Daclatasvir combined with sofosbuvir or simeprevir in liver transplant recipients with severe recurrent hepatitis C infection

Bristol-Myers Squibb provided daclatasvir for all study participants as well as financial support for the data analysis and publications.

Robert J. Fontana has received grants from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Vertex. Robert S. Brown Jr has received grants/personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, and Janssen. Maria-Carlota Londoño has served as a speaker/advisor and has received personal/honorarium fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, MSD, Gilead, and AbbVie. Rudolf E. Stauber has received grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, and MSD. Peter Ferenci has received grants/personal fees from Gilead and Roche; personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, AbbVie; and a patent from Madaus-Rottapharm. Carlo Torti has received grants/personal fees for serving as a speaker and conference participant for Gilead and AbbVie. Christine M. Durand has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead for clinical trials and advisory boards. Ola Weiland has received personal fees for serving as a speaker/advisor for AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Roche, Merck, Medivir, and Novartis. Ahmed M. ElSharkawy has received personal fees from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Gilead. Stephan Stenmark has received free medication for patients in the compassionate use program from Bristol-Myers Squibb. K. Rajender Reddy served on the advisory board of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, and Janssen and has received research support (money paid to the Institution) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Merck, AbbVie, and Janssen. Francis Vekeman, Raluca Ionescu-Ittu, and Bruno Emond are employees of Analysis Group, Inc, which has received consultancy fees from MediTech Media, Ltd., funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb to design the study and conduct data analyses. Ana Moreno-Zamora, Martin Prieto, Shobha Joshi, Kerstin Herzer, Kristina R. Chacko, Viola Knop, Syed-Mohammed Jafri, Lluís Castells, Laura Loiacono, Raffaella Lionetti, Ranjeeta Bahirwani, Abdullah Mubarak, Bernhard Stadler, Marzia Montalbano, Christoph Berg, and Adriano M. Pellicelli have no conflicts to disclose.

Robert J. Fontana and K. Rajender Reddy participated in study concept and design, data collection and analysis, writing, and critical review of the manuscript. Francis Vekeman, Raluca Ionescu-Ittu, and Bruno Emond conducted the statistical analyses and participated in study concept and design, data collection, and the writing and critical review of the manuscript. All authors contributed patient data, reviewed manuscript drafts, and reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

The authors are fully responsible for all the content and editorial decisions in this manuscript.

Abstract

Daclatasvir (DCV) is a potent, pangenotypic nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor with demonstrated antiviral efficacy when combined with sofosbuvir (SOF) or simeprevir (SMV) with or without ribavirin (RBV) in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Herein, we report efficacy and safety data for DCV-based all-oral antiviral therapy in liver transplantation (LT) recipients with severe recurrent HCV. DCV at 60 mg/day was administered for up to 24 weeks as part of a compassionate use protocol. The study included 97 LT recipients with a mean age of 59.3 ± 8.2 years; 93% had genotype 1 HCV and 31% had biopsy-proven cirrhosis between the time of LT and the initiation of DCV. The mean Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was 13.0 ± 6.0, and the proportion with Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) A/B/C was 51%/31%/12%, respectively. Mean HCV RNA at DCV initiation was 14.3 × 6 log10 IU/mL, and 37% had severe cholestatic HCV infection. Antiviral regimens were selected by the local investigator and included DCV+SOF (n = 77), DCV+SMV (n = 18), and DCV+SMV+SOF (n = 2); 35% overall received RBV. At the end of treatment (EOT) and 12 weeks after EOT, 88 (91%) and 84 (87%) patients, respectively, were HCV RNA negative or had levels <43 IU/mL. CTP and MELD scores significantly improved between DCV-based treatment initiation and last contact. Three virological breakthroughs and 2 relapses occurred in patients treated with DCV+SMV with or without RBV. None of the 8 patient deaths (6 during and 2 after therapy) were attributed to therapy. In conclusion, DCV-based all-oral antiviral therapy was well tolerated and resulted in a high sustained virological response in LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection. Most treated patients experienced stabilization or improvement in their clinical status. Liver Transplantation 22 446-458 2016 AASLD

Abbreviations

-

- AE

-

- adverse event

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- BL

-

- baseline

-

- CTP

-

- Child-Turcotte-Pugh

-

- CYP3A4

-

- cytochrome P450 3A4

-

- DCV

-

- daclatasvir

-

- EOT

-

- end of treatment

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- INR

-

- international normalized ratio

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- NA

-

- not applicable

-

- ND

-

- not detectable

-

- NR

-

- not reported

-

- NS5A

-

- nonstructural protein 5A

-

- OATPB

-

- organic anion-transporting polypeptide B

-

- RBV

-

- ribavirin

-

- SAE

-

- serious adverse event

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- SMV

-

- simeprevir

-

- SOF

-

- sofosbuvir

-

- SVR

-

- sustained virological response

-

- SVR12

-

- sustained virological response at ≥12 weeks

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)–related end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma are the leading indications for liver transplantation (LT) in North American and European adults.1, 2 Although HCV LT recipients generally do well, recurrent HCV infection in the allograft is nearly universal and leads to a lower 3- and 5-year survival in these patients compared with that in non-HCV LT recipients.3-5 HCV recurrence can not only lead to accelerated allograft inflammation and fibrosis, but also to rapidly progressive liver failure that is frequently refractory to standard antiviral therapy.6, 7

Interferon-based antiviral therapy is difficult to administer to LT recipients and is associated with a low rate of sustained virological response (SVR).8, 9 However, LT recipients who achieve SVR with antiviral therapy have a markedly improved survival compared with nonresponders.10 Combination oral antiviral therapy was shown to be associated with higher rates of SVR and improved tolerability compared with historical outcomes of interferon-based regimens in LT recipients.11, 12 For example, a 24-week course of sofosbuvir (SOF) and ribavirin (RBV) can lead to an SVR in up to 70% of patients with compensated HCV genotype 1 or 3.12 In addition, SOF- and RBV-based salvage therapy has proven effective in some LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV, including those with severe cholestatic HCV and decompensated cirrhosis.13 The combination of SOF and the potent nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) inhibitor daclatasvir (DCV), with or without RBV, holds even greater promise as a pangenotypic regimen for difficult-to-treat patients with HCV.14, 15 Preliminary data have suggested that the DCV+SOF regimen may be safe and effective in LT candidates and recipients with varying severity of liver disease.16-18 The utility of DCV combined with simeprevir (SMV) and RBV among LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection, however, is largely unknown. The aim of the current study was to describe the efficacy and safety of a 24-week DCV-based all-oral combination antiviral regimen in 97 LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection enrolled into a single patient investigational new drug protocol at multiple sites in Europe and North America.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Patients enrolled in this program received DCV provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ). Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age and were required to have a severe, life-threatening HCV infection with an anticipated survival of <12 months. Patients were also required to have had an LT before initiating DCV-based therapy and to complete ≥12 weeks of follow-up after therapy. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of good clinical practice and was approved by local institutional review boards. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design

This was a retrospective study wherein patient charts were abstracted by the investigators at the local sites. Patients received 60 mg of DCV once daily for up to 24 weeks in combination with other oral antiviral medications that were selected by the treating physician. In addition, the inclusion of RBV and its dose was determined by the site investigator on a case-by-case basis. Selection of SOF or SMV may have been influenced by individual drug approvals in the United States and Europe: SOF was approved for the treatment of HCV in the United States and Europe in December 2013 and January 2014, respectively, and SMV was available for the treatment of HCV after approval in November 2013 and May 2014, respectively.19, 20 For analyses of virological response, baseline (BL) HCV RNA was defined as the most recent HCV RNA measurement before start of DCV-based therapy (if not available, the first measurement after the start of therapy was used), end of treatment (EOT) HCV RNA was defined as the closest measurement to the end date of the DCV-based therapy, and sustained virological response at ≥12 weeks (SVR12) was defined as the first measurement of HCV RNA ≥ 12 weeks after EOT.

Efficacy and Safety Assessments

Local efficacy and safety laboratory results as well as clinical data were obtained by a data coordinating center (Analysis Group, Inc.) using an electronic case report form. HCV RNA was measured at individual institutions using locally available HCV RNA assays. Notably, pretreatment assessment and/or EOT assessment (in patients with virological breakthrough or relapse) for resistance-associated variants conferring reduced efficacy to SOF, DCV, and SMV was not performed. Virological breakthrough during DCV-based treatment was defined as confirmed detectable HCV RNA ≥ 43 IU/mL after having previously achieved undetectable HCV RNA while on treatment. Relapse was defined as confirmed detectable HCV RNA ≥ 43 IU/mL after having achieved undetectable HCV RNA or HCV RNA < 43 IU/mL at EOT. Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores at start of DCV-based therapy, EOT, and last contact were calculated based on laboratory data provided by the local institutions. Status of biopsy-proven cirrhosis between LT and initiation of DCV-based therapy was reported by local investigators. The clinical diagnosis of severe cholestatic HCV was based on the presence of high levels of serum HCV RNA and cholestasis in the absence of known biliary obstruction.21 A liver biopsy to confirm the histological diagnosis of severe cholestatic HCV was not required for entry into this study.

Safety was evaluated by clinical laboratory tests, physical examination, measurement of vital signs, and documentation of adverse events (AEs). Prespecified serious adverse events (SAEs) of interest, including deaths, hospitalizations, and rejection, were reported by the investigators.

Statistical Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint for this study was the proportion of patients who achieved SVR12 after the end of DCV-based therapy. Other efficacy endpoints included EOT virological response, virological breakthrough, and virological relapse. The principal safety endpoints were the frequencies of deaths, hospitalizations, and rejection episodes during and after treatment. Patient characteristics were described using means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables as well as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. The DCV-based regimen received and the virological response, virological breakthrough, and virological relapse outcomes were reported as frequencies and proportions. Patient characteristics and virological outcomes were reported overall and stratified by treatment regimen (DCV+SOF with or without RBV and DCV+SMV with or without RBV) and presence or absence of severe cholestatic HCV, biopsy-proven cirrhosis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection. Changes in CTP and MELD scores from BL to last contact were reported stratified by the BL CTP and MELD scores. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

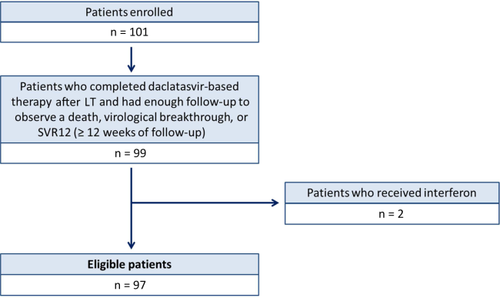

A total of 101 patients were enrolled by 26 investigators in Europe (69%) and North America (31%) between October 2010 and August 2014. Ninety-seven LT recipients satisfied the study inclusion criteria: (1) they received a DCV-based oral antiviral therapy regimen that did not include interferon after LT and (2) they either died on treatment, had a virological breakthrough, or had at least 12 weeks of follow-up to assess SVR (Fig. 1). Nearly all patients (93%) had HCV genotype 1 infection (Table 1). Most patients were male (67%) and had a mean age of 59.3 ± 8.2 years. Severe cholestatic HCV infection and biopsy-proven cirrhosis were present at BL in 37% and 31% of patients, respectively (Table 1). Patients with severe cholestatic HCV infection had high serum levels of HCV RNA (mean, 28.1 ± 111.4 × 6 log10 IU/mL) at initiation of DCV-based therapy and a predominance of serum alkaline phosphatase (mean, 225 ± 144 IU/L) and total bilirubin (mean, 5.7 ± 9.4 mg/dL) elevations in the absence of a known biliary tract complication (Table 2). Nine patients were coinfected with HIV. A total of 5 patients had undergone 2 or more prior LTs. The mean duration between the most recent LT and the start of DCV-based therapy was 44.5 ± 55.0 months. Antiviral therapy before and after the most recent LT was received by 55% and 37% of patients, respectively (the type and duration of prior antiviral therapy received were not available). The mean CTP and MELD scores at BL were 7.0 ± 2.0 and 13.0 ± 6.0, respectively.

Study sample flow diagram. The flow diagram shows the 97 patients who were enrolled into the study and included in the final analysis.

| Patient Characteristics | All Patients (n = 97)a | DCV + SOF ± RBV (n = 77) | DCV + SMV ± RBV (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 59.3 (8.2) | 59.6 (8.4) | 58.5 (7.7) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 65 (67) | 53 (69) | 10 (56) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 79 (81) | 60 (78) | 18 (100) |

| African American | 6 (6) | 6 (8) | 0 |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 11 (11) | 11 (14) | 0 |

| Time from most recent LT to start of DCV therapy, mean (SD), months | 44.5 (55.0) | 42.7 (52.8) | 55.1 (66.1) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |||

| 1a | 38 (39) | 36 (47) | 2 (11) |

| 1b | 46 (47) | 29 (38) | 16 (89) |

| 1 (subtype unknown) | 6 (6) | 6 (8) | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| 4 | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| HCV RNA, mean (SD), × 6 log10 IU/mL | 14.3 (68.8) | 16.3 (76.9) | 7.0 (13.0) |

| ALT, mean (SD), IU/L | 142 (357) | 157 (398) | 85 (76) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, mean (SD), IU/Lb | 189 (114) | 187 (118) | 200 (104) |

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dLc | 3.8 (7.0) | 4.3 (7.7) | 1.7 (1.2) |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 11.5 (2.1) | 11.5 (2.3) | 11.7 (1.5) |

| INR, mean (SD)d | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| CTP score, mean (SD) | 7.0 (2.0) | 7.2 (2.1) | 6.6 (1.7) |

| CTP class, n (%) | |||

| A (5-6) | 49 (51) | 36 (47) | 12 (67) |

| B (7-9) | 30 (31) | 24 (31) | 5 (28) |

| C (10-15) | 12 (12) | 11 (14) | 1 (6) |

| Missing | 6 (6) | 6 (8) | 0 (0) |

| MELD score, mean (SD) | 13.0 (6.0) | 13.5 (6.3) | 11.0 (4.3) |

| Biopsy-proven cirrhosis, n (%)∥ | 30 (31) | 19 (25) | 11 (61) |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | 9 (9) | 6 (8) | 2 (11) |

| Severe cholestatic HCV, n (%) | 36 (37) | 31 (40) | 4 (22) |

| Time from LT to start of DCV therapy, mean (SD), months | 16.9 (19.5) | 17.4 (20.3) | 14.1 (15.6) |

| Hospitalized at start of DCV therapy, n (%) | 6 (6) | 6 (8) | 0 (0) |

| RBV users, n (%) | 34 (35) | 20 (26) | 12 (67) |

| Immunosuppressive drug use, n (%) | |||

| Tacrolimus | 64 (66) | 53 (69) | 9 (50) |

| Mycophenolate | 30 (31) | 23 (30) | 6 (33) |

| Prednisone | 22 (23) | 17 (22) | 5 (28) |

| Cyclosporine | 19 (20) | 13 (17) | 6 (33) |

| Everolimus | 9 (9) | 6 (8) | 3 (17) |

| Sirolimus | 4 (4) | 4 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

- a Two patients received a regimen that contained DCV, SOF, SMV, and RBV.

- b Missing values for 10 patients.

- c Missing value for 1 patient.

- d Missing values for 4 patients.

- ∥Biopsy confirmed following LT.

The choice of direct-acting oral antiviral agents used in combination with DCV was determined by the local site investigator. Most patients were treated with DCV+SOF (79%), whereas 19% received DCV+ SMV and 2% received DCV+SOF+SMV. Overall, 35% also received RBV (26% of the patients using DCV+SOF regimens and 67% of those using DCV+SMV regimens). Among the 91 patients who did not die on treatment, the median duration of treatment from the initiation of DCV-based therapy until the discontinuation of the last agent in the regimen was 24.0 weeks (range, 12.3-54.4 weeks). Median duration of treatment was 24.1 weeks (range, 16.1-28.4 weeks) for the 51 patients treated with DCV+SOF, 24.0 weeks (range, 12.4-52.1 weeks) for the 20 patients treated with DCV+SOF+RBV, 24.0 weeks (range, 12.3-54.4 weeks) for the 6 patients treated with DCV+SMV, 24.0 weeks (range, 16.3-24.1 weeks) for the 12 patients treated with DCV+SMV+RBV, and 26.7 weeks (range, 26.0-27.2 weeks) for the 2 patients treated with DCV+SMV+RBV+SOF. In the 34 patients who received RBV as part of their DCV-based therapy, the median daily dose of RBV at BL was 800 mg (range, 200-1200 mg). Fourteen patients (41%) had their RBV dose reduced, and 6 (18%) additional patients had to stop RBV during treatment.

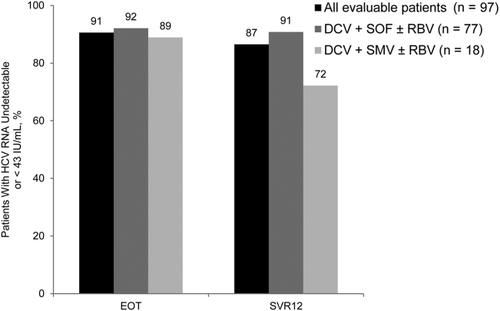

Efficacy

At the EOT and SVR12 time points, 91% and 87% of patients, respectively, had an HCV RNA level that was undetectable or <43 IU/mL (Fig. 2). EOT response was similar between the DCV+SOF (92%) and DCV+SMV (89%; P = 0.64) regimens, but SVR12 was significantly higher with the DCV+SOF regimen (91% versus 72%; P = 0.047). EOT and SVR12 outcomes for patients who did or did not have RBV in their DCV+SOF or DCV+SMV regimen are shown in Supporting Table 1. Although the stratified analysis by RBV use was limited by low numbers of patients, the addition of RBV led to a higher but nonsignificant SVR12 in those treated with DCV+SOF (100% with RBV versus 88% without RBV; P = 0.18).

Virological response rates. Rates of virological responses are shown by the EOT and SVR12. Response evaluation was performed for all 97 patients (black bars) and also by treatment regimen: DCV+SOF with or without RBV (darkly shaded gray bars) and DCV+SMV with or without RBV (lightly shaded gray bars).

Analysis of outcomes by BL characteristics demonstrated that 86% of the 36 patients with severe cholestatic HCV infection achieved SVR12 with treatment compared with 87% of those without severe cholestatic HCV infection (P > 0.99; Table 2). In addition, the rate of SVR12 was 78% in the 9 patients with HIV coinfection compared with 88% in those without HIV coinfection (P = 0.35; Supporting Table 2). Finally, SVR12 was 87% in the 30 patients with biopsy-proven cirrhosis before treatment and 87% in those without cirrhosis (P > 0.99; Supporting Table 3).

| Patients With Severe Cholestatic HCV (n = 36) | Patients Without Severe Cholestatic HCVa (n = 61) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient and disease characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 58.3 (7.8) | 59.9 (8.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 22 (61) | 43 (70) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 24 (67) | 55 (90) |

| African American | 5 (14) | 1 (2) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Other | 7 (19) | 4 (7) |

| Time from most recent LT to start of DCV therapy, mean (SD), months | 16.9 (19.5) | 60.8 (62.3) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||

| 1a | 19 (53) | 19 (31) |

| 1b | 15 (42) | 31 (51) |

| 1 (subtype unknown) | 1 (3) | 5 (8) |

| 2 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| 3 | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| 4 | 0 | 4 (7) |

| HCV RNA, mean (SD), × 6 log10 IU/mL | 28.1 (111.4) | 6.1 (12.4) |

| ALT, mean (SD), IU/L | 99 (95) | 167 (444) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, mean (SD), IU/Lb | 225 (144) | 166 (86) |

| Hemoglobin, mean (SD), g/dL | 11.4 (2.0) | 11.6 (2.2) |

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dLc | 5.7 (9.4) | 2.7 (4.9) |

| INR, mean (SD)d | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.3) |

| CTP score, mean (SD) | 7.4 (2.3) | 6.8 (1.9) |

| CTP class, n (%) | ||

| A (5-6) | 15 (42) | 34 (56) |

| B (7-9) | 11 (31) | 19 (31) |

| C (10-15) | 7 (19) | 5 (8) |

| Missing | 3 (8) | 3 (5) |

| MELD score, mean (SD) | 13.8 (7.6) | 12.5 (4.8) |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | 3 (8) | 6 (10) |

| Biopsy-proven cirrhosis, n (%)e | 6 (17) | 24 (39) |

| Hospitalized at start of DCV therapy, n (%) | 4 (11) | 2 (3) |

| DCV-based regimen, n (%) | ||

| DCV + SOF | 23 (64) | 34 (56) |

| DCV + SOF + RBV | 8 (22) | 12 (20) |

| DCV + SMV | 1 (3) | 5 (8) |

| DCV + SMV + RBV | 3 (8) | 9 (15) |

| DCV + SMV + SOF + RBV | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| RBV users | 12 (33) | 22 (36) |

| Treatment duration, mean (SD), weeks¶ | 22.5 (5.6) | 24.3 (7.4) |

| Outcomes | ||

| Deaths, n (%) | 4 (11) | 4 (7) |

| Patients with SAEs that required hospitalization, n (%) | 9 (25) | 10 (16) |

| EOT, n (%) | ||

| Undetectable | 21 (58) | 47 (77) |

| Detected, but < 43 IU/mL | 10 (28) | 10 (16) |

| Not available (any reason)g | 5 (14) | 4 (7) |

| SVR12, n (%) | ||

| Undetectable | 21 (58) | 44 (72) |

| Detected, but < 43 IU/mL | 10 (28) | 9 (15) |

| Not available (any reason)h | 5 (14) | 6 (10) |

- a Includes 2 patients with missing information for severe cholestatic HCV.

- b Missing values for 10 patients.

- c Missing value for 1 patient.

- d Missing value for 4 patients.

- e Biopsy confirmed following LT.

- f From DCV initiation until discontinuation of last drug in regimen.

- g A total of 9 patients did not have EOT data because they had a virological breakthrough (n = 3) or died (n = 6) before EOT.

- h A total of 11 patients did not have SVR12 data because they had a virological breakthrough (n = 3) or died (n = 8) before 12 weeks of follow-up after EOT.

Three patients had virological breakthrough on treatment, and 2 patients relapsed after completion of therapy (Table 3). All 5 patients with virological breakthrough or relapse were receiving DCV+SMV with or without RBV, and all had HCV genotype 1 infection. One patient who had virological breakthrough at week 12 was switched from a regimen of DCV+SMV+RBV before breakthrough to SOF+DCV+RBV at the time of the breakthrough, and then to SOF+RBV 3 weeks after the breakthrough. This patient became HCV RNA negative 11 weeks after the DCV treatment ended. A second patient had virological breakthrough at week 21 and, at the time of confirmation at week 23, stopped therapy with DCV+SMV. The patient was not retreated and was later found to have gastric cancer.

| Characteristics | Virological Breakthrough 1 | Virological Breakthrough 2 | Virological Breakthrough 3 | Relapser 1 | Relapser 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years/sex | 58/Male | 65/Female | 40/Female | 59/Male | 58/Female |

| Treatment regimen | DCV + SMV + RBV | DCV + SMV | DCV + SMV + RBV | DCV + SMV + RBV | DCV + SMV |

| Time between start of therapy and breakthrough, weeks | 12 | 21a | 16 | NA | NA |

| Time between EOT and relapse, weeks | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 8 |

| HCV genotype | 1b | 1b | 1a | 1b | 1b |

| Weeks of DCV completed | 16 | 23 | 16 | 24 | 24 |

| Biopsy-proven cirrhosis pretreatment | No | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown |

| Severe cholestatic HCV | Yes | Unknown | No | No | No |

| HCV RNA, IU/mL | |||||

| Pre-DCV therapy | 5.0 × 6 log10 | 3.1 × 6 log10 | 3.6 × 6 log10 | 4.0 × 7 log10 | 3.4 × 5 log10 |

| At EOT or when DCV stopped due to breakthrough | 9.1 × 5 log10 | 9.4 × 5 log10 | 9.4 × 5 log10 | ND | ND |

| At time of relapse | – | – | – | 13,510 | 55 |

| Last available measure | ND (11 weeks after EOT)b | 1.3 × 7 log10 (33 weeks after EOT) | 1.8 × 7 log10 (26 weeks after EOT) | ND (26 weeks after EOT)c | 15,400 (14 weeks after EOT) |

- a Confirmed at week 23.

- b After viral breakthrough, therapy was switched to SOF and RBV.

- c This patient was retreated with DCV+SOF for 24 weeks and had undetectable HCV RNA levels 16 weeks after EOT.

Liver Disease Severity

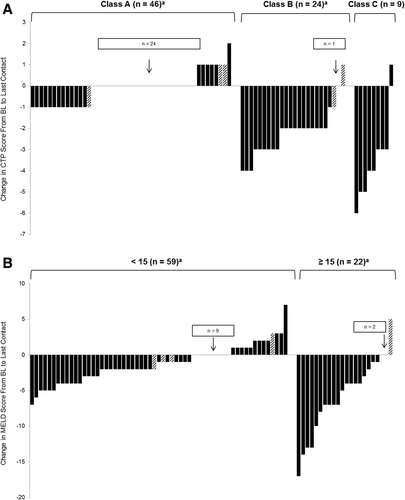

The CTP scores, MELD scores, and serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels improved in most patients with antiviral treatment. For patients with available data, the mean pretreatment CTP scores had improved from 6.8 ± 1.9 to 5.7 ± 1.2 at last contact (n = 79; P < 0.001), but 10 of 79 (13%) patients had a worsening CTP score (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the mean MELD scores improved from 12.1 ± 4.5 to 9.7 ± 3.1 (n = 81; P < 0.001), but 14 of 81 (17%) patients had a worsening MELD score (Fig. 3B). Finally, the mean serum ALT values improved from 149 ± 372 to 26 ± 18 IU/L (n = 89; P < 0.001), although there were 10 patients who had a small increase in serum ALT level (≤10 IU/L for all patients).

Change in liver disease scores. Changes in CTP and MELD scores from BL to last contact. Only patients with a BL and end-of-treatment or last-contact CTP or MELD score measure were included. (A) Patients were categorized by BL CTP class (A, B, or C). (B) Patients were categorized by BL MELD score (<15 or ≥ 15). Hatched bars indicate patients with viral breakthrough or relapse.

Safety

Twenty patients died or experienced SAEs that required hospitalization during treatment: 5 patients had an SAE hospitalization and then died; 1 patient died without a SAE-related hospitalization; and 14 patients had an SAE-related hospitalization without death (Table 4). Two additional patients died at 6 and 10 weeks after EOT. On the basis of the investigators' assessments, none of the deaths were related to the oral antiviral regimen. However, 2 of the SAE-related hospitalizations were possibly related to treatment; 1 SAE-related hospitalization involved cholangitis and renal failure occurring 10 days after the initiation of therapy (DCV+SMV+RBV), and the other hospitalization was due to a transiently elevated serum creatinine of 2.3 mg/dL occurring 4 weeks after initiation of therapy (DCV+SOF). In both patients, the DCV-based regimen was not interrupted, and patients were effectively treated for their AEs.

| Characteristics | Death 1 | Death 2 | Death 3 | Death 4 | Death 5 | Death 6 | Death 7 | Death 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years/sex | 64/Female | 57/Male | 44/Male | 75/Male | 59/Female | 51/Male | 71/Male | 58/Male |

| Treatment regimen | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SOF | DCV + SMV |

| HCV genotype | 1a | 1a | 1a | 1b | 1a | 1a | 1b | 1b |

| Weeks of DCV therapy completed | 13 | 16 | 5 | 1 day | 4 | 2 | 25 | 24 |

| Time from LT to DCV, months | 45 | 4 | 59 | 299 | 10 | 18 | 136 | 41 |

| Cause of death | Duodenalulcer | Multiorgan failure | Sepsis | Hepatic | Hepatic | Hepatic | Cerebral hematoma | Hepatic |

| Biopsy-proven cirrhosis pretreatment* | Yes | No | Unknown | Unknown | No | No | No | Yes |

| Severe cholestatic HCVb | Yes | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| CTP score/class | ||||||||

| At start of DCV therapy | 11C | 5A | 8B | 5A | 11C | 13C | 8B | 9B |

| At the time of deathc | 13C | 5A | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 7B | 7B |

| MELD score | ||||||||

| At start of DCV therapy | 26 | 6 | 21 | 19 | 33 | 40 | 17 | 21 |

| At the time of deathc | 31 | 8 | 19 | Unknown | Unknown | 44 | 12 | 7 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | ||||||||

| At start of DCV therapy | 7.5 | 1 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 22.4 | 45 | 4.5 | 3.6 |

| HCV RNA, IU/mL | ||||||||

| Pre-DCV therapy | 5.5 × 4 log10 | 4.7 × log10 | NDd | 1.1 × log10 | 4. 8 × 6 log10 | 1.2 × log10 | 1.2 × 6 log10 | NDd |

| At last measuremente | <43 | ND | NR | NR | NA | ND | <15 | ND |

- a Biopsy confirmed following LT but before DCV therapy.

- b Before DCV therapy.

- c CTP and MELD scores at the time of death could not be computed for patients who did not have further laboratory tests performed between treatment initiation and death.

- d Both patients had previously received SOF+RBV but stopped due to anemia. Patients then switched to a regimen of DCV+SOF.

- e Reported if available and at a different date.

RBV dose reductions were required in 41% of patients receiving RBV, and, overall, 6% of patients initiated erythropoietin-stimulating therapy. A serum creatinine increase >0.5 mg/dL above BL levels was noted in 20% of patients. Bacterial or fungal infections were documented in 12% of patients. No patients experienced acute rejection; however, 2 patients experienced immunosuppressant toxicity (1 with neurotoxicity and 1 with nephrotoxicity) due to high calcineurin inhibitor levels.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate a high rate of virological suppression during and after a 24-week course of DCV in combination with SOF and/or SMV, with or without RBV, in LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection. The majority of the patients in this study had HCV genotype 1 infection (93%). Additionally, more than half had received prior antiviral therapy (55%). The overall SVR12 rate of 87% was similar to the reported SVR rate (95%) observed in the phase 3 ALLY-1 study of DCV+SOF with low-dose RBV given for 12 weeks in LT recipients with compensated HCV genotype 1-6.16 The high rate of virological suppression in the current study was achieved despite 43% of the cohort having decompensated liver disease (CTP score ≥ 7), 37% having severe cholestatic HCV, and the entire cohort having a mean pretreatment MELD score of 13.0 (Table 1). In addition, the high rates of virological response in this study of LT recipients with advanced liver disease was numerically higher than that previously reported with SOF+RBV given for 24-48 weeks in LT recipients with decompensated recurrent HCV infection (60%-70%).12, 13 Similarly, a high rate of virological suppression has also been reported with ledipasvir combined with SOF and RBV in LT recipients with compensated HCV genotype 1 infection.22 Therefore, combining a potent NS5A inhibitor like DCV with SOF may be particularly useful in patients with severe recurrent HCV infection after LT.

A number of recent trials have observed high virological response with all-oral antiviral therapy in LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV.23-26 Overall, the EOT and SVR rates in our patients were high with DCV+SOF and DCV+SMV (Fig. 2). However, SVR rates were significantly higher with DCV+SOF than with DCV+SMV (91% versus 72%; P = 0.047), and all 5 of the patients with virological failure were treated with DCV+SMV with or without RBV (Table 3). The current study results compare favorably with the high EOT (99%) and SVR12 (97%) rates observed in a similar population of patients (n = 116) with severe recurrent HCV after LT who received DCV+SOF with or without RBV for 24 weeks in the Compassionate Use of Protease Inhibitors in Viral C in Liver Transplantation study.24 A high rate of virological response was also recently reported in patients with severe cholestatic HCV after LT who were treated with the same regimen for 24 weeks.25 In addition, interim results of an ongoing phase 2 study of DCV+SMV and full-dose RBV for 24 weeks in HCV genotype 1b patients with compensated recurrent HCV infection after LT, demonstrated high rates of virological response at posttreatment week 4 (91%).27 However, in contrast to our study, these patients all had clinically compensated liver disease. Because of the small number of patients in our study who received RBV, we were not able to determine whether RBV was necessary when DCV was combined with SOF or SMV (Supporting Table 1). The dose of RBV used in this study was not dictated by the protocol but rather was determined by the local site investigators. Therefore, if RBV is to be used, we recommend that the starting dose be adjusted for BL renal function and that hemoglobin levels be carefully monitored during therapy, particularly in patients with decompensated liver disease.

In addition to virological suppression, hepatic function indices were assessed in the 88 patients who completed therapy and follow-up. The mean BL serum ALT levels greatly improved in nearly all these patients (mean ALT, 149 IU/L pretreatment versus 26 IU/L at last contact; P < 0.001). In addition, most of the patients with CTP class A had stable or improved scores during follow-up (Fig. 3A), whereas 85% of patients with CTP scores of class B/C experienced a clinically significant improvement in their CTP score (ie, decrease ≥ 2) during follow-up. Similarly, the mean MELD scores of those with a BL MELD score < 15 were essentially unchanged, whereas 86% of patients with a BL MELD score of ≥ 15 had improvement in their MELD scores (Fig. 3B). However, 13% of the treated patients had an increase in their CTP score at last follow-up, but this primarily occurred in patients with CTP A scores and most of these patients only had an increase in their score by 1 point. Likewise, 17% of patients had an increase in their MELD score compared with BL, but in nearly all of these patients, the BL MELD scores were <15 and the mean increase was only 2 MELD points. Therefore, these data suggest that many LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection may experience stabilization or improvement in their overall clinical status with effective antiviral therapy.13

In addition to indicating that DCV-based therapy is efficacious and may stabilize hepatic function, our data suggest that DCV-based therapy can be safely used in LT recipients with advanced liver disease. Of the 19 SAE-related hospitalizations, 2 were possibly attributed to the antiviral treatment regimen and both resolved on continued therapy. The prespecified SAEs that we reported are similar to those reported in other prospective studies of direct-acting antiviral agents in LT recipients, including infections and progressive liver failure.12, 13, 27 However, we believe that our rate of AE reporting is likely underestimated because of the retrospective nature of our study. There were 6 patients who died while receiving DCV-based combination oral antiviral therapy (Table 4). Three patients, all with progressive allograft failure, died within the first month of therapy. Two of these patients had markedly elevated BL bilirubin levels consistent with severe cholestatic HCV infection, and 1 had grade 1-2 encephalopathy at the start of DCV-based therapy. The 3 patients who died of nonhepatic causes had evidence of virological suppression at their last available measurement. These observations suggest that potent antiviral regimens may rescue some but not all patients with allograft dysfunction due to HCV infection.17 Therefore, we feel it is quite reasonable to pursue all-oral antiviral therapy in these very ill patients in the hope of recovering their liver function.

DCV is a potent pangenotypic inhibitor of the NS5A replication complex.28, 29 However, NS5A resistance–associated variants emerge more frequently in patients with HCV genotype 1a infection treated with DCV than in patients with genotype 1b.30, 31 In addition, patients with HCV genotype 1a infection who harbor the Q80K variant are less likely to respond to the NS3 protease inhibitor SMV and more likely to develop virological failure.32 Interestingly, only 1 of the 5 patients in our series with virological breakthrough or relapse had HCV genotype 1a infection (Table 3). Although we did not have pretreatment serum available to test for NS5A or NS3A resistance–associated variants, all 5 patients with virological breakthrough or relapse remained clinically stable during a median posttherapy follow-up of 26 weeks. In fact, virological breakthrough patient 1 in Table 3 had an improvement in his serum alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels at 11 weeks after EOT. Nonetheless, our data and those of others suggest that DCV should preferentially be combined with SOF rather than SMV in LT recipients, particularly in those with advanced liver disease.33

DCV is an attractive agent to consider for use in LT recipients due to its pangenotypic activity, favorable side effect profile, and lack of interactions with immunosuppressive medications. Several studies have demonstrated promising efficacy data when DCV is combined with SOF in difficult-to-treat patients across multiple HCV genotypes, including HIV-coinfected patients and those with HCV genotype 3 infection.14, 15, 34, 35 Furthermore, the dose of DCV does not need to be reduced in patients with renal or hepatic impairment.36 Although DCV is a cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) substrate, its low binding affinity has not led to clinically significant drug-drug interactions with most other CYP3A4 substrates, including the calcineurin inhibitors or mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.37 In contrast, use of the ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitors paritaprevir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir has led to significant drug-drug interactions with the calcineurin inhibitors in LT recipients.38 SMV is metabolized in the liver and cleared by biliary excretion but is not a substrate for CYP3A4. However, SMV is a substrate for organic anion-transporting polypeptide B (OATPB), and it can have significant drug-drug interactions with other OATPB substrates, including cyclosporine.39 In reviewing our data set, only 1 of 4 patients who received SMV and DCV with concomitant cyclosporine experienced transient nephrotoxicity and anemia, both of which subsequently improved with RBV dose reduction. Nonetheless, it is important to recall that there is a warning from the manufacturer advising practitioners not to administer SMV to patients receiving cyclosporine.39

In summary, our study demonstrated that a 24-week course of DCV-based therapy in combination with SOF or SMV was highly efficacious in LT recipients with severe recurrent HCV infection, with EOT and SVR12 rates of 91% and 87%, respectively. All of our 31 patients with severe cholestatic HCV infection who completed therapy and follow-up had HCV RNA that was undetectable or <43 IU/mL at EOT and also achieved an SVR, which led to markedly improved short-term outcomes compared with those in historical controls treated with interferon.40-42 In addition to being well tolerated, DCV-based combination therapy will allow many LT recipients with contraindications to interferon to be safely and effectively treated. The strengths of our study include the enrollment of nearly 100 patients from multiple sites around the world, mostly with advanced liver disease, who all received a 24-week course of DCV-based therapy. Limitations of our study include the lack of centralized testing for resistance-associated variants in pretreatment and on-treatment samples and the variable use of RBV in the treated patients. A 12-week course of DCV-based antiviral therapy may be efficacious in some LT recipients, but further studies are needed.16

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that DCV-based therapy for 24 weeks was well tolerated and highly effective in LT recipients with advanced liver disease. This therapy may lead to stabilization or improvement in hepatic function and provide an effective rescue therapy even for LT recipients with severe cholestatic HCV.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge research assistance from the following individuals: Hatef Massoumi and Paul Gaglio, Department of Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Vincenzo Pisani, M.D., Unit of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Mater Domini Teaching Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy; Stefan Zeuzem, M.D., University Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany; Carmen Vinaixa, M.D., and Vanessa Hostangas, M.D., Politecnic University Hospital La Fe, Valencia, Spain; Pamela Durry, site coordinator at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI; Rafael Barcena, M.D., Ph.D., Liver Transplant Unit, Gastroenterology, Santos del Campo, Madrid, Spain; and Marcela Pezzoto Laurito, M.D., Claudia Musat, MD, Thresiamma Lukose, Pharm.D., Damaris Carriero, N.P., Karen Weisz, N.P., Elizabeth Verna, M.D., M.S., Lori Rosenthal Cogan, D.N.P., Patricia Harren, D.N.P., Grace Bayona, Melissa Buchan, Ryan Perdomo, and Idalia M. Fernandez-Sloves, Columbia University Medical Center. Medical writing assistance was provided by Kerry R. Garza, Ph.D., of MediTech Media, Ltd., and funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.