Budd-Chiari syndrome: Radiologic findings

Abstract

Key Concepts:

- 1

Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome can be made on the basis of radiological imaging alone without the need for liver biopsy.

- 2

Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging all show various degrees of occlusion of the hepatic veins and/or inferior vena cava. Hypertrophy of the caudate lobe may also be seen.

- 3

Computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging give a better idea of hepatic perfusion. Image reconstruction of the inferior vena cava is also possible.

- 4

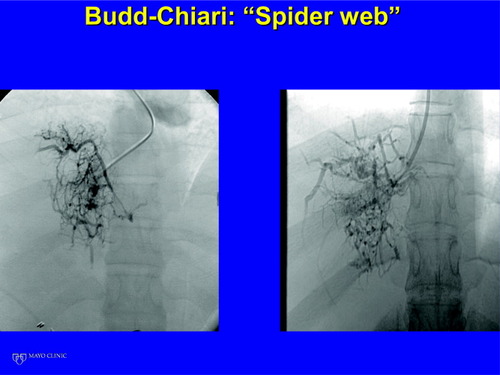

Hepatic venography demonstrates a spiderweb pattern diagnostic of Budd-Chiari syndrome.

- 5

Pressure measurements in the portal vein and infrahepatic inferior vena cava are necessary to determine whether a surgical portosystemic shunt will be successful.

- 6

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt provides definitive treatment in many patients; this is not discussed. Liver Transpl 12:S21–S22, 2006. © 2006 AASLD.

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by hepatic venous outflow abstraction at the level of the hepatic venules, large hepatic veins, and inferior vena cava (IVC) up to the confluence with the right atrium. Radiological imaging plays an important part in the evaluation of a patient suspected to have BCS. In fact, under current consensus recommendations, radiological imaging is sufficient to make a diagnosis of BCS. A liver biopsy is required only if radiological imaging is inconclusive.1

The radiological imaging modalities are ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nuclear medicine scans, and hepatic venography.

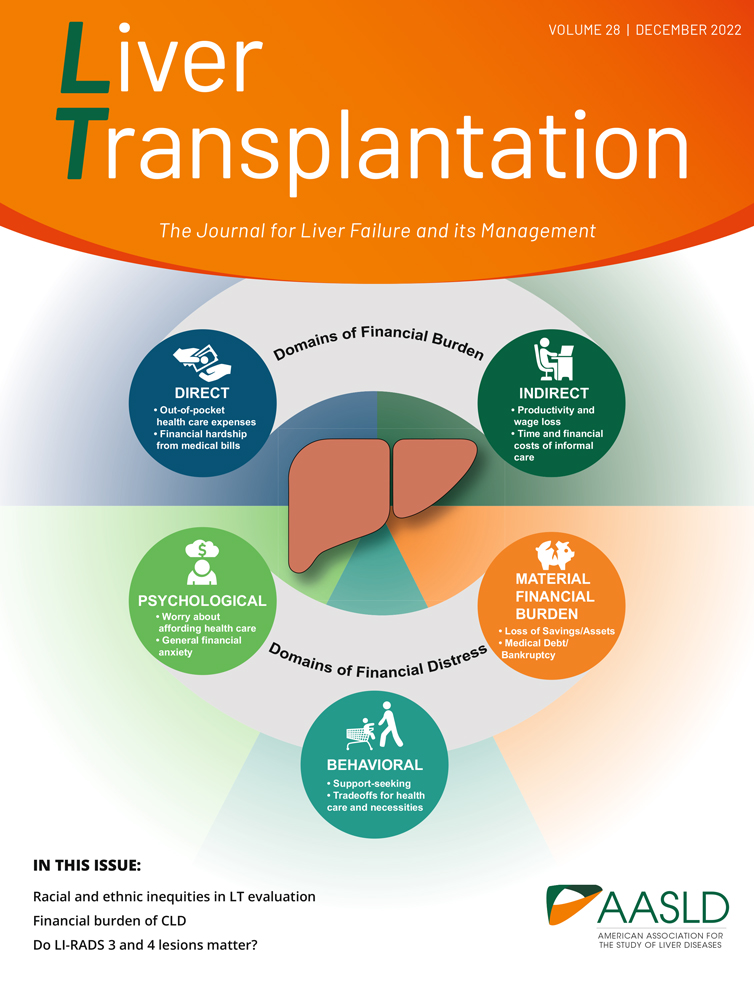

ULTRASOUND

Doppler ultrasonography of the liver has the sensitivity and specificity of approximately 85–90% for the diagnosis of BCS. It is considered the initial imaging technique of choice in a patient suspected to have BCS.2 In the normal liver, the right, left, and middle hepatic veins can be clearly visualized. The left and middle hepatic veins usually join together and drain into the IVC separately from the right hepatic vein. Doppler ultrasonography demonstrates flow in these veins toward the right atrium. Findings on ultrasonography consistent with BCS are nonvisualization of the hepatic veins, absence of flow in the hepatic vein, stenosis of or thrombosis within the hepatic veins, intrahepatic collaterals, and obstruction of the infrahepatic IVC.3 A hypertrophic caudate lobe may also be noted (Fig. 1).

Ultrasound demonstrating a thrombus in the hepatic vein.

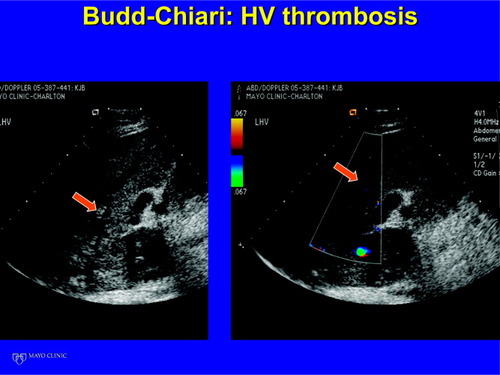

CT

CT is superior to ultrasound examination because necrotic areas of the liver are better seen, and better detail of perfusion of the liver is available. In the initial stages of BCS (Fig. 2), a mottled appearance may be noted related to inhomogeneous perfusion of the liver. The caudate lobe, which drains separately into the IVC, shows normal perfusion. With time, a collateral circulation develops that may be predominantly subcapsular. The caudate lobe increases in size and, with time, may be the only portion of the liver adequately perfused. Ultimately, changes of cirrhosis with a prominent portosystemic collateral circulation may be seen.

CT scan demonstrating inhomogeneous perfusion with relative sparing of the caudate lobe, and a thrombus in the IVC.

MRI

MRI has all the advantages of CT over ultrasonography.4 The advantage that MRI has over CT is that it can be used in patients with renal insufficiency.

HEPATIC VENOGRAPHY

The characteristic findings on hepatic venography are a spiderweb pattern. We recommend hepatic venography be carried out when the suspicion of BCS is high, even in the absence of typical findings on other radiological imaging. However, if a diagnosis is certain on ultrasound, CT, or MRI, hepatic venography is not essential. The normal hepatic venous pattern is of dichotomous branching without a significant collateral circulation between the venous branches. However, in BCS, there is a rich collateral circulation between the tributaries of the hepatic vein, which forms a spiderweb. In the initial stages, these collaterals are fine, which gives rise to a “fine spiderweb.” With long-standing BCS, the collaterals are thicker, giving rise to a “coarse spiderweb” (Fig. 3).

CT scan demonstrating inhomogeneous perfusion with relative sparing of the caudate lobe and a thrombus in the IVC.

We recommend pressure measurements when surgical therapy is being planned. With complete occlusion of all the hepatic veins, an adequate “wedge” pressure measurement is not possible. However, if one of the veins is patent, then balloon occlusion may be used to determine the hepatic venous wedged pressure. When surgical therapy is being planned, it is important to determine the portal vein minus infrahepatic IVC pressure. The portal vein pressure may be obtained by a direct transhepatic portal vein stick. However, a prominent collateral circulation in the subcapsular area of the liver may make the transhepatic stick more hazardous. In our hands, a surgical portocaval shunt or mesocaval shunt is successful if the portal vein minus infrahepatic IVC pressure is >10 mm Hg. If this gradient is <10 mm Hg, then we would recommend a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

In conclusion, radiological imaging is important in the diagnosis of BCS (ultrasound, CT, MRI, hepatic venography), in confirming the diagnosis of BCS (hepatic venography), in planning treatment (pressure measurements), and, finally, in providing definitive therapy in many patients (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts).