High risk of delisting or death in liver transplant candidates following infections: Results from the North American consortium for the study of end-stage liver disease

See Editorial on Page 866

Abstract

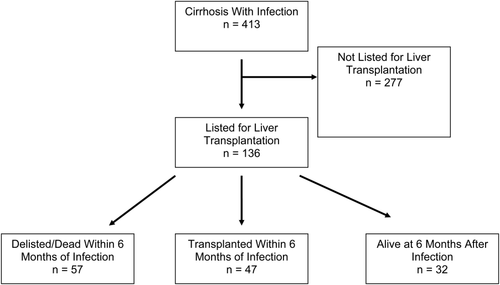

Because Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores at the time of liver transplantation (LT) increase nationwide, patients are at an increased risk for delisting by becoming too sick or dying while awaiting transplantation. We quantified the risk and defined the predictors of delisting or death in patients with cirrhosis hospitalized with an infection. North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) is a 15-center consortium of tertiary-care hepatology centers that prospectively enroll and collect data on infected patients with cirrhosis. Of the 413 patients evaluated, 136 were listed for LT. The listed patients' median age was 55.18 years, 58% were male, and 47% were hepatitis C virus infected, with a mean MELD score of 2303. At 6-month follow-up, 42% (57/136) of patients were delisted/died, 35% (47/136) underwent transplantation, and 24% (32/136) remained listed for transplant. The frequency and types of infection were similar among all 3 groups. MELD scores were highest in those who were delisted/died and were lowest in those remaining listed (25.07, 24.26, 17.59, respectively; P < 0.001). Those who were delisted or died, rather than those who underwent transplantation or were awaiting transplantation, had the highest proportion of 3 or 4 organ failures at hospitalization versus those transplanted or those continuing to await LT (38%, 11%, and 3%, respectively; P = 0.004). For those who were delisted or died, underwent transplantation, or were awaiting transplantation, organ failures were dominated by respiratory (41%, 17%, and 3%, respectively; P < 0.001) and circulatory failures (42%, 16%, and 3%, respectively; P < 0.001). LT-listed patients with end-stage liver disease and infection have a 42% risk of delisting/death within a 6-month period following an admission. The number of organ failures was highly predictive of the risk for delisting/death. Strategies focusing on prevention of infections and extrahepatic organ failure in listed patients with cirrhosis are required. Liver Transpl 21:881-888, 2015. © 2015 AASLD.

Abbreviations

-

- ACLF

-

- acute-on-chronic liver failure

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- ETOH

-

- alcohol-induced liver disease

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- I-ACLF

-

- infection-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure

-

- INR

-

- international normalized ratio

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MELD

-

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- NACSELD

-

- North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- REDCap

-

- Research Electronic Data Capture

-

- SBP

-

- spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- UNOS

-

- United Network for Organ Sharing

-

- UTI

-

- urinary tract infection

Liver transplantation (LT) is a lifesaving procedure for patients with hepatic synthetic dysfunction or primary hepatic malignancy.1 However, the increasing prevalence of advanced liver disease coupled with limited organ availability has resulted in an ever-increasing disparity between supply of and demand for donor liver allografts.2 Furthermore, advancing age, frailty, and increasing frequency of comorbidities in listed patients present dynamic challenges to ongoing candidacy.3-5 Even after a thorough evaluation for LT, 25% of listed patients now die or become too sick before a successful transplantation can be accomplished.6

Dysbiosis, frequent bacterial translocation, and immune deficiency, predispose patients with cirrhosis to infections and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), and 1 infection increases the risk of a second.7-15 The North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease (NACSELD) has reported on a spectrum of infections encountered in end-stage liver disease patients.16 The risk of these infectious complications and infection-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure (I-ACLF) has increased in potential transplant candidates.16 This can increase the risk of delisting and death. However, the precise role of different types of infections, different individual organ failures, and the number of organ failures, which temporally contribute to delisting and death in listed patients needs to be clarified. In addition, more information is needed on patient survival following transplantation in those with a recent infection or those with or without I-ACLF. To that end, we report the observations from a large prospective database that evaluated the reasons and predictors of delisting/death following an infection in patients listed for LT, and we subsequently assessed post-LT survival in these patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

NACSELD is composed of 15 centers in North America that prospectively enroll patients with cirrhosis who have infections. A full description of the cohort and all variables collected can be found in previous reports.12, 16, 17 In brief, all centers received institutional review board approval before prospective patient enrollment. Deidentified data were managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) at Virginia Commonwealth University. REDCap is a web-based application that allows data capture for research studies, providing (1) validated data entry; (2) audit trails; and (3) automated export procedures for statistical packages.

Sites acquired information about patient demographics, comorbid conditions, complications of cirrhosis, use of medications, and history of hospitalizations and antibiotic use in the previous 6 months. Other data recorded included hospital course, laboratory data, antibiotics given, in-hospital complications of cirrhosis, procedures performed during the hospitalization, and organ failure. They were defined as (1) hepatic encephalopathy, West Haven grade III or IV; (2) shock, (mean arterial pressure < 60 mm Hg or a reduction of 40 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure from baseline) despite adequate fluid resuscitation and cardiac output; (3) need for mechanical ventilation; and (4) need for renal replacement therapy.

The entire cohort included admitted patients with cirrhosis who have or develop 1 or more infections during hospitalization. This report focuses on the transplant outcomes of these patients. Patient survival and United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) listing status were assessed during the index admission and during the 6-month follow-up period. Standard laboratory tests were performed at each facility as part of the standard of care.

All data were collected prospectively and entered by the site's principal investigators and coordinators. The site's principal investigators were responsible for accuracy of data entry of the clinical variables. They were also responsible for auditing their site's data against the patients' medical records to ensure correct entry.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We compared demographics, severity of liver disease, medications, and infection-related variables between patients listed for LT and those not listed for LT. We further compared baseline laboratory characteristics, including Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), in patients who underwent LT, were delisted/died following an infection, and those continuing to wait for LT. Results are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) unless otherwise specified. When comparing groups, chi-square, Fisher's exact, Wilcoxon-rank, or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for categorical variables, whereas t tests and analysis of variance were used for continuous variables. The determinants of mortality were calculated using a logistic regression model. Univariate analysis was performed to determine predictors of delisting/death. The variables analyzed were age, sex, etiology of cirrhosis, creatinine, MELD score, sodium, use of collected medications, and the types of infection. We also examined the predictors of delisting and death in those who were listed for LT.

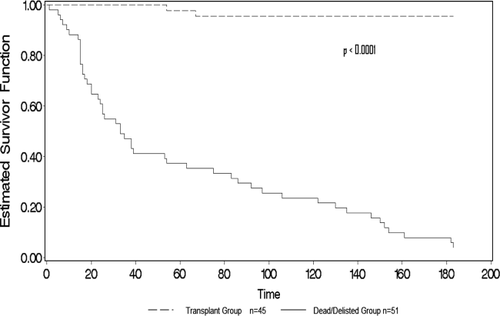

Lastly, we compared the survival of patients transplanted after an infection with the survival of those who continue to await transplantation or were delisted/died. For the logistic regression models, patients who died/delisted within 6 months of the index infection were compared to patients who underwent transplantation or were alive without transplant within 6 months of the index infection.

For the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis models, patient outcomes within the first 6 months of the index infection were compared in the following 2 groups: (1) those who died/delisted and (2) those who underwent transplantation.

RESULTS

A total of 413 infected patients with cirrhosis were prospectively enrolled in the study from December 2010 to December 2012, 136 of whom were listed for LT (Fig. 1). Of those listed, 42% (57) were delisted or died, 35% (47) underwent transplantation, and only 24% (32) achieved transplant-free survival 6 months after hospital admission for an infection. The index admission demographics and clinical characteristics of listed versus not listed patients are shown and compared between the 2 groups (Table 1). Listed patients more often had hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, less often alcohol-induced liver disease (ETOH), higher MELD scores (P < 0.001), higher total bilirubin levels (P < 0.001), and higher international normalized ratios (INRs; P < 0.001) than unlisted patients. Infection etiologies were similar between the groups with the notable exception of spontaneous bacteremia, which was more common in listed patients. Listed patients were also more frequently on spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) prophylaxis (P < 0.001), rifaximin (P < 0.001), and lactulose (P < 0.001) than patients with cirrhosis not listed for transplantation (Table 1).

| Overall population, n = 413 | Not Listed for LT, n = 277 | Listed for LT, n = 136 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 55.58 (9.47) | 55.78 (9.77) | 55.18 (8.83) | 0.82a |

| Sex, male, % | 58 | 59 | 57 | 0.76b |

| Diagnosis, % | 0.004 | |||

| HCV alone | 26 | 22 | 33 | |

| ETOH alone | 29 | 35 | 17 | |

| HCV and ETOH | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| NASH/cryptogenic cirrhosis | 17 | 15 | 21 | |

| Other | 13 | 12 | 15 | |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 6.19 (6.65) | 5.84 (6.81) | 6.89 (6.26) | <0.001a |

| INR, mean (SD) | 1.78 (0.67) | 1.69 (0.66) | 1.94 (0.66) | <0.001a |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 1.60 (1.15) | 1.55 (1.08) | 1.69 (1.28) | 0.23a |

| MELD, mean (SD) | 21.05 (7.89) | 20.08 (7.74) | 23.03 (7.84) | <0.001a |

| Albumin, g/dL, mean (SD) | 2.64 (0.77) | 2.66 (0.83) | 2.62 (0.65) | 0.86a |

| Sodium, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 131.72 (6.50) | 131.74 (6.63) | 131.69 (6.27) | 0.76a |

| Infections: initial admission, % | ||||

| SBP | 26 | 24 | 29 | 0.33b |

| Bacteremia | 16 | 11 | 24 | <0.001b |

| Respiratory | 10 | 10 | 11 | 0.69b |

| Skin | 12 | 14 | 9 | 0.15b |

| UTI | 26 | 27 | 25 | 0.71b |

| C. difficile | 5 | 5 | 4 | 0.78b |

| Medications: initial admission, % | ||||

| PPI | 58 | 58 | 59 | 0.82b |

| SBP prophylaxis | 18 | 12 | 29 | <0.001b |

| Beta-blocker | 42 | 40 | 44 | 0.43b |

| Rifaximin | 38 | 30 | 55 | <0.001b |

| Lactulose | 62 | 56 | 74 | 0.001b |

- a Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney U test).

- b Chi-square test, appropriate d.f.

When comparing infected patients who underwent LT to those who died or were delisted and to those still awaiting LT at 6 months after infection, patients who underwent transplantation had higher bilirubin (P < 0.001) but a lower creatinine (P = 0.005) than those who were delisted/died. The mean MELD score was similar between those transplanted and those who died/delisted, but it was markedly lower among those who achieved transplant-free survival (P < 0.001). The only significant difference in type of infection between the groups was a lower prevalence of urinary tract infection (UTI) in those who were delisted/died compared to the other 2 groups (Table 2).

| Transplanted, n = 47 | Delisted/Dead, n = 57 | Awaiting Transplantation, n = 32 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD) | 8.76 (7.29) | 7.01 (5.83) | 3.93 (4.01) | <0.001a |

| INR, mean (SD) | 1.96 (0.76) | 2.09 (0.64) | 1.65 (0.39) | 0.003a |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 1.65 (1.05) | 2.00 (1.58) | 1.21 (0.74) | 0.005a |

| MELD, mean (SD) | 24.26 (7.25) | 25.07 (8.00) | 17.59 (5.82) | <0.001a |

| Albumin, mean (SD) | 2.65 (0.69) | 2.58 (0.66) | 2.64 (0.61) | 0.62a |

| Sodium, mean (SD) | 130.66 (6.74) | 131.42 (6.54) | 133.69 (4.52) | 0.07a |

| Infections: initial admission, % | ||||

| SBP | 36 | 26 | 22 | 0.34b |

| Bacteremia | 21 | 26 | 25 | 0.83b |

| Respiratory | 9 | 14 | 9 | 0.63b |

| Skin | 4 | 11 | 13 | 0.38b |

| UTI | 40 | 14 | 22 | 0.008b |

| C. difficile | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0.18b |

| Median time from infection to transplantation/death/delisting (Interquartile Range) | 30.00 (16.00, 70.00) | 33.00 (16.00, 106.00) | — | — |

- a Kruskal-Wallis test

- b Chi-square test, appropriate degrees of freedom.

When focusing on the 42% of patients who were delisted/died within 6 months of infection, the number of organ failures at index hospitalization was highest in this group (19% had 3 and 19% had 4 individual organ failures, (Table 3)). Patients who underwent transplantation had fewer organ failures compared to those who were delisted and/or died. In fact, at least 3 organ failures occurred in 9% of those transplanted, 19% of those who died/delisted, but in only 3% of those who achieved transplant-free 6-month survival (P = 0.004). Twenty percent had both respiratory and brain failure, whereas the other 80% had one or the other or none. In those who had both, brain failure preceded intubation for respiratory failure and, thus, was not confounded by sedation provided for intubation (data not shown).

| Transplanted, n = 47 | Delisted/Dead, n = 57 | Awaiting Transplantation, n = 32 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure, % | 17 | 41 | 3 | <0.001a |

| Circulatory failure, % | 16 | 42 | 3 | <0.001a |

| Renal failure, % | 37 | 43 | 30 | 0.50a |

| Brain failure, % | 55 | 79 | 47 | 0.005a |

| Number of organ failures, median (IQR) | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 1.00 (0.00–1.00) | <0.001b |

| Number of organ failures, % | 0.004a | |||

| 0 | 28 | 16 | 44 | |

| 1 | 38 | 26 | 34 | |

| 2 | 21 | 19 | 19 | |

| 3 | 9 | 19 | 3 | |

| 4 | 4 | 19 | 0 |

- a Chi-square test, appropriate d.f.

- b Kruskal-Wallis test.

In univariate analysis to predict death or delisting, the number of organ failures was the single factor with greatest predictive power (odds ratio [OR] = 1.89; P < 0.001; Table 4). When analyzing each organ system failure separately, circulatory (OR = 6.11; P < 0.001), respiratory (OR = 5.26; P < 0.001), and brain (OR = 3.40; P = 0.002) failures were predictive of delisting/death whereas renal failure was not statistically significant (OR = 1.44; P = 0.31).

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald χ2 | P Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ failures | |||||

| Number of organ failures | 0.64 | 0.16 | 16.31 | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.39–2.58) |

| Circulatory failure | 1.81 | 0.46 | 15.27 | <0.001 | 6.11 (2.47–15.14) |

| Respiratory failure | 1.66 | 0.45 | 13.82 | <0.001 | 5.26 (2.13–12.64) |

| Brain failure | 1.22 | 0.40 | 9.55 | 0.002 | 3.40 (1.56–7.38) |

| Renal failure | 0.37 | 0.36 | 1.02 | 0.31 | 1.44 (0.71–2.94) |

| Demographics and laboratory values | |||||

| MELD | 0.06 | 0.02 | 6.42 | 0.01 | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) |

| Creatinine | 0.35 | 0.16 | 5.08 | 0.02 | 1.42 (1.05–1.92) |

| INR | 0.62 | 0.29 | 4.63 | 0.03 | 1.86 (1.06–3.26) |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.02 | 3.02 | 0.08 | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) |

| Sex, male | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.42 | 1.33 (0.67–2.66) |

| Albumin | –0.15 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.87 (0.51–1.47) |

| Total bilirubin | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 1.01 (0.95–1.06) |

| Alcoholic etiology | 0.08 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 1.08 (0.44–2.67) |

| Sodium | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

| Type of infection | |||||

| UTI | –1.10 | 0.45 | 5.97 | 0.02 | 0.33 (0.14–0.80) |

| Respiratory | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 1.68 (0.57–4.93) |

| Skin | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 1.43 (0.44–4.69) |

| SBP | –0.20 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.82 (0.38–1.75) |

| Bacteremia | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 1.21 (0.55–2.67) |

| C. difficile | –0.38 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.68 (0.12–3.86) |

In univariate analysis of laboratory factors, MELD score (OR per point increase = 1.06, P = 0.01), serum creatinine (OR = 1.42; P = 0.02), and INR (OR = 1.86; P = 0.03) were predictive of delisting/death. There were no specific demographic features associated with delisting (Table 4), although UTIs were associated with a lower risk of delisting/death than other types of infections (OR = 0.333; P = 0.02).

Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine predictors of delisting/death. When compared to all other types of infections for which patients were admitted, UTIs were consistently associated with a lower risk of delisting/death. In contrast, an increasing number of organ failures was associated with an increased risk of delisting/death, particularly respiratory failure and brain failure (Table 5). Of the 45 patients transplanted (of 47) with survival information, 39 had 0 to 2 organ failures and 6 had 3 to 4 organ failures. In the 0 to 2 failure group only 2 died, and in the 3 to 4 failure group, none died (P > 0.99). Survival following transplant was statistically higher compared with those delisted/dead (P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald χ2 | P Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of organ failures | |||||

| UTI | –1.41 | 0.50 | 8.04 | 0.005 | 0.24 (0.09, 0.65) |

| Number of organ failures | 0.71 | 0.17 | 17.82 | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.46, 2.84) |

| Individual system failures | |||||

| UTI | –1.14 | 0.50 | 5.24 | 0.02 | 0.32 (0.12, 0.85) |

| Respiratory failure | 1.52 | 0.47 | 10.29 | 0.001 | 4.58 (1.81, 11.59) |

| Brain failure | 1.01 | 0.43 | 5.62 | 0.02 | 2.76 (1.19, 6.37) |

DISCUSSION

This study documents that hospitalized infected patients with cirrhosis with extrahepatic organ failure are at higher risk of delisting or death before LT. The risk of being delisted within 6 months is much higher in infected patients with cirrhosis (42%) than in uninfected wait-listed patients (data not shown). A 2006 publication from UNOS data documented 16.9% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were delisted within 6 months, whereas patients listed for nonmalignant indications had a lower 6-month delisting rate (13.5%).18 Specifically in this group, higher MELD scores, age, and metabolic disease diagnoses had a higher risk of delisting.18 Our data noted a 42% delisting rate within 6 months of an infection in listed candidates, indicating that infection-related multiorgan failure is a leading cause of delisting.

It is not surprising that patients listed for LT had higher MELD scores and a lower prevalence of alcohol-induced cirrhosis than patients who were not listed. Listed candidates were also more likely to be on SBP prophylaxis and rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy treatment. They had higher rates of bacteremia in comparison to those not on the list, which is again reflective of their greater liver disease severity. However, we cannot rule out that the higher rate of rifaximin and SBP prophylaxis use in listed patients does not simply reflect closer follow-up or a difference in socioeconomic status. Though the rates of bacteremia were different, there were no differences in the frequency of other types of infections among the overall population, those listed, and those not listed for LT (Table 1).

In general, the reasons for removing patients from the LT wait list are heterogeneous.18, 19 Patients may be delisted for well-defined considerations such as exceeding HCC criteria, or for less well-defined criteria such as advancing age, severe deconditioning, noncompliance, psychosocial issues, or multiple comorbidities.18, 19 Practical considerations for delisting also include failure of the “eye-ball” test. Thus, patients are prioritized for LT on an objective basis (MELD score), but they are delisted largely on a subjective basis. We did not set up an a priori uniform delisting criterion; therefore, delisting would be categorized as subjective and at the discretion of individual investigators/transplant programs and likely subject to variability. Therefore, outlining objective criteria for delisting would advance clinical practice.

This is arguably the first article that has assessed the impact of infections on delisting/death in patients who were initially considered candidates for LT. Such data are not available in the UNOS database or Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients. In the infected population with cirrhosis, it is evident that multiple organ failure accounts for a substantial proportion of delisted patients/deaths. Although patients with up to 2 organ failures were still deemed acceptable candidates for transplantation, more than 2 organ failures was a predictor of delisting/death (Table 4). The NACSELD has termed this entity I-ACLF,16 which is associated with high 30-day mortality. The current observations extend those findings into transplantation. Although the overall mortality following I-ACLF was high with even 2 organ failures,6 it did not deter transplant programs in our study from transplanting these patients. However, patients with 3 or 4 organ failures were most often considered “too sick” for LT. We can infer from these results that up to 2 organ failures is usually not a reason to delist patients, whereas objective demonstration of 3 or more extrahepatic organ failures could be considered more challenging from a transplant perspective. Further studies are needed to evaluate not only the survival but the cost-effectiveness of transplanting patients with varying numbers of organ failures.

In the UNOS database, patients are delisted for “other” or being “too sick to transplant.” On the basis of an assessment from 4 transplant centers, the rate of delisting for reasons coded as clinical deterioration, “other” reasons, and “miscellaneous” causes has ranged from 4.4% to 19.9%.20, 21 It is conceivable that some of these represent infection-related morbidity that led to delisting. As we move forward, it will be important to better characterize these patients to have an accurate estimate of infection-related reasons for delisting.

In our study, univariate analysis showed that with the exception of UTI where patients were less likely to die, the type of infection did not predict delisting/death (Table 4). The relatively lower impact of UTI on delisting is interesting because it is one of the most common infections in cirrhosis. This phenomenon may be partly related to the transplant team's attitudes toward UTIs compared to other infections, presumed to either be more dangerous peritransplant (eg, pneumonia) or directly related to cirrhosis (eg, SBP). However, further research is needed to discern if UTIs have any negative impact peritransplant.

Interestingly, MELD scores did not differentiate between those who were ultimately transplanted versus those who were delisted (Table 4). This indicates that factors not measured in the MELD score are critical factors in determining the risk of delisting and death. As expected, those who survived and continued to await transplant had a lower MELD score compared to those who either received a transplant or died/delisted while waiting (Table 2). Although the number of organ failures is a likely contributor to who is delisted and dies, a more detailed understanding of the factors being used by clinicians to determine suitability for transplant needs to be collected, analyzed, and standardized.

Despite infection-related organ failures during the index admission, 33% of listed patients successfully underwent a transplant within a 6-month period (data not shown). Importantly, the survival of these patients in the 6-month posttransplant period was significantly better compared to those who were delisted or not transplanted after infection (Figure 2). Predictors of delisting/death were more than 2 organ failures. Univariate analysis indicated that organ failures leading to delisting/death were dominated by respiratory, circulatory, and brain failures (Table 5). It could be argued that an overlap existed between respiratory failure and hepatic encephalopathy (because of the use of sedation in intubated patients) (Table 4). However, ventilation and hepatic encephalopathy were both independently associated with poor outcomes, with ventilator failure being less frequent than hepatic encephalopathy. Notably, dialysis-requiring renal failure was not an independent predictor of delisting/death. Perhaps it was thought that transplanted patients had the potential for renal recovery, or they could simultaneously or subsequently undergo renal transplantation. Also the higher weight assigned for dialysis dependence in the MELD scoring system could have provided an advantage leading to earlier transplantation.

We acknowledge some of the limitations of the study in that we have not evaluated reasons for nonlisting some of the patients with advanced liver disease, the impact of norfloxacin primary prophylaxis in preventing infections in those particularly listed for LT, and any regional variation in rates of listing and delisting.

In summary, transplantation was performed with good outcomes in this selected multicenter large cohort of infected patients with cirrhosis after hospitalization. Respiratory failure and brain failure were independent predictors of delisting, whereas dialysis-dependent renal failure did not deter centers from proceeding with LT. Although survival in the cohort of infected patients who underwent LT was good, this study has not assessed the resource utilization impact in the pretransplant and posttransplant periods. Factors such as length of hospital stay, need for long-term dialysis, and other associated costs (among other factors) need to be systematically analyzed in prospective studies. Also, it is unclear what outcomes might be for patients transplanted with more than 2 organ failures. Importantly, this study shows that infections can rapidly change a patient's suitability for transplant; therefore, prevention of infections and subsequent organ failure is critical.