Is hearing preserved following radiotherapy for vestibular schwannoma?

Editor's Note: This Manuscript was accepted for publication June 12, 2018.

a.r.c. and a.a.h. contributed equally in the production of this manuscript.

None of the authors received remuneration, reimbursement, or honorarium in the production of this manuscript. s.g. receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIH/NIDCD) for work unrelated to this project and is on the scientific advisory boards for Applied Genetic Technologies Corporation and Roche. He has also received an honorarium from Decibel Therapeutics for consulting. a.a.h. was supported by the University of Colorado Otolaryngology T32 training grant from the NIH/NIDCD.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

BACKGROUND

A common question by patients with newly diagnosed vestibular schwannomas (VS) is, “Which treatment will best preserve my hearing?” Currently, management of this benign tumor arising from the eighth cranial nerve sheath includes three broad options: observation with serial imaging, microsurgery, and radiotherapy. There are no high-quality, prospective controlled trials comparing outcomes among these three treatment modalities. Therefore, treatment recommendations are largely based on data from single-institution case series. As outcomes of tumor control and facial nerve preservation have improved with modern surgical and radiotherapy techniques, the possibility of hearing preservation (HP) often plays a significant role for patients and physicians making treatment decisions.

The heterogeneity of data poses a major challenge to providing accurate estimates of hearing preservation rates with radiotherapy for VS. Indications for treatment and inclusion criteria vary widely by institution. Radiation may be delivered in a single dose or as many as 30. The radiation source may be cobalt (e.g., GammaKnife surgery [GKS]) or a linear accelerator (e.g., CyberKnife). The methods for reproducing localization differ between techniques as well. Moreover, hearing outcomes are not standardized. For example, some publications simply report the patient's subjective ability to use the telephone at the first post-treatment visit, whereas other studies utilize audiograms to provide an objective measure of hearing in the treated ear. Traditionally, serviceable hearing has been defined as pure-tone audiometry (PTA) < 50 db with speech discrimination scores (SDS) > 50%, corresponding to American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) class A or B, or Garner-Robertson (GR) grade 1 or 2. These differences result in widely varied rates of hearing preservation (between 10% and 90%) after radiotherapy for VS.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Modern techniques for radiotherapy-based treatment of VS have improved significantly since the first publication of this technology for VS treatment in the 1970s in Sweden and the early 1990s in the United States. A high-quality systematic review of hearing preservation after GKS radiosurgery was published in 2010 by Yang.1 They examined 45 publications with 4,234 patients and calculated an overall hearing preservation rate, as defined by maintenance of AAO-HNS A/B or GR grade 1/2, of 51%. Doses ≤ 13 Gy were significantly associated with better hearing preservation. Tumor volume and patient age did not correlate with hearing preservation rates. The average follow-up time was 44.4 ± 32 months, with a median of 35 months. Importantly, this study only evaluated GKS and crude hearing preservation rates without examining time-based hearing preservations rates. Since this systematic review was published, there have been several new case series reporting long-term hearing preservation rates in patients treated with modern radiotherapy techniques.

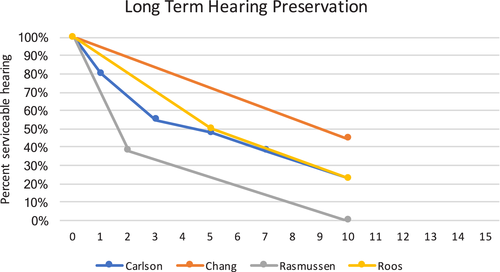

Carlson and colleagues2 retrospectively examined 44 patients undergoing GKS with a median audiometric follow-up time of 9.3 years. Audiometry was evaluated using the AAO-HNS scale. The marginal dose was 12 Gy in 41 patients and 13 Gy in three patients. The authors performed 10-year Kaplan-Meier actuarial estimates of the percentage of patients maintaining class A/B hearing, which showed a progressive decline: 80%, 55%, 48%, 38%, and 23% at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10 years following GKS, respectively. Anticipating some age-related hearing loss over a 10-year period, the authors attempted to account for this by including an interaural correction and showed, in the contralateral ear, an 8.5-dB increase in PTA and a 1.8% drop in SDS over the long follow-up course. Even after accounting for this adjustment, the treated ear demonstrated continued hearing loss throughout the course of long-term follow-up. On multivariate analysis, they found pretreatment PTA and tumor size were associated with time to loss of class A/B hearing.

The University of Pittsburgh published their low-dose GKS outcomes on 216 patients treated between 1992 and 2000.3 Marginal GKS doses were 12 Gy in 21 patients, 12.5 Gy in 11 patients, and 13 Gy in 184 patients. The median follow-up was 68 months. Before radiosurgery, 106 patients had GR class 1 or GR class 2 hearing, with a 10-year actuarial hearing preservation rate of 44.5% ± 10.5%. Fifty-seven percent of these patients preserved GR 1/2 hearing at last follow-up. The authors also noted a continued decline in hearing preservation rates as time to follow-up increased, particularly beyond 6 years. Multivariate analyses revealed treatment volume was significantly correlated with a drop in hearing classification.

Rasmussen et al.4 evaluated 42 patients receiving 54 Gy of fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) in 27 to 30 fractions, with a median follow-up of 5 years. All patients were prospectively followed with magnetic resonance imaging and audiograms 1, 2, 3.5, 5, 7, and 10 years after FSRT. Twenty-one of 42 patients had GR class 1 hearing before FSRT, of whom, eight (38%) retained GR 1/2 hearing 2 years posttreatment. Seven of these patients were followed for 10 years; none retained GR 1/2 hearing 10 years after FSRT.

Roos et al.5 reviewed their experience with single-dose, linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery. Although they lacked speech discrimination scoring, they reported HP rates relative to interaural PTA differences in 50 patients with pretreatment hearing <50 dB PTA. Patients were followed for a median of 65 months, and similarly showed a significant relative decline in the ipsilateral serviceable hearing preservation rate. The Kaplan-Meier actuarial estimates of HP were 50% at 5 years and 23% at 10 years. Initial PTA was a significant factor associated with hearing preservation.

Although there is heterogeneity of the methodologies, there is reliable evidence demonstrating that with long-term audiometric follow-up, there is a continued decline in hearing preservation rate, with remarkable agreement of HP rates in the long-term case series (Fig. 1). Initial pretreatment hearing class, tumor size, and cochlear dose appear to affect the hearing preservation rates. There is a lack of high-level evidence to support differences in hearing preservation based on radiotherapy equipment or fractionation technique.

Actuarial hearing preservation for four selected long-term case series. 1/2 = Garner-Robertson grade 1 or 2; A/B = American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery class A or B. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.laryngoscope.com.]

BEST PRACTICE

The level of evidence of reviewed articles is low. Given that the field involves rapidly developing technology, this is not surprising. Moreover, synthesis of data from case series is vitally important, as controlled studies comparing radiotherapy against microsurgery or conservative management would logistically be very challenging. Evidence from modern, highly conformal, low-dose radiation techniques demonstrate that long-term hearing preservation rates are poor; an approximately 80% hearing preservation rate at 2 years posttreatment falls to approximately 23% at 10 years. Although radiation therapy provides patients with satisfactory short-term hearing preservation, this treatment modality does not reliably preserve hearing in the long term. It is important when assessing publications in this field to thoroughly scrutinize the methodology, systems of hearing classification, and time to follow-up to provide patients with the most accurate estimations of hearing preservation.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Our review included one systematic review of case series and four individual case series (level 4).