The new lottery ticket: Share 35

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Abbreviations

-

- DSA

-

- donor service area

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- OPO

-

- organ procurement organization

-

- PELD

-

- Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- SLKT

-

- simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation

Although regional sharing for liver transplantation for acute liver failure has been accepted for more than 25 years,1 its extension to decompensated cirrhosis has only more recently become widely adopted.2

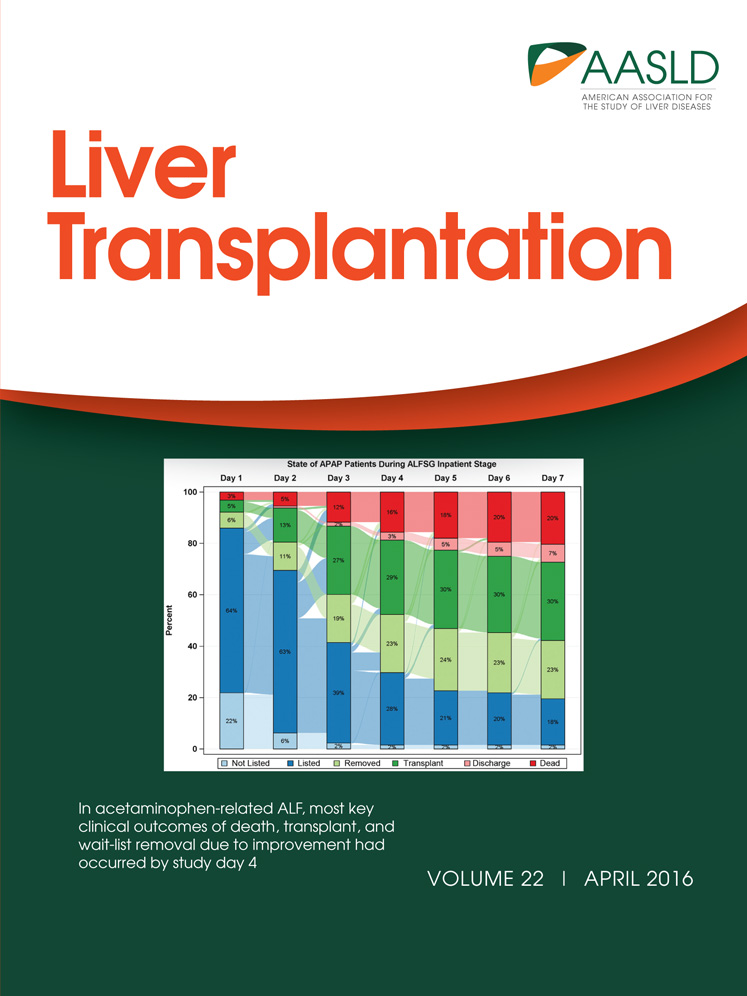

In the current issue of Liver Transplantation, Edwards et al.3 detail the results of the first 2 years of Share 35 following its implementation by the United Network for Organ Sharing. As anticipated, a greater number of candidates underwent transplantation in the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)/Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) 35+ category, with minimal changes in posttransplant mortality, graft survival, and access for pediatric and minority patients.4

So, should we, as do the authors, endorse the current, or an even wider implementation of this strategy?

First, historical precedent suggests that regional organ sharing does not reduce wait-list mortality. Share 35 is not the first effort in regional sharing for high-MELD candidates. Region 8 implemented an even broader sharing agreement for a 4-year time interval (2007-2011), sharing regionally for MELD 29+ candidates.5 An analysis of the data from this experience indicated that there was no overall reduction in wait-list mortality. Mortality reduction in the smaller group of higher MELD patients was offset by increased mortality of the much larger group of lower MELD patients. In addition, there was a marked increase in travel time and associated costs, without a net benefit.

Second, the financial implications of expanded organ sharing are significant and are not assessed in the report. A limitation of the analyses performed to date has been that they have only considered that a regional share involves additional air charter expense compared with the cost of a local donor.6, 7 In fact, for many, including in our donor service area (DSA), the standard acquisition cost for a regional donor is double that of a local donor because not only is travel cost increased, but the rules by which organ procurement organizations (OPOs) operate lead to markedly increased charges for liver donors harvested from outside the DSA.7 This calculation does not consider the significantly increased human capital expenditure for regional shares compared with a local donor or how increased travel introduces increased risk to the transplant teams.8, 9

There has been modeling to suggest that broader sharing would result in “minimal overall system cost” because sicker patients would be transplanted earlier. The first problem is that our system does not allow for savings in pretransplant care to accrue to transplant centers to offset significant increases in costs for transplantation and posttransplant care. This is a lofty idea, but even if it turned out to be true, we have no mechanism to allocate cost savings, for example, from an insurance carrier to the potential transplant center to offset policy-associated increases to overhead costs. Additionally, our allocation system is dynamic, and with Share 35, the number of people waiting at MELD scores of ≥35 increased rather than decreased following implementation of this policy.3 This issue may be a challenge should bundled payments also apply to transplant.10 Assumptions for “cost savings” on the pretransplant side will only apply should the pool of high-MELD patients diminish through a combination of MELD 35+ with the proposed redistricting plan. Unfortunately, recent publications demonstrate that quite the opposite will occur.3, 11 With an incentive to find and transplant the highest MELD patients, we see centers shifting their behaviors in listing, even if this leads to a 5% reduction in patient survival and an increase in the absolute number transplanted in this category.3

Third, MELD 35+ failed to improve clinically significant markers of performance, as reported by Edwards et al.3 Wait-list mortality did not improve, despite the significant increase in liver transplants performed in MELD 35+ recipients, which is an important observation because the goal was to decrease overall wait-list mortality by increasing the number of transplants in this sickest group (from 18.5% to 26.5% of transplants).3 Also with this policy change, there was an increase in MELD score variance at transplant, despite implementation of a policy that the community was led to believe decreases this variance. The number of transplants in the Share 35+ group of patients who had exception points (ie, not for illness due to true liver failure disease severity) actually increased from 11.4% to 12.9% (of the 26.5%).

Fourth, the study showed a marked increase in simultaneous liver-kidney transplantations (SLKTs) performed under the new policy with an increase of 20% over the pre-policy change era (from 936 to 1118 SLKTs in the post-policy change era) and a 10% increase in 2015 alone. Notably, there has been a >300% increase in SLKTs since the MELD score was introduced in 2001. Unfortunately, the ever-expanding kidney waiting list, now numbering greater than 100,000, will bear a cost as measured by an increase in waiting time and a decline in the quality of donors available because SLKTs are derived largely from a younger donor population.12

A significant limitation of the current MELD 35+ system is the lack of MELD ranges for consideration of allocation. For example, a patient with a MELD of 36 in St Louis would be allocated a liver from Denver, even though there may be a recipient in Denver with a MELD of 35. It's readily accepted by all in the field that single digit MELD points cannot differentiate disease severity. Yet by not taking this factor into account, significant unnecessary travel was undertaken at substantial expense (including human manpower), although we are not provided the data regarding the extent that this occurred. Appropriate local use of organs in transplantation should always override long distance allocation, other factors being equal, as utility is optimized. Cost and the value proposition have become a major area of focus in our health care system today. These issues cannot be ignored in any sector of medicine, including transplantation.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, the MELD 35+ allocation policy encourages behavioral changes that undermine the goals of extended regional organ sharing, reflected in the significant increase in the number of MELD/PELD 35+ list additions. Instead of reducing the median MELD at transplant over the two years of this policy the median MELD at transplant actually increased, from MELD 27 pre-MELD 35+ to MELD 28 in the share 35 era.

At the end of the day, we all strive for an allocation system that best provides for the optimal utility of a scarce resource. However, significant concerns exist that expanded implementation of Share 35 will not achieve this goal. We need to understand and address the many faulty parts of our current allocation system before we begin to contemplate the systemic overhaul of redistricting. We have many recent changes to appreciate first, such as the revised hepatocellular carcinoma exception scores, a proposed national review board to standardize MELD score exception points, and MELD score plus sodium allocation changes. We also need to see studies on the impact of these changes on vulnerable populations, including women.

Additionally, we must seriously consider the substantial negative impact of shifting to a system where it is estimated that 84% of livers would travel by air.13 This will have a profound impact on disrupting the beneficial relationship that encourages innovation between transplant centers and local OPOs.14 Our efforts to increase organ donation must be the major focus of our current efforts, as some portions of the country have so effectively proven.15 Implementation of redistricting will shift the attention of OPOs and transplant centers to logistics and will result in an overall decrease in liver transplants, as predicted by liver-simulated allocation modeling. However, should we change the rules and alter the distribution for who gets the offer, are we not changing where the lifesaving chance exists, or as my patient said, “So you're wanting me to live long enough so I might get sick enough to win.” These words sum up the Share 35 lottery.

-

William C. Chapman, M.D.

-

Department of Surgery

-

Washington University in St. Louis

-

St. Louis, MO