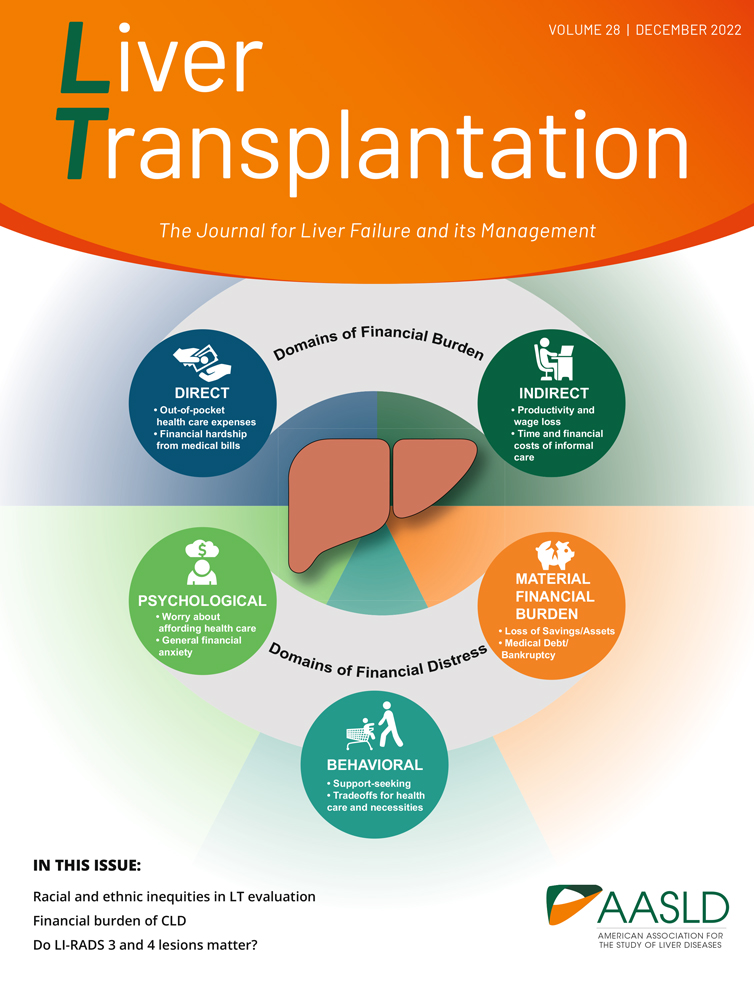

Liver transplantation cost in the model for end-stage liver disease era: Looking beyond the transplant admission†‡§¶

See Editorial on Page 1159

The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

This study is based on Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data as of August 6, 2007.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network or the US Government.

Abstract

We examined the relationship between the total cost incurred by liver transplantation (LT) recipients and their Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score at the time of transplant. We used a novel database linking billing claims from a large private payer with the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network registry. Included were adults who underwent LT from March 2002 through August 2007 (n = 990). Claims within the year preceding and following transplantation were analyzed according to the recipient's calculated MELD score. Cost was the primary endpoint and was assessed by the length of stay and charges. Transplant admission charges represented approximately 50% of the total cost of LT. MELD was a significant cost driver for pretransplant, transplant, and total charges. A MELD score of 28 to 40 was associated with additional charges of $349,213 (P < 0.05) in comparison with a score of 15 to 20. Pretransplant and transplant admission charges were higher by $152,819 (P < 0.05) and $64,286 (P < 0.05), respectively, in this higher MELD group. No differences by MELD score were found for posttransplant charges. Those in the highest MELD group also experienced longer hospital stays both in the pretransplant period and at the time of LT but did not have higher rates of re-admissions. In conclusion, high-MELD patients incur significantly higher costs prior to and at the time of LT. Following LT, the MELD score is not a significant predictor of cost or re-admission. Liver Transpl 15:1270–1277, 2009. © 2009 AASLD.

Publications describing the economics of liver transplantation (LT) date back to the 1980s.1-4 In the pre–Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) era, there was a perception that the cost of LT was decreasing as a result of a shorter length of stay (LOS) and improved techniques.5, 6 Subsequent changes in organ allocation to prioritized sicker receipts, such as the United Network for Organ Sharing Status 2b system, led to concerns regarding resource utilization for this population.4

The implementation of the MELD score has shifted priority to the sickest patients, with a subsequent reduction in waiting list mortality.7, 8 Consequently, the complexity of patients receiving LT has increased dramatically, imposing financial pressure on transplant centers due to a significant spike in resource utilization.9, 10

Axelrod et al.9 initially described the increase in resource utilization in the MELD era and its impact on transplant center finances. Subsequently, Washburn et al.10 linked the MELD score of the patient with the cost of the transplant admission. These studies have been limited to single-center financial information regarding the initial transplant admission to estimate the cost of LT. However, an assessment of the total economic burden of LT should also include evaluation, maintenance on the waiting list, pretransplant admissions, management of complications, and long-term follow-up. Utilization of a novel, national, multicenter private-payer database allowed us to examine the cost of LT beyond the initial transplant admission.

This study sought to assess the impact of the MELD system on the total cost of LT, to verify the association of the MELD score with pretransplant costs, and to determine if the economic severity of liver disease persists after a successful transplant.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; DRI, donor risk index; DRG, diagnosis-related group; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICD-9, International Code of Diagnosis 9; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; LOS, length of stay; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; SD, standard deviation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Protocol, Design, Data Sources, and Inclusion Criteria

This project was approved by the institutional review board of Saint Louis University. A retrospective cohort study was initially conducted, including data from all LT recipients who were wait-listed from January 1, 1987 through August 6, 2007. Data were drawn from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) research files and supplemented with clinical claim data from a large private insurance company's database. The OPTN data system includes data submitted by the members of the OPTN on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States and has been described elsewhere. The Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight for the activities of the OPTN contractor. A subsidiary of the private insurance company created the link between the databases using coded OPTN linking variables. The linkage was made on the basis of the patient's name, Social Security number, date of birth, and gender. All direct identifiers were removed before the final data set was sent for analysis.

For the present study, inclusion was restricted to adult patients (≥18 years of age) who received their liver allografts for chronic liver disease from March 1, 2002 through August 6, 2007 and who had the insurance company as the primary payer with continuous enrollment during at least 1 of the time periods of interest. Patients with liver-kidney transplants were included, whereas all other multiple organ transplants were excluded.

Ascertainment of Claims and Charges

The insurance database contains all medical and pharmacy claims submitted for the beneficiaries. The individual claim records contained the date on which the claim was paid, the date on which the services were performed, the diagnostic and procedure codes, the place of service codes, the revenue codes, and the amount charged. We selected all claims that fell within a subject's coverage during his or her eligibility period. Because insurance coverage can change, the patient populations included within a given period of analysis may differ; however, all patients with complete data for that entire phase of assessment were examined. Because of the frequency of distribution of the claims, we then limited the claims from 1 year prior to the OPTN-supplied transplant date through 1 year post-transplantation.

We then divided the claims into 1 of 3 periods: the pretransplant period, the transplant period, and the posttransplant period. The pretransplant period included claims that fell from 365 days before transplantation to 3 days prior to the transplant date. The transplant period contained claims that fell from 2 days prior to the transplant through 90 days post-transplant. The posttransplant period had claims from 91 to 365 days post-transplant.

Charges for claims with a date of service that occurred after a date of death were set to zero. The few claims that were clearly related to organ acquisition, as indicated by revenue codes (n = 47), were excluded from the study as this cost had not been billed consistently within the insurance company's system. We aggregated charges per subjects within the 3 transplant periods as well as the total charges for the entire study duration.

Subjects were included in the pretransplant, transplant, or posttransplant analysis if they were eligible for insurance coverage during the entirety of the corresponding transplant period. In addition to insurance eligibility, subjects within the transplant period were also required to have a revenue code for an intensive care unit (ICU) stay and a diagnosis-related group (DRG) code for LT or an International Code of Diagnosis 9 (ICD-9) code (see the appendix) for LT along with any DRG. To be included in the analysis for total cost, subjects had to have continuous enrollment with the insurance carrier from day 365 pre-transplant to day 365 post-transplant. Extreme outliers were defined after a visual inspection of the distribution of the charges and defined to be those within the transplant analysis group with less than $50,000 or more than $2,000,000 in charges, and they were excluded from all analysis. These patients were excluded under the assumption that the insurance company was not their primary payer as the charges were too low for a transplant hospitalization (n = 53) or because they could potentially be medically different from the remaining population as their charges were much higher than those of the remaining study population (n = 2).

MELD, Donor Risk Index (DRI), and LOS

DRI was computed according to the formula defined by Feng et al.11 We categorized DRI as follows: 0 to 0.99, 1 to 1.49, 1.5 to 1.99, 2.0 to 2.49, and greater than 2.49. To calculate the LOS for the transplant hospitalization, we selected all inpatient claims on the basis of the place of service code, revenue code, procedure codes, and claim service dates that spanned more than 1 calendar day. If 1 of these 4 variables indicated that the claim was for an inpatient service, then it was considered in the LOS calculation. LOS calculation began on the initial date of the claim that enveloped the OPTN transplant date. LOS finished with the end date on this claim or with the end date of any subsequent inpatient claim when the initial date of the subsequent claim was equal to or earlier than the end date of the previous claim included in the LOS calculation. The LOS was then calculated to be the end date of the final claim in the series minus the initial date of the first claim that included the transplant date.

Clinical Outcome and Covariate Definitions

The primary outcome was cost. We used transplant charges (in dollars) and LOS as markers of cost. Charges were those independently generated by each patient during the respective transplant period (the pretransplant, transplant, or posttransplant period). For the purpose of the current analysis, cost and charges are used indistinctively. Total cost was calculated as the sum of pretransplant, transplant, and posttransplant charges. Direct comparisons were made among recipients of LT according to their MELD score group at transplantation.

Covariates included gender, age, race, ethnicity, blood type, college education, employment status, primary OPTN cause of liver failure [hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or other cause], region, retransplantation, split grafts, deceased donor recipient, kidney cotransplantation, DRI, and body mass index (BMI). The pretransplant characteristics were defined by ICD-9, revenue, and DRG codes (see the appendix) and consisted of hospital-bound (in the hospital more than 2 days prior to the transplant date), ICU-bound, mechanical ventilation, ascites/spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatic encephalopathy. We used the definition of allograft loss and patient death from the OPTN registry.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square analysis to examine the demographics of the subjects by MELD group for the total sample. We examined unadjusted patient costs by MELD for each period using the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum. We then performed multivariate regression analysis to determine the cost drivers for each period and total charges. For this analysis, we adjusted for MELD, gender, age, primary OPTN cause of liver failure, retransplantation, region, liver-kidney transplant, split graft, blood type, and DRI. The frequency and length of LOS, hospitalizations, and ICU LOS by MELD were calculated for each of the 3 periods and compared with chi-square and analysis of variance methods. Kaplan-Meier curves were drawn, depicting the patient and graft survival differences of patients by MELD group. The log-rank test was used to determine if there was a significant difference in the curves. Missing data for the examined characteristics were categorized as other or unknown or were excluded from the analysis; this depended on the frequency of missing data for the given characteristic. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all significance tests. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

During the period of the study, we identified 3315 patients of the private insurance company with an OPTN LT record. Of those, 2738 patients were adults who received a primary liver or liver-kidney transplant. After excluding the 1748 patients who did not have continuous enrollment with the insurance carrier during any of the study windows, we were left with 990 subjects who met the eligibility criteria for the study, including 778 patients with claims during the pretransplant period, 690 patients with claims for the transplant period, and 678 transplant recipients with posttransplant claims. Among all subjects, 365 had complete claims in all 3 periods of the study.

The demographics of the population included in the study differed by the MELD category (Table 1). Patients with lower MELD scores (<20) were more likely to be 55 to 64 years old and non–African American, have a college degree, be employed, receive a split graft, receive a living donor transplant, and/or be diagnosed with HCC, HCV, or other causes of liver failure in comparison with those patients within the highest MELD category (P < 0.05 for all comparisons). Patients with higher MELD scores were more likely to have received a liver-kidney transplant, be in the ICU at the time of transplant, have decompensated liver disease (ascites and hepatic encephalopathy), be on mechanical ventilation, and/or have a higher BMI than those with lower MELD scores of 6 to 14 (P < 0.05 for all comparisons). The distribution of transplanted patients by MELD group is constant throughout most regions, with all but 2 being evenly distributed. Regions 4 and 5 have uneven distributions (P < 0.05 for both comparisons).

| MELD Score [n (%)] | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–14 (n = 285) | 15–20 (n = 296) | 21–27 (n = 216) | 28–40 (n = 193) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 76 (27.9) | 83 (30.5) | 65 (23.9) | 48 (17.7) | 0.67 |

| Male | 209 (29.1) | 213 (29.7) | 151 (21.0) | 145 (20.2) | |

| Age of recipients (years) | |||||

| 18–24 | 5 (29.1) | 10 (37.0) | 4 (14.8) | 8 (29.6) | 0.31 |

| 25–34 | 13 (31.7) | 10 (24.4) | 5 (12.2) | 13 (31.7) | 0.13 |

| 35–44 | 25 (18.5) | 44 (32.6) | 33 (24.4) | 33 (24.4) | 0.04 |

| 45–54 | 126 (28.5) | 135 (30.5) | 95 (21.5) | 86 (19.5) | 0.98 |

| 55–64 | 105 (34.1) | 87 (28.3) | 70 (22.7) | 46 (14.9) | 0.02 |

| 65+ | 11 (29.7) | 10 (27.0) | 9 (24.3) | 7 (18.9) | 0.97 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 229 (28.5) | 257 (32.0) | 174 (21.6) | 144 (17.9) | 0.008 |

| Black | 14 (18.2) | 25 (32.5) | 18 (23.4) | 20 (26.0) | 0.15 |

| Other | 42 (38.5) | 14 (12.8) | 24 (22.0) | 29 (26.6) | 0.0003 |

| Hispanic | 20 (30.8) | 9 (13.9) | 19 (29.2) | 17 (26.2) | 0.02 |

| College degree | 120 (30.5) | 100 (25.4) | 99 (25.1) | 75 (19.0) | 0.04 |

| Employment | 67 (37.4) | 65 (36.3) | 35 (19.6) | 12 (6.7) | <0.0001 |

| Blood type | |||||

| A | 110 (27.1) | 121 (29.8) | 96 (23.7) | 79 (19.5) | 0.63 |

| B | 37 (30.1) | 37 (30.1) | 25 (20.3) | 24 (19.5) | 0.97 |

| AB | 17 (38.6) | 11 (25.0) | 11 (25.0) | 5 (11.4) | 0.30 |

| O | 121 (29.0) | 127 (30.5) | 84 (20.1) | 85 (20.4) | 0.73 |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| HCC | 71 (67.6) | 21 (20.0) | 7 (6.7) | 6 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

| HBV | 9 (33.3) | 8 (29.6) | 2 (7.4) | 9 (29.6) | 0.23 |

| HCV | 99 (29.0) | 124 (36.3) | 70 (20.5) | 49 (14.3) | 0.002 |

| Other | 105 (30.5) | 143 (27.9) | 136 (26.5) | 129 (25.2) | <0.0001 |

| Missing | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0.56 |

| Region | |||||

| 1 | 5 (45.5) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (27.3) | 0.35 |

| 2 | 11 (25.0) | 14 (31.8) | 11 (25.0) | 8 (18.2) | 0.91 |

| 3 | 68 (29.7) | 70 (30.6) | 54 (23.6) | 37 (16.2) | 0.52 |

| 4 | 37 (22.6) | 71 (43.3) | 31 (18.9) | 25 (15.2) | 0.0007 |

| 5 | 27 (35.5) | 11 (14.5) | 15 (19.7) | 23 (30.3) | 0.005 |

| 6 | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 1.00 |

| 7 | 36 (25.9) | 33 (23.7) | 34 (24.5) | 36 (25.9) | 0.09 |

| 8 | 31 (26.5) | 32 (27.4) | 26 (22.2) | 28 (23.9) | 0.60 |

| 9 | 16 (40.0) | 8 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 8 (20.0) | 0.35 |

| 10 | 32 (31.1) | 32 (31.1) | 22 (21.4) | 17 (16.5) | 0.85 |

| 11 | 20 (32.8) | 22 (36.1) | 12 (19.7) | 7 (11.5) | 0.32 |

| Type of graft | |||||

| Retransplant | 2 (18.2) | 1 (9.1) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (36.4) | 0.16 |

| Split graft | 34 (46.6) | 22 (30.1) | 12 (16.4) | 5 (6.9) | 0.001 |

| Deceased donor | 253 (27.1) | 278 (29.8) | 210 (22.5) | 192 (20.6) | <0.0001 |

| Living donor | 32 (56.1) | 18 (31.6) | 6 (10.5) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Liver-kidney | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.9) | 20 (47.6) | 17 (40.5) | <0.0001 |

| Pretransplant characteristics | |||||

| Hospital-bound | 39 (14.2) | 48 (17.5) | 74 (26.9) | 114 (41.5) | <0.0001 |

| ICU-bound | 77 (21.7) | 88 (24.8) | 85 (23.9) | 105 (29.6) | <0.0001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (5.6) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (22.2) | 8 (44.4) | 0.02 |

| Dialysis | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4.0) | 20 (26.3) | 52 (68.4) | <0.0001 |

| Ascites/SBP | 107 (19.3) | 161 (29.0) | 155 (27.9) | 132 (23.8) | <0.0001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 49 (14.5) | 85 (25.1) | 105 (31.0) | 100 (29.5) | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) [mean (SD)] | 27.1 (5.2) | 28.4 (5.2) | 28.5 (5.7) | 28.8 (5.5) | 0.003 |

| DRI [mean (SD)] | 1.43 (0.42) | 1.38 (0.36) | 1.38 (0.39) | 1.37 (0.35) | 0.34 |

| MELD [mean (SD)] | 10.5 (2.5) | 17.4 (1.6) | 23.4 (2.1) | 34.1 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DRI, donor risk index; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ICU, intensive care unit; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; SD, standard deviation.

Association of the LT Charges and MELD Score

The correlation between the severity of illness as assessed by the transplant MELD score and unadjusted analysis of LT charges varied according to the transplant period (Table 2). The pretransplant charges and total charges for 1 year pre-transplant to 1 year post-transplant varied by MELD group (P < 0.0001 for both comparisons), but transplant admission charges and the posttransplant charges did not vary significantly by MELD group (P = 0.17 and P = 0.60, respectively).

| Charge | MELD Score | P Value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–14 | 15–20 | 21–27 | 28–40 | ||

| Total | 414.6 (300.7) | 465.1 (277.9) | 601.7 (547.1) | 738.6 (400.8) | <0.0001 |

| Pretransplant period | 77.1 (86.8) | 92.4 (110.5) | 158.3 (262.3) | 237.3 (229.8) | <0.0001 |

| Transplant admission period | 276.2 (197.4) | 298.7 (209.8) | 314.4 (240.1) | 332.2 (238.5) | 0.17 |

| Posttransplant period | 71.3 (127.4) | 63.9 (96.0) | 90.0 (190.1) | 88.9 (162.9) | 0.60 |

- NOTE: Charges are listed in thousands of US dollars [mean (standard deviation)].

- Abbreviation: MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

- * The data depict the mean charges for each transplant period. However, statistical comparisons were made with the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum P value of the logarithm of charges to account for distribution bias.

MELD Score as a Significant Driver of Transplant Charges

After adjustments for possible confounding factors (Table 3), patients in the highest MELD category (28-40) were found to have significantly higher charges compared to recipients with the lowest MELD scores (6-14) for total, pretransplant, and transplant admission charges (P < 0.05 for all comparisons). Being in the highest MELD group added an average of $333,300 to the total charge in comparison with being in this lower MELD group. Most of this additional cost was incurred in the pretransplant period. High-MELD patients had charges that were $145,500 greater on average than those in the lower MELD group. Charges for patients in the group with MELD scores of 6 to 14 were also significantly lower than the charges for those with MELD scores of 21 to 27 during the pretransplant period and overall (P < 0.05 for both comparisons). There was no difference in posttransplant charges by MELD group. MELD, liver-kidney transplants, and gender were the significant predictors of total cost in the multivariate analysis.

| Total | Pretransplant period | Transplant period | Posttransplant period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base cost | 452.6 (305.2 to 599.8)* | 85.2 (36.1 to 134.3)* | 274.0 (212.1 to 335.9)* | 69.5 (26.3 to 112.7)* |

| Female | 100.7 (12.3 to 189.1)* | 25.8 (−4.6 to 56.1) | 44.6 (6.2 to 83.0)* | −6.6 (−32.5 to 19.3) |

| MELD | ||||

| 6–14 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 15–20 | 72.7 (−33.5 to 178.9) | 10.7 (−24.9 to 46.3) | 30.5 (−15.1 to 76.0) | 0.5 (−30.7 to 31.7) |

| 21–27 | 177.4 (63.2 to 291.6)* | 62.0 (23.4 to 100.6)* | 34.5 (−15.1 to 84.7) | 27.8 (−6.5 to 62.1) |

| 28–40 | 333.3 (205.3 to 461.3)* | 145.5 (104.0 to 187.1)* | 60.7 (8.1 to 113.3)* | 25.6 (−11.4 to 62.6) |

| Liver-kidney | 212.3 (26.0 to 398.5)* | 178.3 (114.8 to 241.7)* | 90.9 (7.0 to 174.8)* | 2.6 (−55.1 to 60.3) |

- NOTE: Adjustments were made for the following nonsignificant variables: age, diagnosis (hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and other), donor risk index, previous transplant, recipient blood type, partial/split transplantation, and region. Costs are listed in thousands of US dollars [coefficient estimate (95% confidence interval)].

- Abbreviation: MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

- * P < 0.05.

For pretransplant charges, only MELD and liver-kidney transplants were significant predictors. MELD, gender, and liver-kidney transplants were the cost drivers of the initial transplant admission. There are no significant predictors of posttransplant charges in our model. The MELD score did not predict cost beyond the transplant admissions. Other factors that were examined and determined not to be significant cost drivers for any transplant phase included age, diagnosis, previous transplants, DRI, partial/split livers, and recipient blood type.

Association Between the MELD Score, LOS, and Outcomes

Both graft survival (Fig. 1A) and patient survival (Fig. 1B) varied by MELD group (P = 0.0005 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Subjects in the highest MELD group had an 8% decrease in both patient and graft survival rates in comparison with those in the remaining MELD groups at 2 years post-transplant.

(A) Graft and (B) patient survival according to the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) group (n = 990).

LOS for hospitalizations by MELD group is displayed in Table 4. Patients in the highest MELD group were more frequently in the ICU pre-transplant (52% versus 26.5-39.3%, P < 0.0001) and had longer ICU stays than those in lower MELD groups (P = 0.008). The ICU LOS during the initial transplant admission was also longer for those in the highest MELD group compared to the other MELD groups (P = 0.0004). Patients in the highest MELD group had longer total hospital stays during the transplant period than those in the lower MELD groups (P = 0.0009). During the posttransplant period, the rates of re-admission to both the hospital and the ICU did not vary by MELD group. However, those in the highest MELD group tended to stay in the ICU about twice as long as those in the lower MELD groups if they were re-admitted to the ICU (P = 0.006).

| MELD Score | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–14 | 15–20 | 21–27 | 28–40 | ||

| Admission pretransplant LOS | 1.8 (2.3) | 1.7 (1.9) | 2.0 (3.1) | 1.9 (2.4) | 0.64 |

| ICU pretransplant stay† | 1.4 (5.8) | 1.6 (3.5) | 2.1 (5.2) | 3.1 (4.9) | 0.008 |

| Pretransplant LOS* | 3.6 (10.7) | 3.8 (9.9) | 6.5 (12.7) | 8.2 (11.3) | 0.0001 |

| Total initial transplant stay | 17.7 (20.3) | 18.4 (18.3) | 21.2 (27.9) | 25.2 (21.0) | 0.009 |

| ICU transplant stay† | 3.7 (6.2) | 4.6 (11.6) | 7.4 (16.9) | 9.4 (18.4) | 0.0004 |

| Re-admission posttransplant LOS | 4.5 (12.6) | 4.3 (10.5) | 3.5 (7.9) | 4.7 (7.6) | 0.78 |

| ICU posttransplant stay† | 2.9 (4.5) | 3.3 (7.5) | 4.7 (9.2) | 5.7 (10.2) | 0.006 |

- Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

- * Number of days in the hospital directly prior to the day of transplant with no discharge.

- † Included in admissions, re-admissions, total initial transplant stay, and pretransplant LOS.

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have described the complexity and high profitability of LT for academic centers.4, 12 Recent single-center studies have described the tremendous increase in resource utilization associated with the substantial increase in severity of illness as a result of the MELD allocation system.9, 10 We investigated the total cost of LT, including the financial repercussions of MELD allocation and counting the pretransplant and posttransplant phases in a multicenter cohort of patients.

Given the results of our studies and others showing that high-MELD patients have acceptable posttransplant survival and are not associated with an increase in posttransplant cost, it is important that disincentives to perform transplants in the sickest patients do not lead to systematic exclusion of these patients from the LT list.13 Sound contracting and continuous improvements in practices would play a crucial role in providing fair treatment to patients and in receiving appropriate reimbursement to maintain the transplant center's operations.14, 15 It is reasonable to propose that proper reimbursement should account for the severity of illness, as has been implemented with the risk-adjusted DRG within the Medicare system. Finally, physicians could be paid by performance, and quality improvement programs would be beneficial.13, 14, 16

LOS has been used as a meaningful marker of cost and resource utilization in multiple studies of LT.3, 9, 10, 17 Our findings mirror prior data showing that sicker patients stay longer in the hospital during the initial transplant admission and in the pretransplant period.9, 10 Within the time span of our study, the transplant period accounts for only 55% to 75% of the total cost of LT. It is necessary to look beyond the transplant period to further understand the impact of the MELD allocation system on the economics of LT. Patients in the highest MELD group have longer ICU stays in the pretransplant period and stay longer in the ICU when re-admitted post-transplant.10, 18 Strategies to treat patients more efficiently during an earlier, more cost-effective phase are needed and must be encouraged.

Several clinical factors have been previously described as cost drivers in LT.3, 4, 10, 13, 17, 19-24 We were surprised to find that retransplantation did not independently drive charges as previously reported.25 It is possible that better patient selection, surgical techniques, and clinical expertise have modified the clinical results of these procedures. Alternatively, MELD score and retransplantation are collinear; thus, adjusting for MELD may reduce the impact of retransplantation in a multivariate model.

Multiple studies have also pointed to the increase in liver-kidney transplantation in the MELD era and the association of renal failure with increased resource utilization and poor outcomes.9, 26, 27 Therefore, we were not surprised to find that liver-kidney transplantation was a main cost factor for total, pretransplant, and transplant charges (along with the MELD score) in our study. We noted that patients with a higher BMI were in the highest MELD group, and this may partially represent fluid overload status in those with renal failure. We speculate that savings could be obtained if the transplant community were to implement new clinical and surgical strategies for the management of patients with renal failure within the LT period. A more equitable distribution of organs to reduce the MELD scores required to reach the top of the transplant list in all regions and pricing liver allografts according to their quality might also contribute to generating value in the system.28

We found that posttransplant charges are not different among different MELD groups. This might be interpreted as the success of LT in not only adding life years of quality to patients but also allowing patients to fully recover from severe illness.8, 14, 29, 30 We were surprised to find that patients with HCV, HBV, and HCC do not have a different posttransplant cost than patients with other liver diseases. Future studies could focus on understanding posttransplant costs and on minimizing the cost for different subsets of patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, there are those inherent to retrospective studies. Particularly in health economics, past charges may not be representative of future costs.3 Unique to LT are the dramatic changes that may occur over a short period, such as the current shift to riskier donors and sicker recipients.11, 31 Second, we did not discount for inflation or estimate the opportunistic cost of caring for LT at medical centers, which often run at capacity.13, 14 Third, there is a significant discrepancy in reimbursement across different regional, state, and institutional markets by both public and private payers that we were not able to capture. This discrepancy could not be thoroughly accounted for as we did not have center identifiers available for analysis and the insurance carrier had poor market penetrance in regions 1, 2, 6, and 9. Fourth, because of the broad utilization of global contracting practices, it became difficult to proper identify donor charges, and this probably skewed our data. Finally, we used charge data rather than cost data. Although most of the previous investigations of LT economics have used charges as a reliable measure of cost, charge data can be difficult to compare because of the inclusion of different cost items and modification of charges over time and between centers. Moreover, charges can be approximately 1.6 to 1.8 times greater than costs.32 Certainly, better methods to reliably convert charges to cost as well as larger data sets with single accounting methods will help us fully understand the economics of LT. However, the relative relationship between cost and charges is unlikely to vary across MELD groups and, therefore, should not invalidate our key findings.

In summary, we found that high-MELD patients incur significantly higher costs prior to and at the time of LT. Following LT, the MELD score is not a significant predictor of cost or re-admission. Our results highlight a need to develop strategies to treat sicker patients more efficiently and to work toward improving access to LT during an earlier, more cost-effective phase. Reimbursement systems should compensate providers appropriately for the care of complex patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Michael Abecassis (Northwestern University) and Marilyn Carlson (University of Washington) for the revision of the article.