Navigating Pathways to Diagnosis in Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis: A Qualitative Study

Funding: This research was supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [1409-22214; NCT02481817].

American Laryngological Association. Combined Otolaryngology Society Meetings. Boston, MA, USA. May 2023.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

Objective

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis is a rare disease, and time to diagnosis is often prolonged. In the United States, some estimate it takes an average of 9 years for patients with similar rare disease to be diagnosed. Patient experience during this period is termed the diagnostic odyssey. The aim of this study is to use qualitative methods grounded in behavioral-ecological conceptual frameworks to identify drivers of diagnostic odyssey length that can help inform efforts to improve health care for iSGS patients.

Methods

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews. Setting consisted of participants who were recruited from those enrolled in a large, prospective multicenter trial. We use directed content analysis to analyze qualitative semi-structured interviews with iSGS patients focusing on their pathways to diagnosis.

Results

Overall, 30 patients with iSGS underwent semi-structured interviews. The patient-reported median time to diagnosis was 21 months. On average, the participants visited four different health care providers. Specialists were most likely to make an appropriate referral to otolaryngology that ended in diagnosis. However, when primary care providers referred to otolaryngology, patients experienced a shorter diagnostic odyssey. The most important behavioral-ecological factors in accelerating diagnosis were strong social support for the patient and providers' willingness to refer.

Conclusion

Several factors affected time to diagnosis for iSGS patients. Patient social capital was a catalyst in decreasing time to diagnosis. Patient-reported medical paternalism and gatekeeping limited specialty care referrals extended diagnostic odysseys. Additional research is needed to understand the effect of patient–provider and provider–provider relationships on time to diagnosis for patients with iSGS.

Level of Evidence

4 Laryngoscope, 134:815–824, 2024

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS) is a rare (prevalence 1:400,000), fibroinflammatory disease affecting the upper airway causing progressive airway scarring and stenosis that primarily afflicts middle-aged, Caucasian women. Otolaryngologists are essential to the diagnosis and care of patients with this rare disease. The diagnostic journey of patients with iSGS like others with rare disease is often tortuous and prolonged. These patients have shared experiences related to economic, social, and physical hardships while navigating the health care system.1-6 In fact, data suggest that rare disease patients like those with iSGS wait a mean of 9 years for diagnosis in the United States, and an estimated 40% receive treatment (including surgery) for erroneous diagnoses.1, 3

The iSGS patient's diagnostic journey navigating the health care system is known as their diagnostic odyssey.7 Understanding factors associated with brief and prolonged odysseys is critical to improving health care access and navigation for patients with iSGS.8, 9 To date, one case series has quantified diagnostic delays for iSGS patients; however, a qualitative approach is needed to understand why and how patients experience diagnostic delay.10 The aim of this study is to use qualitative methods grounded in behavioral-ecological conceptual frameworks to identify drivers of the diagnostic odyssey length that can help inform efforts to improve health care for iSGS patients.

METHODS

Ethics

This qualitative study was nested within a large prospective multicenter study trial (NoAAC) and approved by Vanderbilt University Medical Center (Trial Registration Number: NCT02481817; IRB #150917) and University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Boards (HSIRB 2020-0315).11 All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Written consent was obtained for a purposive sample of geographically diverse patients with iSGS to complete semi-structured interviews.

Sampling Strategy

Participant inclusion criteria included the following: (1) provision of signed informed consent; (2) willingness to complete the interviews and study protocols; (3) being English-speaking adults (≥18 years), and (4) having an iSGS diagnosis based on criteria previously published.11 Eligible patients were approached by study personnel to discuss study objectives and the semi-structured interview process. Patients in NoAAC were recruited using both traditional and novel methods. Traditional recruitment involved patient identification and recruitment by clinicians participating in the North American Airway Collaborative (NoAAC) network, 30 tertiary care centers in the United States, Australia, France, Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom. The novel recruitment method involved direct patient enrollment from a community of patients with iSGS on Facebook, “Living with Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis.”11

Patients were randomly selected from the larger NoAAC cohort from specific strata to ensure balance of U.S. region (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and West) and Canada. Also, considered in the sampling scheme was whether they underwent dilation or cricotracheal resection with a goal of 85% dilation and 15% resection patients. The intent was to ensure that we collected the diagnostic odysseys for patients across North America who ultimately underwent different treatments for iSGS.

Data collection methods and instruments

This qualitative study used individual semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions. Interviews were conducted by a trained facilitator (K.B.) that was not part of the participant's health care team. The interview guide was developed to direct conversations toward exploring the participant's experience with iSGS and its treatment and satisfaction with care received within the context of the diagnostic odyssey. The interview guide was developed, tested, and reviewed by our patient advisor (C.A.) and study team laryngologists (A.G., D.O.F.). The participants were asked to describe the process by which they received a final diagnosis, including time to diagnosis, alternative diagnoses, and treatments for symptoms.

Context

All interviews followed the interview guide and were conducted via phone during the study period. Phone interviews were selected because the geographic dispersion of the participants across North America obviated the ability to perform face-to-face interviews and video calls were less accessible in the pre-pandemic years these data were collected.

Data Processing

Each interview lasted 45–60 min and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim using services at rev.com®. The first author (C.D.S.) reviewed all transcripts for accuracy. Transcripts were then imported into NVivo Software for coding and analysis.

Researcher Characteristics

Two researchers (C.D.S. and K.B.) independently reviewed and refined the codebook and coded interviews using NVivo Software (http://www.qsrinternational.com). Both researchers have graduate-level training and expertise in qualitative research; one has a background in social psychology (K.B.) and the other is a rare disease patient with professional experience in health care administration and public health (C.D.S.). The larger research team includes otolaryngologists who treat and study iSGS (N.N., D.O.F., and A.G.), a patient and moderator of the online community from which participants were recruited (C.A.), a psychology professor with expertise in behavioral medicine (D.S.), and a health services researcher who works in specialty care surgery (S.F.T.).

Analysis

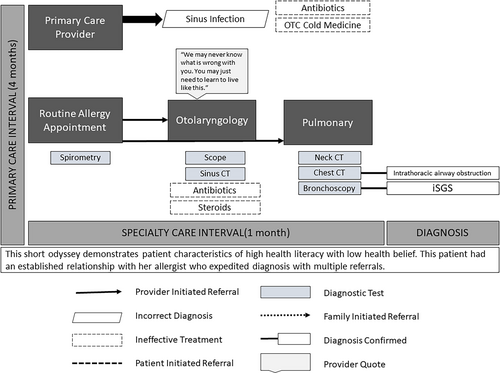

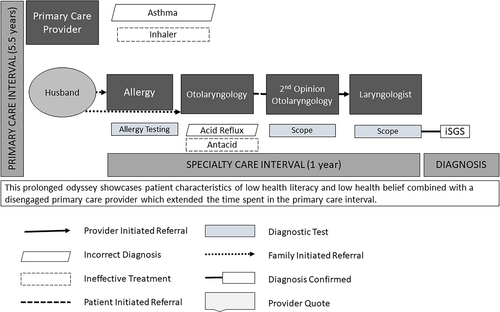

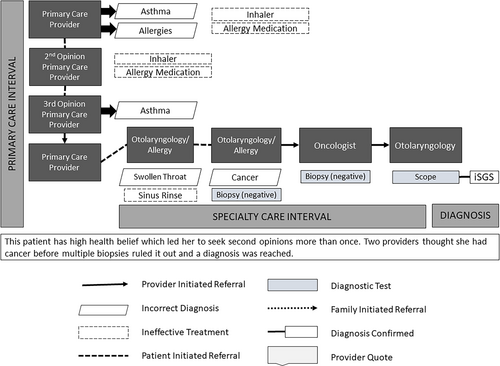

Directed content analysis of de-identified interview transcripts was performed using content analysis. Interviews and content analysis continued until thematic saturation, defined as no new themes identified in at least two consecutive interviews. We used major themes from the conceptual frameworks to visually represent each interview in the relational content analysis phase (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).7, 12 Content analyses were conducted using both deductive codes derived from conceptual frameworks and inductive codes derived from interviews. The codebook was developed by two authors (C.D.S. and K.B.) and reviewed by all members of the research team. Two team members (D.O.F. and S.F.T.) reconciled any coding disputes at weekly meetings. Descriptive statistical analysis of participant demographic data was completed in SPSS, and Student's t-tests used to calculate differences in TTD between patients. All results are presented from the patient perspective, include patient perception of provider intent, and reported following SRQR guidelines.13

Research Paradigm

The Diagnostic Odyssey Framework and Ryvicker's behavioral-ecological conceptual framework on health care access and navigation were used to contextualize content analysis of interview data.7, 12 The Diagnostic Odyssey Framework consists of three distinct intervals: (1) patient interval (from symptom onset to presentation to care), (2) primary care interval (from presentation to care to specialist referral), and (3) specialty care interval (from specialist referral to diagnosis).7 Ryvicker's framework is not specific to rare disease patients but examines health care, social, and built environments as causal and moderating factors in care access and navigation. Combining these frameworks offers a concrete way to contextualize behavioral-ecological factors that influence iSGS patients in each odyssey interval before their definitive diagnosis. Each patient's odyssey provided a focused timeframe within which to analyze relevant behavioral-ecological health-access themes.

Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

We triangulated our findings ex post facto with existing published scholarly and lay narratives of rare disease patients' experiences to ensure fidelity of our findings.1-8, 10 In addition, an iSGS patient and advocate (C.A.) was involved in all study development, data coding, and analysis to ensure the validity of our results.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Thirty patients with iSGS were interviewed (female: 100%; white: 87%; mean age: 48 years, range 25–70) from the United States (87%) and Canada (13%). The patients saw an average of four providers before a final diagnosis (95% CI 3.6–5.2) and had a median time to diagnosis (TTD) of 21 months (IQR 12–46). Women in the youngest age quartile (<36 years) had the shortest TTD (mean: 9 vs. 38 months, 95% CI 5–53, p = 0.012). In all, 18 (60%) were diagnosed ≥3 years after symptom onset.

Eight patients (27%) who bypassed primary care (PCP) and self-referred to specialty care experienced a median TTD of 27 months (IQR 9–57). Patients whose PCP directly referred them to the diagnosing provider experienced a median TTD of 12 (IQR 7–36) months (n = 5, 17%). Specialist-to-specialist referral (cross-referral) resulted in a median TTD of 18 months (IQR 10–45; n = 17, 57%). Overall, otolaryngologists ended most iSGS patient's odysseys (n = 25, 83%). Patients who had preexisting strong relationships with specialty care providers (e.g., allergy and pulmonology) experienced decreased TTD (median TTD: 8 months (IQR 5–60), n = 7, 23%).

Nearly every participant (n = 29, 96%) reported at least one misdiagnosis for their dyspnea, most commonly asthma (n = 26, 87%) or allergies (n = 9, 30%). Four patients (13%) reported their provider told them that they may have cancer (i.e., thyroid, neck, and tracheal) before biopsy ruled it out. Four patients (13%) were diagnosed with iSGS while seeking care for unrelated medical concerns. Twenty-five (83%) received medication to treat dyspnea, most commonly inhalers (n = 18, 73%), which patients reported to have had no effect on symptoms or disease progression. Four patients (13%) underwent a surgery to treat their dyspnea before definitive iSGS diagnosis (e.g., septoplasty, cholecystectomy, and fundoplication), which did not improve their symptoms.

Relational Content Analysis

Three themes from Ryvicker's framework were associated with odyssey duration and efficiency: (1) patient motivational characteristics (e.g., self-efficacy), (2) patient social environment (e.g., relationships), and (3) provider factors (Table I). We describe these themes below.

| Diagnostic Odyssey Interval | Ryvicker's Behavioral-Ecological Factor | Description | Elements At Work in the Diagnostic Odyssey | Effect on Length of Patient's Diagnostic Odyssey | % Reporting Shared Experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Individual characteristics (medical self-management) | Describes the patient's role in their own care-seeking and planning, treatment, and disease management | Self-referral to new specialty care providers, seeking second opinions, willingness to travel across state lines for care, and willingness to pay out-of-pocket for care | Rare disease patients may self-refer or request referrals and second opinions more often than chronic care patients who also must employ self-management techniques. RD patients may show a willingness to travel further or pay out-of-pocket for treatment or consults (due to a lack of resources in the health care environment) during prolonged diagnostic odysseys. | 87% (26/30) |

| All | Individual characteristics (self-efficacy, health belief) | The belief that one has control over one's health and outcomes, sometimes used as a proxy to determine potential for self-management. | Self-advocacy for new treatment, consult, or medication during prolonged odysseys | Frustrated patients whose symptoms do not improve after months of treatment or disappointing interactions with health care providers may feel a sense of responsibility to self-advocate for something different, helping them navigate the health care system. | 73% (22/30) |

| All | Social environment (bonding social capital) | Trusted relationships between peers who share a social identity | Coworkers mention symptoms patients may not have previously recognized Friends or partners comment on physiologic changes during all stages of odyssey |

Close relationships may empower patients to seek medical attention for the first time or go back after symptoms. Patients may not return to seek care after a prolonged odyssey without the support of family, friends, or peers. | 93% (28/30) |

| PCI-SCI | Provider factors (medical paternalism) | Patient frustration or dissatisfaction with providers or care team interactions due to symptom dismissal and reluctance to refer. | Suggestions that symptoms are psychosomatic or that the patient is erring in the medical management of the condition | Rare disease patients may experience stigmatizing interactions with providers who insist patient error is to blame for lack of symptom improvement. This may result in continued extraneous and unnecessary treatment for the patient. | 53% (16/30) |

| PCI-SCI | Provider factors (Gatekeeping) | Patient dissatisfaction with inappropriate referrals. | Providers refer to specialists but referral does not result in a diagnosis. | RD patients may spend more time than other populations cycling through different specialty care visits. | 37% (11/30) |

| PCI-SCI | Provider factors (provider–patient relationship) | Patient has previously established close relationships with specialty care providers | Patients reported trusting providers with whom they already had an established relationship, adding that this level of trust invited more open discussion regarding their care and diagnostic pathway. | Strong relationships between patients and specialty care physicians may drastically decrease TTDs. | 23% (7/30) |

| PCI-SCI | Social environment (bridging social capital) | Trusted relationship between those who recognize a difference in socio-demographic identity (e.g., social class, age, and position of power) | Supportive managers, supervisors, subordinates, clients, or children encourage patients to seek care | The power differential seen in some bridging social capital relationships may hold substantial weight for a patient during the diagnostic odyssey. Simple observations from a manager or child on the patient's well-being may be more effective in motivating individuals to seek care. | 27% (8/30) |

- PCI = primary care interval; SCI = specialty care interval.

Patient Motivational Characteristics

Self-efficacy was the predominant intrinsic patient characteristic affecting the iSGS diagnostic odyssey. Health-related self-efficacy is the belief one has control over their health outcomes and has a direct positive association with a patient's commitment to their health goals.14 Patients with high levels of self-efficacy viewed barriers to care as surmountable and persisted in their efforts. Patient tenacity often resulted in a referral from primary to specialty care (Table II, Quote #1) or self-referral to specialty care (Table II, Quote #11, Fig. 1).

| Facilitators | Supporting Quotation | Barriers | Supporting Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy, High health belief | #1. If I hadn't been really crabby with the allergist that day, ‘cause he said: “It's under control.” I said, “no it's not.” He said: “Yes” and I said: “No it's not.” He said: “Would you like a second opinion?” I said: “Yes.” If he hadn't have sent me on the second opinion, I don't know how long it would have taken to find it. (CC, 53-year-old, 72-month diagnostic odyssey) | Self-referral | #2. One of the things that was really frustrating to me is that almost everybody that I saw neurologist, cardiologist, two ENTs, all these different people, almost all of them were my own initiative. Like I went looking for these people thinking, “What other kind of doctor is there that might in any way possible be related to this?” A lot of them just nothing is wrong with you. I said, “Who else can I go to?” They said, “We don't know.”(J, 38-year-old, 48-month diagnostic odyssey) |

| #11. That part was frustrating to see the ear, nose, and throat doctor here in town, who we know quite well. You almost felt like he just kind of blew it off, versus … The one (50 miles away) was much better, asked me many, many questions, wanted several different kinds of tests done. I felt like he was a lot more thorough. Like I said, we didn't go back. I just decided I needed a second opinion and was able then to be able to get it resolved that way. (Patient Q, 48-year-old, 72-month diagnostic odyssey) (Fig. 1) | Care coordination | #3. I mean, right now I work part-time and I almost feel like I'm afraid to start working full-time just because I do have to take off to go see doctors, to go do, you know … I just went to go see an ENT and then I got to go see the specialist and then I've got to schedule for surgery. I almost hesitate to go get a full-time job because of the medical demands of this. (R, 49-year-old, 12-month diagnostic odyssey) | |

| #6. Yeah, initially I complained to my first doctor and there were several different times, and it was finally this last one I pushed, I'm like, “I know I'm out of shape, but this is not out of shape.” I mean, I can't walk up my stairs. If I sweep, I just get so winded. That's not out of shape for me…(M, 44-year-old, 24-month diagnostic odyssey) | #4. …having to go to a doctor and explain over and over and over again what this is and have them look at me like I'm crazy and with disbelief…I just dread it when it's a new doctor. I just dread it…I think with this disease, you absolutely have to be your own advocate and your own doctor. (L, 44-year-old, 18-month diagnostic odyssey) | ||

| #5. [My primary care physician] put me on [asthma] medicine and it never got better. Then I went back to her again (sic) and still they didn't know what was wrong with me. Then she just gave me more meds, gave me more inhalers. Then I was like, “You know what? I want a second opinion.” Then I went to the health center and I spoke to another doctor. Well, he told me the exact same thing she did, and he was going to want to start me on the same meds all over again that she had put me on.I basically started crying because I was just so frustrated by this point, so I was like, “Just forget it. I'll just go back to her.” (G, 36-year-old, 24 month diagnostic odyssey) | |||

| Low health literacy | #7. I just assumed like, “Well, maybe I'm just out of shape or something else.” …I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. That doctor just kept telling me, “Oh your shortness of breath is something like related to that. You just have something else wrong with you.” (J, 38-year-old, 48-month diagnostic odyssey) | ||

| #8. But yeah, it was probably good six to 8 months before [I got a referral], ‘cause I just thought, “Well, maybe it's a cold.”(DD, 62-year-old, 8-month diagnostic odyssey) | |||

| Low health belief | #9. Anyways, [the pulmonologist] was the one that thought it was asthma and it was probably about 8 months of me trying this treatment before I was like, okay, something's wrong. I probably still would have just kept on his treatment, had the respiratory therapist in the ER not said to me, something's not right.(E, 35-year-old, 12-month diagnostic odyssey) | ||

| 10. I went into my general practitioner, and he said, “You have asthma.” He put me on an inhaler. I would use that every day, but (sic) it would get to where I just couldn't catch my breath…I probably did that for maybe 4 or 5 years. Dealt with [not being able to catch my breath] until it just got so bad that (sic) when I first had the first dilation, [my trachea] was the size of a one-year-old's. (Q, 48-year-old, 72-month odyssey) (Fig. 2) | |||

Though high levels of self-efficacy resulted in a quicker transition to specialty care (where iSGS was diagnosed), patients reported that managing care coordination was exhausting and time-consuming and commensurate with a full-time job (Table II, Quote #3). In addition to coordinating care, undiagnosed iSGS patients felt they had to explain their story and symptom history to each new provider they encountered, which they reported was overwhelming and disheartening (Table II, Quote #4–5).

High levels of health belief also facilitated referrals during odysseys (Table II, Quote #6), whereas low levels of health belief (i.e., lack of belief that symptoms were serious enough to seek help) and health literacy (i.e., a poor understanding of symptom presentation) were barriers to efficient diagnosis (Table II, Quote #10, Fig. 2). Odysseys were particularly inefficient and prolonged for iSGS patients who experienced high levels of health belief and low levels of health literacy (Table II, Quote #2).

Social Environment

Patients with high levels of social connectedness and trust (in both familial and workplace settings) reported improved utilization of appropriate health care. These elements comprise the patient's social environment and were the most mentioned factors affecting odyssey efficiency. Twenty-eight patients with iSGS (93%) credited family members or coworkers as the impetus for care-seeking. Two patients who did not mention their social network reported high levels of disease-driven isolation and depression.

When self-doubt or self-defeat (due to prolonged odysseys or frustration with providers) prevented patients from seeking care, family, or friends encouraged them to seek further help (Table III). This usually occurred after cycling through their PCP and specialists (Table III, #12–14, Fig. 2). Coworkers also prompted care utilization, especially among patients who believed they were otherwise healthy (Table III, #15–17).

| Facilitators | Supporting Quotation | Barriers | Supporting Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | #12. My husband was clueless. He kept saying, “What's wrong with you?” I kept saying, “I don't know what's wrong with me.” Like I said, a lot of the people I work with would ask me do I have asthma? They seemed concerned that they wanted to help me get better, but nobody knew what was wrong with me. (T, 56-year-old, 5-month diagnostic odyssey) (Fig. 2) | None | |

| #13. Finally, my husband's like there's gotta be something else wrong here. We decided to [self-refer to] the ear, nose and throat doctor here in town…(Q, 48-year-old, 72-month diagnostic odyssey) (Fig. 2) | |||

#14. I felt like I was crazy…The only reason I went to the doctor is my daughter forced me, and my husband, because I just was tired of being told I was fine. (Z, 66-year-old, 36-month diagnostic odyssey) (Fig. 2) |

|||

| Coworker support | #15. If it wasn't for my coworker saying, “Oh my gosh, you've gotta go get your breathing checked out” I guess I wouldn't have even thought anything was wrong (DD, 62-year-old, 8-month diagnostic odyssey) | None | |

| #16. Finally, one of my higher up managers heard me, with this wheezing sound and sent me directly to the doctor and said do not come back until you get an answer because there's something seriously wrong (K, 44-year-old, 36-month diagnostic odyssey) | |||

| #17. People at work were saying, “I don't know what you're doing here.” I'm like, “I don't even know what I'm doing here. But according to my physician he said I should be able to function,” so I was functioning but I don't think I should have been at work now…looking back at it. (S, 52-year-old, 72-month diagnostic odyssey) | |||

Provider Factors

Provider factors were the next most important determinant of odyssey efficiency and TTD for iSGS patients. Patients with long TTDs reported provider disbelief or refusal to refer. Conversely, patients with established relationships with specialists were more likely to experience shorter TTDs.

Provider Disbelief

Patients reported providers (both primary and specialty) continued to prescribe the same medication (e.g., rescue inhalers) instead of referring when the iSGS patient's dyspnea did not improve. In some cases, providers suggested the patient was not using medication correctly (Table IV, #19) or their symptoms were psychosomatic in nature (Table IV, #20). After prolonged symptom dismissal from providers, patients were likely to describe feeling as if it was all in their head and expressed a reluctance to return if they “weren't really sick” (Table IV, #18).

| Facilitators | Supporting Quotation | Barriers | Supporting Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider–patient relationship | 22. I had a routine visit with my allergy doctor…Then I kind of unloaded on the allergist about [my symptoms]. He really listened to me… Part of the problem in healthcare today is everybody's so busy…and that's what impressed me so much with my allergist, was somebody who knew me for 5 years but really listened to what I was saying…Then even after I walked out the door…he still persisted in trying to figure out what was wrong with me. (T, 56-year-old, 5-month diagnostic odyssey) (Fig. 3) | Provider disbelief | 18. I'm a nurse and I was like, “Well, I don't want to go back and be a complainer because I'm not sick, I don't have a fever. It's just this cough and what I think is maybe some kind of drainage. I didn't do anything about it. (T, 56-year-old, 5-month odyssey) |

| 23. So honestly the doctor that I finally got to listen to me, was very quick [sic] very quick to know this isn't something I can deal with. You need someone else, and they sent me to the ENT (M, 44-year-old, 24-month diagnostic odyssey) | 19. It was, “Here's an inhaler. If that's not working, you're not doing it properly. Here's a spacer. Try that with your inhaler.” Other than that there was no other possible diagnoses that they offered or any other treatment that they offered. (H, 36-year-old RN, 12-month diagnostic odyssey) | ||

| 20. One doctor actually insinuated that it was probably in my head, like a panic type attack thing and it was causing me to, you know… feel even smaller…yeah, it's hurtful. (M, 44-year-old, 24-month diagnostic odyssey) | |||

| Willingness to refer | 21. … fought with [my primary care provider] for about half an hour to get a referral to an ENT. I kept telling her, “It's not asthma, it's something else. I want to be seen.” She just kept telling me I was fine. I needed to just use the inhaler and give it more time. I think she just finally gave in because she was tired of fighting with me on it. (H, 36-year-old RN, 12-month diagnostic odyssey) | ||

Willingness to Refer

Nine iSGS patients experienced at least a four-year diagnostic odyssey (30%). Seven patients reported their PCP refused to refer to specialty care, because they were confident in their original diagnosis (7/9, 78%). Of those, three waited and pressured their PCP for a referral (3/7, 43%) and four patients bypassed their PCP altogether and self-referred to specialty care (4/7, 57%). Eleven iSGS patients (11/30, 37%) described pleading with providers for referrals or to believe the working diagnosis was incorrect (Table IV, #21).

Provider–Patient Relationship

TTDs decreased and odyssey efficiency increased when patients had a previously established relationship with a specialty care provider (Table IV, #22; Fig. 3). Cross-referral to otolaryngology ended 17 (17/30, 57%) iSGS odysseys indicating higher efficiency and more appropriate referrals between specialists. Seven patients (7/30, 23%) reported extra effort by their specialist ended their odyssey. These iSGS patients experienced the shortest TTDs, regardless of age (median 8 months). The most reported provider factors in short odysseys were willingness to listen, work with the patient, and refer (Table IV, #23).

DISCUSSION

This study examined pathways to diagnosis for patients with iSGS, a rare disease of the airway. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine behavioral-ecological factors that influence iSGS patient health care access and navigation from symptom onset to diagnosis. Overall, nuances in patient–provider and social relationships proved critical to diagnostic odyssey length and efficiency.

Diagnosis Facilitators

Patient–Provider Relationships

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis patients who had established strong relationships with specialty care providers (e.g., allergy and pulmonary) experienced more efficient, shorter diagnostic odysseys. They expressed high levels of trust in their specialist and felt providers were invested in helping them obtain a final diagnosis. This is consistent with extant literature establishing the importance of strong specialist–patient relationships and patients as partners in decision-making.4, 16-18 Research investigating effects of patient–provider relationships on decreased time to diagnosis and odyssey efficiency has potential to reduce patient and system burden.

Referral Patterns

In this study, specialist-to-specialist referral (cross-referral most often to otolaryngology) ended most iSGS odysseys, followed by self-referral to specialty care. This is consistent with published evidence that patient-centered care improves with cross-referral within multidisciplinary teams (e.g., cancer care); however, effect of self- and cross-referral on TTD in rare disease remains understudied.19-21 Many European countries have moved to a nationally based rare disease management plan, implementing disease registries and a coordinated research effort.2 This calls for coordinated care and referrals across multidisciplinary teams to streamline and improve care for rare disease patients.3, 5, 16 Our results support further collaboration and cross-referral between specialists during diagnostic odysseys to decrease TTD for iSGS patients.

Social Environment

Universal factors facilitating care access throughout iSGS diagnostic odysseys were (1) worried family or friends pressuring the patient to seek care and (2) social support to overcome psychosocial barriers to utilization. We found social capital (i.e., trusted relationships between peers of a shared social identity) functioned as a direct factor in realizing access to care. The importance of social support for rare disease patients and their families is well-documented.4, 5, 18 This supports work which demonstrated when families (or patients) suggest a rare disease, diagnosis is accelerated.2, 3 This contributes to understanding how social environment moderates the relationship between potential and realized care access.

Diagnosis Barriers

Medical Paternalism—Provider Dismissal of the Patient Expert

Providers' overconfidence in diagnosis or failure to properly synthesize information (diagnostic errors rooted in medical paternalism) proved a defining barrier to diagnosis.22-24 Patients with iSGS in this study reported that PCP reluctance to refer often delayed their diagnosis by years. These patients reported feeling dismissed by their providers after months of ineffective treatment and felt this led to inefficient, prolonged odysseys. This is consistent with evidence that found delayed diagnosis for iSGS patients resulted in unnecessary treatments, surgeries, emergency department visits, and increasing health care costs.15 Despite a move towards patient-centered care, medical paternalism still complicates diagnostic odysseys.4, 16, 25, 26 From the provider perspective, this phenomenon may be driven by the intransigence of “horses not zebras” approach to diagnosis, in which the most likely and most common explanation of patients' symptoms is retained, even if they are refractory to first-line therapy.

When iSGS patients were asked what they most wanted providers to know, most wanted providers to listen to patients when they re-present with the same or worsening symptoms. Patients did not expect PCPs or specialists to be able to diagnose myriad rare diseases, but they held an expectation that providers refer appropriately if symptoms do not respond to treatment. This bolsters a systemic move to a patient-centered care model focusing on the patient's lived experience and is well-represented in patient advocacy, provider bias, and rare disease literature.2, 3, 22, 27-31

“Gatekeeping” Referral Patterns

Patients with the most prolonged diagnostic odysseys described a cycle of bouncing between their PCP and specialists. Gatekeeping, requiring patients to receive a referral from their PCP to access specialty care, caused delay in diagnosis.16, 21, 32 Although gatekeeping can control inappropriate referrals and costs by limiting unnecessary visits with specialists, little research exists regarding its effect on patient and provider outcomes.17, 21, 32 For iSGS and other rare disease patients, the referral cycle from primary to specialty care and back again puts financial strain on the system and patient in addition to delaying diagnosis.3, 6, 25, 33, 34 This finding supports recent debate questioning benefits of traditional gatekeeping on both system and individual level outcomes.19, 21, 25, 33, 34

Patients reported an implicit form of “gatekeeping” as reluctance to seek out specialty care without a referral from their PCP. This was attributed to a combination of individual factors, including low health literacy and low self-efficacy or health belief, which were exacerbated by providers' denial of disease. Patients with iSGS, who acted as their own gatekeepers experienced long TTDs and were more likely to undergo a higher number of inappropriate treatments under the care of their PCP. This contributes to understanding the patient role in referral patterns.19

The interaction of explicit and implicit gatekeeping with medical paternalism proved detrimental for undiagnosed iSGS patients, resulting in the longest, most inefficient odysseys.

LIMITATIONS

Recall bias is possible as semi-structured interviews were completed as long as 10 years after diagnosis; specific details surrounding diagnostic odysseys may be lost. However, we expect better than average recall, as most odysseys are emotionally taxing and often affect all aspects of life. The iSGS patient population is socio-demographically homogenous. The high burden and inequity our iSGS patient population face is notable here, but this may not generalize to rare disease patients from socio-demographically vulnerable populations. Finally, the diagnostic odyssey of patients with iSGS may differ based on the whether they are in a country/setting with a public or private health care system, and, in the latter case, the type of insurance coverage. We did not collect data on these features directly and identify any differences in experience or time to diagnosis between the United States and Canadian participants. Nonetheless, understanding how the health care system affects access to timely care for patients with iSGS is an area that deserves further study.

CONCLUSION

Our study describes the impact of behavioral-ecological factors on iSGS patients' diagnostic odysseys. Social environment, individual patient characteristics, and provider factors affected diagnostic odyssey length and efficiency. The patients reached a final diagnosis quicker when they had high levels of medical self-efficacy, a strong social support system, and established relationships with primary or specialty care providers who were willing to refer. Our findings within the iSGS population highlight the need for a better understanding of the collective impact of referral patterns and patient relationships on diagnostic delay.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This was a North American Airway Collaborative (NoAAC) Study. Research in the North American Airway Collaborative was supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute under award number 1409-22214.