity-matched for recipient age, sex, cause of liver failure, cold and standard WITs, and physiologic MELD scores. Likely because of improvements in technique and patient selection over the last decade, Doyle et al. observed improved rates of ischemic cholangiopathy (8.5%), when compared with the aforementioned studies.

As presented above, prior authors have suggested that DCD liver transplants yield outcomes worse than DBD. Similar to others, we also found that not all donor livers are created equally.18 Indeed, there is a spectrum of risk associated with DCD livers. However, it should be noted that younger donor livers, particularly those that can be transplanted quickly, yield results comparable or better than some DBD grafts. The national data presented here help to clarify which DCD livers are safe to use and may lead to better outcomes than that seen with older DBD livers.19, 20

Our data have important implications for physicians accepting organ offers. Practically, these data suggest that accepting a younger locoregional DCD donor offer is as good, or better, than accepting an older brain dead donor liver offer. In addition, and because few data exist analyzing the effect of DCD on recipient graft survival in the sickest recipients, we sought to determine whether our data pertained to patients with higher MELD scores. These data are particularly important in the “Share 35” era when sicker patients are transplanted more frequently. As such, we sought to characterize recipient outcomes based on a MELD score of 35 or greater. Although DCD liver transplant outcomes were not better than DBD, we observed that DCD donors performed equivalently when compared with older brain dead donors. Taken together, our data demonstrate that DCD liver transplant outcomes are no worse than older brain dead donors, even when controlling for a MELD score of 35 or greater.

Many liver transplant surgeons are justly resistant to accept DCD livers based on the historic notion that DCD grafts portend a worse outcome. However, our presented data along with other recent reports21-23 may suggest otherwise.23 This prompted us to ask the following questions: how many young DCD livers are discarded annually, and would more frequent acceptance of younger DCD livers increase the number of liver transplants in the United States? If so, this would represent an increase in the donor organ pool, using presently available organs.

To answer this question, we queried the UNOS database to determine how many of the discarded DCD livers in 2014 were from donors of age < 50 years old. We found, perhaps surprisingly, that 83% (n = 111) of discarded DCD livers were from donors who were younger than 50 years old. These data might suggest that as many as 111 livers per year could be transplanted if liver offers for young DCD livers were accepted.

This calculation is simplistic, and its analysis is challenging. Thus, we next sought to determine if there were objective and insurmountable reasons (anatomic abnormalities, biopsy findings, and unsuitable recipients) for discarding younger DCD livers. The most common cause for discard was prolonged donor WIT. Unfortunately, it is not clear how long is “too long” because these data were not available. In addition, the assessment of WITs was likely part of a complicated decision, rather than stand-alone data points.

Our findings are timely, and they are clinically relevant. Immediately prior to submission of this manuscript, our center was faced with exactly the scenario addressed by the presented data. Our potential recipient, with a physiologic MELD score of 51 attracted a liver offer for a 72-year-old DBD liver. After acceptance of the DBD liver offer, but prior to transplantation, a second offer of a 48-year-old DCD liver was presented and entertained. Our data would suggest that accepting the DCD liver offer would provide a better patient outcome. However, the unmeasured aspects of this decision included the “what if” scenario, where after turning down the DBD offer, the potential DCD liver donor did not expire quickly enough to successfully donate a liver. Indeed, this scenario occurs in 30% of cases of DCD donors from our organ procurement organization.11 On the basis of the data in this manuscript, it is reasonable for surgeons to safely entertain a DCD liver offer, even for patients with high MELD scores.

There are several limitations to the present study. Most prominently is the retrospective nature of this report and the known challenges with large database data quality. Additionally, there are variables germane to a discussion of DCD which are not captured by the database. In particular, one variable is the incidence of ischemic cholangiopathy. Although other authors have shown that ischemic cholangiopathy rates have improved,22 it is difficult to show this improvement using national data. Also important, we have focused on CIT and donor age as predictors of graft survival as described by other national database studies. Other variables are certainly important as well. To understand more completely the drivers of outcomes following DCD liver transplantation, it may be worthwhile to also consider donor WIT and macrosteatosis.24 Although there are no national standards, our transplant center limits the acceptable donor WIT for an agonal DCD donor at 30 minutes. However, during this time, there is a variable level of hypoxia and hypotension which is likely to affect the organ, and these effects are likely to portend different outcomes.4 A better understanding of how this variable level of ischemia to the liver affects outcomes is likely needed to affect graft outcomes.

Macrosteatosis is also likely a significant risk factor to the success of DCD liver transplantation. It is our practice to limit macrosteatosis in DCD livers to <30% provided that other risk factors for increased graft loss are absent. However, there are data to support that macrosteatosis > 20% portends a poor prognosis in DCD liver transplantation.24 Additionally, it would be valuable to analyze a discussion of DCD optimization to include both induction and maintenance immunosuppression. One study demonstrated that the use of thymoglobulin for induction immunosuppression resulted in a significant reduction of ischemic cholangiopathy in DCD liver recipients when compared to basiliximab.25

In summary, we found that DCD livers from younger donors yield acceptable outcomes. It is the authors’ recommendation that DCD liver status alone should not be a reason for discarding a potential donor organ. Although our data show that it is safe to accept DCD liver offers from young donors, surgeons should continue to weigh the risks and benefits of a particular organ on a recipient-by-recipient basis. An increased willingness to accept these organs could lead to significantly more liver transplants performed annually in the United States.