Mood, Anxiety and Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Evidence of Central Nervous System Involvement?

Editor's Note: This Manuscript was accepted for publication on July 1, 2020.

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

MMS and TSC received funding from Kantonsspital Aarau, Department of Otolaryngology, Funded by Research Council KSA 1410.000.128.

The authors acknowledge Sofia Burgener and Vanessa Kley for their help with data collection.

Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine the burden of depressed mood and anxiety in COVID-19, and associated disease characteristics.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective, cross-sectional study of 114 COVID-19 positive patients diagnosed using RT-PCR-based testing over a 6-week period. The two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) and the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-2) were used to measure depressed mood and anxiety level, respectively, at enrollment and for participants' baseline, pre-COVID-19 state. Severity of smell loss, loss of taste, nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea/mucus production, fever, cough, and shortness of breath (SOB) during COVID-19 were assessed.

Results

PHQ-2 and GAD-2 significantly (P < .001) increased from baseline to enrollment. PHQ-2 was associated with smell loss (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] = 1.40, 95% CI, 1.10–1.78, P = .006), age (aIRR = 1.02, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, P = .006), and baseline PHQ-2 score (aIRR = 1.39, 95% CI, 1.09–1.76, P = .007). GAD-2 score was associated with smell loss (aIRR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.02–1.62, P = .035), age (aIRR = 1.02, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, P = .025) and baseline GAD-2 score (aIRR = 1.55, 95% CI, 1.24–1.93, P < .001). Loss of taste also exhibited similar associations with PHQ-2 and GAD-2. PHQ-2 and GAD-2 scores were not associated with severities of any other symptoms during the COVID-19 course.

Conclusions

Despite the occurrence of symptoms—such as SOB—associated with severe manifestations of COVID-19, only the severities of smell and taste loss were associated with depressed mood and anxiety. These results may raise the novel possibility of emotional disturbance as a CNS manifestation of COVID-19 given trans-olfactory tract penetration of the central nervous system (CNS) by coronaviruses.

Level of Evidence

3 Laryngoscope, 130:2520–2525, 2020

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has quickly spread all across the world and represents a global health emergency.1-3 COVID-19 has classically been described by symptoms of fever, cough, and shortness of breath as well as constitutional symptoms such as fatigue and myalgias,2, 4, 5 although more recent studies have described a myriad of other COVID-19 clinical manifestations including chemosensory dysfunction, ie, decreased sense of smell and taste.6 With a mortality rate that is widely publicized and understood in the lay public to be an order of magnitude greater than influenza, COVID-19 may be a significant source of emotional strain on the affected individual. Previous studies of endangering diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, or heart disease, have found that affected patients experience much higher rates of depression and anxiety.7-9 At present, however, the emotional burden of COVID-19 on affected patients remains largely uncharacterized.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, depression and anxiety have been shown to be significant burdens on society in general.10-13 The mental health of healthcare workers and relatives of COVID-19 patients has also been studied and found to be negatively impacted during the pandemic.14-16 There is also some suggestion that COVID-19-related interventions, such as quarantining may contribute to anxiety, stress, or depression.17 While the full impact of COVID-19 on patients' emotional wellbeing has not yet been determined, it is reasonably hypothesized that mental health disorders will be a major challenge in survivors of COVID-19.18 It is therefore of great importance to understand the burden of emotional distress caused by COVID-19 as well as associated factors that may modulate that burden.

In this study, we investigated depressed mood and anxiety in a cohort of patients with COVID-19. Our objective was to both quantify the burden of depressed mood and anxiety in COVID-19 as well as to identify factors that would be associated with the degree of that burden. Specifically, we focused on the severity of COVID-19 symptoms—as reflections of ongoing COVID-19 pathophysiology—as risk factors for greater burdens of depressed mood and anxiety.

METHODS

Study Participants

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Kantonsspital Aarau (Ethikkomission Nordwest und Zentralschweiz) in Aarau, Switzerland. This study was carried out as a secondary objective of a previously described study of the prevalence of sinonasal symptomatology in COVID-19.19 Patients, receiving their care at the Kantonsspital Aarau, who tested positive for COVID-19 at this cantonal hospital between March 3, 2020 and April 17, 2020 were identified and contacted. All patients had been tested for COVID-19 using an RT-PCR-based test. All patients who participated provided consent to participate in this study. All patients were then contacted by telephone up to three times in order to complete the study. Patients who were not reachable with three telephone calls were excluded. Patients who were hospitalized were also approached in person. Patients who were in intensive care units or who were deceased were excluded.

Study Design

This was a prospective, cross-sectional study of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at the Kantonsspital Aarau. This study was carried out as a secondary objective of a previously described study of the prevalence of sinonasal symptomatology in COVID-19.19 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants including age, gender, smoking history (classified as never smoker, past smoker, current smoker), and comorbidities were collected.

A standardized questionnaire was given to participants. Depressed mood was quantified using the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2),20 which has been developed as a screening tool for major depressive disorders (MDD) as it reflects the two major symptoms of MDD. Specifically, the PHQ-2 queries the frequency of anhedonia and feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. We similarly used the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-2) as measure for the burden of anxiety.21 The GAD-2 queries the frequencies of “feeling nervous/anxious/on edge” and “not being able to stop or control worrying.” The PHQ-2 and GAD-2 both assess the frequency of each symptom over a 2-week period and use a scale of “Not at all” (=0), “Several days” (=1), “More than half the days” (=2), and “Nearly everyday” (=3). Participants completed the PHQ-2 and GAD-2 according to how they felt on the day of the interview at enrollment and also according to how they felt immediately before becoming affected by COVID-19.

Related to their COVID-19 disease course, participants were asked how many days they had been experiencing symptoms of COVID-19. Then participants were asked to rate symptoms of decreased sense of smell, decreased sense of taste, nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea/nasal mucus production, fever, cough, and shortness of breath on a scale of 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe)—a scale that was modeled on the validated nasal symptom score.22 Participants were asked to rate these symptoms at enrollment, at their worst during the COVID-19 disease course, and at baseline prior to being affected by COVID-19.

Statistical Analysis

All analysis was performed with the statistical software package R (www.r-project.org). Basic, standard descriptive statistics were performed. Correlation was performed using Spearman's method. Negative binomial regression was used to check for association with PHQ-2 and GAD-2 scores (as dependent variables). Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to detect collinearity, which was suspected for severity ratings of decreased sense of smell and taste. The multivariable models included predictor variables: age, gender, smoking history and burdens of the symptoms of decreased sense of smell or taste, nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, fever, cough and shortness of breath. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) are reported for negative binomial regression results.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants

A total of 114 participants (45.6% male, 54.4% female) were recruited, with mean age 44.6 years (SD: 16.1). Non-smokers comprised 70.1% of participants while 19.3% were previous smokers and 10.5% were currently smoking. Only one participant had been previously given a formal diagnosis of anxiety and another participant had previously been diagnosed with anxiety and depression (and was being treated for it). Patients reported that their COVID-19 symptoms began with a mean 12.3 days (SD: 7.2; median: 11.5 days, range: 0–31 days) prior to the enrollment interview (four patients felt they could not reliably remember how long prior their symptoms started). The severity of symptoms experienced at enrollment, at their worst during the COVID-19 disease course and at baseline are shown in Table I.

| COVID-19 symptom severity, mean (SD) | Enrollment | Its worst during COVID-19 | Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased sense of smell | 0.75 (1.16) | 1.69 (1.42) | 0.05 (0.35) |

| Decreased sense of taste | 0.66 (1.06) | 1.63 (1.36) | 0.03 (0.28) |

| Nasal obstruction | 0.42 (0.73) | 0.98 (1.10) | 0.09 (0.31) |

| Mucus production | 0.20 (0.46) | 0.55 (0.86) | 0.06 (28) |

| Fever | 0.36 (0.72) | 1.47 (1.17) | 0.0 (0.0) |

| Cough | 0.66 (0.84) | 1.39 (1.16) | 0.09 (0.39) |

| Shortness of breath | 0.40 (0.73) | 0.93 (1.18) | 0.04 (0.18) |

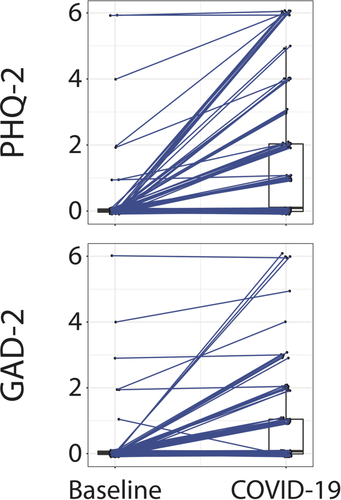

At enrollment, 47.4% of participants had a PHQ-2 score of at least 1 and 21.1% of participants had a PHQ-2 score of at least 3. Similarly at enrollment, 44.7% of participants had a GAD-2 score of at least 1 and 10.5% of participants had a GAD-2 score of at least 3. PHQ-2 score at enrollment (mean: 1.4, SD: 2.0) was significantly greater (P < .001) than participants' pre-COVID-19 baseline PHQ-2 score (mean: 0.2, SD: 0.9). GAD-2 score at enrollment (mean: 0.9, SD: 1.4) was also significantly greater (P < .001) than participants' baseline GAD-2 score (mean: 0.2, SD: 0.8). The changes in PHQ-2 and GAD-2 scores from baseline to enrollment, after the COVID-19 diagnosis, is shown in Fig. 1.

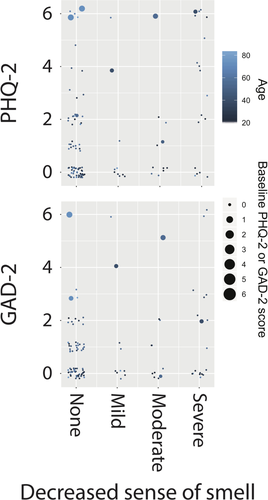

Association of Depressed Mood with COVID-19 Symptom Burden

We next checked for association between PHQ-2 scores and patient characteristics, including symptom severities at enrollment (Table II). On univariate association, we found that the PHQ-2 score was positively associated with age (IRR = 1.02, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, P = .009) and baseline PHQ-2 score (IRR = 1.40, 95% CI, 1.06–1.84, P = .017). Of symptoms experienced by patients at enrollment, only the severities of decreased sense of smell (IRR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.05–1.70, P = .017) and decreased sense of taste (IRR = 1.41, 95% CI, 1.09–1.82, P = .008) were associated with PHQ-2 score. No other symptom severity at enrollment was associated with PHQ-2 score. Multivariable analysis confirmed that PHQ-2 score was associated with age (IRR = 1.02, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, P = .006), baseline PHQ-2 score (IRR = 1.39, 95% CI, 1.09–1.76, P = .007) and severity of decreased sense of smell (IRR = 1.40, 95% CI, 1.10–1.78, P = .006). The relationship between PHQ-2 score, decreased sense of smell, age, and baseline PHQ-2 score is shown in Figure 2. Because the severities of decreased sense of smell and decreased sense of taste were highly correlated (ρ = 0.84, P < .001) and inclusion of both decreased sense of smell and decreased sense of taste in a multivariable regression model lead to inflated VIFs for these variables (>8 in comparison to <2 for all other predictor variables), the multivariable regression model to check for association with PHQ-2 included decreased sense of smell—which is believed to be the primary driver of taste disturbance23—but not decreased sense of taste. However, inclusion of decreased sense of taste into the multivariable regression model instead of decreased sense of smell led to qualitatively similar results. Importantly, the reported severity of no symptom at its worst during the COVID-19 disease course was associated with PHQ-2 score at enrollment (P > .05 in all cases) and the severity of no symptom at baseline was associated with PHQ-2 score at baseline (P > .05 in all cases).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .009 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .006 |

| Gender | 1.31 (0.72–2.39) | .377 | 0.85 (0.48–1.51) | .578 |

| Smoking | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | .576 | 0.86 (0.65–1.13) | .276 |

| Baseline PHQ-2 score | 1.40 (1.06–1.84) | .017 | 1.39 (1.09–1.76) | .007 |

| COVID-19 symptom severities at enrollment | ||||

| Decreased sense of smell | 1.34 (1.05–1.70) | .017 | 1.40 (1.10–1.78) | .006 |

| Decreased sense of taste* | 1.41 (1.09–1.82) | .008 | 1.48 (1.14–1.90) | .003 |

| Nasal obstruction | 1.08 (0.72–1.62) | .714 | 0.92 (0.61–1.38) | .689 |

| Rhinorrhea/nasal mucus production | 1.74 (0.96–3.15) | .070 | 1.29 (0.75–2.23) | .360 |

| Fever | 1.35 (0.91–1.99) | .135 | 1.26 (0.88–1.79) | .202 |

| Cough | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | .441 | 1.08 (0.74–1.57) | .681 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.11 (0.74–1.67) | .611 | 0.92 (0.62–1.39) | .705 |

- CI = confidence interval; IRR = incident rate ratio.

- * Multivariable results from replacing decreased sense of smell in multivariable model.

Association of Anxiety with COVID-19 Symptom Burden

We next checked for association between GAD-2 scores and patient characteristics, including symptom severities at enrollment (Table III). On univariate association, GAD-2 score was positively associated with age (IRR = 1.03, 95% CI, 1.01–1.04, P = .003), baseline GAD-2 score (IRR = 1.52, 95% CI, 1.18–1.97, P = .001) as well as the severities of decreased sense of smell (IRR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.03–1.63, P = .027), decreased sense of taste (IRR = 1.33, 95% CI, 1.04–1.70, P = .022), and rhinorrhea (IRR = 1.85, 95% CI, 1.08–3.17, P = .025). No other symptom severity at enrollment was associated with GAD-2 score. Multivariable analysis confirmed that GAD-2 score was associated with age (IRR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.01–1.04, P = .025), baseline GAD-2 score (IRR = 1.55, 95% CI, 1.24 = 1.94, P < .001), and severity of decreased sense of smell (IRR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.02–1.62, P = .035). The relationship between GAD-2 score, decreased sense of smell, age and baseline GAD-2 score is also shown in Figure 2. Again due to collinearity, the multivariable regression model to check for association with GAD-2 included decreased sense of smell but not decreased sense of taste as a predictor, although inclusion of decreased sense of taste into the multivariable regression model instead of decreased sense of smell led to qualitatively similar results. Importantly, the reported severity of no symptom at its worst during the COVID-19 disease course was associated with GAD-2 score at enrollment (P > .05 in all cases) and the severity of no symptom at baseline was associated with GAD-2 score at baseline (P > .05 in all cases).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | .003 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .025 |

| Gender | 1.56 (0.87–2.79) | .132 | 0.93 (0.53–1.65) | .811 |

| Smoking | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | .49 | 0.88 (0.67–1.15) | .356 |

| Baseline GAD-2 score | 1.52 (1.18–1.97) | .001 | 1.55 (1.24–1.94) | <.001 |

| COVID-19 symptom severities at enrollment | ||||

| Decreased sense of smell | 1.29 (1.03–1.63) | .027 | 1.29 (1.02–1.62) | .035 |

| Decreased sense of taste* | 1.33 (1.04–1.70) | .022 | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | .042 |

| Nasal obstruction | 1.13 (0.77–1.66) | .545 | 1.09 (0.74–1.61) | .673 |

| Rhinorrhea/nasal mucus production | 1.85 (1.08–3.17) | .025 | 1.22 (0.74–2.02) | .431 |

| Fever | 1.31 (0.90–1.89) | .154 | 1.24 (0.90–1.70) | .193 |

| Cough | 1.07 (0.76–1.50) | .707 | 0.87 (0.60–1.26) | .454 |

| Shortness of breath | 1.31 (0.90–1.89) | .155 | 1.32 (0.91–1.91) | .146 |

- CI = confidence interval; IRR = incident rate ratio.

- * Multivariable results from replacing decreased sense of smell in multivariable model.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 remains a global threat to public health, having affected millions of individuals and killed hundreds of thousands.3, 24, 25 Moreover, it will likely remain as a global threat until a vaccine is created. In the meantime, detection of infected individuals is critical to stopping spread of the disease and thus it remains of great importance to continue to learn and understand the many disease manifestations of COVID-19. Although COVID-19 was first described in relation to symptoms of fever, cough, and shortness of breath, it has become apparent that the manifestations of COVID-19 are highly variable and may impact many different organ systems.4, 5, 26, 27 One element of COVID-19, which may have lasting consequences, is emotional disturbance of affected patients.18 Diseases that are inherently dangerous or have severe consequences are great sources of depression and anxiety for affected patients and post-convalescent, post-traumatic stress.7-9 The disturbances in emotional health due to COVID-19 have yet to be fully characterized and will require much study now and in the future. As one approach, in this study we investigated the burden of depressed mood and anxiety in a cohort of COVID-19 patients in relation to their COVID-19 symptomatology. We found that depressed mood and anxiety were positively associated with COVID-19 symptoms of decreased sense of smell and taste. In contrast and surprisingly, depressed mood and anxiety were not associated with symptoms of COVID-19 such as fever, cough, or shortness of breath, which may be harbingers of more dire COVID-19 outcomes. Additionally, we found that older age and baseline (pre-COVID-19) levels of depressed mood and anxiety were positively associated with greater depressed mood and anxiety during COVID-19.

Olfactory dysfunction (OD), ie, decreased sense of smell, has recently been identified as a symptom that is highly prevalent in COVID-19, occurring in up to 80% to 90% of COVID-19 patients.6, 28, 29 OD in the setting of COVID-19 is also highly correlated with decreased sense of taste.6, 28, 29 Participants from this cohort have been previously studied with respect to the prevalence, timing, and severity of sinonasal symptoms as well as classic COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, and shortness of breath.19 The prevalence of OD was comparable to past studies, and we also found that OD was quite severe when it occurred.19 The severity of OD occurring in these participants was associated with younger age and female gender, and also tended to correlate with more severe symptoms of COVID-19, such as shortness of breath.19

Chemosensory dysfunction, outside of the context of COVID-19, has been previously shown to be associated with decreased quality of life as well as anxiety and depression.30, 31 It is also described that depression may lead to OD.32 However, in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic and wide public recognition of the potential lethality of SARS-CoV-2 infection, we report here that the severities of classic and worrisome symptoms of COVID-19—such as fever, cough or SOB—were not associated with emotional disturbance while chemosensory dysfunction was. The COVID-19-specific nature of this relationship was highlighted by the finding that reported severities of baseline OD or taste loss were not associated with baseline depressed mood or anxiety. Certainly it is possible that OD in COVID-19 may be due to inflammatory obstruction of the olfactory cleft or infection of non-neuronal supporting cells of the olfactory epithelium, rather than infection of olfactory neurons, and any such mechanism for OD may cause emotional disturbance. However, one intriguing hypothesis worthy of consideration, as the global health community races to understand COVID-19 pathophysiology, is whether chemosensory dysfunction and emotional disturbance may be mediated by direct viral pathogenesis. Previous animal studies of the closely related SARS-CoV-1 demonstrated neurotropism of the virus, with infection of the olfactory tract found to be a route for spread into the central nervous system (CNS).33, 34 More recently CNS manifestations of COVID-19 have been described as agitation, confusion, seizures, and diffuse corticospinal tract signs,35, 36 and the neuroinvasive potential of COVID-19 has also been hypothesized to be associated with respiratory failure.37 The direct effect of COVID-19 on the CNS has been confirmed with the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid38 and a transcribiform mechanism for CNS invasion (eg, through olfactory neurons) has been proposed.39 Just as the extracranial manifestations of COVID-19 are highly varied in severity and the immediate danger posed to patients, so too may be the intracranial, CNS manifestations. Given the very COVID-19-specific and isolated association of depressed mood and anxiety with decreased senses of smell and taste, we therefore raise the possibility of emotional disturbance as a possible CNS manifestation of COVID-19.

Our study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations, the most conspicuous of which is that we cannot show any direct causal link between chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 and emotional disturbance. Animal studies and post-mortem studies of infected individuals will yield much direct evidence to support the CNS manifestations of COVID-19. However, clinical insights and observations may generate hypotheses for disease manifestations to be investigated in future studies and it is to that end that we hypothesize etiologies for the associations described herein. Our study also relies on patient recall of COVID-19 and emotional symptoms from before COVID-19 to their current state, which introduces the possibility of recall bias.40, 41 However, as the mean time from onset of COVID-19 for these participants was 12 days, it is unlikely that participants would be experiencing significant recollection error, especially as it relates to disease-specific manifestations.42, 43 Although recall bias in the form of reconstruction error is a possibility, it is unclear why that bias would be towards associating emotional disturbance with chemosensory disturbances, rather than more immediately concerning symptoms such as fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Additionally, the PHQ-2 and GAD-2 assess symptoms of depressed mood and anxiety over the prior 2-week period but some participants in our study had been experiencing COVID-19 symptoms for less than 2 weeks so it is possible that some COVID-19-associated PHQ-2 and GAD-2 scores included a reflection of the pre-COVID-19 state. Finally, our study relies on patient-reported subjective assessment of OD but did not use objective measures of OD. Subjective measures of OD can underestimate objective OD in COVID-19,44 and emotional disturbance could further alter this relationship.

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 is associated with significantly increased burden of depressed mood and anxiety. Of all symptoms experienced by COVID-19 patients, decreased sense of smell and the associated decreased sense of taste are most dominantly associated with depressed mood and anxiety. Intriguing explanations, ranging from highlighting the great importance of chemosensory disturbance in emotional wellbeing (overwhelming even the impact of potentially lethal symptom manifestations of COVID-19) to demonstrating emotional disturbance as a possible CNS manifestation of COVID-19—must be considered and further studied.